Daniel Orr's Blog, page 37

January 27, 2022

January 27, 1944 – World War II: The Siege of Leningrad ends

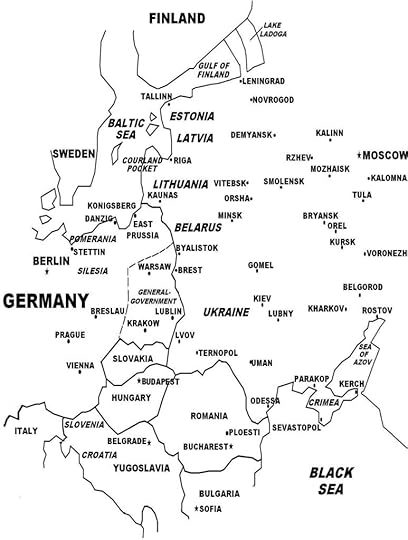

In September 1943, the Soviet High Command finalized plansfor a major offensive to finally eliminate the threat to Leningrad, and in the following months,massive troop buildup was made in the region under the cover of “maskirovka”(military deception) operations. OnJanuary 14, 1944, two Soviet Fronts (Volkhov and Leningrad), aided by elementsof 2nd Baltic Front, the combined force comprising 1.2 million troops, 4,600artillery pieces, 550 tanks, and 650 planes, attacked positions of German ArmyGroup North along the Leningrad sector. German Army Group North, comprising 700,000 troops, 2,400 artillerypieces, 150 tanks, and 140 planes, was by now a shadow of its once formidableself in 1941, as its armored and other elite units had been moved to othersectors and because its frontlines were lengthened in support of German Army Group Center. The Soviets broke through the defenses, andwithin two weeks, had forced German Army Group North to retreat 60 miles (100km) to the Luga River. On January 27, 1944, Stalin announced that the siege of Leningrad was over, andmilitary celebrations were held in the city. By early February 1944, German Army Group North had withdrawn to Narvaat the Estonian-Russian border, behind the Panther Line (the northern portionof the Panther-Wotan Line), which consisted of recently constructedfortifications that relied heavily on the natural defensive features of theregion, including the Narva and Velikaya Rivers, Lake Peipus, and the numerousdense forests and swamps.

(Taken from Siege of Leningrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

By late August 1941, German forces had captured the last RedArmy strongholds in the Baltic States in northern Estonia,forcing a Soviet naval evacuation of all Russian troops in Tallinn on August 27-31. By then also, German Army Group North’s 4thPanzer Group, now reinforced with 3rd Panzer Group, had advanced to within 30miles of Leningrad. The Finnish Army had retaken lost territories(from the Winter War) in Eastern Karelia and the Karelian Isthmus, and waspositioned 20 miles north of Leningrad. For Hitler, Leningrad not only served to protect thenorthern flank of Operation Barbarossa, it was also the main base of the SovietBaltic Fleet and a major center for industries and weapons production. Leningrad’scapture also would be devastating to Soviet morale, as it was Russia’s former capital and thebirthplace of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Ahead of the German advance, large numbers of Soviet troopswere transferred to Leningrad. On orders of the city’s administration,hundreds of thousands of residents built defensive fortifications around thecity, while 160,000 civilians joined the Red Army ranks. On September 8, 1941, the Germans cut thelast land route to Leningrad, and soon also thecity’s railway line to Moscow and Murmansk, thus isolatingthe city. On September 9, German ArmyGroup North launched its final attack on Leningrad,which initially made good progress but by September 19, met increasingly fierceresistance and mounting casualties in the last six miles to the city. On September 22, on orders of a by-nowimpatient Hitler, the Germans stopped their advance and began a siege of thecity, supported by air and artillery bombardment, to starve the population andinflict maximum destruction of infrastructures. This change of strategy from storming the city to conducting a siege wasbrought about by Hitler’s refusal to take on the responsibility of feeding thecity’s large population. The siege wasexpected to last a few weeks, at most until January 1942, when German forceswould enter Leningrad, deport the survivors to Siberia, and raze the city to the ground.

Some 1.7 million civilians were evacuated from Leningrad ahead of theGerman advance and during the siege, which soon reduced the pre-war populationof 3.3 million by nearly 50%. Theremaining population endured extreme hardships and a high death toll, withextremely limited food supplies, and disrupted water, heat, and other basicservices. At its peak in early 1942,some 100,000 people perished each month, mostly from starvation.

In November 1941, Soviet forces in Leningradopened an outlet through Lake Ladoga to unoccupiedSoviet territory in the east, known as the “Road of Life”, through which theentry of food supplies and evacuation of civilians were made. This route was a waterway for vessels duringthe warmer months and a highway for land vehicles during the colder seasons(when the lake surface froze to ice), but was extremely hazardous because ofconstant German air attacks, thus its other moniker, the “Road of Death”.

For the rest of World War II, the Germans did not launch anymajor offensives to capture Leningrad,as Hitler became focused on other sectors, and Army Group North’s ongoing siegebecoming a lower priority. The siege wasone of the longest and bloodiest in history.

January 25, 2022

January 25, 1918 – Finnish Civil War: General Mannerheim is appointed commander-in-chief

On January 25, 1918, theFinnish government appointed General Carl GustafEmil Mannerheim, a Finnishformer officer of the defunct Russian Imperial Army, as commander-in-chief ofall military forces and to organize the country’s armed forces, initially usingthe White Guards to carry out security functions. As a result of mandatory conscription of alladult males, General Mannerheim organized a fledging army and was helped inlarge part by the arrival of the first batch of Finnish Jäger soldiers (of theelite Prussian 27th Jäger Battalion, a German Army-trained unit made up ofFinnish volunteers that had fought for Germany in the Eastern Front), as wellas Swedish Army officers (Sweden became involved because of its determinationto stop Bolshevik revolutionary ideas from entering its territory).

(Taken from Finnish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

War Atthe start of the war, the Red Guards nominally held a military advantage overthe White forces. A high volunteerengagement raised the numerical strength of the Red Guards; at its peak, theRed Guards numbered between 100,000 and 140,000 fighters. Meanwhile, the Finnish Army, initiallyconsisting of the White Guards, had its ranks filled with conscripts, many ofwhom belonged to workers and peasant backgrounds and therefore were yet to betested for commitment to the White cause; at its peak, the Finnish Army hadbetween 70,000 and 100,000 soldiers. Atthe start of hostilities, some 80,000 Russian soldiers remained in Finland,whom Lenin had intended to fight alongside the Red Guards in support of RedFinland. However, the Russian soldierswere demoralized and war-weary, and most cared little for the situation in Finland and longed only to return home to Russia. Furthermore, commitment to Bolshevism alsowas uncertain among them, and some Russian officers even helped GeneralMannerheim, their fellow co-officer in the Russian Imperial Army, to secureweapons stockpiles in Russian garrisons and bases in Finland. Ultimately, some 4,000 to 7,000 Russian Armypersonnel aided the Red Guards, mostly in training and technical functions.

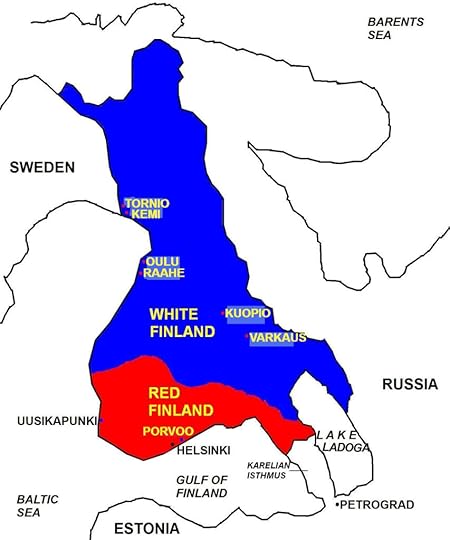

Because of the urgentneed to bring troops to the frontlines, White and Red forces were assembledquickly and thus often received inadequate training. As a result, the conflict is referred tosometimes as the “War of the Amateurs”. The Red Guards took the strategic initiative early in the war,consolidating their strongholds in the economically important, industrialsouthern regions. White forcescontrolled, except for pockets of isolated areas, nearly all of the northernregions (Figure 25). By the first weekof February 1918, a frontline was established between the opposing forces.

February 1918 saw the twosides launch operations to seize isolated pockets of territory still held bythe other side inside their main areas of control: the Red forces controlledthe towns of Varkaus, Kuopio, Oulu, Raahe, Kemiand Tornio in White Finland, while Whiteforces held Porvoo, Kirkkonummi and Uusikaupunki in Red Finland. As early as mid-January 1919, the two sides werevying for control of the railway lines in order to gain access to weapons beingtransported by rail and to allow rapid movement of their troops, weapons, andsupplies. In late January 1918, ashipment of Russian weapons sent by Lenin for the Red Guards led to armedclashes between Reds and Whites at the railway lines near Viipuri, aRed-controlled town located north of the Karelian Isthmus;the Viipuri region was bitterly contested throughout the war.

White Finland and Red Finland

Meanwhile, the German-Russianpeace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk (to end German-Russian hostilities in WorldWar I) were going nowhere. On February10, 1918, the Russian delegation walked out in protest that the territorialdemands being imposed by the Central Powers on Russia were excessive. On February 17, 1918, the Central Powersrepudiated the December 1917 ceasefire agreement, and the following day, Germany and Austria-Hungaryrestarted hostilities, launching a massive offensive with one million troops in53 divisions along three fronts that swept through western Russia and captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia,and Estonia. Eleven days into the offensive, the northernfront of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capital ofPetrograd (on March 12, 1918, the Russian government transferred its capital toMoscow).

On February 23, 1918, orfive days into the offensive, peace talks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, withthe Central Powers demanding from Russia even greater territorial and militaryconcessions than in the earlier negotiations. After heated debates among members of the Council of People’s Commissars(the highest Russian governmental body) who were undecided whether to continueor end the war, at the urging of Lenin, the Russian government agreed to acceptthe Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On March 3,1918, Russian and Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whichincluded the following major stipulations: peace was restored between Russiaand the Central Powers; Russia formally relinquished possession of Finland(whose independence it had already recognized in December 1917), Belarus,Ukraine, and the Baltic territories of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – Germanyand Austria-Hungary were to determine the future of these territories; andRussia also agreed on some territorial concessions to the Ottoman Empire.

The February 1918 Germanoffensive had major repercussions for Finland,as the German-Russian rivalry in World War I spilled over into Finlandand soon merged with the Finnish Civil War. Germanyhad backed White Finland by providing weapons and sending FinnishJäger soldiers to provide training for the Finnish (White) Army in order toundermine Soviet Russia, which supported socialist Red Finland. But following a request by the Whitegovernment on February 14, 1918 for direct assistance, on March 5, 1918 Germanyintervened by landing advance units on Åland Islands in preparation to anamphibious landing on the Finnish mainland.

Just as Germany’sinvolvement increased, Soviet Russia, complying with the Treaty ofBrest-Litovsk, withdrew its remaining forces in Finland. By the end of March 1918, the Finnish CivilWar had turned invariably in favor of the White forces, brought about also byother reasons: General Mannerheim proved to be a proficient commander; theJäger and Swedish officers had raised the competence and morale of the Finnish(White) Army; and modern German weapons were arriving in greaterquantities. Meanwhile, the Red Guards,already weakened by the withdrawal of the Russian Army, also suffered from achronic lack of capable military and political leadership, inadequate training,and weapons shortages. Furthermore, RedGuard field officers were voted into their positions by consensus amongrank-and-field soldiers (rather than competence), which compromised disciplineand reduced resoluteness in battle.

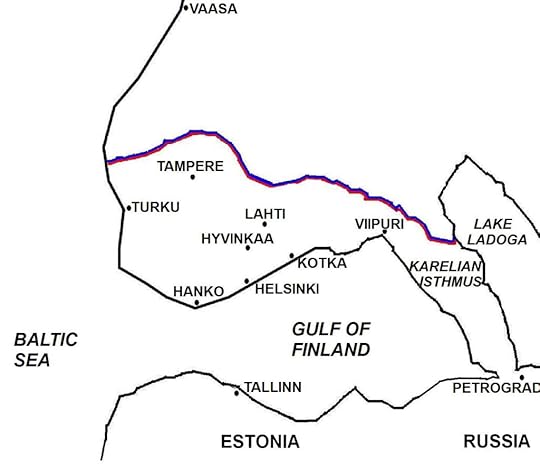

In March 1918, Whiteforces launched a series of offensives that brought the war to an end. On the 15th of that month, theFinnish (White) Army broke through the Vilppula Front (the western sector ofthe war) and advanced rapidly south toward Tampere, a major Red stronghold. Kuru, Lankipohja, and Vehmainen werecaptured, forcing the Red Guards to retreat to Tampere. Meanwhile, other White units advanced from the east and south, reachingthe eastern suburbs of Tampere on March 23, 1918. Four days later, the city was encircled. A Red Guard counter-attack to relieve thecity failed and by April 3, 1918, White forces, now reinforced with Jägerand Swedish units, launched the final attack on the city, which fell on April6. The Battle of Tampere, which saw someintense urban street-to-street and house-to-house fighting, was one of thegreatest engagements of the war; a combined 30,000 combatants were involved,and some 2,000 were killed on both sides while 11,000 Red Guards were captured.

Occurring nearly simultaneously with the Whiteforces’ final offensive on Tampere,some 10,000 German Army troops of the Baltic Sea Division landed at Hanko, offthe southern coast, on April 3, 1918; four days later, another German unit, theDetachment Brandenstein consisting of 3,000 soldiers, landed at Loviisa. The Germans moved rapidly toward Helsinki, taking RedFinland’s capital on April 13. Germanforces from the south and the Finnish (White) Army from the north then advancedtoward Red strongholds north of Helsinki,capturing Lahti,Hyvinkää, Riihimäki, and Hämeenlinnaby the third week of April 1918.

Finnish Civil War

By late April, Viipuri, Red Finland’s capital afterevacuating Helsinki,also came under pressure from White forces. On April 29, 1918, a Finnish (White) Army offensive consisting of 18,000troops captured the city, which effectively ended Red Finland as a sovereignentity. A few days earlier, RedFinland’s political and military leaders had fled the city into Soviet Russia,leaving behind some 15,000 Red Guards who were taken prisoner after the battle. On May 5, 1918, the Kymenlaaksoregion, the last major Red territory, fell when White forces captured Kouvolaand Kotka. By mid-May 1918, the KarelianIsthmus was in White possession; in the wake of Red Finland’s defeat, thousandsof socialist supporters fled to Russia,all the while subjected to attacks by White forces.

The war was over; some 38,000 lost their lives, 25%in the fighting, and 75% by war-related violence. Both sides committed many atrocities againstsupporters of the opposing side, acts which were carried out by military andparamilitary forces without the consent and participation of the civilian Whiteand Red governments. The so-called RedTerror (by Red forces), which took place in territories of Red Finland,targeted conservative politicians, landowners, businessmen/industrialists, andother White supporters; some 1,600 were killed. The White Terror (by White forces) targeted socialistpoliticians and leaders, Red Guards, Red Finland officials, as well as RedFinland-allied Russian soldiers; some 7,000 to 10,000 were killed. White Terror also extended to the 80,000 Redsupporters and fighters who were imprisoned after the war. Poor prison conditions and inadequate foodrations led to some 13,000 prisoner deaths, and individual prisonersexperienced as high as 20% to 30% mortality rates. While Red Terror was sporadic, random, and mostly involvedpersonal motives, White Terror was much more systematic and organized.

January 23, 2022

January 23, 1973 – Vietnam War: Negotiations in Paris resume, leading to a peace treaty four days later

On January23, peace negotiations in Paris resumed, leading four days later, on January27, 1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional RevolutionaryGovernment (PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement onEnding the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked theend of the war. The Accords stipulated aceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of allAmerican and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for SouthVietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determinethe country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunificationof North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Asin the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ didnot constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territoriesin South Vietnamwere allowed to remain in place.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

Peace negotiations Since it began in May 1968, the peace talks in Paris had made littleprogress. Negotiations were held at themain conference hall. However, sinceFebruary 1970, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and NorthVietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho had been holding secret talks separate fromthe main negotiations. These secrettalks achieved a breakthrough on October 17, 1972 (ten days after the U.S.bombings had forced North Vietnam to return to negotiations), when Kissingerannounced that “peace is at hand” and that a mutually agreed draft of a peaceagreement was to be signed on October 31, 1972.

However,South Vietnamese President Thieu, when presented with the peace proposal, refusedto agree to it, and instead demanded 129 changes to the draft agreement,including that the DMZ be recognized as the international border of a fullysovereign, independent South Vietnam, and that North Vietnam withdraw its forces from occupiedterritories in South Vietnam. On November 1972, Kissinger presented Thowith a revised draft incorporating South Vietnam’s demands as well aschanges proposed by President Nixon. This time, the North Vietnamesegovernment was infuriated and believed it had been deceived by Kissinger. On October 26, 1972, North Vietnam broadcast details ofthe document. In December 1972, talksresumed which went nowhere, and soon broke down on December 14, 1972.

Also onDecember 14, 1972, the U.S.government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return tonegotiations. On the same day, U.S.planes air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealingoff the coast to sea traffic. Then onPresident Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximumdestruction”, on December 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraftunder Operation Linebacker II, launchedmassive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoi andHaiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and othermilitary facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transportfacilities. As many of the restrictionsfrom previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacksdestroyed North Vietnam’swar-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the firstdays of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronicand mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, fewtargets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnamwas forced to return to negotiations. OnJanuary 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later,on January 23, negotiations resumed, leading four days later, on January 27,1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional Revolutionary Government(PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement onEnding the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked theend of the war. The Accords stipulated aceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of allAmerican and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for SouthVietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determinethe country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peacefulreunification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. As in the 1954 Geneva Accords (which endedthe First Indochina War), the DMZ did not constitute a political/territorialborder. Furthermore, the 200,000 NorthVietnamese troops occupying territories in South Vietnam were allowed toremain in place.

To assuage South Vietnam’s concerns regarding the last two points, on March15, 1973, President Nixon assuredPresident Thieu of direct U.S. military air intervention in case North Vietnamviolated the Accords. Furthermore, justbefore the Accords came into effect, the United States delivered a large amount of military hardware andfinancial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29,1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only asmall contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the InternationalCommission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitorand enforce the Accords’ provisions. Butas large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerlessand failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States,the Paris Peace Accords meant the end of the war, a view that was not shared bythe other belligerents, as fighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000ceasefire violations between January-July 1973. President Nixon had alsocompelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris PeaceAccords under threat that the United Stateswould end all military and financial aid to South Vietnam, and that theU.S. government would signthe Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill his promise ofcontinuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had beenre-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated byanti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passedlegislation that prohibited U.S.combat activities in Vietnam,Laos, and Cambodia, without prior legislativeapproval. Also that year, U.S. Congresscut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government would keep itscommitment to provide military assistance.

January 22, 2022

January 22, 1986 – Ugandan Bush War: Rebel forces lay siege to Kampala

On January 22, 1986, Museveni’s forces laid siege toKampala,capturing the city three days later. TheUgandan government collapsed, with its leaders fleeing into exile abroad. Thousands of Kampala residents took to the streets andwarmly received Museveni and the NRA fighters. On January 23, 1986, Museveni took over power and declared himselfpresident of Uganda. The civil war was over; between 300,000 and500,000 persons had lost their lives.

(Taken from Ugandan Bush War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

Background On April 11, 1979, General Idi Amin wasremoved from power when the Tanzanian Army, supported by Ugandan rebels,invaded and took over Uganda(previous article). Uganda then entered a transitionalperiod aimed at a return to democracy, a process that generated great politicalinstability. A succession of leadersheld power only briefly because of tensions between the civilian government andthe newly reorganized Ugandan military leadership. Furthermore, ethnic-based political partieswrangled with each other, hoping to gain and play a bigger role in the futuregovernment.

In general elections held in December 1980, formerPresident Milton Obote, who had been the country’s head of state before beingdeposed in a coup by General Amin in 1971, returned to power by winning thepresidential race. It was hoped that theelections would advance the country’s transition to democracy. Instead, they served as the trigger for thecivil war that followed. Defeatedpolitical groups accused President Obote of cheating to win the elections. Tensions rose within the already chargedpolitical atmosphere. Many armed groupsthat already existed during the war now rose up in rebellion against thegovernment.

War The Ugandan Civil War is historically cited ashaving started on February 6, 1981, when one of the armed groups attacked aUgandan military facility. The various rebel militias were tribe-based,operated independently of each other, and generally carried out theiractivities only within their local and regional strongholds. One such rebel militia consisted of formerUgandan Army soldiers still loyal to General Amin, and fought out of the WestNile District, which was GeneralAmin’s homeland. The various rebelmilitias had limited capability to confront government forces and thereforeemployed hit-and-run tactics, such as ambushing army patrols, raiding armoriesand seizing weapons, and carrying out sabotage operations against governmentinstallations.

The rebel group that ultimately prevailed in the warwas the National Resistance Army (NRA), led by Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s former Defense Minister. As a university student, Museveni hadreceived training in guerilla warfare, which he would later put to use in thewar.

January 21, 2022

January 21, 1968 – Vietnam War: North Vietnamese forces begin the 77-day siege of the U.S. base in Khe Sanh

The siege onKhe Sanh began on January 21, 1968 (ten days before the Tet Offensive), when 20,000 North Vietnamese troops, after manymonths of logistical buildup and moving heavy artillery into the heightssurrounding Khe Sanh, began a barrage of artillery, mortar, and rocketfire into the Khe Sanh combat base, which was defended by 6,000 U.S. Marinesand some elite South Vietnamese troops. Another 20,000 North Vietnamese troops served as reinforcements and alsocut off road access to Khe Sanh, sealing off, and thus surrounding, thebase. The 77-day battle featured 1. artilleryduels by both sides; 2. Khe Sanh being supplied solely by air; 3. NorthVietnamese probing attacks on the Khe Sanh base; and 4. North Vietnameseassaults to dislodge U.S. Marines outposts situated on a number of nearbystrategic hills.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

Khe Sanh While the Tet Offensive was ongoing,General Westmoreland continued tobelieve that the Tet Offensive was a diversion for a major North Vietnameseattack in the north, particularly on the Khe Sanh American combat base, inpreparation for a full invasion of South Vietnam’s northern provinces. Thus, he sent back only few combat troops already committed to defendthe towns and cities. After the war,North Vietnamese officials have since insisted that the Tet Offensive was theirmain objective, and that their attack on Khe Sanh was merely a diversion todraw away U.S.forces from the Tet Offensive. Somehistorians also postulate that North Vietnam planned no diversion at all, butthat its purpose was to launch both the Khe Sanh and Tet offensives.

Based on thesecond scenario, North Vietnamplanned the siege at Khe Sanh as a repetition of its successful 1954 siege ofthe French base at Dien Bien Phu. A NorthVietnamese victory at Khe Sanh would have the Americans meet the same fate asthe French at Dien Bien Phu. Conversely, the U.S. military wanted Khe Sanh to bea major showdown with the North Vietnamese Army, where overwhelming Americanfirepower would be brought to bear in battle and inflict serious losses on theenemy.

The siege onKhe Sanh began on January 21, 1968 (ten days before the Tet Offensive), when 20,000 North Vietnamese troops, after manymonths of logistical buildup and moving heavy artillery into the heightssurrounding Khe Sanh, began a barrage of artillery, mortar, and rocketfire into the Khe Sanh combat base, which was defended by 6,000 U.S. Marinesand some elite South Vietnamese troops. Another 20,000 North Vietnamese troops served as reinforcements and alsocut off road access to Khe Sanh, sealing off, and thus surrounding, thebase. The 77-day battle featured 1. artilleryduels by both sides; 2. Khe Sanh being supplied solely by air; 3. NorthVietnamese probing attacks on the Khe Sanh base; and 4. North Vietnameseassaults to dislodge U.S. Marines outposts situated on a number of nearbystrategic hills.

In earlyApril 1968, the Siege of Khe Sanh ended, with U.S. air firepower being thedecisive factor. By then, American B-52bombers had dropped some 100,000 tons of bombs (equivalent to five Hiroshima-sizeatomic bombs), which wreaked havoc on North Vietnamese positions. U.S.bombing also destroyed the extensive network of trenches which the NorthVietnamese were building to inch ever closer to U.S. positions. The North Vietnamese planned to use thetrenches as a springboard for their final assault on Khe Sanh. (The Viet Minh had usedthis tactic to overrun the Dien Bien Phu base in1954.) North Vietnamese forces retreatedto Laos and North Vietnam. Combat fatalities during the siege of KheSanh included 270 Americans, 200 South Vietnamese, and 10,000 North Vietnamesesoldiers.

January 20, 2022

January 20, 1972 – Pakistan begins developing nuclear weapons following its defeat in the Indian-Pakistan War of 1971

On January 20, 1972, Pakistanlaunched its nuclear weapons program in the aftermath of its defeat to India in 1971 which also led to East Pakistangaining its independence from Pakistanas the new state of Bangladesh.In May 1998, Pakistanconducted its first nuclear tests, the seventh country to do so.

(Taken from Bangladesh War of Independence / Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

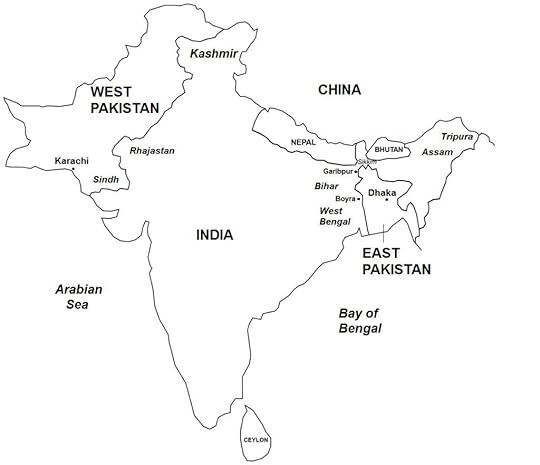

Background In 1947, the Indian subcontinent waspartitioned (previous article) intotwo new countries (Map 13): theHindu-majority Indiaand the nearly exclusive Muslim Pakistan. Much of India wasformed from the subcontinent’s central and eastern regions, while Pakistan comprised two geographically separateregions that became West Pakistan (located in the northwest) and East Pakistan (located in the southeast).

From its inception, Pakistanexperienced a great disparity between West Pakistan and East Pakistan. The national capital was located in West Pakistan, from where all major political andgovernmental decisions were made. Military and foreign policies emanated from there as well. West Pakistanalso held a monopoly on the country’s financial, industrial, and socialaffairs. Much of the country’s wealthentered, remained in, and was apportioned to the West. These factors resulted in West Pakistan beingmuch wealthier than East Pakistan. And all this despite East Pakistan having ahigher population than West Pakistan.

Bangladesh War of Independence and Indian-Pakistani War of 1971

In the 1960s, East Pakistancalled for social and economic reforms and greater regional autonomy, but wasignored by the national government. Thenin 1970, the Amawi League, East Pakistan’s mainpolitical party, won a stunning landslide victory in the national elections,but was prevented from taking over the government by the rulingcivilian-military coalition regime, which feared that a new civilian governmentwould reduce the military’s influence on the country’s political affairs.

Leaders from East Pakistan and West Pakistan tried to negotiate a solution to the political impasse,but failed to reach an agreement. Havingbeen prevented from forming a new government, Mujibur Rahman, East Pakistan’s leader, called on East Pakistanis to carry out acts ofcivil disobedience.

In Dhaka, the EastPakistani capital, thousands of residents undertook mass demonstrations thatparalyzed commercial, public, and civilian functions. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani Armyarrested and jailed Mujibur, who then declared while in prison the secession ofEast Pakistan from Pakistanand the founding of the independent state of Bangladesh. Mujibur’s supporters aired the declaration ofindependence on broadcast radio throughout East Pakistan.

East Pakistanis then organized the Mukti Bahini, a guerilla militiawhose ranks were filled by ethnic Bengali soldiers who had defected from thePakistani Army. As armed clashes beganto break out in Dhaka, the national government sent more troops to East Pakistan. Much of the fighting took place in April-May 1971, where governmentforces prevailed, forcing the rebels to flee to the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura. The Pakistani Army then turned on the civilian population to weed outnationalists and rebel supporters. Thesoldiers targeted all sectors of society – the upper classes of the political,academic, and business elite, as well as the lower classes consisting of urbanand rural workers, farmers, and villagers. In the wave of violence and suppression thattook place, tens of thousands of East Pakistanis were killed, while some tenmillion civilians fled to the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura,Assam, Bihar,and Meghalaya.

As East Pakistani refugees flooded into India,the Indian government called on the United Nations (UN) to intervene, butreceived no satisfactory response. Asnearly 50% of the refugees were Hindus, to the Indian government, this meantthat the causes of the unrest in East Pakistanwere religious as well as political. (During the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, a massivecross-border migration of Hindus and Muslims had taken place; by the 1970s,however, East Pakistan, still contained a significant 14% Hindu population.)

Since its independence, Indiahad fought two wars against Pakistanand faced the perennial threat of fighting against or being attackedsimultaneously from East Pakistan and West Pakistan. Indiatherefore saw that the crisis in East Pakistan yielded one benefit – if thethreat from East Pakistan was eliminated, India would not have to face thethreat of a war on two fronts. Thus,just two days into the uprising in East Pakistan,India began to secretlysupport the independence of Bangladesh. The Indian Army covertly trained, armed, andfunded the East Pakistani rebels, which within a few months, grew to a force of100,000 fighters.

In May 1975, Indiafinalized preparations for an invasion of East Pakistan,but moved the date of the operation to later in the year when the Himalayanborder passes were inaccessible to a possible attack by the Chinese Army. Indiahad been defeated by Chinain the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and thus was wary of Chinese intentions, more sosince China and Pakistan maintained friendly relations and bothconsidered Indiatheir common enemy. As a result, India entered into a defense treaty with theSoviet Union that guaranteed Soviet intervention in case India was attacked by a foreignpower.

In late spring and summer of 1971, East Pakistanirebels based in West Bengal entered East Pakistanand carried out guerilla attacks against the Pakistani Army. These infiltration attacks includedsabotaging military installations and attacking patrols, outposts, and otherlightly defended army positions. Government forces threw back the attacks and sometimes entered into Indiain pursuit of the rebels.

By October 1971, the Indian Army became involved inthe fighting, providing artillery support for rebel infiltrations and evenopenly engaging the Pakistani Army in medium-scale ground and air battles alongthe border areas near Garibpur and Boyra (Map 14).

War India’sinvolvement in East Pakistan was condemned in West Pakistan, where war sentiment was running high by November1971. On November 23, Pakistan declared a state of emergency anddeployed large numbers of troops to the East Pakistani and West Pakistaniborders with India. Then on December 3, 1971, Pakistani planeslaunched air strikes on air bases in India,particularly those in Jammu and Kashmir, Indian Punjab, and Haryana.

The next day, India declared war on Pakistan. India held a decisive militaryadvantage, which would allow its armed forces to win the war in only 13days. Indiahad a 4:1 and 10:1 advantage over West Pakistan and East Pakistan, respectively, in terms of numbers of aircraft, allowingthe Indians to gain mastery of the sky by the second day of the war.

India’sobjective in the war was to achieve a rapid victory in East Pakistan before theUN imposed a ceasefire, and to hold off a possible Pakistani offensive from West Pakistan. Inturn, Pakistan hoped to holdout in East Pakistan as long as possible, and to attack and make territorialgains in western India,which would allow the Pakistani government to negotiate in a superior positionif the war went to mediation.

In the western sector of the war where opposingforces were more evenly matched, the fighting centered in threevolatile areas: Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab,and Sindh-Rhajastan. Pakistan launched offensives that were generallyunsuccessful, except in Chamb, a town in Kashmirwhich its forces overran and held temporarily. In the Longewal Desert in India’sRajasthan State, a Pakistani armored thrust wasthwarted by an Indian air attack, which resulted in heavy Pakistani losses.

January 19, 2022

January 19, 1960 – Algerian War of Independence: French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle dismisses General Jacques Massu

French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle weakened the FrenchAlgerian Army’s radicalism when on January 19, 1960, he dismissed GeneralJacques Massu, victor of the Battle of Algiers, who had threatenedinsubordination by declaring that he and other officers may choose to notfollow de Gaulle’s orders. Three months later, in April 1960, de Gaullereassigned General Challe, commander-in-chief of the French Algerian Army, awayfrom Algeria, just as the latter was on the verge of inflicting a decisivedefeat on the FLN “internal” forces.

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

General Massu’s dismissal sparked the “Week of Barricades”(French: La semaine des barricades)starting on January 24, 1960, where some 30,000 pieds-noirs took to thestreets, seized government buildings, and set up barricades in an act ofdefiance against de Gaulle’s government. Viewing these acts as a threat to his regime, de Gaulle, donning hisWorld War II brigadier general’s uniform in a televised broadcast on January29, 1960, appealed to the French people and armed forces to remain loyal to France. The French 10th Parachute Division, which hadwon the Battle of Algiers for France,did not launch suppressive action against the barricades, but the refusal ofthe French Army to join the protesters doomed the uprising. The French 25th Parachute Division finallybroke up the barricades; casualties for the protesters were 22 dead and 147wounded, and for the Algerian gendarmes (police), 14 dead and 123 wounded.

A further sign of de Gaulle’s shift in policy toward Algeria took place in June 1960 when he took upa truce offer by a regional leader of the National Liberation Front (FLN;French: Front de Libération Nationale)and negotiate a “warrior’s peace” (French: lapaix des braves); however, peace talks held in Melun (in France) failed. Then by November 1960, de Gaulle had decidedon Algeria’sfate. On November 4, he declared that“there will be an Algerian republic one day, which will not be France”. He further stated a “new course”, i.e. an“emancipated Algeria…which,if the Algerians so desire…will have its own government, its institutions, andits laws”. De Gaulle then prepared areferendum for France and Algeria to determine whether Algeria should be givenself-determination.

By the early 1960s, de Gaulle was shifting his foreign andeconomic priorities to Europe primarily by boosting France’srapidly improving relations with Germany,which ultimately led to the signing, together with Italy,Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg, of the Treaty of Romein March 1957 that established the European Economic Council (EEC, precursor ofthe European Union). Furthermore, in thecontext of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union, de Gaulle wanted to make France,despite its alignment with the West through the North Atlantic TreatyOrganization (NATO), a political and military “third force” separate from thetwo superpowers.

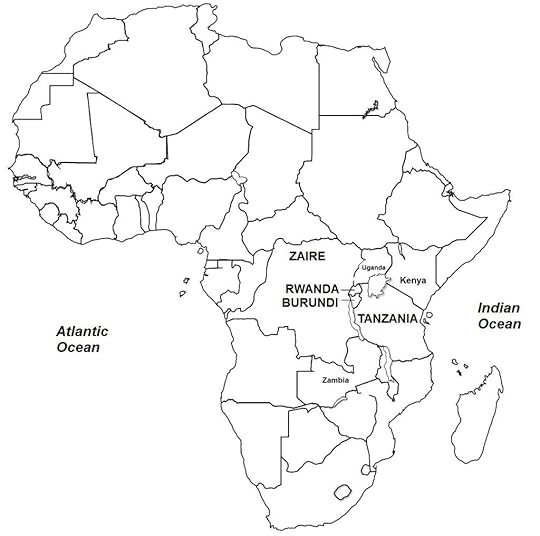

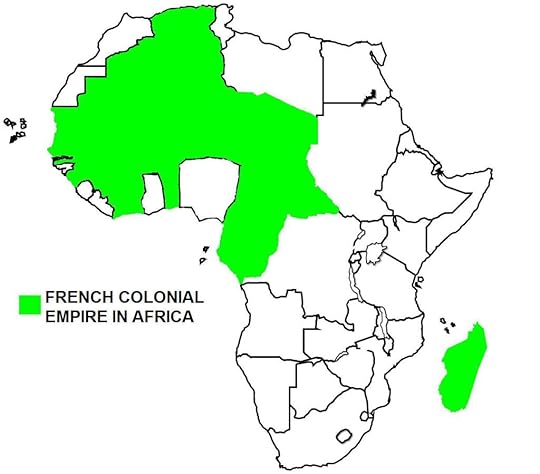

De Gaulle’s plan to disengage from Algeria was merely one episode in thedecolonization process that Francehad undertaken in Africa in 1960: by the end of that year, the once vast French West Africa had given way to 13 independentcountries. Similarly, the British Empire(which together with France held the greatest colonial territorial share ofAfrica) also had begun the process of decolonization in 1960 (apart from Ghana,which gained independence in 1957), having been triggered in February of thatyear when British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan issued his “Wind of Change”speech, declaring that in Africa, “the wind of change is blowing” and “whetherwe like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a politicalfact”. Also in 1960, Belgium turned over political authority to anewly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo and would do the same to Rwandaand Burundiin 1962. Portugaland Spaintried to hold onto their African possessions, but in the ensuing years, becamemired in long and bitter independence wars against indigenous nationalistmovements.

Furthermore, on December 14, 1960, the United Nations GeneralAssembly (UNGA) passed Resolution 1514 (XV) titled “Declaration of the Grantingof Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, which establisheddecolonization as a fundamental principle of the UN. Five days later, on December 19, the UN releasedUNGA Resolution 1573 that recognized the right of self-determination of theAlgerian people.

On January 8, 1961, in a referendum held in France and Algeria,75% of the voters agreed that Algeriamust be allowed self-determination. TheFrench government then began to hold secret peace negotiations with theFLN. In April 1961, four retired FrenchArmy officers (Generals Salan, Challe, André Zeller, and Edmond Jouhaud, andassisted by radical elements of the pied-noir community) led the French commandin Algiers in a military uprising that deposed the civilian government of thecity and set up a four-man “Directorate”. The rebellion, variously known as the 1961 Algiers Putsch (French: Putsch d’Alger) or Generals’ Putsch(French: Putsch des Généraux), was acoup to be carried out in two phases: taking over authority in Algeria with thedefeat of the FLN and establishment of a civilian government; and overthrowingde Gaulle in Paris by rebelling paratroopers based near the French capital.

De Gaulle invoked the constitution’s provision that gave himemergency powers, declared a state of emergency in Algeria, and in a nationwidebroadcast on April 23, appealed to the French Army and civilian population toremain loyal to his government. TheFrench Air Force flew the empty air transports from Algeriato southern France toprevent them from being used by rebel forces to invade France, while the French commands in Oran and Constantineheeded de Gaulle’s appeal and did not join the rebellion. Devoid of external support, the Algiersuprising collapsed, with Generals Challe and Zeller being arrested and laterimprisoned by military authorities, together with hundreds of other mutineeringofficers, while Generals Salan and Jouhaud went into hiding to continue the strugglewith the pieds-noirs against Algerian independence.

On April 28, 1961, in the midst of the uprising, Frenchmilitary authorities test-fired France’s first atomic bomb in the SaharaDesert, moving forward the date of the detonation ostensibly to prevent thenuclear weapon from falling into the hands of the rebel troops. The attempted coup dealt a serious blow toFrench Algeria, as de Gaulle increased efforts to end the war with the Algeriannationalists.

In May 1961, the French government and the GPRA (the FLN’sgovernment-in-exile) held peace talks at Évian, France, whichproved contentious and difficult. But onMarch 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called the Évian Accords,which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the following day) and arelease of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were: Frenchrecognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeing theprotection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French militarybases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privilegedAlgerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the developmentof Algeria’s nascent oil industry.

In a referendum held in France on April 8, 1962, over 90% ofthe French people approved of the Évian Accords; the same referendum held inAlgeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearly six million voting in favor of theagreement while only 16,000 opposed it (by this time, most of the one millionpieds-noirs had or were in the process of leaving Algeria or simply recognizedthe futility of their lost cause, thus the extraordinarily low number of “no”votes).

However, pied-noir hardliners and pro-French Algeriamilitary officers still were determined to derail the political process,forming one year earlier (in January 1961) the “Organization of the SecretArmy” (OAS; French: Organisation del’armée secrète) led by General Salan, in a (futile) attempt to stop the1961 referendum to determine Algerian self-determination. Organized specifically as a terror militia,the OAS had begun to carry out violent militant acts in 1961, whichdramatically escalated in the four months between the signing of the ÉvianAccords and the referendum on Algerian independence. The group hoped that its terror campaignwould provoke the FLN to retaliate, which would jeopardize the ceasefirebetween the government and the FLN, and possibly lead to a resumption of thewar. At their peak in March 1962, OASoperatives set off 120 bombs a day in Algiers,targeting French military and police, FLN, and Muslim civilians – thus, the warhad an ironic twist, as France and the FLN now were on the same side of theconflict against the pieds-noirs.

The French Army and OAS even directly engaged each other –in the Battle of Bab el-Oued, where French security forces succeeded in seizingthe OAS stronghold of Bab el-Oued, a neighborhood in Algiers, with combined casualties totaling 54dead and 140 injured. The OAS alsotargeted prominent Algerian Muslims with assassinations but its main target wasde Gaulle, who escaped many attempts on his life. The most dramatic of the assassinationattacks on de Gaulle took place in a Parissuburb where a group of gunmen led by Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, a Frenchmilitary officer, opened fire on the presidential car with bullets from theassailants’ semi-automatic rifles barely missing the president. Bastien-Thiry, who was not an OAS member, wasarrested, put on trial, and later executed by firing squad.

In the end, the OAS plan to provoke the FLN into launchingretaliation did not succeed, as the Algerian revolutionaries adhered to theceasefire. On June 17, 1962, the OAS theFLN agreed to a ceasefire. Theeight-year war was over. Some 350,000 toas high as one million people died in the war; about two million AlgerianMuslims were displaced from their homes, being forced by the French Army torelocate to guarded camps.

January 18, 2022

January 18, 1974 – Yom Kippur War: Egypt and Israel sign a Disengagement of Forces Agreement

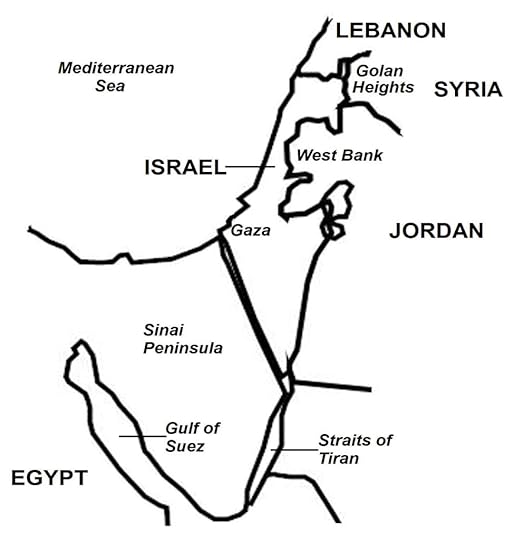

On January 18, 1974, Egyptand Israelsigned a Disengagement of Forces Agreement (also known as the Sinai IAgreement) following the Yom Kippur War. The agreement established a bufferzone between Egyptian and Israeli forces that was to be monitored by the UnitedNations Emergency Force (UNEF). Only a limited amount of armament and forceswere permitted inside the buffer zone.

On September 4, 1975, Egyptand Israelsigned the Sinai Interim Agreement (also known as Sinai II Agreement), whereboth sides pledged that conflicts between them “shall not be resolved bymilitary force but by peaceful means.” A further withdrawal was agreed, createda bigger UN buffer zone between their forces.

These agreements paved the way for the Camp David Accords(in Camp David, Maryland), which led to the signing of theEgypt-Israel Peace Treaty on March 26, 1979. The landmark treaty ended theirstate of war and normalization of relations, making Egyptthe first Arab state to officially recognize Israel. Diplomatic relationsbetween them came into effect in January 1980, with an exchange of ambassadorsthe following month. Israelwithdrew from the Sinai, which Egyptpromised to leave demilitarized. Israeli ships were allowed free passagethrough the Suez Canal, and Egyptrecognized the Strait of Tiran and Gulf of Aqabawas international waterways.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of 20th Century – Vol. 2)

Background Withits decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula andGaza Strip from Egypt, theGolan Heights from Syria,and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights wereintegral territories of Egyptand Syria,respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, togetherwith other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”,that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant thatonly armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula andGolan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently wasnot received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egyptcarried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and governmenttargets in the Sinai. In what is nowknown as the “War of Attrition”, Egyptwas determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israelto withdraw from the Sinai. By way ofretaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria,Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel,and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly becameinvolved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israeland Egyptto agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passedaway. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President AnwarSadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchlyhostile to Israel,President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeliconflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations(UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign apeace treaty with Israeland recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meirrefused to negotiate. President Sadat,therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging theIsraelis from the Sinai. He decided thatan Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israelto see the need for negotiations. Egyptbegan preparations for war. Largeamounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, butineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number ofruses. The Egyptian Army constantlyconducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoriceventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the truestrength of its armed forces. Thegovernment also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its warequipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated militaryhardware. Furthermore, when PresidentSadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egyptin July 1972, Israelbelieved that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakenedseriously. In fact, thousands of Sovietpersonnel remained in Egyptand Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syriancounterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized forwar.

Israel’sintelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the dateof the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbersof Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egyptand Syriaattacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiersand the entire Israeli Air Force. However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting awar and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carryingout a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War)to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur(which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, whenmost Israeli soldiers were on leave.

January 17, 2022

January 17, 1945 – World War II: Soviet forces recapture Warsaw

On January 12, 1945, the RedArmy finally launched its gigantic operation, called the Vistula-Oder Offensive, which was nothing short of a juggernaut. Large areas fell quickly, including Warsaw on January 19 and Lodz on January 21. In many areas, German units were encircledand destroyed, as Hitler forbade any retreat and ordered that the Wehrmachtmust fight to the death in these “fortresses”. Nevertheless, German forces at Krakowwithdrew just in time to avoid being surrounded and destroyed. Within two weeks, the Soviets had advanced200 miles to the Oder River at the German border, placing them to withinonly 43 miles from Berlin. The Soviet 1st Belorussian Front,comprising the northern thrust, also reached the Vistula Delta, cutting of East Prussia and the defending GermanArmy GroupCenter there, from Germany proper.

(Taken from Soviet Counter-Offensive and Defeat of Germany – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 6)

German-occupied Poland Operation Bagration’s conquest of Belarus in the summer of 1944 brought the RedArmy to the Vistula River and to within striking distance of Warsaw. On August 1, 1944, the main Polish resistanceorganization, called the Home Army, in response to Soviet encouragement tostart armed action, launched an uprising against the Germanoccupation forces in Warsaw. What ensued was a 63-day battle, which wasthe center of the much larger series of armed actions in other Polish citiesunder Operation Tempest,where the Germans crushed the uprising by October 1944 in fierce house-to-housefighting in the Polish capital. Materialsupport for the Polish fighters was in the form of a few supply drops byBritish and American planes, while Stalin stood down the Red Army that waspositioned in the nearby Vistulabridgeheads. The city of Warsaw, already heavilydamaged from the previous years’ fighting, was systematically razed to theground by the Germans in reprisal and in house-clearing operations. By the end of the war, the Polish capital was85% destroyed and became one of the most heavily devastated cities of World WarII.

In early January 1945, theRed Army in the Vistula was ready to launch the conquest of German-occupied Poland. Two Soviet Army Groups (the 1stBelorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts) were assembled, the combinedstrength comprising 2.2 million troops, 7,000 tanks, 13,800 artillery pieces,14,000 mortars, 4,900 anti-tank guns, and 2,200 Katyusha multiple-rocketlaunchers, and 8,500 planes, to confront German Army Group A, which was greatlyoutnumbered with 450,000 troops, 4,100 artillery pieces, and 1,100 tanks. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler dismissed this as “the greatest imposture since GenghisKhan”. Hitler also rejected the requestsby his generals to reinforce Polandby abandoning the Courland Pocket. Inthe lead-up to the fighting, some German military units withdrew fromindefensible areas. This German withdrawal triggered mass flight amongcivilians, and millions of ethnic Germans fled west to reach safety in centraland western Germany. German officials also closed down theconcentration camps in Poland,and forced the prisoners there into death marches to Germany in the winter cold wherethousands perished.

On January 12, 1945, the RedArmy finally launched its gigantic operation, called the Vistula-Oder Offensive, which was nothing short of a juggernaut. Large areas fell quickly, including Warsaw on January 19 and Lodz on January 21. In many areas, German units were encircledand destroyed, as Hitler forbade any retreat and ordered that the Wehrmachtmust fight to the death in these “fortresses”. Nevertheless, German forces at Krakowwithdrew just in time to avoid being surrounded and destroyed. Within two weeks, the Soviets had advanced200 miles to the Oder River at the German border, placing them to withinonly 43 miles from Berlin. The Soviet 1st Belorussian Front,comprising the northern thrust, also reached the Vistula Delta, cutting of East Prussia and the defending GermanArmy GroupCenter there, from Germany proper.

The Soviet 2ndBelorussian Front, whose diversion during the East Prussian campaign delayed 1stBelorussian Front’s advance to Berlin, nowcontinued to Pomerania, taking Danzig on March 28, 1945 and reaching Stettin on April 26.

Meanwhile to the south,Soviet 1st Ukrainian Front thrust across Silesia in two campaigns in February andMarch 1945, clearing the region of German forces, thereby securing the southernflank of 1st Belorussian Front. A broad front was formed stretching from Pomerania to Silesiaalong the Oder and Neisse rivers in preparation for the offensive on Berlin.

Berlin and defeat of Germany The Soviet offensive into Germany centered on Stalin’s twomain objectives: that the Red Army was to rapidly push far to the west aspossible to beat the Western Allies into capturing as much German territory aspossible; and that Berlin was to fall into Soviet hands, first, to deal withHitler and second, to gain possession of Germany’s nuclear researchprogram. For the campaign, Stalin taskedthree Soviet Army Groups, together with the Red Army’s best commanders: 1stBelorussian Front led by Marshal Georgy Zhukov; 2nd Belorussian Front led by MarshalKonstantin Rokossovsky, to the north of Zhukov’s forces; and 1stUkrainian Front led by Marshal Ivan Konev, to the south of Zhukov’s forces. The combined forces were massive: 2.5 milliontroops, including 200,000 Polish soldiers, 6,200 tanks, 42,000 artillerypieces, and 7,500 planes.

For the defense of outer Berlin, the Wehrmachtmustered 800,000 troops, 1,500 armored vehicles, 9,300 artillery pieces, and2,200 planes. The main defensive linesfor the eastern approaches to the city were located 56 miles (90 km) at Seelow Heightsand manned by German 9th Army. The German military had taken advantage of the delayed Soviet offensiveon Berlin toconstruct these defenses. The Germanspositioned these lines 10 miles (17 km) west of the Oder River,which would prove significant in the coming battle.

On April 16, 1945, the RedArmy launched its offensive, opening a preliminary massive artillerybombardment that landed on the mostly undefended banks of the Oder River. Soviet ground forces then advanced, with muchof the heaviest fighting centered on the strongly fortified Seelow Heights,where Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, comprising 1 milliontroops and 20,000 tanks advanced head on to German 9th Army’s100,000 troops and 1,200 tanks. By thefourth day, the Soviets had broken through, sustaining heavy losses of 30,000killed and 800 tanks destroyed, against 12,000 German casualties.

January 16, 2022

January 16, 1992 – Salvadoran Civil War: The government and rebels sign a peace agreement

In April 1990, the UNsucceeded in bringing together the two sides to Geneva, Switzerlandto hold peace talks. The war officiallyended on January 16, 1992, when the Salvadoran government, represented byPresident Cristiani, and five FMLN leaders who represented each of themovement’s five member-organizations, signed the Chapultepec Peace Accords at Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City.

(Taken from Salvadoran Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Background During the 1970s, El Salvador experienced greatsocial unrest as a result of a number of factors: an unstable politicalclimate, economic problems, an entrenched system of economic and socialinequalities, and a growing population competing for an increasingly limitedamount of resources. The long-repressedlower social classes, which form the vast majority of the population, hadbecome radicalized, and advocated both militant and violent methods ofexpression. In turn, the governmentimposed harsh measures against threats to its authority.

At the heart of theconflict was the country’s economically polarized social classes, the unequaldistribution of wealth, resources, and power between the smallSpanish-descended elite and the vast majority of Amerindian and mestizo (mixedAmerican-European descendants) populations. Since the colonial era when theSpanish Crown gave out vast tracts of lands to personal favorites through royalpatents, just 2% of the population (the so-called “Fourteen Families”) owned60% of all arable land, which subsequently was converted to latifundia, i.e.vast plantations that produced coffee beans, and later, sugarcane and cotton,for the lucrative export market. Some60% of the rural population did not own land, and of those who did, 95% of themowned farmlands too small to subsist on.

Apart from controllingthe economy, the biggest landowners held a monopoly on the governmental,political and military infrastructures of the country. Government policies favored the oligarchy andthus widened the economic gap, limiting available resources and opportunitiesto the lower classes, and relegating the vast majority to become (exploited)plantation farm hands in the primarily agricultural economy that existed formuch of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1932, peasants in thewestern provinces, supported by the nascent Salvadoran Communist Party, rose upin rebellion because of economic hardships caused by the ongoing GreatDepression. Government forces put downthe rebellion and then carried out a campaign of extermination against the Pipilindigenous population, whom they believed were communists who had supported theuprising that was aimed at overthrowing the government. Some 30,000 Pipil civilians were killed inthe military repression.

For nearly five decadesthereafter (1932-1979), the country was ruled by a long line of militaryleaders (under a façade of democracy), including one military-controlledcivilian government. The military’shard-line rule suppressed dissent and promoted the interests of the upperclass. But in 1959, Fidel Castro’scommunist victory in the Cuban Revolution profoundly altered the political andsecurity paradigm in the Western Hemisphere, and challenged for the first time United Stateshegemony and the region’s democratic, economic, and social institutions. Consequently, revolutionary groups sprung upall across Latin America to initiate armedstruggles aimed at toppling democratic and military governments, and thensetting up communist regimes.

In El Salvador, the localCommunist Party was revitalized after a long hiatus; in 1970, dissenting elementsthat advocated armed revolution broke away from the party and reorganized asthe PopularLiberation Forces “Farabundo Marti” (FPL; Spanish: Fuerzas Populares de Liberación“Farabundo Martí“), an armed group thatcarried out a rural-based guerilla war against the government. Other communist insurgent groups soon formedas well, including the People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP; Spanish: EjércitoRevolucionario del Pueblo), formed in 1972, and the National Resistance (RN;Spanish: LaResistencia Nacional), formed in 1975.

Revolutionary activity atthis time did not seriously threaten the government; the focus of leftistradicalism was on “mobilizing the masses”, where clandestine Marxist-leftistgroups organized or formed alliances with Salvadoran Communist Party-affiliatedpeasant groups, labor unions, and student movements that carried out laborstrikes, street protests, and media campaigns in San Salvador, the country’scapital, that called for reforms and better working and living conditions, aswell as create a climate that would encourage a general uprising. These clandestine groups often had an armedwing that conducted terror activities against conservative groups (landowners,businessmen, military officers, right-wing politicians, etc.), targeting themwith assassinations, kidnappings, and extortions. Worth noting is that while these clandestinegroups derived much of their support from the “masses”, they also receivedsubstantial financial backing from secret sympathizers from the upper classes,even some among the wealthiest.

In the 1960s, amiddle-ground political force emerged, the Christian Democratic Party, whichwas led by middle-class professionals who rejected left-wing and right-wingpolitics and advocated a moderate, centrist line that they believed led topolitical stability and greater economic parity, conditions that were favorableto the growth of the country’s middle class. These political centrists, led by José

NapoleónDuarte,initially had little support but soon expanded to become a major politicalforce by the early 1970s. In presidentialelections held in February 1972, Duartewon the popular vote, but the government used fraud that allowed the candidatewho was a military officer to win. Inthe highly charged, unstable climate of the Cold War, the right-wing governmentviewed politics of moderation as threatening and even communist-leaning.

The Salvadoran insurgencyreceived a great boost when in July 1979, Sandinista communist rebels in nearbyNicaraguadeposed pro-U.S. dictator Anastacio Somoza. In El Salvador, nowruled by General Carlos Humberto Romero, an increase in urban violence and ruralinsurgent action took place in the period leading up to the Marxist victory in Nicaragua. In response, the Salvadoran governmentintensified repressive measures in urban areas and military operations in thecountryside. In towns and cities, thegovernment’s internal security forces(National Guard, National Police, and Treasury Police) organized “death squads”to kill leaders of peasant, labor, and student organizations, leftistpoliticians, academics, journalists, and many others whom they regarded ascommunists. Hundreds were arrested andjailed, tortured, and executed or “disappeared”.

In October 1979, a groupof army officers, alarmed that the increasing violence was creating conditionsfavorable to a communist take-over similar to that which occurred in Nicaragua,carried out a coup that deposed General Romero. A five-member civilian and military junta, called the RevolutionaryJunta Government (JRG; Spanish: Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno

) was formed to rule the country until such that time that electionscould be held. In March 1980, after somerestructuring, Duartejoined the junta and eventually took over its leadership to become thecountry’s de facto head ofstate. The junta was openly supported bythe United States, whichviewed Duarte’s centrist politics as the bestchance to preserve democracy in El Salvador.

However, neither the coupnor the junta altered the power structures, and the military continued to wieldfull (albeit covert) authority over state matters. The junta implemented agrarian reform andnationalized some key industries, but these programs were strongly opposed bythe oligarchy. Militias and “deathsquads” that the junta ordered the military to disband simply were replacedwith other armed groups. The years 1980and 1981 saw a great increase in the military’s suppression of dissent.