David Williams's Blog, page 68

June 24, 2015

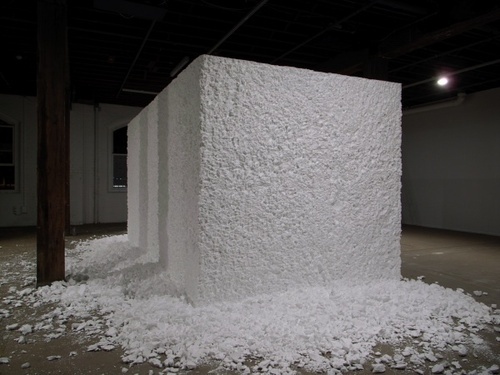

Deconstructing Whiteness

"White" is such a strange category, such a peculiar label.

"White" is such a strange category, such a peculiar label.Oh, I know I am supposed to fit that category, according to the perverse metric of modern-era racial categorization. But I'm not attached to it, not in any way. Some folks will say that this is my privilege talking, that I can feel unattached to "whiteness." It's their right to think that, but honestly, I don't feel that connection. In fact, to effectively dismantle white privilege, it's necessary to realize that "whiteness" does not need to be an integral part of a person. That when "white privilege" is challenged, it's not an attack on a defining characteristic of a person, or on their identity. It is an attack on a Power, as my faith tradition would put it.

Because the idea that there is a "white" race or ethnicity is as absurd and irrational as the misbegotten idea that there was an "Aryan" race. It is a fabrication. It isn't just that there's no scientific basis for such an identity. Socioculturally, "white" is incoherent. Are the Irish English? Is a German French, or a Ukrainian a Russian? No, of course not, any more than a Persian is an Arab, or a Hausa a Yoruba, or Hutu a Tutsi, or than a Korean is Japanese.

Ethnicity assumes a common set of values, shared stories and language and myth. And where I connect with the history of my complex and muddy blood, it is there. I recall my Scots/Dane ancestors, with their castles and crags and raven-flagged galleys. I recall the travels of my itinerant Irish day-laborer ancestors, and the indentured English servants who were brought over as owned people. Those parts of my mongrel heritage have specific content and place and story. They are not perfect, as no culture's history is perfect, but I can hold them and honor them. They are legitimately part of my self-understanding.

But "white?" I have no "white" heritage that I allow to be an integrating influence, or in which I can take pride. I feel "Whiteness" as an oppressive other, part of a demonic binary that would claim me. "Whiteness" clings to my face like a suffocating shroud.

Oh, there is "white" history there, no doubt, from back when the delusion of racial dualism cast a pall over centuries of human history. I know, for example, that there were Klansmen on the Southern branches of my family tree. They had a sense of their "whiteness," and I remember that aspect of their identity. But though I remember, it is remembering as lament, not embrace.

It is the kind of remembering that says, this was a grim chapter in our story, one we recall not with pride, but so it will not be repeated.

"White" is the lie of the pure racial binary, the lie that says that there are "whites" and "coloreds," or "whites" and "people of color," as if a person cannot celebrate both their Scots and Kenyan heritage, or be of Chinese and German roots, or fully embrace both Afro-Caribbean and French cultures. It is the falseness of establishing simple dualistic boundaries on the complex continuum of human cultural identity.

I am perfectly willing to see the way that the label of "whiteness" confers unjust advantage in our culture, and the ways I unwillingly benefit from that injustice. But "white" confers none of the narrative that I use to construct my identity, and the assumption that it does--that it must--is part of the great binary lie of race that has corrupted the American story.

Published on June 24, 2015 06:47

June 17, 2015

Biblical Truths and Context

The Bible, or so some folks who think they've discovered something profound will tell you, disagrees with itself. "Your holy book doesn't add up," they say.

The Bible, or so some folks who think they've discovered something profound will tell you, disagrees with itself. "Your holy book doesn't add up," they say.Not being a bibliolatrous sort, I've never been particularly phased by that argument. Incongruities? Inconsistencies? Differences of opinion? In an ancient compilation of sacred books that spans multiple cultures and aeons of human history?

What a surprise. I'm so shocked. My faith is shaken to its core.

But as I prepared for this Sunday's sermon today, I encountered one of the most striking disagreements in all of Scripture.

It's found in the book of Proverbs, that collection of wisdom poems, sayings and aphorisms. Ancient though it may be, its teachings about integrity, covenant fidelity, prudence, and diligence are still entirely applicable to the human condition. We're not nearly as different from the ancients as we might like to think.

In the twenty sixth chapter, verse four, we hear the following bit of advice:

"Do not answer fools according to their folly, or you will be a fool yourself."

Which is, of course, completely true. If we listened to that wise advice in this era, we'd never ever ever again respond to a trollish comment on social media, or take umbrage at some bit of impossible idiocy we encounter in a blog. Such net wisdom, from twenty-five-hundred years ago, back when all they had was MySpace.

Then, in the twenty sixth chapter, verse five--the very next verse--we hear the following:

"Answer fools according to their folly, or they will be wise in their own eyes."

Which is, of course, also completely true. When you see someone who is totally sure about something utterly wrong, you're well within your rights to go all Snopesy on them. "Vaccines cause autism! The moon landing was a conspiracy! Printing money is a great way to grow an economy! Donald Trump is a viable presidential candidate!"

Bringing reason to bear on those misbegotten things is a way of countering the spread of such foolishness.

But these two verses give diametrically opposed advice. "Do not do Thing A!" "Do Thing A!" "Answer fools!" "Do not answer fools." Thesis and antithesis, right there, next to each other.

Sure, Proverbs is disagreeing with itself. But the ancients who compiled it were doing so on purpose, in a way that you couldn't miss if you tried. They were doing so to make a point.

That point, made from the Bible: Truth is truth, but it is also contextual. What is wise and right and good in one circumstance can be utterly misapplied in another. Because even if you give a fool a truth, they'll not know what to do with it. They'll wave it around, brandishing it wildly, and in doing so will harm both others and the truth itself.

It is a peculiarity of our foolish era that we seem to have forgotten that.

Published on June 17, 2015 12:06

June 15, 2015

The Practical Motorcycle

No-one wanted it. No-one. It sat, unwanted, for a year and then another.

No-one wanted it. No-one. It sat, unwanted, for a year and then another.The reasons were many.

It was designed to be a practical motorcycle, and really, who wants a practical motorcycle in America?

A motorcycle that is described in reviews as "comfortable" and "respectable" and "nonthreatening?" A "good buy for the value customer?" That comes in a color that was intended to be the Rommel-esque "Desert Khaki," but that could be just as easily described as "tan" or "beige," the color of your grandparent's '69 Dodge Dart?

This will not appeal to the young and testosterone-addled, or the receding-hairline mid-life crowd. We want our rumbly Hogs or our screaming crotch-rockets, the "lifestyle choices," bolsters to our market-anxious egos, a sign that we are loners and rebels and born to be wild for payments of $249 a month.

Oh, sure, it was fast. The one thousand thirty seven cubic centimeter engine that throbs under the tank was derived from the legendary TL1000S "Widowmaker," notorious from a decade ago. It was a motor whose power so overwhelmed its chassis that even the most experienced riders would be thrown high-side like drunkards from a mechanical bull. But designers corralled those wild horses and that snorting torque with an excellent chassis and suspension, antilock and traction control. It is swift, but not wicked.

It was also not expensive, not ever, and from a brand that bears no aspirational provenance. It's not a marker of wealth and success, a way to peacock your prowess to the world.

It was quiet, in the sort of way that if you fire it up on a Sunday morning to go to church, the neighbors won't even notice. That great big stock muffler means no babies will be woken. It's just so very civilized. Polite, even, like Brando after a particularly productive anger management class.

And it was a little ugly, a peculiar beaked goony-bird of a bike, looking for all the world like one of the Skeksis from Jim Henson's The Dark Crystal.

So there it sat, swift and comfortable, perfectly capable of doing just about anything one could ever want. Commuting? It's just perfect. Riding to California tomorrow with your wife on back just because? Absolutely, if you inhabit the alternate universe in which she's up for that. Light-duty off-roading? It'll do that. Embarrassing Corvettes and Mustangs? Sure, if you're in that sort of mood. It is a motorcycle made for riding.

But still, no one wanted it, as the price was slashed again and again and again. There it lay among the shinier bikes, like sweet little Corduroy on the shelf, overlooked and sad and missing a button.

Which is why I just had to bring it home, because...having counted what I saved in my piggy bank...I knew it was exactly the bike I've wanted.

Published on June 15, 2015 06:37

June 12, 2015

Collateral Beauty

I'd never planned on growing flowers.

I'd never planned on growing flowers.Oh, I think flower gardens are a lovely way to spend one's time. They add a little beauty to our world, and make for a wonderful visiting place for our beleaguered pollinators. I can see the delight in that.

But that's not my goal, as I plant. My garden, insofar as I put time into it, is all about the delight of producing even a fractional amount of our household food. My enjoyment comes from the taste and flavor of those things that rise from the earth, from the beans and strawberries and blueberries, from the tomatoes and potatoes and squash. That I am in some small way nourishing my body with those simple labors has a nourishing effect on my soul.

So I did not set out to have flowers, to have beauty for the sake of beauty, though I appreciate it.

But of course, I do have flowers. You have to, if there is to be fruit. There are so many.

I'd expected the little white strawberry flowers that dappled our patches, and the tiny, delicate ivory blossoms on the bush beans.

I knew, in the back of my mind, that tomatoes came from little yellow caps, that dangle down from their vines like the headgear of some anime elf-maiden.

But I did not anticipate the lovely white and purple of the potatoes. And newbie that I am, I had no idea that squash would be such a riot of immense, yellow-orange trumpets, male and female both.

So there's my garden, turned to the simple, unassuming labor of producing good things. And in the midst of that labor, almost as an afterthought, it is filled with splashes of color and loveliness.

There are lives like that, too, human beings who are intent on giving and producing simple goodness. And even though they aren't intentionally setting out to be beautiful, they are.

Published on June 12, 2015 14:01

June 9, 2015

Good Fruit and Expectations

"You shall know them by their fruit."

It's a pretty straightforward teaching from Jesus, laying out for us how we can tell the difference between folks who really teach and live out the Way of grace and folks who are just in it for power. What are the results of an individual's life? How do they shape the world around them?

And from our home gardens, and the plots in the Community Garden, we have a sense of that. Berries and fruit trees, or the vegetables that now begin to fill our summer tables, all of these things give us a sense of what makes for "good fruit." Here it is, right on the plant, and either it grows or it doesn't. Either it tastes good or it doesn't.

This year, I decided to do something a little bit different in my front yard. To the beans and berries and tomatoes and squash, I added in a half-barrel filled with dirt and compost. The goal: potatoes.

Hailing from Scots-Irish ancestry, I think there's something in my genetic makeup that's particularly fond of potatoes. They're just good, hearty, flexible, energy-yielding yum-ness. You can bake them with a sprinkling of garlic, salt, and olive oil. You can fry them. You can boil 'em, mash 'em, stick 'em in a stew.

As I learned when doing my pre-planting research, potato plants are interesting critters for another reason. They will produce fruit. Not always, but when the conditions are just right, those pretty little clusters of flowers on the top of the plant will become fruit that looks almost exactly like a tiny little green tomato.

Cut it open, and it's filled with little seeds, just like a tomato. Eat it, though, and things get a little unpleasant. Potatoes are the close cousins of deadly nightshade, and both their fruit and their leaves are poisonous. The poison is particularly concentrated in the fruit, causing headaches, convulsions, intestinal distress, hallucinations, and death.

And so, as the potato plants grow up like gangbusters, their tubers still hidden under the earth, I find myself reflecting on good fruit and our expectations of others.

If you found yourself stranded on an island where wild potatoes grew, you might see the fruit and think, hey, maybe I can eat that. But after you munched down the fruit, by the end of the next day you'd be pretty darned sure you knew the answer to that question.

Stay away from those plants, you'd say to yourself, groaning. They're poisonous and horrible.

But that's just because you'd only be looking at the surface, and seeing the thing that *seemed* to be the edible part of the plant. You'd be making a judgment about what was and was not good based on a partial understanding.

And you'd go a little hungrier for it.

We make the same mistakes with other human beings, I think. We have, in our minds, a set image of what it means to be good. So when we encounter persons whose "fruits" do not meet our expectations, we may choose to label them negatively before considering the fullness of what they have to offer. We don't give ourselves time to discover the ways in which they may be good, quickly dismissing them as unworthy or our time and attention.

Jesus certainly didn't do that, not with tax collectors or adulterers, not with the outcasts or the unclean or the traditional enemies of his people. He sought the goodness and saw the potential in all, and challenged us to do the same.

So as I tend my garden plots this summer, I take those moments to think about what is and is not fruit, and remember to consider the wholeness of every person I encounter.

Published on June 09, 2015 09:56

June 4, 2015

The Christian Salesman

It'd been a marker of sorts, part of my identity for the last four years and change. My bright yellow motorcycle, a 2008 Suzuki VStrom 650, had gotten me to and from church. It'd picked kids up from school, and taken them to events, and generally been a trusty companion as I negotiated the steel and asphalt blender of Beltway traffic. It's carried me twenty six thousand miles over the last four years, three times around the diameter of our little planet.

It'd been a marker of sorts, part of my identity for the last four years and change. My bright yellow motorcycle, a 2008 Suzuki VStrom 650, had gotten me to and from church. It'd picked kids up from school, and taken them to events, and generally been a trusty companion as I negotiated the steel and asphalt blender of Beltway traffic. It's carried me twenty six thousand miles over the last four years, three times around the diameter of our little planet.At my church, I've been the "pastor with the motorcycle," which both carries coolness cache and helps introvert-me open conversations.

Last night, I sold it.

I'd been thinking of selling it for a while, but events conspired to make this the right time to let the ol' girl go, and so up onto Craigslist I went.

And there, as I approached that sale, I encountered a conundrum. A moral dilemma in miniature, one that played against my understanding of ethics, free-will, human agency, and the nature of our place in creation and the interconnectedness of all things.

All this, in a simple transaction. We Presbyterians do overthinking better than anyone else on the planet. Seriously.

Anyhoo, the dilemma was this: I wanted to sell my motorcycle. And I wished, from the income of that sale, to purchase another. That process could have countless variant outcomes, which would be shaped by the ethic I bring into the exchange.

I know, for example, that my bike presented well. It was bright, gave the appearance of being well maintained, and was desirable. It started up immediately, and ran like a top. VStroms have an excellent reputation. It would not be a hard sell.

But I also know that the bike had developed an electrical gremlin, one that only surfaces after it has been run for an hour. It's stranded me repeatedly over the last month, which was my primary motivation for the sale.

The issue is possibly a slowly fading alternator, but could be something else. It'd been gone over by mechanics I trust, and hundreds and hundreds of dollars spent, but remained unreliable. There would be no way for a buyer to determine this during a test-ride, or without running the bike for more than thirty minutes.

And so the question became: how to proceed? There were so many ways to move forward. If profit maximization was my goal, I would simply choose not to disclose. When asked how it runs, I would equivocate carefully, using language to dance around any questions. "Why are you selling it?" "Oh, I want a new bike," I would say. "Any problems?" "It starts and runs great," I would say. At no point would I lie. I would just limit the truths I chose to share.

I could craft an ad that is designed to entice an eager and unwise buyer. Speed! Power! Adventure! Fun! Once the title was signed over, and a bill of sale indemnifying me from any liability or responsibility was co-signed, I would be legally free and clear. Caveat emptor, as they say.

This is the outcome from which I would profit most maximally, the Ayn Rand, Milton Friedman outcome. I have no relationship with the buyer to jeopardize, and there is little they could do to impact my broader reputation. I could create that reality with no difficulty.

But I know what it's like to be stranded by the side of the road, and the feeling when others have taken advantage. From my Teacher, I have an ethical framework that recognizes my essential connectedness to all things, and that assumes that I am radically culpable for my intentionality and actions towards others. And so, even here in this mundane situation, my theology is at play. If faith does not inform every last part of one's being, after all, it is not faith.

I want to sell, but at a price that is fair. I do not wish to inflict, in the process of that sale, any harm, or in any way take advantage.

Further, I want to avoid doing collateral harm to an eager fool, some young idiot like I used to be, ready to rush in and buy, all filled with passion and without a lick of sense. Oh, they're sure it'll not be a problem for them, because wow, OMG, a motorcycle! And how hard can learning about all those wires and [stuff] be?

That results in the world becoming a little more cynical, and in my well-loved bike sitting out in the rain at someone's parent's house, slowly rusting and unused. It would be a waste of a good thing, and the world would be made slightly worse by that choosing.

I did not wish that reality to be made manifest.

So I set the price in recognition of the issues and factoring in the likely cost for repair. That, by my conservative calculations, was around half the value of the bike had it had no hidden issues. Then I wrote the ad carefully. It was written with intent, filled with keywords that indicated that I was both aware of the value of the bike and fully disclosing all issues. I explained pricing, which I set firmly because I hate haggling. I structured the phrasing to bring in a serious, aware buyer who both appreciated the potential but saw what would be required.

And so, when my buyer arrived, he was a lifelong motorcyclist and tinkerer, who works in an Army electronics research lab. He asked all the right questions. Then he checked it, doing the sort of thorough walk around that indicates seriousness. There was no haggling, or negotiation. He knew it was an excellent price, more than fair, and a great bargain and opportunity for someone with his skillset.

As I rode off, I wished him well, and gave thanks that what I had hoped for had come to pass.

Published on June 04, 2015 05:50

June 2, 2015

Faith, Brand, and Identity

What is it that defines us, as beings? What gives cohesion to our sense of ourselves, and from that establishes our relationship to others?

What is it that defines us, as beings? What gives cohesion to our sense of ourselves, and from that establishes our relationship to others?These questions were bopping around in my head the other day while walking the dog, hovering about like the summer gnats that flew around me in a cloud.

Two ways of understanding identity surfaced and played off of one another. On the one hand, identity as "brand." On the other, faith.

Brand identity is the Big Buzzy Thing in our consumer culture. It used to be less all pervasive, less radically defining. I mean, shoot, back when I was a kid there was Tide and Ivory, Coke and Pepsi, Chevy and Ford, but those lived in their own domain. Now, with the net-driven commodification of all human interaction, we're all supposed to attend to our brand.

But what is this identity, that brand-focus creates within us? Brand is about the relationship between a product/service and a consumer of said product/service. It is intended to develop a pattern of repeat or customary purchase, based on the consumer's perception of qualitative dynamics of the brand.

I use Google products, for instance, like this blog platform, and Gmail, and my Chromebook. I use them because Google represents, for me, innovation coupled with an imperfect but intentional beneficence. I eat at Chipotle, because, again, there's a general focus on doing less harm, plus it's dang tasty and a heck of an option for non-carnivores like myself.

Brand does more than confer corporate identity. It "rubs off," by intent, in the relation. The brands we consume are meant to modify our own sense of self, to be a social marker within culture as to our place and status.

I'm composing this on an iMac, which bears the Apple brand, as does my iPhone. That is meant to tell me that I have disposable income, that I am successful, and that...from the suite of creativity software bundled with the iMac, that I am part of the self-styled "creative class." This is a good thing, because those folks are the only people still allowed to make a living in our culture.

Out in the carport and driveway, we have a Honda and a Toyota, which tell us that we are a practical, reliable, comfortably bourgeois family. The more we internalize the brands we interact with as shaping our own identity, the more we are embedded as a consistent and reliable consumer.

And so the question becomes: what is the relationship between brand identity and an identity shaped by faith?

It's an important question, because as branding becomes the defining feature of both corporate and individual self-understanding, there's bleed over into the realm of faith. Churches need to "think about their brand" in the process of the endless self-promotion we're now obligated to pursue. Our living out of spirituality together becomes both shaped and expressed in terms of the market ethic. Is that an issue?

Honestly, it is. Because faith shapes identity in ways that are radically different from "brand."

Brand, after all, is about ownership and possession. It is driven by commodified self-interest. The point and purpose of branding is to promote the corporate or individual person being branded. While it creates relationship, that relationship is essentially grasping, oriented to benefit the brand itself.

And in that, brand identity is the inverse of the identity created by faith.

Faith is oriented not towards the self, but the self orienting itself towards a purpose that transcends self. Or the organization orienting itself towards a purpose that transcends organization. The telos created by faith--or at least, an existentially valid faith--challenges persons to be grounded in something that will continually demand their own growth. It is relation with the other rooted in the other.

An identity shaped by faith is a different thing, a different thing entirely, and that's worth keeping in mind before we press that hot metal against the surface of our souls.

Published on June 02, 2015 10:09

June 1, 2015

Explaining the Trinity

Yesterday was Trinity Sunday, that Sunday when pastors hem and haw and preach on something else. I was crankin' up the start of a sermon series, and so I didn't go there. Not yesterday.

Yesterday was Trinity Sunday, that Sunday when pastors hem and haw and preach on something else. I was crankin' up the start of a sermon series, and so I didn't go there. Not yesterday.But that doesn't mean I'm shy about the Trinity, or that I hem and haw around it.

Like the Sunday before, when I'd found myself at a Jewish retreat center, celebrating Shavuot with that community. I and another area pastor had been invited out by their rabbi to talk about Pentecost, and the way we Jesus-followers understand this festival day that our traditions share.

My colleague hit most of the theological points I was going to make, so when I got up to talk, it was mostly about the connections I have with the Jewish community personally, having married into the faith and raised two Jewish boys.

Afterwards, I stuck around, and engaged with folks, and in the manner of any good Jewish conversation, there wasn't a whole bunch of shyness when it came to getting right to the hard questions. One woman, a sharp-minded Israeli who'd already pitched out some incisive, well-stated hardballs, got right to it: "Explain the Trinity to me," she said. "It has never made any sense to me at all."

Righty-o.

And so I did, launching into my usual wide-open-throttle explication of the philosophical underpinnings of trinitarian thought. I started with Tertullian, because that's where it begins, and we reformed types have to go ad fons in any explanation.

From there, I explored Tertullian's use of the term prosopon, or "persona," to articulate the interrelation in his treatise Adversus Praxean, and how prosopon means a corporate person in Roman legal thought and is also the name for the identity-masks in classical Greek drama. Then, on to the Cappadocian Fathers, and the deeper application of Aristotelian substantial frameworks implicit in Tertullian to the nature of the relationship. Then, to more explication of the idea of substance to articulate ineffable, fundamental identity, and its use to posit union even in the presence of categorical frameworks that allow the creation of distinctions.

Yeah, I know, slow down, son. But she asked, it was clear she wanted a serious answer, and she was following.

But showing that the Trinity was a thoughtful, culturally-relevant, and spirit-grounded effort to make the three-and-one implicit in the Gospels and Epistles coherent in a Greco-Roman philosophical context is one thing. It is another to express how that form of categorical thinking has purchase in monotheism.

And so from there, I rolled straight into Kabbalistic and Talmudic understandings of G-d. Because, sure, Judaism is completely monotheistic. But our mother-tradition has been around the block with the Tetragrammaton enough to know that the Creator of the Universe can be understood in many ways.

"Think of it as similar to the divine emanations of your mystic tradition," I suggested. "For we Christians, our encounter the Divine is in three expressions, which are distinct in manifestation and conceptually different, and yet at the same time completely one."

"Or like the shekhinah, the divine feminine," she said, and I could see in her eyes that the connection had been made. The Trinity suddenly made sense.

And she told me so, and she thanked me, which was cool. As a Teaching Elder, those moments are a high point of my vocation.

Which is not to attack others, not to tear down, but to articulate the good story of our faith in a way that can be heard.

Published on June 01, 2015 06:25

May 26, 2015

Bottom Rocker

I've been riding motorcycles now for most of my life, and as long as my carcass can handle it, I intend to keep doing so.

I've been riding motorcycles now for most of my life, and as long as my carcass can handle it, I intend to keep doing so.There are many reasons for it, but primary among them is this: I like the freedom of it.

I'm not in a cage of steel and systems, not wrapped up in fifteen speaker surround and telematics. I cannot be reached by text or by email or by phone or by Facebook. The endless demand of social obligation is on hold, and I am at liberty.

What I know instead is the road and the world around me. I know the heat or the cold. If it's raining, I get wet. I know to be cautious, how to move so that I cause no harm to myself or others.

I am going where I am going. I am doing my own thing in my own time, as Peter Fonda once said.

Which is why I have never understood pack riding. I know, I know, it's probably kind of awesome, you and your tribe rumbling across the landscape like a vast herd of iron bison.

But the more human beings there are, the more rules there are. They begin simply, as all rules do. You think about lane position and formation. You think about pace, not your own, but the pace of the group. There is planning, and more planning, and conversations and negotiation and the next thing you know, there's a committee.

And then the rules and regs pile on, one after another, until suddenly that libertarian vision of open-road freedom looks a heck of a lot like just another bunch of laws.

That was cast into light by the recent deadly explosion of violence between rival gangs in Texas, after an effort to negotiate a truce between the Cossacks and the Bandidos descended into gunplay.

It was such a strange thing. Outlaw bikers, one would think, would be fighting over something nefarious and dangerous. A turf war over meth distribution, perhaps. But knives and guns came out and blood was spilled and hundreds arrested because of...patches. Patches.

Grown up men died over who could wear a Texas "bottom rocker" on their vest, which seems no less bizarre than had Brownies and Campfire Girls gotten into a brawl over their bicycle merit badges.

The irony is mind bending. Here, fiercely freedom-talking "outlaws," and yet they shed blood over the minutia of their own rules, the laws of their tribes, the peculiar pride human beings show in the systems and structures of the social dances we create.

We humans are so weird.

Published on May 26, 2015 05:20

May 22, 2015

The Heart of Being Reformed

Funny thing, how a negative comment can be the best thing get you thinking.

Funny thing, how a negative comment can be the best thing get you thinking.I'd noticed the other day that my rather-less-than-bestselling book on faith and the multiverse had gotten a couple more ratings on Goodreads. The overall rating: a "3," which was where it had been for a while. That had been based on a whopping one reader, who evidently felt sort of meh about it. Now, two new folks had bothered rating it.

One had given it a five out of five. Yay!

The other, a one out of five. Boo!

And of course, the one written review on Goodreads? It's from the person who hated it. Figures. Because those negative things are, of course, where we tend fix our attention. Why don't they like me? What's wrong with me? Snif...

But it's still worth listening, to this human being in their particularity, telling you why they hated it. In this case, they thought the book was going to put multiverse cosmology in the context of the Bible, but it didn't. There was no science in it! There was no bible in it! Evidently, they didn't bother looking at the footnotes. Or the..um..text. Maybe I should have bolded the science parts and put the Bible parts in italics. Or used #hashtags. I don't know. Whichever way, it didn't register. And the whole book was, as far as they were concerned, just standard-issue namby-pamby liberal hoo-hah, in which every faith is the same.

Sigh. At least they put in the effort to write something, eh?

What was illuminating, though, was a particular one of their other complaints, the one directed at me personally. Here I am, a pastor from a reformed tradition. And though I talk about the Bible, the Bible doesn't seem to be my focus in the book. Oh, sure, I reference the Genesis stories. And other Torah. And the Prophets. And the Writings. And yeah, I talk about Jesus, and God, and what the Kingdom of God means, and about the Gospel, with extensive footnotes from the Bible.

But I don't quote scripture in every other sentence I write. I write and tell stories for those who aren't already steeped in the in-group language of my faith. You know, like Ol' Uncle Paul did, up on the Areopagus, when he wanted to connect to people. You know that story, right? Ahem.

Which, as far as my dear reviewer was concerned, meant that I wasn't really Reformed. My faith has to be entirely based in the Bible and expressed in its terms, or I am not upholding the purpose of the Reformation.

This is a good and valid thing to raise, because it's an issue worth talking about. The Reformation, as I understand it, was not primarily about replacing ecclesiastical inerrancy with biblical inerrancy. That was not its purpose, not if it was a God-breathed movement.

Its purpose was to break the grasp of a system that had been corrupted by human power and human grasping. How? By getting those who follow Jesus to realize that they can stand in the same relationship to God that Jesus did. That's the point of the Spirit, that ephemeral third person of our philosophically complex Trinitarian faith.

In point of fact, the only way one can legitimately read scripture is through the lenses of the Spirit. Otherwise, you can bend it and shape it and mangle it any way you see fit. You can focus on irrelevant details. You can justify your own sociopolitical biases, or your own position in the power structure of a culture.

The texts themselves are not sufficient. John Calvin himself was clear on this in his Institutes. Without the Spirit at work in the heart of the believer, those texts have no more authority than the church does when it has God's life and breath crushed out from it.

And as I reflected on that, I found myself grateful to the soul that stirred that reflection. It's a good reminder of what it means to be reformed, and why being Reformed matters so very much.

Published on May 22, 2015 04:24