Daniel Orr's Blog, page 43

November 25, 2021

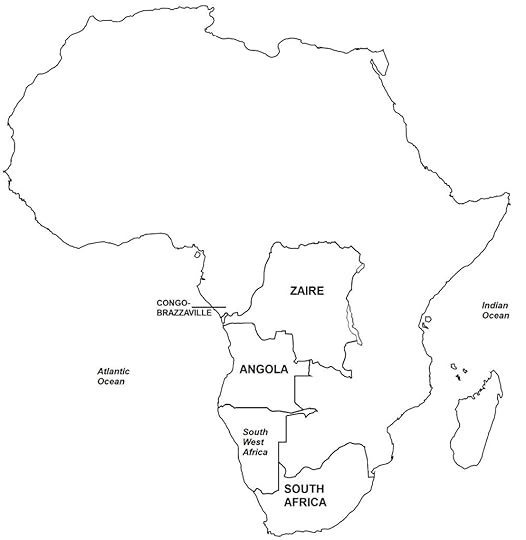

November 25, 1975 – Angolan War of Independence: Cuban forces repel a South-African led attack on Ebo

On November 25, 1975, Cuban artillery batteries stopped aSouth African-led attack on Ebo. TheSouth Africans had planned to take Luanda beforeAngola’sindependence day, which took place took weeks earlier, on November 11. After failing in this objective, by December1975, the South Africans and their Angolan allies had refocused their effortsto capturing as much territory as possible.

(Taken from Angolan War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background AfterWorld War II, thousands of Portuguese immigrants settled in Angola. The world’s prices of coffee beans were high,prompting the Portuguese government to seek new white settlers in its Africancolonies to lead the growth of agriculture. However, many of the new arrivals settled in the towns and cities,instead of braving the harsh rural frontiers. In urban areas, they competed forjobs with black Angolans who likewise were migrating there in large numbers insearch of work. The Portuguese, beingwhite, were given employment preference over the natives, producing racialtension.

The late 1940s saw the rapid growth of nationalism in Africa. In Angola,three nationalist movements developed, which were led by “assimilados”, i.e.the few natives who had acquired the Portuguese language, culture, education,and religion. The Portuguese officiallydesignated “assimilados” as “civilized”, in contrast to the vast majority ofnatives who retained their indigenous lifestyles.

The first of these Angolan nationalist movements was thePeople’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola or MPLA (Portuguese: MovimentoPopular de Libertação de Angola)led by local communists, and formed in 1956 from the merger of the Angolan CommunistParty and another nationalist movement called PLUA (English: Party of theUnited Struggle for Africans in Angola). Active in Luanda and other major urban areas, the MPLAdrew its support from the local elite and in regions populated by the Ambunduethnic group. In its formative years, itreceived foreign support from other left-wing African nationalist groups thatwere also seeking the independences of their colonies from European rule. Eventually, the MPLA fell under the influenceof the Soviet Union and other communistcountries.

The second Angolan nationalist movement was the NationalFront for the Liberation of Angola or FNLA (Portuguese: Frente Nacional deLibertação de Angola). The FNLA was formed in 1962 from the mergerof two Bakongo regional movements that had as their secondary aim theresurgence of the once powerful but currently moribund Kingdom of Congo. Primarily, the FNLA wanted to end forcedlabor, which had caused hundreds of thousands of Bakongo natives to leave theirhomes. The FNLA operated out ofLeopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) in the Congofrom where it received military and financial support from the Congolesegovernment. The FNLA was led by HoldenRoberto, whose authoritarian rule and one-track policies caused the movement toexperience changing fortunes during the coming war, and also bring about theformation of the third of Angola’snationalist movements, UNITA.

UNITA or National Union for the Total Independence of Angola(Portuguese: União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) was foundedby Jonas Savimbi, a former high-ranking official of the FNLA, overdisagreements with Roberto. Unlike theFNLA and MPLA, which were based in northern Angola, UNITA operated in thecolony’s central and southern regions and gained its main support from theOvibundu people and other smaller ethnic groups. Initially, UNITA embraced Maoist socialismbut later moved toward West-allied democratic Africanism.

War of Independence OnFebruary 3, 1961, farm laborers in Baixa do Cassanje, Malanje, rose up inprotest over poor working conditions. The protest quickly spread to many other regions, engulfing a widearea. The Portuguese were forced to sendwarplanes that strafed and firebombed many native villages. Soon, the protest was quelled.

Occurring almost simultaneously with the workers’ protest,armed bands (believed to be affiliated with the MPLA) carried out attacks in Luanda, particularly inthe prisons and police stations, aimed at freeing political prisoners. The raids were repelled, with dozens ofattackers and some police officers killed. In reprisal, government forces and Portuguese vigilante groups attacked Luanda’s slums, where theykilled thousands of black civilian residents.

In March 1961, Roberto led thousands of fighters of the UPA(Union of Peoples of Angola, a precursor organization of the FNLA) intonorthern Angola,where he incited the farmers to rise up in revolt. Violence soon broke out, where native farmerskilled hundreds of Portuguese civilians, burned farms, looted property, anddestroyed government infrastructures.

By May, the Portuguese government in Lisbonhad sent thousands of soldiers to Angola. In a brutal counter-insurgency campaign,Portuguese troops killed more than 20,000 black civilians and razed thenorthern countryside. By year’s end, thecolonial government had quelled the uprising and pushed Holden and his UPAfollowers across the border to the Congo. Some 200,000 black Angolans also fled to the Congoto escape the fighting and government retribution.

Portugal’scounter-insurgency methods were condemned by the international community. As a consequence of the uprisings, Portugal began to implement major reforms in Angola,as well as in its other African colonies. Forced labor was abolished, as was the arbitrary seizure of indigenouslands. Also for the first time, publiceducation, health care, and other social services were expanded to the generalpopulation.

November 24, 2021

November 24, 1965 – Joseph-Desire Mobutu seizes power in a coup in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

On November 24, 1965, Jose-Desire Mobutu seized power in acoup in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He would subsequentlyrule the next 32 years over a totalitarian government for. In his long reign,he mismanaged the country, which he renamed Zaire. His government corruption was corrupt, thecountry’s infrastructure was neglected, and poverty was widespread. And while the economy stagnated with a hugeforeign debt, Mobutu amassed a personal fortune of several billions of dollars.In 1972, he changed his name to Mobutu Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga(English:“The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexiblewill to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake”), shortenedto Mobutu Sese Seko, which was in line with state policy of “Zarianization” atthat time, to rid the country of vestiges of colonialism and promote a Zairianpro-African national identity.

The 1965 coup was his second. On September 14, 1960, as thenhead of the country’s armed forces, he had seized power during the CongoCrisis. The Congo Crisi was a series of civil wars that began shortly after thecountry gained its independence from Belgium on June 30, 1960. Mobutu launchedthe coup following the impasse between President Patrice Lumumba and PresidentJoseph Kasa-Vubu after Lumumba had sought Soviet support to quell aBelgian-supported uprising in Katangaand South Kasai.

In 1997, he was deposed in the First Congo War.

(Taken from First Congo War –Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background In themid-1990s, ethnic tensions rose in Zaire’s eastern regions. Zairian indigenous tribes long despised theTutsis, another ethnic tribe, whom they regarded as foreigners, i.e. theybelieved that Tutsis were not native to the Congo. The Congolese Tutsis were called Banyamulengeand had migrated to the Congoduring the pre-colonial and Belgian colonial periods. Over time, the Banyamulenge established somedegree of political and economic standing in the Congo’s eastern regions. Nevertheless, Zairian indigenous groupsoccasionally attacked Banyamulenge villages, as well as those of othernon-Congolese Tutsis who had migrated more recently to the Congo.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Congo’s eastern region was greatly destabilizedwhen large numbers of refugees migrated there to escape the ethnic violence in Rwanda and Burundi. The greatest influx occurred during theRwandan Civil War, where some 1.5 million Hutu refugees entered the Congo’sKivu Provinces (Map 17). The Huturefugees established giant settlement camps which soon came under the controlof the deposed Hutu regime in Rwanda,the same government that had carried out the genocide against RwandanTutsis. Under cover of the camps, Hutuleaders organized a militia composed of former army soldiers and civilianparamilitaries. This Hutu militiacarried out attacks against Rwandan Tutsis in the camps, as well as against theBanyamulenge, i.e. Congolese Tutsis. TheHutu leaders wanted to regain power in Rwandaand therefore ordered their militia to conduct cross-border raids from theZairian camps into Rwanda.

To counter the Hutu threat, the Rwandan government forged amilitary alliance with the Banyamulenge, and organized a militia composed ofCongolese Tutsis. The Rwandangovernment-Banyamulenge alliance solidified in 1995 when the Zairian governmentpassed a law that rescinded the Congolese citizenship of the Banyamulenge, andordered all non-Congolese citizens to leave the country.

War In October1996, the provincial government of South Kivu in Zaire ordered all Bayamulenge toleave the province. In response, theBanyamulenge rose up in rebellion. Zairian forces stepped in, only to be confronted by the Banyamulengemilitia as well as Rwandan Army units that began an artillery bombardment of South Kivu from across the border.

A low-intensity rebellion against the Congolese governmenthad already existed for three decades in Zaire. Led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the Congorebels opposed Zairian president Mobutu Sese Seko’s despotic, repressiveregime. President Mobutu had seizedpower through a military coup in 1965 and had in his long reign, grosslymismanaged the country. Governmentcorruption was widespread, the country’s infrastructure was crumbling, andpoverty and unemployment were rampant. And while Zaire’seconomy stagnated under a huge foreign debt, President Mobutu amassed apersonal fortune of several billions of dollars.

Kabila joined his forces with the Banyamulenge militia;together, they united with other anti-Mobutu rebel groups in the Kivu, with thecollective aim of overthrowing the Zairian dictator. Kabila soon became the leader of this rebelcoalition. In December 1996, with thesupport of Rwanda and Uganda,Kabila’s rebel forces won control of the border areas of the Kivu. There, Kabila formed a quasi-government thatwas allied to Rwanda and Uganda.

The Rwandan Army entered the conquered areas in the Kivu anddismantled the Hutu refugee camps in order to stop the Hutu militia fromcarrying out raids into Rwanda. With their camps destroyed, one batch of Huturefugees, comprising several hundreds of thousands of civilians, was forced tohead back to Rwanda.

Another batch, also composed of several hundreds ofthousands of Hutus, fled westward and deeper into Zaire, where many perished fromdiseases, starvation, and nature’s elements, as well as from attacks by theRwandan Army.

When the fighting ended, some areas of Zaire’s eastern provinces virtuallyhad seceded, as the Zairian government was incapable of mounting a strongmilitary campaign into such a remote region. In fact, because of the decrepit condition of the Zairian Armed Forces,President Mobutu held only nominal control over the country.

The Zairian soldiers were poorly paid and regularly stoleand sold military supplies. Poordiscipline and demoralization afflicted the ranks, while corruption was rampantamong top military officers. Zaire’smilitary equipment often was non-operational because of funding shortages. More critically, President Mobutu had becomethe enemy of Rwanda and Angola,as he provided support for the rebel groups fighting the governments in thosecountries. Other African countries thatalso opposed Mobutu were Eritrea,Ethiopia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In December 1996, Angolaentered the war on the side of the rebels after signing a secret agreement withRwanda and Uganda. The Angolan government then sent thousands ofethnic Congolese soldiers called “Katangese Gendarmes” to the KivuProvinces. These Congolese soldiers werethe descendants of the original Katangese Gendarmes who had fled to Angola in the early 1960s after the failedsecession of the Katanga Province from the Congo.

The presence of the Katangese Gendarmes greatly strengthenedthe rebellion: from Goma and Bukavu (Map 17), the Gendarmes advanced west andsouth to capture Katanga andcentral Zaire. On March 15, 1977, Kisanganifell to the rebels, opening the road to Kinshasa, Zaire’scapital. Kalemie and Kamina in Katanga Provincewere captured, followed by Lubumbashiin April. Later that month, the AngolanArmy invaded Zairefrom the south, quickly taking Tshikapa, Kikwit, and Kenge.

Kabila also joined the fighting. Backed by units of the Rwandan and UgandanArmed Forces, his rebel coalition force advanced steadily across central Zaire for Kinshasa. Kabila met only light resistance, as theZairian Army collapsed, with desertions and defections widespread in itsranks. Crowds of people in the towns andvillages welcomed Kabila and the foreign armies as liberators.

Many attempts were made by foreign mediators (United Nations, United States, and South Africa)to broker a peace settlement, the last occurring on May 16, 1977 when Kabila’sforces had reached the vicinity of Kinshasa. The Zairian government collapsed, withPresident Mobutu fleeing the country. Kabila entered Kinshasaand formed a new government, and named himself president. The First Congo War was over; the secondphase of the conflict broke out just 15 months later (next article).

November 23, 2021

November 23, 1974 – Ethiopian Civil War: The Derg military government executes sixty high-ranking officials

On November 23, 1974, inthe event known alternatively as the “Massacre of the Sixty” or “Black Saturday”, Derg security units gathered a group of imprisonedhigh-ranking ex-government and ex-military officials and executed them at theKerchele Prison in Addis Ababa. The Derg’s stated reasons for the executionswere that these officials had made “repeated plots … that might engulf thecountry into a bloodbath”, as well as “maladministration, hindering fairadministration of justice, selling secret documents of the country to foreignagents and attempting to disrupt the present Ethiopian popular movement”. Among those executed included HaileSelassie’s grandson, other members of the Ethiopian nobility, two ex-Prime Ministers,and seventeen army generals.

(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 4)

Derg seizes power InMarch 1974, a group of military officers led by Colonel AlemZewde Tessema formed the multi-unit “Armed ForcesCoordinating Committee” (AFCC) consisting of representatives from differentsectors of the Ethiopian military, tasked with enforcing cohesion among thevarious forces and assisting the government in maintaining authority in theface of growing unrest. In June 1974,reformist junior officers of the AFCC, desiring greater reforms anddissatisfied with what they saw was the AFCC’s close association with thegovernment, broke away and formed their own group.

This latter group, whichtook the name “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, andTerritorial Army, soon grew to about 110 to 120 enlisted men and officers (noneabove the rank of major) from the 40 military and security units across thecountry, and elected Majors Mengistu Haile Mariam and Atnafu Abate as its chairman and vice-chairman,respectively. This group, which becameknown simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning“Committee” or “Council”), had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit forvarious military and police units in order to maintain peace and order, andalso to uphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, discipliningerrant officers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Derg operated anonymously(e.g. its members were not publicly known initially), but worked behind suchpopulist slogans as “Ethiopia First”, “Land to the Peasants”, and “Democracyand Equality to all” to gain broad support among the military and generalpopulation. By July 1974, the Derg’spower was felt not only within the military but in the government itself, andHaile Selassie was forced to implement a number of political measures,including the release of political prisoners, the return of political exiles tothe country, passage of a new constitution, and more critically, to allow Dergto work closely with the government. Under Derg pressure, the government of PrimeMinister Makonnen collapsed; succeeding as Prime Minister wasMikael Imru, an aristocrat who held leftist ideas.

Haile Selassie’s concessions to the Derg includedmeasures to investigate government corruption and mismanagement. In the period that followed, Derg arrestedand imprisoned many high-ranking imperial, administrative, and militaryofficials, including former Prime Ministers Habte-Wold and Makonnen,Cabinet members, military generals, and regional governors. In August 1974, a proposed constitution thatcalled for establishing a constitutional monarchy was set aside. Now operating virtually with impunity, theDerg took aim at the imperial court, dissolving the imperial governing councilsand royal treasury, and seizing royal landholdings and commercial assets. By this time, Haile Selassie’s governmentvirtually had ceased to exist; de factopower was held by the military, or more precisely, by Derg.

The culmination of events occurred when HaileSelassie was accused of deliberately denying the existence of a widespreadfamine that currently was ravaging Ethiopia’s Wollo province, whichalready had killed some 40,000 to 80,000 to as many as 200,000 people. Conflicting reports indicated that HaileSelassie was not aware of the famine, was fully aware of it, or that governmentadministrators withheld knowledge of its existence from the emperor. By August 1974, large protest demonstrationsin Addis Ababawere demanding the emperor’s arrest. Finally on September 12, 1974, the Derg overthrew Haile Selassie in abloodless coup, leading away the frail, 82-year old ex-monarch to imprisonment.

The Derg gained control of Ethiopia but did not abolish themonarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, HaileSelassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment, was to succeedto the throne as the new “king” on his return to the country. However, Prince Wossen rejected the offer andremained abroad. The Derg then withdrewits offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether, thus ending the800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (OnAugust 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassie passedaway under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating that complications froma medical procedure had caused his death, while critics alleging that theex-monarch was murdered.)

Ethiopia’s Provinces during the Ethiopian Civil War

The surreptitious means by which Derg, in a periodof six months, gained power by progressively dismantling the Ethiopian Empireand ultimately deposing Haile Selassie, sometimes is referred to as the“creeping coup” in contrast with most coups, which are sudden and swift. On September 15, 1974, Derg formally tookcontrol of the government and renamed itself as the Provisional MilitaryAdministrative Council (although it would continue to be commonlyknown as Derg), a ruling military junta under General Aman Andom, a non-memberDerg whom the Derg appointed as its Chairman; General Aman thereby also assumedthe role of Ethiopia’s head of state.

At the outset, Derg had its political leaningsembodied in its slogans “Ethiopia First” (i.e. nationalism) and “Democracy andEquality to all”. Soon, however, itabolished the Ethiopian parliament, suspended the constitution, and ruled bydecree. In early 1975, Derg launched aseries of broad reforms that swept away the old conservative order and beganthe country’s transition to socialism. In January-February 1975, nearly all industries were nationalized. In March, an agrarian reform programnationalized all farmlands (including those owned by the country’s largestlandowner, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church), reduced farm sizes, and abolishedtenancy farming. Collectivizedagriculture was introduced and farmers were organized into peasantorganizations. (Land reform was fiercelyresisted in such provinces as Gojjam, Wollo, and Tigray, where most farmersowned their lands and tenant farming was not widely practiced.) In July 1975, all urban lands, houses, andbuildings were nationalized and city residents were organized into urbandwellers’ associations, known as “kebeles”, which would play a major role in thecoming civil war. Despite the extensive nationalization, a few private sector industries that wereconsidered vital to the economy were left untouched, e.g. the retail andwholesale trade, and import and export industries.

In April 1976, Dergpublished the “Program for the National Democratic Revolution”, which outlinedthe regime’s objectives of transforming Ethiopia into a socialist state, withpowers vested in the peasants, workers, petite bourgeoisie, and anti-feudal andanti-monarchic sectors. An agency calledthe “Provisional Office for Mass Organization Affairs” was established to workout the transformative process toward socialism.

November 22, 2021

November 22, 1940 – World War II: Greek counter-attack advances into Albania

In early November 1940, Greekforces began to launch small counter-attacks from Epirusand western Macedonia. Then with the arrival of strongreinforcements, on November 14, the Greeks launched a major offensive inwestern Macedonia in thedirection of Korce inside Albania. The Greeks navigated through the higherterrain to avoid the enemy armor and using stealth, they surprised the Italiansand broke through on November 22, 1940 and seized the Korce Plateau. The Italians were forced to retreat to avoidbeing encircled. The Greeks thenexpanded their offensive all across the front; by November 23, they hadrecaptured all their previously lost territory and were advancing into Albaniafrom east to west of the line. InNovember-December 1940, the Greeks held the initiative and captured severalareas in Albania,including Erseka (November 21), Pogradec (December 29). Permeti (December 3),Sarande (December 5), Argyrokastro and Delvino (December 8), and Himara(December 22). By the second half ofDecember 1940, the Greeks halted their offensive because of supply problemscaused by an overextended line; as well, success for the Greeks had come at ahigh price in personnel losses.

(Taken from Greco-Italian War – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Background Mussoliniwas ready to build an Italian Empire, with his attention focused on the Balkanswhich he saw as falling inside the Italian sphere of influence. He also longed to gain mastery of the Mediterranean Sea in the Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”)concept, and turn it into an “Italian lake”. He chafed at Italy’sgeographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, likening it to being shut in and imprisoned by the Britishand French, who controlled much of the surrounding regions and possessed morepowerful navies. Mussolini wasdetermined to expand his own navy and gain dominance over southern Europe andnorthern Africa, and ultimately build an empire that would stretch from the Strait of Gibraltarat the western tip of the Mediterranean Sea to the Strait of Hormuz near the Persian Gulf.

Meanwhile, Greece had become alarmed by the Italianinvasion of Albania. Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas, whoironically held fascist views and was pro-German, turned to Britain for assistance. The British Royal Navy, which had bases inmany parts of the Mediterranean, including Gibraltar,Malta, Cyprus, Egypt,and Palestine, then made security stops in Crete and other Greek islands.

Italian-Greek relations,which were strained since the late 1920s by Mussolini’s expansionist agenda,deteriorated further. In 1940, Italy initiated an anti-Greek propagandacampaign, which included the demand that the Greek region of Epirus must be ceded to Albania, since it contained a largeethnic Albanian population. The Epirus claim was popular among Albanians, whooffered their support for Mussolini’s ambitions on Greece. Mussolini accused Greece of being a British puppet,citing the British naval presence in Greek ports and offshore waters. In reality, he was alarmed that the BritishNavy lurking nearby posed a direct threat to Italyand hindered his plans to establish full control of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas.

Italy then launched armed provocations against Greece, which included several incidents inJuly-August 1940, where Italian planes attacked Greek vessels at Kissamos, Gulfof Corinth, Nafpaktos, and Aegina. On August 15, 1940, an undetected Italiansubmarine sank the Greek light cruiser Elli. Greek authorities found evidence that pointedto Italian responsibility for the Ellisinking, but Prime Minister Metaxas did not take any retaliatory action, as hewanted to avoid war with Italy.

Also in August 1940,Mussolini gave secret orders to his military high command to start preparationsfor an invasion of Greece. But in a meeting with Hitler, Mussolini wasprevailed upon by the German leader to suspend the invasion in favor of theItalian Army concentrating on defeating the British in North Africa. Hitler wasconcerned that an Italian incursion in the Balkans would worsen the perennialstate of ethnic tensions in that region and perhaps prompt other major powers,such as the Soviet Union or Britain,to intervene there. The Romanian oilfields at Ploiesti, which were extremely vitalto Germany,could then be threatened. In August1940, unbeknown to Mussolini, Hitler had secretly instructed the Germany military high command to draw up plansfor his greatest project of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union. And for thismonumental undertaking, Hitler wanted no distractions, including one in theBalkans. In the fall of 1940, Mussolinideferred his attack on Greece,and issued an order to demobilize 600,000 Italian troops.

Then on October 7, 1940,Hitler deployed German troops in Romania at the request of the newpro-Nazi government led by Prime Minister Ion Antonescu. Mussolini, upon being informed by Germany four days later, was livid, as hebelieved that Romaniafell inside his sphere of influence. More disconcerting for Mussolini was that Hitler had again initiated amajor action without first notifying him. Hitler had acted alone in his conquests of Poland,Denmark, Norway, France,and the Low Countries, and had given notice tothe Italians only after the fact. Mussolini was determined that Hitler’s latest stunt would bereciprocated with his own move against Greece. Mussolini stated, “Hitler faces me with afait accompli. This time I am going topay him back in his own coin. He will find out from the papers that I haveoccupied Greece.In this way, the equilibrium will be re-established.”

On October 13, 1940 andsucceeding days, Mussolini finalized with his top military commanders theimmediate implementation of the invasion plan for Greece, codenamed“Contingency G”, with Italian forces setting out from Albania. A modification was made, where an initialforce of six Italian divisions would attack the Epirus region, to be followed bythe arrival of more Italian troops. Thecombined forces would advance to Athens andbeyond, and capture the whole of Greece. The modified plan was opposed by GeneralPietro Badoglio, the Italian Chief of Staff, who insisted that the originalplan be carried out: a full-scale twenty-division invasion of Greece with Athens as the immediate objective. Other factors cited by military officers whowere opposed to immediate invasion were the need for more preparation time, therecent demobilization of 600,000 troops, and the inadequacy of Albanian portsto meet the expected large volume of men and war supplies that would be broughtin from Italy.

But Mussolini would not bedissuaded. His decision to invade wasgreatly influenced by three officials: Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano(who was also Mussolini’s son-in-law), who stated that most Greeks detestedtheir government and would not resist an Italian invasion; the ItalianGovernor-General of Albania Francesco Jacomoni, who told Mussolini thatAlbanians would support an Italian invasion in return for Epirus being annexedto Albania; and the commander of Italian forces in Albania General SebastianoPrasca, who assured Mussolini that Italian troops in Albania were sufficient tocapture Epirus within two weeks. Thesethree men were motivated by the potential rewards to their careers that anItalian victory would have; for example, General Prasca, like most Italianofficers, coveted being conferred the rank of “Field Marshall”. Mussolini’s order for the invasion had thefollowing objectives, “Offensive in Epirus,observation and pressure on Salonika, and in a second phase, march on Athens”.

On October 18, 1940,Mussolini asked King Boris II of Bulgariato participate in a joint attack on Greece,but the monarch declined, since under the Balkan Pact of 1934, other Balkancountries would intervene for Greecein a Bulgarian-Greek war. Deciding thatits border with Bulgaria wassecure from attack, the Greek government transferred half of its forcesdefending the Bulgarian border to Albania; as well, all Greekreserves were deployed to the Albanian front. With these moves, by the start of the war, Greek forces in Albaniaoutnumbered the attacking Italian Army. Greecealso fortified its Albanian frontier. And because of Mussolini’s increased rhetoric and threats of attack, bythe time of the invasion, the Italians had lost the element of surprise.

November 21, 2021

November 21, 1962 – Sino-Indian War: China’s announcement of a unilateral ceasefire takes effect, ending hostilities

On November 19, 1962, Premier Zhoudeclared a unilateral ceasefire, which took effect two days later, November 21,when Chinese forces withdrew 20 kilometers from their most advanced positions.The 32-day war was over, although skirmishes continued for a short timethereafter. War casualties included, onthe Indian Army side, some 1,300 killed, 1,000 wounded, 1,700 missing, and 4,000captured; and on the Chinese side, some 700 killed and 1,700 wounded.

(Taken from Sino-Indian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

AftermathThe Sino-Indian War was a resounding victory for the PLA, which it achievedusing speed and surprise, concentration of force, innovative and flexibletactics, efficient logistics, and mastery of terrain and weatherconditions. By contrast, the Indian Armysuffered from poor military leadership, insufficient logistics, inadequatedefense, and bad strategy. As a result,the PLA gained full control of Aksai Chin,but withdrew from NEFA, where itallowed the Indian Army and the Indian civilian government to reestablish theirauthority there.

For India, the war had a profoundeffect. Prime Minister Nehru was severely criticized for his pacifistattitude toward China,while Defense Minister V.K. Krishna Menon was forced to resign. India-China relations deteriorated, and in India,a rise of nationalism and anti-Chinese sentiment came upon the generalpopulation.

The Indian government launched a fullreview of its military infrastructure and capability, starting with afact-finding commission led by two Indian Army generals, T.B. Henderson Brooks and PremindraSingh Bhagat, who subsequently compiled the Henderson Brooks-Bhagat Report,which assessed the Indian Army’s performance in the war. Although the report has remained classified,in the period that followed, the Indian Armed Forces underwent majorimprovements: manpower strength was increased, military doctrine andorganizational structure were revised, modern weapons were purchased, etc.

The India-China border issue has sinceremained unresolved, with the Line of Actual Control (LAC), serving as the de facto India-China border in AksaiChin and NEFA; at NEFA, the LAC isequivalent to the McMahon Line. Before the war, Pakistanalso shared a disputed border with China in the Gilgit-Baltistan –Aksai Chin regions. On October 13, 1962,one week before the Sino-Indian War began, Pakistani and Chineserepresentatives met to negotiate a border settlement, which was achieved with aborder agreement between the two countries on March 2, 1963.

In the years following the war, anumber of border incidents have occurred between Indian and Chineseforces. In 1967, fighting broke outtwice in Sikkim, an Indianprotectorate not recognized by China. In both cases, PLA units which launched theattacks were beaten back. Sikkim subsequently (in 1975) was incorporatedas an Indian state and later (in 2003) recognized as such by China.

Then in 1986-1987, in India-controlledNEFA (also claimed by China),PLA units occupied the Sumdorong Chu Valley,triggering a build-up of forces by both sides in late 1986 until early1987. Tensions increased further when inDecember 1986, Indiadeclared NEFA as an Indian state, named ArunachalPradesh. In May 1987, tensions easedwhen the Indian External Affairs Minister visited China. The following year, Indian Prime MinisterRajiv Gandhi also visited China.

Over the years, security along theIndia-China border has remained tight, with occasional reports of smallinfiltration operations and other border violations taking place. Indiaand China have establishedfour Border Personnel Meeting (BPM) points (at Chushul in Ladakh, Nathu La in Sikkim, Bum La Pass in Tawang, ArunachalPradesh, and Lipulekh Pass in Uttarakhand)where Indian and Chinese military representatives meet regularly to discuss andresolve border incidents. Furthermore, India and China have signed a number ofagreements aimed at preventing another war, including the 1993 and 1996treaties called the Sino-Indian Bilateral Peace and Tranquility Accords.

November 20, 2021

November 20, 1910 – Mexican Revolution: Defeated candidate Francisco I. Madero calls for the overthrow of President Porfirio Diaz, starting the revolution

On November 5, 1910, defeated presidential candidateFrancisco I. Madero, who had escaped from prison, wrote and issued the Plan de San Luis, where he called on theMexican people to rise up in rebellion against President Porfirio Diaz. (InMexican politics, a Plan is adeclaration of principles that accompanies a (usually) armed uprising againstthe national government.)

The Plan calledfor the rebellion to start on November 20, 1910, nullified the 1910 election ofPorfirio Diaz citing electoral fraud, and stipulated a provisional governmentwith Madero as president. Diaz’s government was also condemned as dictatorial,corrupt, and the cause for the deplorable socio-economic conditions of thepeople.

(Taken from Mexican Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background Duringthe early 1900s, Mexicoexperienced increasing levels of prosperity. Mexican president Porifirio Diaz’s thirty-year rule had achieved highlevels of economic growth, allowing the country to make rapid strides to fullindustrialization. Foreign investmentsfrom the United States and Europe were boosting the local economy. The country’s natural resources were beingdeveloped, agricultural plantations yielded rich harvests, and urban centersshowed many signs of progress.

Deep within, however, Mexico’s society was rife withdiscontent. Wealth remained with andgrew only with the small ruling elite. Workers, peasants, and villagers were extremely poor. Land ownership was grossly disproportionate –5% of the population owned 95% of all lands. Perhaps as many as 90% of Mexicans were peasants who did not own landand were completely dependent on the plantation owners. Some very wealthy landowners owned vasttracts of land that covered many hundreds of thousands of acres; however, theirfarm workers were paid token wages and lived in miserable conditions.

Landowners dealt ruthlessly with disloyal peasants. President Diaz also wanted the status quo andthus kept all forms of dissent in check with his army, paramilitaries, andbands of thugs. Mexico outwardly was a practicingdemocracy; however, President Diaz always manipulated the elections in hisfavor and often used the army and paramilitaries to rein in the politicalopposition.

Mexico’spresidential election of 1910 appeared to be no different from the past, asPresident Diaz again prevailed by resorting to electoral fraud. Francisco Madero, the main oppositionpresidential contender, escaped from prison and called on the people to rise upin rebellion. Madero promised to bringabout major social and economic reforms, which appealed to the masses whorushed to join the many rebel groups that had sprung up.

War In November1910, fighting broke out, first with intermittent, disorganized firefightsbetween government troops and rebels groups that soon escalated into full-scalebattles in many parts of the country. The various rebel movements were led by revolutionaries who weremotivated partly by personal ambitions, but with the collective desire tooverthrow the government and implement major socio-economic reforms.

During the revolution’s early stages, the most prominentrebel leaders included Pascual Orozco and Francisco Villa from the northern province of Chihuahua,and Emiliano Zapata from the southern province of Morelos(Map 35). The rebels dealt successivedefeats on the government’s forces. Thenwith the fall of Ciudad Juarezto the rebels in May 1911, President Diaz abdicated and fled into exile.

Madero and the other rebel leaders triumphantly entered Mexico City, the country’scapital, where they were greeted as liberators by large, enthusiasticcrowds. Then in the general electionsheld in November 1911, Madero became Mexico’s new president. While in office, however, President Maderoappeared to be in no hurry to carry out the promised reforms, but instituted apolicy of national reconciliation. Beingan aristocrat who descended from a landowning family, President Madero retainedthe previous regime’s political bureaucracy, which was composed of wealthypoliticians. At the same time, hecontinued to promise the rebel leaders, most of whom were poor, that majorreforms were coming. Soon, the rebelleaders became disillusioned, leading many of them to return to their regionsand restart the revolution.

While each revolutionary leader wanted varying levels ofreforms, even the return of the country to the socially progressive 1857national constitution, Zapata, in particular, was angered by President Madero’sprocrastination and apparent non-commitment to bring about the reforms. Zapata wanted a complete overhaul of thesocial and economic systems, starting with the government’s return ofexpropriated ancestral lands to the indigenous people. Zapata also demanded that the largeagricultural estates be broken up and distributed to landless peasants andfarmers.

November 19, 2021

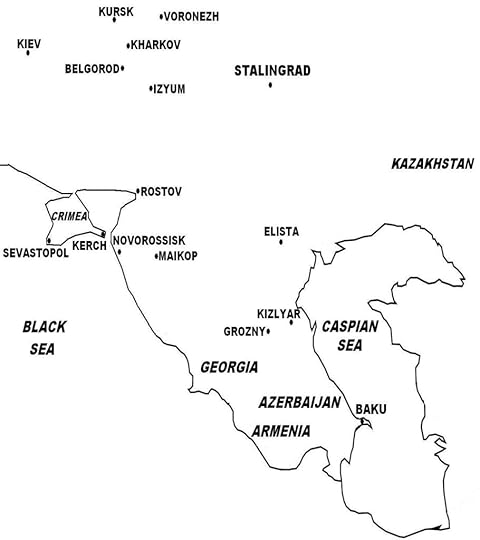

November 19, 1942 – World War II: Soviet forces trap German 6th Army in Stalingrad

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet Red Army launched OperationUranus, which led to the encirclement of German 6th Army in Stalingrad. Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previousmonths, the Soviet High Command had been sending large numbers of Red Armyformations to the north and southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some 250,000-300,000troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

⅔

(Taken from Battle of Stalingrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Meanwhile to the north, German Army Group B, tasked withcapturing Stalingrad and securing the Volga, began its advance to the Don River on July 23, 1942. The German advance was stalled by fierceresistance, as the delays of the previous weeks had allowed the Soviets tofortify their defenses. By then, theGerman intent was clear to Stalin and the Soviet High Command, which thenreorganized Red Army forces in the Stalingradsector and rushed reinforcements to the defense of the Don. Not only was German Army Group B delayed bythe Soviets that had began to launch counter-attacks in the Axis’ northernflank (which were held by Italian and Hungarian armies), but also byover-extended supply lines and poor road conditions.

On August 10, 1942, German 6th Army had moved to the westbank of the Don, although strong Soviet resistance persisted in the north. On August 22, German forces establishedbridgeheads across the Don, which was crossed the next day, with panzers andmobile spearheads advancing across the remaining 36 miles of flat plains to Stalingrad. OnAugust 23, German 14th Panzer Division reached the VolgaRiver north of Stalingradand fought off Soviet counter-attacks, while the Luftwaffe began a bombingblitz of the city that would continue through to the height of the battle, whenmost of the buildings would be destroyed and the city turned to rubble.

On August 29, 1942, two Soviet armies (the 62nd and 64th) barelyescaped being encircled by the German 4th Panzer Army and armored units ofGerman 6th Army, both escaping to Stalingrad and ensuring that the battle forthe city would be long, bloody, and difficult.

On September 12, 1942, German forces entered Stalingrad, starting what would be a four-month longbattle. From mid-September to earlyNovember, the Germans, confident of victory, launched three major attacks tooverwhelm all resistance, which gradually pushed back the Soviets east towardthe banks of the Volga.

By contrast, the Soviets suffered from low morale, but werecompelled to fight, since they had no option to retreat beyond the Volga because of Stalin’s “Not one step back!”order. Stalin also (initially) refusedto allow civilians to be evacuated, stating that “soldiers fight better for analive city than for a dead one”. Hewould later allow civilian evacuation after being advised by his top generals.

Soviet artillery from across the Volgaand cross-river attempts to bring in Red Army reinforcements were suppressed bythe Luftwaffe, which controlled the sky over the battlefield. Even then, Soviet troops and suppliescontinued to reach Stalingrad, enough to keepup resistance. The ruins of the cityturned into a great defensive asset, as Soviet troops cleverly used the rubbleand battered buildings as concealed strong points, traps, and killingzones. To negate the Germans’ airsuperiority, Red Army units were ordered to keep the fighting lines close tothe Germans, to deter the Luftwaffe from attacking and inadvertently causingfriendly fire casualties to its own forces.

The battle for Stalingradturned into one of history’s fiercest, harshest, and bloodiest struggles forsurvival, the intense close-quarter combat being fought building-to-buildingand floor-to-floor, and in cellars and basements, and even in the sewers. Surprise encounters in such close distancessometimes turned into hand-to-hand combat using knives and bayonets.

By mid-November 1942, the Germans controlled 90% of thecity, and had pushed back the Soviets to a small pocket with four shallowbridgeheads some 200 yards from the Volga. By then, most of German 6th Army was lockedin combat in the city, while its outer flanks had become dangerouslyvulnerable, as they were protected only by the weak armies of its Axispartners, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians. Two weeks earlier, Hitler, believingStalingrad’s capture was assured, redeployed a large part of the Luftwaffe tothe fighting in North Africa.

Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months, the SovietHigh Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formations to the northand southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

The German High Command asked Hitler to allow the trappedforces to make a break out, which was refused. Also on many occasions, General Friedrich Paulus, commander of German6th Army, made similar appeals to Hitler, but was turned down. Instead, on November 24, 1942, Hitler advisedGeneral Paulus to hold his position at Stalingraduntil reinforcements could be sent or a new German offensive could break theencirclement. In the meantime, thetrapped forces would be supplied from the air. Hitler had been assured by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering that the 700tons/day required at Stalingrad could bedelivered with German transport planes. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to deliver the needed amount, despitethe addition of more transports for the operation, and the trapped forces in Stalingrad soon experienced dwindling supplies of food,medical supplies, and ammunition. Withthe onset of winter and the temperature dropping to –30°C (–22°F), anincreasing number of Axis troops, yet without adequate winter clothing, sufferedfrom frostbite. At this time also, theSoviet air force had began to achieve technological and combat parity with theLuftwaffe, challenging it for control of the skies and shooting down increasingnumbers of German planes.

Meanwhile, the Red Army strengthened the cordon aroundStalingrad, and launched a series of attacks that slowly pushed the trappedforces to an ever-shrinking perimeter in an area just west of Stalingrad.

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to breakout. Hitler and General Paulus bothrefused. General Paulus cited the lackof trucks and fuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, andthat his continued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Sovietforces which would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

Meanwhile in Stalingrad, byearly January 1943, the situation for the trapped German forces grewdesperate. On January 10, the Red Armylaunched a major attack to finally eliminate the Stalingradpocket after its demand to surrender was rejected by General Paulus. On January 25, the Soviets captured the lastGerman airfield at Stalingrad, and despite theLuftwaffe now resorting to air-dropping supplies, the trapped forces ran low onfood and ammunition.

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, on February 2,General Paulus surrendered to the Red Army, along with his trapped forces,which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle of Stalingrad, one of thebloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axis losing 850,000 troops, 500tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; and the Soviets losing 1.1million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 2,800 planes. The German debacle at Stalingrad andwithdrawal from the Caucasus effectively endedCase Blue, and like Operation Barbarossa in the previous year, resulted inanother German failure.

November 18, 2021

November 18, 1961 – Vietnam War: U.S. President John F. Kennedy sends military advisors to South Vietnam

Initially, U.S. PresidentJohn F. Kennedy Kennedy had been reluctant to become involved in Vietnam, but with the growing Cold War crisis inIndochina that threatened to undermine American political credibility globally,he decided to increase military support to South Vietnam. The numberof military advisers was greatly increased, from 900 to 16,000 over the courseof his presidency.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

JFK and the Vietnam War President John F. Kennedy, who in January 1961 succeeded Eisenhower, was faced with a number of Cold War crises in hisfirst year in office, including the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in Cuba (April 1961), and theBerlin Crisis (June –November 1961). PresidentKennedy initially had been reluctant to become involved in Vietnam, but with the growing Cold War crisis inIndochina that threatened to undermine American political credibility globally,he decided to increase military support to South Vietnam. The numberof military advisers was greatly increased, from 900 to 16,000 over the courseof his presidency. President Kennedyadopted a number of counter-insurgency initiatives which the British Army haddeveloped in the 1950s, and which had proved successful during the MalayanEmergency (separate article): 1.Counter-insurgency warfare – U.S. Special Forces (“Green Berets”) trained theSouth Vietnamese military in anti-insurgency combat, and later also organizedethnic minorities in the Central Highlands into guerilla militias to fight theViet Cong; 2. The use of herbicides and defoliants – U.S.planes sprayed many types of herbicides and defoliants, more usually AgentOrange, to deprive the insurgents of jungle cover andfood crops, and clear vegetation along road and water routes; and 3. Forcedresettlement in rural areas – Villages in the countryside were depopulated andtheir residents forced to relocate into government-designated camps under theStrategic Hamlet Program.

In theStrategic Hamlet Program which peakedin 1962-1963, over 8 million South Vietnamese people were relocated to 8,000protected villages called “hamlets”, in order to separate the rural populationfrom the Viet Cong/NLF, and thus deprive the rebels of their main sourceof food, supplies, information, and recruits. The Hamlet program was extremely unpopular among the affectedpopulation, since it forcibly resettled civilians away from their traditionalancestral and burial grounds (Vietnamese are predominantly Buddhists whopractice ancestral worship), and also because the hamlets suffered frominadequate public facilities, and more crucially, lack of securityprotection. Hamlets located in VietCong-controlled areas were extremely vulnerable to rebel attacks, and the SouthVietnamese military was unable, even unwilling, to confront these attacks. By late 1963, the Hamlet program was indecline and ceased completely in 1964, when the hamlets were abandoned and thevillagers returned to their former areas to rebuild their villages, or becamerefugees in Saigon and other urban centers.

Because ofthe perceived threat of an invasion by Chinaor North Vietnam into theinsurgency-weakened South Vietnam, the U.S.military made plans to deploy U.S.combat troops in South Vietnam. However, President Kennedy was reluctant to do so, believing that afully capable South Vietnamese military (with U.S. military guidance and support)was more than sufficient to quell the Viet Cong insurgency,and that introducing U.S. ground troops should be done only as a lastresort. He did send U.S. pilots, who flew U.S. military helicopters thattransported South Vietnamese troops to the battlefield.

In 1963, thepolitical climate in South Vietnam deterioratedconsiderably, and opposition rose against the graft-ridden Diemgovernment. President Diem, a Roman Catholic in an overwhelmingly Buddhistcountry, appointed many Catholics to top government and military positions,angering Buddhists. Then in May 1963, ina Buddhist streetprotest condemning the government’s ban on raising Buddhist flags on Vesak(Buddha Day), security forces opened fire on the crowd, killing ninepeople. The next month, in protest, aBuddhist monk committed self-immolation by setting himself on fire, this eventbeing captured on camera by a news reporter, with the photograph shocking theinternational community. In the followingmonths, other Buddhist monks also set themselves on fire, and widespreadprotests erupted in Saigon.

Then inAugust 1963, South Vietnamese Special Forces raided Buddhist temples, killingand arresting hundreds of Buddhists and causing extensive property damage. The United States, by this time greatly alarmed at South Vietnam’s deteriorating situation, began to distanceitself from President Diem. In particular, the Kennedyadministration was outraged at Ngo Dinh Nhu, the president’s younger brotherand chief advisor, who it believed was behind the South Vietnamese government’soppressive policies. The U.S.government had pressed President Diem to dismissNhu and stop the repression. But with noreforms coming and South Vietnam’ssecurity situation deteriorating, the United States tacitly gave itsconsent to a plot by South Vietnamese generals to overthrow the Diem government. In a coup on November 1–2, 1963, Diem wasshot and killed, together with Nhu. Amilitary junta led by high-ranking officers was then installed to rule thecountry.

Meanwhile in1962, the South Vietnamese military had begun to make progress in suppressingthe Viet Cong. GeneralPaul Harkins, commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam (which wasofficially called Military Assistance Command, Vietnam or MACV), announced thatthe Viet Cong would be defeated by December 1963, by which time Americanadvisers could be withdrawn from South Vietnam. However, in January 1963, at the Battle of Ap Bac, the Viet Cong scored a stunning victory over thenumerically superior (by a 4:1 ratio) South Vietnamese Army. The Viet Cong had developed new tactics tocounter the enemy’s modern weapons, and held its ground against SouthVietnamese forces that attacked using air, mechanized, and artillery support.

In 1963-1964,the Viet Cong/NLF expanded considerably: its forces, nownumbering over 100,000 fighters, consisted of both regular and guerilla units,and were increasingly capable of fighting conventional battles. By then, the Viet Cong/NLF controlled or hadinfluence over vast areas from the Central Highlands to the Mekong Delta (areasit called “liberated zones”), or nearly 50% of South Vietnam’s land area, and 50% of the total population. There, it set up quasi-governments in localvillages, which collected taxes from the residents and distributed agriculturallands to the peasants. The Ho Chi Minh Trail alsohad grown extensively, allowing thousands of North Vietnamese Army soldiers tomove south and join the war against South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese Army operated innorthern South Vietnamwhile the Viet Cong/NLF, aided by some North Vietnamese Army units, operated inthe other areas.

In the aftermath ofDiem’s overthrow, South Vietnam experiencedpolitical instability by a series of military coups, where juntas were formedand were toppled one after the other. The South Vietnamese military was plagued with corruption, and sufferedfrom low morale and poor combat capability.

November 17, 2021

November 17, 1970 – Vietnam War: U.S. Army Lt. William Calley goes on court-martial trial for the My Lai Massacre

On November 17, 1970, U.S. Army Lt. William Calley went oncourt-martial trial for the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War. He was oneof 26 officers and men charged for the crime. In March 1971, Lt. Calley was theonly officer found guilty for the killing of 22 villagers and was handed down alife sentence. In August 1971, his sentence was reduced to twenty years. InSeptember 1974, he was paroled by the U.S. Army after serving three andone-half years under house arrest in a military base.

The My Lai Massacre occurred on March 16, 1968 when a U.S.Army Company descended on the hamlets of My Laiand My Khe and killed some 350 to 500 civilians (men, women, children, andinfants). The massacre has been described “the most shocking episode of theVietnam War”.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Before the Cambodian Campaign began, President Nixon hadannounced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to theoperation. Within days, largedemonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States,with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio,National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four peopleand wounding eight others. This incidentsparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across thecountry. Anti-war sentiment already wasintense in the United Statesfollowing news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My LaiMassacre, where U.S. troopson a search and destroy mission descended on My Laiand My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including womenand children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officiallytitled: United States– Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense),a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked tothe press. The Pentagon Papers showedthat successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman,Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many timesmisled the American people regarding U.S.involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stopthe document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. SupremeCourt subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publicationcontinued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and othernewspapers.

As in Cambodia,the U.S. high command hadlong desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logisticalportion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality,the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laosand intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secretMilitary Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOGthat involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. AirForce, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged PresidentNixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited Americanground troops from entering Laos,South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho ChiMinh Trail, with U.S. forcesonly playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combatcapability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.

In February-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the SouthVietnamese Army, (some of whom were transported by U.S.helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launchedOperation Lam Son 719 into southeastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the SouthVietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, a strategic logistical hubof the Ho Chi Minh Trail located 25 miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The main South Vietnamese column was stoppedby heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some 15 milesfrom the border. North Vietnameseforces, initially distracted by U.S.diversionary attacks elsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the SouthVietnamese, and counterattacked. NorthVietnamese artillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several SouthVietnamese firebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S.air transport operations. By early March1971, the attack was called off, and with the North Vietnamese intensifyingtheir artillery bombardment, the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into achaotic retreat and a desperate struggle for survival. The operation was a debacle, with the SouthVietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% of their tanks, 50% of theirarmored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces; North Vietnamese casualtieswere 2,000 killed. American planes weresent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor, transports, and equipment toprevent their capture by the enemy. U.S.air losses were substantial: 84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168helicopters destroyed and 618 damaged.

Buoyed by this success, in March 1972, North Vietnam launched the Nguyen Hue Offensive(called the Easter Offensive in the West), its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam,using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armored vehicles. By this time, South Vietnamese forces carriedpractically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soonscheduled to leave. North Vietnameseforces advanced along three fronts. Inthe northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and capturedthe northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a South Vietnamesecounterattack, supported by U.S.air firepower, including B-52 bombers, recaptured most of the occupiedterritory, including Quang Tri, near the northern border. In the Central Highlands front, the NorthVietnamese objective to advance right through to coastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnamin two, failed to break through to Kontum and was pushed back. In the southern front, North Vietnameseforces that advanced from the Cambodian border took Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, butwere repulsed at An Loc because of strong South Vietnamese resistance andmassive U.S.air firepower.

To further break up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April1972, U.S. planes including B-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train,launched bombing attacks mostly between the 17th and 19th parallels in NorthVietnam, targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plantsand industrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads,bridges, and railroad tracks. In May1972, the bombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, whereAmerican planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval minesoff the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

At the end of the Easter Offensive in October 1972, NorthVietnamese losses included up to 130,000 soldiers killed, missing, or woundedand 700 tanks destroyed. However, NorthVietnamese forces succeeded in capturing and holding about 50% of theterritories of South Vietnam’snorthern provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien,Quang Nam,and Quang Tin, as well as the western edges of II Corps and III Corps. But the immense destruction caused by U.S. bombing in North Vietnam forced the latter to agree to make concessions atthe Paris peacetalks.

At the height of North Vietnam’sEaster Offensive, the Cold War took a dramatic turn when in February 1972,President Nixon visited Chinaand met with Chairman Mao Zedong. Thenin May 1972, President Nixon also visited the Soviet Unionand met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders. A period of superpower détente followed. Chinaand the Soviet Union, desiring to maintain their newly established friendlyrelations with the United States,aside from issuing diplomatic protests, were not overly provoked by the massiveU.S. bombing of North Vietnam. Even then, the two communist powers stood bytheir North Vietnamese ally and continued to send large amounts of militarysupport.

November 16, 2021

November 16, 1912 – First Balkan War: Serbian and Ottoman forces clash at the Battle of Bitola

On November 16, 1912, Serbian forces pushed into Bitola, starting anintense three-day battle during the First Balkan War. The Ottomans were defeated, and forced toabandon the whole the province and retreat to the Berat region in centralAlbania, as well as to the fortress city of Ioannina, which was then undersiege by the Greek Army.

The Serbians then advanced toward Albania,taking most of the region north of Vlora and into the AdriaticCoast, thereby achieving Serbia’s ambition of gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea. Montenegrin forces also occupied a section of northern Albania, and advanced to the fortified city of Shkoder, where they begana siege on October 28, 1912 that would last for several months.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background At thestart of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire was a spent force, a shadowof its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that had struckfear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vastterritories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the Europeanpowers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britainand Francesupported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order torestrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

In Europe, the Ottomans hadlost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central andcentral eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria,Montenegro, and Greecehad gained their independence. As aresult, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainlandwas Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace,to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by thenew Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians,Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into its sphereof influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to aSerbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when theBulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegrojoined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgariaand Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance,but Bulgaria saw the need tobring in Greece, inparticular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Seaand neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea,once fighting began. The Balkan Leaguebelieved that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the ItalianEmpire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; andsecond, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internallydivided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan Leagueand regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the RussianNavy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbiaalso had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovinain order to gain a maritime outlet through the AdriaticCoast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupiedOttoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed theregion in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and preparedfor war as well. By August 1912,increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.