Pooja K. Agarwal's Blog, page 4

May 16, 2023

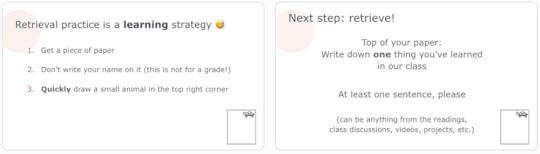

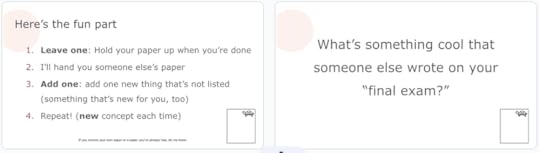

Classroom activity for retrieval practice: Leave One, Add One

As we approach the end of the semester and the end of the school year, I want to share one of my favorite activities for retrieval practice: I call it Leave One, Add One. Click here to view and download my Google Slides for this activity.

Time: Approximately 30 minutes total (15 minutes for writing, 15 minutes for discussion)

Grade level: 6th grade through graduate school. You can use this activity during professional development, too.

Content area: All of them! STEM, language arts, history, etc.

Materials: Blank paper and pencils/pens

Leave One, Add One

Photo by Mikhail Nilov (Pexels)

Here’s are the steps for Leave One, Add One:

Hand out one sheet of blank paper to each student.

Have students draw an animal in the top right corner of the paper (without writing their name down; this is anonymous). Keep it quick; give students only 30 seconds to draw.

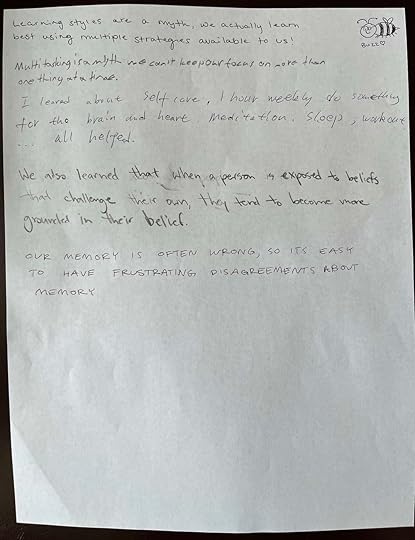

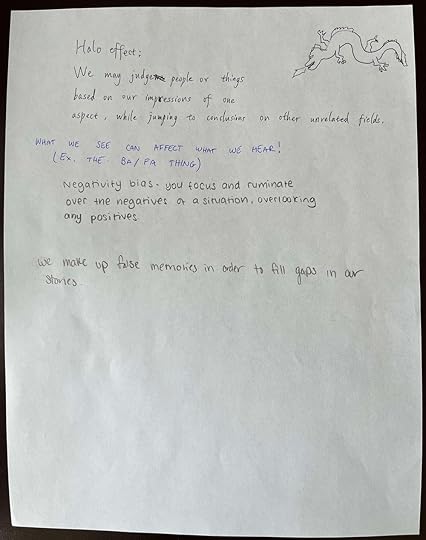

Ask students to silently retrieve and write down one idea or concept they’ve learned in class. It can be their favorite thing or the first thing that comes to mind, related to any course material, etc. This should be at least one full sentence.

Collect all students’ papers and explain the process for Leave One, Add One: Students have now “left one” on their piece of paper. Each time they receive someone else’s sheet of paper, they should “add one.” In other words, students should retrieve and write down one new thing they learned in class. This should be something new that isn’t already on the piece of paper, and also something new that the student didn’t write down on a previous piece of paper.

Shuffle students’ papers and hand them back in a random order. When students are done adding one thing, they should hold up their paper for you to collect and re-distribute. While students are writing, the activity is silent and self-paced.

Continue collecting and handing out of papers for a few rounds, until students start receiving papers they have had before (for a class of 20 students, I recommend 5–6 rounds). This self-paced process will get a bit zany as you run around collecting and handing out papers, but it’s a lot of fun, too.

Once you’re done with the rounds, collect all papers. Use the animal drawings to hand back the papers to the original student (you can hold the paper up and call out the name of the animal).

Class discussion: Students should share one thing cool that someone else wrote on their paper. If you’d like the discussion to continue, have students share two things from their paper. You’re done!

Important: Don’t grade the papers! Retrieval practice is a learning strategy, not an assessment strategy. Students can keep their paper as a reminder of what they’ve learned, they can recycle them, or you can collect them just to look at them – but make sure it’s clear that it’s not for a grade. Use Leave One, Add One for spaced retrieval practice and boost students’ long-term learning.

Download the Google Slides

Download the Google Slides More context and tips:

Before I start, I tell my students that this we have a pop final exam (I’m just kidding! Click here for my Google Slides I use in class). Some students groan, while other students catch on quickly that I’m joking.

Some of my students automatically write their name on the piece of paper as soon as they receive it. Why? Now that my college students have had an entire semester with me and they’ve learned about retrieval practice, I make light of the situation: I explain that, in our educational systems, we are so used to grading everything that it’s become an ingrained habit for students to write their name down. If a student wrote their name down, give them a new blank sheet of paper so that the activity is anonymous.

Reminder: For retrieval practice, silence is golden. Encourage students to write silently until writing ends and class discussion begins.

Scaffolding: During class discussion, each student is reading one thing that’s on the paper in front of them, so they’re not put on the spot. This can be particularly helpful for English language learners and students who need more time to think.

Examples of Leave One, Add One from Dr. Agarwal’s class

Quick Teaching Tip for Class Discussion

Quick Teaching Tip for Class Discussion

During class discussion, when a student is speaking, walk to the other side of the classroom. The student will naturally start talking more loudly and all students in the classroom will feel included in the conversation.

Credit: Leave One, Add One is my adaptation of an activity called “ink shedding,” attributed to James Lang, author of Small Teaching and On Course. The quick teaching tip to improve class discussion is also from James Lang. On Course is one of my favorite teaching books of all time. Make sure to add his books to your summer reading list.

How to Bulk Order Powerful Teaching

Many of you have asked how to bulk order Powerful Teaching using ESSER funds and/or for summer book clubs (thank you!).

For bulk orders (hardback and e-book), email Victoria Finley, Account Manager at Wiley Publishing, at vfinley@wiley.com. Discounts range from 25% – 40% off, depending on the size of your order.

For exclusive resources for book clubs, email my co-author Patrice Bain at patrice@patricebain.com.

Join our Powerful Teaching Facebook group and download our free lesson templates

Powerful Teaching is available in hardback, e-book, audiobook, and also in Spanish

Help us: Leave a rating or review on Amazon for Powerful Teaching

I acknowledge that promoting book sales and requesting Amazon reviews is awkward. The reason for my request is that providing Powerful Teaching to teachers supports their long-term learning and classroom implementation with a tangible resource. I have found that this approach is much more effective than "one and done" professional development. I receive less than $1 per book sold, so it’s not about the money. It’s genuinely about sharing the science of learning around the world. Thank you for your support!

Pooja K. Agarwal, Ph.D. (she/her)

Founder, RetrievalPractice.org

Cognitive Scientist, Teacher, & Author

@RetrieveLearn

April 28, 2023

What should you do when your students can't retrieve anything?

When someone asks me what I did last weekend, my mind goes blank. I struggle to mentally time travel to the past, but eventually, I can come up with something.

Do your students’ minds go blank during an in-class retrieval practice activity? You’ve probably had at least one student who was frustrated and said, “But I can’t retrieve anything!” Here are 4 steps you can take to help your students retrieve something.

P.S. My newsletter subscribers received a free chapter of Powerful Teaching. Click here to subscribe.

How to scaffold retrieval practice

Retrieval practice is a mental struggle (a “desirable difficulty” for long-term learning), which means it can also be frustrating. Contrary to what your students might feel, there is always something they can retrieve. Here are 4 steps you can take to scaffold an in-class retrieval practice activity:

Remind students that we all need time to think. A reminder for you and your students: the mental struggle during retrieval practice is good for learning, whereas easy learning is easy forgetting. Telling students to “try harder” isn’t going to help. Validate that retrieval is hard, remind them that taking a “mental moment” will boost their long-term learning, and don’t skip the think step during think-pair-share.

Encourage students to sit with the struggle a little longer. We have the natural temptation to jump in and help students as soon as they struggle, but this is a disservice to them and their learning. Instead, give students a clear instruction to try for another minute, and use a clock or timer to make sure you give them the full minute. (I’m a fan of radial timers.)

Emphasize that silence is golden. It’ll feel awkward for you and your students to sit in complete silence during step #2. We have an ingrained belief that students must be talking in order to be engaged. Quite the contrary! We think best and engage in learning when there aren’t distractions (some of my students close their eyes to help them think). Plus, once your students experience a minute of silent retrieval practice, you’ll be surprised by how quickly they get used to it and then ask for more silent time to retrieve.

Give your students a retrieval cue. A retrieval cue isn’t necessarily a hint, but a reminder that might lead to that “ah ha!” feeling when something comes to mind. For example, I asked my students to retrieve what they learned when we discussed implicit bias a few weeks ago. If they draw a blank, a retrieval cue I provide is “reliability and validity.” That “cues” their memory without giving them a direct hint (we discussed the implicit association test). In the same way, if you ask students to retrieve what they learned in class last week and they can’t remember, give them a one-word or two-word cue. Avoid the temptation to give students the answer.

What should you do when some students retrieve more quickly than other students? Ask them to retrieve more! If you had your students retrieve two things, ask the students who finished first to add one or more new things to their list.

Summer reading: Powerful Teaching and Make it Stick

Are you reading Powerful Teaching and Make it Stick this summer? We’ve got resources to support your learning!

Download free templates from Powerful Teaching, including “thinking signs” from Patrice’s classroom (like the one above) and our neuromyths quiz

Download free discussion questions for Make it Stick, including sketchnotes and recommended research articles

Join our Powerful Teaching Facebook group and exchange ideas with nearly 3,000 teachers around the world

Explore my list of 15+ recommended books on the science of learning

Check out my list of professional development resources to create your own program

Get a bulk discount on Powerful Teaching for your school

Are you hosting a Powerful Teaching book club this summer? Contact my co-author Patrice Bain (patrice@patricebain.com) for more resources, including a welcome video, personalized autographed book plates, and an exclusive PDF with even more discussion questions.

March 31, 2023

Celebrate women in STEM by citing women in STEM

Did you know that two of the lead inventors of the COVID vaccine in the United States are women? Did you also know that there is systemic gender bias in science, where women are consistently cited less frequently than men?

Join me in celebrating and amplifying women in STEM by downloading and sharing our new list of recommended citations on the science of learning. By using this curated bibliography, you can:

Increase citation rates of diverse scholars in cognitive science

Update your citations with the newest research on learning

Visibly demonstrate your commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in STEM

Raise awareness of implicit bias and microaggressions in science and beyond

Of all the ways to increase diversity in STEM, why focus on citations? Because it’s a simple and quick way you can make a difference. We created a bibliography to make it even easier for you.

Why STEM citations matter

Photo by Women in Tech Chat

Citations aren’t just a boost to one’s reputation or ego. In STEM fields, citation rates can influence career outcomes, including hiring and promotion decisions, publication authorship, salaries, and grant funding. There is consistent evidence that women are cited less than men and also that the background of scientists can impact research: the questions asked, the participants recruited, and the conclusions drawn.

Update your citations: I am thrilled that educators are sharing resources and teaching ideas based on the science of learning and I’m glad when I see reference lists and citations. But I’ve noticed a consistent pattern: many citations in blogs, infographics, websites, and presentations are at least 20 years old. First, we’ve learned a lot about how learning works in the past two decades. Second, I worry that if we rely on outdated citations to indicate authority, not evidence, retrieval practice will become just another fad in education.

Hold yourself accountable: If you use this bibliography to diversify your citations, consider adding a statement of commitment to your blog, infographic, website, presentation, edtech materials, or news articles. For example: “We demonstrate our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the science of learning by citing women, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ cognitive scientists.” This isn’t required to use the bibliography; it’s a statement to publicly acknowledge and hold your organization accountable for amplifying diverse voices in STEM by the citations you choose to use.

More resources and downloads

TL;DR… Here are three new resources for you:

A list of recommended citations on the science of learning

A YouTube playlist featuring women in cognitive science

My Google Slides when I teach my students about implicit bias and microaggressions

In the bibliography, I included 10 recommended citations on retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, study strategies, and early childhood learning. Does the list capture all of the literature on the science of learning? No, of course not. I recognize that I have cherry picked only 10 publications, which includes a selection of newer research by diverse scientists, with direct applications to education and/or research conducted in real classrooms.

If you’d like a more comprehensive look at research, my colleagues and I published a literature review of classroom research on retrieval practice, including 50 experiments spanning elementary school through medical school. We found that retrieval practice consistently benefits student learning, with the majority of the experiments yielding medium to large effect sizes. You can also download our open access database of the 50 experiments (a Google spreadsheet).

We provide even more recommended research (40 publications, to be exact) in our Retrieval Practice expert list of underrepresented cognitive scientists. You can sort by areas of expertise, and each expert profile includes new links to news articles and YouTube videos featuring their research. Across the list of 40 experts on retrieval practice research, we have scholars located in 5 countries around the world and we speak a total of 11 different languages.

Please use the Retrieval Practice expert list as a resource when inviting speakers for professional development opportunities and collaboration initiatives to further demonstrate your commitment to DEI efforts in STEM.

What you can do in your classroom

Photos by The New York Times

Two of the lead inventors of the COVID vaccine in the United States are women, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett and Dr. Katalin Kariko. As we move onto the next stages of the pandemic, we need make sure that their scientific research and advancements in medicine are acknowledged, cited, and celebrated.

Here are my Google Slides from my cognitive psychology course when I teach my college students about implicit bias and microaggressions. The slides include 3 sets of 45-minute blocks:

Information and videos about implicit bias, the Draw a Scientist program, and the inventors of the COVID vaccine

Research about how scientists measure implicit bias

Videos and discussion questions about microaggressions

You are welcome to use my slides in your classes. Note that the content in my slides may be most appropriate for ages 18+ and one of the videos contains a racial slur. You could also use these slides in your professional development to discuss implicit bias. Spoiler alert: psychology research demonstrates that there may be little to no effect of diversity training on long-term outcomes and behaviors, but I think conversations are a good first step toward raising awareness about implicit bias. Here is a Time Magazine article about the inventors of the COVID vaccine.

If you and your students want to dive in even more, here’s additional research on bias in STEM fields: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Frontiers in Psychology, Perspectives on Psychological Science, Current Directions in Psychological Science, and The Pew Research Center. I also recommend reading about an the #CiteBlackWomen initiative in physics and astronomy, this article written by a trans scientist about their experience in STEM, and a commentary entitled The Future of Women in Psychological Science by 59 leaders in psychology (here’s a podcast about the commentary).

Personal reflection

On a personal note, raising awareness of bias and initiating conversations about bias is hard. As a scientist who identifies as a woman of color, I continue to receive microaggressions, experience casual sexism and racism, and face overt sexist and racist behaviors by others, personally and professionally.

I also receive encouragement and support from my colleagues (particularly those on the expert list), educators around the world, and my college students. When I recently asked my students to draw a scientist, one of my students drew me (photo above).

In an article by trans neuroscientist Atom J. Lesiak, their advice for scientists and allies really resonated with me: “Be brave in your allyship and advocacy. It feels scary to speak up against injustice and harassment, but it is worth the risk. It can be intimidating to have to educate a senior faculty member on how they can improve their behavior, when you know they have the power to impact your career.”

Increasing citation rates for women, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ scientists is small, but it’s a start. I hope you’ll join me in this allyship and advocacy to amplify diverse voices in the science of learning.

February 13, 2023

How do you know if retrieval practice improves learning in your classroom? Conduct research!

I love receiving emails from educators who are interested in conducting research in their classroom. We know that retrieval practice improves learning. But does it improve learning in your classroom? It’s important to find out!

Here’s how to get involved and start conducting your own research:

Join our subscriber-only Zoom party this Friday, Feb. 17 from 5:00pm - 6:30pm EST. We’ll be geeking out about how to conduct research. (Not an email subscriber? Sign up!)

Email us at ask@retrievalpractice.org and simply let us know if you’re interested in conducting research in your classroom, school, or university. We’re exploring how we can provide support for both educators and scientists, and it’s really helpful to know who would like to get involved.

Find a cognitive scientist near you and email them to see if they’d like to conduct research in your school. Don’t be shy!

Check out this podcast interview about research with Jennifer Gonzalez (Cult of Pedagogy) and cognitive scientist Dr. Kripa Sundar, including resources and YouTube videos.

Read below for tips on how to decide what data to collect and what measurement techniques you can create.

Photo by Katerina Holmes

Question from Matthew, a history teacher in West Virginia: What would you consider to be solid baseline data to collect to look at retrieval practice and its effects? Test scores, anecdotal data, something else?

Recommendations from me: I commend you on your interest in collecting data to determine the benefits of retrieval practice in your own classroom and school. It can be difficult to measure learning – it’s quite a complex human process. You could compare previous grades to current grades and/or a mix of the measurements you listed.

You may also want to think about your ultimate goal: what does learning look like to you at the end of the day/month/school year? Once you have that in mind, you could then work backwards to construct a relevant survey or test to give students at the beginning and end of the school year.

From Matthew: You are correct that it is quite difficult to measure human learning, especially in a small mini-inquiry cycle within a school year. I like that you asked us to zoom out and look at what learning looks like at various points of the year. Our main focus could be on what we want to see improve; what it will look like if retrieval works/doesn't work; and how we can measure learning in a short cycle. I will take this back to my PLC and discuss!

Question from Stephanie, a school leader in New York: We often struggle to find the right levers for collecting student outcome data. Do you have advice to share regarding getting past implementation fidelity and getting to outcomes in student achievement? I’d love to know if our instruction around the science of learning is impacting teacher practice, and more importantly student outcomes.

Recommendations from me: Measuring the impact of evidence-based teaching strategies on student achievement can be a challenge, for sure. A few options:

A basic start is to provide a pre-survey and post-survey to measure students' thoughts on retrieval practice. Here is survey research we published about students’ study strategies and their thoughts on retrieval practice (1,500 K–12 students total).

You could provide "pop" ungraded pre- and post-exams, to measure student learning without consequences to students' grades. Here is a research article by Dr. Maya Khanna on retrieval practice with ungraded pop quizzes.

As we did in our classroom research with Powerful Teaching co-author and middle school teacher Patrice Bain, you could implement retrieval practice during some lessons–but not all lessons–and compare how students perform on an assessment for retrieved vs. non-retrieved content. Here is an article we wrote together about the research process.

Read about recent research on retrieval practice in classrooms around the world and download our spreadsheet to take a closer look at how the research was conducted and how learning was measured.

From Stephanie: This is amazing. Thank you so much for taking the time. Much appreciated!

In my 10+ years of classroom research, we used a specific type of research approach, called a “within-subjects design.” I just looked through my book, Powerful Teaching, and I'm surprised I didn't write about this!

Essentially, all students received retrieval practice. We did not have a “retrieval practice group” and a “control group” in the way people typically think of research.

Each week, students received retrieval practice on some lesson content (example: half the textbook chapter vocabulary was included on 5-min clicker quizzes each week) and no retrieval practice on the rest of the lesson content. Importantly, all lesson content was still taught by the teacher.

After a few weeks or months, we gave students a low- or no-stakes test to see how students did on questions about content that was included on the mini-quizzes vs. content that was not on the mini-quizzes. There was a lot of work behind the scenes to make this happen, especially to divvy up all the lesson content on different quizzes for different classes.

If you’d like to adapt a within-subjects design for research in your classroom, school, or university, start small: Cover your content and classes exactly like you do now, but simply add in a few non-graded questions on an assessment (ideally at the beginning and end of the course, semester, or school year). It might not be enough data to draw conclusions (yet), but it would be a great way to start a conversation with teachers and students about how to conduct research on retrieval practice.

January 25, 2023

How to create mnemonics and finally remember students’ names

Names are important for us and for our students. But they’re SO hard to remember.

I have 80+ students each semester. By the end of the first week, I have almost all of their names memorized. And I don’t even look at students’ faces on the LMS (they’re blurry or outdated anyways).

How do I do it? Here are my steps, tips, and class activities. It can take some practice (and retrieval practice!), but over time, your classroom will be a community where everybody knows your–and your students’–names. 🎵

Step 1: Create mnemonics

Photo by andrea piacquadio

Ask students to come up with an animal or food that starts with the same first letter as their first name (for example, Alex-Aardvark, Jess-Jalapeño, Taylor-Tiger)

Ask students to share their favorite show on TV/Netflix/Hulu, etc.

Ask students to share additional information about themselves (hobbies, pets, vacations; my personal favorite is to ask about their least favorite ice cream flavor)

Create mnemonics: a “concrete connection” between the student’s name and one of the items (food, animal, TV show, ice cream)

Here are some memorable mnemonics my students and I created this week: Ava-Avocado, Nick-Narwhal, and Daniel-Dragon. On Flip (a tech tool), a student named Ella mentioned that she likes the show Schitt’s Creek, which I also enjoy, so we already have something to talk about. On my Google Form, a student named Jackie mentioned that she went to high school in the same town in Illinois where I was born. Casey and I both hate mint chocolate chip ice cream. Not only do the mnemonics help me remember names; they help me build connections with students right away.

Step 2: Get students involvedHave students go around the room and share their name, animal/food, and their least favorite ice cream flavor. In this way, students are helping other students create mnemonics.

During class discussion at the start of the semester, aim to use a students’s name-noun pair as much as possible (“thanks for sharing, Ava-Avocado”).

If you can’t remember a student’s name, ask for help from other students. More specifically, ask for a hint with the student’s animal or food, not their name. Students really enjoy this form of retrieval practice!

Have a conversation about learning, forgetting, and retrieval practice. You’ll make mistakes and they’ll make mistakes – but retrieving, practicing, and making mistakes is how we learn. Consider telling your students that a hint can also be called a “retrieval cue.” Normalize forgetting and model how retrieval practice is good for learning.

Once class is done (or a few hours later), do a brain dump and write down all the student names you can remember, with or without their mnemonics.

The following week, ask students to write down all the names they can remember from class and have a discussion: How did they do? Did they remember more than they expected? What was easiest to remember, names, animals, foods, or something else? Why?

A week or two later, play Noun-Name Tag (way more fun than the ever-fashionable name tags). In popcorn style, have one student say the noun and name of another student, and continue to play “tag” until everyone has been called on. (More about this strategy in my book, Powerful Teaching, pages 223–225. Noun-Name Tag works well for class sizes of 20 students or fewer.)

More activities in Powerful Teaching What it looks like for me and my classroomBefore the first day of the semester, my students introduce themselves on Flip (a video selfie platform; here is an example on Flip, but you’ll need to login via Microsoft, Google, or Apple) and they complete a Google Form (here’s an example of my intro form; feel free to fill it out and introduce yourself!).

I write my mnemonics on a printed roster the night before class. The next morning, I quickly try to retrieve any name-mnemonics I can, and then I review my notes before class (don’t judge; cramming works in the short term). For a class of 25 students, I’d estimate that I have solid mnemonics for 5 students, perhaps good-ish mnemonics for 10 students, and probably no mnemonics for 10 students. For me personally, I choose to focus on quality over quantity.

When a student walks in my classroom and tells me their name, the name is my retrieval cue, not their face. When Ella introduced herself, you better believe I was excited to ask who her favorite character is on Schitt’s Creek.

View my Google Form 8 additional tips for remembering namesMake the mnemonic as concrete as possible. Erica-Energetic is abstract. Erica-Elephant is more specific and easier to visualize. (This is why occupations are easier to remember than names.)

Make the mnemonic as unique as possible. Alexandra-Apple is okay, but Alexandra-Aardvark is better. Challenge students to choose unique animals and foods, too.

When you’re first starting, focus on using names as retrieval cues, not faces (“Nice to meet you, Alexandra. I remember that you chose aardvark.”).

Later in class, use mnemonics as retrieval cues (“hmmm, your animal was aardvark… lemme think and retrieve… I got it, your name is Alexandra!”).

Try to strike up a conversation with a student about their favorite TV show or least favorite ice cream flavor. The more you build a connection with a student (even if it’s small talk), the easier it’ll be to remember their name.

The process for creating mnemonics and the activities listed above work well for a range of ages: younger kids, as well as for high school, college, and graduate school students. Try this out at conferences, new jobs, or anywhere you need to remember names, too.

With large lecture or class sizes, the animal/food mnemonic can still be an engaging activity on the first day of class. It opens up a conversation about the science of learning and it’ll help students remember each other’s names (even if you can’t remember everyone’s names).

Try to incorporate a mix of retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, and feedback, as much as possible. Retrieve at the end of the day or end of the week; mentally visualize where students were sitting and retrieve their names, animals or food; challenge yourself to retrieve students from all of your classes in any order that comes to mind for interleaving; and don’t feel bad if you need to check your list of mnemonics. Just make sure to retrieve first!

More tips based on research (and bad tips from ChatGPT)Good tip from research: Here’s a recommended article by cognitive scientist Dr. Uma Tauber on how occupations are easier to remember than names, but people are overconfident in their memory predictions for names (published in 2010 in the journal Memory), so try to incorporate metacognition opportunities during retrieval practice.

Bad tips from ChatGPT: Out of curiosity, my friend Alexandra asked ChatGPT how to remember names. It suggested repeating the person’s name during the conversation (that will work for a few minutes, at most), imagining the name of the person written on their forehead (um, no), and writing down the name of the person (who would do that mid-conversation?).

Overall tip: stick with good old fashioned retrieval practice. Cheers!

Read Research on Remembering NamesJanuary 5, 2023

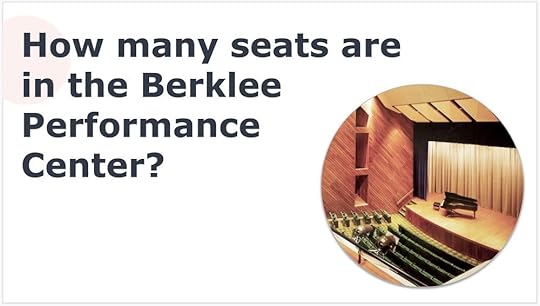

Use a trivia question to introduce students to retrieval practice

Retrieval practice improves long-term learning, it’s backed by a century of research, and you can implement it in one minute or less. But how do you get students on board? Here’s a simple strategy: start and end class with a trivia question.

What I do in my classroomOn the first day of class, I start by asking my college students a trivia question: “How many seats are in our auditorium?”

Quickly, I have students turn to a partner and guess, while I walk around the room and gather estimates. I announce the range to class, I pause before the punchline (oh, the suspense!), and then I reveal the answer (1,215 seats).

Now that I’ve got their attention, I introduce myself more fully, I preview the game plan for our first class, and I give an overview of the topics we’ll cover throughout the semester. Next, I tell my students that it’s important to me that they remember what they learn and I give three examples to demonstrate why:

I ask them, “You’re spending a lot of time, money, and energy on your college education, so don’t you want to remember beyond the semester and beyond the school year, for years to come?”

I point out that I remember very little from my college classes, which is such a waste (sorry, Mom).

I pose a simple scenario to my students: “You’ve all crammed for a test and done well, perhaps received an A. Cramming works! And then what happened?”

I pause and I enjoy the awkward silence, until a few brave students share that they forgot everything. Everyone begins to nod and we all agree: forgetting is frustrating.

I’ve got them hooked; there’s a common problem to solve. I explain my solution: in my class, we’ll be emphasizing long-term learning, and how we’re going to do it is using a research-based strategy called retrieval practice. I briefly elaborate with what retrieval practice is, what it looks like in my classroom (brain dumps, mini-quizzes, etc.), and how all assignments are low-stakes (learn more in my book). I don’t even present any research. I reassure my students: they’ll have less stress and remember more.

About one-third of the way into the first class, after discussing the nuts-and-bolts of the course, I ask the trivia question again. Approximately half of my class responds: “one thousand, two hundred fifteen.” It takes 10 seconds. We move on, and at the very end of the first class, I pose the trivia question, students respond in unison, and class is dismissed. Boom!

Approximately 6 weeks later (after we’ve discussed research and additional learning strategies), I ask the trivia question in passing. Then I end with it: my trivia question is literally on my last slide on my last class of the semester. My students love it, they remember it, and they know why.

Why a trivia question gets students on board with retrieval practice

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio (Pexels)

It’s unexpected, quick, and engaging

It’s a no-stakes demo where students are successful

It normalizes forgetting as a shared experience

It feels personalized when created carefully (see tips below)

It’s a simple example of how repeated and spaced retrieval practice increases learning

It sets a foundation for more conversations about learning and conversations about studying

Students are more receptive to tips to help them study smarter, not harder

When students remember the trivia fact, they’ll know why they remember it, too

Tips for creating a trivia questionIt took me awhile to figure out what works best for this activity. Here are a few tips:

Create a trivia question that is specific to your school, city, state, or country (the year something was created, the height of a notable statue on campus, the state animal, etc.).

The answer should be one word, a date, or a number. This will help your students respond in unison and build community.

Create a trivia question that very few students will know the answer to initially.

Create a trivia question that is appropriate and accessible for English Language Learners and international students who may be less familiar with pop culture.

The question and answer should be appropriate for pair discussion and/or a multiple-choice show of hands to give you added flexibility (particularly if you have large class sizes).

Don’t overdo it by asking the trivia question too often. Keep it unexpected and space it out (think of it like an expanding schedule over time).

Don’t launch into a long explanation about retrieval practice before or after you ask the question. Keep this quick and simple, and introduce research on retrieval practice later on.

What should you do after you start your first class with a trivia question? Ask students about what they learned during the summer/winter break or include a quick Retrieval Warm Up.

Use a trivia question with teachers, tooIt can be a challenge to get educators on board with retrieval practice. Try the trivia question demo at the beginning and end of professional development!

Whether you’re leading an in-service faculty workshop, a parent’s night, or a Zoom, start and end with a trivia question. Your audience will find it memorable and “meta” (retrieval practice about retrieval practice). And just like for students, if the answer is the only thing they remember from the professional development, they’ll remember why they remember it.

Watch the demo in action on YouTubeOctober 4, 2022

Here are 3 quick retrieval practice activities for your classroom

Craving a refresher on the science of learning and teaching tips for your classroom?

Here are three resources for you:

Reach out to our featured scientists for a workshop or interview

Read our retrieval practice activities that take one minute or less

Check out the list below for my upcoming in-person and virtual events

Quick retrieval for long-term learning

Photo credit: Freepik

Retrieval practice doesn't take much classroom time – we promise. Here are our quick strategies to implement this powerful research-based strategy and improve long-term learning in your classroom:

Warm Ups: Ice breakers are okay, but Retrieval Warm Ups are better. Students retrieve their experiences with fun prompts that spark a one minute conversation or class vote. Reduce anxiety and demonstrate that retrieval is part of everyday life. (Download our free templates!)

Two Things: Ask students to retrieve and write down two things they remember from class last week or even two things they're learning in another class. Keep this quick and simple with paper or index cards.

Brain dumps: In one minute, have students write down everything they can retrieve or remember about a specific topic. For example, if students are in a World History course, ask them to write down everything they've learned about Ancient China.

Want more quick activities? Watch this video on YouTube.

Use retrieval practice in one minute or less Join us in person and virtually this fall

Learn about the science of learning at these upcoming events:

October 19–20: MassCUE in Boston, Massachusetts (hybrid, starts at $50/ticket)

Saturday, October 22: ResearchED in Frederick, Maryland (in person, $45/ticket)

Friday, November 5: Top Hat webinar (free online)

Saturday, November 12: ResearchED in Santiago, Chile (in person, $60/ticket)

A huge thanks to thousands of educators around the world who joined us this summer for our Zoom parties, Powerful Teaching book club on Facebook, virtual Q&As, and in-person workshops.

Looking for a scientist for a speaking engagement, workshop, or interview? Support our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts: invite one of these 35 cognitive scientists we feature on our website. You can sort by areas of expertise, view publications, follow them on Twitter, and email them directly.

Unleash these quick retrieval activities and join our fall events

Craving a refresher on the science of learning and teaching tips for your classroom?

Here are three resources for you:

Reach out to our featured scientists for a workshop or interview

Read our retrieval practice activities that take one minute or less

Check out the list below for my upcoming in-person and virtual events

Quick retrieval for long-term learning

Photo credit: Freepik

Retrieval practice doesn't take much classroom time – we promise. Here are our quick strategies to implement this powerful research-based strategy and improve long-term learning in your classroom:

Warm Ups: Ice breakers are okay, but Retrieval Warm Ups are better. Students retrieve their experiences with fun prompts that spark a one minute conversation or class vote. Reduce anxiety and demonstrate that retrieval is part of everyday life. (Download our free templates!)

Two Things: Ask students to retrieve and write down two things they remember from class last week or even two things they're learning in another class. Keep this quick and simple with paper or index cards.

Brain dumps: In one minute, have students write down everything they can retrieve or remember about a specific topic. For example, if students are in a World History course, ask them to write down everything they've learned about Ancient China.

Want more quick activities? Watch this video on YouTube.

Use retrieval practice in one minute or less Join us in person and virtually this fall

Learn about the science of learning at these upcoming events:

October 19–20: MassCUE in Boston, Massachusetts (hybrid, starts at $50/ticket)

Saturday, October 22: ResearchED in Frederick, Maryland (in person, $45/ticket)

Friday, November 5: Top Hat webinar (free online)

Saturday, November 12: ResearchED in Santiago, Chile (in person, $60/ticket)

A huge thanks to thousands of educators around the world who joined us this summer for our Zoom parties, Powerful Teaching book club on Facebook, virtual Q&As, and in-person workshops.

Looking for a scientist for a speaking engagement, workshop, or interview? Support our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts: invite one of these 35 cognitive scientists we feature on our website. You can sort by areas of expertise, view publications, follow them on Twitter, and email them directly.

Join our fall events and unleash these quick retrieval activities

Craving a refresher on the science of learning and teaching tips for your classroom?

Here are three resources for you:

Check out the list below for my upcoming in-person and virtual events

Reach out to our featured scientists for a workshop or interview

Read our retrieval practice activities that take one minute or less

P.S. I used to post updates weekly, I put them on pause during the earlier stages of the pandemic, and now they're back sporadically. I'm here (*waves*), just focusing energy on my teaching and my students. I appreciate your kind words, emails, and tweets!

Learn about the science of learning at these upcoming events:

October 19–20: MassCUE in Boston, Massachusetts (hybrid, starts at $50/ticket)

Saturday, October 22: ResearchED in Frederick, Maryland (in person, $45/ticket)

Friday, November 5: Top Hat webinar (free online)

Saturday, November 12: ResearchED in Santiago, Chile (in person, $60/ticket)

A huge thanks to thousands of educators around the world who joined us this summer for our Zoom parties, Powerful Teaching book club on Facebook, virtual Q&As, and in-person workshops.

Looking for a scientist for a speaking engagement, workshop, or interview? Support our diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts: invite one of these 35 cognitive scientists we feature on our website. You can sort by areas of expertise, view publications, follow them on Twitter, and email them directly.

Photo credit: Freepik

Retrieval practice doesn't take much classroom time – we promise. Here are our quick strategies to implement this powerful research-based strategy and improve long-term learning in your classroom:

Warm Ups: Ice breakers are okay, but Retrieval Warm Ups are better. Students retrieve their experiences with fun prompts that spark a one minute conversation or class vote. Reduce anxiety and demonstrate that retrieval is part of everyday life. (Download our free templates!)

Two Things: Ask students to retrieve and write down two things they remember from class last week or even two things they're learning in another class. Keep this quick and simple with paper or index cards.

Brain dumps: In one minute, have students write down everything they can retrieve or remember about a specific topic. For example, if students are in a World History course, ask them to write down everything they've learned about Ancient China.

Want more quick activities? Watch this video on YouTube.

Use retrieval practice in one minute or lessJuly 19, 2022

These are the best resources to help students study smarter, not harder

Think back to your own high school or college experience. You probably crammed, got an A, and then forgot everything. It's because easy learning is easy forgetting.

Here's how you can help students study smarter, not harder:

Share our list of the best research-based tips on how to study

Download free resources for Powerful Teaching and Make it Stick

Join our Powerful Teaching Facebook group (our summer discussion is already on Chapter 6!)

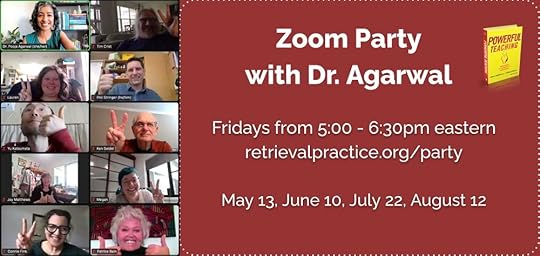

Save the date for our Zoom party on Friday, August 12

Help students study smarter, not harder

Photo by andrea piacquadio (Pexels)

Student study habits are hard to change and they're also pretty ineffective. We want students to remember, learn, and succeed. What should they do instead?

Here's our list of the best research-based books, blogs, videos, and podcasts to help your students study smarter, not harder. We especially love the resources created by our colleagues, The Learning Scientists.

What's special about our list? All of the resources are based on legit research and the tips don't require more studying. Students can take what they already do, like using flashcards, and make their study time more effective for long-term learning–without overhauling ingrained habits.

We've also included activities you can use to spark discussion with students about their study strategies. Here are three simple questions to ask students and we hope you'll share our list on Twitter (retrievalpractice.org/students).

Did you know that you can download free resources for Powerful Teaching and Make it Stick? Here's a link directly to our Google Drive. We've also got a book club discussion in our Facebook group that's in full swing, too.

For Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning, we've included free templates and figures, including our popular Neuromyths Quiz and Retrieval Guide template.

For Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning, we've got discussion questions for each chapter, recommended research articles, and sketchnotes.

Want even more summer reading? Here's our list of the top books on the science of learning, including Small Teaching, Understanding How we learn, Uncommon Sense Teaching, and more.

Join Dr. Pooja K. Agarwal, cognitive scientist, co-author of Powerful Teaching, and founder of RetrievalPractice.org, for a Zoom party Friday, August 12 from 5:00pm - 6:30pm eastern. Click here for more information.

Engage in breakout groups with educators from around the world

Live, informal, and un-recorded (Want a presentation? Watch this keynote on YouTube with Dr. Agarwal)

Stop by any time and stay for as long (or as little) as you’d like

Everyone is welcome: K–12, higher ed, non-profits, teachers, administrators, scientists, etc.

Learn more about our Zoom parties