Daniel Orr's Blog, page 36

February 6, 2022

February 6, 1922 – Interwar Period: Five major powers sign the Washington Naval Treaty

On February 6, 1922, five naval powers:United States, Britain, France,Italy, and Japan signed the Washington NavalTreaty, which restricted construction of the larger classes of warships. In April 1930, these countries signed theLondon Naval Treaty, whichmodified a number of clauses in the Washingtontreaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which wassigned only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, theprevious other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionistpolicies that required greater naval power.

(Taken from Events leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 6)

Post-WorldWar I Pacifism Because World War I had caused considerable toll on lives and broughtenormous political, economic, and social troubles, a genuine desire for lastingpeace prevailed in post-war Europe, and it was hoped that the last war would be“the war that ended all wars”. By themid-1920s, most European countries, especially in the West, had completedreconstruction and were on the road to prosperity, and pursued a policy ofopenness and collective security. Thispacifism led to the formation in January 1920 of the League of Nations (LN), an international organization which hadmembership of most of the countries existing at that time, including most majorWestern Powers (excluding the United States). The League had the following aims: to maintain world peace throughcollective security, encourage general disarmament, and mediate and arbitratedisputes between member states. In thepacifism of the 1920s, the League resolved a number of conflicts (and had somefailures as well), and by mid-decade, the major powers sought the League as aforum to engage in diplomacy, arbitration, and disarmament.

In September 1926, Germany ended its diplomatic near-isolation withits admittance to the League of Nations. This came about with the signing in December1926 of the Locarno Treaties (in Locarno, Switzerland), which settled the common bordersof Germany, France, and Belgium. These countries pledged not to attack eachother, with a guarantee made by Britainand Italyto come to the aid of a party that was attacked by the other. Future disputes were to be resolved through arbitration. The Locarno Treaties also dealt with Germany’seastern frontier with Polandand Czechoslovakia,and although their common borders were not fixed, the parties agreed thatfuture disputes would be settled through arbitration. The Treaties were seen as a high point in international diplomacy, and ushered in a climate of peacein Western Europe for the rest of the1920s. A popular optimism, called “thespirit of Locarno”,gave hope that all future disputes could be settled through peaceful means.

In June 1930, the last French troopswithdrew from the Rhineland, ending the Alliedoccupation five years earlier than the original fifteen-year schedule. And in March 1935, the League of Nationsreturned the Saar region to Germanyfollowing a referendum where over 90% of Saar residents voted to bereintegrated with Germany.

In August 1938, at the urging of the United States and France, the Kellogg-Briand Pact[1](officially titled “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument ofNational Policy”) was signed, which encouraged all countries to renounce warand implement a pacifist foreign policy. Within a year, 62 countries signed the Pact, including Britain, Germany,Italy, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. In February 1929, the Soviet Union, asignatory and keen advocate of the Pact, initiated a similar agreement, calledthe Litvinov Protocol, with itsEastern European neighbors, which emphasized the immediate implementation ofthe Kellogg-Briand Pact among themselves. Pacifism in the interwar period alsomanifested in the collective efforts by the major powers to limit theirweapons. In February 1922, the fivenaval powers: United States,Britain, France, Italy,and Japansigned the Washington Naval Treaty, which restricted construction of the largerclasses of warships. In April 1930,these countries signed the London Naval Treaty, whichmodified a number of clauses in the Washingtontreaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which wassigned only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, theprevious other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionistpolicies that required greater naval power.

An effort by the League of Nations andnon-League member United Statesto achieve general disarmament in the international community led to the WorldDisarmament Conference in Genevain 1932-1934, attended by sixty countries. The talks bogged down from a number of issues, the most dominantrelating to the disagreement between Germany and France, with the Germansinsisting on being allowed weapons equality with the great powers (or that theydisarm to the level of the Treaty of Versailles, i.e. to Germany’s currentmilitary strength), and the French resisting increased German power for fear ofa resurgent Germany and a repeat of World War I, which had caused heavy Frenchlosses. Germany,now led by Adolf Hitler (starting in January 1933), pulled out of theWorld Disarmament Conference, and in October 1933, withdrew from the League of Nations. The Genevadisarmament conference thus ended in failure.

[1] Named after U.S. Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and FrenchForeign Minister Aristide Briand.

February 5, 2022

February 5, 1988 – Panama’s dictator Manuel Noriega is charged in a U.S. court

In February 1988, grandjuries in Miami and Florida filed drug smuggling, moneylaundering, and racketeering lawsuits against General Noriega. Panamanian assets in the United States were frozen, which severelyaffected Panama that alreadywas reeling as a result of the United States suspension of military aid a yearearlier. In March 1988, a coup bysecurity officers failed to overthrow General Noriega. President Reagan alsobegan to explore more forceful ways to depose the Panamanian leader, butpreferably to be carried out by Panamanians, and supported or led by thePanamanian military.

(Taken from United States Invasion of Panama – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

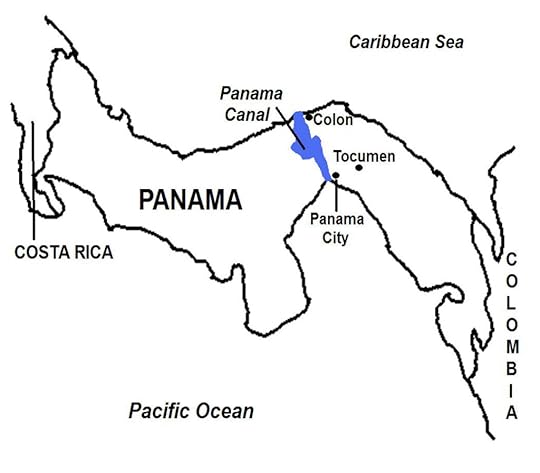

Background During the Cold War, the United States viewed Panamaas a vital and necessary ally in the Western Hemisphere, took great efforts tomaintain friendly relations with Panama, and provided substantialeconomic and military assistance to that Central American country. American interests in Panama centered on the Panama Canal, a shippingwaterway that linked the Pacific and AtlanticOceans through the Caribbean Sea. The U.S. government operated and de facto owned the Canal aftercompleting its construction in 1914. Forthe United States,the Canal was not only an enormous economic asset, generating large profitsfrom international shipping operations, but more important, it served as astrategic and political statement of American power in the region.

Panama had gained its independence on November 3, 1903 afterseceding from Colombia. The new country then signed a treaty with theUnited States that allowed the U.S.government, in exchange for monetarypayments to Panama, tofinish the construction of the Panama Canal,which had been abandoned by a French firm. The treaty also allowed the United States to operate andprotect the facility “in perpetuity”.

From the outset, mostPanamanians were opposed to the treaty, perceiving it as a violation of theircountry’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Opposition, particularly with regards to theperpetuity clause, grew over time, peaking in January 1964 when riots broke outin Panama City, Colon,and other areas when Panamanian students tried to raise the Panama flag in the Canal Zone. Some 28 people werekilled in the violence, including 4 U.S. soldiers.

International condemnation ofthe United States followed,prompting the U.S.government to open negotiations with Panamaon the future of the Panama Canal. These talks subsequently led to theTorrijos-Carter Treaties, signed in September 1977 (by U.S. President JimmyCarter and Panamanian de facto ruler,General Omar Torrijos), which stipulated the turn over of full control of thePanama Canal to Panama on December 31, 1999. Despite the treaties, U.S.forces continued to control the Panama Canal’s 14 military bases, which werelocated at the Pacific and Caribbean ends ofthe waterway.

Since its independence, Panamahad been ruled by a succession of civilian governments. In 1968, military officers overthrew thegovernment. General Torrijos, the coup’sleader, established a de factomilitary regime that ruled behind a façade of a civilian government that wassubservient to the military. Then inDecember 1983, the Panamanian armed forces came under the control of GeneralManuel Noriega who increased the military’s stranglehold over the country. In general elections held in May 1984,General Noriega manipulated the results of the presidential race to allow hischosen candidate to win.

In the early 1980s, Central America became a major battleground of the ColdWar. In search of support, the United Stateswas willing to ignore General Noriega’s abuses of power and have the Panamanianstrongman, a staunch anti-communist, as an ally. General Noriega already had a long-standingrelationship with the United States, having been an asset and informant of theCentral Intelligence Agency (CIA) since the early 1960s, and had even mediatedfor the U.S. government with Cuban leader Fidel Castro for the release of Americanprisoners in Cuba.

General Noriega transformed Panama into a center for smuggling cocaine andother narcotics from Colombiato the United Statesand other countries. He masterminded andled these operations and later asserted that the CIA and other U.S.government agencies knew and even supported these activities. Meanwhile in the United States, President Ronald Reagan was himself underpressure from an investigation by the U.S. Congress for possible involvement inthe “Iran-Contra Affair”, a covert operation where the U.S. government soldweapons to Iran (for the release of American hostages), and the proceeds werethen used to fund pro-U.S. “contra” rebels in Nicaragua.

Soon, relations betweenGeneral Noriega and the U.S.government deteriorated. Then as morereports from Panamaindicated General Noriega’s involvement in the drug trade, President Regan putpressure on the Panamanian leader, even urging him to step down fromoffice. President Reagan also wasalarmed at the increasing military repression and political instability in Panama,generated by growing opposition to General Noriega’s rule and governmentcorruption. General Noriega particularlywas condemned by the local opposition following the murder of Hugo Spadafora, agovernment critic who had returned to Panama to present evidence of themilitary leader’s involvement in the drug trade and other crimes. In response to public opposition to his rule,the Panamanian strongman released his forces, resulting in violent confrontationswhere many civilians were beaten up in street protests.

In February 1988, grandjuries in Miami and Florida filed drug smuggling, moneylaundering, and racketeering lawsuits against General Noriega. Panamanian assets in the United States were frozen, which severelyaffected Panama that alreadywas reeling as a result of the United States suspension of military aid a yearearlier. In March 1988, a coup bysecurity officers failed to overthrow General Noriega. President Reagan alsobegan to explore more forceful ways to depose the Panamanian leader, butpreferably to be carried out by Panamanians, and supported or led by thePanamanian military.

In January 1989, George H.W.Bush succeeded as the new U.S. President. By then, the Cold War was drawing to a close – at the end of 1989,Eastern Bloc countries had shed off communism for democracy, while the Soviet Union itself was on the verge of collapse. In Central America, the ongoing Cold Warconflicts also were winding down in response to the improving global securityand political climates, and the United States felt less the need to continuefunding its allies in the region. Forthe United States,General Noriega’s many faults, which long had been set aside because of hisstrong anti-communist position, now became too glaring to ignore.

Shortly after taking office,President Bush announced that one of his government’s domestic priorities wasto tackle the growing drug problem with a so-called “war on drugs’, aimed atexpanding a similar anti-drug campaign that had been in force since theprevious administration. A decadeearlier, Bush had served as CIA Director (in 1976) and had dealings withNoriega, who was then Panama’s intelligence chief and whose services wouldbecome vital for the United States in the heightened Cold War situation inCentral America from the late 1970s through most of the 1980s.

Now as U.S. head of state, President Bushsought to distance himself from General Noriega, and made a determined effortto remove the Panamanian leader from power. In May 1989, Panamaheld general elections. The U.S.government openly supported the main opposition party, hoping that a newgovernment would remove General Noriega as head of the newly created PanamaDefense Forces (the Panamanian military and police forces). As election results showed a clear defeat forthe government’s hand-picked presidential candidate, General Noriega stoppedthe tabulations and voided the elections, declaring that meddling by the UnitedStates (by supporting the opposition) had undermined the election’slegitimacy. Panama’s electoral tribunalconcurred, declaring that widespread fraud had taken place, tarnishing theresults. However, international pollobservers, which included former U.S. President Carter, concluded that theelections generally were free and fair, and that the opposition’s wide lead inthe results genuinely reflected the electorate’s choice. Mass rallies and demonstrations broke out in Panama City; GeneralNoriega responded by sending his paramilitary, called the Dignity Battalion,that attacked and broke up the crowds. In the melee, leading opposition candidates were beaten up, scenes ofwhich were caught by the television news media and aired in the United States. Thereafter, the Organization of AmericanStates (OAS) condemned the violence and joined the United States in calling forGeneral Noriega to resign which, however, was rejected by the Panamanianleader.

February 4, 2022

February 4, 1961 – Turmoil spreads in the Angolan War of Independence

On February 3, 1961, farm laborers in Baixa do Cassanje,Malanje, rose up in protest over poor working conditions. In the following days, the protest quicklyspread to many other regions, engulfing a wide area. The Portuguese were forced to send warplanesthat strafed and firebombed many native villages. Soon, the protest was quelled.

Occurring almost simultaneously with the workers’ protest,armed bands (believed to be affiliated with the MPLA) carried out attacks in Luanda, particularly inthe prisons and police stations, aimed at freeing political prisoners. The raids were repelled, with dozens ofattackers and some police officers killed. In reprisal, government forces and Portuguese vigilante groups attacked Luanda’s slums, where theykilled thousands of black civilian residents.

(Taken from Angolan War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

Background By the1830s, Portugal had lost Braziland had abolished its transatlantic slave trade. To replace these two valuable sources ofincome, Portugalturned to develop its African possessions, including their interior lands. In Angola, agriculture was developed,with the valuable export crops of coffee and cotton being grown in vastplantations. The mining industry wasexpanded.

Portugal’s development of the local economy, including theconstruction of public infrastructures such as roads and bridges, was carriedout using forced labor of black Africans, a system that was so harsh, ruthless,and akin to slavery. Consequently,thousands of natives fled from the colony. Indigenous lands were seized by the colonial government. And while Angola’s economy grew, only thecolonizers benefited, while the overwhelming majority of natives were neglectedand deprived of education, health care, and other services.

After World War II, thousands of Portuguese immigrantssettled in Angola. The world’s prices of coffee beans were high,prompting the Portuguese government to seek new white settlers in its Africancolonies to lead the growth of agriculture. However, many of the new arrivals settled in the towns and cities,instead of braving the harsh rural frontiers. In urban areas, they competed forjobs with black Angolans who likewise were migrating there in large numbers insearch of work. The Portuguese, beingwhite, were given employment preference over the natives, producing racialtension.

The late 1940s saw the rapid growth of nationalism in Africa. In Angola,three nationalist movements developed, which were led by “assimilados”, i.e.the few natives who had acquired the Portuguese language, culture, education,and religion. The Portuguese officiallydesignated “assimilados” as “civilized”, in contrast to the vast majority ofnatives who retained their indigenous lifestyles.

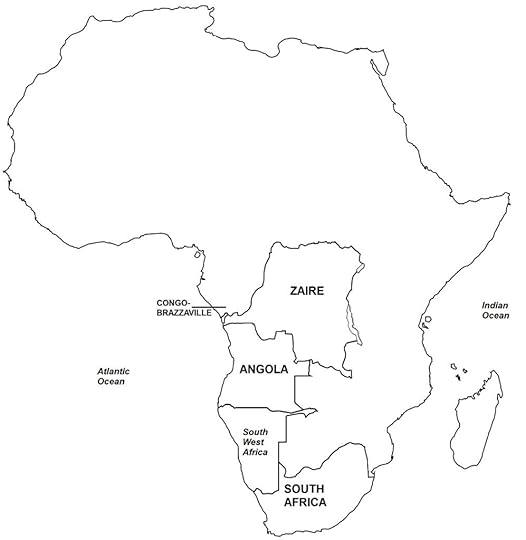

The first of these Angolan nationalist movements was thePeople’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola or MPLA (Portuguese: MovimentoPopular de Libertação de Angola)led by local communists, and formed in 1956 from the merger of the AngolanCommunist Party and another nationalist movement called PLUA (English: Party ofthe United Struggle for Africans in Angola). Active in Luanda and other major urban areas, the MPLAdrew its support from the local elite and in regions populated by the Ambunduethnic group. In its formative years, itreceived foreign support from other left-wing African nationalist groups thatwere also seeking the independences of their colonies from European rule. Eventually, the MPLA fell under the influenceof the Soviet Union and other communistcountries.

The second Angolan nationalist movement was the NationalFront for the Liberation of Angola or FNLA (Portuguese: Frente Nacional deLibertação de Angola). The FNLA was formed in 1962 from the mergerof two Bakongo regional movements that had as their secondary aim theresurgence of the once powerful but currently moribund Kingdom of Congo. Primarily, the FNLA wanted to end forcedlabor, which had caused hundreds of thousands of Bakongo natives to leave theirhomes. The FNLA operated out ofLeopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) in the Congofrom where it received military and financial support from the Congolesegovernment. The FNLA was led by HoldenRoberto, whose authoritarian rule and one-track policies caused the movement toexperience changing fortunes during the coming war, and also bring about theformation of the third of Angola’snationalist movements, UNITA.

UNITA or National Union for the Total Independence of Angola(Portuguese: União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) was foundedby Jonas Savimbi, a former high-ranking official of the FNLA, overdisagreements with Roberto. Unlike theFNLA and MPLA, which were based in northern Angola, UNITA operated in thecolony’s central and southern regions and gained its main support from theOvibundu people and other smaller ethnic groups. Initially, UNITA embraced Maoist socialismbut later moved toward West-allied democratic Africanism.

February 3, 2022

February 3, 1961 – Angolan War of Independence: Farm workers protest poor working conditions, starting the rebellion

On February 3, 1961, farm laborers in Baixa do Cassanje, Malanje, rose up in protest over poorworking conditions. The protest quickly spread to many other regions, engulfinga wide area. The Portuguese were forced to send warplanes that strafedand firebombed many native villages. Soon, the protest was quelled.

Occurring almost simultaneously with the workers’ protest,armed bands (believed to be affiliated with the MPLA) carried out attacks in Luanda, particularly inthe prisons and police stations, aimed at freeing political prisoners. The raids were repelled, with dozens of attackers and some police officerskilled. In reprisal, government forces and Portuguese vigilante groupsattacked Luanda’sslums, where they killed thousands of black civilian residents.

(Taken from Angolan War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

Background In the late 1400s, Portuguese merchant shipsestablished trading relations with the Kingdomof Congo in West Africa. Then in 1575, the Portuguese built a settlement inthe area of what is present-day Luanda (thePortuguese named the settlement São Pauloda Assumpção de Loanda), starting their involvement in the region thatbecame their future colony of Angola. During the next 300 years, the Portuguese founded more settlements, as well asfortifications, along the African Atlantic coast.

The Portuguese continued trading relations with the Kingdom of Congo, and built new trading ties withthe other tribal kingdoms in the area. They traded European firearms forthe natives’ ivory, minerals, and – of paramount importance in later periods –slaves. Slave trading in Luanda and otherPortuguese ports became important for Portugalin its development of its prized colony of Brazil,and for its huge profits in filling the big demand for manpower in other New World jurisdictions.

Portuguese settlements were situated along the coast, withfew settlers venturing into the African interior. Then in the 1880s,other European powers were jockeying aggressively to gain a share of the largecontinent, this so-called “Scramble for Africa” soon leading to Africabeing carved up into European colonies. As a result of many treatiessigned among the competing European powers, the borders of the African colonieswere fixed, with colonial rights for Angolabeing assigned to Portugal.

By the 1830s, Portugalhad lost Braziland had abolished its transatlantic slave trade. To replace these twovaluable sources of income, Portugalturned to develop its African possessions, including their interiorlands. In Angola,agriculture was developed, with the valuable export crops of coffee and cottonbeing grown in vast plantations. The mining industry was expanded.

Portugal’s development of the local economy, including theconstruction of public infrastructures such as roads and bridges, was carriedout using forced labor of black Africans, a system that was so harsh, ruthless,and akin to slavery. Consequently, thousands of natives fled from thecolony. Indigenous lands were seized by the colonial government. And while Angola’seconomy grew, only the colonizers benefited, while the overwhelming majority ofnatives were neglected and deprived of education, health care, and otherservices.

After World War II, thousands of Portuguese immigrants settledin Angola. The world’s prices of coffee beans were high, prompting the Portuguesegovernment to seek new white settlers in its African colonies to lead thegrowth of agriculture. However, many of the new arrivals settled in thetowns and cities, instead of braving the harsh rural frontiers. In urban areas,they competed for jobs with black Angolans who likewise were migrating there inlarge numbers in search of work. The Portuguese, being white, were givenemployment preference over the natives, producing racial tension.

The late 1940s saw the rapid growth of nationalism in Africa. In Angola, three nationalist movementsdeveloped, which were led by “assimilados”, i.e. the few natives who had acquired thePortuguese language, culture, education, and religion. The Portugueseofficially designated “assimilados” as “civilized”, in contrast to the vastmajority of natives who retained their indigenous lifestyles.

The first of these Angolan nationalist movements was thePeople’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola or MPLA(Portuguese: Movimento Popular deLibertação de Angola) led by local communists, and formed in 1956 from themerger of the Angolan Communist Party and another nationalist movement calledPLUA (English: Party of the UnitedStruggle for Africans in Angola). Active in Luanda and other major urban areas, the MPLAdrew its support from the local elite and in regions populated by the Ambunduethnic group. In its formative years, it received foreign support from otherleft-wing African nationalist groups that were also seeking the independencesof their colonies from European rule. Eventually, the MPLA fell under theinfluence of the Soviet Union and othercommunist countries.

The second Angolan nationalist movement was the NationalFront for the Liberation of Angola or FNLA(Portuguese: Frente Nacional deLibertação de Angola). The FNLA was formed in 1962 from the merger oftwo Bakongo regional movements that had as their secondary aim the resurgenceof the once powerful but currently moribund Kingdom of Congo. Primarily,the FNLA wanted to end forced labor, which had caused hundreds of thousands ofBakongo natives to leave their homes. The FNLA operated out ofLeopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) in the Congofrom where it received military and financial support from the Congolesegovernment. The FNLA was led by Holden Roberto, whose authoritarian rule and one-trackpolicies caused the movement to experience changing fortunes during the comingwar, and also bring about the formation of the third of Angola’s nationalist movements,UNITA.

UNITA or National Union for the Total Independence ofAngola (Portuguese: União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) was founded byJonas Savimbi, a former high-ranking official of the FNLA,over disagreements with Roberto. Unlike the FNLA and MPLA, which werebased in northern Angola,UNITA operated in the colony’s central and southern regions and gained its mainsupport from the Ovibundu people and other smaller ethnic groups. Initially, UNITA embraced Maoist socialism but later moved toward West-allieddemocratic Africanism.

February 2, 2022

February 2, 1981 – Paquisha War: Peru denounces Ecuador for the outbreak of fighting

On January22, 1981, a Peruvian transport helicopter was fired upon in the Comaina Valley, in a Peruvian-controlled areathat had been seized by Ecuadorian troops. Subsequently, Peruvian authorities discovered that the Ecuadorians hadconstructed three outposts in the Comaina Valley along the easternslope of the Condor. The Ecuadoriansnamed their outposts Mayaicu, Machinaza, and Paquisha, with the latter forwhich the coming war was named. In anOrganization of American States (OAS) foreign ministers meeting held onFebruary 2, 1981, the Peruvian representative denounced the Ecuadorianaction. Then in the next few days,Peruvian forces attacked the outposts, forcing the Ecuadorians to withdraw totheir side of the Condor Mountain Range. By February 5, Peruhad regained control of the whole Comaina Valley and also seizedEcuadorian military supplies and equipment that had been abandoned.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, producing tensions and wars between the two countries

(Taken from Paquisha War – Wars of the 20th Century- Vol. 2)

Background In July 1941, Ecuador and Peru (Map 38) fought a war forpossession of disputed territory located in the Amazon rainforest. After the war, both countries signed, inJanuary 29, 1942, the Rio Protocol (officially called the Protocol of Peace,Friendship, and Boundaries), which called for establishing the internationalborder between Ecuador and Peru. Four guarantor countries of the Rio Protocol,namely, the United States, Brazil, Argentina,and Chile,were tasked to under the border delineation process. Since much of the territory where the borderwould pass was thick Amazonian jungle, U.S. planes were brought in toundertake aerial surveys and thereby upgrade the existing Spanish colonial-eramaps of the region. Consequently, theMixed Border Commission, which was composed of technical teams from Ecuador, Peru, and the four guarantorcountries, succeeded in plotting much of the 1,600 kilometers of theEcuador-Peru border.

The U.S. aerial maps, released inFebruary 1947, showed an error in the technical descriptions used as the basisof the Rio Protocol in the watered areas adjoining the Condor Mountain Range (Spanish: Cordillera del Condor). In particular, the CenepaRiver, situated between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, was discovered tobe much more extensive than previously thought. As a result of the flaw, Ecuadorwanted to renegotiate the border along the 78-kilometer length of the CondorMountain Range, a proposal that was rejected by Peru. Furthermore, the U.S.maps showed two divortium aquariums,and not just one, between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, as indicated in Article VIII ofthe Rio Protocol, a discrepancy that eventually led the Ecuadorian governmentto declare that the Protocol, being flawed, was impossible to implement.

Two years earlier, in July 1945, whenthe length of the Cenepa River was yet undeterminedand only one divortium aquarium wasthought to exist in the Condor, the question of the placement of the border inthe Condor Mountain Range was brought before Brazilian Naval Captain Braz Diasde Aguiar. The multinational guarantorsof the Rio Protocol had tasked Captain Dias de Aguiar, atechnical expert, to mediate on the disputes that should arise. In his decision, Captain Dias de Aguiar,declared that the Condor Mountain Range was the border; this decision was acceptedby Ecuador and Peru.

As a result of the discrepancies inthe Rio Protocol revealed by the U.S. aerial maps, the Ecuadoriangovernment pulled out its representatives from the Mixed Border Commission inSeptember 1948, and withdrew altogether from the Demarcation Committee in1953. The demarcation of the border thenstopped, with all but 78 kilometers of the whole length left unsettled. In September 1960, Ecuador declared the Rio Protocolas null and void, stating that the Ecuadorian government during the 1941 war,had been forced under duress to accede to the Protocol, as Peruvian forces wereoccupying Ecuadorian territory at that time.

Consequently, no major diplomaticinitiatives were made to resolve the disputed border area. For the next several years, the heavilyforested region was unexplored and unsettled, although a few indigenous tribesresided there. The area soon becamemilitarized as Ecuador and Peru sent troops to stake claims, setting upbunkers and outposts, with the Ecuadorians positioned at the top and on thewestern slopes of the Condor Mountain Range and Peruvians along the easternslopes and adjacent Comaina Valley areas. Supplies to these army positions were sent byhelicopters, as the region practically did not have any roads.

February 1, 2022

February 1, 1979 – Iranian Revolution: Ayatollah Khomeini returns to Iran

On February 1, 1979, using a chartered Air France commercial plane, Ayatollah Khomeiniarrived in Tehranin triumph, with several millions of his supporters welcoming him and bringingthe whole country into frenzy. Immediately, he announced his rejection of the government of PrimeMinister Shapour Bakhtiar and on February 5, formed a “Provisional IslamicRevolutionary Government” led by his appointee, Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan,a moderate leftist non-cleric. Two rivalgovernments now existed, each denouncing the other, but with Bakhtiar’s regimehopelessly isolated and desertions rife, receiving virtually no popularsupport, and propped up only by the military.

Earlier on January 16, 1979, the Shah, his wife Queen Farah,and their family left Iranfor exile abroad, this decision also made at the urging of Prime MinisterBakhtiar in an effort to make reconciliation with the revolutionaries. The official reasons given for the departurewere for the Shah to take a “vacation” and for medical treatment. Celebrations broke out across the country,with millions pouring into the streets and destroying all remaining symbols ofthe monarchy. The Shah’s departure wasnot the end of the conflict, however, as the revolutionaries did not approve ofthe Bakhtiar regime, viewing the Prime Minister as another of the Shah’sfigureheads.

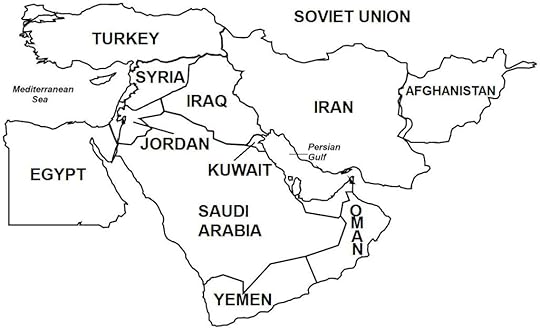

(Taken from Iranian Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

Background Underthe Shah, Iran developedclose political, military, and economic ties with the United States, was firmly West-aligned andanti-communist, and received military and economic aid, as well as purchasedvast amounts of weapons and military hardware from the United States. The Shah built a powerful military, at itspeak the fifth largest in the world, not only as a deterrent against the SovietUnion but just as important, as a counter against the Arab countries(particularly Iraq), Iran’s traditional rival for supremacy in the Persian Gulfregion. Local opposition and dissentwere stifled by SAVAK (Organization of Intelligence and National Security;Persian: Sāzemān-e Ettelā’āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar), Iran’s CIA-trained intelligence andsecurity agency that was ruthlessly effective and transformed the country intoa police state.

Iran, theworld’s fourth largest oil producer, achieved phenomenal economic growth in the1960s and 1970s and more particularly after the 1973 oil crisis when world oilprices jumped four-fold, generating huge profits for Iran that allowed its government toembark on massive infrastructure construction projects as well as socialprograms such as health care and education. And in a country where society was both strongly traditionalist andreligious (99% of the population is Muslim), the Shah led a government that wasboth secular and western-oriented, and implemented programs and policies thatsought to develop the country based on western technology and some aspects ofwestern culture. Iran’s push to westernize andsecularize would be major factors in the coming revolution. The initial signs of what ultimately became afull-blown uprising took place sometime in 1977.

At the core of the Shiite form of Islam in Iran is the ulama (Islamicscholars) led by ayatollahs (the top clerics) in a religious hierarchy thatincludes other orders of preachers, prayer leaders, and cleric authorities thatadministered the 9,000 mosques around the country. Traditionally, the ulama was apolitical anddid not interfere with state policies, but occasionally offered counsel or itsopinions on government matters and policies.

In January 1963, the Shah launched sweeping major social andeconomic reforms aimed at shedding off the country’s feudal, traditionalistculture and to modernize society. Theseambitious reforms, known as the “White Revolution”, included programs thatadvanced health care and education, and the labor and business sectors. The centerpiece of these reforms, however,was agrarian reform, where the government broke up the vast agriculturelandholdings owned by the landed few and distributed the divided parcels tolandless peasants who formed the great majority of the rural population. While land reform achieved some measure ofsuccess with about 50% of peasants acquiring land, the program failed to winover the rural population as the Shah intended; instead, the deeply religiouspeasants remained loyal to the clergy. Agrarian reform also antagonized the clergy, as most clerics belonged towealthy landowning families who now were deprived of their lands.

Much of the clergy did not openly oppose these reforms,except for some clerics in Qomled by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who in January 22, 1963 denounced the Shahfor implementing the White Revolution; this would mark the start of a longantagonism that would culminate in the clash between secularism and religionfifteen years later. The clerics alsoopposed other aspects of the White Revolution, including extending votingrights to women and allowing non-Muslims to hold government office, as well asbecause the reforms would reduce the cleric’s influence in education and familylaw. The Shah responded to AyatollahKhomeini’s attacks by rebuking the religious establishment as beingold-fashioned and inward-looking, which drew outrage from even moderateclerics. Then on June 3, 1963, AyatollahKhomeini launched personal attacks on the Shah, calling the latter “a wretched,miserable man” and likening the monarch to the “tyrant” Yazid I (an Islamic caliphof the 7th century). The governmentresponded two days later, on June 5, 1963, by arresting and jailing the cleric.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s arrest sparked strong protests thatdegenerated into riots in Tehran, Qom, Shiraz,and other cities. By the third day, theviolence had been quelled, but not before a disputed number of protesters werekilled, i.e. government cites 32 fatalities, the opposition gives 15,000, andother sources indicate hundreds.

Ayatollah Khomeini was released a few months later. Then on October 26, 1964, he again denouncedthe government, this time for the Iranian parliament’s recent approval of theso-called “Capitulation” Bill, which stipulated that U.S.military and civilian personnel in Iran, if charged with committingcriminal offenses, could not be prosecuted in Iranian courts. To Ayatollah Khomeini, the law was evidencethat the Shah and the Iranian government were subservient to the United States. The ayatollah again was arrested andimprisoned; government and military leaders deliberated on his fate, whichincluded execution (but rejected out of concerns that it might incite moreunrest), and finally decided to exile the cleric. In November 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini wasforced to leave the country; he eventually settled in Najaf, Iraq,where he lived for the next 14 years.

While in exile, the cleric refined his absolutist version ofthe Islamic concept of the “Wilayat al Faqih” (Guardianship of theJurisprudent), which stipulates that an Islamic country’s highest spiritual andpolitical authority must rest with the best-qualified member (jurisprudent) ofthe Shiite clergy, who imposes Sharia (Islamic) Law and ensures that statepolicies and decrees conform with this law. The cleric formerly had accepted the Shah and the monarchy in theoriginal concept of Wilayat al Faqih; later, however, he viewed all forms ofroyalty incompatible with Islamic rule. In fact, the ayatollah would later reject all other (European) forms ofgovernment, specifically citing democracy and communism, and famously declaredthat an Islamic government is “neither east nor west”.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s political vision of clerical rule wasdisseminated in religious circles and mosques throughout Iran from audio recordings thatwere smuggled into the country by his followers and which was tolerated orlargely ignored by Iranian government authorities. In the later years of his exile, however, thecleric had become somewhat forgotten in Iran, particularly among theyounger age groups.

January 31, 2022

January 31, 1943 – World War II: German Field Marshal Paulus surrenders to the Soviets at Stalingrad

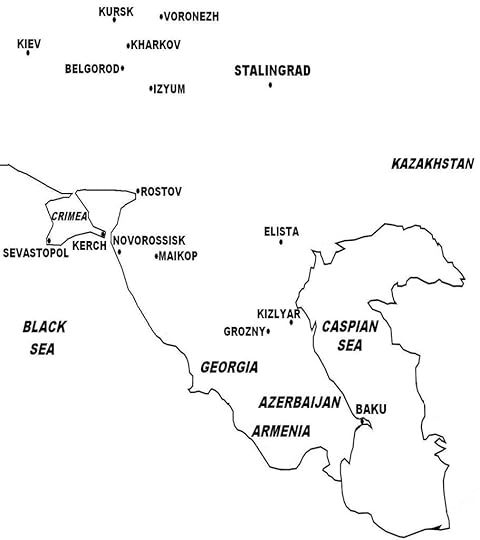

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, General Paulussurrendered to the Red Army, followed two days later by the remainder of histrapped forces, which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle ofStalingrad, one of the bloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axislosing 850,000 troops, 500 tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; andthe Soviets losing 1.1 million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces,and 2,800 planes. The German debacle atStalingrad and withdrawal from the Caucasuseffectively ended Case Blue, and like Operation Barbarossa in the previousyear, resulted in another German failure.

(Taken from Battle of Stalingrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Meanwhile to the north, German Army Group B, tasked withcapturing Stalingrad and securing the Volga, began its advance to the Don River on July 23, 1942. The German advance was stalled by fierceresistance, as the delays of the previous weeks had allowed the Soviets tofortify their defenses. By then, theGerman intent was clear to Stalin and the Soviet High Command, which thenreorganized Red Army forces in the Stalingradsector and rushed reinforcements to the defense of the Don. Not only was German Army Group B delayed bythe Soviets that had began to launch counter-attacks in the Axis’ northernflank (which were held by Italian and Hungarian armies), but also byover-extended supply lines and poor road conditions.

On August 10, 1942, German 6th Army had moved to the westbank of the Don, although strong Soviet resistance persisted in the north. On August 22, German forces establishedbridgeheads across the Don, which was crossed the next day, with panzers andmobile spearheads advancing across the remaining 36 miles of flat plains to Stalingrad. OnAugust 23, German 14th Panzer Division reached the VolgaRiver north of Stalingradand fought off Soviet counter-attacks, while the Luftwaffe began a bombingblitz of the city that would continue through to the height of the battle, whenmost of the buildings would be destroyed and the city turned to rubble.

On August 29, 1942, two Soviet armies (the 62nd and 64th)barely escaped being encircled by the German 4th Panzer Army and armored unitsof German 6th Army, both escaping to Stalingrad and ensuring that the battlefor the city would be long, bloody, and difficult.

On September 12, 1942, German forces entered Stalingrad, starting what would be a four-month longbattle. From mid-September to earlyNovember, the Germans, confident of victory, launched three major attacks tooverwhelm all resistance, which gradually pushed back the Soviets east towardthe banks of the Volga.

By contrast, the Soviets suffered from low morale, but werecompelled to fight, since they had no option to retreat beyond the Volga because of Stalin’s “Not one step back!”order. Stalin also (initially) refusedto allow civilians to be evacuated, stating that “soldiers fight better for analive city than for a dead one”. Hewould later allow civilian evacuation after being advised by his top generals.

Soviet artillery from across the Volgaand cross-river attempts to bring in Red Army reinforcements were suppressed bythe Luftwaffe, which controlled the sky over the battlefield. Even then, Soviet troops and suppliescontinued to reach Stalingrad, enough to keepup resistance. The ruins of the cityturned into a great defensive asset, as Soviet troops cleverly used the rubbleand battered buildings as concealed strong points, traps, and killingzones. To negate the Germans’ airsuperiority, Red Army units were ordered to keep the fighting lines close tothe Germans, to deter the Luftwaffe from attacking and inadvertently causingfriendly fire casualties to its own forces.

The battle for Stalingradturned into one of history’s fiercest, harshest, and bloodiest struggles forsurvival, the intense close-quarter combat being fought building-to-buildingand floor-to-floor, and in cellars and basements, and even in the sewers. Surprise encounters in such close distancessometimes turned into hand-to-hand combat using knives and bayonets.

By mid-November 1942, the Germans controlled 90% of thecity, and had pushed back the Soviets to a small pocket with four shallowbridgeheads some 200 yards from the Volga. By then, most of German 6th Army was lockedin combat in the city, while its outer flanks had become dangerouslyvulnerable, as they were protected only by the weak armies of its Axispartners, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians. Two weeks earlier, Hitler, believingStalingrad’s capture was assured, redeployed a large part of the Luftwaffe tothe fighting in North Africa.

Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months, the SovietHigh Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formations to the northand southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

The German High Command asked Hitler to allow the trappedforces to make a break out, which was refused. Also on many occasions, General Friedrich Paulus, commander of German6th Army, made similar appeals to Hitler, but was turned down. Instead, on November 24, 1942, Hitler advisedGeneral Paulus to hold his position at Stalingraduntil reinforcements could be sent or a new German offensive could break theencirclement. In the meantime, thetrapped forces would be supplied from the air. Hitler had been assured by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering that the 700tons/day required at Stalingrad could bedelivered with German transport planes. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to deliver the needed amount, despitethe addition of more transports for the operation, and the trapped forces in Stalingrad soon experienced dwindling supplies of food,medical supplies, and ammunition. Withthe onset of winter and the temperature dropping to –30°C (–22°F), anincreasing number of Axis troops, yet without adequate winter clothing,suffered from frostbite. At this timealso, the Soviet air force had began to achieve technological and combat paritywith the Luftwaffe, challenging it for control of the skies and shooting downincreasing numbers of German planes.

Meanwhile, the Red Army strengthened the cordon aroundStalingrad, and launched a series of attacks that slowly pushed the trappedforces to an ever-shrinking perimeter in an area just west of Stalingrad.

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked with securingthe gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch a reliefoperation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to breakout. Hitler and General Paulus bothrefused. General Paulus cited the lackof trucks and fuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, andthat his continued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Sovietforces which would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

Meanwhile in Stalingrad, byearly January 1943, the situation for the trapped German forces grewdesperate. On January 10, the Red Armylaunched a major attack to finally eliminate the Stalingradpocket after its demand to surrender was rejected by General Paulus. On January 25, the Soviets captured the lastGerman airfield at Stalingrad, and despite theLuftwaffe now resorting to air-dropping supplies, the trapped forces ran low onfood and ammunition.

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, on February 2,General Paulus surrendered to the Red Army, along with his trapped forces,which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle of Stalingrad, one of thebloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axis losing 850,000 troops, 500tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; and the Soviets losing 1.1million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 2,800 planes. The German debacle at Stalingrad andwithdrawal from the Caucasus effectively endedCase Blue, and like Operation Barbarossa in the previous year, resulted inanother German failure.

January 30, 2022

January 30, 1933 – Interwar Period: Hitler becomes Chancellor of Germany

In elections held in 1932, the Nazisbecame the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament), albeit withoutgaining a majority. Adolf Hitler longsought the post of German Chancellor, which was the head of government, but hewas rebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg[1],who distrusted Hitler. At this time,Hitler’s ambitions were not fully known, and following a political compromiseby rival parties, in January 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler asChancellor, with few Nazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power,and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

(Taken from Events leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 6)

Hitlerand Nazis in Power In October 1929, the severe economiccrisis known as the Great Depression began in the United States, and then spread outand affected many countries around the world. Germany, whoseeconomy was dependent on the United States for reparations payments andcorporate investments, was badly hit, and millions of workers lost their jobs,many banks closed down, and industrial production and foreign trade droppedconsiderably.

The Weimar government weakened politically, asmany Germans turned to radical ideologies, particularly Hitler’s ultra-rightwing nationalist Nazi Party, as well as the German Communist Party. In the 1930 federal elections, the Nazi Partymade spectacular gains and became a major political party with a platform ofimproving the economy, restoring political stability, and raising Germany’s international standing by dealing withthe “unjust” Versaillestreaty. Then in two elections held in1932, the Nazis became the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament),albeit without gaining a majority. Hitler long sought the post of German Chancellor, which was the head ofgovernment, but he was rebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg[2],who distrusted Hitler. At this time,Hitler’s ambitions were not fully known, and following a political compromiseby rival parties, in January 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler asChancellor, with few Nazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power,and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

On the night of February 27, 1933, firebroke out at the Reichstag, which led to the arrest and execution of a Dutcharsonist, a communist, who was found inside the building. The next day, Hitler announced that the firewas the signal for German communists to launch a nationwide revolution. On February 28, 1933, the German parliamentpassed the “Reichstag Fire Decree” whichrepealed civil liberties, including the right of assembly and freedom of thepress. Also rescinded was the writ ofhabeas corpus, allowing authorities to arrest any person without the need topress charges or a court order. In thenext few weeks, the police and Nazi SA paramilitary carried out a suppressioncampaign against communists (and other political enemies) across Germany,executing communist leaders, jailing tens of thousands of their members, andeffectively ending the German Communist Party. Then in March 1933, with the communists suppressed and other partiesintimidated, Hitler forced the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act,which allowed the government (i.e. Hitler) to enact laws, even those thatviolated the constitution, without the approval of parliament or thepresident. With nearly absolute power,the Nazis gained control of all aspects of the state. In July 1933, with the banning of politicalparties and coercion into closure of the others, the Nazi Party became the solelegal party, and Germanybecame de facto a one-party state.

At this time, Hitler grew increasinglyalarmed at the military power of the SA, particularly distrusting the politicalambitions of its leader, Ernst Rohm. On June 30-July 2, 1934, on Hitler’s orders,the loyalist Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel;English: Protection Squadron) and Gestapo (Secret Police) purged the SA,killing hundreds of its leaders including Rohm, and jailing thousands of itsmembers, violently bringing the SA organization (which had some three millionmembers) to its knees. The purgebenefited Hitler in two ways: First, he became the undisputed leader of theNazi apparatus, and Second and equally important, his standing greatlyincreased with the upper class, business and industrial elite, and Germanmilitary; the latter, numbering only 100,000 troops because of the Versaillestreaty restrictions, also felt threatened by the enormous size of the SA.

In early August 1934, with the death ofPresident Hindenburg, Hitler gained absolute power, as his Cabinet passed a lawthat abolished the presidency, and its powers were merged with those of thechancellor. Hitler thus became both German head of state and headof government, with the dual roles of Fuhrer (leader) and Chancellor. As head of state, he also was SupremeCommander of the armed forces, making him absolute ruler and dictator of Germany.

In domestic matters, the Nazi governmentmade great gains, improving the economy and industrial production, reducingunemployment, embarking on ambitious infrastructure projects, and restoringpolitical and social order. As a result,the Nazis became extremely popular, and party membership grew enormously. This success was brought about from soundpolicies as well as through threat and intimidation, e.g. labor unions and jobactions were suppressed.

Hitler also began to impose Nazi racialpolicies, which saw ethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising“super-humans” (Ubermensch),while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered“sub-humans” (Untermenschen);also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-based groups, i.e. communists,liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah’sWitnesses, etc. Nazi lebensraum (“livingspace”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russia called for eliminating theSlavic and other populations there and replacing them with German farm settlersto help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-year German Empire.

In Germanyitself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws inSeptember 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the local Jews,stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment and education,revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and social life,disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring themundesirables in Germany. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews left Germany. Hitler blamed the Jews (and communists) forthe civilian and workers’ unrest and revolution near the end of World War I,ostensibly that had led to Germany’sdefeat, and for the many social and economic problems currently afflicting thenation. Following anti-Nazi boycotts inthe United States, Britain, and other countries, Hitler retaliatedwith a call to boycott Jewish businesses in Germany, which degenerated intoviolent riots by SA mobs that attacked and killed, and jailed hundreds of Jews,looted and destroyed Jewish properties, and seized Jewish assets. The most notorious of these attacks occurredin November 1938 in “Kristallnacht”(Crystal Night), where in response to the assassination of a German diplomat bya Polish Jew in Paris, the Nazi SA and civilian mobs in Germany went on aviolent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews, jailing tens of thousands of others,and looting and destroying Jewish homes, schools, synagogues, hospitals, andother buildings. Some 1,000 synagogueswere burned, and 7,000 businesses destroyed.

In foreign affairs, Hitler, like mostGermans, denounced the Versaillestreaty, and wanted it rescinded. In1933, Hitler withdrew Germanyfrom the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva,and in October of that year, from the League of Nations, in both casesdenouncing why Germanywas not allowed to re-arm to the level of the other major powers.

In March 1935, Hitler announced thatGerman military strength would be increased to 550,000 troops, militaryconscription would be introduced, and an air force built, which essentiallymeant repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles and the start of full-scalerearmament. In response, Britain, France,and Italyformed the Stresa Front meant to stop further German violations, but thisalliance quickly broke down because the three parties disagreed on how to dealwith Hitler.

Italy,after being denounced by the League of Nations and slapped with economic sanctions after itsinvasion of Ethiopia,switched sides to Germany. Mussolini and Hitler signed a series ofagreements that soon led to a military alliance. Meanwhile, Britainand France continued theirindecisive foreign policies toward Germany. In March 1936, in a bold move, Hitler senttroops to the Rhineland, remilitarizing the region in another violation of the Versailles treaty, but metno hostile response from the other powers. Hitler justified this move as a defensive response to the recentlyconcluded French-Soviet mutual assistance pact, which he accused the twocountries of encircling Germany,a statement that drew sympathy from some British politicians.

Nazi ideology called for unification ofall Germanic peoples into a Greater German Reich. In this context, Hitler had long sought toannex Austria, whose indigenouspopulation was German, into Germany. An annexation attempt in 1934 was foiled byItalian intervention, with Mussolini determined to go to war if Germany invaded Austria. But by 1938, German-Italian relations hadwarmed and were moving toward a military alliance. With Britainand France watching by, inMarch 1938, Hitler put political pressure on Austria, and with the threat ofinvasion, forced the Austrian government to resign, and cede power to theAustrian Nazi Party. Within days, thelatter relinquished Austrian independence to Germany,and German troops occupied Austria. In a Nazi-controlled plebiscite held in April1938, an improbable 99.7% of Austrians voted for “Anschluss”(political union) with Germany.

In late March 1938, while Germany wasyet in the process of annexing Austria, another conflict, the “SudetenlandCrisis” occurred,where ethnic Germans, who formed the majority population in the Sudeten regionof Czechoslovakia, demanded autonomy and the right to join the Nazi Party. Hitler supported these demands, citing theSudeten Germans’ right to self-determination. The Czechoslovak government refused, and in May 1938, mobilized for war.In response, Hitler secretly asked the German High Command to prepare for war,to be launched in October 1938. Britain and France,anxious to avoid war at all costs by not antagonizing Hitler (a policy calledappeasement), pressed Czechoslovakiato yield, with the British even stating that the Sudeten Germans’ demand forautonomy was reasonable. In earlySeptember 1938, the Czechoslovak government agreed to the demands. Then when civilian unrest broke out in theSudetenland which the Czechoslovakian police quelled, in mid-September 1938, afurious Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland be ceded to Germany in order to stop thesupposed slaughter of Sudeten Germans. Under great pressure from Britainand France, on September 21,1938, the Czechoslovak government relented, and agreed to cede the Sudetenland. Butthe next day, Hitler made new demands, which Czechoslovakia rejected and againmobilized for war. In a frantic move toavert war, the Prime Ministers of Britainand France, NevilleChamberlain and Edouard Daladier, respectively, togetherwith Mussolini, met with Hitler, and on September 29, 1938, the four men signedthe Munich Pact,where the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany. Two days later, Czechoslovakiaaccepted the fait accompli, knowingit would not be supported by Britainand France in a war with Germany. In succeeding months, Czechoslovakia disintegrated as a sovereignstate: the Slovak region separated, aligning with Germanyas a puppet state; other regions were annexed by Hungaryand Poland; and in March1939, the rest of the Czech portion of the country was occupied by Germany.

Hitler then turned to Poland, and proposed to renew their ten-yearnon-aggression pact (signed in 1934) in exchange for revising their commonborder, specifically returning to Germanysome territories that were ceded to Poland after World War I. The Polish government refused, causing Hitlerto rescind the pact in April 1939. Bythen, Britain and France had abandoned appeasement in favor ofassertive diplomacy, and promised military support to Poland if Germany invaded. In the period May-August 1939, as war loomed,frantic efforts were made by Britainand France jointly, and by Germany, to win over to their side the lastremaining undecided major European power, the Soviet Union. The Germans prevailed, and a non-aggressionpact was signed with the Soviets on August 23, 1939, which prompted Hitler tobegin hostilities with Polandunder the mistaken belief that Britainand Francewould not react militarily.

[1] Hindenburg achieved worldwide fame in World War I as Germany’sChief of the General Staff

[2] Hindenburg achieved worldwide fame in World War I as Germany’sChief of the General Staff

January 29, 2022

January 29, 1942 – Ecuadorian-Peruvian War: The Rio Protocol is signed, ending war

Peace talks were held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. On January 29, 1942, Ecuador and Peru signed the Rio Protocol, anagreement where the two countries promised to cooperate to establish a commonborder. Also under the agreement, Ecuadorrenounced its claim of ownership to the disputed territories. In return, Peru withdrew its forces fromEcuadorian territories that were captured in the war.

A team of technical experts from the United States, Brazil,Argentina, and Chilearrived to delineate the border. Sincemuch of the territory where the border would pass was Amazonian jungle, U.S.Air Force planes conducted aerial surveys. The resulting maps that were produced showed some discrepancies betweenthe actual topography and the territorial descriptions found in the RioProtocol. Ecuador asked to renegotiate theborder, and subsequently withdrew from the demarcation panel, leaving the borderincompletely demarcated. Ecuadorhad declared that the Rio Protocol, with its flawed technical descriptions inthe Condor-Cenepa region, was impossible to carry out, and that it had beenforced to sign the Rio Protocol because Peruvian troops were occupying portionsof Ecuadorian territory. As a result ofthe impasse, Ecuador and Peruwould fight two more wars later in the twentieth century.

(Taken from Ecuadorian-Peruvian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

Background In1941, war broke out between Ecuadorand Peru for possession ofthe Amazonian regions of Maynas and Jaen,as well as Tumbez. The war has itsorigin dating from the last century, when both countries gained theirindependence from Spain,i.e. Ecuador as a province of GranColombia (in 1817), and Peruas a sovereign state (in 1821).

Gran Colombiaand Peru,respectively, were formed from the Spanish territories of the Viceroyalty ofNew Granada and the Viceroyalty of Peru. These viceroyalties shared a border that was imprecisely defined inMaynas and Jaen,or had regions transferred between them, as in Tumbez. After gaining independence, Gran Colombia and Peruinherited these imprecise borders and the undelineated regions of Maynas, Jaen, and Tumbez.

Precisely as a result of their undefined border, Gran Colombia and Peru went to war in 1828. The war was inconclusive in the disputedregions, and the two countries agreed to maintain the territorial statusquo. In 1830, Gran Colombia was dissolved and replaced by three newcountries: Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The disputed lands now lay between Ecuador and Peru. The two countries met a number of times toresolve the issue and work out a common border. These negotiations failed, however, as the two sides held colonial-eradocuments that claimed ownership to the lands. Then in 1857, Ecuadortried to trade off a section of the disputed territories to pay off its foreigndebt. Peru used military force to stopthe transaction from taking place.

By the early 1900s, Peruhad gained control of Tumbez and Jaen,and most of Maynas. In 1933, Peru had its claim strengthened after fighting aborder war with Colombia. Negotiations after the war fixed theColombia-Peru border. Colombia also recognized Peru’s sovereignty over Tumbez, Jaen, and Maynas.

In 1936, Peruand Ecuadorsigned the Lima Accord, where the two countries agreed to respect each other’scontrol of occupied lands inside the disputed territories. Within two years of the agreement, however,skirmishes were taking place in the region.

January 28, 2022

January 28, 1995 – Cenepa War: Peruvian forces attack Ecuadorian outposts

Both countries mobilized for war,massing their main forces along the border near the Pacific coast. The war was confined to the Condor-Ceneparegion, however, where the Peruvians launched many offensives aimed atdestroying the Ecuadorian positions located at the eastern slope of theCondor. On January 28, 1995, Peruvianground forces, later backed by air cover, launched successive attempts on theEcuadorian outposts. The ground attacksinvolved an uphill climb against well-entrenched positions. More attacks were carried out the next dayand into early February, with the Peruvians attempting to outflank the outpostsbut being met by strong resistance. OnFebruary 1, a Peruvian advance on Cuevas de los Tayos fell into a minefield,causing several casualties.

(Taken from Cenepa War – Wars of the 20th Century- Vol. 2)

Background The 1981 Paquisha War (previous article) between Ecuador and Peruleft unsettled the border dispute regarding sovereignty over the Condor Mountainrange and the Cenepa River system locatedinside the Amazon rainforest. Peruvianforces achieved a tactical victory by destroying three Ecuadorian forwardoutposts and re-established control over the whole eastern side of the Condorrange, although the Ecuadorian government continued to claim ownership over thewhole Condor-Cenepa region. In the yearsfollowing the Paquisha War, the two sides strengthened their areas of controlin the region, with the Ecuadorians occupying the peaks and western slope ofthe Condor range, and the Peruvians at the Condor’s eastern slope and Cenepa Valley. Because of the thick forest cover, Ecuadorianand Peruvian patrols often accidentally encountered each other, which at thevery worst, led to exchanges of gunfire, but generally ended without incident,as the two sides had agreed to abide by the Cartillas de Seguridad yConfianza (Guidelines for Security and Trust), which lay down the rules to prevent unnecessary bloodshed.

In November 1994, a Peruvian armypatrol came upon an enemy outpost and was told by the Ecuadorian commanderthere that the location was situated inside the Ecuadorian Army’s area ofcontrol. The Peruvian Army soon learnedthat the outpost, which the Ecuadorians named “Base Sur”, was located on theeastern slope of the Condor, and therefore in the area traditionally underPeruvian control. Thereafter, theEcuadorian and Peruvian local commanders met a number of times to try and workout a resolution, but nothing came out of the meetings.

With tensions rising by December 1994,Ecuador and Peru began sending reinforcements and large quantities of weaponsand military equipment to the disputed zone, a difficult and hazardousoperation (particularly for Peru’s Armed Forces because of the greaterdistance) which required air transports because of the absence of roads leadingto the Condor region.

Apart from “Base Sur”, the Ecuadorianshad set up a number of other outposts, including “Tiwintza” and “Cueva de losTayos”, and the larger “Coangos”, near the top of the Condor Mountain. The camps’ defenses were strengthened by newminefields laid out at the approaches, and the installation of anti-aircraftbatteries and multiple-rocket launchers; a further boost was provided by thearrival of Ecuadorian Special Forces and specialized teams equipped withhand-held surface-to-air missile launchers to be used against Peruvian planes.

By early January 1995, the strongPeruvian presence was being felt with an increase in military activities nearthe Ecuadorian forward outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols encountered each other on January 9 andJanuary 11, with the latter encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire. Then on January 21, Peruvian troops werelanded by helicopter behind the Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for aPeruvian full offensive. Theinfiltration was discovered when an Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruviansoldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in; after a two days’ trek throughthe jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian camp. In the ensuing firefight, the Ecuadoriansdispersed the Peruvians. A number ofPeruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in the campwere seized.