C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 26

April 26, 2014

A Finished Viking Shield

After painting with the colors of the shields of my protagonist in The Line of His People, I finished this bad boy up with rawhide around the edges. I am proud of myself, and I have also learned a great deal. Making shields is hard work, especially with the knowledge that they do not last long in battle. My shield has taken powerful hits already, and it has held firm; but a few weeks in the field would certainly destroy it. For now, it will be used decoratively, and for photo shoots. It has been a wonderful journey.

April 25, 2014

Early Resistance to the Vikings

In the early years of the Viking Age — 793-843 C.E. — the Scandinavian raiders used hit and run tactics to obliterate their foe. They also only attacked weak targets with highly mobile troops who had the ability to appear and disappear before any resistance could be mounted. The sensationalization of the early raids evoked fear in the populations of Western Europe who had not yet witnessed the horrors of Norse pirates; however, most people during these years were utterly safe from the clutches of the heathens. Charlemagne, the emperor of the Frankish empire, built coastal defenses to the mouths of rivers and along vulnerable settlements on the Atlantic. He had experience in dealing with raids as the Danes of Jutland had frequently plundered the coasts of Frisia (modern day Netherlands) as early as three decades before Lindisfarne. In the British Isles, the kingdoms of Wessex, Kent, Mercia, East Anglia, and Northumbria were a tightly controlled and highly militarized autocracies locked in a perpetual state of warfare. While the first Viking raids shocked them due to the random nature of the first attacks, the kingdoms mounted fairly effective resistance to the Norwegian raiders (mentioned as Vestfaldingi, or men of Vestfold, in the Chronicles of Bertin).

Looking back at this early period in the Vikings Age, one might conclude that the early raids were a dismal failure characterized by a spattering of attempted attacks on well fortified positions accompanied by severe casualties and loss of ships. Furthermore, no notable historic leaders appear to have taken part in any raids: kings and wealthy earls had no incentive to leave their lands and risk defeat at the hands of the Christians. Thus, the Vikings in the early days of raiding were less important free men who yearned at a chance for glory and wealth through their violent enterprise. It was not until the dissolution of the Frankish Empire under the treaty of Verdun in 843 C.E. that Scandinavian raiders began to effectively pillage the coasts of Europe, and even sail up river to sack major cities such as Nantes (in 843 C.E.), Paris (in 845 C.E.), Utrecht (in 850 C.E.), and York (in 866 C.E.). It was during this second phase that the Vikings began to leave their mark on history.

April 22, 2014

The Viking Hauberk

DID YOU KNOW that the Vikings seldom used Hauberks? For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term hauberk, it is simply a chain mail shirt described as “reaching to the hip and with sleeves”. Indeed, the Vikings did not commonly wear such armor for economic reasons. Hauberks in the time of the Vikings were exceedingly expensive. Thus, only the wealthiest, most powerful warriors could afford to make and field such armor. Then again, to wear a Hauberk into battle could prove dangerous because the enemy might target the wearer specifically to steal the hauberk! It should be noted, however, that a vast contrast exists between the eastern and western Scandinavians of the Vikings Age. Archeological digs in the east, such as along the Dnieper and Volga rivers, have uncovered far fewer Hauberks compared to their other artifacts than in western digs. The Rus disliked the confinement of a hauberk, and the Varangian guard in Constantinople has never been described as wearing a full hauberk. Conversely, western Vikings wore a great deal more chain mail. A possible reason for this may have been the availability of hauberks across the Frankish Empire. Hauberks could be taken from the slain in battle, as well as be stolen from weapon stores in fortified areas. The Franks equipped a large portion of their soldiers with chain mail.

In the novel The Line of His People the protagonist Abriel encounters this interesting fact of history when he is gifted a hauberk, which sets him apart from the other Northmen who preferred hardened leather. In his ignorance, Abriel wore the hauberk.

April 21, 2014

C.J. Adrien on Location

Above is C.J. Adrien standing in front of the Abbey of Saint Philbert on Grand Lieu Lake. The abbey was originally a satellite priory to the monastery of Saint Philbert on the island of Noirmoutier, but following the Viking raids which began in 799 A.D. the order of monks moved inland to avoid their aggressors. The relics from the original monastery were thought to have been lost during the Scandinavian raids, but were recovered in the mid 9th century and brought to the abbey seen here, and then dispersed amongst the multitude of churches and monasteries devoted to Saint Philbert thereafter. In recent history, the monastery had been abandoned for many years until the local municipality decided to renovate in the last twenty years. Archeological digs on the grounds have revealed many interesting artifacts. This small abbey is the site of the first chapter of C.J. Adrien’s novel, “The Line of His People”.

April 20, 2014

The Building of My First Viking Shield

I began with a question: could I build a viking shield using nothing but materials I have at my house? What began as a question endured as a quest to test how far I was willing to go for my passion for vikings. A good starting place was my woodpile out back. There I found leftover planks from the building of the back porch, all still in relatively good condition. Using a sharpie and some measuring tape, I outlined the round shield from seven planks. I measured the radius at 16 inches, so three inches longer than my forearm. Then came the sawing. How hard in sawing in a curve? Let’s just say it’s not as fun as one might think. Once the pieces were cut, I assembled them in order and formed the shield. I used advice from a few aficionado sites to make the strongest design and hammered everything into place. And voila!

Next came the hard part: the shield boss. Where would I find an iron boss to fit a Viking shield in a small rancher town in Oregon? Well, it turns out ranching supply stores have everything you can think of, including a cast iron range top cover that looked, felt, and acted like a real shield boss. I used a jigsaw to cut my hole in the center of the shield, and bolted the boss on without difficulty. Finally, I fashioned a piece of wood into a handle with a file and hammered everything together to great my first functional viking shield:

We bashed it with axes, shot it with arrows, and it is still in great shape. Next I will paint the shield and trim it with rawhide, but more or less this adventure is complete. I feel accomplished. Using the shield has also taught me a great deal about the feeling of wearing a shield, and has informed my writing tremendously. What will my shield and I do next? We shall see!

April 19, 2014

Remembering Joshua the Pacifist

Tomorrow is Easter, and while I will not personally celebrate the holiday for my own reasons, I will make it a point to remember an inspirational story about a man who fought for peace in times of war; for equality in times of oppression. I am of course referring to Joshua from Galilee — Jesus is a Greek translation of the Hebrew name — a humble carpenter’s son with a vision for a better world. Israel at the time of the crucifixion was under foreign occupation. The Romans controlled many aspects of daily life in a well managed oligarchy under the rule of an ambitious soldier-turned-politician named Pontius Pilot. Resources were scarce, and the Romans drained the local economy for their own gain.

Joshua was a pacifist who objected to the brutality of Rome’s authoritarian rule. To combat the oppressors, he took the path of non-violence (as Ghandi would 2000 years later against the British Empire). In an age of violence, non-violence seemed foreign to the denizens of Jerusalem. With charisma, cunning, and a little touch of showmanship Joshua gathered support from many people — not the masses as the Bible would have us believe — and offered the first real resistance to the Roman Empire since the conquests carried out by Flavius Josephus. I like to think of the Pharisees as an insecure institution dependent on their overlords, comparable to the Vichy collaboration government in France in World War II.

Today, the story of Joshua is relatively well known, but his message has been twisted around in some horrendous ways. Son of God? I cannot say. But I guarantee the Bible cannot say either. The name Jesus is a greek translation for Joshua, given to us in that form because the first new testament Bibles distributed were created in Greece. Since then the new and old testaments have undergone many, many translations and rewritings, the end product of which is a document that is very different than what was originally written. Anyone who speaks more than one language knows that everything does not always translate exactly, and thus substitutions must be made, particularly when dealing with idiomatic expressions. Anyone who has ever played the game “telephone” also knows that even among speakers of the same language, simple phrases can and will change dramatically. Bibles are no different. In the Middle Ages, monks copied bibles for distribution and often changed parts of the text. One need look no further than preserved Bibles from the medieval period to find texts riddled with marginal notes, each changing some small piece of the previous version. Later on, kings ordered changes in Bibles for their own purposes which made new versions still available today (like the King James Bible). Have you ever wondered why there are so many different versions of the Bible on the book shelf at your local book store? Any literal interpretation of the Bible is a mistake. Anyone who says the Bible is the direct word of God is terribly misinformed. The Bible itself confirms it: it is recognized in the story of the Tower of Babel that languages would divide human populations; and this applies to the written word as well.

In any case, the story of Joshua is one to be remembered. Like the Norse, Greek, and Babylonian myths it has a lesson to teach for our betterment. It serves as a reminder of what people are capable of in times of oppression. We learn about love, compassion, peace, and non-violence. As a lesson, the story of Joshua is an informative piece that explores human nature and the terrible things people are capable of in the presence of fear. It is perplexing to me that this story be so well known and worshipped by many, yet our world has still come too close to self annihilation in war, greed, and discord. It would seem the same traits of human nature displayed by the antagonists to Jesus’ story are still in play today. This Easter, I will remember the man, his message of peace, and most of all, his efforts to end corruption in human organizations. Help thy neighbor, lay down your arms, love thyself and others. These are good messages, let us not use them for hate.

April 18, 2014

Vikings Episode 208 Earns High Marks for Writing

Again, the drama continues in beautiful fashion with Ragnar’s deformed son’s birth, Lagertha asserting her power, and the growing bond between Rollo and his nephew. Rollo, in my opinion, is the most intriguing and well developed character in the series. He is fallible, but has a strong moral center which always pulls him back. I am happy that he is picking up the slack for Ragnar in helping Bjorn develop as a warrior. Ragnar’s hubris is getting the best of him, which is consistent with human nature. Floki’s attitude towards Ragnar is a very interesting development, and he too wrestles with his own success within the shadow of his former friend. Thus far, the episode is everything I have come to expect from Vikings.

Where does the episode go wrong? Eh, I am enjoying the series too much to nitpick anymore. The writers are doing something very right: they are keeping the main plot and character stories compelling and interesting. Each character is different and appeals to different types of viewers. As mentioned before, I believe Rollo is the most interesting character. He speaks to me insofar as he makes mistakes, he accepts his flaws, and makes the best of ever situation he enters. He experienced the most hardship in sacrifice for Ragnar’s ascension and received the least among of recognition from his peers. Arguably, the peer I speak of all died in season one.

This continues to be the best show on television, so keep watching, keep enjoying, and most of all have fun!

King Arthur Was Not English

The anglophone world is all too willing to assume that the legend of King Arthur originated in England, and is thus English. King Arthur’s legend in reality likely originated outside of the British Isles. Many people have heard of the alternative versions of the myth, including Arthur’s humble beginnings as Arthurius, a Roman centurion. All of these are as fabricated as the English myth. The myth does, however, begin with the Romans, but not in the way Hollywood has attempted to portray it. It certainly does not begin in England; it begins in Bretagne.

We begin with a simple but important fact: the Romans kept impressive records. In Bretagne — Brittany in English — archeological digs of Roman sites have uncovered a large array of evidence to paint a fairy accurate picture of the region under Roman control at the end of the 4th century (Under Emperor Valentinius). We know for sure that there were several large garrisons on the peninsula, as well as what the Romans called an “Atlantic Wall”. The wall served to protect settlements from coastal raiders. No, these were not the Vikings, though they resembled them closely. These raiders were the Franks. Prior to their vast expansion under Clovis, the Franks had a rich maritime tradition, which they eventually abandoned to pursue conquests on land in the vacuum left by the collapse of the Roman Empire. Furthermore, we also know that the Roman prefect in control of Bretagne (known then as Armorica) in the early 5th century also managed the failing and shrinking Provincia Britannia (Great Britain). At the end of Roman rule in England in the 5th century, a mass exodus of Britons fled to Bretagne to which they lent their name.

The Romans withdrew from Britain and stationed their troops in Armorica to attempt to protect the mainland from barbarian invasion. It is here that the mythic Arthur would have made his triumphant debut as the defender of the Britons. There are no viable candidates who fit the bill exactly; the legend could have originated from any number of brave warriors during the ensuing wars at the collapse of the Roman Empire. In 405 C.E. a particularly cold winter allowed masses of Germanic peoples to cross the frozen Rhine river into Gaul where the Romans would attempt to stop them. This accumulation of Franks, Ostrogoths, and Visigoths pressured the Romans to act. The Romans knew that the Britons had fought these barbarians before, and thus their garrisons were called forth to defend the empire in a series of brutal conflicts in the north of Gaul. Among the Britons was general Gerontius, a candidate for Arthur of sorts, who united split factions of the Roman army to withstand a massive campaign by the Germans. Unfortunately, Gerontius was killed in battle.

Now that we understand the course of historical events, which is important in deciphering the myth in terms of place names, we can analyze the myths themselves. Armorica, or Bretagne, was known after the Roman period as Britain, whereas modern day England would only much later reclaim its name as Great Britain. We must also recognize that the population of Bretagne at the time was more homogeneously Briton than England who had already intermingled heavily between the Angles, the Saxons, the Britons, and the varieties of other tribes present (welsh, pict, etc). Therefore, when Arthur claims he is “King of the Britons” he is referring to the Britons of Bretagne, not England.

Then there are the legends. Sir Thomas Mallory was the first to write the legend in his masterpiece Le Mort D’Arthur (a French name) in which he makes no distinction between which Britain, and which Britons, Arthur was king of. Because he was English, and because he wrote the legend in English, it was assumed he wrote about the English. Across the English channel, Chrétien de Troyes wrote his Arthurian legend, Lancelot du Lac, in which we all know he added a typically French knight who slept with the king’s wife. Mallory later wrote in a journal of his contemporary, “leave it to a Frenchman to take a perfectly goode English tale and ruin it with adultery”. While humorous, this small change in the story is an important one. Lancelot was the French knight, with a French name (this is true of both Mallory and de Troyes). Following the logical composition of name etymology, that must mean that Camelot must have been French as well (Lancelot, Camelot). The most compelling evidence in the legend that points to Arthur being French is that it is recognized throughout in the first writings of the legend that all the events occurred on the mainland (i.e. continent), and that Arthur would only sail to the “Isle of Avalon” after his death.

During the 100 year’s war, the legend took new significance. The king of England wanted to rally the support of his knights by creating the Order of the Garter, an Arthurian based organization for knights which included a round table. It was during this time that the divide between Arthur’s national origins began. Similarly, the king of France created the Order of the Star, similarly based on the Arthurian legends. Thus, the legend of Arthur, king of the Britons, has since been the subject of controversy and disagreement between the French and the English (although, what hasn’t?). I assure you, however, that Arthur was most certainly not British nor French. He was Briton, from Brittany. If you visit Bretagne today, you can even walk the path supposedly walked in the enchanted forest were he removed excalibur from a stone. Finally, a song:

Ils ont les chapeaux ronds,

Vive la Bretagne,

Ils ont les couilles en plomb,

Vive les Bretons!

(They have big round hats,

Long live Brittany,

They have balls of steel,

Long live the Britons)

April 17, 2014

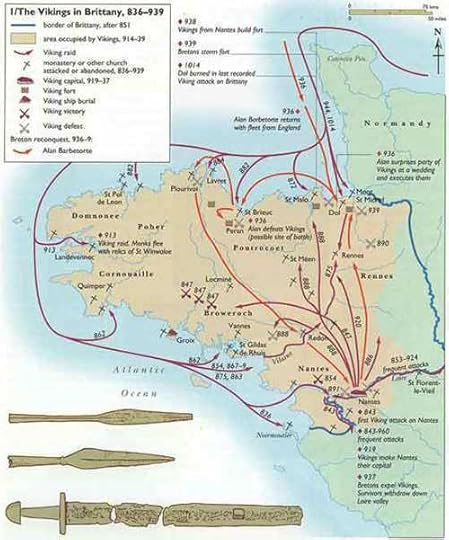

Vikings in Brittany: Part III

Muddied and trite, the Bretons began a long period of restoration to repair damage done by the Vikings. Still, the overlords from the north seemed a new permanent feature to the Breton landscape. Raids intensified in the continuing decades after the apt Alain the Great — who expelled the Vikings under Solomon — died without a suitable or qualified heir. The situation grew more difficult when a Viking force comprised primarily of Danes sacked and occupied Nantes a second time. Defeated, the Bretons retreated to their countryside where they squabbled in civil war over who should lead them to victory against the invaders.

Then, a glimmer of hope appeared in 913 C.E. with the birth of a child. His legend says that saints attended his birth and he received many blessings. In actuality, his birth would have been as unremarkable as any other, only this child was the grandson of Alain the Great. Through a strangely contrived marriage, the child received an invitation from his godfather King Athelstan of Wessex to live under the protection of his kingdom. No manuscripts have survived which tell us of the child’s upbringing in England, but he emerged a giant among men. His name was Alain Barbe-Torte. He earned his name from the uneven cut of his beard, which was a trait he shared with his grandfather according to one chronicle.

Alain held all the virtues of an effective leader: charismatic, cunning, quick-whited, and of course full of the utmost prowess in combat. Upon his return he laid claim to the throne of Brittany. The little resistance he encountered was squashed. It took little more than a fortnight for Alain to gain support from the entire kingdom. Thus began one of the more aggressive and seldom known military campaigns of the Viking Age. Alain led an army beginning in Normandy where many Vikings entered into Brittany having been forced out of the Seine river valley by Charles the Bald. It is difficult to imagine that Vikings could be the victims of a massacre, but at the hands of Alain Barbe-Torte they certainly were.

After cleansing the northern territories of Brittany of the Vikings, Alain marched south: straight for Nantes. As they passed through Viking held villages Alain’s troops left a wake of devastation behind them. Further and further they marched into the Loire river territory, and the more nervous the usurpers of Nantes became. The final push besieged Nantes where, conveniently enough, a fresh fleet of Vikings had sailed up the river to sack the city. Alain recruited these Vikings to help him sack the city. His agreement with them included something unusual: a settlement charter. The agreement was that if these Northmen joined him in battle, Alain would grant them rights to fertile lands in the Loire River Valley; so long, of course, they also convert to Christianity. With a deal brokered, the two armies converged on a heavily fortified Nantes. Within two days the city was taken.

The end of the Viking Age was upon Brittany. After over a century of turmoil and strife, the invasions and raids subsided. This was due to a global slowing of the Scandinavian exodus that changed the world, as well as the harsh tactics utilized by Alain Barbe-Torte. Alain established a strict legal code in Brittany, as well as permanent coastal defenses, secured trade routes, and a navy capable of intercepting approaching fleets. The Bretons had reclaimed their independence. Breton Sovereignty lasted until the 15th Century when the dukes of Brittany finally accepted to join the kingdom of France.

April 13, 2014

Question and Answer Session with C.J. Adrien

Thank you to all who participated in the question and answer session.

James Dixon asked: “If you were transported, as you stand, back to those times and knowing what you know, would you embrace it or would you want to come back. (you can take loved ones and teabags).”

I would want to come back for two major reasons:

The bacteria and diseases of today have evolved to be more ferocious than 1000 years ago. Our present day immune systems can resist infection, but as a denizen of the present, I carry pathogens that would have a devastating effect on the population of Viking Age Europe. In essence, by simply showing up, I would bring about a new plague whose consequences would have dire implications for the present. That is my pseudo-scientific response to the question. This is all assuming of course that the Grandfather Paradox is not applied.

Assuming that none of what was stated above were true, I would certainly enjoy exploring Viking Age Europe. However, seeing as my modern sensibilities make me avert to the act of killing, I would certainly be rapidly introduced to a way of life unfamiliar to me. It is easy to read of the killings of people in books, but to witness them in person is an entirely different affair. We must remember that the Dark Ages were an age of violence and the value of human life was much less than what we give it today. There was also much less stringent concepts of law and right and wrong. Safety was a major issue back then that we take for granted today. Therefore, it would be interesting to visit, see how how they lived, but I certainly would want a way home to the present.

Acorn Everhart asked: “Was Oak the only type of wood Vikings used to make Dragonships and Knarrs? Greenlanders would have had to switched to pine from Markland at some point not being able to rely on oak shipments from Norway.”

The tradition of seafaring in Scandinavia began with the Franks of the 4th century who left their homes to raid west. Think of it as a Viking Age before the Viking Age. They harassed the Romans to no end in ships that closely resembled the long ships of the Vikings. That seafaring tradition was transferred across the baltic to become the engineering pride of the Dark Ages. The wood they used varied greatly depending on location and availability. One of the great wonders of the long ship was the design was simple enough that they could be built out of anything. During the Viking Age, ships were primarily built from ash, birch, spruce, pine, oak, and alder. An archeological find on the island of Groix in the Bay of Biscay (France) determined a Viking ship to be made of a combination of oak, ash, and even some aspen! Needless to say, the Vikings were very resourceful.

Many thanks again to all the participants. I hope you enjoyed the session, and watch for the next question and answer submissions!