C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 21

March 2, 2015

Author Update 3/2/15

My second novel has finally been released, and I must say I am much prouder of how it turned out than the first. I love my first novel, it was after all my first. But I feel I found my voice in my second novel, and I believe it will both engage and satisfy my fans, as well as new readers. On the heels of its release, I am continuing to synthesize the next installment of the Kindred of the Sea series, which will focus on Abriel’s eldest daughter Asa as she learns the nuances of leadership in a patriarchal world. The novel will again take readers to Ireland, but this time in more depth as the Vikings begin a major invasion. It will parallel an invasion of Brittany in the same period as the Carolingian Empire begins to lose cohesion. It will be fun to write, and hopefully to read.

A few announcements:

1. I am on track toward my goal to finish my first trilogy before the age of 30. In fact, since that date is three years away, I should be well into the second trilogy by then. My publisher certainly has no objections. For those who are wondering, the Kindred of the Sea series is planned out for six books, with the potential for 9 depending on the success of the second trilogy. I have all the research for the series finished, it is a matter of putting the stories onto paper.

2. At the request of my publisher, I am currently working on a new edition of The Line of His People, with a small amount of re-working, and another edit by my editor. I admit the first novel was rushed (I wanted it published before beginning the school year of 2013-2014 as a teacher), so we will be making a few improvements in the near future. I do not have a firm date for when this will happen, but we are working on it right now.

3. My blog is narrowing in on 100k views, WHOA! I did not expect to each that number in such a short time! Thanks to everyone who has stopped by.

I thank all of my fans around the world and hope you enjoy my second novel! Leave me a review if you can, thanks! And remember, these books are written at the Young Adult level, so if you have children, nieces and nephews, or grandchildren, feel free to share Abriel’s story with them.

Sincerely,

~C.J. Adrien

February 25, 2015

The Truth About Viking Armor: No Horns, No Uniformity Either.

10th Century Chieftain

While the History Channel would have us believe they were a leather-clad biker gang akin to the Sons of Anarchy, the real Vikings would have had a much more diverse wardrobe. It is first important to understand that the Viking Age lasted almost three centuries, during which styles and clothing changed. Early raids in the 8th century were carried out by small groups of free warriors, banded together for the purpose of pillaging and acquiring wealth to take home. One hundred years later, the West came under siege as ambitious warlords repurposed their warriors for invasion requiring a refitting of their battle gear to withstand the test of large confrontations. This begs the question: what did they really wear?

Early on during the Viking Age, the warriors of various raiding parties would have worn what they could afford, as well as what worked at sea. Anyone who has worn leather knows that salt water is incredibly corrosive to it, making it tough and unwearable. Therefore leather would have been sparse. A more common type of clothing for the era was cloth: heavy interweaved fabric designed to absorb slashing blows (but not stabs). Cloth would have kept sailors warmer at sea as well, and anyone who has ever sailed knows how cold the ocean’s winds can be, even on a hot, sunny day. Cloth unfortunately does not leave much behind for us to find or add to the archeological record. We may only deduce that it was the clothing of choice because of availability, and because of the universal use of cloth protection across the western world at the time.

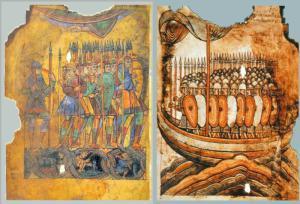

Later in the Viking Age the Vikings diversified their wardrobes. The riches they brought home from raids increased the wealth of the average free warrior, allowing him to invest in heavier pieces of equipment. Wealth was not the only import to Scandinavia either. Vikings brought home new technologies for farming and building, as well as weapon making. Does this mean they all began to wear mail and steel helmets? Perhaps not, but there is evidence to suggest that some armies at least may have done just that: equip everyone with the best armor money could buy. Below is a depiction of a 10th century attack on Guérande in which the Vikings (in a ship on the right) are all equipped with shield, helmet, hauberk, and lance. (click to enlarge)

The above drawing is of the 10th Century invasion of Brittany, which led to a 20 year occupation of the region, including the cities of Rennes and Nantes. In fact, the Breton leaders who expelled the Vikings only did so after they had craftily turned the Normans in Normandy against the Normans in Brittany. What this evidence tells us is that the Vikings repurposed their armies to suit their ambitions. Early raiders could not stand up to the better equipped Frankish armies of Charlemagne and Louis I, but as they increased their wealth and shifted their ambitions, they became better equipped and more organized. Depending on the region they attacked, the Vikings adapted to their enemy and adopted forms of arms and armor influenced by those who they fought. For example, on the island of Groix in southern Brittany a Norman burial dating to the mid-10th Century yielded twenty-four shields of a unique design which historians suppose were built by the occupying army. It is demonstrative of the willingness of the Northmen to improve their equipment, and also shows us that their equipment would have been diverse across the world.

So what did they really wear? The answer is that they wore what suited them for the time and place. In the West, they began to resemble their British, Breton, and Frankish neighbors. In the East, they began to resemble the Byzantines and the Slavs they occupied. Uniformity was not their strong suit, and this was perhaps their secret to success: adaptability. There is a great deal of conjecture and interpretation in dealing with what the Vikings wore, and there is still a great deal that we do not know. We do know that as the Viking Age progressed, the attire became more region-specific. A viking in Brittany in the 9th Century would have appeared different from a Varangian in Constantinople in the 10th Century. The only universal piece they all wore was a beard; it was cultural and several sources mention how shameful it was if a free warrior could not grow one.

Sponsored Ad

February 24, 2015

The Curious Case of al-Ghazal

In the 9th Century a Moorish ambassador named al-Ghazal set sail for foreign lands to study a people called the Majus. His account tells of his voyage across the ocean to a splendid island described as having lush, flowering plants and abundant streams leading to the ocean. For years historians struggled to gather consensus on who these Majus may have been, but more recently it has become accepted that they were indeed the Vikings. Unfortunately, the consensus ends there. Some scholars believe the embassy of al-Ghazal to have taken place in Denmark, whereas others propose he had visited the court of Turgeis, a powerful warlord who ruled over much of Ireland. His account is compelling and offers a tremendous volume of information about the Majus many scholars believe no chronicler of the time could have fabricated.

The source for al-Ghazal’s embassy to Ireland is a document produced by Abu-l-Kattab-Umar-ibn-al-Hasan-ibn-Dihya, who was born in Valencia in Andalucia, about 1159 A.D. The facts and anecdotes in the story were derived from Tammam-ibn-Alqama, vizier under three consecutive amirs in Andalucia during the ninth century who died in 896. Tammam-ibn-Alqama had allegedly learned the details directly from al-Ghazal and his companions. The only manuscript of ibn-Dihya’s work was acquired by the British Museum in 1866. It is titled Al-mutrib min ashar ahli’l Maghrib, which translates to An amusing book from poetical works of the Maghreb.

The entire account is quite possibly true, and quite possibly accurate, but the subject remains debated. Nevertheless, it appears the Moors took an interest to the Vikings, no doubt a result of their early interactions with Viking explorers and tradesmen. If true, this account demonstrates yet another interaction between the Vikings and the Muslim world previously unknown to us, and is telling of the openness of Norse culture to visitors. In the account, al-Ghazal spends a great deal of time with the wife of the king of the settlement who he takes a strong liking to. The document is compelling evidence that a Muslim visited Ireland in the 9th Century and, according to his account, got very cozy with the king’s wife during his stay.

Source:

Allen, W.E.D. The Poet and the Spae-Wife. Titus Wilson and Son, Ltd. London, 1960.

Sponsored Ad

February 20, 2015

Vikings Season 3: Where Are All Their Helmets?

Ragnar and company were at it again in the first episode of Season 3, and the producers did well to throw us all back into the thick of battle. It was entertaining, and the actors left us with the impression that there is more to the story than meets the eye.

Yet I am left wondering why the Vikings were given such a light wardrobe compared to their admittedly much better equipped foe. Particularly, where are all their helmets? We know they wore them, and we know helmets were a rather central piece of armor warriors typically did not do without. What did a Viking’s helmet look like? It turns out, they varied widely among the Norsemen who designed their helmets with influences from the places they traveled. For example, the Rus’ (Swedish Vikings) wore more pointed helmets with an Eastern flare, influenced by the Byzantines and other peoples they encountered in the East. In the West, they wore more conical helmets much more closely related to the helmets the Carolingians wore. Pictured below is an example of a helmet found in Norway, one of the rare examples ever found.

Why then did the History Channel decide to omit helmets from their representation of the Vikings? Who made that call? In their defense, helmets are one of the rarest forms of armor found in archeological digs, meaning they perhaps were not universal. This could be the reason the producers decided to forgo giving Ragnar the famous “dragon head” look with a low-swooping visor and conical helmet. It is not wrong to suppose that the average free warrior may not have had the resources to afford the more expensive forms of armor such as a mail hauberk, steel greaves, or a helmet. It is not necessarily correct either. What we do know about the proliferation of steel armor is that by the Norman conquest of England in 1066 they all wore conical helmets and an array of mail and leather armor. We unfortunately do not have any visual depictions of warriors from that time except for the Bayeux Tapestry, so it is difficult to say with any certainty whether or not the Vikings commonly wore helmets, or when such a trend may have begun. Therefore, it is up to interpretation.

In my opinion, they all would have worn head gear of some sort. A warrior culture as developed and seasoned as the Viking Age Scandinavians would not have been so foolhardy as to believe themselves exempt from the dangers of initiating battle without proper attire. Perhaps helmets are difficult to find because they were more commonly made of leather, a proposed theory to the absence of helmets in the archeological record. I am also of the opinion that mail hauberks were much more common than previously though among the Vikings because they were readily produced in the Carolingian Empire, a frequent target of raids. Mail was also produced readily in the wealthy Byzantine Empire, which meant the Rus’ would have had access to such armor as well. Pictured below is what many (if not most) believe to be a more accurate wardrobe for a Viking warrior. Keep in mind, the figure below represents what would have been a wealthier warrior, perhaps a chieftain or Jarl.

Should we be concerned about the lack of headwear? Anyone who has had any experience in contact sports or combat or otherwise knows that the head is the first and most important part of the body to protect. Ancient peoples knew this as well. The Romans knew this, the Carolingians knew this, the Ancient Egyptians and Assyrians knew this. Helmets were not a new thing. I believe the Vikings would have known better as well. I am careful to say that this is my opinion because, as I mentioned above, helmets are still an incredibly rare find among Viking Age artifacts, which may mean the History Channel has it right. I am open to the possibility that my conclusion is wrong—as all historians should be. Nevertheless, a Viking battle would likely have looked more like this:

Or perhaps the choice to omit helmets in the show was made after a fight between the wardrobe department and the hair stylists. After all, we wouldn’t want Rollo’s beautiful hair to be smushed under a helmet, would we?

Sponsored Ad

February 19, 2015

The #1 Thing History’s Vikings Got Right

To the history buffs who believe the show Vikings on History Channel to be an insult to the true peoples of Viking Age Scandinavia: relax. Yes, the show is a blunder in several key areas of history, particularly concerning the clothing they wear and much of the clothing their opponents wear (I am referring specifically to the ill-placed Conquistador helmets of the soldiers in Northumbria). And yes, the teasers in which Ragnar is supposedly going to attack Paris—an event we know to have taken place in 845 A.D.—is completely nonsensical since the show already placed him at Lindisfarne—an event which we know to have taken place in 793 A.D. Perhaps Ragnar is secretly an immortal Elf from Elfheim, because the show is implying he is going to be in his 70’s or 80’s in season 3 which no new haircut can accurately portray. But here is why none of it matters: the one thing History Channel did right was to make sure the show was regarded as fiction.

The first thing you may notice when reading up on the history of the Vikings is that the legendary hero Ragnar Lodbrok (hairy breaches) is not actually represented in the show. Vikings’ protagonist is Ragnar Lothbrok, a similar sounding name, but not quite right. The producers made this distinction because as it turns out much of what we know about the Viking Age is highly subjective and up for interpretation. The Sagas from which Ragnar’s story is extracted are bit like the Christian Bible—they are a collection of stories perhaps written about real people, but written decades and even centuries after the fact. This makes the sagas a poor source of information about the events of the Viking Age, but they are a wonderful insight into storytelling and culture. Therefore, Ragnar Lodbrok remains what historians refer to as a “legendary king.” In other words, there is no reliable, definitive proof to say that he actually existed. Ragnar is not alone. There are dozens of legendary figures whose true identity is up for debate. The producers of Vikings have thus created a fictional character based on a legendary figure, meaning they had no intention of sticking to a strict, history-based timeline from the start.

With all of this in mind, it is important for history buffs, Viking Age historians, and other connoisseurs of the Vikings to ignore the historical relevance of anything brought up in the show. They’re not trying to get it right. The series is doing exactly what it was intended to do. For the producers, it is generating interest in a specific field of history. To the studios, it’s making money. For the audience, it is a captivating drama with plenty of action to satisfy our base desires. My recommendation is to watch, enjoy, discuss, and have fun. If historical accuracy is what you’re looking for, try a book. Historical Fiction authors are much more obliged to stay within the rigid confines of history because their audience is generally more cultivated and likely to catch them on an error. Plus, a book leaves much more up to the imagination, so the Vikings you read about are going to be much more accurately represented in your mind than those you see on TV.

Sponsored Ad

February 17, 2015

3 Places You May Not Know the Vikings Visited

When we think of the Viking Age, we think of the invasions of England and Ireland, of the exploration of the Eastern Steppes, and of the attacks along the coasts of Western Europe. Recently, historians have expanded this view through discoveries which have expanded what we know about the breadth of influence the Vikings had across the world. You may know that the Vikings visited Spain, and even sacked Seville in the 9th Century. You may also know that they venture far enough East to end up in Constantinople where they were hired as mercenary fighters. What you may not know are some of the other less known places the Vikings visited such as Sicily, Morocco, and even Baghdad.

Sicily

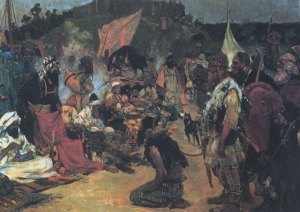

The Vikings’ visit to the Italian Peninsula was short lived. We know from several sources that one particular expedition initiated the Norse exploration of the Mediterranean Basin, the first of several. A man named Hastein, a supposed son of Ragnar Lodbrok, set out in the 850’s A.D. with thirty ships to sail around Iberia, through the straight of Gibraltar, and into the Mediterranean. This first expedition was not considered all that successful. Although they sacked Seville and made away with plenty of plunder, their fleet was ambushed in the Mediterranean by the a Muslim navy which made quick work of them. Hastein is believed to have narrowly escaped the attack with half a dozen ships and dumped most of their plunder to be able to outrun their attackers. They may have ventured as far as Italy, but the account is vague so we are not entirely sure. However, the report Hastein brought back to the North inspired others to attempt to raid the Mediterranean whose coastal settlements were thought to be wealthy. As early as 999 A.D. a more aggressive invasion began in Sicily led by Norman Brigands (Vikings from Normandy) returning from pilgrimage who found the island to be an attractive target for invasion. They began what would become the Norman Invasion of Sicily. After a long but successful campaign the Normans conquered Sicily and established the Norman Kingdom of Sicily which remained under their control well into the 13th Century. In fact, William the Conqueror’s descendant Henry II, known as the father of the Angevin Dynasty in England, maintained heavy influence over Sicily, which his son Richard the Lionheart used to launch his crusade in the Middle East.

Morocco (Berbery)

Hastein’s expedition also attempted to attack Muslim settlements in North Africa. It is this attack which historians believe allowed the Muslims to gather their navy to confront the Norse raiders as they entered the Mediterranean. While they left little trace of their time in North Africa, their sudden appearance alerted the rest of the Islamic world to their threat. Word of their bold and hostile actions are believed to have reached as far as the ruler of Constantinople. While not a singularly important event, the mystique it would have created around the Norsemen may have helped to further their reputation in the Muslim and East Christian world.

Baghdad

The Rus, a tribe of Swedish Vikings who travelled East along the Dnieper and Volga rivers, established extensive trade routes which reached as far as Baghdad. Their trade took them through Constantinople and into the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as through the Caspian and Black Seas, even through the kingdom of the Kazhars whose lands included the modern day country of Georgia. We know they must have travelled as far as Baghdad from several sources, including sources left by the Byzantines, the Muslims in Baghdad, as well as archeological finds in Russia and Scandinavia in which there have been coins and other trade goods produced specifically in Baghdad. What did the Rus trade with the Muslims? They offered one of the most luxurious types of good: furs.

Sponsored Ad

February 10, 2015

The Vikings: Noble Savages, or Not?

Recent scholarship has done much to rescind many of the old paradigms of Norse history, particularly when it comes to their culture and the ideal of the Noble Savage. Historians and archeologists have created a new image of Viking Age Scandinavians, one in which they are clean, civilized, and honorable to a fault. But is this new view of these historical people accurate? Or has the pendulum of our cultural lens swung too far in the opposite direction? The answer is not simple, but there are a few things to consider before we radically change how we view the Vikings and their culture.

First, the word ‘Viking’ has evolved into a word most people use porously to refer to Viking Age Scandinavia as a whole, but the original intention of the word as used by early historians of the 19th Century was to designate a specific portion of the population: those who sailed away from home. The word ‘Viking’ is derived from the Norse word ‘Vikingr’ which translates loosely to sea rover or pirate. Viking Age Scandinavians did not often use this word, nor did they use it to describe themselves. Therefore it is important to make the distinction between those Scandinavians who stayed and those who left because they were generally entirely different people. Those who left we should call Vikings, and those who stayed we should call Scandinavians. With this distinction clear, we can now analyze each population individually to see if the ideal of the Noble Savage applies or not.

In general, the sedentary populations of Scandinavia were not noble savages. They were, in fact, nearly identical to their Northern Germanic counterparts the Saxons and the Angles, except for minor linguistic an cultural differences. From a religious standpoint, they derived their pantheon from the same germanic construct of their neighbors, and their warrior cultures drew many parallels. They were different however insofar as the Scandinavians lived much more on the waters of the Baltic. Particularly true for Norway, settlements only had contact with one another through sea trade because the mountainous terrain between them was much more difficult to travel. It is because of this difference over their northern Germanic cousins that led to their more developed seafaring culture. The scandinavians had extensive fishing fleets, complex agriculture, animal husbandry, and they were not in any way nomadic except for the expansion of settlements across the Northern territories. They were certainly not savages as the Christians deemed them at the time. In fact, their society was in many ways more advanced than their Christian counterparts whose only real advantage was a well developed written language. That is not to say Scandinavians at the time did not write—runes are evidence of a complex written system, but how prolific or universal it was across the populations of the time is still unknown. In any case, the Scandinavians of the Viking Age were not the noble savages they were depicted as in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Vikings, or Sea Rovers, left the North in search of new lands in a massive exodus that endured nearly three centuries. Initially, the lands they visited were lands they explored to trade. It was not until Christendom barred trade with non-Christians that these voyages turned violent. Due to the harsher weather conditions of Scandinavia, and particularly due to the short growing season, Scandinavians slowly became reliant on trade with the south to sustain their population. With this trade removed, they were forced to seek out what they needed by force. Raids began in Frisia, immediately south of Denmark, and expanded from there. What made the Vikings different from their Scandinavian homes was that they valued their warrior culture above all as it was necessary to carry out their new missions in foreign lands. The warrior culture was not new, but it certainly expanded and changed over the course of the 9th and 10th Centuries. Due to this, the depiction of them by the Christians they attacked resembled the ideal of the Noble Savage much more than the Scandinavians who remained up north. But, this does not mean that they were noble savages. Where they travelled they learned new skills, spread their own culture, and eventually integrated into the societies they had previously sought to conquer. One prominent example of this is Normandy where Vikings signed an agreement with the king Charles the Bald who granted them land rights. Those Vikings who settled Normandy christianized and developed a new advanced culture who would become the best example of western civilization of its time. The Vikings did more to ‘civilize’ Christendom than Christendom did to ‘civilize’ the Vikings. Therefore, the ideal of the Noble Savage when applied to the Vikings is totally wrong.

Has the pendulum swung too far in the other direction? No, it arguably has not swung far enough. Too often the Vikings are seen as a force of destruction in their world when in fact they were no more violent or vicious than any other cultures of the time. It was an age of violence. The last ten years have seen tremendous advances in our knowledge of the people we know today as the Vikings, and that knowledge is expanded upon every day. We are seeing the emergence of a much more complex and advanced civilization than previously thought, one which was nearly wiped out after the Christians converted Scandinavia. Only now with new discoveries and advances in technology are we discovering the true identity of the Vikings.

Sponsored Ad

January 27, 2015

The Vikings in…Georgia?

No, the Vikings did not venture as far as the southern state of Georgia in the United States. Georgia in this case refers to the country of Georgia on the coast of the Black Sea wedged between the countries of Russia and Azerbaijan. Still, when one thinks of this small country and its history, the Vikings are not the first historical people to come to mind. Nevertheless the Vikings had a great deal to do with the development of the nation-state that would become Georgia, as well as the political landscape of the entire Eastern Caucasus region, including the Caspian Sea.

Varangian trade routes Circa 9th Century. Click to expand.

As early as the mid 9th Century, Viking explorers known as the Varangians (also known as the Rus’) sailed up the Volga and Dnieper rivers toward the East. They established numerous trade routes from Sweden to Byzantium (Turkey), and even to the Caliphates in the Middle East. One of their trade routes took them directly through lands situated in modern day Georgia. At first these foreign explorers were well received for their lucrative trade goods, but this did not last long. The ambitious leaders of the Rus’ who required fame in battle and large amounts of wealth to maintain legitimacy to their leadership and titles began to plunder the lands of the Slavs, the Khazars, and the Byzantines. Georgia at this time was occupied by the large and influential empire of the Khazars who had classically maintained dodgy relations with the Byzantines. The arrival of the Rus’ initially unified the rulers of these empires to repel them, but the early successes of the Northmen forced a wedge between their diplomatic relations, creating new conflicts which allowed the Rus’ to sail unabated through their lands. Because the Rus’ were so successful in raiding and plundering the lands of the Khazars, the empire began to lose integrity. Small kingdoms under their dominion began to rise up out of fear that their overlords were powerless to stop the Rus’.

Khazar Empire up to 850 A.D. Click to expand.

To abate this loss of control, the leaders of the Khazars fragmented their empire and placed friendly monarchs on the thrones of each territory. Thus, in 888 A.D. as the Vikings were sacking the capitals of Europe, a new monarchy emerged in Georgia: the Bagrationi Dynasty. The politically fragmented empire of the Khazars then came under attack from other nomadic peoples from the East. The combined pressures of both fronts, against the Rus’ and the Seljiuk tribes, caused a complete collapse by the 11th Century. Once the empire of the Khazars collapsed, the Bagrationi dynasty was able to maintain autonomy from the Byzantines as well as the Seljiuk tribes for two centuries in what is considered a “Golden Age” for Georgia. Unfortunately, a new menace led to their demise. The Mongol invasions in the early 13th Century saw the obliteration of the kingdom.

What does this all mean? How can all this information be digested into an easy-to-explain dinner party blurb? Georgia owes its existence to the Vikings. That’s a bold statement, and a complex one to support in any academic discourse. But, it is a safe one to use because in fact the Vikings created the conditions which allowed the historic monarchy of Georgia to be restored when it was well on its way to being snuffed out of history. The Khazars were content in allowing the Bagrationi dynasty to disappear, but the Rus’ ensured their survival by destabilizing the empire. They reestablished monarchy flourished for two hundred years, allowing the people of the kingdom to develop their own sense of identity, language, and culture free from the influences of a dominating (and predominantly Muslim) empire.

Sources:

Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh (1980). Burke’s Royal Families of the World: Volume II Africa & the Middle East.

Moss, Walter (2002). A History of Russia: To 1917. Anthem Russian and Slavonic studies. Anthem Press.

Noonan, Thomas S. (1999). European Russia c500-c1050. The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024. Cambridge University Press.

Shepard, Jonathan (2006). Closer Encounters with the Byzantine World: The Rus at the Straits of Kerch. Cambridge University Press.

Verlag, Otto Harrassowitz. Pre-modern Russia and its world: Essays in Honour of Thomas S. Noonan. Cambridge University Press.

Sponsored Ad

January 21, 2015

5 Questions Viking History Experts Hear Every Day (and answer).

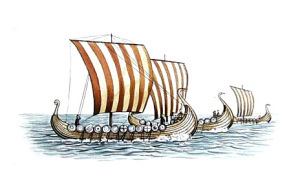

Vikings are cool. We can all admit it. They sailed on ships with dragon heads and terrorized villages and monasteries for two centuries, and are revered as fearsome warriors characterized as “Noble Savages.” Because of their popularity, folks always seem curious and full of questions when they meet someone who knows a great deal about them. The following are five questions Vikings History experts hear without fail at every dinner party they ever attend.

1. Why did the Vikings wear horns?

They didn’t. The horns on the helmet are an invention of a 19th century costume designer named Carl Doepler who wanted his “Vikings” to appear more barbaric during the 1876 Berlin staging of Richard Wagner’s opera The Ring of the Nibelung (the most famous song being Flight of the Valkyries). Unfortunately, the horns stuck, and here we are today answering this question.

2. Did the Vikings call themselves Vikings?

No. The word “Viking” is a derivation of the old Norse word “Vikingr” which literally means “Sea-Rover.” It was used during the 19th century by historians to describe the Scandinavian raiders of the early medieval period, but of course once it got out into the general public the word came to signify all Scandinavian peoples of that era. In reality, the Vikings would have called themselves after their home region. For example, the Annales D’Angoulême mention a group who attacked Nantes in 843 C.E. as referring to themselves as Vestfaldingi, or Men of Vestfold (a region in Norway).

3. What made them so cruel?

They lived in an age of violence. The Christians they attacked were no more peaceful than they. In fact, it was not uncommon for high ranking church officials to hire mercenary armies to attack noblemen who owed them money (which was often the case). Charlemagne, the most powerful ruler of the Christian world at the outset of the Viking Age, was notorious for massacring non-Chritians mercilessly. There is even a case where he captured some 3000 pagan Saxons and forcibly baptized them in the Elbe river where he ordered his men to drown them. The Vikings were not the only raiders of this time either. In the East, the Slavs frequently raided the land of Louis the German, and in the West the Bretons frequently raided across the Breton March in Brittany. So in reality, they were no more cruel than those they attacked.

4. Weren’t the Vikings really dirty?

Contrary to popular belief, the Vikings were cleaner than their Christian counterparts. The Middle Ages got its stinky reputation from the fact that Christianity viewed bathing as a sign of vanity, and therefore sin. There is a great quote from a French monk who said, “the more pious we are, the more we stink.” Before the Christianization of Scandinavia, it was culturally dictated that one should bathe at least once per week. Archeological finds have revealed a wealth of grooming items as well, which have indicated that the Vikings took personal hygiene and grooming very seriously. So in reality, the Vikings were clean, whereas the people they attacked stunk. Perhaps this explains why they slaughtered priests so easily–they thought they were infected with a pestilence.

5. Who is you favorite Viking god?

My favorite NORSE DEITY is Freyir, god of the hunt, war, and sex. He liked to eat meat, whoop ass, and romp. That’s my kind of guy. And he was very popular during the Viking Age for the same reason. He is often depicted as a statue with an erect phallus, which is both symbolic of how he was viewed by the Vikings, and good for a laugh among historians.

Personally, I am overjoyed that there is a renewed interest in the Vikings and I do not mind answering any questions about them in the least. I hope other Viking History experts feel the same. We have learned more about the Vikings in the last 20 years of research than in the previous two centuries of studies combined, and the discoveries are only increasing. It is an exciting field of history to be in, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Sponsored Ad

January 18, 2015

Viking Berserkers: Fact vs Fiction

You have raised your shield and interlocked with your friends. From behind it you peer across the battlefield on a cold, foggy day looking for the enemy. From the unseen depths of the mist you hear the howls of enraged men, driven mad before battle. Then you see them. A horde of bellicose warriors in wolf’s clothing charging with little armor and large two handed weapons aimed at your head. In fear you cower behind your shield with the hopes the shield wall holds in the face of this frightful enemy. You are a Saxon warrior who has mustered at your king’s command to fight, but the aggression of the Northman Berserkers was too great. The stories of their resistance to fire and imperviousness to sharpened blades has made you tremble like a leaf. To save your own skin, you break and run as the limbs and heads of your allies are cleaved in the whirlwind of the enemy’s charge.

Fact or Fiction: Did the Berserkers really exist?

Fact. Berserkers, their name named derived from the Old Norse for “wearing of bear clothing,” would have been a frightful spectacle, if everything said about them in the sagas is to be believed. Outside of the many sagas in which they appear, they are seldom mentioned by Christian sources, except in the case of Harald Fairhair who used them as shock troops during battle. There is enough textual evidence to conclude that an elite force of warriors known as Berserkers did in fact exist and helped to shape the geo-political landscape of their day.

Fact or Fiction: Berserkers ingested drugs to induce their psychotic state.

Fiction. While there is a theory that they may have consumed psychedelic mushrooms to induce their transformation of behavior, the only mushrooms available to them with such properties would have been lethal in the doses required to “go berserk.” Instead, it is more widely accepted that Berserkers consumed copious amounts of alcohol and participated in a semi-religious ritual to evoke the mental transformation of the warriors into a state of hyperarousal.

Fact or Fiction: Berserkers wore wolf skins into battle.

Fact. Most attestations make mention of their wolf or bear skin clothing which was used during their ritual preparation for battle as the symbol for their transformation. It is surmised that they sought to become the animal which they wore to take on its beastly aggression. The skin would have also been an unusual form of battle regalia, and would have lent to their intimidating appearance. Berserkers would have relied heavily on their reputation to instill fear in their enemy, a kind of psychological warfare often used in antiquity.

Fact of Fiction: Berserkers were impervious to fire and edged weapons.

Fiction. While their frenzied state may have been truthful, the practical application of the name Berserker would have been used in most contexts as a means to deter an enemy or to describe their own ferocity. Although attestations describe them as having the ability to devour hot coals and chew through iron shields, it is not likely they would have truly possessed such powers.

Despite much of their reputation being embellished and exaggerated, the Berserkers were fearsome warriors in their day. Their rituals made them transform into ravenous beasts capable of causing significant damage to their enemy. We do not know exactly how this would have looked, especially since the sagas tend to be magical in their descriptions of them, but we do know for sure that they existed, that they scared the living daylight out of their enemy, and that they were used precisely because of their prowess by certain monarchs. So dangerous were they that the Jarl Eirik Hakonarson of Norway outlawed them in 1015 for fear that they might lose their minds and turn on their leaders.

Sponsored Ad