C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 27

April 11, 2014

Vikings Episode 207: The Lamentable Curse of a Good Run.

Up until this point I have fought hard to give Vikings good press; and deservingly so. Blood Eagle, however, made huge mistakes at several critical junctures in the storyline. First, the tale of Ecbert in Wessex is a vexing assortment of some misguided attempt at appeasing English national pride. Second, the tale of Floki and his new wife has diverged from mainstream history and entered the halls of fantasy. En revanche, the Blood Eagle was a marvelous spectacle: a slow buildup, dramatic cut scenes, and a final opaque glimpse at the horror. Was the blood Eagle accurate? This episode as a whole fell victim to the lamentable curse of a good run for it did not rise to the high expectations the previous episodes set for it.

The scene where the kings of Wessex and Northumbria meet vexed me. Their meeting included a most unusual homage to England with the chant “God Save England”. To put this Take 5 Productions idiosyncrasy into analogous perspective, the island they refer to as England was not referred to as such in the Viking Age. No, the island was known as Britain, a name given to it by the Romans. In fact, the region of France known as Brittany (Bretagne) also derives its name from the same source: Rome placed modern England and Brittany under the same prefecture. Nor did the British Isles have any modern sense of national coherence. Shortly prior to the Viking Age, the island had been invaded by Saxons and Angles, Germanic tribes who escaped the villainy of the Franks in the 5th century. Britain was a divided region. In fact, it was king Ecbert, years after the supposed time of the Vikings series, who conquered the small kingdoms around him to become the first proto-king of Britain; only to split apart again a few years later due to the deep divisions between the people of the region. The name England only surfaced in the beginning of the Middle Ages (some 200 years later) after the Norman conquest. England was lent its name by the Angles, a tribe of Germans who settled Britain with the Saxons. “God Save England” was a horrendous faux-pas.

Floki’s wedding also vexed me. Vikings exchanged dowries at weddings, not rings. Our tradition of exchanging dowries comes from the Vikings. A marriage in Viking Age Scandinavia was a contract in which both parties entered as equals, but the woman kept the dowries in case the husband died in battle. This was to ensure that the property rights passed to the wife upon the death of her husband. This was neither discussed nor explained in the show, nor adhered to as a historical fact. A deep ritual cleansing would have preceded the ceremony, which we did not see either. The wedding was a tremendous opportunity for the show to demonstrate a deeper understanding of how the Vikings conducted a wedding ceremony and its significance in the community. To this effect, they failed.

Lastly, the blood eagle delivered everything it promised. A colleague of mine asked me about my thoughts on the historical accuracy of the act. He was shocked that the Vikings would have been capable of such a horrific execution; and in public? Historically, the only evidence for the blood eagle comes to us from Adam of Bremen who briefly mentions the execution method. There is no other evidence, literary or otherwise, to substantiate whether or not this was an actual practice. Historians agree, however, that the act may have actually been used because human cultures have demonstrated repeatedly in history the ability to do horrific things to one another. In Japan, ritual suicides where the defeated party cut into his own stomach, removed his entrails, and presented them to his conquerors before being beheaded (Sepuku, or Hara Kiri) was a prolific cultural practice. As late as the 1950’s in the United States, courts ordered public hangings where families took their children for picnics. Therefore, I feel confident that the Vikings would have been capable of carrying out such an act. Does that meant they actually did it? No. But hey, this is historical fiction, they are allowed some fun!

Other than the blatant errors listed above, the drama of the show did not cease. I look forward to the next episode, but as of today I am not going to pay as close attention to the historical details and watch the show for what it is, entertainment. Vikings has begun caring less about the history and more about the Game of Thrones-esque plots which drive audiences. I understand this, and I accept it.

April 8, 2014

The Vikings in Brittany Part 2

By 847 C.E. it became clear that the Viking invaders of Western Europe had developed political ambitions beyond the sporadic raiding of the previous three decades. Their sights moved beyond Britain and Normandy to other, less defended lands such as Ireland and Brittany. At first, resistance was effective. For example, within one year the Irish won an unprecedented four victories over the Vikings which effectively expelled a tremendous portion of the invaders from Ireland. But That same year in Brittany, Viking raiders began an invasion of the mainland peninsula and won three decisive victories over the Bretons who at the same time were repelling an invasion from the Franks. The Vikings used Noirmoutier, an island in the Bay of Biscay, as their base to launch a massive invasion attempt and to supply the warriors involved. The resources of the island, salt, was a necessary resource for any army of the time, and the Vikings were no exception.

With great cunning and strategic thinking, the Vikings exploited the rift along the Breton March between the Franks and the Bretons. A struggling Breton army even solicited the help of the Vikings to help defeat the Frankish army on two separate occasions. Once defeated, the Franks could no longer defend their borders, and the Viking invasion quickly saw the sack and occupation of Nantes on the Loire. With Nantes under Scandinavian control, the great citadels of Brittany followed: Cornouaille, Broweroch, Poutrocoët, Domnoée, and finally Saint-Brieuc. Pitting the two sides against one another, the Vikings expertly divided the lands and conquered them. By 854 C.E. a state of full military occupation was in place. So it seemed, Brittany would remain under their dominion.

Vikings, however, were ambitious people. No two groups thought alike, and no two groups settled for sharing power. In Normandy, the heavy influence and frequent raids of Vikings changed the political landscape. Charles the Bald, king of France, began a campaign to use the variable alliances of the Vikings against them. On the Seine, Charles hired Vikings to defend certain areas of the river. Once secured, Charles turned his attention to Brittany where a powerful warlord, Salomon, ruled over a large area of the region. At first, Salomon appeared keen on an alliance with Charles; the Vikings in the Loire themselves had recently been troubled by raids from other groups. Charles offered Salomon land rights and the status of vassal. Unfortunately for Salomon, a simultaneous Danish raid on Chartres and Tours following the new alliance sent the counts of Neustria (Western France) into revolt. Charles was forced to cancel his promises to Salomon.

Free of the protectorship of Charles the Bald, the Vikings on the Loire suffered a heavy defeat by Robert the Strong, the leading Neustrian Count who had had enough of the Scandinavians invading his lands. The conflict ended in a stalemate. For the next 20 years a similar political and military climate dominated the region. Along the Seine the Vikings continued to sack and pillage, and the Franks continued to rebuild and attempt to mount a resistance. Along the Loire, things settled. It had more or less been decided that Brittany had been lost to the invaders.

As luck would have it for the Bretons, Salomon was murdered by his rival in 874. The ensuing power vacuum caused a civil war between the Vikings in which a Breton-Frankish alliance emerged to drive an even deeper wound into the heart of the occupiers. Hope glimmered a moment, until the realization that the power vacuum left by Salomon would attract more raiders with ambitions of their own. The raids intensified. An internal struggle again erupted between the Bretons and the Franks, causing the resistance to dissolve. Sole one leader remained with a guerrilla force to fight the Vikings: a man named Alain of Broweroch. Alain mounted an effective resistance and pestered the invaders constantly. His big break came when the Carolingians successfully pushed out the Seine Vikings who fled into Brittany and disrupted the power structure there. With a renewed civil war between the Vikings, Alain fielded two Breton armies and led them to repeated victories. By 892 Alain had completely expelled the Vikings from Brittany. Scandinavian fortunes were not good along the Seine either: the Great Danish Army left mainland Europe and sailed for England to focus on the kingdom of Wessex.

Alain the Great ruled over Brittany after the expulsion of the Vikings as a sovereign king not loyal to Charles the Bald. The Bretons saw the Franks as incapable of defending them, and thus loyalty to the empire served them no benefit. A period of peace ensued. Through military endeavor, judicious alliances, and payment of Tribute, Alain kept the peace in his lands. Upon his death in 907 C.E., his successor, Gurmhailon should have had no trouble keeping this peace. The system put in place by Gurmhailon’s predecessor quickly fell to pieces. Scandinavian invaders again sacked the Breton coast and began deep incursions into Breton lands. In this chaos, one man would emerge to put an end to this long struggle. One man would rise to become the first true and remembered Duke of Brittany.

April 5, 2014

The Vikings in Brittany Part 1

Introduction: As part of my efforts to educate the public about the Vikings, I thought it pertinent to do an in-depth series on the Vikings in Brittany. Brittany is a region of France which survived a violent and catastrophic period during the Viking Age from which they emerged weakened and unable to remain independent from the larger Carolingian Empire. Most of the information about the Viking Age focuses on England, but the Vikings affected the entire world. It is important to understand how they interacted with other regions and cultures to foster the most complete understanding of who they were and their intentions. Enjoy!

A skaldic verse from Egill Skallagrimson paints the picture of what once was considered the perfect Viking; created impatient from birth, presumptuous, and with a burning desire for a far-off adventure:

“My mother promised me, and soon she will buy me, a vessel and oars, to leave to distant lands with the Vikings…and to strike and fight.”

The Vikings brought the world to its knees, but the Viking Age began rather slowly. For a hunter to hunt effectively, he must first study his prey. As early as 793 and 799 C.E. Scandinavian raiders struck fast and hard in isolated areas of the known world. Following these abrupt and shocking attacks, a period of thirty or so years remained relatively calm. In Brittany, the first recorded attack saw the pillaging of the monastery of Saint Philbert on the island of Noirmoutier, but few further incursions occurred until the 830’s. Coastal defenses built by Charlemagne provided ample protection for the western Frankish Empire, but those defenses rapidly waned under the poor leadership of Louis the Pious. What the Franks failed to realize was that a new threat waited in the shadows, watching, lurking, and learning.

Historians agree that despite an early strike on Noirmoutier in 799 C.E. the Viking Age began much later in Brittany than in England or Normandy. The region had already developed a strong sense of Breton identity and frequently revolted against the Frankish Empire. By the early 9th Century, the Bretons had won their independence under the leadership of Nominoé, a charismatic politician and talented tactician. With this victory came the burden of independence: political organization, defenses, and economic ties. Unfortunately for the Bretons the timing could not have been worse for the Viking Age was about to spill into their lands.

In 843, Brittany experienced what they interpreted as the Apocalypse. Chroniclers struggled to find the words to describe the cold blooded reality of the events of the 24th of June, 843. The denizens of the city celebrated the festival of Saint John (La Saint Jean in French). Everyone participated, including the city guards. None thought to fortify the city for they had not imagined that God would allow anything to disturb their festivities. By the time the people of Nantes realized their sort, it was too late for them to organize any kind of resistance. It is proposed that the raiders had entered the city posing as merchants, but that under their cloaks they bore the weapons of Nantes’ demise. The bishop of Nantes, a man named Gunhardus, continued his sermon on the steps of the cathedral and proclaimed, “Sursum Corda!” (high hearts) before he was violently gutted before the townspeople. With no consideration for age, sex, or status, the Northmen slit the throats of all whom they could find. By evening, the city burned in ruin.

The retelling of this event comes to us from the Annales d’Angoulême compiled by nearby priories who rescued some of the survivors of the event. In the Annales, we learn that the Northmen were Westfaldingi, in other words Men of Westfold (a region on the continental coast of the Fjord of Oslo). Their movements had been traced and recorded as far as the Hebrides, and they ostensibly travelled through the Bay of Saint George to arrive in the Bay of Biscay where they improvised a raid on the Saint John festival. They continued along the Loire River and terrorized the Pays de Retz further inland. Once they had filled their ships they returned to the coast, but not without incident. Two of the fleet’s ships wrecked along the river, too heavy from their booty to keep afloat. Finally, the Northmen established a base on the nearby island of Noirmoutier where they stored and split their spoils. Some returned north, while others continued their voyage south. They avoided returning to the Loire thereafter, for the new count of Nantes, Lambert, fortified the Loire River’s banks to prevent a repeat of the monumental catastrophe in Nantes.

Some of the Northmen sailed as far as Spain where historians lose track of their movements. But the damage to the region had been done. The horror of the events reverberated across the Carolingian Empire, and nearly all the Annales, or chronicles, of the time make reference to the carnage of the sack of Nantes. Of course the Bretons seized the opportunity to solidify their independence from the empire, but the disunity on the Breton March would prove to be their demise. While the people hoped they had heard the last of their attackers, the Viking Age had formally begun in Brittany, and it would last for over a century.

Love the Vikings? Check out C.J. Adrien’s novel on the Vikings in France here.

April 4, 2014

In The Raven’s Wake cover reveal!

Click the cover to read the prologue to C.J. Adrien’s next viking epic! Est. Release Date: Winter 2015.

History Channel’s Vikings Does Not Disappoint

Episode six of Vikings had the feel of a Game of Thrones episode more than the usual Vikings. A few elements have led me to this conclusion. Indeed, there is still a great deal of history covered in the episode, specifically in the tale of Athelstan and his relationship with Ecbert, but the developments in the pot were the most compelling aspect of this episode even for a historian. In Kattegat, the deep character development and twists in the plot set the scene for a complicated and strange series of events reminiscent of George R. R. Martin’s fascinating yet disturbing creativity. This short review will present some plot spoilers. To view the episode online first, click here.

First, Jarl Borg’s fascination with his wife’s skull, and his unbelievably disturbing interaction with it, point to a man whose sanity has left him in the wake of a broken ego. To make his young wife carry the skull for him demonstrates his lack of apathy for anyone else’s feelings. Second, Siggy’s power play backfired terribly to the point where her choices put her in an unusual situation. Horik on his end is a perverted egomaniac, but we all already knew. Yet, it still surprises and shocks that Horik forces Siggy to initiate an intimate act with his son only to watch from the comfort of his bench. These details are fit for a Game of Thrones episode, but they fit in well with Vikings insofar as the character development and plot have made for a darkly captivating story.

Finally, the detail that sticks in my mind is the Blood Eagle. I admit, I am somewhat infuriated that the show has thrown in yet another element found in my novel; I suppose our research comes from the same bodies of work. In terms of good show making, the Blood Eagle will not disappoint. For those of you who did not understand entirely what it entails, allow me to introduce it to you through the narrative of my novel:

“Light shone through the cracks of the poorly constructed shack, partly illuminating the interior. Horror overcame Kenna. Upon waking she saw a sight beyond horrific — so disturbing that even the brave princess averted her eyes. Kenna look up again, extremely disturbed by the sight of a man nailed to the opposite wall. The man’s body faced away from Kenna, his hands pronated against the wall with nails driven into them. His bare back left exposed, the man’s ribs had been removed from behind, and his lungs pulled through the gap like wings, reddened with various shades of blood. Thus the name, Blood Eagle, signified giving a man wings like an eagle using his own lungs. As Kenna studied the sight in disgust, she heard a calling from across the farm.”

In all, episode six was intriguing, entertaining, and certainly worth viewing more than once.

April 3, 2014

Vikings: A Culture of Learning

History has falsely remembered the Vikings as brutish, amoral barbarians with no respect for their victims. What we know of the vikings comes to us from the works of Christian clerics (the only literate people of Viking Age in Europe) who vilified the raiders from the north due to their hostile actions against monastic orders. These were the only materials available to the scholars of the 19th century who began to piece together the history of the Viking Age. Their conclusions have lent to the stereotypical frameworks of the Vikings we have grown accustomed to in literature and the media. In the last twenty years however, the misrepresentation of the people we know today as the vikings has redressed; new finds and evidences point to a much more cultured and intellectual population. Archeologists, historians, and medievalists now acknowledge that our previous understanding of Scandinavian culture in the early medieval period was wrong. A more holistic approach to the field has shown us that indeed Viking Age Scandinavians had rich traditions, and most importantly, a culture of learning.

The culture of learning in Viking Age Scandinavia begins with a myth. Norse mythology was central to the establishment of Scandinavian institutions and power structures, as well as cultural life and social expectations. In particular, the myth surrounding the nature of the leader of the Aesir, or Norse deities, resonates profoundly even today among many who ascribe to Norse paganism. Odin, creator of men, obsessed over knowledge. He prided himself on his ability to learn and to apply that learning to his life (see The Norse Gods Were Mortal). His obsession led him to take extreme measures. In fact, Odin discovered a way to learn about the future, about the end of the world known as Ragnarok. This knowledge unfortunately carried a price. Mimir, the guardian of the well of knowledge, demanded a sacrifice of an eye. Odin obliged.

The myth serves as a counterpoint to the old paradigms of scholarship on Viking Age history. Odin, the most beloved deity in the Norse pantheon, strived for knowledge. To make a modern analogy, it is as if Justin Bieber suddenly decided to attend college for his own self enrichment. Following suit, we may rightly conclude that such a decision would have a dramatic influence on an entire generation of devotees, and college attendance would soar. Similarly, we may assume that Odin’s thirst for knowledge would have influenced generations of Scandinavians to explore their curiosity without hinderance. Even with the backing of a myth, however, such a claim requires more tangible evidence to be supported; lest we allow ourselves to fall into the trap of historians past.

As it turns out, archeology has provided evidence that Viking Age Scandinavians imported more than loot. One example is the finding of a sword, the Ulfberht, whose construction required a technology not available to most of Europe until hundreds of years later. Analysis of the metals in the sword have shown the steel’s purity to be nearly that of crucible steel. What does that mean? Simply put, the purity of the steel would have required temperatures higher than any fire made by any blacksmith in Europe at the time. The technology to produce such an artifact tells us that the Norse must have learned the technique elsewhere, likely in the east. This was possible due to the exploits of the Swedish vikings known as the Rus who traveled across the eastern steppes of modern day Russia as far as the Black Sea and beyond. Trades and cultural exchanges were common — to the point where an 11th century Arabic silver coin was found in Newfoundland! The vikings, we now know, attained many advances and much wealth as a result of their travels.

Archeologists have also found more evidence of technological imports across Scandinavia. Farming technology nearly identical to the technologies used in Francia and Britain, suddenly appear in the archeological record around the midpoint of the Viking Age. It is proposed that those Scandinavians who returned from raiding brought home farming technologies from the areas they raided. This also means that Vikings undoubtedly did not always massacre everyone in sight. To have learned about the technologies and how they worked, the Vikings would have had to communicate with the owners of that technology and worked with them to familiarize themselves with its uses. Curiosity, it appears, reigned among the Vikings whose interests were truly to better themselves.

Why then, if Vikings were so interested in learning, did they sack and pillage instead of peacefully trading? Simply put, the Christian Empire of Charlemagne forced their hand. Not only did Charlemagne threaten the Danes on their border, but he denied trade to non-Christians, trade which the Scandinavians relied upon. The violence perpetrated by the Christian Empire undoubtedly influenced the Vikings‘ foreign policy. It might even be said that after the incident on the Elbe (see Why Did the Viking Age Begin?) the Vikings may have assumed that Christians would be violent, and so they treated them accordingly. We must remember that this was an age of violence. All of Europe experienced a period of horrific and constant warfare in the vacuum left by the Romans. Because the only people who could leave a record of the Vikings were Christians, the Vikings fell victim to an ever present and applicable historical phenomena: propaganda.

April 2, 2014

What Started the Viking Age?

We know what we know about the Viking Age primarily from two sources: writings and archeological finds. The writings are all written by Christian sources – particularly, monks – who unfairly misrepresent the Vikings because they were the primary victims of the raids. Early in the Viking Age, the focus of the Scandinavian pirates in Western Europe remained fixed on coastal monasteries. Later, the Vikings would attack further inland, but the initial violence (A.D. 793-835) occurred peripherally. The Christians blamed themselves for angering their god. Historians have several hypotheses on what began the Viking Age. Most famous of the hypotheses lies in the climatic changes of the early middle ages which warmed the weather in all of Europe and caused a large population growth unusual for Scandinavia. Most historians draw on a combination of several hypotheses, each a part in the larger picture. While several factors contributed the initial raids, what event acted as the catalyst for centuries of attacks?

A little known series of events in the late 8th century involving the Franks and the Saxons may have sparked the Viking Age in the same way the assassination of Franz Ferdinand sparked World War I. The conditions for the Viking Age were all in place — warm weather, larger population, naval advances, technology advances, and a deep hatred for the Christians in the south. What event, then, caused the launch of thousands of ships westward? In 792 A.D. Emperor Charlemagne (yes, the one credited with inventing public schools) was just finishing his conquest of modern day Poland, as well as northern Germany up to the Danevirke, a barrier build along the southern border of Denmark to repel the germanic tribes. Charlemagne believed it was his duty to spread Christianity across the known world, and he did so through conquest. One of his more notorious exploits took place along the Danevirke in sight of the Danes who watched in horror as the Franks defeated the Saxons. The Franks took 3000 prisoners. Charlemagne ordered the Saxons be baptized in the nearby Elbe River where the Franks dunked the Saxons under water, recited their benedictions, and held them underwater until they drowned. A few Saxons undoubtedly escaped and explained their horrific tale to the Danes who kept in close contact with the Norwegians.

How does this event play into the Viking Age? At Lindisfarne in 793 A.D., the first raid on a monastery, the Vikings dragged many of the priests to the beach and drowned them under the waves. This act is viewed by many historians as symbolic of the raiders’ acknowledgement of the threat of warmongering Christianity on their lands. In essence, the first raid was a retaliation for the aggressive acts of the Franks. It is therefore appropriate to say, after so many years of misconception and misrepresentation, that the Vikings were in reality no more violent than their southern neighbors. It was an age of violence.

April 1, 2014

The Norse Gods Were Mortal

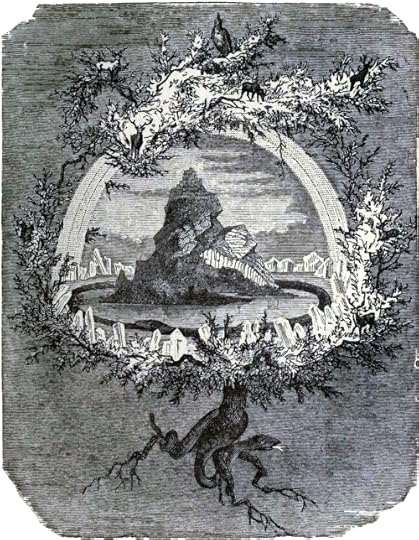

DID YOU KNOW that Norse Mythology is rather peculiar in the fact that their pantheon is mortal? Indeed, the gods of the Norse were not destined to live forever, unlike their Greek and Roman counterparts. In fact, the myths we draw from several sagas make reference to a war at the beginning of time between the Aesir – or gods- and the Vanir, an advanced race equally powerful to the Aesir. The war between the Aesir and Vanir was terribly bloody, and the fighting ended in a stalemate. Both sides recognized the futility of their efforts and met to discuss a peaceful settlement. To ensure lasting peace, the Vanir and Aesir agreed to an exchange of prisoners: two Vanir would join the Aesir, and two Aesir would join the Vanir. Many details on how these people were chosen follow, but the important aspect of this myth to remember is that the gods were mortal and dying in battle against a foe of equal strength. This idea permeated across the Scnadinavian world, and the Vikings recognized that although powerful, their gods were not invincible. The famous Ragnarok is another example of this insofar as all the gods of the Norse pantheon die in a cataclysmic battle with the forces of Jotunheim (land of the giants) and other forces of evil only to be survived by two gods whose purpose in life will be to repopulate the Norse pantheon. Interestingly, the Vanir are not mentioned in Ragnarok, and it is thus assumed that they have no stake or interest in the troubles of the Aesir. Therefore, it was also recognized that there existed realms outside the great ash Yggdrasil (pictured above) with problems of their own. In other words, the Vikings envisioned a boundless universe centuries before anyone else.

March 28, 2014

The Line of His People now on Nook!

The Line of His People now on Nook!

The Line of His People, a Viking epic set in Viking Age France, is now available through Barnes and Noble’s Nook! Enjoy!

“Vikings” Episode 5 Honors Viking Age Women

The questions I believe will be on everyone’s mind after the last episode of the History Channel’s Vikings will surely revolve around the role of women in Viking Age Scandinavian society. What we know about women in the Viking Age comes from two sources: written sources and archeological finds. The History Channel has proposed that women actively participated in the warrior culture of the day. While this idea is rooted in some prominent theoretical historical models, there exists no concrete evidence to show that this was the case.

First, we should examine the archeological evidence for the prominence of a woman’s role in Scandinavian society. Prior to doing so, it should be stated that the Vikings had two distinct classes of people; there were those who were slaves and those who were free. This distinction plays an important part in understanding how women lived in the Viking Age. Slaves, of course, had few privileges, and so for the purposes of this analysis we shall only examine free women. Archeologically, the most intriguing find to date resides in a museum in Norway. Discovered in the early 20th century, the Osberg ship contained a wealth of physical objects which have contributed greatly to our understanding of Viking Age society. Within the ship were the remains of a prominent female figure, currently thought to perhaps even be the mother of Halfdan the Black, grandfather of the first king of Norway. With her body archeologists found a vast array of possessions, including four decapitated horses and a slave, all of which would have once belonged to the honored person in the burial*. No weapons or shields were found near the body, although a few objects resembling daggers and small axes were discovered. Nothing in the burial pointed to the woman being a warrior. This is important because from the male perspective only free men had the privilege to fight. It therefore can also be assumed that the same would have been true of women if the privilege of fighting was theirs. Yet, free women tended to choose not to. No warrior woman has ever been given the honor of a proper burial that we have found.

Written sources of course include Snorri Sturlsson, Adam of Bremmen, and Bernard the Chronicler. According to Snorri, women in Viking Age Scandinavia played tremendously important roles in society. Women in the household had defined roles in knitting and cooking, but also in managing thralls (slaves) and running the farm. If her husband left for war or raiding, the woman took the role of defender of the land and would have taken up arms to defend that land if attacked. Upon a warrior’s death, his land and belongings went to his wife who had no real obligation to remarry, and therefore could, if she so pleased, take over her late husband’s role as the head of household which ostensibly would have included fighting. If a warrior and his wife died without a male heir, the land and property passed to the eldest child regardless of gender. More interestingly, the marriage ceremonies of the Vikings set the precedent for this system. In marriage, the man and woman exchanged dowries (yes, the same as we know of today). At the conclusion of the ceremony, the woman received both dowries to protect them, and all the lands of the man passed to the defender, the wife. Free women would likely have prepared themselves to fight to defend their homes.

Women did not, however, travel on raids or fight in large scale wars that we know of for there exists no evidence, literary or archeological, to prove it; although it should be noted that we cannot disprove that women may have fought in battle with the men and therefore History Channel is not wrong to include women in the fighting (in fact, it’s awesome of them do have done so). I appreciate the History Channel’s inclusion of the fact that women held a higher place in pagan society than in Christian society. This we do know was true. Women in Christendom were considered the property of their husbands. King Ecbert made mention of this at the beginning of episode five. It has been unpopular in the past to acknowledge this historical fact simply because the Christian world has not particularly enjoyed admitting to its faults. After the christianization of Scandinavia, women lost their prominent places in society and became subservient to men. Thus, the true Viking Age had ended.

*Wondering why the ship wasn’t burned? See the article “Did the Vikings Burn Their Ships?” at cjadrien.com

Love the VIKINGS? Check out The Line of His People, an action packed novel about the Vikings in France, and the wars of Jutland (Denmark). Find it here.