C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 18

August 10, 2015

3 Must-Do’s for Aspiring Writers of Historical Fiction

1. Create a timeline of dates.

Historical fiction is more rigid than other fiction genres because there is the expectation by readers that some (if not most) elements in the story will have been based on true events. The closer to actual history you are the better. That is why it is important for authors of historical fiction to create a timeline of the history behind their story first. Add the fictional elements of the story later. Failure to create a timeline may lead to an incoherent story with holes in both the history and the narrative.

2. When it comes to names, simpler is better.

The English language as it is today is not all that old. Considering this, many historical fiction novels will inevitably be written about people who spoke a different language. This can lead to a plethora of complicated, non-anglophone names that may be challenging to readers to remember. This is why when assigning names to fictional characters it is advisable to chose names that are both easy to pronounce and to remember. Historical characters are of course the exception here, and their names cannot (or should not) be altered. For example, in my second novel my protagonist encounters an Irishman by the name of Muiredach Mac Ruadrach. It’s not a name that exactly rolls off of the tongue. His name I cannot change because he was a real person. What I am able to control are the names of my characters, such as Kenna, which is both an old Norse name and, luckily, a modern name used in Anglophone countries and therefore easy to remember.

3. Find your world-building balance.

World-building is something you hear often in science fiction and fantasy circles. But historical fiction similarly requires a great deal of setting development to help transport readers to the time period of your writing. This begs the question: how much time should I devote to world-building? The answer depends on the intended audience. For example, an author the likes of Bernard Cornwell will spend ample time and space describing some of the more intricate details of his setting. On the other hand, if one is writing for a Young Adult audience, the world-building may need less depth so as to not bore readers. It is important that you consider your audience when developing your world-building. You would never expect J.K. Rowling to droll on for two pages about the shade of green painted on the wall, whereas you would never expect Bernard Cornwell not to. Find your balance for your audience.

August 3, 2015

5 Major Factors That Ended the Viking Age

The internet is abound with a multitude of theories on why the Viking Age began. Why it ended is equally as interesting because it was a pivotal segue into the medieval period so romanticized by 19th Century historians. Scandinavian raiders ruled the seas and rivers of Europe for hundreds of years, yet their maritime hegemony did eventually end, although their seafaring technology would not be bested for another long while. Why did the Viking Age end? What led to the demise of their notorious raids? The following are brief summaries of five of the most pivotal themes and events that contributed to the end of the Viking Age. Keep in mind, however, that the end of the Viking Age was the result of a vastly complex interweave of issues and events and therefore this list is neither all-encompassing nor exhaustive.

The Christianization of Scandinavia

Over the course of their three-hundred-year-long reign of terror, a less pronounced force gradually chipped away at the Vikings’ roots. Charlemagne’s Christian empire sought to convert the world to their faith through force of arms, but he stopped short of Denmark and died before launching any significant invasions of it. Spared the constraints of a Frankish occupation, Danish rulers launched some of the most memorable raids of their day. However, they were not a unified people. Frequent civil wars plagued Jutland (the main Danish kingdom of the time) in the early 9th Century and some of the claimants to the throne sought support from their neighbors to help them ascend to power. Harald-Klak, one such claimant from the early 9th Century, allied himself with the Carolingian emperor Louis and even received baptism to show his dedication to the conversion. The Franks in turn sent weapons and supplies to the Danes loyal to Harald. These early conversions for political reasons were not initially considered a serious commitment, but they began a trend wherein they allowed the Christians to begin incursions into Scandinavia.

Later conversions were more aggressive. Missionaries in the 10th Century continued to convert Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes en masse. Certain rulers, such as Harald Bluetooth, made Christianity their official religion and instituted laws requiring their subjects to convert. By 1066, the date used by historians to demarcate the end of the Viking Age, a majority of Scandinavia was Christian.

The Peace and Truce of God

In the 11th Century, the Roman Catholic Church felt that the incessant, bloody wars between the various European kingdoms were a bane on their efforts to spread the true faith. Violence was a real existential problem for them at the time. To abate some of this violence, they instituted two edicts, dubbed The Peace of God and The Truce of God. These edicts banned violence between Christians under threat of excommunication. Both reforms helped to end the Viking Age by formally dissuading an increasingly christianized Scandinavian population from launching raids on fellow Christians. This did not entirely stop the flow of raiding parties, but they gradually diminished as time passed.

The Feudal System

As the feudal system took hold and spread across Europe, the societal structure which had allowed free men to sail to new lands to raid vanished. What were once considered free men became the indentured servants of the new feudal monarchs who depended on their labor to generate income. Where all men were once required to learn how to fight, they were now dissuaded from doing so. As part of a vast move to consolidate power, the monarchs of Scandinavia instituted reforms to convert their subjects into servants, much as their southern European neighbors had done. Putting together a crew to raid a faraway land became less and less feasible.

The Assimilation of Settlers Into New Societies

The Viking Age saw its twilight when the lands they had once raided were settled and defended by their own kin. This occurred in Britain, Ireland, Russia, France, among several others. Normandy is a prime example of how the Vikings assimilated into the culture of the people who had previously owned the land they settled. By 1066, the Normans were francophone (old French) and loyal to the French king. They obeyed the commands of the Pope and answered to the local church. They retained some vestiges of their Viking past and, arguably, those cultural traits later contributed to the political climate in England that led to the Magna Carta. But for all intents and purposes, the men who invaded Britain in 1066 were no longer Danes, they were French.

A Final Blow

One Scandinavian monarch defied the tide of history and continued to raid as his forefathers had done. This last raider, king Harald Hardrada, built a reputation for himself as a formidable warrior and tactician. In 1066 he attacked England as one of the many rival claimants to the English throne. He was killed at the battle of Stamford Bridge by the forces of Harold Godwinson. Thus ended the life of the last infamous Norse raider; thus ended the Viking Age.

Interested in the Vikings? Check out my novels about the Vikings in France:

Why did the Viking Age End?

The internet is abound with a multitude of theories on why the Viking Age began. But why it ended is equally as interesting because it was a pivotal segue into the medieval period so romanticized by 19th Century historians. Scandinavian raiders ruled the seas and rivers of Europe for hundreds of years, yet their maritime hegemony did eventually end, although their seafaring technology would not be bested for another long while. Why did the Viking Age end? What led to the demise of their notorious raids? The following are brief summaries of several of the most important issues to answer this question. Keep in mind, however, that the end of the Viking Age was the result of a vastly complex interweave of issues and events.

The Christianization of Scandinavia

Over the course of their three-hundred-year-long reign of terror, a less pronounced force gradually chipped away at the Vikings’ roots. Charlemagne’s Christian empire sought to convert the world to their faith through force of arms, but he stopped short of Denmark and died before launching any significant invasions of it. Spared the constraints of a Frankish occupation, Danish rulers launched some of the most memorable raids of their day. However, they were not a unified people. Frequent civil wars plagued Jutland (the main Danish kingdom of the time) in the early 9th Century and some of the claimants to the throne sought support from their neighbors to help them ascend to power. Harald-Klak, one such claimant from the early 9th Century, allied himself with the Carolingian emperor Louis and even received baptism to show his dedication to the conversion. The Franks in turn sent weapons and supplies to the Danes loyal to Harald. These early conversions for political reasons were not initially considered a serious commitment, but they began a trend wherein they allowed the Christians to begin incursions into Scandinavia.

Later conversions were more aggressive. Missionaries in the 10th Century continued to convert Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes en masse. Certain rulers, such as Harald Bluetooth, made Christianity their official religion and instituted laws requiring their subjects to convert. By 1066, the date used by historians to demarcate the end of the Viking Age, a majority of Scandinavia was Christian.

The Peace and Truce of God

In the 11th Century, the Roman Catholic Church felt that the incessant, bloody wars between the various European kingdoms were a bane on their efforts to spread the true faith. Violence was a real existential problem for them at the time. To abate some of this violence, they instituted two edicts, dubbed The Peace of God and The Truce of God. These edicts banned violence between Christians under threat of excommunication. Both reforms helped to end the Viking Age by formally dissuading an increasingly christianized Scandinavian population from launching raids on fellow Christians. This did not entirely stop the flow of raiding parties, but they gradually diminished as time passed.

The Feudal System

As the feudal system took hold and spread across Europe, the societal structure which had allowed free men to sail to new lands to raid vanished. What were once considered free men became the indentured servants of the new feudal monarchs who depended on their labor to generate income. Where all men were once required to learn how to fight, they were now dissuaded from doing so. As part of a vast move to consolidate power, the monarchs of Scandinavia instituted reforms to convert their subjects into servants, much as their southern European neighbors had done. Putting together a crew to raid a faraway land became less and less feasible.

The Assimilation of Settlers Into New Societies

The Viking Age saw its twilight when the lands they had once raided were settled and defended by their own kin. This occurred in Britain, Ireland, Russia, France, among several others. Normandy is a prime example of how the Vikings assimilated into the culture of the people who had previously owned the land they settled. By 1066, the Normans were francophone (old French) and loyal to the French king. They obeyed the commands of the Pope and answered to the local church. They retained some vestiges of their Viking past and, arguably, those cultural traits later contributed to the political climate in England that led to the Magna Carta. But for all intents and purposes, the men who invaded Britain in 1066 were no longer Danes, they were French.

A Final Blow

One Scandinavian monarch defied the tide of history and continued to raid as his forefathers had done. This last raider, king Harald Hardrada, built a reputation for himself as a formidable warrior and tactician. In 1066 he attacked England as one of the many rival claimants to the English throne. He was killed at the battle of Stamford Bridge by the forces of Harold Godwinson. Thus ended the life of the last infamous Norse raider; thus ended the Viking Age.

Interested in the Vikings? Check out my novels about the Vikings in France:

July 30, 2015

Can You Spot the Impostor? Three Truths and One Lie About the Vikings.

Of the four statements below, three are true and one is a lie. Can you spot the lie? (Scroll to the bottom to reveal the answers.)

1. The Vikings Shooed Away Eclipses.

Vikings believed that Ragnarok would come about when the two wolves, Skoll and Hati, devoured the Sun and the Moon. Skoll chased after the Sun and Hati chased the Moon. It was believed that during an eclipse Skoll had caught up with the Sun and the only way the men of Midgard could help was to create as much noise as possible to scare off the wolf.

2. The Viking Diet Changed from Fish to Meats and Breads While in England.

During their conquest of the British Isles, the land armies of the Danes adopted the local delicacies in favor of their traditional diet. In Scandinavia, the primary source of protein for coastal settlements was Herring, whereas in Jorvik (modern day York), they ate more meats and breads acquired from local farms.

3. The Vikings Who Fled to Iceland Were Exiles and Criminals.

The original migration to Iceland consisted of the outcasts of Norse society. The first expedition was even led by a woman who had notoriously slain her husband in the middle of the night in lieu of a divorce. Other Scandinavian kingdoms openly expressed their disdain for the new refuge of societal rejects, but made no effort to stop it.

4. Vikings Traded Black Slaves in Ireland.

During his expedition to the Mediterranean, the warlord Hastein initiated trade with the Moors of North Africa. There they traded various goods, including slaves, with the locals. According to two sources, he later traded these slaves in Ireland before returning to his plundering in the Loire River Valley.

Do you know which one is wrong? Scroll down to see if you’re right!

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

#1: True:

In the Poetic Edda, particularly in the Grimnismal, there are instructions on how to ward off Skoll during an eclipse.

#2: True:

A coprolite found in York has revealed that the diet of the men in Jorvik consisted mostly of breads and meats. It also revealed that the man who had deposited it suffered from a bad case of intestinal worms. Read about the coprolite HERE.

#3: False:

The first settlers who travelled to Iceland were not criminals and exiles. Instead, many were communities who were pushed out of their homelands by war, famine, and many to flee the aggressive christianization of Scandinavia.

#4: True:

Hastein accomplished a great many things in his life, including the trading of black slaves to northern kingdoms. Read more about Hasten HERE.

As always, my series titled Kindred of the Sea is available for purchase on Kindle. Click the cover below to shop now!

July 27, 2015

Three Norse Customs that Christianity Killed.

When Christianity spread across Scandinavia during the Viking Age, it changed many Norse cultural norms. The following are three of the most notable changes that took place as a result of their Christianization.

1. Grooming.

Reindeer Antler Comb from Ribe, circa 8th Century

Reindeer Antler Comb from Ribe, circa 8th CenturyPrior to converting to Christianity, Norse culture valued good grooming habits. We know this from several sources, including both Christian and Muslim texts, as well as archeological finds of combs, washbowls, and saunas. Christianity, however, viewed Norse grooming habits as signs of vanity. In Christendom, it was required of some people, especially clerics, to never bathe. In fact, monks actually thought the dirtier they were, the holier they were because they were rejecting vanity. As Christianity spread across Scandinavia, the Scandinavian people joined the rest of Christendom in their smelliness. Read more about Norse grooming.

2. Religious Tolerance.

The baptism of Harald-Klak of Denmark.

The baptism of Harald-Klak of Denmark.History has shown time and again that polytheistic religions tend to be more tolerant of other faiths. Norse paganism was no different. Their tolerance for other belief systems may have contributed to their Christianization as they may not have seen Christianity as a threat. Christ would have just been another deity among the many in the world to them. Christianity tends to be intolerant of other religions as all the Abrahamic religions are. And once Christianized, the once tolerant Norse people became as intolerant of other religions as the rest of Christendom. Read about the Norse culture of learning.

3. Separation of Church and State.

Charlemagne overseeing the massacre of the Saxons on the Elbe.

Charlemagne overseeing the massacre of the Saxons on the Elbe.Prior to Christianization, Norse culture did not separate religion from politics. Religious festivals and observances were the duty of the Jarl or Chieftain of the community to organize and carry out, sometimes aided by other religious figures (with the temple at Uppsala as the main exception). Christianity put an end to this tradition and passed the duty of religious observance to clerics and the Church rather than to the leader of the community. This change took power away from local leaders and gave more power to the church. The separation of church and state was originally devised to consolidate power within the church because most governments were unreliable and changed leadership frequently. Not until much later in the medieval period would more powerful, stable monarchs begin to take a more active role in the church, eventually becoming figureheads associated with divinity.

Interested in the Vikings? You will love my novels! Buy my first in series below:

July 21, 2015

What Is the Danevirke?

Anyone interested in the Viking Age should know about this hugely important edifice which has over the centuries served as both a physical border and an ideological one. The Danevirke is a series of ditches and fortifications along the southern border of the Danish peninsula, effectively separating it from the rest of the continent. Archeological research estimates the first sections of the Danevirke as having been build as early as the sixth century. Current scholarship theorizes that such fortifications were encouraged by constant conflict between the inhabitants of the peninsula and their southern germanic neighbors. In fact, this conflict is thought to have led to the exodus of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes to Britain. This first construct has more recently been identified as a possible shipping channel between the Baltic and the North Sea rather than a fortification (to read about the new discoveries, CLICK HERE).

Later evidence of further fortification begins in the early 9th century in the Royal Frankish Annals in which the Danish king Gudfred is said to have rebuilt the Danevirke to repel Frankish invasion. Archeological finds place more extensive construction in the time of Harald Bluetooth, and scholars disagree over which monarch was most responsible for the expansion of the more extensive fortifications that earned the Danevirke its later reputation as a symbol of the separation between the Danes and their southern Germanic neighbors.

During the Viking Age, the Danevirka was an important construct for the Danes of Jutland who felt the very real threat of invasion by the Frankish Empire. Although Charlemagne never materialized a full scale invasion, his son Louis the Pious sent frequent bellicose incursions toward Jutland, but never launched a frontal assault on the Danevirka. Luckily for the Danes, after the death of Charlemagne the Frankish Empire was plunged into repeated civil wars, taking the pressure off of their border and allowing them to begin their own foreign exploits in Normandy, Britain, and Brittany. In more simple terms, the Danevirke prevented the invasion of Jutland by the Franks and allowed the Viking Age to have actually happened.

Further reading:

McKitterick, R. (2008). Charlemagne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scholz, B. (1972). Carolingian chronicles: Royal Frankish annals and Nithard’s Histories. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

The Danevirke is mentioned in my historical fiction series about the Vikings. CLICK HERE to read it.

July 15, 2015

The Clergymen Who Fought Back Against the Vikings

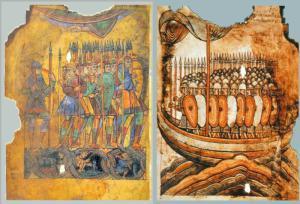

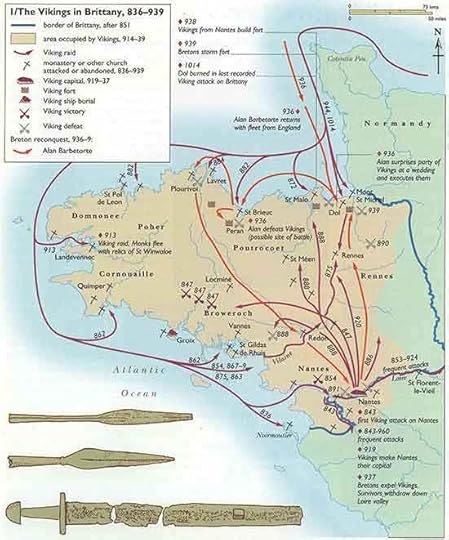

Source: Historical Atlas of the Vikings, by John Haywood

Source: Historical Atlas of the Vikings, by John HaywoodIn 799 A.D. the world turned upside down for the clergymen of the Saint Philbert monastery, located on the modern day island of Noirmoutier in France. Following the first attack, the monks retreated to the continent where they waited for a sign from God to decide on what to do next. The Archbishop of Tours, who at the time was the top official for the region, approved the construction of a satellite priory on Grand-Lieu lake, a place distant enough from the coast to avoid being sacked. It took nearly a decade before the monks returned to the island to assess the damage done to their monastery. With renewed approval from the archbishop, the monks rebuilt thinking the attack had been a singular event.

They were wrong.

For the next two decades, the Northmen attacked the island repeatedly. The monks decided to split their time between their two places of worship, spending their winters on the island and their summers on the continent to wait for the raiding season to pass. They carried out this commute until the early 830’s when, spurred by the ineptitude of the Carolinian Empire who were plunged in civil war, the Archbishop of Tours took it upon himself to ensure the safety of the clergy.

In 834 A.D. the church leadership funded the construction of a castrum on the site of the Saint Philbert monastery and hired a garrison of conscripted soldiers to defend it in summer. According to the firsthand account of an anonymous monk under the pen name of Ermentarius, the summer the castrum had been finished, the Northmen made their appearance. What the monks had not anticipated was the calibre of man who they were fated to face.

The warlord Hastein (click to read about Hastein) made his first incursion into the Bay of Biscay that summer with the hopes of finding riches described to him by his kin in Ireland. He landed on the island and found the new fortifications in place. Immediately, he set his men upon the wooden wall and within a day they managed to breach the defenses. With their conscripts dead or fleeing, the monks attempted to save themselves to no avail.

In the aftermath of the battle, the monks abandoned the island definitively. To their chagrin, the castrum they had build served as the perfect base for Hastein who used it to store his loot and launch raids across the region. The Annales D’Angoulême document, which recounts the sack of Nantes in 843 A.D., describes the island as a permanent base for the Northmen and later in 847 A.D. as the base from which the Vikings launched a mainland invasion of Brittany.

In their attempt to fend off the Northmen, the clergymen appear to have only encouraged them.

My Kindred of the Sea series is specifically about the Viking raids and invasions of Brittany, beginning in 799 and, when the series is finished, ending in the mid 10th century.

July 9, 2015

Did the Vikings Wear Helmets?

We know for sure that the Vikings did not have horns on their helmets. Yet recently a debate has emerged in regards to whether or not the Vikings wore helmets into battle at all. Two divergent camps continue to argue over the prominence of protective headgear during the Viking Age, and neither appears to be gaining the upper hand. This is because from a scholarly position, we simply do not know. Only one Viking Age helmet has ever been recovered in archeological digs, leading many to suspect they were uncommon. The following are the two sides of the argument on whether or not the Vikings wore helmets.

The argument against helmets:

Archeologists have only recovered one helmet (pictured below), dating back to the 9th century, which likely means they were uncommon. Other items such as swords, axes, various articles of clothing, ships, and even maille hauberks have been more commonly found in Viking Age burials and dig sites. The fact that helmets are such a rare find is a strong indication that, at the very least, iron helmets were not commonly made or utilized. Until more artifacts are found, the presumption should be that Viking Age Scandinavians did not commonly wear headgear.

The argument for helmets:

The lack of archeological specimens of helmets does not necessarily indicate that they were not commonly used. Metal was in high demand in the Viking Age, and even more so later in the medieval period. Quality metals, such as those found in helmets, may have been melted down, refined, and repurposed, which may explain the lack of helmets in the archeological record. There is evidence in the historical record, such as in the representation of a Viking attack on Guérande in the Annales D’Angoulême (pictured below), in which the Norse warriors are all drawn as having protective head gear in one form or another. This is indicative that the Vikings did wear headgear that simply did not survive to today.

Who is right?

There is not enough information to make a definitive assessment on the matter. A lack of helmets in the archeological record poses a particularly perplexing argumentative problem because it neither proves nor disproves the use of helmets by the Vikings. This problem is further compounded by artistic representations by historians from the time whose artwork may or may not be accurate, and there is no way of knowing for sure. Short of a lucky find of a mass grave containing helmet-clad warriors, we may never know for sure. Thus, for now, it is up to the individual’s interpretation of the evidence to decide, and the debate shall continue.

My second novel, The Oath of the Father, is FREE on Kindle this weekend only. Join the Vikings on a global adventure today!

June 24, 2015

Leif Erikson Mud Wrestled With Sasquatch?

I enjoy watching Sasquatch shows—not because it’s good history or science, but because I enjoy watching the folks on the Discovery Network, who have aired countless shows investigating the viability of the theory that a large primate stalks the vast untouched forests of the Americas, make fools of themselves. And there’s something enjoyable about the prospect of adventuring into the wilderness for a weekend, although most of us call that camping, not “Squatching.” These shows should have nothing to do with history or the Vikings, yet the macaques who produced one such show had the audacity of claiming that Leif Erikson had encountered Bigfoot, and that the evidence for it lies in the sagas.

Oh dear…

Could this have been true? Did they find something that I missed? In fact, no.

It turns out the show decided to reference a bad translation of the sagas by one Samuel Eliot Morison who, in his title work The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages A.D. 500-1600, translated the Norse’s description of the natives in Newfoundland as, “horribly ugly, hairy, swarthy, with great black eyes.” From this translation, which is unique among the others, Bigfoot “researchers” have deduced that the Norse had witnessed the mighty North American primate in person.

However, the translation lacks authenticity. It ignores cultural expressions. The passage that described the natives of Newfoundland in reality said something closer to, “darker men, ill-looking, with bad hair.”

You read it correctly. The Norse were not describing Sasquatch, they were critiquing the natives’ bad hair. This is not surprising, considering the Norse cultural fixation on personal grooming (see Were the Vikings Dirty?).

It’s usually all fun and games, but what bothers me is that these shows are often interpreted as factual and mislead large portions of the population into believing complete malarky. My concern is that I may some day hear from someone, “hey, I heard on the History Channel that Leif Erikson mud wrestled with Sasquatch. Is that true?”

No, my poor, misinformed friend. It’s not. What you saw was as historically factual as Harry Potter.

Think of the power behind media. What other “facts” have we been force-fed that, in reality, are false? What will be the long term implications of this? In a democracy dependent on an educated electorate, it’s crucial that falsehoods are exposed and expunged.

That is why I believe that all shows about Bigfoot, UFO’s, and any other pseudo-scientific or cryptological subject should be prefaced by a disclaimer that tells viewers that it’s fiction, or at least not proven or accepted fact, and not endorsed by any credible academic body. Until then, I am going to boycott such programing. Sorry, Bobo.

If you’d like to read the sagas about Leif’s voyage to Newfoundland, here are a few links for you to explore:

June 11, 2015

Three Vikings Who Were More Interesting (and Notorious) Than Ragnar Lothbrok

Ragnar is a character from legend. There is no telling whether he was real or a fable. His recent ascension to fame in popular culture is without a doubt a good thing for Norse studies, but now it is time to take a look at those Vikings who we know for sure were real people and whose lives were in fact more remarkable than the legendary King of the History Channel.

1.Hastein

Supposed son of Ragnar Lothbrok—although he likely claimed this for prestige, similar to how the nobility in France all claimed lineage to Charlemagne—Hastein lived a life envied by his contemporaries. He began his journey as a relatively unknown warrior who appears in a few mentions beginning in the mid-9th century. His claim to fame was his voyage to the Mediterranean with his brother Bjorn Ironside, and together they sacked Cordoba on their way to the Mediterranean basin. Their fortunes were not consistent, however, and the islamic states of North Africa quickly mounted resistance to them. Most notoriously, Hastein helped to sack the city of Luna, which at the time they believed was Rome. They tricked the local clergy into believing that their leader had died of pestilence moments after converting to Christianity. The local clergy took pity on him and allowed the Northmen to enter the city to conduct a Christian burial. During the ceremony, Hastein sprang to life, murdered the bishop, and with his men sacked the city.

Hastein returned to his base on the French coast, an island now known as Noirmoutier, without most of his fleet which had been ambushed by the Moors at Gibraltar. Nevertheless, Hastein made a solid career out of raiding the Frankish Empire and earned the hearty reputation as The Scourge of the Somme and Loire.

Primary Source authors and documents which attest to Hastein’s life and notoriety:

Dudo of Saint Quentin

William of Jumièges

Annals of St-Bertin

Chronicle of Regino de Prüm

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

2. Leif Eriksson

Born to a father exiled from Iceland for being too violent, Leif undoubtedly lived a difficult childhood. The North Atlantic made for arduous subsistence, even for the Vikings. Due to his father’s reputation, he lived as an exile himself for the most part and did not attempt to make any significant return to Norway. Instead, he became an explorer, one of the most remembered to this day. Based on a rumor, he took ships across the seas in hopes of finding new fertile lands for his people. The rest is all very well known history.

Leif’s legacy helped to shape our view of the Vikings. He helped us to think of them as explorers rather than killers, as adventurers rather than rapists. Most importantly, he planted a seed in the consciousness of Europe, one which reignited in the 15th century and led Europe to global hegemony.

Primary source authors and documents which attest to Leif’s life:

Saga of Erik the Red

The Saga of the Greenlanders

3. Oleg of Novgorod

When discussing the Vikings, the Rus are often forgotten. It seems popular culture has had little trouble romanticizing the Norwegians and Danes who sailed West, but has classically held little interest in those who sailed East. But one of the most influential men of the early medieval period lived there, and his legacy lasted well into the modern era. Oleg began as a regent of the throne of Novgorod whose duty it was to oversee the training of the next monarch, Igor, son of Rurik of Novgorod (yet another fascinating character). During his reign, Oleg consolidated power among the the cities situated along the Dnieper river and eventually conquered the city of Kiev, which he then made his capital. Kiev was of strategic value as it was well placed to launch raids on Constantinople. Following several successful missions, the gentry of the city caved and struck a very favorable trade agreement with Kiev. This trade agreement helped to enrich the city under Oleg, and thrust the polities of Kiev and Novgorod into positions of power. Thus began the early history of the country we know today as Russia.

These are but three among a multitude of historical figures from Scandinavia who helped to shape the early political landscape of Europe, and who are, from a historical perspective, far more interesting than Ragnar Lothbrok.

Primary source authors and documents which attest to Oleg’s life:

The Russian Primary Chronicle

The Novgorod First Chronicle

The Kiev Chronicle (which really only deals with his death and burial)

Don’t forget, I wrote a couple of books. Feel free to buy one :)