David Williams's Blog, page 64

November 29, 2015

Christian Storytelling

Over the course of the last month, I've not been blogging. Instead, I've been hammering away on this year's novel. It's part of National Novel Writing Month, which I've done for the last three years, and it's been great. The structures and disciplines and insta-community that springs up around this month-long blast of writing is great. Every year, it's helped me punch down a full draft 50,000+ word manuscript, going from concept to dang-there-it-is in a month.

Over the course of the last month, I've not been blogging. Instead, I've been hammering away on this year's novel. It's part of National Novel Writing Month, which I've done for the last three years, and it's been great. The structures and disciplines and insta-community that springs up around this month-long blast of writing is great. Every year, it's helped me punch down a full draft 50,000+ word manuscript, going from concept to dang-there-it-is in a month.One of the recurring of my writing has been developing stories with Christians woven into them. Being a pastor and all, I suppose that isn't surprising.

My first year's output revolved around the Amish. The Amish after an apocalyptic event, admittedly, so it's a harder and more brutal narrative than your typical pastel romance, but the Amish nonetheless. That one found a publisher, and should be out there...God willing...in eighteen months.

Last year's manuscript included two significant Methodist side characters. Methodists, aliens, and robots. And Russian hit men. Who were not Methodist.

This year, my protagonist is a charismatic evangelical, an evangelical who has an encounter with pandimensional extraterrestrials whose appearance is an homage to H.P. Lovecraft's Elder Things. Because for some reason, those two things go together in my mind.

Besides just pitching out a good yarn, one of my goals in the midst of all of this: to attempt to write stories in which Christians are actual human beings. In my reading and in film, I find that I'll encounter Jesus-people who are cast in only the broadest-brush stereotypes. They're too often Elmer Gantry charlatans or bible-thumping hypocrites or other two-dimensional tropes, and it bugs me. Jesus people are, in my experience, not all like this.

But neither are they the cookie-cutter drones we too often encounter in contemporary "Christian" literature and film, that alternate reality where human complexity gets obliterated by blow-to-the-forehead messaging.

As I prefer to write 'em, Christians make mistakes, and do stupid things, and continue to be genuinely Christian in a world where that's increasingly not the norm.

Which brings me to a point of fuddlement as I've been writing. My Christian characters inhabit a world populated by people who neither think nor speak in particularly Christian ways. Because I'm trying to write in a way that reflects reality, there is profanity. There is violence. And there are Christians, some flawed, some kind, some less so, mixed in to the whole mess.

I do wonder, honestly, how that will work for readers. To what extent can there be faithful Jesus-folk presented in literature that can be horrible or rough or profane? Is that encounter too jarring now, for the Christian reader, trained to expect watered-down and simplified literature? Is that encounter too jarring for the secular reader, who expects easy stereotypes in place of the human complexity that exists among the faithful?

The only way to find that out, I suppose, is to keep writing.

Published on November 29, 2015 11:37

October 26, 2015

Why Your Pastor Should Be a Vampire

Halloween is just around the corner, which means it would be a great time for you to watch a marvelously entertaining recent vampire movie.

Halloween is just around the corner, which means it would be a great time for you to watch a marvelously entertaining recent vampire movie. It's a comedy out of New Zealand entitled What We Do In the Shadows.

It's not technically horror, but a silly, surprisingly endearing comedy about a quartet of vampires living together in a shared house. It's considerably bloodier and with two hundred and seventy five percent more death than most comedies, and I don't commend it for family movie night, but hey. It is entirely worth a watch.

Among the many funny moments was a riff on a classic part of the vampire myth. Unlike zombies, werewolves, and other monstrous critters, vampires can't get you unless you let them. Meaning: they are constitutionally incapable of stepping over the threshold of your home unless you welcome them in. If you say no, or just don't make the offer, they stay out. They must stay out.

That vampire ethic resonated interestingly against one of my core principles as a pastor and follower of Jesus.

Because there are similiarities between myself and vampires. I mean, what do I do? What's my profession? I roam the earth, trying to share the secret of eternal life that I received from the one who turned me. I have an intense relationship with crosses, crucifixes, and holy water. Once a month, I gather with others, and we hold this ceremony where we drink blood.

Admittedly, I neither catch on fire nor sparkle in the sun, but my pasty Celtic flesh does burn in the light of day, so that sort of counts.

The similarity goes deeper, because I share that peculiar vampire ethic about boundaries.

Because it matters to me that your response to faith is authentic, I won't kick down your door to give what I have to you. If you don't invite me in, I'll stay out.

This confuses many Americans, who are used to quite the opposite. The expectation, as of late, is that Christians are the ones who chase after you relentlessly, who come at you and come at you and come at you. They pursue you, overwhelm you, and then eat your brains.

I'm not that kind of Christian. Those folks are the zombie Christians. There are hordes and hordes of them lately, I'll admit. But they are nowhere near as cool, and tend to rot away to nothing in the heat of summer, or freeze solid when winter comes.

I need you to take the step of opening up before I share what I have been given. I will encourage you, call out to you, and make the path as clear and as attractive as I can. But I will not hunt you down, or kick in your door.

I just won't. Because the form of eternal life we Jesus folk offer--one radically grounded in God's love and Christ's compassion--necessarily respects your boundaries, and honors your thresholds. That's how love works.

You have to open up your door, and welcome it in.

Published on October 26, 2015 05:43

October 12, 2015

The Oak, The Reed, and the Multiverse

I spun out a favorite old wisdom story during the children's message a recent Sunday, Aesop's brilliant and pungent little tale about the mighty oak and the humble reed. I'm fond of those ancient fables, beautiful and pagan and wise, and the way they sing in harmony with the wisdom and graces of Biblical teachings. I also like, honestly, that this tradition records--or purports to record--the stories of an owned person. Unlike so many of the faceless, powerless slaves of history, his name remains.

I spun out a favorite old wisdom story during the children's message a recent Sunday, Aesop's brilliant and pungent little tale about the mighty oak and the humble reed. I'm fond of those ancient fables, beautiful and pagan and wise, and the way they sing in harmony with the wisdom and graces of Biblical teachings. I also like, honestly, that this tradition records--or purports to record--the stories of an owned person. Unlike so many of the faceless, powerless slaves of history, his name remains.I also like those stories because, like all narratives, they hang in our memories. As the Teacher knew, nothing clings to our souls like a good story, and the Sunday after I taught it, the kids still remembered.

The story of the oak and the reed is a tale of the illusory character of power, about how those who rely on their own pride and strength do so only until they meet a power greater than theirs.

Even the greatest tree falls before the storm. Better to bend than break.

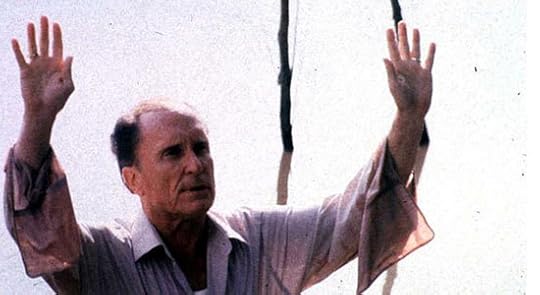

As I wove the tale out for the children, there was a harmony there that rose from the sermon most of them would not hear. The reality parable in the sermon was the life of James Arthur Ray, a quantum-prosperity guru who rode The Oprah to great heights less than ten years ago, and whose hubris destroyed him.

What had struck me so strongly in reading Ray's best-selling book was the degree to which it harmonized with some of my own theology and cosmology. There are parallel universes! Quantum stuff is cool! Engage with your best future selves! Be aware of your co-creative power! Don't abandon discipline and focus!

These are staples of my own thinking about the nature of being, and our place in the cosmos. And here they were, being pitched out by someone who achieved wild success, followed by equally catastrophic failure.

What struck me, throughout the book, was the confidence of it. Ray's confidence in his own power was utter and complete. His confidence in our ability to direct all of the energies of the universe towards our material desires, just as complete. Just buy the book, follow the instructions, and badda boom, badda bing, all the wealth you want thanks to the Law of Attraction or some such quantum hoo-hah.

That confident self-assurance, I suppose, is the difference between he and I. Because if the Creator of a linear, single-narrative spacetime is intimidating, the Creator of an infinitely complex, churning, radiant multiverse is rather more so. My awareness of the multiversality of God's manifold providence only makes me feel very, very much more tiny and mortal.

Having read Aesop's old story, it sounded against that churning vastness, that great roaring deep of Being Itself, suddenly felt like little more than the whirlwind out of which the I AM THAT I AM speaks. Or the storm that roars, against which even the Oak of the mightiest ego cannot stand.

If you stand in encounter with that impossibly vast power, imagining that you in your miniscule way can control it--or you in your ego can withstand it--is absurd.

Better to dance with it, to bend and twirl in the energies around us, than to lie to ourselves about controlling the storm.

Published on October 12, 2015 05:09

October 7, 2015

Buying and Selling American

We recently bought a new van, a replacement for our trusty but rusty old van. It's used, of course.

We recently bought a new van, a replacement for our trusty but rusty old van. It's used, of course.It's a 2012 Honda Odyssey, and I'm proud to own another American car.

What? Honda? An American car?

Sure it is.

The Odyssey is made in America, by American workers. It's right there on the label. Our "new" van was manufactured in the United States of America, in a factory in Alabama. It provides jobs to Americans. Not American CEOs. Not Madison Avenue marketers. But the American workers who build it in the heartland of the United States, and the American folks who truck it from the factory to the showroom, and the American folks who sell it and maintain it.

Not only that, the Odyssey is made from parts that are made in America. At 75% of total parts content domestically sourced, it's as materially American as a Corvette.

But that's not the only thing that makes it American, not in the way that matters to me.

At the height of American greatness, what buying an American product meant was that the transaction supported others who were living as you lived. That car was made by workers who were your peers. You may, in fact, have made it yourself. The wealth of American industry supported the culture from which it came, as egalitarian as the principles that founded the nation.

That is no longer the case. So much "American" product relies on the labor of those who cannot live an American life. They aren't at liberty to pursue happiness, unless by "happiness" you mean endless, hopeless labor. Their fundamental, Creator-given rights have been conveniently, profitably alienated by the new globalized aristocracy.

Products that violate our national principles cannot be considered American.

So in this age of globalization, buying American requires some forethought. General Motors is a global concern. Ford is a global concern. Chrysler is Fiat-Chrysler.

If I buy a Chevy Spark that was manufactured in Korea, is that "buying American?" If I buy a Ford Fiesta that was assembled in Germany, is that "buying American?" If I buy a Jeep Renegade that was designed and built in Italy, is that "buying American?" I don't think so.

Ultimately, buying into that American principle is not just about place.

In buying our Honda, I'm supporting a company that puts money primarily into an excellent product, and into their workers. I am not pouring money into their C-suite.

The CEO of Honda made $1.5 million a year the year our new van was manufactured. That's a lot, a fortune.

The CEO of Fiat-Chrysler in the same year pulled in $16 million. The CEO of Ford, $23.9 million. The CEO of General Motors? A paltry $9 million, which was still six times as much as the Honda exec. And sure, Honda's a smaller company than those global titans.

But it makes a quality product, well designed and executed, and somehow manages to do all of this whilst not feeding the beast of oligarchic/aristocratic CEO culture. What makes for a good product has dang-all to do with CEO salaries. It has to do with competent and honest engineers, a product-first mindset, and fairly paid workers.

Because America at her heart is not, and has never been, about serving the needs of the powerful.

Published on October 07, 2015 07:01

September 30, 2015

The Enemies of the Constitution

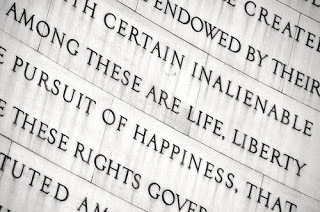

The Constitution of the United States is an interesting document.

The Constitution of the United States is an interesting document.It's not simply that it's the foundation of our system of government, the still-fledgling two-century-and-change republic that we inhabit.

It's that it's really a very functional document. This is not a place one looks for soaring prose about liberty and freedom, though that's in there here and there. Most of the Constitution is as exciting as reading organizational bylaws, because that's what it is. It establishes the structure and framework of our democratic processes.

That, once you've stopped humming the preamble, is exactly what it does. Nothing more, nothing less. It's a rubber-meets-the-road document, one that gets the job done without muss or fuss and hoo-hah, kind of like our just-the-facts-ma'am flag. That's what I like about it, because America at her best is all about just getting it done.

But the simple goodness of that document stands in tension with a peculiar worship that seems to have taken hold among a certain kind of "patriot." The Constitution becomes both Holy and Magic, although it was written intentionally to be neither. It is, as it so pointedly tells us, a document created by human beings for human purposes. It starts out "We The People" for a reason.

That strange idolatry has resulted in an even deeper irony, a cognitive dissonance so deep that it can't be described as anything other than pathological.

The same folks who have turned the Constitution into a totemic fetish distrust anyone who has actually participated in the government the Constitution creates. It is document that is the rule of our national life, that creates the process by which our system of governance works. Meaning, it is the foundation of our political system.

But to participate in our Constitutional system of governance makes you inherently suspect. You're just one of those Washington fat cats, an insider, just another purveyor of politics as usual. The moment of that transition comes the instant you're elected, apparently, which is why having actual experience in Constitutional governance is viewed by so many as a liability.

For those who fetishize the Constitution, it's better to be a talking head. Or, given this political season, an author or celebrity huckster or failed business leader. That view makes souls vulnerable to hearing the voices of those who manipulate and attack the system, the unelectable radical ideologues who'd rather spin out their stories of a bright, cold, faraway imaginary "Constitution" than engage with the reality the authors of the Constitution ordained and established.

Those who treat the Constitution like an idol are, in many ways, the same as the fundamentalists who worship the authority of the Bible. By treating it as something other than a rule for living well together, it makes it far easier to ignore the reality of it, and to subvert the way of life it seeks to shape.

Published on September 30, 2015 05:30

September 24, 2015

Pope Francis and Qualitative Leadership

Having just completed my doctoral work on healthy small churches, I'll occasionally be asked: so, um, what makes a small church healthy?

Having just completed my doctoral work on healthy small churches, I'll occasionally be asked: so, um, what makes a small church healthy?The answer people want to hear is quantitative. They want numbers and data. They want a specific program and pattern that is "replicable" and "scalable." When you think about church like a corporation or institution, that's just how you think.

But a healthy small church is not a quantitative entity. It is fundamentally, frustratingly qualitative. Meaning, it ain't how much you got. It's the character of what you've got. You measure the health of church in the way that you measure the health of families, or of relationships, or of communities.

Or music. Or art. Or a sunset. Or the effect your baby has on you when it first smiles at you.

This cannot be quantified.

Quantitative assessments of those things miss their point completely. No, it's worse than that. They destroy the thing they attempt to assess. They are the wrong tool for the task. Applying empirical measures to the things that give joy is as misguided as brushing your teeth with a claw hammer.

This frustrates those who'd approach church leadership as lightly baptized business management, but honey, it's all about the quality. The health, strength, and purpose of any church rests in quality, which is notoriously hard to quantify.

Wait, you say. Big churches are institutions, with complex structures. Maybe in your little Jesus tribe of a church, qualitative measures matter. But Large needs Quantitative. Leaders of the large must focus on their organizational dashboards! They must have metrics! They must manage!

To which, I would say, look at Pope Francis.

Pope Francis is fascinating. Here in DC, it's like the Fab Four showed up in town, a Pope being received as a celebrity. But not just a celebrity. A Holy Man, someone of unblemished goodness, a beneficent soul, the Papa Di Tutti Papas. That's the buzz, anyway.

But what makes Francis so wildly intriguing to me is that he's really no different from Benedict.

Honestly, he's not, not quantitatively. I followed Benedict closely during his tenure, and he said exactly what Francis has said about capitalism, science, and the environment. Benedict talked in the same way about abuses within the church, and acted to oppose them. I did not always agree with him, but I had a profound respect for his intent, his intelligence, a respect that was deepened when he had the wisdom to step down once he knew he was compromised.

Francis and Benedict, in terms of policy and theology, were remarkably similar. There is almost no difference. Quantitatively, that is.

The difference is tonal and qualitative. Francis understands, instinctively, what faith leadership is all about. It's about manifesting a particular value into the world, in your person. It's about the care of little details--not management details, but interpersonal details. The feeling of a relationship. The timbre of a voice. The twinkle of an eye. A genuine laugh, or a long hug. Loving others, in a way they can feel. Those things are hard to teach. They are not the stuff of tests and metrics. They're the stuff of soul work and personal transformation.

These things matter in the small church. They are its life and breath.

But they are also the heart of every church, at every size. Look at the impact Francis has had on his little church, if you doubt me.

The Way we walk is qualitative.

When the leaders of the church forget this, the heart of the church dies.

Published on September 24, 2015 05:23

September 23, 2015

The Rise of Sharia Law in America

On the American right these days, there's a great deal of talk about "sharia law," the legal code of Islam.

On the American right these days, there's a great deal of talk about "sharia law," the legal code of Islam.There's fulminating about the insidious power of religious law, taking over the country.

The truth goes deeper. Because there are communities of immigrants who have been living under religious law for centuries, right here in America.

I can tell you, from direct personal experience, that these systems of religious law came here with immigrants and have burrowed in, right here in America, working their subtle subversions. These cells of religious zealots from a barbarous, violent land have chosen not to use the legal system enshrined in our national and state constitutions to settle their disputes.

Instead, they have their own arcane laws, rooted in the strange ways of their peculiar faith. They mete out their own punishments, none of which have anything to do with the Constitution of the United States of America, or with state or local laws. They convene their own courts, which pass judgment and inflict sentences on others. Those courts are answerable to no-one but these zealots, a law unto themselves.

Who are these subversives, who defy the Constitution with their perverse theocratic system of "laws?"

You know who they are, and so do I.

I am speaking, of course, of Presbyterians.

I live under such a system. We Presbyterians have our own laws, and our own courts, our own approach to due process, and our own penal code.

It's in a section of our Constitution called the Rules of Discipline, and we use it to settle disputes and issues within our churches.

It's actually kind of a scriptural mandate, if you read your Bible. Christians shouldn't sue one another, or use the court system to handle disputes. You do that internally, working it out among one another.

And so we do. Or should. The siren song of lawyering up is hard to escape sometimes.

In that, we're no different from our Methodist or Episcopalian brethren and sistren. We're no different from nondenominational sorts, who discipline their members, or from Latter Day Saints, or from Orthodox Jews, or any other of the flavors of American religion.

That's been a part of religious life in America since there was religious life in America.

Of course, those courts have only what power you allow them to have over you. You are free, at any point in the process, to say, "You have no power over me." And with that, the spell is broken.

No one gets executed or imprisoned for violating church law. No-one gets flogged or locked into stocks in the public square. There was a time when Christian courts did this. That's why people came to America--to get away from that mess.

It's why, frankly, so many Muslims are coming to America. First Amendment freedoms are what makes this country worth coming to.

We know this. And yet, as Muslims move to America seeking the freedom to practice their faith without fear, the existence of "sharia" courts has become an implement in the hands of the fear-mongering reactionary right wing. "Look at these Muslims, bringing their sharia courts to America! Sharia law! Unamerican!"

But here, that looks different. You can have a court. You can adjudicate disputes. But the only power you have is the power that all parties freely give. No one gets stoned to death. No one gets beaten. Muslims, here, are doing no more and no less than Christians and Jews do here.

As is their Constitutional right.

There is no reason -- no sane, authentically American reason -- to feel even faintly threatened by this.

Published on September 23, 2015 04:06

September 21, 2015

Faith, Privilege, and Power

Privilege is such a peculiar concept.

Privilege is such a peculiar concept.It's the buzzword of the day, the mantra of the earnest, well-meaning left, and on many levels, I get it. But on others, well, the concept seems peculiar. There's an exercise out there now called the Privilege Walk, in which participants are encouraged to take steps forward or back based on a set of criteria. Are you white? Step forward. Did your parents divorce? Step back. Are you college educated? Step forward. Have you ever not been able to afford medical care? Step back. The goal: "illuminate privilege."

What "privilege" entails varies depending on the version of the exercise. Some versions are oriented towards gender/queer issues. Others focus on race. Usually, there's a filter of socioeconomic status. In almost all of the versions I've encountered, I am at or close to the front.

This is not surprising. I am, "white," male, straight, raised by two loving parents, educated, the upper end of middle class, all those things. What I wonder, looking at that exercise, is just what organizers figure will happen next. I mean, seriously, don't we know this already? Race is a toxic proxy for class in our corporate/aristocratic "ownership" culture.

After such an exercise, there will be discussions, sure, and people will feel resentful and helpless or guilty and helpless. And there will be more discussions, and participants will feel more divided and less unified. But will those conversations do anything, other than heighten anxiety?

No. No they won't. Heightening anxiety is their primary purpose. They are deconstructive, in the matter of all academe. There can be a place for that, but it's limited. If all you know how to do is tear down, you will never build anything.

"Check your privilege," or so the saying goes, and in some ways it's helpful. I don't get pulled over for driving while black, for example. I don't fear for my safety while walking at night. I don't get harassed because I look sorta generically Middle Eastern. I don't worry about financial ruin if I get sick. If I did not recognize that my reality is not the norm for others, I'd be a fool.

But in mindlessly applying that principle to everything, "progressives" sabotage progress.

The issue with being "privileged" is that an unbalanced culture gives rights to some, and denies them to others. If I can interact with law enforcement officers with confidence, speak and move without fear, then that isn't something I need to "check." It's something I need to share, in the way that knowledge must be shared. I need to press for justice for those who are denied those same, inalienable rights.

And while the imbalances of unjust privileging are worth fighting, privilege itself is something misused by deconstruction. Privilege is the absence of oppression, and in that it is power. As power, it can be used used rightly in a culture. Privilege can bring about change.

If privilege has given you the right to speak without fear, and the right to be heard, and the ability to stand against oppression unchallenged, then that is to be used.

Within the aeons of sacred story rising from my faith, there are examples of those who used privilege rightly.

There's Isaiah, the poet-prophet whose tradition sings furious against the imbalance of economic power and worldly privilege. But Isaiah himself was a man in a position of power. He moved among the Jerusalem elite. He had the ear and the respect of kings. He was, as they say, privileged... meaning he could speak truth without fear and be heard by power.

From his position, he challenged the economic imbalances of urbanization, and the power imbalances that served the privileged elite.

And sure, he could have checked himself, but the call for justice would have been lessened without his voice.

Or Paul, Paul the educated, rhetorically gifted, classically trained apostle. Paul--not his culturally conformed disciples, but the soul that gave us the Seven Letters--spread Christ's message of a radically egalitarian form of being, which fundamentally subverted the power dynamics of Greco-Roman society. And yet when that power came for him, he didn't recoil from his identity as a Roman citizen. He used it to face down power, to push back against power with its own strength.

"Do you realize I'm a full Roman citizen," he'd say, and those who'd imprisoned or beaten him would blanch.

He knew he was a bearer of privilege, and knew how to use it to sabotage privilege itself.

And in those ancient witnesses, a truth: privilege is power, power to act, power to make change. Reflexively attacking every manifestation of power only impedes transformation.

If you find yourself with power, and you do not use it for good but instead spend all your energies deconstructing it, how does that serve the cause of justice?

Published on September 21, 2015 05:51

September 19, 2015

Impermanence Imbued with Presence

Early in the morning, as the day was dawning, the flatbed showed up and took away our van.

Early in the morning, as the day was dawning, the flatbed showed up and took away our van.It was a good old van, a white 2002 Honda Odyssey, bought very lightly used thirteen years ago. Nothing fancy. Nothing special. Just a thing.

There is nothing more practical and perfect than a van.

And after all that time, it still ran like a top. Sure, a few dings here and there, and the rust spots and scrapes of a decade. But as we watched it driving gamely up onto the back of the flatbed, donated to a wonderful charity that gives reliable vehicles to families that need transportation, we knew it'd serve another family well.

We'd replaced it, because we've been blessed enough to be able to get another van. Used, again, of course.

Letting it go was interesting, because though it's just an object, and a relatively generic one at that, it's imbued with memories.

For a quarter of my ever lengthening life, it was present. It was the van that shuttled kids back and forth to an endless stream events, that took us on long road-trip vacations. To the beach. To the lake. To ski. Across state and national borders.

My older son sat in his car seat as we listened to Bert and Ernie sing. A decade and change later, it was the vehicle in which he learned to drive.

I sat with the boys in the back, doubly sheltered by the hatch and the carport, as we watched the trees shake and rock while Hurricane Isabel blasted through.

Seats lowered and removed, it has carried mulch and bricks and dryers, or the futons of friends on the move. Seats up, it has been filled with children and grandparents, or packed with an entire birthday party full of 13 year old boys on their way to ice cream and laser tag.

It drove back and forth to schools, and to concerts, and to swim meets, and to drum lessons, for hours upon hours, days upon days, the equivalent of four times around the planet. Assuming an average of 35 miles an hour, we spent an average of one hundred and twenty one entire days in that van.

It's given so many memories, yet is is not a place or a home but close, a capsule in which the souls that make a place home moved and journeyed.

And now, it's gone, as the things we suffuse with our presence do go.

Published on September 19, 2015 05:01

September 16, 2015

If It All Came Out Even

An unused remnant from my sermon research a couple of weeks ago stuck around in my head, a peculiar datapoint about faith, wealth and poverty.

An unused remnant from my sermon research a couple of weeks ago stuck around in my head, a peculiar datapoint about faith, wealth and poverty.It came out of my challenging an assumption I've had for a while about globalization. My assumption, rather simply, had been this: the process of globalizing our economy means that the economies of formerly industrialized nations like the United States are slowly "leaking" into the broader world economy.

Meaning, in fifty years, there will be no difference between the average American and the average Indian. Or the average Mexican. Everywhere, the rich will be just as rich. The global elite look pretty much the same, wherever you find them. But the average person will have...well...what?

I looked around for the primary datapoint relevant to a globalized economy: the Global World Product. How big is the planetary economy, when you fold in everything humans do everywhere?

It's not something that's regularly out there as part of conversation, as we still--stupidly--think in terms of nation-states and localized economies.

I found the data on Wikipedia, of course. $87 trillion in US dollars as of the last year it was calculated, or so the impossibly vast numbers run.

As that's currently divided up, with the lion's share going to the rich, we know what it looks like. But what if it was all divvied up equally?

I assumed that we'd all be barely above the poverty line. From the grasping anxiety of my privileged position, I assumed it would be a disaster, because really, when you get down to it, surely there's not enough to go around.

What surprised me was that there is.

If we divided the Global World Product up even-steven, everyone getting exactly the same share, in 2014 my datasource tells me it would have come out to $16,100 United States dollars per human being. That's sixteen thousand one hundred dollars per soul, $16k for every man, woman, and child on the planet.

Hey, you say. I don't like the sound of that. That information probably was fed into wikipedia from some commie leftist. Bernie Sanders, most likely.

It's from the United States Central Intelligence Agency's World Factbook. Buncha pinkos.

Huh, I thought. Because looking at my household, the four of us could live on that. Sixty four thousand, four hundred bucks? It's way less than we make now, but we'd get by. Totally. No problem. Not so many years back, we had two kids, two nonprofit jobs, and made less than that as a family.

It'd get hard, as the boys grew up and moved on, but we'd figure out a way. Life would go on. We'd learn to work together, and how to pool our resources. We'd neither freeze to death in winter nor starve.

For the average American, it'd be a hit. At 2.58 persons per household on average, that yields an average household income of $41,538, about a 20 percent hit from our current average household average of $51,939. Honestly? Dude, that's completely doable. Here in the DC area, where your debt dollars have fueled a huge surge in the cost of living, that might seem untenable. But average folks in Alabama seem to manage it.

Because then I thought of the billions who do starve, the billions who struggle in backbreaking labor in dry, grudging fields. I thought of those who work insane hours in the globalized factory floors of Asia, doing the work that used to provide for middle class American incomes for a tiny fraction of the wage.

For a Sudanese, what would $16,100 a year mean, if it was everyone in their household? It'd be ten times the average. For a Bangladeshi? Fifteen times the average. For the average Chinese worker? Four times as much. It'd make the difference, night and day.

In the event the robots took over and imposed such a system, we'd pitch a major hissy. It wouldn't be fair, of course. What about the lazy goodfernuthin's who don't deserve it? What about the vaunted creatives and producers? Don't they deserve so very much more? In the metric of our worldly economy, sure. That's how they run this planet.

But I wonder if our resistance has to do with "fairness." Does it reflect our real needs? Or is it a factor of our jealous hungers, and the wild imbalance of our system?

And I was reminded of Jesus, asking us to pray for our daily bread, for only what we really need. No, what we REALLY need. Not our wants. Not what we're used to, or have been taught to expect.

And I was reminded of Jesus, and that crazy commie story about laborers in the vineyard, the one he told about how in the Kingdom we're all the same.

Because the Kingdom economy and the economy of the flesh are very, very different things.

Published on September 16, 2015 05:19