Daniel Orr's Blog, page 39

January 5, 2022

January 5, 1992 – Bosnian War: Bosnian Serbs secede from Bosnia-Herzegovina

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs secededfrom Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also comprised a sizableminority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina bydeclaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formedalong ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslavconstituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretlyagreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majoritypopulation of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbiansand Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armedconflict between them. By this time,heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to openhostilities.

Mediators from Britainand Portugalmade a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincingBosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political powerin a decentralized government. Just tendays later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejectedthe agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

Background Bosnia-Herzegovinahas three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of thepopulation, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Sloveniaand Croatiadeclared their independences in June 1991. On October 15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence ofBosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session inprotest. Then acting on a request fromboth the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a EuropeanEconomic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11,1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since noreferendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs secededfrom Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also comprised a sizableminority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina bydeclaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formedalong ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslavconstituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretlyagreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majoritypopulation of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbiansand Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armedconflict between them. By this time,heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to openhostilities.

Mediators from Britainand Portugalmade a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincingBosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political powerin a decentralized government. Just tendays later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejectedthe agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

War At any rate,by March 1992, fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forcesattacked Bosniak villages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were themost powerful early in the war, as they were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had 150,000soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillery pieces,and several aircraft. Many Serbianmilitias also joined the Bosnian Serb regular forces.

Bosnian Croats, with the support of Croatia, had 150,000 soldiers and300 tanks. Bosniaks were at a greatdisadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’s war arsenal wasstockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by the Yugoslav Army(which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the early stages of thewar). A United Nations (UN) arms embargoon Yugoslaviawas devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weaponsfrom foreign sources.

In March and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serbforces launched large-scale operations in eastern and northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina. These offensives were so powerful that largesections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat territories were captured and came underBosnian Serb control. By the end of1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled 70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Then under a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army wasordered to leave Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did not affect seriously theBosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority of the Yugoslavsoldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldiers simply joinedthe ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting, using the sameweapons and ammunitions left over by the departing Yugoslav Army.

In mid-1992, a UN force arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina thatwas tasked to protect civilians and refugees and to provide humanitarianaid. Fighting between Bosniaks andBosnian Croats occurred in Herzegovina(the southern regions) and central Bosnia, mostly in areas whereBosnian Muslims formed a civilian majority. Bosnian Croat forces held the initiative, conducting offensives in NoviTravnik and Prozor. Intense artilleryshelling reduced Gornji Vakuf to rubble; surrounding Bosniak villages also weretaken, resulting in many civilian casualties.

In May 1992, the Lasva Valley came under attackfrom the Bosnian Croat forces who, for 11 months, subjected the region tointense artillery shelling and ground attacks that claimed the lives of 2,000mostly civilian casualties. The city of Mostar, divided intoMuslim and Croat sectors, was the scene of bitter fighting, heavy artillerybombardment, and widespread destruction that resulted in thousands of civiliandeaths. Numerous atrocities werecommitted in Mostar.

January 4, 2022

January 4, 1951 – Korean War: Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul

On December 31, 1950, Chineseand North Korean forces launched an attack on Seoul, breaking through South Korean andAmerican positions and threatening to encircle the whole UN defensive lines northand east of the city. On January 4,1951, UN forces, who were outnumbered 2:1 by the attackers, retreated from Seoul, which was capturedby the Chinese and North Koreans, and marked the third time the city changedhands during the war.

(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

War On June 25, 1950,after some initial fighting in the Ongjin area, North Korea launched a full-scaleinvasion across the 38th parallel. North Korean invasionforces, which consisted of 90,000 troops and supported by armored and artilleryunits, crossed into South Korea from east to west of the line. South Korean border defenses south of theline were easily overcome. South Koreanforces, lacking heavy artillery and powerful anti-tank weapons, surrendered ordefected en masse, or fled south. OnJune 28, 1950, Seoulfell, with President Rhee and his government having vacated the capital inadvance of the North Korean offensive. To forestall the North Koreans, the South Korean military destroyed themain bridge south of Seoul across the Han River, causing the deaths of hundreds of civilianswho were crossing the bridge at the time. Thousands of South Korean troops also were unable to leave the city and werelater captured by the North Koreans. Bythe third day of the invasion, South Korea was verging on collapse.

On June 25, 1950, the UnitedNations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 82 which called for an end tohostilities, and demanded that North Korean forces withdraw from South Korea. The resolution passed because at that time,the Soviet Union, which was a permanent UNSC member with veto power, hadboycotted the UNSC meetings in protest of the UN’s continued non-recognition ofChina. The Soviet government also challenged theUN’s legitimacy to decide on the Korean conflict, stating that the war was aninternal security issue, and that the 38th parallel was a militarydemarcation and not an international border.

Then on June 27, 1950, theUNSC passed Resolution 83, which called on UN member states to provide militaryassistance to South Koreato counter the North Korean invasion. Like South Korea, theUnited States was caughtoff-guard by the invasion, but quickly moved into action, and used its strongdiplomatic influence to mobilize international condemnation of North Korea. Up until now, President Truman viewed the Cold Waras relating only to Europe, and the U.S.containment policy as directed against the Soviet Union and its Eastern Bloc allies. But with the outbreak of the Korean War, forthe United States, the ColdWar had come upon Asia.

President Truman particularlylikened the North Korean invasion to Germany’saggression in World War II, and announced that his government would not repeatthe pre-war Allied appeasement policy, and that the United States would meet the NorthKorean “challenge” with force. And inview of this expanded Cold War policy, on June 27, 1950 (two days after thestart of the Korean War), President Truman ordered the U.S.7th Fleet to proceed to the Taiwan Strait, to prevent hostilities between theRepublic of China (Taiwan) and the People’s Republic of China. Both Chinese states pursued a policy todestroy its rival, but the arrival of the American naval fleet deterred thePeople’s Republic of Chinafrom launching its long-planned invasion of Taiwan.

At the start of the war, the U.S.military was undergoing a drastic reduction in combat strength because of majorcutbacks in military appropriations following World War II. Furthermore, because of the perceived greatersecurity threat in Europe, the United Statesconcentrated its forces there in line with its “Europe First” policy, leadingto the U.S. militaryscrambling to assemble enough American military units for Korea. During the early stages of the war, the United States experienced some difficultydispatching sufficient forces to the fighting, as U.S.units in Japanwere insufficiently trained for combat and seriously under-strength. As a result, only small advance unitsinitially were sent to the fighting in Korea.

Subsequently during the war,a combined total of some 370,000 foreign troops from 16 UN countries fought onthe side of South Korea. Of this number, nearly 90% was provided bythe United States (326,000 troops), while Britain(14,000), Canada (8,000),and Turkey(5,000) also sent sizable contingents.

On the day of the invasion,the U.S. governmentevacuated American civilians from South Korea. On June 27, 1950, with the passage of UNSCResolution 83 authorizing the use of force against the North Korean invasion, theU.S. military based in Japan sent warplanes into bombing raids in North Korea. U.S. planes attacked airfields anddestroyed several North Korean planes on the ground. U.S. ships also were rushed toKorean waters, where they shelled North Korean positions along the coast,somewhat slowing down the North Korean advance in these coastal areas.

On July 7, 1950, the UNSCpassed Resolution 85, which merged all UN member units into one unified force(called the United Nations Command, or UNC) under one commander. That same day, President Truman named GeneralDouglas MacArthur (head of the Far East Command based in Tokyo, Japan)as commander-in-chief of the UNC. TheEighth U.S. Army, headquartered in Japan, would serve as the mainAmerican force in the Korean War. Itscommander, General Walton Walker, was named as commander of the UNC groundforces. The South Korean government,whose army had been reduced to 22,000 troops from 90,000 since the start of thewar, allowed its remaining forces to be placed under the UNC.

On July 1, 1950, the first U.S. force, a 400-man battalion called TaskForce Smith (named after itscommander), arrived in Korea. Four days later, July 5, Task Force Smithencountered an armored North Korean column consisting of 5,000 troops that wasadvancing toward Osan. In the ensuingbattle, Task Force Smith caused some material damage to the enemy, destroying anumber of North Korean tanks, but itself was decimated and forced into achaotic retreat. But Task Force Smithachieved one objective: it delayed the North Korean advance to allow time for moreUN forces to arrive in the southern edge of the peninsula, where they couldestablish a stronger defensive line.

Meanwhile, other Americanunits that had arrived in Korea also used delaying tactics in clashes atPyeongtaek, Cheonan, Chochiwon, and Taejon, but were forced to retreat bynumerically superior North Korean forces that advanced using both frontalattacks and flanking tactics. At Taejon particularly, the U.S. 24th InfantryDivision was nearly destroyed and its commander, Major General William Dean,was captured by the North Koreans. Bythis time, South Korean and UN forces had been pushed to nearly the southernedge of the Korean Peninsula and faced thedanger of being annihilated or driven to the sea.

However, in early August1950, UN forces succeeded in establishing the Pusan Perimeter (Figure 16), a 140-mile long defensive line that partially followedthe length of the Naktong River. The Pusan Perimeter was so-named for Pusan, South Korea’smajor southern port, where U.S.and other UN forces, together with their war materials, were arriving in largenumbers daily.

In August 1950, North Koreanforces attacked many points along the Pusan Perimeter, and heavy fighting took place in Taegu,Masan, P’ohang-dong, and across the Naktong River. Because UN forces yet were numerically inadequate to defend the wholeline, General Walker used a “mobile defense” strategy, where his forces weremoved constantly to areas of enemy attack. North Korean forces broke through in many places, including a flankingmaneuver that threatened to drive straight to Pusan. But UN forces succeeded in establishing new defensive positions and thencounterattacked, driving back the North Koreans.

By early September 1950,North Korean forces were experiencing supply problems, as UN (mainly American)planes, which controlled the skies, were taking a heavy toll on North Koreanlogistical lines, attacking North Korean rail and road networks, weaponsdepots, oil refineries, and military facilities. As well, UN forces now had 180,000troops. By contrast, the North Koreaninvasion force, which had experienced heavy casualties, stood at some 100,000troops with the arrival of more reinforcements. UN forces also now had 600 tanks while North Korean armor, which hadspearheaded the invasion, had been reduced to fewer than 100 tanks from theoriginal 270 at the start of the war.

Figure 16. Some key areas during the KoreanWar.

January 3, 2022

January 3, 1961 – Cold War: The United States cut diplomatic ties with Cuba

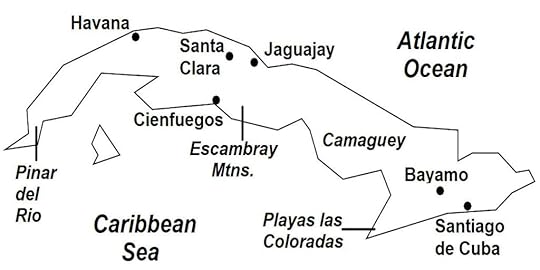

On January 3, 1961, the United States ended all official diplomaticrelations with Cuba, closedits embassy in Havana,and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions withthe island country. Earlier, in 1960, Castro had entered into a tradeagreement with the Soviet Union that includedpurchasing Russian oil. When U.S. petroleum companies in Cuba refused torefine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatorycounter-measures followed quickly. InJuly 1960, Cubaseized the American oil companies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports (which constituted90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’sbiggest source of revenue.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Background In March 1952, GeneralFulgencio Batista seized power in Cubathrough a coup d’état. He then canceledthe elections scheduled for June 1952, where he was running for the presidencybut trailed in the polls and faced likely defeat. Having gained power, General Batistaestablished a dictatorship, suppressed the opposition, and suspended theconstitution and many civil liberties. Then in the November 1954 general elections that were boycotted by thepolitical opposition, General Batista won the presidency and thus became Cuba’sofficial head of state.

President Batista favored a closeworking relationship with Cuba’swealthy elite, particularly with American businesses, which had an established,dominating presence in Cuba. Since the early twentieth century, the UnitedStates had maintained political, economic, and military control over Cuba; e.g.during the first few decades of the 1900s, U.S. forces often interveneddirectly in Cuba by quelling unrest and violence, and restoring politicalorder.

American corporations held a monopolyon the Cuban economy, dominating the production and commercial trade of theisland’s main export, sugar, as well as other agricultural products, the miningand petroleum industries, and public utilities. The United Statesnaturally entered into political, economic, and military alliances with andbacked the Cuban government; in the context of the Cold War, successive Cubangovernments after World War II were anti-communist and staunchly pro-American.

President Batista expanded thebusinesses of the American mafia in Cuba,where these criminal organizations built and operated racetracks, casinos,nightclubs, and hotels in Havanawith relaxed tax laws provided by the Cuban government. President Batista amassed a large personalfortune from these transactions, and Havanawas transformed into and became internationally known for its red-lightdistrict, where gambling, prostitution, and illegal drugs were rampant. President Batista’s regime was characterizedby widespread corruption, as public officials and the police benefitted frombribes from the American crime syndicates as well as from outright embezzlementof government funds.

Cuba didachieve consistently high economic growth under President Batista, but much ofthe wealth was concentrated in the upper class, and a great divide existedbetween the small, wealthy elite and the masses of the urban poor and landlesspeasants. (Cuban society also containeda relatively dynamic middle class that included doctors, lawyers, and manyother working professionals.)

President Batista was extremelyunpopular among the general population, because he had gained power throughforce and made unequal economic policies. As a result, Havana (Cuba’s capital) seethed withdiscontent, with street demonstrations, protests, and riots occurringfrequently. In response, PresidentBatista deployed security forces to suppress dissenting elements, particularlythose that advocated Marxist ideology. The government’s secret police regularly carried out extrajudicialexecutions and forced disappearances, as well as arbitrary arrests, detentions,and tortures. Some 20,000 persons werekilled or disappeared during the Batista regime.

In 1953, a young lawyer and formerstudent leader named Fidel Castro emerged to lead whatultimately would be the most serious challenge to President Batista. Castro previously had taken part in theaborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’sdictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civil disturbance (known as“Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies atthe University of Havana. Castro had run as an independent for Congressin the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was infuriated and began makingpreparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regimethat had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group,“The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

Revolution On July 26, 1953, FidelCastro led over 160 armed followers, which includedhis brother Raul, in an attack on the army garrisons in Santiago de Cuba and Bayamo, both located atthe southeast section of the island. Theplan called for seizing weapons from the garrisons’ armories and then armingthe local civilian population to incite a general uprising. The attack was foiled by the military,however, with the Castro brothers and many other rebels being captured,imprisoned, and subsequently charged for treason. Three months later, on October 16, the Castrobrothers were handed down long prison terms, together with their followers whowere given shorter prison sentences. Thetrials gained national attention, with Fidel Castro, who acted as his owndefense attorney, gaining wide public recognition. While serving time in prison, Fidel renamedhis organization the “26th of July Movement” or M-26-7 (Spanish: Movimiento 26 de Julio), in reference to the date of the failed attacks.

Then in March 1955, President Batista,who had been elected president a month earlier, believed that his regime wassecure and issued a general amnesty for jailed political enemies. Many political prisoners were freed,including the Castro brothers. Aftertheir release, the Castros, and in particular Fidel, were receivedenthusiastically by supporters. In June,however, a wave of violence broke out in Havana,and with the Cuban authorities moving to arrest political enemies, the Castrobrothers fled from Cuba andsettled in Mexico,which at that time was a haven for leftist elements.

In Mexico,Fidel Castro organized anti-Batista exilesinto an armed group as part of M-26-7, with funds solicited from wealthyémigrés belonging to the Cuban political opposition in the United States and Latin America. Just outside Mexico City, Fidel Castro’s group secretly began trainingfor rural guerilla warfare, which Fidel Castro planned to launch upon hisreturn to Cuba. The Castro brothers befriended Ernesto “Che”Guevara, an Argentine medical doctor and hard-line Marxist-Leninist, who joinedand then became one of the leaders of the M-26-7 organization.

By the autumn of 1956, Fidel Castro was ready to restart therevolution in Cuba. Early on the morning of November 25, 1956,he, Raul, Guevara, and 79 other rebels set off from Tuxpan on the Gulf ofMexico (Map 27) aboard the crudely refurbished yacht, Granma, for their 1,200 mile voyage to Cuba. The trip was scheduled to take five days, intime for Fidel Castro and his men to meet up with the M-26-7 rebels insoutheastern Cuba and then to jointly launch a coordinated attack againstcivilian and military targets in Oriente Province.

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba

However, thevoyage encountered many problems: the yacht’s engine broke down and had to berepaired, the boat’s hull sprung a leak and water had to bailed out by handwhile the pumps were repaired, a man fell overboard (but was located andrescued). Furthermore, the vessel had acapacity to hold only twelve persons, but was dangerously overloaded with over80 men, including weapons and supplies. On November 30, the scheduled day of the joint attack, Fidel and his menwere yet out at sea. The M-26-7 rebelsin Cuba launched theirattacks on several towns in Oriente Province, but governmentforces threw back the attackers after two days of fighting.

January 2, 2022

January 2, 1905 – Russo-Japanese War: Port Arthur falls to Japanese forces, ending a nine-month siege

By December 1904, the ever-wideningtrenches and tunnels which the Japanese were building soon threatened theRussian fortifications. The Japanesedetonated powerful explosives on the fortifications, bringing down the walls ofFort Chikuan(on December 18), Fort Erhlung (on December 28), and Fort Sungshu(on December 31). The Russian commandersof these garrisons were forced to surrender. On January 1, 1905, the Russian commander of Port Arthur offered to surrender, which was accepted bythe Japanese. Four days later, theJapanese Third Army entered Port Arthur. Thenine-month battle and siege of Port Arthur had cost the Japanese 58,000 casualties. But with its victory, the Japanese Army nowcontrolled the whole Liaodong Peninsula. Furthermore, the Japanese Third Army was nowfree to move north to join the continuing battle for southern Manchuria. Port Arthur’sfall demoralized the Russian Army in Manchuria,and shocked the Russian population.

(Taken from Russo-Japanese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

Background Bythe 19th century, Russia’sterritorial expansion into eastern Asia was encroaching into China, which was then ruled by theweakening Qing Dynasty. Russia and Chinasigned two treaties (the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and theConvention of Peking in 1860), where China ceded to Russia the territory known as OuterManchuria (present-day southern region of the Russian Far East). Then in 1896, by the terms of a constructionconcession, China allowed Russia to build the Chinese Eastern Railway, which would connect the eastern end of theTrans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok, through northernInner Manchuria (present-day Northeast China). In July 1897, construction work on this newrailway line began.

In December 1897, the RussianNavy started to use the port of Lushunkou, located at the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula. Four months later, in March 1898, Russia and Chinasigned an agreement, where the Chinese government granted a 25-year lease(called the “Convention for the Lease of the LiaotungPeninsula”) to Russia for Lushunkou and the surrounding areas,collectively called the Kwantung Leased Territory. The Russians soon renamed Lushunkou as Port Arthur, and developed it intoits main naval base in the Far East. Port Arthurwas operational all year long, compared to the other Russian naval base at Vladivostok, which was unusableduring winter. Both the Chinese EasternRailway and Kwantung Leased Territory allowed Russiato consolidate its hold over Inner Manchuria (although the region legallyremained part of China), which was furthered when Russia began constructing, in1899, the South Manchuria Railway to connect Harbinwith Port Arthur, via Mukden. Also by thelatter 19th century, Russiawas establishing firmer political and economic ties with the Korean Empire’sweak Joseon Dynasty.

Meanwhile, Japan (which had only recently industrializedand was emerging as a regional military power) also harbored ambitions insouthern Manchuria and Korea. For over two centuries (1633-1853), Japanhad implemented a near total isolationist policy from the outside world. But in the 1850s, Japanwas forced (under threat of military action) to sign treaties with the United Statesand European powers to establish diplomatic and trade relations. Seeing itself powerless against an attack bythe West, Japan reunifiedunder its emperor and then began a massive industrialization and modernizationprogram patterned after the West, which dramatically overturned and completelyaltered Japan’straditional feudal-based agricultural society. Within a period of one generation, Japan had become a modern,industrialized, and prosperous state, with the government placing particularemphasis on building up its military forces to the level matching those in theWest.

In the 1870s, Japan set its sights to emulating European-styleimperialist expansion (during this time, European powers were aggressivelyestablishing colonies in Asia and Africa), and turned to its old rival, Korea. Korea,although nominally sovereign and independent, was a tributary state of China. In September 1875, after failing to establishdiplomatic relations with Korea,Japan sent a warship to Korea. Using its artillery, the Japanese ship openedfire and devastated the coastal defenses of Ganghwa Island, Korea. Six months later, February 1876, Japan sentsix warships to Korea, forcing the Korean government to sign a treaty withJapan, the Gangwa Treaty, which among other provisions, established diplomaticrelations between the two countries, and forced Korea to open a number of portsto trade with Japan. Thereafter,European powers followed, opening diplomatic and trade ties with Korea, and ending the latter’s self-imposedisolationist policy (Koreauntil then had been known as the “Hermit Kingdom”).

But Japan was interested not only in opening tradewith Korea, but indominating the whole Korean Peninsula. Subsequently, Japanstarted to interfere in Korea’sinternal affairs. Before long, theKorean ruling elite became divided into two factions: the pro-Japanese faction,comprising progressives who wanted to modernize Korea in association withJapan; and the pro-Chinese faction, comprising the conservatives, including theruling Joseon monarchy, who were firmly anti-Japanese and wanted Korea’snational development under the tutelage of China or with the West.

The growing Japaneseinterference in Korea’saffairs made conflict between Japanand Chinainevitable. War finally broke out in theFirst Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), where Japanese forces triumpheddecisively. In the peace treaty (April1895) that ended the war, Chinarecognized Korea’sindependence, (until then, Koreawas a tributary state of China),China paid Japan an indemnity, and ceded to Japan theeastern part of the Liaodong Peninsula (as well as Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands). In the aftermath, Japanreplaced China as thedominant controlling power in Korea.

But immediately thereafter, Russia, which also had power ambitions insouthern Manchuria, particularly the vital Lushunkou (later Port Arthur), convinced Franceand Germany to join itscause and force Japan toreturn the Liaodong Peninsula to China,in exchange for China payingJapana larger indemnity. Japan reluctantly acquiesced,seeing that its forces were powerless to fight three European powers at thesame time.

Cash-strapped China sought financial assistance from Russia to pay its large indemnity to Japan. Russiareleased a loan to China,but also proposed a Sino-Russian alliance against Japan. In June 1896, Chinaand Russia signed the secretLi-Lobanov Treaty where Russiaagreed to intervene if Chinawas attacked by Japan. In exchange, Chinaallowed Russia the use ofChinese ports for the Russian Navy, as well as for Russiato build a railway line across North East China (the Chinese Eastern Railway) to Vladivostok. As the treaty also permitted the presence ofRussian troops in the region, Russiasoon gained full control of northeast China. Then after signing the lease for the Liaodong Peninsula, particularly vital Port Arthur, Russiagained control of southern Manchuria as well.

Meanwhile, in Korea,anti-Japanese sentiment intensified further when in October 1895, Queen Min,wife of King Gojong, was assassinated, with most Koreans blaming the Japanese,because of the queen’s strong anti-Japanese stance. Fearing for his life, Korean King Gojong fledto the Russian diplomatic office. WithRussian protection, in October 1897, King Gojong proclaimed the Korean Empire,an act to symbolize the end of China’sdomination of his country. Koreans werestrongly anti-imperialistic and desired self-rule. Most Koreans also wanted to establishstronger ties with European countries and the United States to stop what they believed were Japan’s ambitions to take overtheir nation.

Undeterred, in November 1901,Japan approached Russia with a proposal: in exchange for Japan recognizing Manchuria as falling withinthe Russian sphere of control and influence, Russiawould recognize Japan’scontrol over Korea. As early as June 1896, Japan and Russiahad agreed to form a joint protectorate over Korea, which would serve as abuffer zone between them. But in April1898, in another treaty, Russiaacknowledged Japan’scommercial and economic interests in Korea

In January 1902, Japan andBritain signed a military pact (the Anglo-Japanese Alliance), where the British promised to intervene militarily for Japan in the event that in a Russo-Japanese war,a third party entered the war on Russia’sside against Japan. The British motive in the treaty was to curb Russia’s territorial expansionism in East Asia;for Japan, the alliancestrengthened its resolve to go to war with Russia.

Subsequently, Russia appeared to be willing to compromise withJapan, even indicating itsintention to withdraw from Manchuria. In March 1902, Russiaand France signed a militarypact, but the French government stated that it would intervene for Russia (if the latter went to war) only in a warin Europe and not in Asia. As a result, Russiawould have to fight alone in a war with Japan.

A faction in the Russiangovernment, led by the Foreign Ministry, wanted a peaceful settlement with Japan. However, Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian monarch, and the Russianmilitary high command, pressed for continued Russian expansionism in the FarEast, being confident that the Russian military, with a long history of wars inEurope, could easily defeat upstart Japan. Then when Russiadid not withdraw from Manchuria, in July 1903, the Japanese envoy in St. Petersburg (Russia’s capital) issued a diplomaticprotest. But in August 1903, Japan again offered Russiathe proposal that in exchange for Russia’srecognition of Japan’scontrol of Korea, Japan would accept Russia’scontrol of Manchuria. In October 1903, Russiamade a counter-proposal with the following stipulations: that Manchuria fellunder Russia’s sphere ofinfluence; that Russiarecognized Japan’scommercial interests in Korea;and that all territory north of the 39th parallel in the Korean Peninsulawould be a demilitarized buffer zone where no Russian or Japanese forces coulddeploy.

Each side’s proposals wereunacceptable to the other, but the two sides agreed to hold talks. By January 1904, with no progress being madein the talks, Japanese representatives concluded that the Russians werestalling. Again, Japan repeated its August 1903 offer, but afterreceiving no reply, on February 6, 1904, Japancut diplomatic ties with Russia. Two days later, Japandeclared war on Russia.

January 1, 2022

January 1, 1959 – Cuban Revolution: President Fulgencio Batista flees into exile

When reports of the fall of Santa Clara reached Havana,President Fulgencio Batista decided to step down from office, and prepared toleave immediately. A few weeks earlier,in early December, his government had received a major diplomatic setback whenthe United States ceasedrecognition of his presidency and urged him to step down as Cuba’s leader. In the early hours of January 1, 1959,Batista and a large entourage of his closest supporters, left Havanafor exile in the nearby Dominican Republic. He brought with him a vast amount of money, estimated at $300million. Batista eventually settled in Portugal,where he was granted political asylum.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 2)

Aftermath In Havana, President Urrutia, and especially CheGuevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and the M-26-7 fighters, took control of civilianand military institutions of the government. Similarly in Oriente Province, Fidel Castro established authority overthe regional governmental and military functions. In the following days, other regionalmilitary units all across Cubasurrendered their jurisdictions to rebel forces that arrived. Then from Santiago de Cuba, Fidel Castro began a nearly week-long journey to Havana, stopping at everytown and city to large crowds and giving speeches, interviews, and pressconferences. On January 8, 1959, hearrived in Havanaand declared himself the “Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of thePresidency”, that is, he was effectively head of the Cuban Armed Forces underthe government of President Urrutia and newly installed Prime Minister JoseMiro. Real power, however, remained withCastro.

In the next few months, the Castroregime consolidated power by executing or jailing hundreds of Batistasupporters for “war crimes” and relegating to the sidelines the other rebelgroups that had taken part in the revolution. During the war, Fidel Castro had promised the return of democracy byinstituting multi-party politics and holding free elections. Now however, he spurned these promises,declaring that the electoral process was socially regressive and benefited onlythe wealthy elite.

Castro denied being a communist, themost widely publicized declaration being during his personal visit to the United Statesin April 1959, or four months after he gained power. Members of the Popular Socialist Party, orPSP (Cuban communists), however, soon began to dominate key governmentpositions, and Cuba’s foreign policy moved toward establishing diplomaticrelations with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries. (By 1961 when Castro had declared Cuba acommunist state, his M-26-7 Movement had formed an alliance with the PSP, the13th of March Movement – DR, and other leftist organizations; thiscoalition ultimately gave rise to the Cuban Communist Party.)

President Urrutia, who was a politicalmoderate and a non-communist, made known his concern about the socialistdirection of the government, which put him directly in Castro’s way. Consequently in July 1959, President Urrutiawas forced to resign from office, as Prime Minister Miro had done earlier inFebruary. A Cuban communist took over asthe new president, subservient to the dictates of Fidel Castro. Castro had become the “Maximum Leader”(Spanish: Maximo Lider), or absolutedictator; he abolished Congress, ruled by decree, and suppressed all forms ofopposition. Free speech was silenced, aswere the print and broadcast media, which were placed under governmentcontrol. In the villages, towns, andcities across Cuba,neighborhood watches called the “Committees for the Defense of the Revolution”were formed to monitor the activities of all residents within theirjurisdictions and to weed out dissidents, enemies, and“counter-revolutionaries”. In 1959, landreform was implemented in Cuba;private and corporate lands were seized, partitioned, and distributed topeasants and landless farmers.

On January 7, 1959, just a few daysafter the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the newCuban government under President Urrutia. But as Castro later gained absolutepower and his government gradually turned socialist, relations between the twocountries deteriorated rapidly. By July1959, just seven months later, U.S.president Dwight Eisenhower was planning Castro’s overthrow; subsequently inMarch 1960, he ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize andtrain U.S.-based Cuban exiles for an invasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro entered into a tradeagreement with the Soviet Union that includedpurchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S. petroleum companies in Cuba refused to refine the importedRussian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatory counter-measures followedquickly. In July 1960, Cuba seized the American oilcompanies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United Statesimposed an economic embargo on Cubaand banned all imports (which constituted 90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’sbiggest source of revenue. In January1960, the United Statesended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba,closed its embassy in Havana,and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions withthe island country.

With Cubashedding off democracy and taking on a clearly communist state policy,thousands of Cubans from the upper and middle classes, including politicians,top government officials, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many otherprofessionals fled the country for exile in other countries, particularly inthe United States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans choseto remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start a counter-revolutionin the Escambray Mountains;these rebel groups’ activities laid the groundwork for Cuba’s next internal conflict, the“War against the Bandits”.

December 30, 2021

December 30, 1958 – Cuban Revolution: Rebels capture Jaguajay

By early December 1958, Fidel Castrohad gained control over much of the countryside of Oriente and Las VillasProvince, and was ready to launch major attacks in order to seize the wholeeastern half the island. Che Guevara’sfinal offensive in Las Villas involved close coordination with Cienfuegos’column by first attacking the surrounding towns in order to isolate SantaClara. On December 14 and 17,respectively, Guevara’s forces captured the towns of Fomento and Remedios. In the town of Jaguajay,however, the small army garrison put up a fierce resistance that repulsedsuccessive attacks by Cienfuegos’ force. On December 30, after 11 days of fighting, the Jaguajay defenders ranout of ammunition and surrendered. With Jaguajay’s fall and the voluntarycapitulation of the military garrisons at Caibarien and Cienfuegos three daysearlier, Che Guevara proceeded unopposed to Santa Clara.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Aftermath In Havana, President Urrutia,and especially Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and the M-26-7 fighters, tookcontrol of civilian and military institutions of the government. Similarly in Oriente Province, Fidel Castro established authority overthe regional governmental and military functions. In the following days, other regionalmilitary units all across Cuba surrendered their jurisdictions to rebel forcesthat arrived. Then from Santiago de Cuba,Fidel Castro began a nearly week-long journey to Havana, stopping at every townand city to large crowds and giving speeches, interviews, and pressconferences. On January 8, 1959, hearrived in Havana and declared himself the “Representative of the Rebel ArmedForces of the Presidency”, that is, he was effectively head of the Cuban ArmedForces under the government of President Urrutia and newly installed PrimeMinister Jose Miro. Real power, however,remained with Castro.

In the next few months, the Castroregime consolidated power by executing or jailing hundreds of Batistasupporters for “war crimes” and relegating to the sidelines the other rebelgroups that had taken part in the revolution. During the war, Fidel Castro had promised the return of democracy byinstituting multi-party politics and holding free elections. Now however, he spurned these promises,declaring that the electoral process was socially regressive and benefited onlythe wealthy elite.

Castro denied being a communist, themost widely publicized declaration being during his personal visit to the UnitedStates in April 1959, or four months after he gained power. Members of the Popular Socialist Party, orPSP (Cuban communists), however, soon began to dominate key governmentpositions, and Cuba’s foreign policy moved toward establishing diplomaticrelations with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries. (By 1961 when Castro had declared Cuba acommunist state, his M-26-7 Movement had formed an alliance with the PSP, the13th of March Movement – DR, and other leftist organizations; thiscoalition ultimately gave rise to the Cuban Communist Party.)

President Urrutia, who was a politicalmoderate and a non-communist, made known his concern about the socialist directionof the government, which put him directly in Castro’s way. Consequently in July 1959, President Urrutiawas forced to resign from office, as Prime Minister Miro had done earlier inFebruary. A Cuban communist took over asthe new president, subservient to the dictates of Fidel Castro. Castro had become the “Maximum Leader”(Spanish: Maximo Lider), or absolutedictator; he abolished Congress, ruled by decree, and suppressed all forms ofopposition. Free speech was silenced, aswere the print and broadcast media, which were placed under governmentcontrol. In the villages, towns, andcities across Cuba, neighborhood watches called the “Committees for the Defenseof the Revolution” were formed to monitor the activities of all residentswithin their jurisdictions and to weed out dissidents, enemies, and“counter-revolutionaries”. In 1959, landreform was implemented in Cuba; private and corporate lands were seized,partitioned, and distributed to peasants and landless farmers.

On January 7, 1959, just a few daysafter the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the new Cubangovernment under President Urrutia. But as Castro later gained absolute powerand his government gradually turned socialist, relations between the twocountries deteriorated rapidly. By July1959, just seven months later, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower was planningCastro’s overthrow; subsequently in March 1960, he ordered the CentralIntelligence Agency (CIA) to organize and train U.S.-based Cuban exiles for aninvasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro entered into a tradeagreement with the Soviet Union that included purchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S. petroleum companies in Cubarefused to refine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures andretaliatory counter-measures followed quickly. In July 1960, Cuba seized the American oil companies and nationalizedthem the next month. In October 1960,the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports(which constituted 90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’sbiggest source of revenue. In January1960, the United States ended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba,closed its embassy in Havana, and banned trade to and forbid American privateand business transactions with the island country.

With Cuba shedding off democracy andtaking on a clearly communist state policy, thousands of Cubans from the upperand middle classes, including politicians, top government officials,businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many other professionals fled the countryfor exile in other countries, particularly in the United States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans choseto remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start acounter-revolution in the Escambray Mountains; these rebel groups’ activitieslaid the groundwork for Cuba’s next internal conflict, the “War against theBandits”.

December 29, 2021

December 29, 1996 – Guatemalan Civil War: The Guatemalan government and URNG rebels sign a peace treaty ending the 36-year civil war

In January 1994, the government and URNG (Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity;Spanish: UnidadRevolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca) restarted peace talks underthe sponsorship of the UN and Organization of American States (OAS). A number of agreements in 1996 were reachedthat finally brought the war’s end: a ceasefire was signed in March 20; URNGwas legalized on December 18; and a final peace treaty, called the “Accord fora Firm and Lasting Peace”, was signed on December 29. The 36-year war, the longest and bloodiest inCentral America, finally was over.

(Taken from Guatemalan Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Background of theGuatemalan Civil War In 1821, Guatemalagained its independence from Spainas part of the (First) Mexican Empire. Then when the Empire collapsed two year later, Guatemala became a memberof the United Provinces of Central America (together with El Salvador,Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica), which also fell apart in 1838. Thereafter, Guatemala became a separate, fullysovereign state.

Political power in fully independent Guatemala wascontrolled by the ladinos (hispanized descendants of Amerindian-Europeanunions) and the small pure SpanishCriollos, who passed laws and policies that were advantageous to them, andcoincidentally alienated the indigenous Amerindian population (which comprisedabout 40% of the population).

Central America

Central AmericaWealth distribution was uneven, with the biggest landownersowning vast tracts of lands, called latifundia, which were developed intocoffee and sugarcane plantations and worked by the indigenous farm hands underharsh, exploitative conditions. About 2%of the population owned 70 – 80% of all agricultural lands, while 90% of theindigenous people owned plots of land that were too small to subsist on.

This socio-economic imbalance was enhanced further when in1904, President Manuel José Estrada allowed the U.S. firm, United Fruit Company(UFC), to establish banana farm operations in the country. With generous tax incentives and severalthousands of hectares allocated by the government, UFC opened large bananaplantations in regions near the Atlantic side of the country. As part of the agreement, UFC developed andcontrolled the road, railway, and port infrastructures to enhance regionaldevelopment and support its own commercial operations.

Thereafter, succeeding Guatemalan governments maintainedclose ties with the United States, and allowed UFC to expandconsiderably. By the 1940s, the Americanfirm’s massive investments and economic benefits had become crucial to thelocal economy that Guatemalaand the United Statesentered into economic and military agreements. Particularly favorable to the United States in the 1940s was the regime of President JorgeUbico, who allowed the U.S.government to establish military bases in Guatemala. He also allocated many more thousands ofhectares of land and granted additional financial incentives that allowed UFCto expand further.

In July 1944, President Ubico was forced out of office, anda brief period of political unrest followed that led to the “OctoberRevolution”, an uprising on October 19, 1944, by reformist army officers thatoverthrew the military government that had succeeded into office. Then in the presidential election held inDecember 1944, Juan José Arévalo prevailed, and thereafter embarked on adramatic effort to radically change the country’s socio-economic system. President Arévalo enacted labor lawsbeneficial to workers, electoral reforms that allowed greater voterparticipation, and educational programs to reach a larger segment of thepopulation.

In 1951, Jacobo Arbenz succeeded as president after winningthe presidential race in free, fair elections. President Arbenz continued the social reforms of his predecessor, butmade two crucial additions: he legalized the Guatemalan Party of Labor (PGT;Spanish: Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo), which was the local communistparty; and implemented an agrarian reform law. Regarding the second point, President Arbenz wanted to nationalize about600,000 hectares of land, which would be carried out by purchasing unusedagricultural lands from big landowners (including UFC), and then divide thelands and distribute the resulting parcels to peasants. The combined tenures of Presidents Arévaloand Arbenz, who implemented socially and economically progressive reforms,historically have been called the “Ten Years of Spring”.

The reforms were strongly condemned by the traditionalpolitical elite, business and landowning classes, Catholic Church, and themilitary, as they threatened to overturn the established order. UFC also particularly was alarmed, and turnedto the U.S.government for assistance.

By the early 1950s, the Cold War was in full swing, and the United States,through its intelligence agencies, led by the Central Intelligence Agency(CIA), was watching out for countries around the world where communismpotentially could take hold. UFCpublicly denounced President Arbenz, calling him a communist who had ties withthe Soviet Union. Businessmen and landowners, and the CatholicChurch launched similar media and propaganda campaigns, and organized streetprotests against what they perceived was a communist government. The United States stopped sending military aid to Guatemala, and increased weapons deliveries tonearby Honduras and El Salvador,both ruled by pro-U.S. regimes.

Facing the threat of aggression by its neighbors and the United States, the Guatemalan governmentpurchased weapons from Czechoslovakia,a Soviet satellite state, which further raised U.S.suspicions that Guatemalamight allow a “Soviet beachhead” in the Western Hemisphere. In June 1954, a CIA-organized force ofGuatemalan mercenaries invaded Guatemala. The Guatemalan military foiled the attack,but President Arbenz, concerned that U.S. forces would intervenedirectly, abdicated and fled into exile abroad.

After a brief period of political restructuring that saw asuccession of military rulers take charge of government, Colonel CarlosCastillo Armas, the coup leader, came to power and then set about to reversethe reforms of the previous governments. The agrarian reform law was scrapped and expropriated lands werereturned to the landowners. The PGT wasoutlawed, and leftists and communists were targeted by the military, sparking awave of killings and assassinations against leaders of peasant and laborunions. The 1954 coup ended the “TenYears of Spring” and led to the country being ruled by a succession of militaryrulers (including one civilian government that was subservient to the military)for the next 32 years.

December 28, 2021

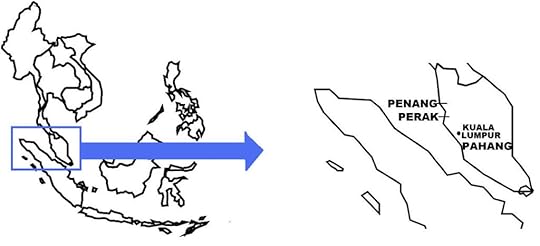

December 28, 1956 – Malayan Emergency: Chin Peng and Chief Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman meet in Baling, Malaya

By 1955, the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) was onthe decline, its combat strength weakened by combat deaths, desertions, andsurrenders, morale was low, and its popular support was greatly reduced. In September 1955, some three months afterhis party won the general elections, Tunku Abdul Rahman, chief Minister ofMalaya, offered amnesty to the MNLA. Government representatives and the CPM leadership held negotiations inOctober and November 1955, paving the way for the Baling Peace Talks (held inBaling, in present-day northern Peninsular Malaysia) in December 1955, whereCPM leader Chin Peng met with Chief Minister Tunku. However, this meeting produced nosettlement. Subsequent offers by ChinPeng to continue negotiations were spurned by Tunku, who insisted onunconditional surrender, i.e. that the MNLA must disarm and disband, and theCPM would not be granted official recognition. In February 1956, Tunku rescinded the amnesty offer.

(Taken from Malayan Emergency – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

On June 12, 1948, three European plantation managers werekilled by armed bands, forcing British authorities to declare a state ofemergency throughout Malaya, which essentiallywas a declaration of war on the CPM. TheBritish called the conflict, which lasted 12 years (1948-1960), an “emergency”so that business establishments that suffered material losses as a result ofthe fighting, could make insurance claims, which the same would be refused byinsurance companies if Malaya were placed under a state of war.

The state of emergency, which was applied first to PerakState (where the murders of the three plantation managers occurred) and thenthroughout Malaya in July 1948, gave the police authorization to arrest andhold anyone, without the need for the judicial process. In this way, hundreds of CPM cadres werearrested and jailed, and the party itself was outlawed in July 1948. The murders of the three plantation managersare disputed: British authorities blamed the CPM, while Chin Peng denied CPM involvement,arguing that the CPM itself was caught by surprise by the events and wasunprepared for war, and that he himself barely avoided arrest in the intensivegovernment crackdown that followed the killings.

The CPM retreated into the Malayan jungles where itreconstituted its military wing under a new name, first the Malayan Peoples’Anti-British Army (MPABA), and then in February 1949 as the Malayan NationalLiberation Army (MNLA). Combat unitswere hastily re-formed (from the wartime MPAJA units) and buried weapons cacheswere recovered from the ground. The MNLAcombat strategy consisted of acquiring more weapons by raiding police stationsand ambushing army and security patrols. The guerillas also attacked civilian and public infrastructures to upsetthe Malayan economy, thereby undermining the British government. Tin mine operations were disrupted, rubberplantations destroyed, and operations managers targeted forassassinations. As well, buses wereransacked, railway trains upturned, and public utilities sabotaged. These indiscriminate attacks soon were havinga detrimental effect on the local workers and ordinary people, which forced theMNLA to end this strategy.

The MNLA obtained its support mainly from the ethnic Chinesepopulation, which provided the rebels with recruits, food, supplies, andinformation. MNLA support particularlywas strong among the so-called “squatter” population, the 600,000 people wholived in remote areas which typically were beyond the reach of Britishadministrative and police control. Direct auxiliary support to the rebels was provided by ordinarycivilians using the clandestine “Min Yuen” (Masses Movement) network. “Min Yuen” functioned in many ways, includingbeing a link between the MNLA and the general population, providing the MNLAwith logistical support, and being a courier and communications system across Malaya, where messages (written in small slips of paper)were passed to and from the various rebel commands. For about three years from the start of theEmergency (1948-1951), the communist rebels held the initiative againstgovernment forces; at its peak, the MNLA launched over 6,000 armed incidents in1951.

At the start of the war, the undermanned British forces in Malaya were unable to confront the rapidly expandingcommunist insurgency. Consequently,British military and police units were brought in from outside of Malaya, while local recruitment to the Malayan policeforce and privately-organized militias (by plantation and mine owners)increased government and anti-insurgency security strength to over 250,000personnel by the early 1950s. Furthermore, the arrival of army contingents from Australia, New Zealand and Fiji, as well as Gurkha troops inthe British Army and security forces from British East African territories,soon allowed the British to seize the initiative from the communist rebels by1952.

Initially, the British sent large military formations to“search and destroy” operations against MNLA camps which were located deep inthe Malayan mountains. British warplanesalso launched thousands of bombing and strafing sorties. By 1950, these large-scale offensives,cumbersome and ineffective against a concealed enemy, were abandoned. Small-unit operations were adopted, whichwere better suited to the Malayan jungles. The British also saw that their air attack missions achieved only modestsuccess, because of the dense forest cover, the absence of reliable maps, andthe difficult high-altitude weather conditions.

Maneuverability of British Army ground units also washandicapped by the jungle terrain and the elements, and the difficulty inlocating the enemy. British soldiersalso were unable to distinguish between friend and foe, and therefore regardedall persons in remote settlements as potentially hostile. As a result of these difficulties, theBritish committed a number of atrocities on the local population, the mostnotable being the Batang Kali Massacre in December 1948, where 24 villagerswere killed and their houses burned.

The British also built fortified camps deep in the junglesin areas that were inhabited by the indigenous Orang Asli tribal population,who previously had supported the MNLA, but were won over by the British. From these jungle camps, the British sent outpatrols to seek out and engage the rebels. Members of the Orang Asli also were organized into local militias todefend their villages.

Early on in the war, the British saw that warfare alonecould not win the war, because of the difficulty of penetrating the thickMalayan jungles and the refusal of the enemy to engage in open combat. They therefore implemented a number ofnon-military approaches to confront the insurgency. Shortly after the state of emergency wasdeclared, the British jailed hundreds of ethnic Malay communists in order tokeep the insurgency from spreading to other Malays (as well as ethnic Indians), thereby reinforcing theperception that the MNLA was a mainly ethnic Chinese organization. For the same reason, in Pahang State where anethnic Malay-led MNLA unit operated, British authorities expelled the Malayrebels and brought the region under their control.

Still unable to defeat the MNLA, the British turned tostarving it into submission. The 600,000rural squatters from whom the rebels derived much of their support wereuprooted from their homes and moved to “New Villages”, which were guardedsettlement camps where British authorities provided the new residents withbasic necessities and public utilities, but also enforced strict restrictionson the residents’ personal movement, food allocations, and other civilrights. A curfew was imposed andviolators were subjected to severe punishment. By the mid-1950s, some 450 “New Villages” had been built. To win over the local population, the Britishlaunched a “hearts and minds” campaign, where the “New Villages” were providedwith educational and health care services, and primary utilities such aselectricity and clean water.

British authorities also co-opted the large anti-communistethnic Chinese population, forging friendly ties with the Malayan ChineseAssociation (MCA), which had been organized by moderate Chinese who sought toadvance Malayan Chinese interests through peaceful, democratic means. Intelligence gathering operations also weregreatly expanded during the Emergency, with emphasis placed on recruitingMalays, Chinese and Indians as intelligence operatives with the task of gaininginformation on the CPM’s organizational structure and courier andcommunications network. Working throughdeep cover agents, captured or surrendered rebels, seized CMP documents, andother sources, the government gained a large body of information on theCMP. British authorities alsoinfiltrated the rebels’ courier and communications system, and thus succeededin subverting MNLA and CPM operations.

The British also used psychological warfare, which were soeffective in demoralizing the ranks of the MNLA. Propaganda leaflets were air-dropped in themountains and jungles, anti-communist rallies were organized in towns andcities, and uncovered rebel weapons caches were left in place but sabotaged,for example, with self-exploding bullets and grenades.

Furthermore, the herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T were firstused during the Malayan Emergency, with British planes spraying them todefoliate the forests and deprive the rebels of cover. Also targeted were the insurgents’ own cropfields located in jungle clearings, as well as the roadsides where the Britishwere most vulnerable to rebel attack. Amixture of these two herbicides (called Agent Orange) was used extensively by U.S.forces during the Vietnam War.

The government’s multi-faceted approach to meet the MalayanEmergency was raised to a higher degree during the term of Gerald Templer asBritish High Commissioner in Malaya. Templer had been given broad powers by theBritish government following his predecessor’s assassination by MNLA guerillasin October 1951. Templer’s two-yeartenure (1952-1954) did much to turn the tide of the war in favor of theBritish, even though upon his departure, the MNLA continued to be athreat. Of all the counter-insurgencymethods that the British employed, the most successful was preparing Malaya for independence, a process that was acceleratedunder Templer’s tenure. The Britishreasoned that handing Malaya its independencewould nullify the CMP’s reason for existence, which was to end colonial rule.

As it turned out, however, Malaya’s road to independenceinvolved a long, tedious process, primarily because Malaya’s three main racialgroups (Malays, Chinese, and Indians) were not integrated and even mutuallyhostile to each other; this difficulty initially convinced the British that Malaya’s independence was virtually impossible toachieve.

Earlier in April 1946, the British organized the Malayanstates into a single polity, the Malayan Union, where the powers of the Sultanswere restricted, and the Chinese and Indians were to be grantedcitizenship. However, Malay nationalistsled a series of protests against granting citizenship to non-Malays. The British relented, and negotiations thatfollowed led to a compromise – the Malayan Union was abolished and replaced inFebruary 1948 with the Federation of Malaya. In the new polity, the Malayan sultans’ powers were restored; in exchange,ethnic Chinese and Indians were granted citizenship, and equality of all raceswas guaranteed. Furthermore, a Malaysultan would be the head of state, sovereignty over Malayawould rest with Malays, and Malay would be the official language. Conversely, the Chinese and Indians would beguaranteed representation at all levels of government and legislation, andtheir economic interests and social, cultural, and religious traditions wouldbe protected.

In 1954, Malayan interracial integration was bolstered withthe formation of the Alliance Party, a coalition of political partiescomprising the three leading ethnic-based political parties, i.e. United MalaysNational Organisation (UMNO), Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), and MalayanIndian Congress (MIC). Then in generalelections held in July 1955, the Alliance Party won decisively. Two years later (on August 31, 1957), theFederation of Malaya became a fully sovereign, independent state These political developments denigrated thelegitimacy of the CPM’s armed struggle, particularly since the 1955 electionand Malaya’s independence received overwhelming support from the generalpopulation.

By 1955, the MNLA was on the decline, its combat strengthweakened by combat deaths, desertions, and surrenders, morale was low, and itspopular support was greatly reduced. InSeptember 1955, some three months after his party won the general elections,Tunku Abdul Rahman, chief Minister of Malaya, offered amnesty to the MNLA. Government representatives and the CPMleadership held negotiations in October and November 1955, paving the way forthe Baling Peace Talks (held in Baling, in present-day northern PeninsularMalaysia) in December 1955, where CPM leader Chin Peng met with Chief MinisterTunku. However, this meeting produced nosettlement. Subsequent offers by ChinPeng to continue negotiations were spurned by Tunku, who insisted onunconditional surrender, i.e. that the MNLA must disarm and disband, and theCPM would not be granted official recognition. In February 1956, Tunku rescinded the amnesty offer.

December 27, 2021

December 27, 1949 – Indonesian War of Independence: The Netherlands officially recognizes Indonesia’s independence

On December 27, 1949, the Netherlands formally relinquished authority overthe United States of Indonesia (USI), which became a fully sovereign,independent state as the Republic of Indonesia. Indonesia’sindependence war caused some 50,000-100,000 Indonesian deaths. The Dutch military lost over 5,000 soldierskilled. Some 1,200 British soldiers(mainly British Indians) also were killed in action. Several million people were displaced. Also in the 1950s, a diaspora of took place,with some 300,000 Dutch nationals leaving Indonesiafor the Netherlands.

(Taken from Indonesian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

AftermathFrom the outset, USI was confronted with many problems. Just one month after its independence,Westerling, the Dutch officer known for his brutality in South Sulawesi, led aforce consisting of Dutch and anti-Republic fighters that attacked Bandung and Jakarta,which failed to overthrow Sukarno’sgovernment. In the aftermath, Westeringfled from Indonesia, whileIndonesian collaborators in the plot, which included the Sultan of Pontianakwho also headed the West Kalimantan State,were arrested and imprisoned. The coupattempt heightened the already widespread perception that USI was a Dutch machination. In the following months and with pressureexerted by President Sukarno, the federalstructure disintegrated, with USI states dissolving and subsuming under theauthority of the Indonesian Republic. On August 17, 1950, USI’s disintegration wascomplete, and Sukarno declared Indonesia a unitary state. Then in 1956, Sukarno dissolved the Netherlands-Indonesian Union,mainly because of the stalled talks regarding the future of West New Guinea.

In April 1950 in South Maluku wherepro-Dutch sentiment remained high, Indonesian militias from the former colonialarmy launched a rebellion and established the Republicof South Maluku in Ambon. Indonesian forces went on the offensive inthe islands, quelling the revolt by November 1950. In 1956-1957, rebellions led by military andcivilian leaders were launched in Sumatra and North Sulawesi, and insurgentgovernments were formed there that threatened Indonesia’s integrity. However, government offensives in March-June1958 pacified these regions, with the last insurgent groups surrendering by1961. Also in the first half of the 1960s, the government finally brought thedecade-long Darul Islam rebellion in West Java, as well as in South Sulawesi and Aceh, to an end.

World War II and the independence waralso had taken their toll on Indonesia’seconomy: infrastructures were destroyed, agriculture and industries wereruined, poverty was widespread, inflation soared, and the new governmentstruggled to provide basic public services. The country’s archipelagic nature and the hundreds of ethnic groups alsofostered disunity because of differences in languages, customs, traditions,religions, and ideologies. Domination bypolitically dominant Java particularly was a source of mistrust among the otherethnic groups. The national governmentalso was divided by dissent because of rival ideologies of the various leadingpolitical parties: communists under the Indonesian Communist Party,nationalists under Sukarno’s IndonesianNational Party, and Islamists under Nahdlatul Ulama and the Masyumi Party. Between 1945 and 1958, the Indonesiangovernment experienced 17 Cabinet changes.

By the second half of the 1950s,President Sukarno made steps to dissolve the country’sparliamentary system. In February 1957,he implemented “Guided Democracy”, where national policies would be decidedthrough consensus among the various political parties under the guidance of thepresident. In July 1959, he replaced theUSI-era constitution with the 1945 Constitution which provided for strongpresidential powers. Then in March 1960,he dissolved parliament and installed a rubber-stamp legislature in itsplace. Sukarno soon gained broad powers, causing a split inrelations with the Islamic parties, which were soon banned, and closer tieswith the communist PKI and the Indonesian military, both of which supportedGuided Democracy. At this time also, Indonesia experienced worsening relations withthe United States and otherwestern countries, and improving ties with the Soviet Union and other communist countries.

Meanwhile during the 1950s,Indonesian-Dutch relations continued to deteriorate because of the unresolvedissue of West New Guinea. In reprisal for the stalled talks, inDecember 1957, the Indonesian government nationalized some 250 Dutchcorporations in Indonesiaand expelled 40,000 Dutch nationals. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were cut in 1960. While continuing diplomatic pressure to gainWest New Guinea, Indonesiaalso launched infiltration attacks on the territory, which were repulsed by theDutch Army. However, by 1962, the Dutchgovernment had acquiesced and turned over West New Guinea’sauthority to the United Nations under UNTEA (United Nations Temporary ExecutiveAuthority). In May 1963, UNTEA handedauthority of the region to Indonesiawith the provision that a plebiscite would be held to determine the politicalaspirations of West Papuans.

In July-August 1969, a referendum washeld involving 1,000 tribal leaders (but not the 800,000 Papuans of theterritory), who voted unanimously to join Indonesia. Thereafter, the Indonesian government[1]declared West New Guinea as its 26th province, ending the 350 yearsof Dutch presence in the Dutch East Indies.

[1] By this time, Sukarno had fallen from powerfollowing a period of decline in popular support resulting from the armedconflict with Malaysia in 1963-1966 and the failed coup of the “30 SeptemberMovement” in October 1965. Sukarno’s decline coincided with the rise of General Suharto, who succeededas president in March 1967.

December 26, 2021

December 26, 1972 – Vietnam War: U.S. planes bomb Hanoi

On December 14, 1972, the U.S.government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return tonegotiations. On the same day, U.S.planes air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealingoff the coast to sea traffic. Then onPresident Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, onDecember 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under OperationLinebacker II, launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam,including Hanoi and Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, navalbases, and other military facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots,and transport facilities. As many of therestrictions from previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clockbombing attacks destroyed North Vietnam’s war-related logistical and supportcapabilities. Several B-52s were shotdown in the first days of the operation, but changes to attack methods and theuse of electronic and mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced airlosses. By the end of the bombingcampaign, few targets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnamwas forced to return to negotiations. OnJanuary 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leadingfour days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives fromNorth Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its ProvisionalRevolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris PeaceAccords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace inVietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; therelease and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American andother non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: apolitical settlement between the government and the PRG to determine thecountry’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunificationof North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Asin the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ didnot constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territoriesin South Vietnamwere allowed to remain in place.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

To assuage South Vietnam’sconcerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixonassured President Thieu of direct U.S.military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated theAccords. Furthermore, just before theAccords came into effect, the United Statesdelivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other alliedtroops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisorsremained. A peacekeeping force, calledthe International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnamto monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS becamepowerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant theend of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, asfighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations betweenJanuary-July 1973. President Nixon hadalso compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threatthat the United States wouldend all military and financial aid to South Vietnam, and that the U.S.government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill hispromise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had beenre-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated byanti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passedlegislation that prohibited U.S.combat activities in Vietnam,Laos, and Cambodia, without prior legislativeapproval. Also that year, U.S. Congresscut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government would keep itscommitment to provide military assistance.

Then in October 1973, a four-fold increase in world oilprices led to a global recession following the Organization of PetroleumExporting Countries (OPEC) imposing an oil embargo in response to U.S. support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. South Vietnam’seconomy was already reeling because of the U.S.troop withdrawal (a vibrant local goods and services economy had existed inSaigon because of the presence of large numbers of American soldiers) andreduced U.S.assistance. South Vietnam experienced soaring inflation,high unemployment, and a refugee problem, with hundreds of thousands of peoplefleeing to the cities to escape the fighting in the countryside.

The economic downturn also destabilized the South Vietnameseforces, for although they possessed vast quantities of military hardware (forexample, having three times more artillery pieces and two times more tanks andarmor than North Vietnam), budget cuts, lack of spare parts, and fuel shortagesmeant that much of this equipment could not be used. Later, even the number of bullets allotted tosoldiers was rationed. Compoundingmatters were the endemic corruption, favoritism, ineptitude, and lethargyprevalent in the South Vietnamese government and military.

In the post-Accords period, South Vietnam was determined toregain control of lost territory, and in a number of offensives in 1973-1974,it succeeded in seizing some communist-held areas, but paid a high price inpersonnel and weaponry. At the sametime, North Vietnamwas intent on achieving a complete military victory. But since the North Vietnamese forces hadsuffered extensive losses in the previous years, the Hanoigovernment concentrated on first rebuilding its forces for a planned full-scaleoffensive of South Vietnam,planned for 1976.