Daniel Orr's Blog, page 38

January 15, 2022

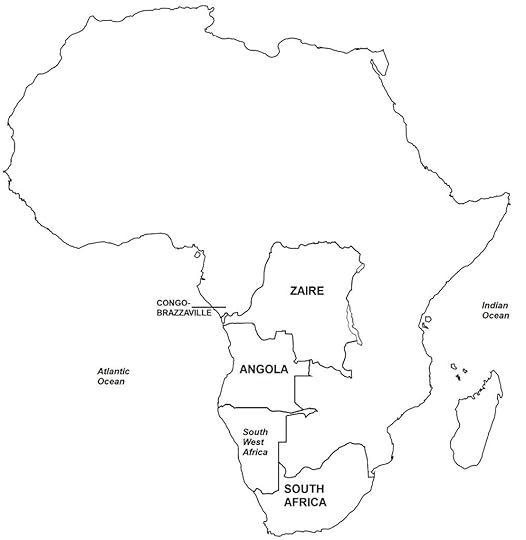

January 15, 1975 – Angolan War of Independence: Portugal and Angolan rebels sign the Alvor Agreement that grants independence of Angola

In January 1975, the Portuguese government met with theleaders of the three Angolan nationalist movements in a series of negotiationsin Alvor, Portugal. These negotiations resulted in the signing ofthe Alvor Agreement on January 15, 1975, which contained severalprovisions. First, Angola’s independence was set forNovember 11, 1975. Second, during theten-month interim period before independence, the three nationalist movementswould form a power-sharing government to lead the country, with the localPortuguese High Commissioner acting as the mediator for disputes. Third, a national constitution would bedrafted, and parliamentary elections would be held in October 1975. Fourth, the nationalist groups’ armed wingswould be integrated into the Portuguese colonial army; after the Portuguese hadwithdrawn from Angola, thecore of Angola’sArmed Forces would have been formed.

Consequently, the Angolan nationalists formed a coalitiongovernment which, however, proved ineffective and barely functioned. Furthermore, none of the other provisions ofthe Alvor Agreement was truly implemented. And just as the Alvor Agreement ended Portugal’swar in Angola, it alsosparked the so-called “decolonization war” (the hostilities during the interimperiod before Angola’sindependence) among the three Angolan nationalist movements, particularlybetween FNLA and MPLA. Shortly after Portugal had set the date for Angola’s independence, the Angolannationalist movements began aggressive recruitment campaigns and sought moreweapons deliveries from their foreign backers.

(Taken from Angolan War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 1)

Background By the1830s, Portugal had lost Braziland had abolished its transatlantic slave trade. To replace these two valuable sources ofincome, Portugalturned to develop its African possessions, including their interior lands. In Angola, agriculture was developed,with the valuable export crops of coffee and cotton being grown in vastplantations. The mining industry wasexpanded.

Portugal’s development of the local economy, including theconstruction of public infrastructures such as roads and bridges, was carriedout using forced labor of black Africans, a system that was so harsh, ruthless,and akin to slavery. Consequently,thousands of natives fled from the colony. Indigenous lands were seized by the colonial government. And while Angola’s economy grew, only thecolonizers benefited, while the overwhelming majority of natives were neglectedand deprived of education, health care, and other services.

After World War II, thousands of Portuguese immigrantssettled in Angola. The world’s prices of coffee beans were high,prompting the Portuguese government to seek new white settlers in its Africancolonies to lead the growth of agriculture. However, many of the new arrivals settled in the towns and cities,instead of braving the harsh rural frontiers. In urban areas, they competed forjobs with black Angolans who likewise were migrating there in large numbers insearch of work. The Portuguese, beingwhite, were given employment preference over the natives, producing racialtension.

The late 1940s saw the rapid growth of nationalism in Africa. In Angola,three nationalist movements developed, which were led by “assimilados”, i.e.the few natives who had acquired the Portuguese language, culture, education,and religion. The Portuguese officiallydesignated “assimilados” as “civilized”, in contrast to the vast majority ofnatives who retained their indigenous lifestyles.

The first of these Angolan nationalist movements was thePeople’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola or MPLA (Portuguese: MovimentoPopular de Libertação de Angola)led by local communists, and formed in 1956 from the merger of the AngolanCommunist Party and another nationalist movement called PLUA (English: Party ofthe United Struggle for Africans in Angola). Active in Luanda and other major urban areas, the MPLAdrew its support from the local elite and in regions populated by the Ambunduethnic group. In its formative years, itreceived foreign support from other left-wing African nationalist groups thatwere also seeking the independences of their colonies from European rule. Eventually, the MPLA fell under the influenceof the Soviet Union and other communistcountries.

The second Angolan nationalist movement was the NationalFront for the Liberation of Angola or FNLA (Portuguese: Frente Nacional deLibertação de Angola). The FNLA was formed in 1962 from the mergerof two Bakongo regional movements that had as their secondary aim theresurgence of the once powerful but currently moribund Kingdom of Congo. Primarily, the FNLA wanted to end forcedlabor, which had caused hundreds of thousands of Bakongo natives to leave theirhomes. The FNLA operated out ofLeopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) in the Congofrom where it received military and financial support from the Congolesegovernment. The FNLA was led by HoldenRoberto, whose authoritarian rule and one-track policies caused the movement toexperience changing fortunes during the coming war, and also bring about theformation of the third of Angola’snationalist movements, UNITA.

UNITA or National Union for the Total Independence of Angola(Portuguese: União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) was foundedby Jonas Savimbi, a former high-ranking official of the FNLA, overdisagreements with Roberto. Unlike theFNLA and MPLA, which were based in northern Angola, UNITA operated in thecolony’s central and southern regions and gained its main support from theOvibundu people and other smaller ethnic groups. Initially, UNITA embraced Maoist socialismbut later moved toward West-allied democratic Africanism.

January 14, 2022

January 14, 1943 – World War II: The Western Allies hold the Casablanca Conference

On January 14, 1943, the United States and Great Britain held the CasablancaConference to discuss planning and strategy, particularly for the ongoingEuropean theatre of World War II. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt andBritish Prime Minister Winston Churchill led the delegations of theirrespective countries. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin declined to attend, statingthat the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad required his presence in the Soviet Union. A delegation of the Free French forces alsoattended, led by Generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud. The conferenceproduced the Casablanca Declaration, which contained the stipulation that theAllies would accept nothing short of the “unconditional surrender” of Germany and Japan.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

“Big Three” AlliedWar Conferences The United States, Britain,and Soviet Union, the so-called “Big Three” Powers, met in two major war-timeconferences, at Tehran (November 28 – December1, 1944) and Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and inthe immediate post-war period, at Potsdam(July 17-August 2, 1945). At the Tehran (Iran)Conference, the Big Three agreed to align military strategy. At the Yalta Conference (Yalta,Crimea, USSR)which was attended by U.S. President Roosevelt, British Prime MinisterChurchill, and Soviet leader Stalin, the Allies, now in an overwhelmingmilitary position, agreed on the disposition of post-war Germany and Europe. By then, Stalin was negotiating in a superiorposition, as his Red Army was only 40 miles (65 km) from Berlin. Stalin agreed to join the war in the Asia-Pacific against Japan, andbecome a member of the United Nations (both requested by the United States),but in return persuaded Roosevelt and Churchill to allow the following: thatthe Soviet-Polish border be moved to the Curzon Line, that the Soviets gain theSouth Sakhalin and Kuril Islands from Japan, that the Port Arthur lease berestored to the Soviets, and that Mongolia (a Soviet satellite polity since1924) been detached from China.

Of major contention at Yalta was the issue of Poland, asRoosevelt and Churchill wanted to return the Polish government-in-exile (inLondon) to power, while Stalin insisted on installing the pro-Soviet governmentalready operating in recaptured Polish territories In fact, Poland formed only part of thelarger issue regarding the political future of Eastern Europe, where Stalinwanted to impose a Soviet sphere of influence to safeguard against anotherinvasion from the West, while Roosevelt and Churchill wanted democraticgovernments to be established there. Instead, the Big Three signed the “Declaration of Liberated Europe”,where they agreed that European nations must be allowed “to create democraticinstitutions of their own choice” and to “the earliest possible establishmentthrough free elections [of] governments responsive to the will of thepeople”. Free elections were to beconducted in Polandas well, and the Soviet-sponsored provisional government, while remainingpredominant, would be encouraged to include non-communists “on a broaddemocratic basis”.

In the Potsdam agreement, the “Big Three”, now led by U.S.President Harry Truman (succeeding Roosevelt), British Prime Minister ClementAtlee (succeeding Churchill), and Stalin reaffirmed previous agreements withregards to dealing with post-war Germany and the territorial changes demandedby Stalin. As well, Germany was required to pay warreparations, and ethnic Germans were to be expelled from the former Germanlands and forced to move to within the new German borders. As Soviet domination of Poland was now a fait accompli, theWestern Allies acquiesce to the authority of the pro-Soviet Polish governmentin that country.

January 13, 2022

January 13, 1920 – Latvian War of Independence: Soviet Russia ceases its support for the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic

The final combat phase ofLatvia’sindependence war occurred on January 3, 1920 when the combined Latvian andPolish Armies attacked and captured Latgale, freeing the last Latvian territorystill held by the Red Army. Then afterachieving another decisive victory at the Battle of Daugavpils (fought under harsh, sub-zerowinter conditions), the Latvian-Polish forces pushed the Red Army into Russianterritory. Polish forces then withdrewfrom Latgale after turning over the territory to the Latvians. The Russian government ceased its support forthe Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, whichdisbanded on January 13, 1920.

(Taken from Latvian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

Background As aresult of the Northern Crusades in the 13th century, the variousindigenous peoples inhabiting the eastern Baltic region (which includes thelands that comprise present-day Latvia)were converted to Christianity. Germancrusader-knights of the Teutonic Order founded Riga(the present-day capital of Latvia)from where they conquered the adjacent regions, including the territory to thenorth that now constitutes modern-day Estonia. German settlers then arrived and settled inthe regions, and Riga was transformed during themedieval period into a major center of the Hanseatic League, which was an economic and trade alliance of many major cities along thecoasts of the North and Baltic Seas. As a result of these invasions, the ethnicGerman conquerors gained political, economic, and social ascendancy in Latvia(which largely would persist for the next 700 years) by acquiring vast tractsof land that were converted to feudal agricultural manorial estates worked byethnic Latvians who were relegated to the status of peasant laborers.

In 1561, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, aconfederated empire of two sovereign states, gained control of large portionsof Latvian territory, which in turn, after the Polish-Swedish War ended in 1629, it ceded to theSwedish Empire. In 1721, the SwedishEmpire, following its defeat in the Northern Wars, yielded the territory to the victorious and emerging RussianEmpire. In the Polish-Lithuanian,Swedish, and Russian conquests, the local German authority in Latvia, now forming the “BalticGerman nobility”, was allowed to maintain local rule on behalf of the greatercolonial power. Latvia under Tsarist Russia was ruled under twojurisdictions: the Governorate (province) of Courlandon the west and Governorate of Livonia. The latter comprised the ethnic Estonian northern region and the ethnicLatvian southern region – upon the independence of Estonia and Latvia, theGovernorate of Livonia’s Estonian north became part of Estonia while theLatvian south merged with the Governorate of Courland to form the Latvian state(Figure 20).

By the mid-19thcentury, as a result of the French Revolution (1789-1799), a wave ofnationalism swept across Europe, a phenomenon that touched into Latvia aswell. The Latvian nationalist movementwas led by the “Young Latvians”, a nationalist movement of the 1850s to 1880sthat promoted Latvian identity and consciousness (as opposed to the prevailingGermanic viewpoint that predominated society) expressed in Latvian art,culture, language, and writing. TheBaltic German nobility used its political and economic domination of society tosuppress this emerging Latvian nationalistic sentiment. The Russian government’s attempt at“Russification”(cultural and linguistic assimilation into the Russian state) was rejected byLatvians. The Latvian national identityalso was accelerated by other factors: the abolition of serfdom in Courland in1817 and Livoniain 1819, the growth of industrialization and workers’ organizations, increasingprosperity among Latvians who had acquired lands, and the formation of Latvianpolitical movements.

The Russian Empireopposed these nationalist sentiments and enforced measures to suppressthem. Then in January 1905, the socialand political unrest that gripped Russia(the Russian Revolution of 1905) produced major reverberations in Latvia, starting in January 1905, when massprotests in Rigawere met with Russian soldiers opening fire on the demonstrators, killing andwounding scores of people. Localsubversive elements took advantage of the revolutionary atmosphere to carry outa reign of terror in the countryside, particularly targeting the Baltic Germannobility, torching houses and looting properties, and inciting peasants to riseup against the ethnic German landowners. In November 1905, Russian authorities declared martial law and broughtin security forces that violently quelled the uprising, executing over 1,000dissidents and sending thousands of others into exile in Siberia.

Then in July 1914, WorldWar I broke out in Europe, with Russiaallied with other major powers Britainand France as the TripleEntente, against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire that comprised the major Central Powers. In 1915, the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary made military gainsin the northern sector of the Eastern Front; by May of that year, German unitshad seized sections of Latvian Courland and Livonian Governorates. A tenacious defense put up by the newlyformed Latvian Riflemen of the Imperial Russian Army held off the Germanadvance into Rigafor two years, but the capital finally fell in September 1917.

Meanwhile, by 1917, theRussian Empire was verging on a major political collapse at home afterexperiencing a number of devastating military defeats in the Eastern Front ofthe war,. Two revolutions broke out thatyear. The first, on March 8 (this daybeing February 23 in the Julian calendar that was used in Russia at that time,hence the historical name, “February Revolution” denoting the event; in January1918, Russia, by now ruled by the Bolsheviks, adopted the Gregorian calendarthat was already in use in Western Europe), led to the end of three centuriesof Romanov dynastic rule in Russia with the abdication of Tsar NicholasII. A Russian Provisional Government wasinstalled to administer the country which it declared as the “Russian Republic”.

The second revolution of1917 occurred on November 7 (October 25 in the Julian calendar, thus thepopular name “October Revolution” denoting this event), where the communistBolshevik Party came to power by overthrowing the Russian ProvisionalGovernment in Petrograd, Russia’s capital. The two 1917 revolutions, as well as ongoing events in World War I,catalyzed ethnic minorities across the Russia Empire, resulting in the variousregional nationalist movements pushing forward their political objectives ofseceding from Russiaand forming new nation-states. In thewestern and northern regions of the empire, the subject territories of Poland, Belarus,Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia,Estonia, and Finland moved toward secession from Russia.

Imperial Russian governorates of Estonia, Livonia, and Courland

Imperial Russian governorates of Estonia, Livonia, and CourlandThe Bolsheviks, on comingto power in the October Revolution, issued the “Declarationof the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” (on November 15, 1917), which grantedall non-Russian peoples of the former Russian Empire the right to secede fromRussia and establish their own separate states.Eventually, the Bolsheviks would renege on this edict and suppress secessionfrom the Russian state (now known as Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic,or RSFSR). The Bolshevik revolution alsohad succeeded partly on the communists promising a war-weary citizenry that Russiawould withdraw from World War I; thereafter, the Russian government declaredits pacifist intentions to the Central Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talksbegan a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest,in Belarus).

However, the CentralPowers imposed territorial demands that the Russian government deemedexcessive. On February 17, 1918, theCentral Powers repudiated the ceasefire agreement, and the following day, Germany and Austria-Hungaryrestarted hostilities, launching a massive offensive with one million troops in53 divisions along three fronts that swept through western Russia and captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia,and Estonia. German forces also entered Finland, assisting thenon-socialist paramilitary group known as the “White Guards” in defeating thesocialist militia known as “Red Guards” in the Finnish Civil War. Eleven days into the offensive, the northernfront of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capital of Petrograd.

On February 23, 1918, orfive days into the offensive, peace talks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, withthe Central Powers demanding even greater territorial and military concessionson Russia than in the December 1917 negotiations. After heated debates among members of theCouncil of People’s Commissars (the highest Russian governmental body) who wereundecided whether to continue or end the war, at the urging of its Chairman,Vladimir Lenin, the Russian government acquiesced to the Treaty ofBrest-Litovsk. On March 3, 1918, Russianand Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whose major stipulationsincluded the following: peace was restored between Russia and the CentralPowers; Russia relinquished possession of Finland (which was engaged in a civilwar), Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic territories of Estonia, Latvia, andLithuania – Germany and Austria-Hungary were to determine the future of theseterritories; and Russia also agreed on some territorial concessions to theOttoman Empire.

German forces occupied Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine,and Poland,establishing semi-autonomous governments in these territories that weresubordinate to the authority of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German occupation of the region allowedthe realization of the Germanic vision of “Mitteleuropa”, an expansionist ambition aimed at unifying all Germanic andnon-Germanic peoples of Central Europe into agreatly enlarged and powerful German Empire. In support of Mitteleuropa, in the Baltic region, the Baltic Germannobility proposed to set up the United Baltic Duchy, a semi-autonomouspolitical entity consisting of present-day Latviaand Estoniathat would be voluntarily integrated into the German Empire. The proposal was not implemented, but Germanmilitary authorities set up local civil governments under the authority of theBaltic German nobility or ethnic Germans.

January 12, 2022

January 12, 1964 – Zanzibar Revolution: Rebels overthrow the ruling monarchy and establish a socialist government

On January 12, 1964, in Zanzibar’smain island of Unguja, hundreds of fanaticalfighters belonging to the Afro-Shirazi Youth led by John Okello, attacked policestations and seized armories outside Zanzibar’scapital of Stone Town. Now possessing firearms, the rebels proceededto Stone Town, where they overwhelmed more policeunits and took control of government buildings, public utilities, and thecity’s radio station. Within a fewhours, the rebellion had gained the support of the vast majority of the generalpopulation. Scores of local civilianstook up arms and joined the rebels in defeating the remaining governmentforces. Just nine hours after theuprising began, the rebels had gained full control of the capital. Zanzibar’sgovernment collapsed, and the sultan and his Cabinet fled into exile abroad.

(Taken from Zanzibar Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

Background In July 1963, legislative elections in Zanzibar had given theArab Zanzibari political coalition, led by the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP),a majority in parliament. The mainopposition party, the black African-dominated Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) had won fewer seats in the elections,despite garnering 54% of the popular vote. The ASP had accused the government of carrying out electoral fraud toensure the ZNP’s victory. As a result,violence broke out that caused a number of civilian deaths.

Zanzibari society was religiously homogenous, with99% of the population belonging to the Islamic faith. The country had three major ethnic groups:black Africans and mixed African-Persians (called Shirazi), both groups numbering230,000 persons andcomprising 76% of the population; ethnic Arabs at 50,000 or 17% of thepopulation, and ethnic Indians at 20,000 or 6% of the population.

Africa showing location of Zanzibar

Africa showing location of ZanzibarTraditionally, Zanzibarwas stratified into three economic groups: ethnic Arabs, who owned vast tractsof agricultural lands; ethnic Indians, who dominated the business sector as tradersand merchants; and the indigenous Africans, who comprised the great majority ofthe laborers and farm workers. However,many exceptions had developed over time, e.g. the majority of new Arabimmigrants to Zanzibarwere poor, and some black Zanzibaris became wealthy landowners.

A few weeks after Zanzibar gained its independence, rumorsarose that the outlawed communist Umma Party was planning to overthrow the government andwas secretly bringing in weapons to the island. The Zanzibari sultan asked Britainfor military assistance, but the British government, which had alreadywithdrawn British troops from Zanzibar,denied the request. Zanzibar’s defense thus was left to theisland’s small police force.

Revolution Early in the morning of January 12, 1964, in Zanzibar’s main islandof Unguja (also more commonly called Zanzibar,Map 20), hundreds of fanatical fighters belonging to the Afro-Shirazi Youth led by John Okello, attacked policestations and seized armories outside Zanzibar’scapital of Stone Town. Now possessing firearms, the rebels proceededto Stone Town, where they overwhelmed more policeunits and took control of government buildings, public utilities, and thecity’s radio station. Within a fewhours, the rebellion had gained the support of the vast majority of the generalpopulation. Scores of local civilianstook up arms and joined the rebels in defeating the remaining governmentforces. Just nine hours after theuprising began, the rebels had gained full control of the capital. Zanzibar’sgovernment collapsed, and the sultan and his Cabinet fled into exile abroad.

Okello called on the ASP’s leader, Abeid Karume, to form a newgovernment. The ASP and the Umma Partyformed a ruling revolutionary council that was led by Karume, who also became Zanzibar’s firstpresident. Karume’s government renamedthe country the “People’s Republic of Zanzibarand Pemba”, and abolished the ZanzibarSultanate and banned the deposed Sultan Abdullah from returning. Free politics ceased as the state-run ASPbecame the sole legal party that was allowed to operate.

January 11, 2022

January 11, 1923 – Interwar Period: France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr region to force Germany to make reparation payments

When Germanydefaulted on war reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forcesoccupied the Ruhr region, Germany’sindustrial heartland, to force payment. At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passiveresistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coalminers and railway employees did not work. Both Germany and Francesuffered financial losses as a result. Following United Statesintervention, in August 1924, the two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , whereGerman reparations payments were restructured, and the U.S. and British government extended loans tohelp with Germany’seconomic recovery. French troops thenwithdrew From the Ruhr region. Subsequently in August 1929, with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’sreparations obligations were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58years. As a result of these and othermeasures, including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency,and easing bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s economy recovered andexpanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments entered the domestic market,and civil unrest declined.

(Taken from Weimar Republic – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Near the end of World War I, Germany was beset by severe internal tumult, asindustrial workers, including those involved in war production, launched strikeactions that were fomented by communist political and labor groups that longopposed Germany’sinvolvement in the war. Then in lateOctober-early November 1918 when German defeat in the war became imminent,German Navy sailors at the ports of Wilhelmshavenand Kielmutinied, and refused to obey their commanders who had ordered them to preparefor one final decisive battle with the British Navy. Within a few days, the unrest had spread tomany cities across Germany,sparking a full-blown communist-led revolt (the German Revolution) that peakedin January 1919, when democracy-leaning forces quelled the uprising. But in the chaos following German defeat inWorld War I, the monarchy under Kaiser (King) Wilhelm II ended, and wasreplaced by a social democratic state, the WeimarRepublic (named after the city of Weimar, where the newstate’s constitution was drafted).

The Weimar Republic, which governed Germany from 1919-1933, waspermanently beset by fierce political opposition and also experienced twofailed coup d’états. A full spectrum ofopposition political parties, from the moderate to radical right-wing,ultra-nationalist, and monarchist parties, to the moderate to extremeleft-wing, socialist, and communist parties, wanted to put and end to theWeimar Republic, either through elections or by paramilitary violence , and tobe replaced by a political system suited to their respective ideologies. One radical political movement that emergedat this time was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which came to beknown in the West as the Nazi Party, and its members called Nazis, and led byAdolf Hitler. The Nazis participated inthe electoral process, but wanted to end the Weimar democratic system. Hitler denounced the Versailles treaty, advocated totalitarianism,held racial views that extolled Germans as the “master race” and disparagedother races, such as Slavs and Jews, as “sub-humans”. The Nazis also were vehemently anti-communistand advocated lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism in Eastern Europe and Russia.

A common theme among right-wing, ultra-nationalist, andex-military circles was the idea that in World War I, Germanywas not defeated on the battlefield. Rather, German defeat was caused by traitors, notably the workers whowent on strike at a critical stage of the war and thus deprived soldiers at thefront lines of their much-needed supplies. As well, communists and socialists were to blame, since they fomentedcivilian unrest that led to the revolution; Jews, since they dominated thecommunist leadership; and the Weimar Republic since it signed the Versailles treaty. This concept, called the “stab in the back”theory, postulated that in 1918, Germany was on the brink of victory, but lost after being stabbed in the back by the “November criminals”, i.e.the communists, Jews, etc. After comingto power, the Nazis would appropriate the “stab in the back” theory to fittheir political agenda in order to denounce the Versailles treaty, suppress opposition, andestablish a dictatorship.

Germany,financially ravaged by the war, was hard pressed to meet its reparationsobligations. The government printedenormous amounts of money to cover the deficit and also pay off its war debts,but this led to hyperinflation and astronomical prices of basic goods, sparkingfood riots and worsening the economy. Then when Germanydefaulted on reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces occupiedthe Ruhr region, Germany’sindustrial heartland, to force payment. At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passiveresistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coalminers and railway employees did not work. Both Germany and Francesuffered financial losses as a result. Following United Statesintervention, in August 1924, the two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , whereGerman reparations payments were restructured, and the U.S. and British government extended loans tohelp with Germany’seconomic recovery. French troops thenwithdrew From the Ruhr region. Subsequently in August 1929, with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’sreparations obligations were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58years. As a result of these and othermeasures, including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency,and easing bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s economy recovered andexpanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments entered the domestic market,and civil unrest declined.

The Versailles treaty was aheavy blow to the German national morale, and was seen as a humiliation to the Weimar state, which hadbeen forced by the Allies to agree to it under threat of continuing thewar. From the start, the Weimar government was determined to implement re-armamentin violation of the Versaillestreaty. Throughout its existence from1919-1933, the Weimar Republic carried out small, clandestine, and subtlemeans to build its military forces, and was only restrained by the presence ofAllied inspectors that regularly visited Germanyto ensure compliance with the Versaillestreaty. These methods included secretlyreconstituting the German general staff, equipping and training the police forcombat duties, and tolerating the presence of paramilitaries with an eye tolater integrate them as reserve units in the regular army.

Also important to Germany’ssecret rearmament was the Weimar government’sopening ties with the Soviet Union. Relations began in April 1922 with the signingof the Treaty of Rapallo, which established diplomatic ties, and furthered inApril 1926 with the Treaty of Berlin, where both sides agreed to remain neutralif the other was attacked by another country. In the aftermath of World War I, the Germans and Soviets saw the need tohelp each other, as they were outcasts in the international community: theAllies blamed Germany forstarting the war, and also turned their backs on the Soviet Union for its communist ideology.

Military cooperation was an important component toGerman-Soviet relations. At theinvitation of the Soviet government, Weimar Germany built several military facilities in theSoviet Union; e.g. an aircraft factory near Moscow,an artillery facility near Rostov, a flyingschool near Lipetsk, a chemical weapons plant inSamara, a naval base in Murmansk,etc. In this way, Germany achieved some rearmament away fromAllied detection, while the Soviet Union, yetin the process of industrialization from an agricultural economy, gained accessto German technology and military theory.

January 10, 2022

January 10, 1961 – Bay of Pigs Invasion: The New York Times publishes the government’s secret planned invasion of Cuba

The CIA wanted to maintain utmostsecrecy in order to conceal the U.S.government’s involvement in the invasion. Through loose talk, however, the plan came to be widely known among theMiami Cubans, which eventually was picked up by the American media and then bythe foreign press. On January 10, 1961,a front-page news item in the New YorkTimes read “U.S.helps train anti-Castro Force At Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base”. Castro’s intelligence operatives in Latin America also learned of the plan; in October 1960,the Cuban foreign minister presented evidence of the existence of Brigade 2506at a session of the United Nations General Assembly.

Cuba showing location of Trinidad, which was the first proposed site of the CIA-sponsored Brigade 2506 invasion, and the Bay of Pigs, where the landings took place

(Taken from Bay of Pigs Invasion – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Background The rise to power of FidelCastro after his victory in the Cuban Revolution (previous article) caused great concern for the United States. Castro formed a government that adopted asocialist state policy and opened diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other European communist countries. After the Cuban government seized andnationalized American companies in Cuba, the United States imposed a tradeembargo on the Castro regime and subsequently ended all economic and diplomaticrelations with the island country.

Then in July 1959, just seven monthsafter the Cuban Revolution, U.S.president Dwight Eisenhower delegated the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with the task of overthrowing Castro, who had by then gainedabsolute power as dictator. The CIAdevised a number of methods to try and kill the Cuban leader, including the useof guns-for-hire and assassins carrying poison-laced devices. Other schemes to destabilize Cuba also werecarried out, including sending infiltrators to conduct terror and sabotageoperations in the island, arming and funding anti-Castro insurgent groups thatoperated especially in the Escambray Mountains, and by being directly involvedin attacking and sinking Cuban and foreign merchant vessels in Cuban waters andby launching air attacks in Cuba. TheseCIA operations ultimately failed to eliminate Castro or permanently destabilizehis regime.

In March 1960, the CIA began to plansecretly for the invasion of Cuba,with the full support of the Eisenhower administration and the U.S. ArmedForces. About 1,400 anti-Castro Cubanexiles in Miamiwere recruited to form the main invasion force, which came to be known as“Brigade 2506” (Brigade 2506 actually consisted of five infantry brigades and oneparatrooper brigade). The majority ofBrigade 2506 received training in conventional warfare in a U.S. base in Guatemala,while other members took specialized combat instructions in Puerto Rico andvarious locations in the United States.

The CIA wanted to maintain utmostsecrecy in order to conceal the U.S.government’s involvement in the invasion. Through loose talk, however, the plan came to be widely known among theMiami Cubans, which eventually was picked up by the American media and then bythe foreign press. On January 10, 1961,a front-page news item in the New YorkTimes read “U.S.helps train anti-Castro Force At Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base”. Castro’s intelligence operatives in Latin America also learned of the plan; in October 1960,the Cuban foreign minister presented evidence of the existence of Brigade 2506at a session of the United Nations General Assembly.

In January 1961, the CIA gave newlyelected U.S.president, John F. Kennedy, together with his Cabinet, details of the Cuban invasion plan. The State Department raised a number ofobjections, particularly with regards to the proposed landing site of Trinidad,which was a heavily populated town in south-central Cuba (Map 30). Trinidad had the benefits of being adefensible landing site and was located adjacent to the Escambray Mountains,where many anti-Castro guerilla groups operated. State officials were concerned, however, thatTrinidad’s conspicuous location and largepopulation would make American involvement difficult to conceal.

As a result, the CIA rejectedTrinidad, and proposed a new landing site: the Bayof Pigs (Spanish: Bahiade Cochinos), a remote, sparsely inhabited narrow inlet west of Trinidad. President Kennedy then gave his approval, andfinal preparations for the invasion were made. (The “Cochinos” in Bahia de Cochinos, although translatedinto English as “pigs” does not refer to swine but to a species of fish, theorange-lined triggerfish, found in the coral waters around the area).

The general premise of the invasion was that most Cubans werediscontented with Castro and wanted to see his government deposed. The CIA believed that once Brigade 2506 beganthe invasion, Cubans would rise up against Castro, and the Cuban Army woulddefect to the side of the invaders. Other anti-government guerilla groups then would join Brigade 2506 andincite a civil war that ultimately would overthrow Castro. Thereafter, a provisional government, led byCuban exiles in the United States, would arrive in Cuba and lead the transitionto democracy.

January 9, 2022

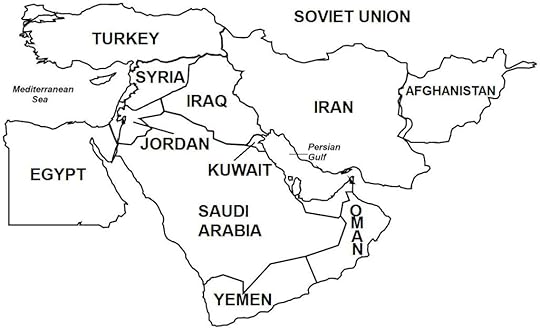

January 9, 1991 – Gulf War: U.S. and Iraqi officials meet to resolve the Kuwait issue

Iraq offered the UnitedStates a number of proposals to resolve the crisis, including that Iraqi forceswould be withdrawn from Kuwait on the condition that Israel also withdrew itstroops from occupied regions in Palestine (West Bank, Gaza Strip), Syria (GolanHeights, and southern Lebanon. The United States refused to negotiate, however,stating that Iraqmust withdraw its troops as per the UNSC resolutions before any talk ofresolving other Middle Eastern issues would be discussed. On January 9, 1991, as the UN-imposeddeadline of January 15, 1991 approached, U.S. Secretary of State James Bakerand Iraq’s Foreign MinisterTariq Aziz held last-minute talks in Geneva Switzerland(called the Geneva Peace Conference). But the two sides refused to tone down their hard-line positions,leading to the breakdown of talks and the imminent outbreak of war.

(Taken from Gulf War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

Background OnAugust 2, 1990, Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait, overthrew the rulingmonarchy and seizing control of the oil-rich country. A “Provisional Government of Free Kuwait”was established, and two days later, August 4, the Iraqi government, led bySaddam Hussein, declared Kuwaita republic. On August 8, Saddam changedhis mind and annexed Kuwaitas a “governorate”, declaring it Iraq’s 19th province.

Jaber III, Kuwait’s deposed emir who had fled toneighboring Saudi Arabiain the midst of the invasion, appealed to the international community. On August 3, 1990, the United NationsSecurity Council (UNSC) issued Resolution 660, the first of many resolutionsagainst Iraq, whichcondemned the invasion and demanded that Saddam withdraw his forces from Kuwait. Three days later, August 6, the UNSC releasedResolution 661 that imposed economic sanctions against Iraq, which was carried out througha naval blockade authorized under UNSC Resolution 665. Continued Iraqi defiance subsequently wouldcompel the UNSC to issue Resolution 678 on November 29, 1990 that set thedeadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait on or before January 15, 1991 as wellas authorized UN member states to enforce the withdrawal if necessary, eventhrough the use of force. The ArabLeague, the main regional organization, also condemned the invasion, although Jordan, Sudan,Yemen, and the Palestine LiberationOrganization (PLO) continued to support Iraq.

Iraq’s annexation of Kuwaitupset the political, military, and economic dynamics in the Persian Gulfregion, and by possessing the world’s fourth largest armed forces, Iraq now posed a direct threat to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. The United Statesannounced that intelligence information detected a build-up of Iraqi forces in Kuwait’s southern border with Saudi Arabia. Saddam, however, declared that Iraq had no intention of invading Saudi Arabia,a position he would maintain in response to allegations of his territorialambitions.

Meeting with U.S. Secretaryof Defense Dick Cheney who arrived in Saudi Arabia shortly after Iraq’sinvasion of Kuwait, SaudiKing Fahd requested U.S.military protection. U.S. PresidentGeorge H.W. Bush accepted theinvitation, as doing so would not only defend an important regional ally, butprevent Saddam from gaining control of the oil fields of Saudi Arabia, the world’s largestpetroleum producer. With its conquest ofKuwait, Iraq now held 20% of the world’s oil supply, butannexing Saudi Arabiawould allow Saddam to control 50% of the global oil reserves. By September 18, 1990, the U.S. government announced that the Iraqi Armywas massed in southern Kuwait,containing a force of 360,000 troops and 2,800 tanks.

U.S. military deployment to Saudi Arabia, codenamed Operation Desert Shield, was swift; on August 8, just six days after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait,American air and naval forces, led by two aircraft carriers and twobattleships, had arrived in the Persian Gulf. Over the next few months, Iraq offered theUnited States a number of proposals to resolve the crisis, including that Iraqiforces would be withdrawn from Kuwait on the condition that Israel alsowithdrew its troops from occupied regions in Palestine (West Bank, Gaza Strip),Syria (Golan Heights, and southern Lebanon. The United Statesrefused to negotiate, however, stating that Iraq must withdraw its troops asper the UNSC resolutions before any talk of resolving other Middle Easternissues would be discussed. On January 9,1991, as the UN-imposed deadline of January 15, 1991 approached, U.S. Secretaryof State James Baker and Iraq’sForeign Minister Tariq Aziz held last-minute talks in GenevaSwitzerland(called the Geneva Peace Conference). But the two sides refused to tone down their hard-line positions,leading to the breakdown of talks and the imminent outbreak of war.

Because Meccaand Medina, Islam’s holiest sites, were locatedin Saudi Arabia, King Fahdreceived strong local and international criticism from other Muslim states forallowing U.S.troops into his country. At the urgingof King Fahd, the United States organized a multinational coalition consistingof armed and civilian contingents from 34 countries which, apart from SaudiArabia and Kuwait’s (exiled forces), also included other Arab and Muslimcountries (Egypt, Syria, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Turkey,Morocco, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). A force of about 960,000 troops wasassembled, with U.S.soldiers accounting for 700,000 or about 70% of the total; Britain and France also sent sizablecontingents, some 53,000 and 18,000 respectively, as well as large amounts ofmilitary equipment and supplies.

In talks with Saudiofficials, the United Statesstated that the Saudi government must pay for the greater portion of the costfor the coalition force, as the latter was tasked specifically to protect Saudi Arabia. In the coming war, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, andother Gulf states contributed about $36 billion of the $61 billion coalition totalwar cost; as well, Germany and Japan contributed a combined $16 billion,although these two countries, prohibited by their constitutions from sendingarmies abroad, were not a combat part of the coalition force.

President Bush overcame thelast major obstacle to implementing UNSC Resolution 678 – the U.S.Congress. The U.S. Senate and House of Representativeswere held by a majority from the opposition Democratic Party, which was opposedto the Bush administration’s war option and instead believed that the UNSC’seconomic sanctions against Iraq, yet barely two months in force, must be giventime to work. On January 12, 1991, acongressional joint resolution that authorized war, as per President Bush’srequest, was passed by the House of Representatives by a vote of 250-183 andSenate by a vote of 52-47.

One major factor for U.S.Congress’ approval for war were news reports of widespread atrocities and humanrights violations being committed by Iraq’s occupation forces againstKuwaiti civilians, particularly against members of the clandestine Kuwaitiresistance movement that had arisen as a result of the occupation. Some of the more outrage-provoking accounts,including allegations that Iraqi soldiers pulled hundreds of new-born infantsfrom incubators and then left to die on the hospital floors, have since beendetermined to be untrue.

Iraq’s programs fordeveloping nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons were also cause for graveconcern to Western countries, particularly since during the Iran-Iraq War (thatended just three years earlier, in August 1988), Saddam did not hesitate to usechemical weapons, dropping bombs and firing artillery containing projectileslaced with nerve agents, cyanide, and sarin against Iranian military andcivilian targets, and even against his own people, i.e. Iraq Kurds who hadrisen up in rebellion and sided with Iran in the war.

January 8, 2022

January 8, 1987 – Iran-Iraq War: Iranian and Iraqi forces clash at the Battle of Basra

On January 8, 1987, Iranlaunched its long anticipated offensive on Basra, which became the largest and bloodiestbattle of the war. Some 600,000 Iraniansoldiers took part and faced 400,000 Iraqi defenders. The seven-week offensive, which lasted untillate February 1987, saw the Iranians launching successive assaults thatsucceeded in breaching four of the five Iraqi “dynamic defense” lines,including the modified barriers Fish Lake and Jasim River, and to come towithin twelve kilometers of Basra, before being stopped. Iranian casualties were considerable– some65,000 were killed; 20,000 Iraqi soldiers also perished.

The failure to capture Basrahad a powerful demoralizing effect on Iran: in the aftermath, much fewercivilians volunteered to join the Revolutionary Guards and Basij, the generalpopulation became war-weary and felt the war was unwinnable, and even theIranian leadership stopped plans for further major operations or “finaloffensives”.

(Excerpts taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In1937, the now independent monarchies of Iraq and Iran signed an agreement thatstipulated that their common border on the Shatt al-Arab was located at the lowwater mark on the eastern (i.e. Iranian) side all across the river’s length,except in the cities of Khoramshahr and Abadan, where the border was located atthe river’s mid-point. In 1958, theIraqi monarchy was overthrown in a military coup. Iraqthen formed a republic and the new government made territorial claims to thewestern section of the Iranian border province of Khuzestan,which had a large population of ethnic Arabs.

In Iraq,Arabs comprise some 70% of the population, while in Iran,Persians make up perhaps 65% of the population (an estimate since Iran’spopulation censuses do not indicate ethnicity). Iran’s demographicsalso include many non-Persian ethnicities: Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchs, andothers, while Iraq’ssignificant minority group comprises the Kurds, who make up 20% of thepopulation. In both countries, ethnicminorities have pushed for greater political autonomy, generating unrest and apotential weakness in each government of one country that has been exploited bythe other country.

The source of sectarian tension in Iran-Iraq relationsstemmed from the Sunni-Shiite dichotomy. Both countries had Islam as their primary religion, with Muslimsconstituting upwards of 95% of their total populations. In Iran, Shiites made up 90% of all Muslims(Sunnis at 9%) and held political power, while in Iraq, Shiites also held amajority (66% of all Muslims), but the minority Sunnis (33%) led by Saddam andhis Baath Party held absolute power.

In the 1960s, Iran, which was still ruled by amonarchy, embarked on a large military buildup, expanding the size and strengthof its armed forces. Then in 1969, Iran ended its recognition of the 1937 borderagreement with Iraq,declaring that the two countries’ border at the Shatt al-Arab was at theriver’s mid-point. The presence of thenow powerful Iranian Navy on the Shatt al-Arab deterred Iraq from taking action, andtensions rose.

Also by the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurdswere holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the FirstIraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting brokeout in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily byIran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt,particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqiforces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countriessigned the Algiers Accord in March 1975, where Iraqyielded to Iran’s demandthat the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iranended its support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq wasdispleased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional militarypower, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues)during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and evenenjoyed a period of rapprochement. As aresult of Iran’s assistancein helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelledAyatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iraniancleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worsetowards the end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’sabsolute ruler. Each of the two rivalcountries resumed secessionist support for the various ethnic groups in theother country. Iran’s transition to a full IslamicState was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revoltsby Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. TheIranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan,where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian governmentforces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreadingIslamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiite majority to overthrowSaddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish an Islamic State. In April 1980, a spate of violence attributedto the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran-supported militant group, broke out in Iraq,where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking governmentofficials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashedrepressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands whowere thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand Ayatollah MohammadBaqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslim countriesas the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamic community.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke outbetween forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency bySeptember of that year. As to theofficial start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when theIranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns,prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accordand declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as thestart of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and groundoffensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capableof achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors,all resulting from the Iranian Revolution. First, as previously mentioned, Iranfaced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’sadoption of Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iranfurther was wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of therevolution (liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposedthe Islamist hardliners’ rise to power. The Islamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressedall forms of dissent. Third, therevolution seriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as militaryelements, particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah,was purged and repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamicgovernment, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology,became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

January 7, 2022

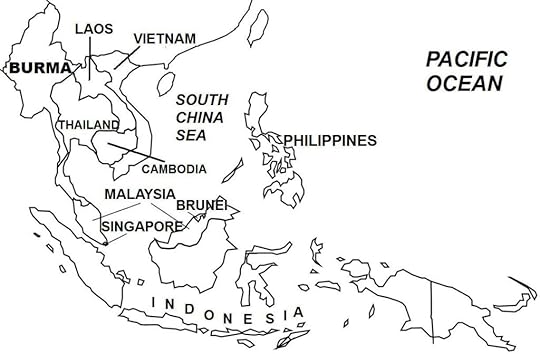

On January 7, 1979 – Cambodian-Vietnamese War: Vietnamese forces capture Phnom Penh

On January 7, 1979, the Vietnamese Army captured theCambodian capital of Phnom Penhin a blitzkrieg campaign and overthrew the Khmer Rouge regime. Pol Pot and his staff, together the bulk ofthe Khmer Rouge Army, made a strategic withdrawal to the jungle mountains ofwestern Cambodianear the Thai border, where they set up a resistance government.

(Taken from Cambodian-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 5)

Background Therevolutionary movements that eventually prevailed in Vietnamand Cambodia (as well as in Laos)trace their origin to 1930 when the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) wasformed. VCP soon reorganized itself intothe Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) to include membership to Cambodian andLaotian communists into the Vietnamese-dominated movement. The great majority of ICP Khmers were notindigenous to Cambodia;rather they consisted mostly of ethnic Khmers who were native to southern Vietnam, and ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia.

In 1951, the ICP split itself into three nationalistorganizations for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos respectively, i.e. Workers Partyof Vietnam, Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP), and Neo Lao Issara. In December 1946, the Viet Minh (or Leaguefor the Independence of Vietnam), a Vietnamese nationalist group that wasformed in World War II to fight the Japanese, began an independence war againstFrench rule (First Indochina War, separate article). The Viet Minh prevailed in July 1954. The 1954 Geneva Accords, which ended the war,divided Vietnam into twomilitary zones, which became socialist North Vietnam and West-aligned South Vietnam. War soon broke out between the two Vietnams, with North Vietnam supported by Chinaand the Soviet Union; and South Vietnamsupported by the United States. This Cold War conflict, called the Vietnam War (separate article) andwhich included direct American military involvement in 1965-1970, ended inApril 1975 with a North Vietnamese victory. As a result, the two Vietnamswere reunified, in July 1976.

Meanwhile in Cambodia,the local revolutionary struggle ended with the 1954 Geneva Accords, which gavethe country, led by King Sihanouk, full independence from France. The Accords also ended both French rule andFrench Indochina, and independence also was granted to Laos and Vietnam. Following the First Indochina War, most ofthe Khmer communists moved into exile in North Vietnam, while those who remained in Cambodia formed the PracheachonParty, which participated in the 1955 and 1958 elections. However, government repression forcedPracheachon Party members to go into hiding in the early 1960s.

By the late 1950s, the Cambodian communist movementexperienced a resurgence that was spurred by a new generation of young,Paris-education communists who had returned to the country. In September 1960, ICP veteran communists andthe new batch of communists met and elected a Central Committee, and renamedthe KPRP (Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party) as the Worker’s Party ofKampuchea (WPK).

In February 1963, following another government suppressionthat led to the arrest of communist leaders, the WPK soon came under thecontrol of the younger communists, led by Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot),who sidelined the veteran communists whom they viewed as pro-Vietnamese. In September 1966, the WPK was renamed theKampuchean Communist Party (KCP).

The KCP and its members, as well its military wing, werecalled “Khmer Rouge” by the Sihanouk government. In January 1968, the Khmer Rouge launched arevolutionary war against the Sihanouk regime, and after Sihanouk wasoverthrown in March 1970, against the new Cambodian government. In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge triumphed andtook over political power in Cambodia,which it renamed Democratic Kampuchea.

During its revolutionary struggle, the Khmer Rouge obtainedsupport from North Vietnam,particularly through the North Vietnamese Army’s capturing large sections ofeastern Cambodia,which it later turned over to its Khmer Rouge allies. But the Khmer Rouge held stronganti-Vietnamese sentiment, and deemed its alliance with North Vietnam only as a temporary expedient tocombat a common enemy – the United States in particular, Western capitalism ingeneral. The Cambodian communists’hostility toward the Vietnamese resulted from the historical domination byVietnam of Cambodia during the pre-colonial period, and the perception thatmodern-day Vietnam wanted todominate the whole Indochina region.

Soon after coming to power, the Khmer Rouge launched one ofhistory’s most astounding social revolutions, forcibly emptying cities, towns,and all urban areas, and sending the entire Cambodian population to thecountryside to become peasant workers in agrarian communes under a feudal-typeforced labor system. All lands andproperties were nationalized, banks, schools, hospitals, and most industries,were shut down. Money was abolished. Government officials and military officers ofthe previous regime, teachers, doctors, academics, businessmen, professionals,and all persons who had associated with the Western “imperialists”, or weredeemed “capitalist” or “counter-revolutionary” were jailed, tortured, andexecuted. Some 1½ – 2½ million people,or 25% of the population, died under the Khmer Rouge regime (CambodianGenocide, previous article).

In foreign relations, the Khmer Rouge government isolateditself from the international community, expelling all Western nationals,banning the entry of nearly all foreign media, and closing down all foreignembassies. It did, however, later allowa number of foreign diplomatic missions (from communist countries) to reopen inPhnom Penh. As well, it held a seat in the United Nations(UN).

The Khmer Rouge was fiercely nationalistic and xenophobic,and repressed ethnic minorities, including Chams, Chinese, Laotians, Thais, andespecially the Vietnamese. Within a fewmonths, it had expelled the remaining 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese from thecountry, adding to the 300,000 Vietnamese who had been deported by the previousCambodian regime.

January 6, 2022

January 6, 1951 – Korean War: South Korean government perpetrate the Ganghwa Massacre

On January 6, 1951, South Korean soldiers, police andmilitia executed between 200 – 1,300 civilians in Ganghwa, Incheon in South Korea.The perpetrators believed that the victims were collaborators of the NorthKorean Army. Many massacres and atrocities were committed by both sides duringthe Korean War.

(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

During World War II, theAllied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of Japanese territorialholdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea,at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United States, Britain,and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free andindependent”. Then at the YaltaConference of February 1945,the Soviet Union promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacificin two or three months after the European theater of World War II ended.

East Asia

East AsiaThen with the Soviet Armyinvading northern Korea onAugust 9, 1945, the United Statesbecame concerned that the Soviet Union might well occupy the whole Korean Peninsula. The U.S.government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S.military plan to divide Koreaat the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, whichthe latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continuedmoving south and stopped at the 38th parallel on August 16,1945. U.S.forces soon arrived in southern Koreaand advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8,1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S.and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in theirrespective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commandsestablished military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Sovietgovernments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-yeartrusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-SovietJoint Commission would work out the process of forming a Koreangovernment. But after a series ofmeetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Koreanquestion to the United Nations (UN). Thereasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutuallyacceptable Korean government are three-fold and to some extent allinterrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviettrusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based politicalfactions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politicallyand ethnically integrated state, although its independence often wasinterrupted by the invasions by its powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, inthe immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, andviewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run theirown affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’spolitical climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, fromright-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashedwith each other for political power. Asa result of Japan’sannexation of Koreain 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were theunrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea”led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and acommunist-allied anti-Japanese partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men wouldplay major roles in the Korean War. Atthe same time, tens of thousands of Koreans took part in the SecondSino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese Civil War, joiningand fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces,or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japaneseresistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria,was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated Western-style capitalist democracy, while othersespoused Soviet communism. However, allwere strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China,and Korea.

On their arrival in thesouthern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rulethrough the United States Army Military Government In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean CommunistParty in Seoul(the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeatedJapanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Koreanpeninsula. Then two days before U.S.forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee”proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under theauspices of a U.S. militaryagent, Syngman Rhee, the former president of the “Provisional Government ofthe Republic of Korea”arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize thecommunist Korean People’s Republic, as well as the pro-West “ProvisionalGovernment”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form apolitical coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S.sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South KoreanInterim Legislative Assembly. However,this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wingand right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S.authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence brokeout in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest wascarried out by left-aligned workers, farmers, and students, leading to manydeaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resultedfrom non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators orsettling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part ofa communist plot. They thereforedeclared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S.military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went intohiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would playa role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northernzone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under acoalition of nationalists, Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet RedArmy officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’sCommittee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by KimIl-sung who soonconsolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), andnationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic andreconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy industry.

By 1947, the Cold War hadbegun: the Soviet Union tightened its holdon the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a newforeign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed atstopping the spread of communism. The United States also implemented the MarshallPlan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which wascondemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed atdividing Europe. As a result, Europebecame divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting thesedevelopments, in Korea bymid-1945, the United Statesbecame resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of theKorean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanentdivision along ideological grounds. InSeptember 1947, with U.S. Congress rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S. government turned over theKorean issue to the UN. In November1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called forelections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was to be overseen by a newlyformed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Sovietgovernment rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had nojurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented UNTCOK representativesfrom entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were heldonly in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experiencedwidespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, alegislative body. Two months later (in July1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution whichestablished a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats,was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic of Korea(soon more commonly known as South Korea),ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.

A consequence of the SouthKorean elections was the displacement of the political moderates, because oftheir opposition to both the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communistSyngman Rhee was willing toallow the (temporary) partition of the peninsula. Subsequently, the United States moved to support theRhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates whom USAMGIK hadbacked initially.