C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 20

March 18, 2015

3 Ideals That Made Viking Warriors Fearless

1. To Die is to Live

Afterlife to Vikings was a pleasant prospect. Warriors who died bravely in battle had a rather good chance of ending up in Valhalla, Odin’s mead hall where warriors would feast, drink, and battle until the great battle of Ragnarok where they hoped to help their patron god prevail over the forces of evil. Not every warrior made it to Valhalla however, and half of the slain ended up in a different realm named Folkvangr, a land of pleasant springtime fields. The fact that the way one died in battle helped to determine where a warrior ended up after death means every single man would want to fight harder and better than his comrades to make the cut for Valhalla.

2. One’s Fate is Fixed

Vikings were fatalists, but not strict fatalists. They believed they could improve their station in life through force of arms, through travel and conquest. However, when it came to their death, they believed the gods controlled their fate. Death was not to be feared, and its coming was believed to have been preordained. A warrior could improve his chances of entering Valhalla by fighting well and hard, but if the battle he entered was where he was fated to die, he would surely die no matter how hard he fought. The idea that one’s death was out of one’s control—and out of the control of those one fought—liberated Viking warriors from fear.

3. Mind Altering Intoxicants are Always a Good Choice

We know from various sources that the Vikings indulged in heavy drinking, and perhaps even psychedelic drugs (although the evidence is quite shaky in regard to those). Warriors from around the world for thousands of years have known that alcohol can alleviate fear. It was therefore commonplace for the Vikings to drink plenty of alcohol prior to battle to calm their pre-battle jitters. Of course they would not have drunk to the point of affecting their skill; they instead would have drunk only what was necessary to inspire them.

What it All Means

In summary, the Vikings believed the gods controlled their time of death, not the enemy; and even if they faced death, that death was only the beginning. Add some liquid courage and the combination of the above three ideals made for a lethal, frightening spectacle. Warriors from Scandinavia would have (and did) appear fearless, making them all the more fearsome to their foe.

March 14, 2015

Catalyst: How the Saxon Wars may have Sparked the Viking Age.

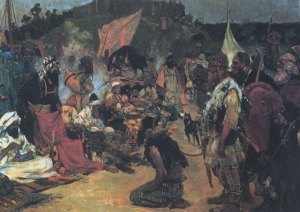

Above is a painting by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville depicting Charlemagne, ruler of the Carolingian Empire, converting an army of defeated Saxons to Christianity. This event took place in 792 when Charlemagne defeated a Saxon army of 3000 men on the shores of the Elbe river where he forcibly baptized them before ordering every prisoner to be drowned. Word of this display of brutality by the Franks reached the Danes of the time, and many scholars believe that it is no coincidence that the Viking Age began during the Saxon Wars. The Saxons were after all pagans who had previously been in regular contact with Scandinavians for trade. The link and association between northern germanic tribes and early Scandinavians is undeniable, and the forced baptism, if we are to believe the Royal Frankish Annals, was meant to warn the Danes of their impending fate should they refuse to convert.

Some historians go as far as to say the attack on Lindisfarne, which occurred in 793, may have been a retaliation for the Frankish conquests. The evidence lies with the account of what the Northmen did to the monks of that monastery. According to Alcuin, one of the primary sources for the attack on Lindisfarne, the Northmen dragged several monks to the beach where they drowned them. This is seen by many as evidence of the Northmen’s acknowledgement of Christendom’s aggressive expansion and barbaric treatment of non-Christians (including forced baptisms). Unfortunately, there is no further evidence to suggest this hypothesis, and therefore it must be treated lightly. However, the people of the time appear to have been much more interconnected than previously acknowledged by academic circles, and those connections would have meant the Scandinavians saw the Christian Empire encroaching on their lands and rightfully retaliated. There are several other causative factors which historians associate with the beginning of the Viking Age, including a change in climate, the closing of Christian trade ports to non-Christians, as well as a population surplus in Scandinavia. It appears many factors played a role in sparking the conquests of the Vikings, but in general it can be heavily associated with the aggressive exploits of the Carolingians.

March 11, 2015

Infographic: A Brief Timeline of the Early Viking Age

March 6, 2015

Fisher Poets Adventure

Last weekend I travelled to Astoria, OR to attend the annual Fisher Poets festival. Many talented poets from numerous places around the U.S. and the world demonstrated their talent at several venues along Leif Erikson Drive. Some expressed sincerity, others humor, and all were a delight to watch.

While in Astoria, I made a few stops by some of the town’s famous sites. First on my list was the Goonies house, which is evidently currently occupied by people who like Israel (note the flag). Although released two years before my birth, The Goonies was a popular pick at my house growing up.

I then stopped by the iconic John Jacob Astor Elementary school, the filming location of the movie Kindergarten Cop starring my favorite movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger (don’t judge). Here I am screaming at the sky before heading to my car to get my ferret.

Now back to writing about the Vikings. Be sure to check out my second novel, The Oath of the Father.

Skål!

March 2, 2015

Author Update 3/2/15

My second novel has finally been released, and I must say I am much prouder of how it turned out than the first. I love my first novel, it was after all my first. But I feel I found my voice in my second novel, and I believe it will both engage and satisfy my fans, as well as new readers. On the heels of its release, I am continuing to synthesize the next installment of the Kindred of the Sea series, which will focus on Abriel’s eldest daughter Asa as she learns the nuances of leadership in a patriarchal world. The novel will again take readers to Ireland, but this time in more depth as the Vikings begin a major invasion. It will parallel an invasion of Brittany in the same period as the Carolingian Empire begins to lose cohesion. It will be fun to write, and hopefully to read.

A few announcements:

1. I am on track toward my goal to finish my first trilogy before the age of 30. In fact, since that date is three years away, I should be well into the second trilogy by then. My publisher certainly has no objections. For those who are wondering, the Kindred of the Sea series is planned out for six books, with the potential for 9 depending on the success of the second trilogy. I have all the research for the series finished, it is a matter of putting the stories onto paper.

2. At the request of my publisher, I am currently working on a new edition of The Line of His People, with a small amount of re-working, and another edit by my editor. I admit the first novel was rushed (I wanted it published before beginning the school year of 2013-2014 as a teacher), so we will be making a few improvements in the near future. I do not have a firm date for when this will happen, but we are working on it right now.

3. My blog is narrowing in on 100k views, WHOA! I did not expect to each that number in such a short time! Thanks to everyone who has stopped by.

I thank all of my fans around the world and hope you enjoy my second novel! Leave me a review if you can, thanks! And remember, these books are written at the Young Adult level, so if you have children, nieces and nephews, or grandchildren, feel free to share Abriel’s story with them.

Sincerely,

~C.J. Adrien

February 25, 2015

The Truth About Viking Armor: No Horns, No Uniformity Either.

10th Century Chieftain

While the History Channel would have us believe they were a leather-clad biker gang akin to the Sons of Anarchy, the real Vikings would have had a much more diverse wardrobe. It is first important to understand that the Viking Age lasted almost three centuries, during which styles and clothing changed. Early raids in the 8th century were carried out by small groups of free warriors, banded together for the purpose of pillaging and acquiring wealth to take home. One hundred years later, the West came under siege as ambitious warlords repurposed their warriors for invasion requiring a refitting of their battle gear to withstand the test of large confrontations. This begs the question: what did they really wear?

Early on during the Viking Age, the warriors of various raiding parties would have worn what they could afford, as well as what worked at sea. Anyone who has worn leather knows that salt water is incredibly corrosive to it, making it tough and unwearable. Therefore leather would have been sparse. A more common type of clothing for the era was cloth: heavy interweaved fabric designed to absorb slashing blows (but not stabs). Cloth would have kept sailors warmer at sea as well, and anyone who has ever sailed knows how cold the ocean’s winds can be, even on a hot, sunny day. Cloth unfortunately does not leave much behind for us to find or add to the archeological record. We may only deduce that it was the clothing of choice because of availability, and because of the universal use of cloth protection across the western world at the time.

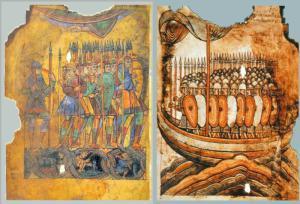

Later in the Viking Age the Vikings diversified their wardrobes. The riches they brought home from raids increased the wealth of the average free warrior, allowing him to invest in heavier pieces of equipment. Wealth was not the only import to Scandinavia either. Vikings brought home new technologies for farming and building, as well as weapon making. Does this mean they all began to wear mail and steel helmets? Perhaps not, but there is evidence to suggest that some armies at least may have done just that: equip everyone with the best armor money could buy. Below is a depiction of a 10th century attack on Guérande in which the Vikings (in a ship on the right) are all equipped with shield, helmet, hauberk, and lance. (click to enlarge)

The above drawing is of the 10th Century invasion of Brittany, which led to a 20 year occupation of the region, including the cities of Rennes and Nantes. In fact, the Breton leaders who expelled the Vikings only did so after they had craftily turned the Normans in Normandy against the Normans in Brittany. What this evidence tells us is that the Vikings repurposed their armies to suit their ambitions. Early raiders could not stand up to the better equipped Frankish armies of Charlemagne and Louis I, but as they increased their wealth and shifted their ambitions, they became better equipped and more organized. Depending on the region they attacked, the Vikings adapted to their enemy and adopted forms of arms and armor influenced by those who they fought. For example, on the island of Groix in southern Brittany a Norman burial dating to the mid-10th Century yielded twenty-four shields of a unique design which historians suppose were built by the occupying army. It is demonstrative of the willingness of the Northmen to improve their equipment, and also shows us that their equipment would have been diverse across the world.

So what did they really wear? The answer is that they wore what suited them for the time and place. In the West, they began to resemble their British, Breton, and Frankish neighbors. In the East, they began to resemble the Byzantines and the Slavs they occupied. Uniformity was not their strong suit, and this was perhaps their secret to success: adaptability. There is a great deal of conjecture and interpretation in dealing with what the Vikings wore, and there is still a great deal that we do not know. We do know that as the Viking Age progressed, the attire became more region-specific. A viking in Brittany in the 9th Century would have appeared different from a Varangian in Constantinople in the 10th Century. The only universal piece they all wore was a beard; it was cultural and several sources mention how shameful it was if a free warrior could not grow one.

Sponsored Ad

February 24, 2015

The Curious Case of al-Ghazal

In the 9th Century a Moorish ambassador named al-Ghazal set sail for foreign lands to study a people called the Majus. His account tells of his voyage across the ocean to a splendid island described as having lush, flowering plants and abundant streams leading to the ocean. For years historians struggled to gather consensus on who these Majus may have been, but more recently it has become accepted that they were indeed the Vikings. Unfortunately, the consensus ends there. Some scholars believe the embassy of al-Ghazal to have taken place in Denmark, whereas others propose he had visited the court of Turgeis, a powerful warlord who ruled over much of Ireland. His account is compelling and offers a tremendous volume of information about the Majus many scholars believe no chronicler of the time could have fabricated.

The source for al-Ghazal’s embassy to Ireland is a document produced by Abu-l-Kattab-Umar-ibn-al-Hasan-ibn-Dihya, who was born in Valencia in Andalucia, about 1159 A.D. The facts and anecdotes in the story were derived from Tammam-ibn-Alqama, vizier under three consecutive amirs in Andalucia during the ninth century who died in 896. Tammam-ibn-Alqama had allegedly learned the details directly from al-Ghazal and his companions. The only manuscript of ibn-Dihya’s work was acquired by the British Museum in 1866. It is titled Al-mutrib min ashar ahli’l Maghrib, which translates to An amusing book from poetical works of the Maghreb.

The entire account is quite possibly true, and quite possibly accurate, but the subject remains debated. Nevertheless, it appears the Moors took an interest to the Vikings, no doubt a result of their early interactions with Viking explorers and tradesmen. If true, this account demonstrates yet another interaction between the Vikings and the Muslim world previously unknown to us, and is telling of the openness of Norse culture to visitors. In the account, al-Ghazal spends a great deal of time with the wife of the king of the settlement who he takes a strong liking to. The document is compelling evidence that a Muslim visited Ireland in the 9th Century and, according to his account, got very cozy with the king’s wife during his stay.

Source:

Allen, W.E.D. The Poet and the Spae-Wife. Titus Wilson and Son, Ltd. London, 1960.

Sponsored Ad

February 20, 2015

Vikings Season 3: Where Are All Their Helmets?

Ragnar and company were at it again in the first episode of Season 3, and the producers did well to throw us all back into the thick of battle. It was entertaining, and the actors left us with the impression that there is more to the story than meets the eye.

Yet I am left wondering why the Vikings were given such a light wardrobe compared to their admittedly much better equipped foe. Particularly, where are all their helmets? We know they wore them, and we know helmets were a rather central piece of armor warriors typically did not do without. What did a Viking’s helmet look like? It turns out, they varied widely among the Norsemen who designed their helmets with influences from the places they traveled. For example, the Rus’ (Swedish Vikings) wore more pointed helmets with an Eastern flare, influenced by the Byzantines and other peoples they encountered in the East. In the West, they wore more conical helmets much more closely related to the helmets the Carolingians wore. Pictured below is an example of a helmet found in Norway, one of the rare examples ever found.

Why then did the History Channel decide to omit helmets from their representation of the Vikings? Who made that call? In their defense, helmets are one of the rarest forms of armor found in archeological digs, meaning they perhaps were not universal. This could be the reason the producers decided to forgo giving Ragnar the famous “dragon head” look with a low-swooping visor and conical helmet. It is not wrong to suppose that the average free warrior may not have had the resources to afford the more expensive forms of armor such as a mail hauberk, steel greaves, or a helmet. It is not necessarily correct either. What we do know about the proliferation of steel armor is that by the Norman conquest of England in 1066 they all wore conical helmets and an array of mail and leather armor. We unfortunately do not have any visual depictions of warriors from that time except for the Bayeux Tapestry, so it is difficult to say with any certainty whether or not the Vikings commonly wore helmets, or when such a trend may have begun. Therefore, it is up to interpretation.

In my opinion, they all would have worn head gear of some sort. A warrior culture as developed and seasoned as the Viking Age Scandinavians would not have been so foolhardy as to believe themselves exempt from the dangers of initiating battle without proper attire. Perhaps helmets are difficult to find because they were more commonly made of leather, a proposed theory to the absence of helmets in the archeological record. I am also of the opinion that mail hauberks were much more common than previously though among the Vikings because they were readily produced in the Carolingian Empire, a frequent target of raids. Mail was also produced readily in the wealthy Byzantine Empire, which meant the Rus’ would have had access to such armor as well. Pictured below is what many (if not most) believe to be a more accurate wardrobe for a Viking warrior. Keep in mind, the figure below represents what would have been a wealthier warrior, perhaps a chieftain or Jarl.

Should we be concerned about the lack of headwear? Anyone who has had any experience in contact sports or combat or otherwise knows that the head is the first and most important part of the body to protect. Ancient peoples knew this as well. The Romans knew this, the Carolingians knew this, the Ancient Egyptians and Assyrians knew this. Helmets were not a new thing. I believe the Vikings would have known better as well. I am careful to say that this is my opinion because, as I mentioned above, helmets are still an incredibly rare find among Viking Age artifacts, which may mean the History Channel has it right. I am open to the possibility that my conclusion is wrong—as all historians should be. Nevertheless, a Viking battle would likely have looked more like this:

Or perhaps the choice to omit helmets in the show was made after a fight between the wardrobe department and the hair stylists. After all, we wouldn’t want Rollo’s beautiful hair to be smushed under a helmet, would we?

Sponsored Ad

February 19, 2015

The #1 Thing History’s Vikings Got Right

To the history buffs who believe the show Vikings on History Channel to be an insult to the true peoples of Viking Age Scandinavia: relax. Yes, the show is a blunder in several key areas of history, particularly concerning the clothing they wear and much of the clothing their opponents wear (I am referring specifically to the ill-placed Conquistador helmets of the soldiers in Northumbria). And yes, the teasers in which Ragnar is supposedly going to attack Paris—an event we know to have taken place in 845 A.D.—is completely nonsensical since the show already placed him at Lindisfarne—an event which we know to have taken place in 793 A.D. Perhaps Ragnar is secretly an immortal Elf from Elfheim, because the show is implying he is going to be in his 70’s or 80’s in season 3 which no new haircut can accurately portray. But here is why none of it matters: the one thing History Channel did right was to make sure the show was regarded as fiction.

The first thing you may notice when reading up on the history of the Vikings is that the legendary hero Ragnar Lodbrok (hairy breaches) is not actually represented in the show. Vikings’ protagonist is Ragnar Lothbrok, a similar sounding name, but not quite right. The producers made this distinction because as it turns out much of what we know about the Viking Age is highly subjective and up for interpretation. The Sagas from which Ragnar’s story is extracted are bit like the Christian Bible—they are a collection of stories perhaps written about real people, but written decades and even centuries after the fact. This makes the sagas a poor source of information about the events of the Viking Age, but they are a wonderful insight into storytelling and culture. Therefore, Ragnar Lodbrok remains what historians refer to as a “legendary king.” In other words, there is no reliable, definitive proof to say that he actually existed. Ragnar is not alone. There are dozens of legendary figures whose true identity is up for debate. The producers of Vikings have thus created a fictional character based on a legendary figure, meaning they had no intention of sticking to a strict, history-based timeline from the start.

With all of this in mind, it is important for history buffs, Viking Age historians, and other connoisseurs of the Vikings to ignore the historical relevance of anything brought up in the show. They’re not trying to get it right. The series is doing exactly what it was intended to do. For the producers, it is generating interest in a specific field of history. To the studios, it’s making money. For the audience, it is a captivating drama with plenty of action to satisfy our base desires. My recommendation is to watch, enjoy, discuss, and have fun. If historical accuracy is what you’re looking for, try a book. Historical Fiction authors are much more obliged to stay within the rigid confines of history because their audience is generally more cultivated and likely to catch them on an error. Plus, a book leaves much more up to the imagination, so the Vikings you read about are going to be much more accurately represented in your mind than those you see on TV.

Sponsored Ad

February 17, 2015

3 Places You May Not Know the Vikings Visited

When we think of the Viking Age, we think of the invasions of England and Ireland, of the exploration of the Eastern Steppes, and of the attacks along the coasts of Western Europe. Recently, historians have expanded this view through discoveries which have expanded what we know about the breadth of influence the Vikings had across the world. You may know that the Vikings visited Spain, and even sacked Seville in the 9th Century. You may also know that they venture far enough East to end up in Constantinople where they were hired as mercenary fighters. What you may not know are some of the other less known places the Vikings visited such as Sicily, Morocco, and even Baghdad.

Sicily

The Vikings’ visit to the Italian Peninsula was short lived. We know from several sources that one particular expedition initiated the Norse exploration of the Mediterranean Basin, the first of several. A man named Hastein, a supposed son of Ragnar Lodbrok, set out in the 850’s A.D. with thirty ships to sail around Iberia, through the straight of Gibraltar, and into the Mediterranean. This first expedition was not considered all that successful. Although they sacked Seville and made away with plenty of plunder, their fleet was ambushed in the Mediterranean by the a Muslim navy which made quick work of them. Hastein is believed to have narrowly escaped the attack with half a dozen ships and dumped most of their plunder to be able to outrun their attackers. They may have ventured as far as Italy, but the account is vague so we are not entirely sure. However, the report Hastein brought back to the North inspired others to attempt to raid the Mediterranean whose coastal settlements were thought to be wealthy. As early as 999 A.D. a more aggressive invasion began in Sicily led by Norman Brigands (Vikings from Normandy) returning from pilgrimage who found the island to be an attractive target for invasion. They began what would become the Norman Invasion of Sicily. After a long but successful campaign the Normans conquered Sicily and established the Norman Kingdom of Sicily which remained under their control well into the 13th Century. In fact, William the Conqueror’s descendant Henry II, known as the father of the Angevin Dynasty in England, maintained heavy influence over Sicily, which his son Richard the Lionheart used to launch his crusade in the Middle East.

Morocco (Berbery)

Hastein’s expedition also attempted to attack Muslim settlements in North Africa. It is this attack which historians believe allowed the Muslims to gather their navy to confront the Norse raiders as they entered the Mediterranean. While they left little trace of their time in North Africa, their sudden appearance alerted the rest of the Islamic world to their threat. Word of their bold and hostile actions are believed to have reached as far as the ruler of Constantinople. While not a singularly important event, the mystique it would have created around the Norsemen may have helped to further their reputation in the Muslim and East Christian world.

Baghdad

The Rus, a tribe of Swedish Vikings who travelled East along the Dnieper and Volga rivers, established extensive trade routes which reached as far as Baghdad. Their trade took them through Constantinople and into the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as through the Caspian and Black Seas, even through the kingdom of the Kazhars whose lands included the modern day country of Georgia. We know they must have travelled as far as Baghdad from several sources, including sources left by the Byzantines, the Muslims in Baghdad, as well as archeological finds in Russia and Scandinavia in which there have been coins and other trade goods produced specifically in Baghdad. What did the Rus trade with the Muslims? They offered one of the most luxurious types of good: furs.

Sponsored Ad