C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 24

July 29, 2014

The Viking Connection

By 847 C.E. it became clear that the Viking invaders of Ireland had developed political ambitions beyond the sporadic raiding of the previous three decades. Within one year the Irish won an unprecedented four victories over the Vikings which effectively expelled a tremendous portion of the invaders from Ireland (Graham-Campbell, 1989). That same year in Brittany Viking raiders began an invasion of the mainland peninsula and won three decisive victories over the Bretons (Cassard, 1996). Current scholarship makes no connection between the events in Brittany and Ireland in 847 C.E., but evidence exists to link these events more closely than previously acknowledged. It begins in 799 C.E. with a raid on the island of Noirmoutier found south of the mouth of the Loire River. The monks from the monastery of Saint Philbert fled the island, but returned the following year. In 834 C.E., the monks abandoned the island definitively due to the persistence of the summer raids by Vikings (Delhommeau, 1999). This allowed the Vikings to use the island as a base beginning in 837 C.E. from which they could raid the Loire River Valley. If we consider the larger scope of events in 9th century Europe, Noirmoutier appears to be a rather small and insignificant chapter in the Viking Age. However, the resources of the island (salt), and by extension of the region of Brittany, attracted repeated raids and invasion attempts. Salt was after all a necessary resource for any army of the time, and the Vikings were no exception.

When the Bretons under the command of Barbe-Torte retook the city of Nantes in the 10th century, they found a derelict city which should have been a flourishing trade center. This is indicative that the Vikings had no long term settlement ambitions in Brittany, and that their assets in the region were for purely military reasons (Price, 1989). Specifically, the Vikings held parts of Brittany and Noirmoutier for the acquisition of two important resources: salt and wine. Both are needed in war; and the ambitious warlord Turgeis necessitated all the help he could muster to see through his plans to conquer Ireland. The need for resources, and the lack of permanent interest in Brittany point to an important connection between the Vikings in France and Ireland who may have supported one another during military campaigns to ensure their mutual interests.

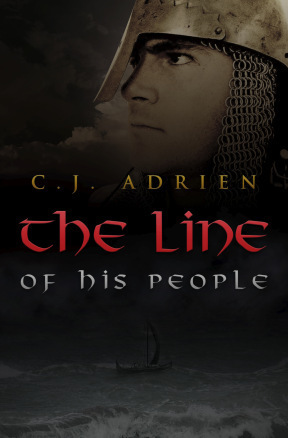

C.J. Adrien’s second novel — titled In The Raven’s Wake and due to be released in 2015 — will make use of exclusive research done on the connection between the Vikings of Ireland and Brittany. The protagonist of Adrien’s debut novel The Line of His People will be swept out to sea to Ireland where he will again fight to survive in one of the most violent periods of European history. Haven’t read the first novel? Get it HERE for $0.99.

Bibliography:

Cassard, Jean-Christophe. Le Siècle Des Vikings En Bretagne. Paris: Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot, 1996.

D’Haenens, Albert. Les Invasions Normandes, une Catastrophe?. Paris, 1970.

Delhommeau, Louis. Ermentaire: Vie et Miracles de Saint Philbert. District de L’isle de Noirmoutier, 1999.

Graham-Campbell, J. The Viking World, (rev. ed.). London, 1989.

Hall, R. A. Viking Age Archeology in Britain and Ireland. Princes Risborough, 1990.

Price, Neil S. The Vikings in Brittany. London: Viking Society For Northern Research, University College London, 1989.

Smyth, A.P. Scandinavian York and Dublin, (2 Vols.). Dublin, 1975-79.

VIKINGS novel “The Line of His People” for $0.99 on Kindle

Join the adventure that has reached #1 in Norse Historical Fiction in the UK Kindle store!

Buy now on Kindle USA.

Buy now on Kindle UK.

July 23, 2014

Progress on “In The Raven’s Wake”

As promised, I must inform you, my much loved readers, about my progress on the sequel to The Line of His People which has tentatively been named In the Raven’s Wake. As the outline and character chart stand, the novel will likely become a 110,000 word behemoth with enough action and battles to make Tolkien George R.R. Martin squirm. Again the Vikings will be pitted against Christendom and the protagonist, Abriel, will find himself caught between the two worlds. The villains of the sequel will make the ignominious Adalard of Corbie look like a saint (although Adalard will make a small appearance). Writing this sequel is even more fun than the first. In my mind the story has taken a life of its own, yet is steeped in vigorously researched history.

All of your favorite characters — Abriel, Kenna, Oddr, and Gael the priest — have returned and will be joined by a few more central characters among their inner Circle. Ulfr, a warrior Abriel rescued in Iberia, has become a close friend and confidant to the king of Herius. Cnut, a malformed man who survived the trials of childhood to become a warrior in his own right, has joined the ranks of the Vikings. On the horizon, however, the peaceful settlement on Herius will be challenged for their right to exist. Other Northmen will descend upon the island in search for land and loot.

The most exciting setting for the novel will be the northern coast of Ireland. I do not want to spoil the story more than I have to, therefore I will not elaborate on why or how or who will be in Ireland, but Northern Ireland will be a prominent setting.

Stay tuned for more author updates as the writing comes along. I hope to have the novel finished and ready for retail (and a free giveaway) by Christmas.

From Bend, Oregon, I bid you all a wonderful continuation!

July 19, 2014

Invitation of the Rus: A Long Forgotten Common Heritage.

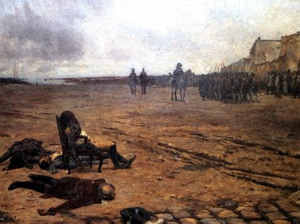

Above is a painting of one of the defining events in European history. During the exploration of the eastern steppes in the 9th Century, Swedish Norsemen discovered a variety of slavic settlements rife with conflict and discord. This constant strife between tribes allowed the Swedes, then known as the Rus (or Varangians), to play local politics. According to the Primary, the Slavs quickly recognized the leadership qualities of the Rus and their potential to help unite the warring Slavic tribes. Thus, as pictured above, the Slavs extended a formal invitation to the Rus to become their governing leaders. In Russian history, this moment is considered the genesis of their autocratic past under the Tsars, and the invitation is considered to have been an act of appreciation on behalf of the Slavs. In more revisionist circles, the invitation of the Rus was more likely the product of a lengthy battering of the Slavic tribes by Swedish raiders who relentlessly pillaged and enslaved the people of ancient Russia. It is therefore recognized that the invitation of the Rus was an act of preservation, with the prevalent idea that if the Slavs had Swedish leadership, they might be spared the devastation of the Swedish raids. That supposition has proved true, as the invitation of the Rus sparked a societal reorganization that saw the creation of powerful city states such as Kiev and Novgorod, the predecessors of the Muscovy (today’s Russians). What I draw from this short piece of history is the common heritage shared by the people of modern Russia, Ukraine, Belrus, among others. The intermingling of the people of the region spans back a millennia, but in the end they all originate from the same magnanimous event which propelled their society towards progress: the invitation of the Rus. It is a shame this commonality is not recognized today when the escalating conflict in Ukraine is approaching the status of the next powered keg of the world, a threat which concerns us all.

July 11, 2014

Le Passage du Gois

C.J. Adrien appearing to part the ocean. In reality, he is standing at the parting of the sea over Le Passage du Gois as the tide begins to recede to uncover the road.

Le Passage du Gois is a regularly flooded road which connects the island of Noirmoutier to mainland France. The name ‘Gois’ dates back to the 16th century and is derived from the Old French verb ‘Goiser’, which literally meant ‘to walk while wetting one’s clogs’. It is surmised that the passage earned the name from travelers who attempted to cross a sand bar revealed at low tide between the island and the mainland. Over the centuries, several construction projects have taken place to stabilize the passage and prevent both the further accumulation and the erosion of the sand bar to allow those who could not afford a ferry to the island to cross. A cobblestone road was eventually completed in 1840 to allow horses and carriages to cross at lesser risk.

As the tide rises to cover the road, the water can move as fast as a galloping horse. Anyone or anything caught in the waters is swept away to sea. It is considered a perilous crossing, and tourists must pay close attention to the tides to avoid personal injury, or death. Despite this, Le Passage du Gois is a world famous tourist destination, and the rising tide is a popular attraction for the island of Noirmoutier.

In 1999, the Tour de France crossed Le Gois in the second stage. The peloton suffered a major accident, and several cyclists favored to win the Tour were left seven minutes behind the breakaways. Alex Zulle, for example, finished the tour in second place behind Lance Armstrong with an overall time just under seven minutes. It is often thought that had the accident not occurred on Le Gois, Lance Armstrong would not have finished first. In 2005, the Tour de France again crossed Le Gois, but this time during the first stage time trial. Cyclists crossed Le Gois one at a time, thereby avoiding the calamity of 1999. Author C.J. Adrien (pictured above) had the privilege of being invited to the starting village where he met and interacted with several cyclists, and rode in a support car behind one of the cyclists for the length of time trial course. Unfortunately, Lance Armstrong was not available for C.J. Adrien to meet (even though all the other cyclists were, including Jan Ulrich), much to the author’s chagrin.

Le Passage du Gois remains one of C.J. Adrien’s favorite places in the world.

July 9, 2014

Huge New Discovery!

If you love Vikings, you MUST read THIS! A new discovery in Ireland is about to have tremendous implications for Viking history. This is a MUST FOLLOW story!!! Click the photo to read the article.

July 8, 2014

Great Twitter Find

July 7, 2014

The Vikings in Bretagne

A remnant of the Viking Age: depicted are the Vikings in Guérande.

A skaldic verse from Egill Skallagrimson paints the picture of what once was considered the perfect Viking; created impatient from birth, presumptuous, and with a burning desire for a far-off adventure:

“My mother promised me, and soon she will buy me, a vessel and oars, to leave to distant lands with the Vikings…and to strike and fight.”

The Vikings brought the world to its knees, but the Viking Age began rather slowly. For a hunter to hunt effectively, he must first study his prey. As early as 793 and 799 C.E. Scandinavian raiders struck fast and hard in isolated areas of the known world. Following these abrupt and shocking attacks, a period of thirty or so years remained relatively calm. In Brittany, the first recorded attack saw the pillaging of the monastery of Saint Philbert on the island of Noirmoutier, but few further incursions occurred until the 830’s. Coastal defenses built by Charlemagne provided ample protection for the western Frankish Empire, but those defenses rapidly waned under the poor leadership of Louis the Pious. What the Franks failed to realize was that a new threat waited in the shadows, watching, lurking, and learning.

Historians agree that despite an early strike on Noirmoutier in 799 C.E. the Viking Age began much later in Brittany than in England or Normandy. The region had already developed a strong sense of Breton identity and frequently revolted against the Frankish Empire. By the early 9th Century, the Bretons had won their independence under the leadership of Nominoé, a charismatic politician and talented tactician. With this victory came the burden of independence: political organization, defenses, and economic ties. Unfortunately for the Bretons the timing could not have been worse for the Viking Age was about to spill into their lands.

In 843, Brittany experienced what they interpreted as the Apocalypse. Chroniclers struggled to find the words to describe the cold blooded reality of the events of the 24th of June, 843. The denizens of the city celebrated the festival of Saint John (La Saint Jean in French). Everyone participated, including the city guards. None thought to fortify the city for they had not imagined that God would allow anything to disturb their festivities. By the time the people of Nantes realized their sort, it was too late for them to organize any kind of resistance. It is proposed that the raiders had entered the city posing as merchants, but that under their cloaks they bore the weapons of Nantes’ demise. The bishop of Nantes, a man named Gunhardus, continued his sermon on the steps of the cathedral and proclaimed, “Sursum Corda!” (high hearts) before he was violently gutted before the townspeople. With no consideration for age, sex, or status, the Northmen slit the throats of all whom they could find. By evening, the city burned in ruin.

The retelling of this event comes to us from the Annales d’Angoulême compiled by nearby priories who rescued some of the survivors of the event. In the Annales, we learn that the Northmen were Westfaldingi, in other words Men of Westfold (a region on the continental coast of the Fjord of Oslo). Their movements had been traced and recorded as far as the Hebrides, and they ostensibly travelled through the Bay of Saint George to arrive in the Bay of Biscay where they improvised a raid on the Saint John festival. They continued along the Loire River and terrorized the Pays de Retz further inland. Once they had filled their ships they returned to the coast, but not without incident. Two of the fleet’s ships wrecked along the river, too heavy from their booty to keep afloat. Finally, the Northmen established a base on the nearby island of Noirmoutier where they stored and split their spoils. Some returned north, while others continued their voyage south. They avoided returning to the Loire thereafter, for the new count of Nantes, Lambert, fortified the Loire River’s banks to prevent a repeat of the monumental catastrophe in Nantes.

Some of the Northmen sailed as far as Spain where historians lose track of their movements. But the damage to the region had been done. The horror of the events reverberated across the Carolingian Empire, and nearly all the Annales, or chronicles, of the time make reference to the carnage of the sack of Nantes. Of course the Bretons seized the opportunity to solidify their independence from the empire, but the disunity on the Breton March would prove to be their demise. While the people hoped they had heard the last of their attackers, the Viking Age had formally begun in Brittany, and it would last for over a century.

By 847 C.E. it became clear that the Viking invaders of Western Europe had developed political ambitions beyond the sporadic raiding of the previous three decades. Their sights moved beyond Britain and Normandy to other, less defended lands such as Ireland and Brittany. At first, resistance was effective. For example, within one year the Irish won an unprecedented four victories over the Vikings which effectively expelled a tremendous portion of the invaders from Ireland. But That same year in Brittany, Viking raiders began an invasion of the mainland peninsula and won three decisive victories over the Bretons who at the same time were repelling an invasion from the Franks. The Vikings used Noirmoutier, an island in the Bay of Biscay, as their base to launch a massive invasion attempt and to supply the warriors involved. The resources of the island, salt, was a necessary resource for any army of the time, and the Vikings were no exception.

With great cunning and strategic thinking, the Vikings exploited the rift along the Breton March between the Franks and the Bretons. A struggling Breton army even solicited the help of the Vikings to help defeat the Frankish army on two separate occasions. Once defeated, the Franks could no longer defend their borders, and the Viking invasion quickly saw the sack and occupation of Nantes on the Loire. With Nantes under Scandinavian control, the great citadels of Brittany followed: Cornouaille, Broweroch, Poutrocoët, Domnoée, and finally Saint-Brieuc. Pitting the two sides against one another, the Vikings expertly divided the lands and conquered them. By 854 C.E. a state of full military occupation was in place. So it seemed, Brittany would remain under their dominion.

Vikings, however, were ambitious people. No two groups thought alike, and no two groups settled for sharing power. In Normandy, the heavy influence and frequent raids of Vikings changed the political landscape. Charles the Bald, king of France, began a campaign to use the variable alliances of the Vikings against them. On the Seine, Charles hired Vikings to defend certain areas of the river. Once secured, Charles turned his attention to Brittany where a powerful warlord, Salomon, ruled over a large area of the region. At first, Salomon appeared keen on an alliance with Charles; the Vikings in the Loire themselves had recently been troubled by raids from other groups. Charles offered Salomon land rights and the status of vassal. Unfortunately for Salomon, a simultaneous Danish raid on Chartres and Tours following the new alliance sent the counts of Neustria (Western France) into revolt. Charles was forced to cancel his promises to Salomon.

Free of the protectorship of Charles the Bald, the Vikings on the Loire suffered a heavy defeat by Robert the Strong, the leading Neustrian Count who had had enough of the Scandinavians invading his lands. The conflict ended in a stalemate. For the next 20 years a similar political and military climate dominated the region. Along the Seine the Vikings continued to sack and pillage, and the Franks continued to rebuild and attempt to mount a resistance. Along the Loire, things settled. It had more or less been decided that Brittany had been lost to the invaders.

As luck would have it for the Bretons, Salomon was murdered by his rival in 874. The ensuing power vacuum caused a civil war between the Vikings in which a Breton-Frankish alliance emerged to drive an even deeper wound into the heart of the occupiers. Hope glimmered a moment, until the realization that the power vacuum left by Salomon would attract more raiders with ambitions of their own. The raids intensified. An internal struggle again erupted between the Bretons and the Franks, causing the resistance to dissolve. Sole one leader remained with a guerrilla force to fight the Vikings: a man named Alain of Broweroch. Alain mounted an effective resistance and pestered the invaders constantly. His big break came when the Carolingians successfully pushed out the Seine Vikings who fled into Brittany and disrupted the power structure there. With a renewed civil war between the Vikings, Alain fielded two Breton armies and led them to repeated victories. By 892 Alain had completely expelled the Vikings from Brittany. Scandinavian fortunes were not good along the Seine either: the Great Danish Army left mainland Europe and sailed for England to focus on the kingdom of Wessex.

Alain the Great ruled over Brittany after the expulsion of the Vikings as a sovereign king not loyal to Charles the Bald. The Bretons saw the Franks as incapable of defending them, and thus loyalty to the empire served them no benefit. A period of peace ensued. Through military endeavor, judicious alliances, and payment of Tribute, Alain kept the peace in his lands. Upon his death in 907 C.E., his successor, Gurmhailon should have had no trouble keeping this peace. The system put in place by Gurmhailon’s predecessor quickly fell to pieces. Scandinavian invaders again sacked the Breton coast and began deep incursions into Breton lands. In this chaos, one man would emerge to put an end to this long struggle. One man would rise to become the first true and remembered Duke of Brittany.

Muddied and trite, the Bretons began a long period of restoration to repair damage done by the Vikings. Still, the overlords from the north seemed a new permanent feature to the Breton landscape. Raids intensified in the continuing decades after the apt Alain the Great — who expelled the Vikings under Solomon — died without a suitable or qualified heir. The situation grew more difficult when a Viking force comprised primarily of Danes sacked and occupied Nantes a second time. Defeated, the Bretons retreated to their countryside where they squabbled in civil war over who should lead them to victory against the invaders.

Then, a glimmer of hope appeared in 913 C.E. with the birth of a child. His legend says that saints attended his birth and he received many blessings. In actuality, his birth would have been as unremarkable as any other, only this child was the grandson of Alain the Great. Through a strangely contrived marriage, the child received an invitation from his godfather King Athelstan of Wessex to live under the protection of his kingdom. No manuscripts have survived which tell us of the child’s upbringing in England, but he emerged a giant among men. His name was Alain Barbe-Torte. He earned his name from the uneven cut of his beard, which was a trait he shared with his grandfather according to one chronicle.

Alain held all the virtues of an effective leader: charismatic, cunning, quick-whited, and of course full of the utmost prowess in combat. Upon his return he laid claim to the throne of Brittany. The little resistance he encountered was squashed. It took little more than a fortnight for Alain to gain support from the entire kingdom. Thus began one of the more aggressive and seldom known military campaigns of the Viking Age. Alain led an army beginning in Normandy where many Vikings entered into Brittany having been forced out of the Seine river valley by Charles the Bald. It is difficult to imagine that Vikings could be the victims of a massacre, but at the hands of Alain Barbe-Torte they certainly were.

After cleansing the northern territories of Brittany of the Vikings, Alain marched south: straight for Nantes. As they passed through Viking held villages Alain’s troops left a wake of devastation behind them. Further and further they marched into the Loire river territory, and the more nervous the usurpers of Nantes became. The final push besieged Nantes where, conveniently enough, a fresh fleet of Vikings had sailed up the river to sack the city. Alain recruited these Vikings to help him sack the city. His agreement with them included something unusual: a settlement charter. The agreement was that if these Northmen joined him in battle, Alain would grant them rights to fertile lands in the Loire River Valley; so long, of course, they also convert to Christianity. With a deal brokered, the two armies converged on a heavily fortified Nantes. Within two days the city was taken.

The end of the Viking Age was upon Brittany. After over a century of turmoil and strife, the invasions and raids subsided. This was due to a global slowing of the Scandinavian exodus that changed the world, as well as the harsh tactics utilized by Alain Barbe-Torte. Alain established a strict legal code in Brittany, as well as permanent coastal defenses, secured trade routes, and a navy capable of intercepting approaching fleets. The Bretons had reclaimed their independence. Breton Sovereignty lasted until the 15th Century when the dukes of Brittany finally accepted to join the kingdom of France.

June 26, 2014

The Chateau de Noirmoutier

The Chateau de Noirmoutier is one of the oldest castles in France and Europe. While not originally built in the moat and bailey style, the lords of the region in the medieval period refitted the castle with four large towers, an outer wall, and of course a moat. Originally built to defend the island against the Vikings, the Chateau de Noirmoutier has played a tremendous role in the history of the region. It has withstood assaults from a variety of enemies throughout the Middle Ages. In the early 18th century, the castle was home to Dutch engineers and businessman — with the last name of Jacobssen — who worked to build dikes and levies around the region known today as the Vendée, much of which was under water prior to the Dutch constructions. The entire operation was conducted to increase the production of salt from the region, as well as open up new fields for raising livestock. Noirmoutier island today is referred to in French as “use presqu’Ile”, or an “almost island”, because at low tide an overland passage connects the island to the mainland. Prior to the Jacobssens, however, the island was only connected to another island known as Bouin which today is no longer an island. During the Viking Age, Bouin was a popular town to pillage due to its separation from the mainland.

The Chateau de Noirmoutier also served as the last bastion of the Vendéen forces during the Guerre de Vendée, fought from 1793-1796. Vendée, a fiercely catholic and pious region, remained loyal to the king of France during the French Revolution. Republican forces entered the region and committed what many today consider to have been a genocide. A significant population was massacred. Pictured below is the execution of the leader of the Vendéen forces at the Chateau de Noirmoutier:

(photo: the death of Générale D’Elbée, executed in his chair. The chair, filled with bullet holes, is still on display at the castle)

Author C.J. Adrien is currently visiting the island and the chateau, and using his connections with the local historical association to access exclusive archives kept at the chateau. The history of the island, and the chateau, inspired his first novel, “The Line of His People”, and its unreleased sequel, “In the Raven’s Wake”, all based on the exploits of the Vikings in the region in the 9th century A.D.

The Line of his People is currently on sale no in the U.K., buy your copy today!