Daniel Orr's Blog, page 48

October 6, 2021

October 6, 1973 – Yom Kippur War: Egypt and Syria begin offensives against Israel

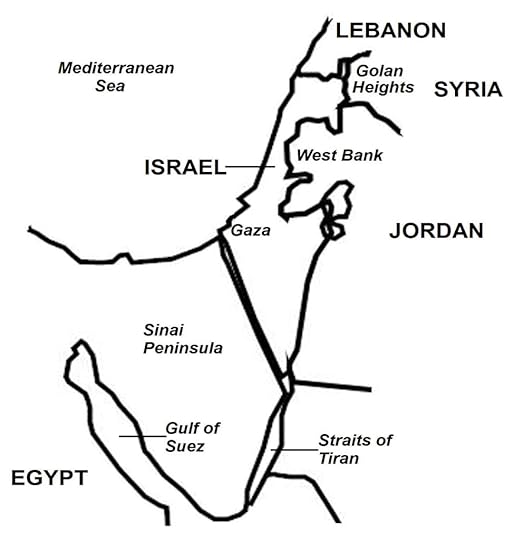

On October 6, 1973, Egyptand Syria launchedcoordinated offensives against Israel-occupied Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, respectively, starting the Yom Kippur War.Over 200 Egyptian war planes took to the air into the Sinai, striking at Israelairbases, missle batteries, artillery positions, radar installations, and commandcenters. Then under cover of an artillery barrage, 32,000 Egyptian troopscrossed the Suez Canal into the eastern bankof the Sinai.

Simultaneous with the Egyptian attack, Syria launched amassive offensive into the Golan Heights (which Israel had captured, togetherwith the Sinai Peninsula and West Bank, during the Six Day War), which was onlylight defended. The initial Syrian forces of three infantry divisionscomprising 28,000 troops, 800 tanks, and 600 artillery pieces, were joined thenext day by two armoured divisions. The initial Israeli defense forces in the Golan Heights consisted only of brigade-size formationsand supporting units comprising 3,000 troops, 180 tanks, and 60 artillerypieces.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background Withits decisive victory in the Six-Day War (previous article) in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula andGaza Strip from Egypt, theGolan Heights from Syria,and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights wereintegral territories of Egyptand Syria,respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, togetherwith other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”,that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant thatonly armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula andGolan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently wasnot received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egyptcarried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and governmenttargets in the Sinai. In what is nowknown as the “War of Attrition”, Egyptwas determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israelto withdraw from the Sinai. By way ofretaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria,Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel,and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly becameinvolved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israeland Egyptto agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passedaway. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President AnwarSadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchlyhostile to Israel,President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeliconflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations(UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign apeace treaty with Israeland recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meirrefused to negotiate. President Sadat,therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging theIsraelis from the Sinai. He decided thatan Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israelto see the need for negotiations. Egyptbegan preparations for war. Largeamounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, butineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number ofruses. The Egyptian Army constantlyconducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoriceventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the truestrength of its armed forces. Thegovernment also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its warequipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated militaryhardware. Furthermore, when PresidentSadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egyptin July 1972, Israelbelieved that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakenedseriously. In fact, thousands of Sovietpersonnel remained in Egyptand Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syriancounterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’sintelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the dateof the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbersof Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeligovernment called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire IsraeliAir Force. However, many top Israeliofficials continued to believe that Egyptand Syriawere incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were justanother army exercise. Israeli officialsdecided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War)to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur(which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, whenmost Israeli soldiers were on leave.

October 5, 2021

October 5, 1963 – Sand War: Morocco and Algeria negotiate to resolve their border conflict

On October 5, 1963, negotiators from Morocco and Algeriamet at Oujda totry and resolve the border conflict. However, both sides remained inflexible,with Morocco continuing tolay claim to areas within Algerian control, and Algeria rejecting this claim. Consequently, negotiations ended in failure.

(Taken from Sand War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 4)

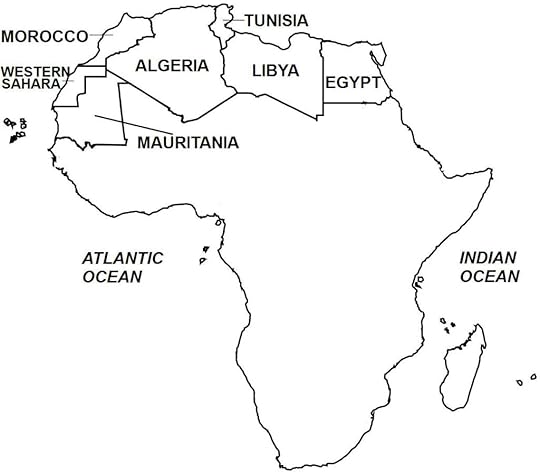

Background In1956, Morocco regained itsindependence, ending 44 years as a protectorate under France and Spain. Six years later, in 1962, Algeria, Morocco’seastern neighbor, also achieved statehood from France after prevailing in itscolonial war of independence. Nowsovereign states, Moroccoand Algeriafaced a crisis: a contentious border issue.

The origin of the border crisisgoes back to more than a century earlier, to 1830, when France invaded and captured Algiers, ending Ottoman rule and (ultimately)influence in the region. The Frenchgained full control during the rest of the 19th century and into the20th century, gradually expanded south, east, and west and addedmore territory into what ultimately would form French Algeria.

In 1842, the French colonialgovernment tried to negotiate a common border with the Sultanate of Morocco,its western neighbor and an independent political entity. The Moroccan sultan demurred, however. Then in 1844, war broke out between France and Morocco because of the Moroccansultan’s support for an Algerian uprising against French rule. In this war, known as the FirstFranco-Moroccan War, the French decisively defeated the Moroccans and in theTreaty of Tangiers, signed in October 1844 and later the Treaty of LallaMaghnia, signed in March 1845, the two sides ended the war. Furthermore, the latter treaty was significantin that France and Moroccoagreed to a partial demarcation of their border, i.e. from the coast to TenietSassi, a distance of 100 miles. Nophysical demarcation was carried out further south, which now formed part ofthe barren, thinly populated Sahara Desert; instead, the two sides agreed that the areasinhabited by tribes that traditionally recognized the Moroccan sultan’ssovereignty formed part of Morocco,while those tribes and their lands associated under the former Ottoman rule in Algiers belonged to French Algeria. Some of these tribes, however, were nomadicor had undefined territorial ranges, rendering border demarcation impossible tocarry out. French expansion deep intothe Sahara also brought regions historically associated with Moroccan influenceor sovereignty (e.g. Touat, Gourara, and Tidikelt, which are now located inpresent-day central Algeria)into the realm of French Algeria.

Figure 11. Current map of North Africa.

Meanwhile, as a result of France’s colonial expansion into western Africa,in April 1904, Britain and France signed the Entente Cordiale, an agreementwhere the British agreed to cede control of Moroccoto the French (in exchange for the French recognizing British sovereignty over Egypt). The agreement also recognized Spain’s historical sphere of influence over Morocco. In October of that year, France and Spainagreed on a delineation of zones over Moroccowhich finally resulted in the establishment of a French protectorate over Moroccoin March 1912. Then in November 1912, France handed areas of Morocco to Spain,with the latter establishing a protectorate over these areas: a northern zonearound Ceuta and Melilla,and a southern zone centered at Cape Juby (Figure 12). As a protectorate, Morocco ceded control of itsforeign affairs initiatives but remained a sovereign state according tointernational law.

In 1912, shortly afterestablishing a protectorate over Morocco, France undertook a demarcation of itsAlgerian colony for administration purposes, the land survey leading to theestablishment of the Varnier Line (French: Ligne Varnier, named after MauriceVarnier, French High Commissioner for Eastern Morocco) that extended the“border” from Teniet Sassi south to Figueg (which remained with Morocco),turned west to include Colomb-Bechar, Kenadza, and Abdla as part of FrenchAlgeria, and then turned south to an undelineated “uninhabited desert”. In the 1920s, French authorities held anumber of conferences to delineate the limits of protectorate Morocco and colonial Algeria, but these all failed toyield definitive results. In 1929, theFrench published the Confinsalgéro-marocains, which delineatedshared security and administrative jurisdictions between Morocco and Algeria along designated operationallimits (Limite opérationnelle). In 1934, France carried out another demarcation surveyfor administration purposes that included the Draa Valley,producing the Trinquet Line (French: Ligne Trinquet).

France intended some of these surveys to be used foradministrative purposes and others to establish territorial limits, furtheringthe confusion; moreover, the latter maps that were released ran contradictoryto earlier maps and sometimes went against other international treaties. However, the French established control inareas inside the survey lines, which ultimately became crucial in the borderdispute in the post-independence period.

Shortly after World War IIended in 1945, a wave of nationalism swept across the colonized peoples ofAfrica and Asia. In Morocco,an independence movement led by the ultra-nationalist Istiqlal Party gainedwide popular support for self-determination and to end France’s protectorate over Morocco. In April 1956, Mohammed V, the Moroccansultan, succeeded in convincing Franceand Spainto end their protectorates, thus regaining full independence for hiscountry. Now independent, Moroccoestablished a constitutional monarchy, with broad powers vested on the sultan(in 1957, Mohammed V assumed the title of king). The monarchy was conservative, right-wing,and anti-communist, and was aligned with France,the United States,and the Western powers in the Cold War.

Meanwhile in Algeria, France was fighting a bitter war ofindependence against Algerian nationalists led by the National Liberation Front(FLN; French: Frontde Libération Nationale). In 1952, when Morocco’sstruggle for complete self-determination was underway, France once more redrew theadministrative line, declaring that the territory extending from Colomb-Becharto Tindouf was part of French Algeria. The French particularly were interested in Tindouf, where commercialquantities of iron ore were discovered recently and the prospect of finding oiland natural gas reserves were luring French investors. In 1956, however, when the Algerianindependence war was raging and the now independent Moroccowas aligned with France and the West, the French government offered Moroccansultan Hassan II the territorial transfer of Colomb-Bechar and Tindouf to Morocco in exchange for the Moroccan government’sending its support for Algerian nationalist guerillas who operated out of Morocco. The Moroccan monarch turned down the offer,however, saying that he would deal with the Algerian nationalists directly.

In July 1961, the Moroccangovernment and the Algerian revolutionary government-in-exile (called the Gouvemement Provisoire de la République

Algérienne, or GPRA, based in Cairo Egypt)did reach a tentative agreement: Moroccowould respect independent Algeria’sterritorial integrity, but the border would be negotiated later throughbilateral talks. The following year,1962, Algeriagained its independence. In a briefpolitical power struggle that followed, the moderate GPRA was pushed aside anda hard-line regime under President Ahmed Ben Bella was established.

Morocco now attempted to open the border issue with Algeria,particularly eyeing regions that historically recognized the authority of orwere associated with the ancient Moroccan Sultanate but had become part ofFrench Algeria during the colonial period. Instead, the Ben Bella regime replied that independent Algeria, as successor state of French Algeria,legally inherited and owned all territories of the former colony; in effect,for Algeria,the border was non-negotiable.

Morocco now prepared for war. Apart from being motivated to reclaim historical Moroccan lands andrealize potential wealth from natural resources (particularly in the Tindoufregion), King Hassan II saw the coming conflict as a means to prop up and evensave his hold on power. His governmentfaced accusations of corruption and incompetence. The political opposition, led by two leftistparties, the Istiqlal Party and the National Union of Popular Forces (UNFP;French: Union Nationale des Forces

Populaires) enjoyed broad popular support among the generalpopulation that was impoverished and largely disenfranchised by thegovernment. Many Moroccans also lookedfavorably to the leftist Algerian government, with its socialist policies thatcontrasted with the conservative, right-wing Moroccan monarchy, leading to theemergence of many left-wing Moroccan clandestine organizations. In turn, King Hassan II repressedhigh-ranking members of the political opposition, accusing them of plotting tooverthrow the government. The UNFP andthe Ben Bella government maintained relations and shared a common leftistideology. For King Hassan II, a war withAlgeriawould undermine the local opposition, increase popular support for the rulingmonarchy, and turn attention away from government failings and the country’ssocio-economic problems.

Militarily for Morocco,the war couldn’t have come at a better time. Post-revolution Algeria was devastated and wrackedin chaos: a power struggle, regional uprisings, ravaged economic, public, andsocial infrastructures, etc. And allthis was not lost to the Moroccan monarch.

October 4, 2021

October 4, 1939 – World War II: The last Polish units surrender to German and Soviet forces

Facing both German and Soviet invasions, the remainingPolish units continued to engage in desperate fighting. On September 20, at Tomaszow Lubelski, theGermans annihilated two Polish armies, the Krakowand Lublin Armies. On September 22, Lwowwas taken. In Warsaw, on September 28, the Polish defenderswho had withstood relentless German air and artillery attacks, and Germanground assaults, finally capitulated after a 20-day siege, with 140,000 Polishsoldiers captured. The next day, theModlin Fortress located north of the capital also fell after two weeks offighting. Isolated Polish pockets heldoff until as late as the first week of October 1939, which were overrun, endingthe six-week war.

(Taken from Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Background InMarch 1938, with the Anschluss (political union), Germanygained control of Austria. Six months later, September 1938, with theMunich Agreement, Germanyannexed the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia;then after another six months, in March 1939, the dissolution of Czechoslovakiawas complete. German leader Adolf Hitlerhad achieved these feats using only forceful diplomacy and threats ofinvasion. He then turned his eyes on Poland,intent on using the same aggressive diplomatic tactics.

At the end of World War I, the Allies reconstituted Poland as a sovereign nation, incorporating intothe new state portions of the eastern German territories of Pomerania and Silesia, which containedmajority Polish populations. In the1920s, the German Weimar Republicsought to restore to Germanyall its lost territories, but was restrained by certain stipulations of theTreaty of Versailles, which had been imposed on Germany after World War I. Polish Pomerania was known worldwide as the“Polish Corridor”, as it allowed Polandaccess to international waters through the Baltic Sea. The German city of Danzigin East Prussia, as well as nearby areas, alsowas detached from Germany,and renamed the “Free City of Danzig”, administered by the League of Nations,but whose port, customs, and public infrastructures were controlled by Poland.

In 1933, Hitler came to power and implemented Germany’smassive rearmament program, and later began to pursue his irredentist ambitionsin earnest. Previously in January 1934,Nazi Germany and Poland hadsigned a ten-year non-aggression pact, where the German government recognizedthe territorial integrity of the Polish state, which included the Germanregions that had been ceded to Poland. But by the late 1930s, the now militarilypowerful Germanywas actively pushing to redefine the German-Polish border.

In October 1938, Germanyproposed to Poland renewingtheir non-aggression treaty, but subject to two conditions: that Danzig berestored to Germany and thatGermany be allowed to buildroad and railway lines through the Polish Corridor to connect Germany proper and East Prussia. Poland refused, and in April 1939,Hitler abolished the non-aggression pact. To Poland, Hitler wasusing the same aggressive tactics that he had used against Czechoslovakia, and that if it yielded to theGerman demands on Danzig and the Polish Corridor, ultimately the rest of Poland would be swallowed up by Germany.

Meanwhile, Britainand France, which hadpursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupationof the rest of Czechoslovakia,which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast towhat Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populatedterritories. Britainand France were nowdetermined to resist Germanydiplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britainand Franceannounced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreignaggression. Since 1921, as per theFranco-Polish Military Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Polandif that latter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only thereturn of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state andannexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansioninto Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in theseconquered areas. For Poland specifically, on August 22,1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitler had said that “the object ofthe war is … to kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children ofPolish descent or language. Only in thisway can we obtain the living space we need.” In April 1939, Hitler instructed the German military High Command tobegin preparations for an invasion of Poland, to be launched later in thesummer. By May 1939, the German militaryhad drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britainand France held high-leveltalks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military allianceagainst Germany, especiallyin light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into itsterritory in case Germanyattacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France,the Soviet Union and Germanywere also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signingof a non-aggression treaty. This treaty,which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov RibbentropPact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German ForeignMinister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European powerbalance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Sovietreprisal. The pact also included asecret protocol where Poland,Finland, Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, and Romaniawere divided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non-aggression treatyvirtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the Britishambassador that Britain mustagree to the German demands on Poland,as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front warwith major powers. But on that same day,Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, whichcontained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overturesthat Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talkswith Germany,forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

The Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) stood down, except forsome units that did not receive the new stop order and crossed into Poland,skirmishing with the Poles. These Germanunits soon withdrew back across the border, but the Polish High Command,informed through intelligence reports of massive German build-up at the border,was unaware that the border skirmishes were part of an aborted German invasion.

German negotiations with Britainand Francecontinued, but they failed to make progress. Poland had refused tonegotiate on the basis of ceding territory, and its determination wasstrengthened by the military guarantees of the Western Powers, particularly inthat if the Germans invaded, the British and French would attack from the west,and Germanywould be confronted with a two-front war.

On August 29, 1939, Germanysent Poland a set ofproposals for negotiations, which included two points: that Danzig be returnedto Germany and that aplebiscite be held in the Polish Corridor to determine whether the territoryshould remain with Poland orbe returned to Germany. In the latter, Poles who were born or hadsettled in the Corridor since 1919 could not vote, while Germans born there butnot living there could vote. Germanydemanded that negotiations were subject to a Polish official with signingpowers arriving by the following day, August 30.

Britaindeemed that the German proposal was an ultimatum to Poland, and tried but failed toconvince the Polish government to negotiate. On August 30, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop presented theBritish ambassador with a 16-point proposal for negotiations, but refused thelatter’s request that a copy be sent to the Polish government, as no Polishrepresentative had arrived by the set date. The next day, August 31, the Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski conferredwith Ribbentrop, but as Lipski had no signing powers, the talks did notproceed. Later that day, Hitlerannounced that the German-Polish talks had ended because of Poland’s refusal to negotiate. He then ordered the German High Command toproceed with the invasion of Polandfor the next day, September 1, 1939.

October 3, 2021

October 3, 1912 – United States Occupation of Nicaragua, 1912-1933: U.S. Marines attack rebel forts at the Battle of Coyotepe Hill

On October 3, U.S. Marines opened fire with two artillerypieces on the Nicaraguan rebel forts at Coyotepe and Barranca. The forts werestrategically located on a hill overlooking the Masaya railroad line nearlyhalfway between the capital Managua and Granada. The followingday, October 4, four U.S. Marine battalions stormed the forts, capturing themthat same day. Some 850 U.S. Marines were involved in the battle, assisted by100 American sailors. The rebels numbered 350 fighters inside the 2 fortsequipped with 4 artillery pieces. Casualties were: U.S. Marines – 4 killed ; Rebels –32 killed, 10 wounded.

(Taken from United States Occupation of Nicaragua, 1912-1933 – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars and Conflicts in the Americas and the Caribbean: Vol. 7)

Background The United States had sent troops to Nicaragua in1912 to intervene on the side of President Adolfo Diaz against an insurrectionby the former Minister of War General Luis Mena. The American military presencein that country would last over two decades until 1933. In many instances,Nicaragua’s political troubles prompted American intervention, such as thosethat occurred in 1847, 1894, 1896, 1898, and 1899, when U.S. forces were landedin that Central American country. Theseoccupations were brief, with American troops withdrawing once order had beenrestored, although U.S. Navy ships kept a permanent watch throughout theCentral American coastline. Theofficially stated reasons given by the United States for intervening in Nicaraguawas to protect American lives and American commercial interests in Central America. In some cases, however, the Americans wanted to give a decided advantageto one side of Nicaragua’spolitical conflict.

In 1912, the United Statesagain intervened in Nicaragua,starting an occupation of the country that would last for over two decades andwould leave a deep impact on the local population. The origin of the 1912 American occupationtraces back to the early 1900s when Nicaragua,then led by the Liberals, offered the construction of the NicaraguaCanal to Germanyand Japan. The NicaraguaCanal was planned to be a shippingwaterway that connects the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean through the Caribbean Sea.

The Liberals wanted less American involvement in Nicaragua’sinternal affairs and therefore offered the waterway’s construction to othercountries. Furthermore, the United States had decided to forgo its originalplan to build the Nicaragua Canal in favor of completing the partly-finished Panama Canal (which had been abandoned by a Frenchconstruction firm).

For the United States,however, the idea of another foreign power in the Western Hemisphere wasanathema, as the U.S.government believed it had the exclusive rights to the region. The American policy of exclusivity in theWestern Hemisphere was known as the Monroe Doctrine, set forth in 1823 byformer U.S.president James Monroe. Furthermore, theUnited States believed that Nicaragua had ambitions in Central America and therefore viewed that country as a potential source ofa wider conflict. U.S.-Nicaraguanrelations deteriorated when two American saboteurs were executed by theNicaraguan government. Consequently, theUnited States broke offdiplomatic relations with Nicaragua.

In October 1909, Nicaraguan Conservatives, backed by someLiberals, carried out a rebellion against the government. The United States threw its supportbehind the rebels. Then when therebellion spread, the United Statessent warships to Nicaraguaand subsequently, in December 1909, landed troops in Corinto and Bluefields(Map 38). More American forces arrivedin May 1910.

In August 1910, Nicaragua’s ruling governmentcollapsed, replaced by a U.S.-friendly administration consisting ofConservatives and Liberals. The United States bought out Nicaragua’s large foreign debt thathad accumulated during the long period of instability. Consequently, Nicaraguaowed the United Statesthe amount of that debt, while the Americans’ stake was raised in that troubledcountry.

Then in 1912, Nicaragua’s ruling coalition brokedown, sparking a civil war between the government and another alliance ofLiberals and Conservatives. As therebels gained ground and began to threaten Managua,Nicaragua’s capital, the United Stateslanded troops in Corinto, Bluefields, and San Juan del Sur. At its peak, the U.S.troop deployment in Nicaraguatotaled over 2,300 soldiers. Within amonth of the deployment, in October 1912, the American troops, supported byNicaraguan government forces, had defeated the rebels.

The United Statestightened its control of Nicaraguain August 1914 when both countries signed an agreement whereby the Americansgained exclusive rights to construct the Nicaragua Canal,as well as to establish military bases to protect it. The U.S.-Nicaragua treaty mostly served as adeterrent against other foreign involvement in Nicaragua,since by this time, the Americans already were operating the Panama Canal nearby.

October 2, 2021

October 2, 1941 – World War II: The German Army begins its offensive to capture Moscow

On October 2, 1941, shortlyafter the Kiev campaign ended, on Hitler’sorders, the Wehrmacht launched its offensive on Moscow. For this campaign, codenamed Operation Typhoon, the Germans assembled anenormous force of 1.9 million troops, 48,000 artillery pieces, 1,400 planes,and 1,000 tanks, the latter involving three Panzer Groups (now renamed PanzerArmies), the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th (the lattertaken from Army Group North). A seriesof spectacular victories followed: German 2nd Panzer Army, movingnorth from Kiev, took Oryol on October 3 and Bryansk on October 6, trapping 2Soviet armies, while German 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies tothe north conducted a pincers attack around Vyazma, trapping 4 Sovietarmies. The encircled Red Army forcesresisted fiercely, requiring 28 divisions of German Army Group Centerand two weeks to eliminate the pockets. Some 500,000–600,000 Soviet troops were captured, and the first of threelines of defenses on the approach to Moscowhad been breached. Hitler and the GermanHigh Command by now were convinced that Moscowwould soon be captured, while in Berlin,rumors abounded that German troops would be home by Christmas.

(Taken from Invasion of the Soviet Union – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Battle of Moscow On October 2, 1941, shortly after the Kievcampaign ended, on Hitler’s orders, the Wehrmacht launched its offensive on Moscow. For this campaign, codenamed OperationTyphoon, the Germans assembled an enormous force of 1.9 million troops, 48,000artillery pieces, 1,400 planes, and 1,000 tanks, the latter involving threePanzer Groups (now renamed Panzer Armies), the 2nd, 3rd,and 4th (the latter taken from Army Group North). A series of spectacular victories followed:German 2nd Panzer Army, moving north from Kiev, took Oryol onOctober 3 and Bryansk on October 6, trapping 2 Soviet armies, while German 3rdand 4th Panzer Armies to the north conducted a pincers attack aroundVyazma, trapping 4 Soviet armies. Theencircled Red Army forces resisted fiercely, requiring 28 divisions of German Army Group Centerand two weeks to eliminate the pockets. Some 500,000–600,000 Soviet troops were captured, and the first of threelines of defenses on the approach to Moscowhad been breached. Hitler and the GermanHigh Command by now were convinced that Moscowwould soon be captured, while in Berlin,rumors abounded that German troops would be home by Christmas.

Some Red Army elements fromthe Bryansk-Vyazma sector avoided encirclement and retreated to the tworemaining defense lines near Mozhaisk. By now, the Soviet military situation was critical, with only 90,000troops and 150 tanks left to defend Moscow. Stalin embarked on a massive campaign toraise new armies and transfer formations from other sectors, and move largeamounts of weapons and military equipment to Moscow. Martial law was declared in the city, and on Stalin’s orders, thecivilian population was organized into work brigades to construct trenches andanti-tank traps along Moscow’sperimeter. As well, consumer industriesin the capital were converted to support the war effort, e.g. an automobileplant now produced light weapons, a clock factory made mine detonators, andmachine shops repaired tanks and military vehicles.

On October 15, 1941, onStalin’s orders, the state government, communist party leadership, and Sovietmilitary high command evacuated from Moscow, and established (temporary)headquarters at Kuibyshev (present-day Samara). Stalin and a small core of officials remained in Moscow, which somewhat calmed the civilianpopulation that had panicked at the government evacuation, and initially hadalso hastened to leave the capital.

On October 13, 1941, whilemopping up operations continued at the Bryansk-Vyazma sector, German armoredunits thrust into the Soviet defense lines at Mozhaisk, breaking through afterfour days of fighting, and taking Kalinin, Kaluga, and then Naro-Fominsk(October 21) and Volokolamsk (October 27), with Soviet forces retreating to newlines behind the Nara River. The way to Moscow now appeared open.

In fact, Operation Typhoonwas by now sputtering, with German forces severely depleted and counting only30% of operational motor vehicles and 30-50% available troop strength in mostunits. Furthermore, since nearly thestart of Operation Typhoon, the weather had deteriorated, with the seasonalcold rains and wet snow turning the unpaved roads into a virtually impassableclayey morass (a phenomenon known in Russia as “Rasputitsa”, literally, “time without roads”) that brought Germanmotorized and horse traffic to a standstill. The stoppage in movement also prevented the delivery to the frontlinesof troop reinforcements, supplies, and munitions. On October 31, 1941, with weather and roadconditions worsening, the German High Command stopped the advance, this pauseeventually lasting over two weeks, until November 15. Temperatures also had begun to drop, and theGermans were yet without winter clothing and winterization supplies for theirequipment, which also were caught up in the weather-induced logistical delay.

Meanwhile, in Moscow, Stalinand the Soviet High Command took advantage of this crucial delay by hastilyorganizing 11 new armies and transferring 30 divisions from Siberia (togetherwith 1,000 tanks and 1,000 planes) for Moscow, the latter being made availablefollowing Soviet intelligence information indicating that the Japanese did notintend to attack the Soviet Far East. Bymid-November 1941, the Soviets had fortified three defensive lines around Moscow, set up artilleryand ambush points along the expected German routes of advance, and reinforcedSoviet frontline and reserve armies. Ultimately, Soviet forces in Moscowwould total 2 million troops, 3,200 tanks, 7,600 artillery pieces, and 1,400planes.

On November 15, 1941, cold,dry weather returned, which froze and hardened the ground, allowing theWehrmacht to resume its offensive. Forthe final push to Moscow, three panzer armies were tasked with executing apincers movement: the 2nd in the south, and the 3rd and 4thin the north, both pincer arms to link up at Noginsk, 40 miles east ofMoscow. Then with Soviet forces divertedto protect the flanks, German 4th Army would attack from the westdirectly into Moscow.

In the southern pincer,German 2nd Panzer Army had reached the outskirts of Tula as early as October26, but was stopped by strong Soviet resistance as well as supply shortages,bad weather, and destroyed roads and bridges. On November 18, while still suffering from logistical shortages, 2ndPanzer Army attacked toward Tulaand made only slow progress, although it captured Stalinogorsk on November22. In late November 1941, a powerfulSoviet counter-attack with two armies and Siberian units inflicted a decisivedefeat on German 2nd Panzer Army at Kashira, which effectivelystopped the southern advance.

To the north, German 3rdand 4th Panzer Armies made more headway, taking Klin (November 24)and Solnechnogorsk (November 25), and on November 28, crossed the Moscow-VolgaCanal, to begin encirclement of the capital from the north. Wehrmacht troops also reached Krasnaya Polyanaand possibly also Khimki, 18 miles and 11 miles from Moscow, respectively, marking the farthestextent of the German advance and also where German officers using binocularswere able to make out some of the city’s main buildings.

With both pincersimmobilized, on December 1, 1941, German 4th Army attacked from thewest, but encountered the strong defensive lines fronting Moscow, and was repulsed. Furthermore, by early December 1941, snowblizzards prevailed and temperatures plummeted to –30°C (–22°F) to –40°C(–40°F), and German Army Group Center, which wasfighting without winter clothing, suffered 130,000 casualties fromfrostbite. German tanks, trucks, andweapons, still not winterized, suffered operational malfunctions in the winteryconditions. Furthermore, because of poorweather prevailing throughout much of Operation Typhoon, the Luftwaffe, which had proved decisive in earlierbattles, had so far played virtually no part in the Moscow campaign.

October 1, 2021

October 1, 1991 – Croatian War of Independence: Yugoslav forces begin the Siege of Durbrovnik

On October 1, 1991, Yugoslav Army forces advanced from Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, andSerb-controlled Croatiatoward the western region of southern Dalmatia with the city of Dubrovnik as their mainobjective. The capture of the towns ofPrevlaka, Konavle, and Cavtat allowed the Yugoslavs to encircle Dubrovnik. Artillery batteries placed on the surroundingheights, together with Yugoslav Navy ships on the coastal waters, opened fireon the city, starting a seven-month siege. Yugoslav planes also conducted air strikes on Dubrovnik. International diplomatic pressures and widespread foreign media coverageof the siege eventually deterred the Yugoslav Army from carrying out a groundassault on the city.

(Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background By thelate 1980s, Yugoslavia wasfaced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnicpopulations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”,separate article). Nationalismparticularly was strong in Croatiaand Slovenia,the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assemblyof the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, overdisagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to theparty and the central government. Thenin the first multi-party elections in Croatiaheld in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running acampaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatiaand a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supported Tudjman,because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’snational government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and mostpowerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament wasformed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed inDecember 1990. Then in a referendum heldin May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians votedoverwhelmingly in support of independence. On June 25, 1991, Croatia,together with Slovenia,declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’stotal population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in therepublic. As Croatiaincreasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbsbecame alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry outpersecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Naziultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, andGypsies during World War II. As aresult, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias aswell as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia(northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, inFebruary 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for thepolitical and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbiaand Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed toseparate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in theirstatus in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed theCroatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorialintegrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed thatcalled for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is theacronym for Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika. Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed intoseparate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO EasternSlavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia). (Map 17 showslocations in Croatiawhere ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held inAugust 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) forSerbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Thenafter a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs votedunanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina governmentdeclared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified stateterritory of the Republic of Serbia”.

September 30, 2021

September 30, 1938 – Britain, France, Italy, and Germany sign the Munich Agreement, where the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany

In a frantic move to avert war, the Prime Ministers of Britain and France,Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, respectively, together withMussolini, met with Hitler, and on September 30, 1938, the four signed theMunich Pact, whereby the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany.

(Taken from Events Leading Up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background Inlate March 1938, while Germany was yet in the process of annexing Austria, anotherconflict, the “Sudetenland Crisis” occurred, where ethnic Germans, who formedthe majority population in the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia, demandedautonomy and the right to join the Nazi Party. Hitler supported these demands, citing the Sudeten Germans’ right toself-determination. The Czechoslovakgovernment refused, and in May 1938, mobilized for war. In response, Hitlersecretly asked the German High Command to prepare for war, to be launched inOctober 1938. Britainand France, anxious to avoidwar at all costs by not antagonizing Hitler (a policy called appeasement),pressed Czechoslovakiato yield, with the British even stating that the Sudeten Germans’ demand forautonomy was reasonable. In earlySeptember 1938, the Czechoslovak government agreed to the demands. Then when civilian unrest broke out in theSudetenland which the Czechoslovakian police quelled, in mid-September 1938, afurious Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland be ceded to Germany in order to stop thesupposed slaughter of Sudeten Germans. Under great pressure from Britainand France, on September 21,1938, the Czechoslovak government relented, and agreed to cede the Sudetenland. Butthe next day, Hitler made new demands, which Czechoslovakia rejected and againmobilized for war. In a frantic move toavert war, the Prime Ministers of Britainand France, NevilleChamberlain and Edouard Daladier, respectively, together with Mussolini, metwith Hitler, and on September 29, 1938, the four men signed the Munich Pact,where the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany. Two days later, Czechoslovakiaaccepted the fait accompli, knowing it would not be supported by Britain and Francein a war with Germany. In succeeding months, Czechoslovakia disintegrated as a sovereign state:the Slovak region separated, aligning with Germanyas a puppet state; other regions were annexed by Hungaryand Poland; and in March1939, the rest of the Czech portion of the country was occupied by Germany.

Hitler and Nazis inPower In October 1929, the severe economic crisis known as the GreatDepression began in the United States, and then spread out and affectedmany countries around the world. Germany, whose economy was dependent on the United Statesfor reparations payments and corporate investments, was badly hit, and millionsof workers lost their jobs, many banks closed down, and industrial productionand foreign trade dropped considerably.

The Weimargovernment weakened politically, as many Germans turned to radical ideologies,particularly Hitler’s ultra-right wing nationalist Nazi Party, as well as theGerman Communist Party. In the 1930federal elections, the Nazi Party made spectacular gains and became a majorpolitical party with a platform of improving the economy, restoring political stability,and raising Germany’sinternational standing by dealing with the “unjust” Versailles treaty. Then in two elections held in 1932, the Nazisbecame the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament), albeit withoutgaining a majority. Hitler long soughtthe post of German Chancellor, which was the head of government, but he wasrebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg , who distrustedHitler. At this time, Hitler’s ambitionswere not fully known, and following a political compromise by rival parties, inJanuary 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor, with fewNazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power,and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

On the night of February 27, 1933, fire broke out at theReichstag, which led to the arrest and execution of a Dutch arsonist, acommunist, who was found inside the building. The next day, Hitler announced that the fire was the signal for Germancommunists to launch a nationwide revolution. On February 28, 1933, the German parliament passed the “Reichstag FireDecree” which repealed civil liberties, including the right of assembly andfreedom of the press. Also rescinded wasthe writ of habeas corpus, allowing authorities to arrest any person withoutthe need to press charges or a court order. In the next few weeks, the police and Nazi SA paramilitary carried out asuppression campaign against communists (and other political enemies) across Germany,executing communist leaders, jailing tens of thousands of their members, andeffectively ending the German Communist Party. Then in March 1933, with the communists suppressed and other partiesintimidated, Hitler forced the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act, whichallowed the government (i.e. Hitler) to enact laws, even those that violatedthe constitution, without the approval of parliament or the president. With nearly absolute power, the Nazis gainedcontrol of all aspects of the state. InJuly 1933, with the banning of political parties and coercion into closure ofthe others, the Nazi Party became the sole legal party, and Germany became de facto a one-partystate.

At this time, Hitler grew increasingly alarmed at themilitary power of the SA, particularly distrusting the political ambitions ofits leader, Ernst Rohm. On June 30-July2, 1934, on Hitler’s orders, the loyalist Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel; English:Protection Squadron) and Gestapo (Secret Police) purged the SA, killinghundreds of its leaders including Rohm, and jailing thousands of its members,violently bringing the SA organization (which had some three million members)to its knees. The purge benefited Hitlerin two ways: First, he became the undisputed leader of the Nazi apparatus, andSecond and equally important, his standing greatly increased with the upperclass, business and industrial elite, and German military; the latter,numbering only 100,000 troops because of the Versailles treaty restrictions,also felt threatened by the enormous size of the SA.

In early August 1934, with the death of PresidentHindenburg, Hitler gained absolute power, as his Cabinet passed a law thatabolished the presidency, and its powers were merged with those of thechancellor. Hitler thus became bothGerman head of state and head of government, with the dual roles of Fuhrer(leader) and Chancellor. As head ofstate, he also was Supreme Commander of the armed forces, making him absoluteruler and dictator of Germany.

In domestic matters, the Nazi government made great gains,improving the economy and industrial production, reducing unemployment,embarking on ambitious infrastructure projects, and restoring political andsocial order. As a result, the Nazis becameextremely popular, and party membership grew enormously. This success was brought about from soundpolicies as well as through threat and intimidation, e.g. labor unions and jobactions were suppressed.

Hitler also began to impose Nazi racial policies, which sawethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising “super-humans” (Ubermensch),while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered“sub-humans” (Untermenschen); also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-basedgroups, i.e. communists, liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals,Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc. Nazi lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russiacalled for eliminating the Slavic and other populations there and replacingthem with German farm settlers to help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-yearGerman Empire.

In Germanyitself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws inSeptember 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the localJews, stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment andeducation, revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and sociallife, disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring themundesirables in Germany. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews left Germany. Hitler blamed the Jews (and communists) forthe civilian and workers’ unrest and revolution near the end of World War I,ostensibly that had led to Germany’sdefeat, and for the many social and economic problems currently afflicting thenation. Following anti-Nazi boycotts inthe United States, Britain, and other countries, Hitler retaliatedwith a call to boycott Jewish businesses in Germany, which degenerated intoviolent riots by SA mobs that attacked and killed, and jailed hundreds of Jews,looted and destroyed Jewish properties, and seized Jewish assets. The most notorious of these attacks occurredin November 1938 in “Kristallnacht” (Crystal Night), where in response to theassassination of a German diplomat by a Polish Jew in Paris, the Nazi SA andcivilian mobs in Germany went on a violent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews,jailing tens of thousands of others, and looting and destroying Jewish homes,schools, synagogues, hospitals, and other buildings. Some 1,000 synagogues were burned, and 7,000businesses destroyed.

In foreign affairs, Hitler, like most Germans, denounced theVersaillestreaty, and wanted it rescinded. In1933, Hitler withdrew Germanyfrom the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva,and in October of that year, from the League of Nations, in both casesdenouncing why Germanywas not allowed to re-arm to the level of the other major powers.

September 28, 2021

September 28, 1939 – World War II: Germany and the Soviet Union partition Poland

On September 28, 1939, as their joint invasion of Poland was winding down, Germany and the Soviet Union, acting on Stalin’s proposal, agreed to make changes totheir respective spheres of influence as set forth in the Molotov-Ribbentroppact. In the revised treaty, Germany relinquished to the Soviet Union itsclaim to a sphere of influence on Lithuaniain exchange for the Soviet Union relinquishing to Germanyits sphere of influence to sections of central Poland,including Warsaw and Lublin. On October 8, 1939, Germanyannexed western Poland,including Danzig, the Polish Corridor, and Silesia,and established the German-run General Governorate in the rest of theGerman-assigned territory in Poland.

(Taken from Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

The Soviet Union also annexed its share of Polishterritories, partitioning them among its subordinate states Belarus, Ukraineand Lithuania,and implementing Sovietization policies in ethnic Polish-majority regions.

In German-controlled Poland, which was extended to includeall of Poland after German forces captured the Soviet section of Poland in theearly stages of Operation Barbarossa (the German invasion of the Soviet Union)in June 1941, Nazi Germany implemented policies aimed at achieving Lebensraum,where ethnic Germans would settle in the former Polish territories which thenwould be completely Germanized politically, economically, socially, andculturally. As Lebensraum entaileddisplacing the native populations, Generalplan Ost (General Plan East) wasinitiated in a series of programs of depopulating, resettling, or otherwiseeliminating the Polish population from lands that were destined to become fullyGerman. Central to Nazi doctrine was theconcept of German racial superiority, and that German ethnic purity was to bemaintained and not tainted by the blood of races which the Nazis classified asinferior (Untermensch, or sub-human), which included Poles and other Slavicpeoples, Jews, and Roma (gypsies), among others.

The colonization and full Germanization of Polishterritories were to be accomplished in stages over many years. But of more urgency to the Germans was thefate of Polish Jews, whose eradication was determined in January 1942 throughthe euphemistically called “Final Solution”. In the aftermath of the Polish campaign, German authorities segregatedthe three million Polish Jews, who were then forced into the hundreds of Jewishghettos quickly set up across Poland. In the ensuing period, Polish and other Jewsacross Europe were transported by train tospecially constructed labor, concentration, and extermination camps where themass executions ultimately were carried out. Aside from Jews, Slavs, and Roma, Nazi extermination policies alsotargeted the physically and mentally disabled, homosexuals, politicalopponents, communists, prisoners of war, resistance fighters, and other groups.

In Poland,as a result of the German occupation, some six million Poles perished, or 20%of the total population. Of this number,three million were Jews, of whom 90% were killed.

September 27, 2021

September 27, 1940 – World War II: Germany, Italy, and Japan sign the Tripartite Pact

On September 27, 1940, Germany,Italy, and Japan signed the Tripartite Pact, amutual assistance treaty where the signatories pledged to come to the aid “ifone of the Contracting Powers is attacked by a Power at present not involved inthe European War or in the Japanese-Chinese conflict.” At this time, Europe wasalready embroiled in World War II while in Asia,the Second-Japanese War was being fought. The Pact was directed at the United States,which was then the only neutral major power, to deter its being involved in theconflicts on the Allied side. The Pact also acknowledged the pre-eminence of Germany and Italyin Europe, and Japanin “Greater East Asia”. It was to be effective for ten years, with a provisionfor negotiations for its renewal.

The Tripartite Pact was later joined by other countries: Hungary on November 20, 1940, Romania on November 23, 1940, Slovakia on November 24, 1940, Bulgaria on March 1, 1941, and Yugoslavia on March 25, 1941. Afterthe Axis invasion of Yugoslavia,upon its partition, the newly formed IndependentState of Croatia joined the Pact on June 15,1941.

The Soviet Union also entered into negotiations with Germanyto join the Tripartite Pact, even offering the latter substantial economicconcessions. However, Hitler was determined that the Soviet Union would not be allowed to join, as preparations were alreadyunderway for Operation Barbarossa.

In June 1941, after the start of the German-led invasion ofthe Soviet Union, Germanyasked Finland,which had also participated in the attack, to join the Tripartite Pact.However, the Finnish government rebuffed the offer, as its military objectivesdiffered from the Germans. Finlandalso wanted to maintain diplomatic relations with the United States and Allies.

Japanattacked Thailand onDecember 8, 1941 as a means to gain passage to invasion British Malaya and Burma.After a ceasefire was signed, Japaninvited Thailandto join the Tripartite Pact, but the latter only agreed on military cooperationwith the Japanese.

(Taken from Events Leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century- World War II in Europe: Vol. 6)

Italybefore World War II In World War I, Italy had joined the Allies under a secretagreement (the 1915 Treaty of London) in that it would be rewarded with thecoastal regions of Austria-Hungaryafter victory was achieved. But afterthe war, in the peace treaties with Austria-Hungaryand Germany, the victoriousAllies reneged on this treaty, and Italy was awarded much lessterritory than promised. Indignation swept across Italy,and the feeling of the so-called “mutilated victory” relating to Italy’sheavy losses in the war (1.2 million casualties and steep financial cost) ledto the rise in popularity of ultra-nationalist, right-wing, and irredentistideas. Italian anger over the war pavedthe way for the coming to power of the Fascist Party, whose leader Benito Mussolinibecame Prime Minister in October 1922. The Fascist government implemented major infrastructure and socialprograms that made Mussolini extremely popular. In a few years, Mussolini ruled with near absolute powers in a virtualdictatorship, with the legislature abolished, political dissent suppressed, andhis party the sole legal political party. Mussolini also made gains in foreign affairs: in the Treaty of Lausanne(July 1923) that ended World War II between the Allies and Ottoman Empire,Italy gained Libya and the Dodecanese Islands. In August 1923, Italian forces occupied Greece’sCorfu Island,but later withdrew after League of Nationsmediation and the Greek government’s promise to pay reparations.

In the late 1920s onward, Mussolini advocated grandioseexpansionism to establish a modern-day Italian Empire, which would includeplans to annex Balkan territories that had formed part of the ancient RomanEmpire, gaining a sphere of influence in parts of Central and Eastern Europe,achieving mastery over the Mediterranean Sea, and gaining control of NorthAfrica and the Middle East which would include territories stretching from theAtlantic Ocean in the west to the Indian Ocean in the east.

With the Nazis coming to power in Germanyin 1933, Hitler and Mussolini, with similar political ideologies, initially didnot get along well, and in July 1934, they came into conflict over Austria. There, Austrian Nazis attempted a coupd’état, assassinating Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss and demanding unificationwith Germany. Mussolini, who saw Austriaas falling inside his sphere of influence, sent troops, tanks, and planes tothe Austrian-Italian border, poised to enter Austriaif Germanyinvaded. Hitler, at this time stillunprepared for war, backed down from his plan to annex Austria. Then in April 1935, Italy banded togetherwith Britain and France to form the Stresa Front (signed in Stresa, Italy),aimed as a united stand against Germany’s violations of the Versailles andLocarno treaties; one month earlier (March 1935), Hitler had announced his planto build an air force, raise German infantry strength to 550,000 troops, andintroduce military conscription, all violations of the Versailles treaty.

However, the Stresa Front quickly ended in fiasco, as thethree parties were far apart in their plans to deal with Hitler. Mussolini pressed for aggressive action; theBritish, swayed by anti-war public sentiments at home, preferred to negotiatewith Hitler; and France,fearful of a resurgent Germany,simply wanted an alliance with the others. Then in June 1935, just two months after the Stresa Front was formed,Britain and Germany signed a naval treaty (the Anglo-German Naval Agreement),which allowed Germany to build a navy 35% (by tonnage) the size of the Britishnavy. Italy(as well as France) wasoutraged, as Britain wasopenly allowing Hitler to ignore the Versaillesprovision that restricted German naval size. Mussolini, whose quest for colonial expansion was only restrained by thereactions from both the British and French, saw the naval agreement as Britishbetrayal to the Stresa Front. ToMussolini, it was a green light for him to launch his long desired conquest of Ethiopia (then also known as Abyssinia). In October 1935, Italyinvaded Ethiopia,overrunning the country by May 1936 and incorporating it into newly formed Italian East Africa. In November 1935, the League of Nations, acting on a motion by Britain that was reluctantly supported by France, imposed economic sanctions on Italy, which angered Mussolini, worsening Italy’s relations with its Stresa Frontpartners, especially Britain. At the same time, since Hitler gave hissupport to Italy’s invasionof Ethiopia, Mussolini wasdrawn to the side of Germany. In December 1937, Mussolini ended Italy’s membership in the League of Nations, citing the sanctions, despite the League’s alreadylifting the sanctions in July 1936.

In January 1936, Mussolini informed the German governmentthat he would not oppose Germanyextending its sphere of influence in Austria (Germany annexed Austria inMarch 1938). And in February 1936,Mussolini assured Hitler that Italywould not invoke the Versailles and Locarno treaties if Germanyremilitarized the Rhineland. In March 1936, Hitler did just that,eliciting no hostile response from Britainor France. Then in the Spanish Civil War, which startedin July 1936, Italy and Germanyprovided weapons and troops to the right-wing Nationalist forces that rebelledagainst the Soviet Union-backed leftist Republican government. In April 1939, the Nationalists emergedvictorious, and their leader General Francisco Franco formed a fascistdictatorship in Spain.

In October 1936, Italyand Germany signed apolitical agreement, and Mussolini announced that “all other European countrieswould from then on rotate on the Rome-Berlin Axis”, with the term “Axis” laterdenoting this alliance, which included Japan as well as other minorpowers. In May 1939, German-Italianrelations solidified into a formal military alliance, the “Pact of Steel”. In November 1937, Italyjoined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which Germanyand Japan signed one yearearlier (November 1936), ostensibly only directed against the CommunistInternational (Comintern), but really targeting communist ideology and by extension,the Soviet Union. In September 1940, the Axis Powers wereformed, with Germany, Italy, and Japan signing the Tripartite Pact.

In April 1939, Italyinvaded Albania (separatearticle), gaining full control within a few days, and the country was joinedpolitically with Italyas a separate kingdom in personal union with the Italian crown. Six months later (September 1939), World WarII broke out in Europe, which took Italy completely by surprise.

Despite its status as a major military power, Italy wasunprepared for war. It had apredominantly agricultural economy, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for war-importantitems such as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind those ofother western powers. In militarycapability, Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostlyobsolete, although the Italian Navy was large, ably powerful, and possessedseveral modern battleships. Cognizant ofItalian military deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts to build up armedstrength, and by 1939, some 40% of the national budget was allocated tonational defense. Even so, Italianmilitary planners had projected that full re-armament and building up of theirforces would be completed only in 1943; thus, the unexpected start of World WarII in September 1939 came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

September 26, 2021

September 26, 1950 – Korean War: UN forces recapture Seoul

United Nations (UN) forces at Inchon soon recaptured Kimpo airfield. There, U.S.planes began to conduct air strikes on North Korean positions in and around Seoul. UN ground forces then launched athree-pronged attack on the capital. They met heavy North Korean resistance at the perimeter but sooncaptured the heights overlooking the city. On September 25, 1950, UN forces entered Seoul, and soon declared the cityliberated. Even then, house-to-housefighting continued until September 27, when the city was brought under full UNcontrol. On September 29, 1950, UNforces formally turned over the capital to President Syngman Rhee, whoreestablished his government there. Andby the end of September 1950, with remnants of the decimated North Korean Armyretreating in disarray across the 38th parallel, South Korean and UN unitsgained control of all pre-war South Korean territory.

(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

On October 1, 1950, the South Korean Army crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea along the eastern and central regions; UN forces,however, waited for orders. Four daysearlier, on September 27, 1950, President Truman sent a top-secret directive toGeneral MacArthur advising him that UN forces could cross the 38th parallelonly if the Soviet Union or China had not sent or did not intend to send forcesto North Korea.

Earlier, the Chinese government had stated that UN forcescrossing the 38th parallel would place China’s national security at risk,and thus it would be forced to intervene in the war. Chairman Mao Zedong also stated that if U.S. forces invaded North Korea, Chinamust be ready for war with the United States.

At this stage of the Cold War, the United States believed that its biggest threatcame from the Soviet Union, and that the Korean War may very well be a Sovietplot to spark an armed conflict between the United States and China. This would force the U.S. military to divert troops and resources toAsia, and leave Western Europe open to aSoviet invasion. But after muchdeliberation, the Truman administration concluded that China was “bluffing” and would not reallyintervene in Korea,and that its threats merely were intended to undermine the UN. Furthermore, General MacArthur also later(after UN forces had crossed the 38th parallel) expressed full confidence inthe UN (i.e. U.S.)forces’ military superiority – that Chinese forces would face the “greatestslaughter” if they entered the war.

On October 7, 1950, the UNGA adopted Resolution 376 (V)which declared support for the restoration of stability in the Korean Peninsula,a tacit approval for the UN forces to take action in North Korea. Two days later, October 9, UN forces, led bythe Eighth U.S. Army, crossed the 38th parallel in the west, with GeneralMacArthur some days earlier demanding the unconditional surrender of the NorthKorean Army. UN forces met only lightresistance during their advance north. On October 15, 1950, Namchonjam fell, followed two days later byHwangju.

In North Korea’s eastern coast, the U.S. X Corps madeunopposed amphibious landings at Wonsan on October 25, 1950 (with South Koreanforces having taken this port town days earlier) and at Iwon, further north, onOctober 29. On October 24, 1950, underthe “Thanksgiving Offensive” issued by General MacArthur who wanted the warended before the start of winter, UN forces made a rapid advance to the Yalu River,which serves as the China-North Korea border.

In late October 1950, UN forces clashed with the ChineseArmy, and a new phase of the war began. Earlier, in June 1950 in Beijing,Chairman Mao had declared his intention to intervene in the Korean conflict,which received strong reluctance from Chinese military leaders. But with the support of Premier Zhou Enlai,and General Peng Dehuai, (military commander of China’s northwest region, whowould be appointed to lead the Chinese forces in the Korean War), the plan forthe Chinese Army (officially called the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA) tobecome involved in Korea was approved.

On October 8, 1950, the day that UN forces crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea,Chinese forces in Manchuria (the North East Frontier Force, or NEFF) wereordered to deploy at the Yalu River in preparation to enter North Korea from the north. On October 19, 1950, the day Pyongyangfell, on Chairman Mao’s order, the NEFF crossed into North Korea. Chinese authorities called this force the“People’s Volunteer Army”, the “volunteer” designation conferring on it anon-official status in order that China would not be directlyinvolved in a war with the US/UN.

The Chinese deployment from Manchuria to Korea was carried out under strictsecrecy, and Chinese troops travelled only at night and remained camouflagedduring the day. So successful were theChinese in using secrecy and concealment that U.S.surveillance planes, even with their full control of the skies, were unable todetect the massive Chinese buildup at the Yalu River. Chinese forces soon entered North Korea.

On October 25, 1950, using surprise and overwhelmingnumerical force, the Chinese struck at the UN forces (led by the Eighth U.S.Army), which was moving up the western region toward the Yalu River. The Chinese particularly targeted the UNright flank along the Taebaek Mountains, whichconsisted of South Korean forces. In theensuing four-day encounter at Onjong (Battle of Onjong), the Chinese severelycrippled the South Korean forces and punched a hole in the UN lines. Thousands of Chinese soldiers then pouredthrough the gap and advanced behind UN lines. On November 1, 1950 at Unsan, the Chinese attacked along three points atthe UN line at its center, inflicting heavy casualties on the American andSouth Korean forces. At this point, the U.S. high command ordered the Eighth U.S. Armyto retreat south of the Chongchon River.

On November 6, 1950, the Chinese forces also broke contactand withdrew north to the mountains. Unknown to UN forces, the Chinese had over-extended their supply lines,which would be a problem that Chinese forces would face constantly during thewar. Furthermore, in this early stage oftheir involvement in the war, the Chinese relied on weapons supplied by the Soviet Union. Later on, the Chinese would also manufacture their own armaments, andreduce their reliance on foreign imports.

The fighting in the north also saw the first air battlesbetween American and Soviet jet planes, leading to many intense dogfightsduring the war. Early on, the newlyreleased, powerful Soviet MiG-15 easily outclassed the U.S. first-generation jet planes,the P-80 Shooting Star and the F9F Panther, and posed a serious threat to theU.S. B-29 bombers. But with the arrivalof the U.S. F-86 Sabre, parity was achieved in the sky in terms of jet fighteraircraft capability on both sides. Ultimately, U.S.planes would continue to hold nearly full control of the sky for the durationof the war.

The sudden Chinese withdrawal during the Battle of Onjongperplexed the U.S.military high command. Weeks earlier,General MacArthur stated his belief that Chinahad some 100,000-125,000 troops north of the YaluRiver, and that if half of this numberwas sent to Korea,his forces easily could meet this threat. In the ensuing lull (November 6–24, 1950), U.S. surveillance planes detectedno significant Chinese military buildup, and sightings of enemy troop strengthon the ground seemed to confirm General MacArthur’s estimates. Convinced that China was not intending tofully intervene in Korea, General Macarthur launched the “Home-by-Christmas”Offensive, a cautious two-sector advance toward the Yalu River: UN forces inthe western sector led by the Eighth U.S. Army as the main attacking force, andin the eastern sector led by the U.S. X Corps to support the attack and alsocut off enemy supply and communication lines.