Daniel Orr's Blog, page 47

October 16, 2021

October 16, 1934 – Chinese Civil War: Mao Zedong leads Chinese communists on the year-long historic Long March

Facing annihilation by the effective Nationalist offensivestrategy, Mao and his 80,000 Communist followers were forced to make a breakoutand escaped through a weakly defended section in the Nationalists’encirclement. Mao and his followers then began their historic Long March, an 8,000-mile, year-long foot journey towardYan-an in Shaanxi Province in northern China. Along the way, theyendured pursuing Nationalist forces, hostile indigenous tribes, starvation anddiseases, and natural barriers that included freezing, snow-covered mountains,raging rivers, and a vast expanse of swampland.

(Taken from Chinese Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 1)

Soon learning of the existence of Mao Zedong’s Chinese SovietRepublic, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek senthis forces to attack Jiangxiand other Communist-held regions. However, Mao’s Communists in Jiangxi were well-entrenchedin fortified positions, forcing the Nationalists to mount five militarycampaigns from 1929 to 1935. Three of these campaigns ended in failureswhile a fourth was abandoned when the Nationalist forces were redeployedfollowing Japan’s invasion ofManchuria innorthern China. In the fifth attempt, Chiang’s forces changed tactics from a costly frontalattack as in the previous campaigns to a slow, deliberate encirclement andconstriction of the enemy positions.

Facing annihilation by the effective Nationalist offensivestrategy, Mao and his 80,000 Communist followers were forced to make a breakoutand escaped through a weakly defended section in the Nationalists’encirclement. Mao and his followers then began their historic Long March, an 8,000-mile, year-long foot journey towardYan-an in Shaanxi Province in northern China. Along the way, theyendured pursuing Nationalist forces, hostile indigenous tribes, starvation anddiseases, and natural barriers that included freezing, snow-covered mountains,raging rivers, and a vast expanse of swampland.

Only 6,000 of Mao’s followers survived the journey – lessthan a tenth of the original number that had set out. Other Communistforces, including two large armies, also escaped the Nationalists’ encirclementand embarked on their own journeys through different routes, with all making itto Yan’an. Mao hadarrived there first, however, with the most survivors, and had established hisauthority over the Chinese Communists, which thereafter was not challenged.

On learning that the Communists had escaped to Yan’an,Chiang travelled to northern Chinain December 1936 to plan his attack against Mao’s forces. However, theNationalist commanders in Yan’an were infuriated that the Japanese had invaded Manchuria and were annexing Chinese territories whilefellow Chinese were fighting each other. At gunpoint, the Nationalistcommanders forced Chiang to cancel his campaign against the Red Army andagree to a Nationalist-Communist alliance to fight the Japanese.

China’s provinces that were affected during the Chinese Civil War

On learning of the alliance, the Japanese forces launcheda pre-emptive, full-scale invasion of China in July 1937. Theyeasily captured the coastal cities of China’seastern provinces; the Nationalist strongholds of Shanghai,Nanjing, and Wuhan also fell.

The events during the Japanese invasion turned the tide ofthe Chinese Civil War away from the Nationalists in favor of theCommunists. The major Japanese offensives were conducted along China’scoastal, central, and later, with the outbreak of World War II in thePacific, in the southern regions, all of which were Nationalist-heldterritories. These offensives inflicted great losses in men and materialto the Nationalist forces. In the defense of Shanghai, for example, Chiang lost 200,000 soldiersand his best military commanders.

Chiang also committed major military blunders. At Nanjing, for instance, he allowed his forces to betrapped and then destroyed. Consequently, the Japanese killed 200,000civilians and soldiers in the city. Then in a scorched earth strategy todelay the enemy’s advance, Chiang ordered the dams destroyed around Nanjing, which caused the Yellow River to flood and kill 500,000 people. Furthermore, as theNationalist forces retreated westward, they set fire to Changsha toprevent the city’s capture by the Japanese, but this resulted in the deaths of20,000 residents and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more, who werenot told of the plan.

The Chinese people’s confidence in their governmentplummeted, as it seemed to them that the Nationalist Army was incapable ofsaving the country. At the same time, the Communists’ popularity soaredbecause, unlike the Nationalists who used costly open warfare against theJapanese, the Red Army employed guerilla tactics with great success against themostly lightly defended enemy outposts in remote areas.

Soon, Chiang realized the futility of resisting the vastlysuperior Japanese forces. He therefore preferred to retreatinstead of committing large numbers of troops into battle. Furthermore,he wanted to conserve his forces for what he believed was the eventualcontinuation of the war with the Communists. The civilian population wasinfuriated, however, as they believed that the Japanese were the enemy to befought and under whom they were undergoing so much suffering.

In reality, the Nationalist-Communist alliance wassuperficial, for although the two sides fought the Japanese in their respectiveareas of control, considerable tensions existed between the two rival Chineseforces that sometimes led to the outbreak of skirmishes for control ofterritories that had not yet fallen to the Japanese. In January 1941, thefragile alliance was broken when the Nationalist forces attacked the Red Army in Anhui and Jiangsu,killing thousands of Communist soldiers.

October 15, 2021

October 15, 1904 – Russo-Japanese War: The Russian Baltic Fleet embarks on a seven-month, 33,000 km voyage to the Far East

In October 1904, while the JapaneseThird Army was yet besieging Port Arthur, TsarNicholas II ordered the Russian Baltic Fleet, which wasled by eight battleships, to head for Port Arthur and break the Japanese naval blockade, andreinforce the Russian Pacific Fleet. TheRussian Baltic Fleet, soon renamed the Second Pacific Fleet, then embarked on aseven-month (October 1904-May 1905) 33,000-kilometer voyage half-way around theworld by way of the Cape of Good Hope, and around the southern tip of Africa. TheRussian fleet was forced to take this much longer route after being deniedpassage across the Suez Canal by Britainfollowing the Dogger Bank incident. In this incident, which occurred in the North Sea in October 1904, the Russian fleet fired onBritish trawlers, mistaking them for Japanese torpedo boats. The incident sparked a furious Britishgovernment protest that nearly led to war between Britainand Russia.

(Taken from Russo-Japanese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

The Battle of Mukden (February 20-March 10, 1905), which was thelast major land battle of the war, opened with the Japanese main offensiveaimed at the Russian flanks, with minor attacks at other points. Again, Russian military plannersmiscalculated the Japanese plan, believing that the main enemy thrust would bealong the eastern flank, when in fact the Japanese focused their offensive inthe west. There, the Japanese SecondArmy comprised the main attacking force and the Japanese Third Army was taskedwith advancing in a wide arc in the northwest to the other side of Mukden.

Soon realizing the threat of beingencircled, General Kuropatkin moved units from the eastern flank to thewestern flank, which was badly executed. The Japanese now attacked in force along the weakened Russian easternflank, breaking through. In the west,the Japanese soon threatened to encircle the Russians. Faced with annihilation, on March 9, 1905, onGeneral Kuropatkin’s orders, Russianforces abandoned Mukden,and retreated north first to Tiehling. The Russians soon also evacuated Tiehling, which they burned to theground, and retreated further north to Hspingkai. In the Mukdenbattle, a combined total of 165,000 soldiers were casualties (Japanese: 75,000,including 16,000 killed; Russians: 90,000, including 9,000 killed).

In the aftermath, Japanese forcesoccupied Mukden and gained control of the entire southern Manchuria. Butthey had failed to annihilate the Russian Army (which remained relativelypotent despite the high losses). Becauseof serious logistical problems, the Japanese Army decided to abandon plans toadvance further north.

Despite the series of battlefielddefeats, Tsar Nicholas II continued to believe that the Russian Armywould prevail eventually in a protracted war. The now completed Trans-Siberian Railway could transfer more troops andweapons to the Far East. But these hopes would be dashed in the Battleof Tsushima.

Route of the Russian Baltic Fleet from Russia to East Asia. Solid line indicates the route taken; dashed line shows the alternative route through the Suez Canal

Route of the Russian Baltic Fleet from Russia to East Asia. Solid line indicates the route taken; dashed line shows the alternative route through the Suez Canal In October 1904, while the JapaneseThird Army was yet besieging Port Arthur, TsarNicholas II ordered the Russian Baltic Fleet, which wasled by eight battleships, to head for Port Arthur and break the Japanese naval blockade, andreinforce the Russian Pacific Fleet. TheRussian Baltic Fleet, soon renamed the Second Pacific Fleet, then embarked on aseven-month (October 1904-May 1905) 33,000-kilometer voyage half-way around theworld by way of the Cape of Good Hope, and around the southern tip of Africa. TheRussian fleet was forced to take this much longer route after being deniedpassage across the Suez Canal by Britainfollowing the Dogger Bank incident. In this incident, which occurred in the North Sea in October 1904, the Russian fleet fired onBritish trawlers, mistaking them for Japanese torpedo boats. The incident sparked a furious Britishgovernment protest that nearly led to war between Britainand Russia.

In January 1905, while yet in transit,the Russian fleet received information that Port Arthur had fallen. As a result, it was instructed tohead for Vladivostok instead. By May 1905, the Russian fleet had entered the waters south of the Seaof Japan, and while traversing the TsushimaStrait, located between Japan and Korea, the fleet was spotted by aJapanese ship, which then alerted the Japanese Navy. In the previous months, the Japanese hadfollowed the progress of the Russian fleet’s voyage, and thus prepared to dobattle with it in a decisive showdown.

In the ensuing Battle of Tsushima (May 27-28, 1905), the Japanese Navy scored astunning one-sided victory. The RussianSecond Pacific Fleet was destroyed, with 10,000 Russians killed or captured, 21ships sunk, including 7 battleships, and of the 38 Russian ships that startedthe voyage, only 3 managed to reach Vladivostok. Japanese losses were 700 dead or wounded, andonly 3 torpedo boats sunk.

The Battle of Tsushima sentreverberations around the World – an Asian nation dealing a crushing defeat ona European power. In Russia, Tsar Nicholas II abandoned his hard-line position against Japan. On June 8, 1905, one week after the Tsushimabattle, Russiaagreed to negotiate an end to the war. By this time also, Russiawas experiencing massive unrest (the Russian Revolution of 1905) as a result ofstrikes, demonstrations, peasant protests, and soldiers’ mutinies. This unrest in Russia began in January 1905 when apeaceful demonstration by 150,000 people turned violent when soldiers openedfire and killed scores of people. Russians across the country then rose up against the government. Some military units mutinied, but werecontained by loyalist forces. Railworkers and rebellious soldiers seized sections of the Trans-Baikal railway,undermining the Russian war effort in the east. In the end, the Russian government quelled the uprising after agreeingto implement major reforms.

Meanwhile, Japan was faced with adeteriorating economy and mounting foreign debt, and also desired to end thewar. The Japanese Army was experiencinglogistical problems in Manchuria, and the economic problems at home couldseriously undermine Japan’sability to wage a protracted war. Asearly as mid-1904, Japanhad sought third-party mediation to end the war. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt agreed toact as mediator, and peace talks opened in Portsmouth, New Hampshirein June 1905. Russian and Japanesemediators took a hard-line stance and refused to compromise. As a result, fighting resumed. In July 1905, Japanese naval and land forcesseized Sakhalin Island, located off the Russian Far Eastmainland, in a three-week campaign.

Negotiations then continued. In August 1905, a number of issues wereresolved, but the two sides remained deadlocked over the more contentiousissues of war reparations and territorial concessions. The Russian delegation threatened to withdrawfrom the talks and allow the war to continue. The Japanese then acquiesced, and agreed to the Russian stipulation thatno war reparations would be paid.

October 14, 2021

October 14, 1962 – Cuban Missile Crisis: A U.S. reconnaissance plane takes photographs of a Soviet nuclear installation being built in Cuba

On October 14, 1962, a U-2 spy planetook hundreds of photographs which, after being filtered and analyzed by theCIA, revealed the construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio Province (Map34) of a Soviet nuclear missile site for MRBMs that were capable of strikingwithin a range of 2,000 kilometers, including Washington, D.C. and the wholesoutheastern United States.

(Taken from Cuban Missile Crisis – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 2)

Background After the unsuccessful Bay ofPigs Invasion in April 1961 (previousarticle), the United Statesgovernment under President John F. Kennedy focused on clandestine methods tooust or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and/or overthrow Cuba’s communist government. In November 1961, a U.S. covert operationcode-named Mongoose was prepared, which aimed at destabilizing Cuba’s politicaland economic infrastructures through various means, including espionage,sabotage, embargos, and psychological warfare. Starting in March 1962, anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Florida,supported by American operatives, penetrated Cuba undetected and carried outattacks against farmlands and agricultural facilities, oil depots andrefineries, and public infrastructures, as well as Cuban ships and foreignvessels operating inside Cuban maritime waters. These actions, together with the United States Armed Forces’ carryingout military exercises in U.S.-friendly Caribbean countries, made Castrobelieve that the United Stateswas preparing another invasion of Cuba.

From the time he seized power in Cuba in 1959, Castro had increased the size andstrength of his armed forces with weapons provided by the Soviet Union. In Moscow,Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev also believed that anAmerican invasion was imminent, and increased Russian advisers, troops, andweapons to Cuba. Castro’s revolution had provided communismwith a toehold in the Western Hemisphere andPremier Khrushchev was determined not to lose this invaluable asset. At the same time, the Soviet leader began toface a security crisis of his own when the United States under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) installed 300 Jupiternuclear missiles in Italyin 1961 and 150 missiles in Turkey(Map 33) in April 1962.

In the nuclear arms race between thetwo superpowers, the United Statesheld a decisive edge over the Soviet Union,both in terms of the number of nuclear missiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in thereliability of the systems required to deliver these weapons. The American advantage was even morepronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs (Intercontinental BallisticMissiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps no more than a dozen missileswith a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which when launched from the U.S. mainland could accurately hit specifictargets in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear weapons technologyhad been focused on the more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted ofshorter range missiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba, which was located only 100miles from southeastern United States, could target portions of the contiguous48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such adeployment would serve Castro as a powerful deterrent against an Americaninvasion; for the Soviets, they would have invoked their prerogative to installnuclear weapons in a friendly country, just as the Americans had done in Europe. Moreimportant, the presence of Soviet nuclear weapons in the Western Hemispherewould radically alter the global nuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a directthreat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchevconceived of such a plan, and felt that the United States would respond to itwith no more than a diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take militaryaction. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchevbelieved that President Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because ofthe American president’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of PigsInvasion in April 1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the EastGerman-Soviet building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba A Sovietdelegation sent to Cubamet with Fidel Castro, who gave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cuba and the Soviet Unionsigned an agreement pertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of theproject was done in utmost secrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cubanofficials being informed. In Cuba,Soviet technical and military teams secretly identified the locations for thenuclear missile sites.

In August 1962, U.S. reconnaissance flights over Cubadetected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraftand 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent tothe deployment of nuclear missiles. Bylate August, the U.S.government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets wereintroducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missileshad reached Cubaby Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventionalweapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiersposing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’sdefense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cubapossessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks,and 150 planes.

October 13, 2021

October 13, 1921 – The Treaty of Kars is signed, delineating the border between Turkey and the Soviet Union

In the aftermath of the Eastern Front of the TurkishWar of Independence, the Ankara government and the Soviet Union made peace andfixed the Turkish-Soviet border under two treaties: the Treaty of Moscow (March 16, 1921) and the Treaty of Kars (October 13, 1921); the treaties also endedthe war in the eastern sector.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

War Turkish nationalistsfought in three fronts: in the east against Armenia,in the south against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece,which was backed by Britain.

Eastern FrontAlso known as the Turkish-Armenian War, the eastern front carried over from hostilities in theCaucasus Sector of World War I. Russianforces had gained control of the Caucasus and northeast Turkey, but withdrew from theregion in 1917 following the outbreak of the Russian Revolution. Later that year, the Ottomans and the Sovietgovernment signed an armistice.

After the Russians withdrew,the South Caucasus jurisdictions of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan formed the short-lived TranscaucasianDemocratic Federative Republic in February 1918. Then after the federation’s dissolution inMay 1918, the three members declared separate independences. Armenia,which in the context of World War I supported the Allied Powers, went to waragainst the Ottoman Empire. The nascent Armenian state was dealt a numberof defeats from a powerful Ottoman offensive, but survived the war.

At the end of World War I,United States PresidentWoodrow Wilson, in line with his “Fourteen Points” Manifesto regarding the peoples’ right ofself-determination, proposed a new, much enlarged Armenian state, subject tocertain conditions. This so-called“Wilsonian Armenia” subsequently wasincluded in the Treaty of Sevres. Whileethnic Armenians welcomed the proposal as genuinely reflecting historical andgeographical Armenian territory, the Turkish “government” in Ankara opposed it on the same grounds thatthe proposed change would encroach on the Turkish people’s traditional andancestral homeland.

War Following border skirmishes in June 1920, Armeniantroops seized Oltu, a coal-rich town in Georgia. Turkish forces associated with Kemal’sgovernment had a strong presence in eastern Turkey. By contrast, Armenia’s prospects for victorywas dependent on Allied support which, however, proved to be limited in supplyand weak-hearted, which ultimately decided the outcome in this sector of thewar.

Turkish forces began their offensive on September13, easily overrunning the towns of Oltu and Peniak. On September 28, the border town of Sarikamis was taken as well, forcing Armenian forces toretreat to Kars, a fortified city in western Armenia. On October 24, 1920, Turkish forcesentered Armenia and attackedKars, which wastaken after one week of fighting.

The Turks then rapidly advanced to Alexandropol, 280kilometers away, which also was captured, on November 6. Yerevan,the Armenian capital, now came under direct threat. On November 18, 1920, the Armenian governmentacquiesced to a Turkish ultimatum, and a ceasefire came into effect. On December 2, 1920, the Armenian and Ankara governments signed the Treaty of Alexandropol, whereby Armeniaceased its claim to “Wilsonian Armenia” as stipulated in the Treaty ofSevres. The Alexandropol treaty alsoforced Armenia to cede Kars and surrounding regions; in total, some 50% ofArmenian territory was lost, i.e. Armenia retained only one-half ofits pre-war borders.

The Armenian state was dealt a death blow when theSoviet Union, on the pretext of a border dispute, invaded from Azerbaijan. On December 4, 1920, Yerevan fell to the Russians, and those partsnot yet under Turkish occupation came under Soviet control. Armenian communists then formed a newgovernment, bringing the country under indirect Soviet politicalauthority. The Soviet invasion of Armenia was part of the Moscowgovernment’s strategy to bring the Caucasus under the Soviet Union, a plan thatwas achieved when Georgiaalso was invaded by the Russians the following year.

The Eastern front in the Turkish War of Independence

The Eastern front in the Turkish War of IndependenceIn the aftermath, the Ankaragovernment and the Soviet Union made peace andfixed the Turkish-Soviet border under two treaties: the Treaty of Moscow (March 16, 1921) and the Treaty of Kars (October 13, 1921); the treaties also endedthe war in the eastern sector.

October 12, 2021

October 12, 1970 – Vietnam War: U.S. President Nixon announces that 40,000 more troops will be withdrawn from Vietnam before Christmas

In 1969,newly elected U.S.president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year,continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement andphased troop withdrawal from Vietnam,while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and materialsupport. He also was determined toachieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Parispeace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February1969, the Viet Cong againlaunched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, andAmerican bases. Two weeks later, theViet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S.planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases ineastern Cambodia(along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed OperationMenu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal(May 1970-August 1973), with the latter targeting a wider insurgent-heldterritory in eastern Cambodia.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Towards disengagement In 1968, because of domestic pressures, the Johnsonadministration implemented a major shift in American involvement in the war:henceforth, the U.S. military would gradually disengage from the Vietnam War,and after a period of being built up, the South Vietnamese military would takeover the fighting (the process known as the “Vietnamization” of the war). The South Vietnamese military buildup wasmeant to balance out the phased reduction of U.S. ground forces. U.S.forces in Vietnam,which peaked in 1968 at 530,000 troops, would see a steady reduction insucceeding years: 1969 – 475,000; 1970 – 335,000; 1971-156,000; 1972 – 24,000;and 1973 – 50. More than these numbersalone, the pull-out of American troops would have a decisive impact on the outcomeof the war.

In June 1968,General Creighton Abrams, who succeeded as over-all commander of U.S.forces in Vietnam (MACV), gradually shifted U.S. combat strategy away fromsearch and destroy missions to “clear and hold” (i.e. to clear the insurgentsfrom an area, which would then be held) operations, and implemented amoderately successful “hearts and minds” campaign (under a newly formed agency,the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support, CORDS) to gain the sympathy of the civilianpopulation for the South Vietnamese government.

In 1969,newly elected U.S.president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year,continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement andphased troop withdrawal from Vietnam,while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and materialsupport. He also was determined toachieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Parispeace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February1969, the Viet Cong againlaunched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, andAmerican bases. Two weeks later, theViet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S.planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases ineastern Cambodia(along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed OperationMenu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal(May 1970-August 1973), with the latter targeting a wider insurgent-heldterritory in eastern Cambodia.

In the 1954Geneva Accords, Cambodiahad declared its neutrality in regional conflicts, a policy it maintained inthe early years of the Vietnam War. However, by the early 1960s, Cambodia’sreigning monarch, Norodom Sihanouk, came under great pressure by the escalating warin Vietnam, and especiallyafter 1963, when North Vietnamese forces occupied sections of eastern Cambodia as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail systemto South Vietnam. Then inthe mid-1960s, Sihanouk signed security agreements with China and North Vietnam, where in exchange for receiving economicincentives, he acquiesced to the North Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia. He also allowed the use of the port of Sihanoukville(located in southern Cambodia)for shipments from communist countries for the Viet Cong/NLF through a newly opened land route across Cambodia. This new route, called the Sihanouk Trail(Figure 5) by the Western media, became a major alternative logistical systemby North Vietnamduring the period of intense American air operations over the Laotian side ofthe Ho Chi Minh Trail.

In July 1968,under strong local and regional pressures, Sihanouk re-openeddiplomatic relations with the United States, and his government swung to beingpro-West. However, in March 1970, he wasoverthrown in a coup, and a hard-line pro-U.S. government under President LonNol abolishedthe monarchy and restructured the country as the Khmer Republic. For Cambodia, the spill-over of the Vietnam War intoits territory would have disastrous consequences, as the fledging communistKhmer Rouge insurgentswould soon obtain large North Vietnamese support that would plunge Cambodiainto a full-scale civil war. For the United States (and South Vietnam), the pro-U.S. Lon Nol government served as a greenlight for American (and South Vietnamese) forces to conduct military operationsin Cambodia.

The U.S. bombing operations on Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia forced North Vietnam to increase its military presence in other partsof Cambodia. The North Vietnamese Army seized controlparticularly of northeastern Cambodia,where its forces defeated and expelled the Cambodian Army. Then in response to the Cambodiangovernment’s request for military assistance, starting in late April to earlyMay 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces launched a major groundoffensive into eastern Cambodia. The main U.S. objective was to clear theregion of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong in order to allow the planned Americandisengagement from the Vietnam War to proceed smoothly and on schedule. The offensive also served as a gauge of the progress of Vietnamization, particularlythe performance of the South Vietnamese Army in large-scale operations.

In the nearlythree-month successful operation (known as the Cambodian Campaign) which lasted until July 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces,which at their peak numbered over 100,000 troops, uncovered several abandonedmajor Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases and dozens of underground storagebunkers containing huge quantities of materiel and supplies. In all, American and South Vietnamese troopscaptured over 20,000 weapons, 6,000 tons of rice, 1,800 tons of ammunition, 29tons of communications equipment, over 400 vehicles, and 55 tons of medicalsupplies. Some 10,000 Viet Cong/North Vietnamese were killed in the fighting,although the majority of their forces (some 40,000) fled deeper into Cambodia. However, the campaign failed to achieve oneof its objectives: capturing the Viet Cong/NLF leadership COSVN (Central Office for South Vietnam). The Nixon administration also came underdomestic political pressure: in December 1970, and U.S. Congress passed a lawthat prohibited U.S. ground forces from engaging in combat inside Cambodia andLaos.

Before theCambodian Campaign began, President Nixon had announced in a nationwidebroadcast that he had committed U.S.ground troops to the operation. Withindays, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out inthe United States,with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio,National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four peopleand wounding eight others. This incidentsparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across thecountry. Anti-war sentiment already wasintense in the United Statesfollowing news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My LaiMassacre, where U.S. troopson a search and destroy mission descended on My Laiand My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including womenand children.

Americanpublic outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officiallytitled: United States– Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense),a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked tothe press. The Pentagon Papers showedthat successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American peopleregarding U.S. involvementin Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop thedocument’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. SupremeCourt subsequently decided in favor of the NewYork Times and publication continued, and which was also later taken up bythe Washington Post and othernewspapers.

As in Cambodia, the U.S.high command had long desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logisticalportion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail systemlocated there. But restrained by Laos’official neutrality, the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombingcampaigns in eastern Laos and intelligence gathering operations (the latterconducted by the top-secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies andObservations Group, MACV-SOG that involved units from Special Forces,Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. Air Force, and CIA) there.

The successof the Cambodian Campaign encouraged President Nixon to authorizea similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited Americanground troops from entering Laos,South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho ChiMinh Trail, with U.S. forces only playing a supporting role (andremaining within the confines of South Vietnam). Theoperation also would gauge the combat capability of the South Vietnamese Armyin the ongoing Vietnamization program.

InFebruary-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the South Vietnamese Army, (some ofwhom were transported by U.S.helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launchedOperation Lam Son 719 intosoutheastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the SouthVietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, astrategic logistical hub of the Ho Chi Minh Traillocated 25 miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The main South Vietnamese column was stoppedby heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some 15 milesfrom the border. North Vietnameseforces, initially distracted by U.S.diversionary attacks elsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the SouthVietnamese, and counterattacked. NorthVietnamese artillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several SouthVietnamese firebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S.air transport operations. By early March1971, the attack was called off, and with the North Vietnamese intensifyingtheir artillery bombardment, the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into achaotic retreat and a desperate struggle for survival. The operation was a debacle, with the SouthVietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% of their tanks, 50% of theirarmored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces; North Vietnamese casualtieswere 2,000 killed. American planes weresent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor, transports, and equipment toprevent their capture by the enemy. U.S.air losses were substantial: 84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168helicopters destroyed and 618 damaged.

Buoyed bythis success, in March 1972, North Vietnamlaunched the Nguyen Hue Offensive (called the Easter Offensive in the West),its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam, using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armoredvehicles. By this time, South Vietnameseforces carried practically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soonscheduled to leave. North Vietnameseforces advanced along three fronts. Inthe northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and capturedthe northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a SouthVietnamese counterattack, supported by U.S. air firepower, including B-52bombers, recaptured most of the occupied territory, including Quang Tri, nearthe northern border. In the CentralHighlands front, the North Vietnamese objective to advance right through tocoastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnam in two, failed to break through toKontum and was pushed back. In thesouthern front, North Vietnamese forces that advanced from the Cambodian bordertook Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, but were repulsed at An Loc because of strong SouthVietnamese resistance and massive U.S. air firepower.

To furtherbreak up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April 1972, U.S. planes includingB-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train, launched bombing attacks mostlybetween the 17th and 19th parallels in North Vietnam,targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plants andindustrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads, bridges,and railroad tracks. In May 1972, thebombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, where American planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval minesoff the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

October 11, 2021

October 11, 1954 – First Indochina War: France completes its withdrawal from North Vietnam at the 17th Parallel

From October 8–11, 1954, Francewithdrew its forces from North Vietnam to below the 17thParallel to the south, as set out in the Geneva Accords signed on July 21,1954. A stipulation in the Accords established a “provisional militarydemarcation line” at the 17th Parallel with a 3-mile widedemilitarized zone (DMZ) on each side of the demarcation line to separate theopposing forces of the French Union forces and the North Vietnamese communists,the Viet Minh. The Accords imposed a ceasefire, to be monitored by theInternational Control Commission comprising contingents from Canada, Poland,and China.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Aftermath By thetime of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war,and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and anhonorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at homeshowed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorablewithdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, oneday after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the majorpowers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and theIndochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states,Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (theGeneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolvethe crisis in the Korean Peninsula in theaftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended onJune 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, onJuly 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and theDRV, which divided Vietnaminto two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed bythe DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to servemerely as a provisional military demarcation line, and not as a political orterritorial boundary. The French andtheir allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone,while the Viet Minh in the southern zone departed and moved to the northernzone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructionsfrom the DRV). The 17th parallel wasalso a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 dayswhere Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on eitherside of the line. About one millionnortherners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upperclasses consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communistpoliticians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, thismass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) andState of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundredsof ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passageto Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north tosouth. Some 100,000 southerners, mostlyViet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northernzone. A peacekeeping force, called theInternational Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada,and Poland,was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also weresigned for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of theGeneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21,1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and thereunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed thisDeclaration. Both the State of Vietnamand the United Statesdid not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the lattertaking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize theDeclaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minhcontrolled a majority of Vietnam’sterritory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized Frenchforces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing toapparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefieldposition) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien BienPhu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held anoverwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, theSoviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the warmight prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of theFrench; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed toachieve a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-Franceregime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue thewar, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnamunder the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed tomaterialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to beimplemented. The Viet Minh proposedforming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States,seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under UnitedNations (UN) oversight. The U.S.government’s greatest fear was a communist victory at the polls; U.S. PresidentEisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho ifelections were held. The State ofVietnam also opposed holding the reunification elections, stating that as ithad not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in thereunification elections; it also declared that under the repressive conditionsin the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were notheld, and Vietnamremained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonlyknown as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as theRepublic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de factoseparate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed bythe Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnamsupported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, Francepulled out its last troops from Vietnam;some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to theState of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw thepolitical consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launchedrepressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens ofthousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned inlabor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnamfirmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed asPrime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and thereligious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of whichmaintained powerful armed groups. InApril-May 1955, sections of central Saigonwere destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyenmilitia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine theState of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supportedestablishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration ofthe monarchy as desired by Bao Dai. Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98%of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. OnOctober 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republicof Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam),with himself as its first president. Itspredecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the VietMinh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading tothousands being executed or imprisoned. Early on, militarily weak South Vietnamwas promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of PrimeMinister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist,as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weaponsarrived, followed shortly by U.S.military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South VietnameseArmy. The U.S. government also endeavored toshore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternativeto the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, andDiem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies thatfavored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lowerpeasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’spolicies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam,with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, takingplace. Then in 1959, North Vietnam,frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, andin response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it wasresuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States)in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic SecondIndochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War.

October 10, 2021

October 10, 1938 – Prelude to World War II: Czechoslovakia withdraws from the Sudetenland

In late March 1938, while Germany wasyet in the process of annexing Austria, another conflict, the “SudetenlandCrisis” occurred,where ethnic Germans, who formed the majority population in the Sudeten regionof Czechoslovakia, demanded autonomy and the right to join the Nazi Party. Hitler supported these demands, citing theSudeten Germans’ right to self-determination. The Czechoslovak government refused, and in May 1938, mobilized for war.In response, Hitler secretly asked the German High Command to prepare for war,to be launched in October 1938. Britain and France,anxious to avoid war at all costs by not antagonizing Hitler (a policy calledappeasement), pressed Czechoslovakiato yield, with the British even stating that the Sudeten Germans’ demand forautonomy was reasonable. In earlySeptember 1938, the Czechoslovak government agreed to the demands. Then when civilian unrest broke out in theSudetenland which the Czechoslovakian police quelled, in mid-September 1938, afurious Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland be ceded to Germany in order to stop thesupposed slaughter of Sudeten Germans. Under great pressure from Britainand France, on September 21,1938, the Czechoslovak government relented, and agreed to cede the Sudetenland. Butthe next day, Hitler made new demands, which Czechoslovakia rejected and again mobilizedfor war. In a frantic move to avert war,the Prime Ministers of Britainand France, NevilleChamberlain and Edouard Daladier, respectively, togetherwith Mussolini, met with Hitler, and on September 29, 1938, the four men signedthe Munich Pact,where the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany. Two days later, Czechoslovakiaaccepted the fait accompli, knowingit would not be supported by Britainand France in a war with Germany. In succeeding months, Czechoslovakia disintegrated as a sovereignstate: the Slovak region separated, aligning with Germanyas a puppet state; other regions were annexed by Hungaryand Poland; and in March1939, the rest of the Czech portion of the country was occupied by Germany.

(Taken from Events Leading up to War in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Hitlerand Nazis in Power In October 1929, the severe economiccrisis known as the Great Depression began in the United States, and then spread outand affected many countries around the world. Germany, whoseeconomy was dependent on the United States for reparations payments andcorporate investments, was badly hit, and millions of workers lost their jobs,many banks closed down, and industrial production and foreign trade droppedconsiderably.

The Weimar government weakened politically, asmany Germans turned to radical ideologies, particularly Hitler’s ultra-rightwing nationalist Nazi Party, as well as the German Communist Party. In the 1930 federal elections, the Nazi Partymade spectacular gains and became a major political party with a platform ofimproving the economy, restoring political stability, and raising Germany’s international standing by dealing withthe “unjust” Versaillestreaty. Then in two elections held in1932, the Nazis became the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament),albeit without gaining a majority. Hitler long sought the post of German Chancellor, which was the head ofgovernment, but he was rebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg[1],who distrusted Hitler. At this time,Hitler’s ambitions were not fully known, and following a political compromise byrival parties, in January 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler asChancellor, with few Nazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power,and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

On the night of February 27, 1933, firebroke out at the Reichstag, which led to the arrest and execution of a Dutcharsonist, a communist, who was found inside the building. The next day, Hitler announced that the firewas the signal for German communists to launch a nationwide revolution. On February 28, 1933, the German parliamentpassed the “Reichstag Fire Decree” whichrepealed civil liberties, including the right of assembly and freedom of thepress. Also rescinded was the writ ofhabeas corpus, allowing authorities to arrest any person without the need topress charges or a court order. In thenext few weeks, the police and Nazi SA paramilitary carried out a suppressioncampaign against communists (and other political enemies) across Germany,executing communist leaders, jailing tens of thousands of their members, andeffectively ending the German Communist Party. Then in March 1933, with the communists suppressed and other partiesintimidated, Hitler forced the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act,which allowed the government (i.e. Hitler) to enact laws, even those thatviolated the constitution, without the approval of parliament or thepresident. With nearly absolute power,the Nazis gained control of all aspects of the state. In July 1933, with the banning of politicalparties and coercion into closure of the others, the Nazi Party became the solelegal party, and Germanybecame de facto a one-party state.

At this time, Hitler grew increasinglyalarmed at the military power of the SA, particularly distrusting the politicalambitions of its leader, Ernst Rohm. On June 30-July 2, 1934, on Hitler’s orders,the loyalist Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel;English: Protection Squadron) and Gestapo (Secret Police) purged the SA,killing hundreds of its leaders including Rohm, and jailing thousands of itsmembers, violently bringing the SA organization (which had some three millionmembers) to its knees. The purgebenefited Hitler in two ways: First, he became the undisputed leader of theNazi apparatus, and Second and equally important, his standing greatlyincreased with the upper class, business and industrial elite, and Germanmilitary; the latter, numbering only 100,000 troops because of the Versaillestreaty restrictions, also felt threatened by the enormous size of the SA.

In early August 1934, with the death ofPresident Hindenburg, Hitler gained absolute power, as his Cabinet passed a lawthat abolished the presidency, and its powers were merged with those of thechancellor. Hitler thus became both German head of state and headof government, with the dual roles of Fuhrer (leader) and Chancellor. As head of state, he also was SupremeCommander of the armed forces, making him absolute ruler and dictator of Germany.

In domestic matters, the Nazigovernment made great gains, improving the economy and industrial production,reducing unemployment, embarking on ambitious infrastructure projects, andrestoring political and social order. Asa result, the Nazis became extremely popular, and party membership grewenormously. This success was broughtabout from sound policies as well as through threat and intimidation, e.g.labor unions and job actions were suppressed.

Hitler also began to impose Nazi racialpolicies, which saw ethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising“super-humans” (Ubermensch),while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered“sub-humans” (Untermenschen);also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-based groups, i.e. communists,liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah’sWitnesses, etc. Nazi lebensraum (“livingspace”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russia called for eliminating theSlavic and other populations there and replacing them with German farm settlersto help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-year German Empire.

In Germanyitself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws inSeptember 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the localJews, stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment andeducation, revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and sociallife, disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring themundesirables in Germany. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews left Germany. Hitler blamed the Jews (and communists) forthe civilian and workers’ unrest and revolution near the end of World War I,ostensibly that had led to Germany’sdefeat, and for the many social and economic problems currently afflicting thenation. Following anti-Nazi boycotts inthe United States, Britain, and other countries, Hitler retaliatedwith a call to boycott Jewish businesses in Germany, which degenerated intoviolent riots by SA mobs that attacked and killed, and jailed hundreds of Jews,looted and destroyed Jewish properties, and seized Jewish assets. The most notorious of these attacks occurredin November 1938 in “Kristallnacht”(Crystal Night), where in response to the assassination of a German diplomat bya Polish Jew in Paris, the Nazi SA and civilian mobs in Germany went on aviolent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews, jailing tens of thousands of others,and looting and destroying Jewish homes, schools, synagogues, hospitals, andother buildings. Some 1,000 synagogueswere burned, and 7,000 businesses destroyed.

In foreign affairs, Hitler, like mostGermans, denounced the Versaillestreaty, and wanted it rescinded. In1933, Hitler withdrew Germanyfrom the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva,and in October of that year, from the League of Nations, in both casesdenouncing why Germanywas not allowed to re-arm to the level of the other major powers.

In March 1935, Hitler announced thatGerman military strength would be increased to 550,000 troops, militaryconscription would be introduced, and an air force built, which essentiallymeant repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles and the start of full-scalerearmament. In response, Britain, France,and Italyformed the Stresa Front meant to stop further German violations, but thisalliance quickly broke down because the three parties disagreed on how to dealwith Hitler.

Italy,after being denounced by the League of Nations and slapped with economic sanctions after itsinvasion of Ethiopia,switched sides to Germany. Mussolini and Hitler signed a series ofagreements that soon led to a military alliance. Meanwhile, Britainand France continued theirindecisive foreign policies toward Germany. In March 1936, in a bold move, Hitler senttroops to the Rhineland, remilitarizing the region in another violation of the Versailles treaty, but metno hostile response from the other powers. Hitler justified this move as a defensive response to the recentlyconcluded French-Soviet mutual assistance pact, which he accused the twocountries of encircling Germany,a statement that drew sympathy from some British politicians.

Nazi ideology called for unification ofall Germanic peoples into a Greater German Reich. In this context, Hitler had long sought toannex Austria, whose indigenouspopulation was German, into Germany. An annexation attempt in 1934 was foiled by Italianintervention, with Mussolini determined to go to war if Germany invaded Austria. But by 1938, German-Italian relations hadwarmed and were moving toward a military alliance. With Britainand France watching by, inMarch 1938, Hitler put political pressure on Austria, and with the threat ofinvasion, forced the Austrian government to resign, and cede power to theAustrian Nazi Party. Within days, thelatter relinquished Austrian independence to Germany,and German troops occupied Austria. In a Nazi-controlled plebiscite held in April1938, an improbable 99.7% of Austrians voted for “Anschluss”(political union) with Germany.

[1] Hindenburg achieved worldwide fame in World War I as Germany’sChief of the General Staff

October 9, 2021

October 9, 1970 – Cambodian Civil War: The Khmer Republic is proclaimed

On October 9, 1970, the Khmer Republic was proclaimed in Cambodiawith General Lon Nol becoming the country’s head of state. Earlier in March1970, Lon Nol had led a coup in the National Assembly that voted to oust thereigning head of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk. The formation of the republicalso ended the Kingdom of Cambodia. Lon Nol’sright-wing government was backed by the United States, and sided with South Vietnam against North Vietnam in the ongoingVietnam War. Lon Nol also reversed Sihanouk’s tolerant policy of allowing North Vietnam to occupy large sections ofCambodian territory in its war against South Vietnam. As such, he demanded that North Vietnamesetroops leave the country.

The emergence of the Khmer Republic greatly alarmed North Vietnam,leading to the rise of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (South Vietnamese rebelsof the National Liberation Front) in Cambodian-occupied areas, as well asincreasing support for the Cambodian communist guerrilla group, the KhmerRouge.

(Taken from Cambodian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

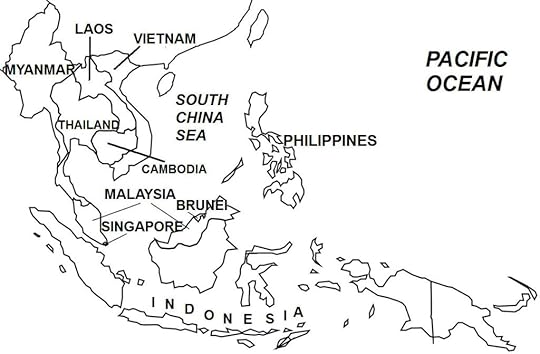

Background Between1970 and 1975, the U.S.-backed government in Cambodia fought a civil war againstthe Khmer Rouge, a Cambodian insurgent movement that wanted to establish acommunist regime in the country. TheKhmer Rouge’s victory in the war marked the rise into power of its leader, PolPot, who would engineer one of the bloodiest genocides in history. The civil war formed a part of the complexgeopolitical theaters of tumultuous Indo-China during the first half of the1970s, more particularly in reference to the Vietnam War which greatly affectedthe security climates of adjacent countries, including Cambodia (Map 1).

In 1970, serious economic problems in Cambodia prompted the military to overthrowPrince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’sruling monarch, whose faulty policies led to widespread discontent among thepeople. Prince Sihanouk, althoughextremely popular and revered as a semi-deity by Cambodians, applied acalculating but dangerous foreign policy of playing up the superpowers in orderto get the best deal for Cambodia,and still maintain neutrality.

Years earlier, Prince Sihanouk willingly had receivedmilitary and financial assistance from the United States. But in 1965, after deciding that communismultimately would prevail in Indo-China, he opened diplomatic relations with China and North Vietnam. Furthermore, he accepted military andeconomic support from North Vietnam. In return, he allowed the North Vietnamese Army to use sections ofeastern Cambodia in its waragainst South Vietnam.

October 8, 2021

October 8, 1973 – Yom Kippur War: Israeli forces suffer heavy losses in armor in a failed counter-attack

War in the Sinai In the afternoon ofOctober 6, 1973, over 200 planes of the Egyptian Air Force attacked Israeliairbases, missile and artillery positions, and radar facilities in the Sinai Peninsula. Simultaneously, 2,000 artillery gunspositioned on the western side of the Suez Canal opened fire on Israeli positions across thewaterway. Israel’sfrontline defenses consisted of a massive sand wall that ran the whole length(except along the Great Bitter Lake)of the Suez Canal (Map 13). The sand wall reached a height of up to 80feet and a slope of up to 65 degrees, which the Israelis considered could bebreached only in 24 to 48 hours, long enough for Israeli Armed Forces to reactand turn back the invasion. Behind thesand wall were the Israeli forward positions, which consisted of 22fortifications positioned at different points along the entire length of the Suez Canal. Minefields and barbed wire fences protected the approaches to thefortifications. Armored, artillery, andair defenses constituted the back end support for the fortifications.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Aided by the artillery fire, Egyptianassault units crossed the Suez Canal in raftsand clambered over the sand embankment on the other side to confront the Israeliforward positions. Egyptian Armyengineering crews then used powerful water pumps to blast away the sand wall at80 different points. Within two hours,breaches were made at five sections. Nine hours after the start of the invasion, tens of thousands ofEgyptian soldiers, as well as hundreds of tanks and armored vehicles, begancrossing the channel on bridging equipment.

The invasion caught the Israelis bysurprise. The Israeli Air Force sentplanes to the front, only to be knocked out by Egyptian SAM (surface-to-air)batteries positioned across the Suez Canal. Israeli tanks in the Sinai garrison also wentinto action but on October 8, suffered heavy losses from Egyptian anti-tankinfantry units. Israeli forwardpositions collapsed under the weight of intense Egyptian artillery fire andground assaults. Some 200 Israelisoldiers surrendered.

Over the next few days, the Egyptiansconsolidated and expanded their bridgeheads. The Egyptian Second and Third Armies, respectively, took up positionsnorth and south of the Suez Canal. By October 10, they had advanced up to eightkilometers into the Sinai. By then, thebattle lines had settled. The Israelislaunched counterattacks which were largely ineffective, while the Egyptians didnot venture away from the umbrella protection of their SAM batteries. Israel had called for a generalmobilization of its forces, and infantry and armored units were being rushed tothe front lines.

Egypt hadachieved its war objective – score a limited victory to be used to negotiatethe end of the conflict. From October 10to 13, no major battles were fought in the Sinai Peninsula. The Soviet Union airlifted large quantitiesof war supplies to Egypt(and Syria)to replace the huge inventories that had been consumed or lost. Israelalso experienced a considerable drain in its arsenals and hinted to usingnuclear weapons, which prompted the United States to begin sendinglarge amounts of weapons to the Jewish state.

October 7, 2021

October 7, 1991 – Croatian War of Independence: Yugoslav planes attack Zagreb

On October 7, 1991, Yugoslav Air Force planes attacked anumber of targets in the Croatian capital Zagreb,the most significant being the Banski dvori, the official residence of thePresident of Croatia. Inside the building at the time of the raid were CroatianPresident Franjo Tudman, Yugoslavian President Stjepan Mesic, and YugoslavianPrime minister Ante Markovic, all of whom were not injured in the attack.President Tudman laid the blame for the attacks on the Yugoslav military, butthe latter denied any involvement, instead accusing the Croatians of stagingthe attacks as a ruse. The following day, October 8, the three-month moratoriumon Croatian independence (Croatia had declared independence on June 7, 1991)lapsed, and Croatia cut allties with Yugoslavia.During the interim period, increasing tensions had broken out into fighting inthe Croatian War of Independence.

(Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background By thelate 1980s, Yugoslavia wasfaced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnicpopulations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”,separate article). Nationalism particularlywas strong in Croatia and Slovenia,the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assemblyof the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, overdisagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to theparty and the central government. Thenin the first multi-party elections in Croatiaheld in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running acampaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatiaand a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supportedTudjman, because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’snational government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and mostpowerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament wasformed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed inDecember 1990. Then in a referendum heldin May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians votedoverwhelmingly in support of independence. On June 25, 1991, Croatia,together with Slovenia,declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’stotal population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in therepublic. As Croatiaincreasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbsbecame alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry outpersecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Naziultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, andGypsies during World War II. As aresult, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias aswell as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia(northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, inFebruary 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for thepolitical and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbiaand Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed toseparate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in theirstatus in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed theCroatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorialintegrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed thatcalled for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is theacronym for Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika. Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed intoseparate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO EasternSlavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia). (Map 17 showslocations in Croatiawhere ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held inAugust 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) forSerbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Thenafter a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs votedunanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina governmentdeclared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified stateterritory of the Republic of Serbia”.