C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 19

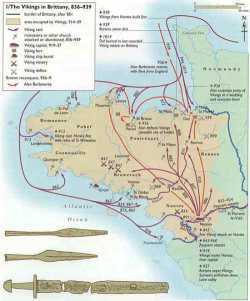

June 4, 2015

Three Common Misconceptions About the Vikings

“A Raid Under Olaf”

“A Raid Under Olaf”1. They were more violent.

Yes, they were violent, but no more violent than any other people at the time. It was an age of violence. In fact, the most violent regime to emerge from the the vacuum left behind by the Roman Empire were the Carolingians who conquered most of continental Europe with the intent to forcibly convert all pagan tribes to Christianity and to slaughter all who resisted. So effective were their campaigns that there wasn’t an army in the world who dared face them at the height of their power under Charlemagne, not even the Vikings. Not until the death of Charlemagne and the emergence of constant warring between his sons over inheritance did larger scale Viking raids begin in Carolingian lands (France/Germany/Poland).

Carolingian Empire

Carolingian Empire

2. They were christianized quickly.

The Christianization of Scandinavia did not occur overnight. The first monarch from any Scandinavian territory to convert was Harlad-Klak of Jutland who did so only to rally support from the Carolingians to help him in his claim to the throne of Denmark in around 815 A.D. Not until the mid 11th Century can we say that Christianity was prevalent among the Vikings, and pockets of paganism survived well into the medieval period (1066-1492).

Medieval Scandinavia

Medieval Scandinavia

3. They were one people.

When we use the word Viking we really do a disservice to the memory of Viking Age Scandinavians. It is a blanket term that is used to apply to anyone who lived and left Scandinavia (Denmark, Norway, Sweden) between the years 790 A.D. and 1066 A.D. They were not, however, as unified a group as we remember them today. The period immediately preceding the Viking Age was a time when settlements in Scandinavia were relatively isolated from one another, except for trade. These settlements had their own traditions, often owed allegiance to differing deities, and developed in parallel with, but separated from, other settlements. By the Viking Age, there were many groups who differed from one another tremendously. For example, a Norwegian from Vestfold may have differed as much from a Swede from Uppsala as he would have from a Saxon from Saxony. Yet today we make a stark distinction between Saxons and Vikings because the differences between them are generally recognized. Much like Scandinavia today, there were linguistic and cultural variations between the people of the region—differences which endure to this day.

For Email Marketing you can trust.

May 27, 2015

Muslim Travelers to the Viking World

Perhaps some of the most intriguing sources about Viking Age Scandinavians to date are chronicles written by Muslim travelers. In the days of the Great Caliphs and the Umayyads, Muslims were among the most prolific travelers in the known world. These explorers encountered all manner of peoples throughout Europe, including the Vikings. Two among them, Ibn Fadlan and Al-Gazhal, explored two worlds apart only to find the same phenomena, yet came away with opposing observations. Ibn Fadlan explored eastward and found the Rus sailing up rivers in the eastern steppes. Al-Gazhal is thought to have traveled as far as Ireland where the Norse had begun to aggressively build coastal colonies. What each observed differed greatly, which has helped scholars over the years to conclude that Scandinavians themselves at the time varied greatly in customs and culture.

Ibn Fadlan:

The Arab chronicler Ibn Fadlan, who encountered the Rus along the Volga River, observed his hosts for several days. One of the most remembered passages from his writings pertains to the Rus’ unusual grooming habits:

“Every day they must wash their faces and heads and this they do in the dirtiest and filthiest fashion possible: to wit, every morning a girl servant brings a great basin of water; she offers this to her master and he washes his hands and face and his hair — he washes it and combs it out with a comb in the water; then he blows his nose and spits into the basin. When he has finished, the servant carries the basin to the next person, who does likewise. She carries the basin thus to all the household in turn, and each blows his nose, spits, and washes his face and hair in it.”

The grooming habits of the Rus were not Ibn-Fadlan’s only observations. Indeed, he observed their funeral rituals as well and has shed light on what may possibly have been a practice among Scandinavians: ship burning. However, his account is to date the only textual evidence for the burning of ships during a Viking funeral.

Ibn-Fadlan characterizes the Rus as a backward, barbaric people, unclean and brutal in their ways. His account has led many scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries to conclude that the Noble Savage view of the Vikings was at least in part correct. This of course is currently being revised.

Al-Gazhal:

In the 9th Century a Moorish ambassador named al-Ghazal set sail for foreign lands to study a people called the Majus. His account tells of his voyage across the ocean to a splendid island described as having lush, flowering plants and abundant streams leading to the ocean. For years historians struggled to gather consensus on who these Majus may have been, but more recently it has become accepted that they were indeed the Vikings. Unfortunately, the consensus ends there. Some scholars believe the embassy of al-Ghazal to have taken place in Denmark, whereas others propose he had visited the court of Turgeis, a powerful warlord who ruled over much of Ireland. His account is compelling and offers a tremendous volume of information about the Majus many scholars believe no chronicler of the time could have fabricated.

The source for al-Ghazal’s embassy to Ireland is a document produced by Abu-l-Kattab-Umar-ibn-al-Hasan-ibn-Dihya, who was born in Valencia in Andalucia, about 1159 A.D. The facts and anecdotes in the story were derived from Tammam-ibn-Alqama, vizier under three consecutive amirs in Andalucia during the ninth century who died in 896. Tammam-ibn-Alqama had allegedly learned the details directly from al-Ghazal and his companions. The only manuscript of ibn-Dihya’s work was acquired by the British Museum in 1866. It is titled Al-mutrib min ashar ahli’l Maghrib, which translates to An amusing book from poetical works of the Maghreb.

Contrary to his contemporary from Bagdad, al-Gazhal characterizes the Majus has highly civilized people with many shared customs. Interestingly enough, one of those shared customs happened to be grooming. During his stay in the warlord’s court, he spent a great deal of time with the warlord’s wife who made it her mission to teach her guest about her people’s customs. Evidently she had a profound effect on him.

Additional Note

We must remember that the Vikings who left Scandinavia were highly adaptable, as noted in several of my previous articles. Within a few short generations, the Vikings who settled foreign lands became very different people than their forebears who first arrived in those lands. It is therefore no stretch of the imagination to think that the peoples al-Gazhal and Ibn Fadlan encountered were in fact very different from one another, and this notion is reinforced in several key places in their accounts. Although today both populations of Norse are labeled under the same name, Vikings, they were not in fact as homogenous a society as previously thought.

For Email Marketing you can trust.

May 22, 2015

The Vikings: Even Their Poop Is Interesting

The Lloyds Bank Coprolite

The Lloyds Bank Coprolite

Archeology has done wonders to expound many of the mysteries surrounding Scandinavian culture of the Viking Age. Scientists have found pieces of armor, leather, ingots, a helmet, swords, axes, whole ships and…poop. Contrary to what you may think, feces is an incredibly important and informative find. In fact, any archeologist worth their salt will tell you that the most exciting finds for them are cesspits, because societies leave massive amounts of information about themselves behind in their trash.

Luckily for archeologists who study the Vikings, they found one such specimen buried beneath the city of York, England in 1972. While digging during the construction of what was to become a branch of Lloyds Bank, workers found a variety of fossilized artifacts. Among them was a seven inch long coprolite (the scientific word for fossilized poop) deposited there during the 9th century. Scientists aptly named the artifact the Lloyds Bank Coprolite, and its finding has helped to shape our understanding of the Norse invaders of England from 1000 years ago.

Paleoscatologists—those who study fossilized poop (yes, you can do this for a living if you want to)—scoured over the coprolite and found that the man who had left behind this magnificent piece of history had a diet consisting mostly of meats and breads. They also found parasitic eggs, indicating that this poor warrior from Scandinavia had to put up with worms as well as the rain.

Paleoscatologist Andrew Jones, who appraised the coprolite for insurance purposes, made headlines in the Wall Street Journal when he said, “This is the most exciting piece of excrement I’ve ever seen…it’s as valuable as the Crown Jewels.” His assessment of the value of the Lloyds Band coprolite was certainly blown out of proportion, but then again we can clearly see from his choice of profession that he was unashamedly biased.

On a more serious note, such finds are often not widely covered due to the vulgar nature we associate with such things in our society. Yet, there is much to learn from our ancestors’ waste, and in fact it may be the key to solving many more mysteries in years to come.

The Line of His People, my debut novel, has recently been rereleased as a second edition on Kindle and is FREE to download until Monday, May 25th worldwide. Download your copy today!

Click to Download

Click to DownloadMay 19, 2015

The Reindeer Antler Comb That Is Rewriting History

Viking Age comb made from Reindeer Antler

Viking Age comb made from Reindeer AntlerVikings have made the headlines this week across the globe after a surprising announcement from scholars at the University of York, in the U.K. Researchers claim they have found evidence that the Viking Age may have begun long before the academically accepted date of 793—the sack of Lindisfarne. According to researchers, they have found deer antlers fashioned into various tools, most notably a comb, which date to as early as 725 A.D. These artifacts were uncovered in the port town of Ribe, in Denmark, and indicate strong trade ties between the Danes and the Norwegians far earlier than previously thought.

Will this discovery rewrite history? It will certainly alter previous notions of the development of the seafaring culture in Scandinavia. But the demarkation of the start of the Viking Age is not likely to change. While trade was an important factor in the launch of the Viking Age, scholars have used the attack on Lindisfarne as the official start of the period because of its proximity to several concurring events, as well as its importance to the Christian world at the time. Setting a date for the start if the Viking Age is difficult precisely because if one only looks at a singular cause, such as violence, trade, climate change, politics, among others, the dates will vary tremendously. The first attack on Christendom was not in fact Lindisfarne. Another raid, mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, tells of an unfortunate encounter a few years prior to Lindisfarne in which a local official in Britain was murdered for insisting on imposing a tax on Scandinavian traders. Raids in Frisia (modern day Netherlands) began as early as the 770’s, as noted by one of Charlemagne’s scholars, Alcuin. Now we have evidence that the Vikings had begun traveling for trade as early as the 720’s. What makes Lindisfarne the best candidate for the start of the Viking Age is that it was the singular most powerful event that brought the Scandinavian raids into the public consciousness of the world at the time. Monarchs, and the people they ruled, became cognizant of the threat posed by the raids most keenly after 793 A.D.

With technicalities aside, the news of the finds in Ribe are of course tremendously exciting for scholars in the field of Scandinavian studies. The finds raise more questions than they answer, but at least we have now confirmed what scholars have theorized for several decades: the Vikings were traveling the world as merchants long before they began to raid. This reinforces several leading theories on why the Viking Age began. Traditionally, scholars blamed a rising population and a changing climate for the exodus of the young male population from the North. However, competing theories have suggested that the massacre on the Elbe (read about it HERE) and the closing of ports to non-Christians by Charlemagne may have contributed to the increasing violence carried out by the Vikings. If they had been trading with the South as early as 725, it now stands to reason that the Danes and Norwegians had grown dependent on foreign trade for much of their livelihood, and closing off trade would have brought about immediate economic woes and later…very well known history.

Ribe, the location where the Reindeer Antler was found, is one of the oldest towns in Europe, thought to have been founded in the early 9th Century. The finds are much more a rewriting of their history than anything else, as they indicate the town had its beginnings much earlier than previously thought. Today it is the sight of an extraordinary Viking museum. You can visit their official page HERE.

In my Kindred of the Sea series, my protagonist Abriel visits Ribe in the first two installments. He participates in the civil war of Jutland in the 810’s on behalf of Horik I, and later he returns to Ribe to collect on an old debt and fights a rogue band of Vikings who attempt to pillage the town. Ribe was an important and wealthy trade center in the Viking Age, and as such was occasionally the victim of the same raids which had enriched it.

The second edition of my first novel is out and FREE right now on Kindle. Download it today!

May 15, 2015

The Most Ignored Viking Destination in History

When thinking of the Vikings, most will think firstly of their exploits in England. To my chagrin, this also happens to be the focus of nearly every plot line of films, miniseries, and documentaries with a historical theme revolving around the Vikings. Authors of historical fiction such as Bernard Cornwell, Giles Kristian, and Robert Low all center on England as the hot zone for Viking activity. This is no surprise considering all of these authors are British, and the largest reading audience in the world is anglophone. The trend is not necessarily bad—Viking Age England was an interesting place. But the Vikings did not stay in England. In fact, England was a tiny chapter in an otherwise massive historical volume covering interactions in lands from Byzantium to Ireland. The most ignored area affected by the Vikings, in my opinion, is likely one you’ve never heard of—the region of Vendée in France.

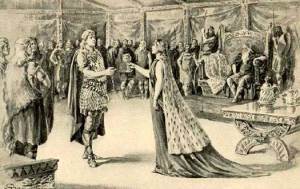

Nominoë swearing vengeance on the Emperor for the death of his emissary.

Nominoë swearing vengeance on the Emperor for the death of his emissary.

During the Viking Age, the region of Vendée did not exist by that name. It was instead referred to as the Breton March. The Frankish Empire struggled repeatedly to keep the impetuous and fiercely independent Bretons (of Brittany) under their rule, and found themselves frequently embroiled in violent revolts. Charlemagne managed to keep the Bretons happy for a time, but his son Louis had little luck with them. Thus they set up what we might consider today to have been a neutral zone—a march that neither side crossed unless to initiate war. In the 820’s, the Breton leader Wihomarc led a successful revolt for several years against the Franks until he was eventually killed. His successor, Nominoë, continued the revolt and eventually broke away from the empire successfully. His timing could not have been worse.

Just as Brittany gained its independence, the Vikings began more aggressive incursions into the region, leading to a series of military and political catastrophes that plunged the entire region into chaos. In 847, the Vikings initiated a mainland invasion, claiming massive swaths of Breton lands for themselves, and brokering a deal with the Breton leader Salomon to keep them. There the Vikings stayed for nearly seven decades, during which time they conquered the city of Nantes, helped the Normans to seize more lands from the Franks, helped the Franks fend off the Normans, and bankrupted an entire province of the Frankish Empire. Not until the Breton reconquest of the early 10th century under a leader by the name of Alain Barbe-Torte was the city of Nantes liberated from occupation, and the region of Brittany restored to its former independence.

The tale of the Vikings in Brittany is one rife with all the elements that would make a good Game of Thrones episode, with assassinations, botched marriages, coups, and betrayals. It was even the first stop of the Moorish emissary Al-Ghazal on his way to visit the Northmen in Ireland. Hastein, supposed son of Rangnar Lodbrok, earned his reputation as the scourge of the Loire and Somme and made a home for himself in the Vendée for a time. Unfortunately, this century-long history is seldom acknowledged in the anglophone world mostly because all of the scholarly work pertaining to the subject is in French.

My Kindred of the Sea series delves into the history of the Viking invasions of Brittany. The first volume, The Line of His People, introduces the Vikings to the region, and the planned future of the series (totaling 9 books in all) will follow them until the reconquest of Alain Barbe-Torte. I hope that through my efforts, I am able to shed some light on, and increase interest in the region and its history.

My Kindred of the Sea series delves into the history of the Viking invasions of Brittany. The first volume, The Line of His People, introduces the Vikings to the region, and the planned future of the series (totaling 9 books in all) will follow them until the reconquest of Alain Barbe-Torte. I hope that through my efforts, I am able to shed some light on, and increase interest in the region and its history.

This month, the first novel in the series will be re-released as a second revised edition. The first week it is available on kindle, it will be free to download! If you’d like to be notified of the release SIGN UP FOR MY NEWSLETTER.

May 4, 2015

3 Viking Inventions We Use Today

The Vikings invented a great many things during their heyday, but not many have survived the test of time. A few inventions, however, have continued well into the modern era, and indeed contributed significantly to our way of life. While the Vikings may not have been the first to invent some of the following, the modern versions of these inventions made it into our daily life because of them.

The Bristled Comb

Archeological digs have turned up bristled combs with varying tooth width. While similar inventions exist in other cultures across the globe, the Viking model is the inspiration for the Western incarnation of the comb. These would have been used to quickly groom facial hair, and brushes were used to groom head hair in both men and women.

Skis

Again, various forms of skis have surfaced elsewhere in the world, but the modern Western tradition of skiing comes to us directly from the Vikings. The word “ski” is a derivative of the Old Norse word of the same meaning, “skíð”.

Fines

Contrary to their Frankish and Saxon neighbors, the Vikings imposed fines on those who broke the law. This was because they wanted to prevent blood feuds, a cultural vestige of their Germanic neighbors in which blood was answered in blood. Instead, Scandinavians set up trials at communal assemblies called Things, and decided on appropriate compensation to be paid to the victims. This tradition was imported to England and France by the Normans (Danes) who imposed fines on those who broke the law rather than outright slay them. Of course there were exceptions, and capital punishment was always an option. While the Middle Ages certainly saw a reprieve in the policy of imposing fines, it became commonplace once again in the later period. Fines had existed elsewhere in the world prior to the Viking Age, but its modern use comes to us from the Vikings.

April 30, 2015

Powerplay: A Viking Woman’s Triumph Over Her Abusive Husband

A woodcarving from the Saga of Halfdan the Black

Viking women were strong. Their culture allowed them more freedom and social mobility than other societies in their day, and more responsibility was given to them in terms of the ownership and defense of the land. Yet often the women were, like their Christian neighbors, wronged by men; abused by husbands who regarded their wives as trophies in war. But the Vikings have many tales cautioning such men from doing harm to women. In particular, the Ynglinga Saga offers a poignant tale of caution in which one woman triumphed over her husband in a power play worthy of Game of Thrones.

It begins with an ambitious young man named Gudrød (also known as Guthröth) who inherited a petty kingdom in Norway around the turn of the century in 800 A.D. His father, Halfdan the Generous, had been a fair, albeit unassertive ruler who had spent most of his life raiding far-off lands. He died upon returning home from such an expedition from a “malady” and was buried in a mound at a place called Borró. Upon ascending the throne, his son Gudrød began immediately setting into motion his ambitious plans. He first married a girl named Alfhild, daughter of King Alfar of Alfheim. Through this marriage, Gudrød gained control of “half of Vingulmark” which is presumed to be a rather significant swath of land in the Oslofjord. Together they had a child, Olaf, and shortly after his birth Alfhild died. There is no mention as to the facts surrounding her death—perhaps it was another malady, perhaps murder. Gudrød certainly had the motive for murder. No sooner as she had died, he began negotiating with king Harald Granraude (the Red Beard) to marry his daughter, Asa, and in so doing acquire more land in the Oslofjord. Harald refused this offer.

Harald’s refusal gave Gudrød precisely the excuse he needed to initiate war with his neighbors. He attacked King Harald in a surprise assault at night and killed both Harald and his son Gyrd. He kidnapped Asa, forced her into marriage, and within a short time they had a son named Halfdan (later to be know as Halfdan the Black, who father Harald Fairhair, first king of Norway), who was presumably the product of repeated raping. But the new queen was displeased with her treatment with her new husband. In fact, she hated him for what he had done.

During an evening banquet at a neighboring farm, Gudrød drank himself into a stupor and stumbled to the edge of the water in the fjord to relieve himself. He was struck through the chest with a lance and “stumbling fell by Stiflu Sound.” When his men investigated the murder, they found it had been committed by Asa’s servant, and when asked about her involvement she, “did [not] conceal that is was done at her instigation.”

Gudrød’s men could not by law exact revenge on Asa, for she had not done the act of killing her husband. The servant, it is written, was killed on the spot. Asa returned to her father’s lands to raise her son and established herself as the ruler of those lands. Gudrød’s eldest son, Olaf, managed Gudrød’s lands until Halfdan came of age.

In the end, Asa triumphed over her husband. She had him killed with no consequence to herself, and lived in peace as ruler in her native lands. She raised a son who later consolidated his father’s lands as well as defeated his brother’s enemies to create a unified kingdom of Vestfold.

Asa’s power play is a central plot element in the novel The Line of His People.

For more on the Ynglinga Saga, you can read it HERE.

April 27, 2015

Shield Maidens: A Modern Fantasy?

Recently I’ve read a slough of articles from various sites stating that shield maidens were much more common than previously thought. Their arguments are based on not-so-recent findings using genetic testing correlated with archeological and textual evidence. Some articles go so far as to claim that shield maidens comprised up to 50% of those who left Scandinavia in search of raiding lands. What I see arising is a new mythology surrounding the shield maiden, one based in wishful thinking, but not based on an apt interpretation of new research.

First, the evidence: several recent articles shared around social media have sited THIS ARTICLE as the basis for their claims. In it, researchers found that up to 50% of Scandinavian migrants (not warriors) were women. From this article, however, many are seeing a fantastical revelation—they are seeing shield maidens. Unfortunately, the fact that genetic tests have revealed half of Norse migrants were female does not automatically or intrinsically indicate that these women were warriors by trade. All it really means is that when the Norse set out to colonize new lands, they recognized the need to bring a viable breeding population for the settlement to survive.

Contrary to the popularized notion that the Vikings raped their way through Europe, they likely would have been culturally disinclined to interbreed with indigenous populations of the new lands they settled. Certainly there was interbreeding going on—particularly in England where predominantly (if not entirely) male armies fulfilled their carnal desires on helpless women they captured. But in areas such as Dublin, Wessex, Cork, Limerick, Normandy, Iceland, even Scotland, Norse settlers, in my opinion, would have preferred their own women to any others for the purpose of colonization. Indigenous populations likewise would have not been inclined to intermix with settlers. On a similar note, Men were not the only victims of the changing climate, political strife, and upheavals that launched the Viking Age. Therefore, those who sought to leave and build new homes in new lands did so as a community of settlers rather than a raggedy band of marauders who simply refused to leave.

So, how common were shield maidens? The simple answer is we do not know. No one knows, and no one is entirely certain if shield maidens were an actual phenomena of the time, or instead the invention of the 12th and 13th century writings about them (specifically in the sagas by Snorri), and later the fantastical creation of the 19th Century’s romantic movement. There were no doubt brave Norse women, as there have been brave women in every culture in history. But I do not think, based on all the research that I have done, that the Vikings would have sent many women into battle considering their value to the community (i.e. procreation). Another factor that is often overlooked in today’s society is sexual dimorphism. This poses a tremendous problem to the idea that Norse women readily participated in raiding and major battles. By the end of puberty, a male human will (on average) possess twice the strength of a female human. This fact would have made warfare—especially hand to hand combat—a most precarious and dangerous venture for women of the day. In today’s world, with our advances in technology and weaponry, women can for the first time in history participate in major conflicts as soldiers. But prior to these advances, and prior to the very recent movement for women’s equality, the world was undeniably patriarchal, even in Pagan Scandinavia.

Therefore, to think that Norse women were actively engaged in warfare is, for now, a fantasy. Sure, there were likely exceptions to the rule, and I’ve written about them before, but to believe that half of all Viking warriors were women is not good history. It’s fiction.

Enjoy reading about the Vikings? Buy my novel:

April 20, 2015

The Greatest Viking

There are many famed warriors from the Viking Age who lived up successfully to the the reputation of their people, but perhaps none so much as Hastein, supposed son of Ragnar Lodbrok (but not likely), and scourge of the Somme and Loire. His life was lived for adventure, and although he did not carve out large swaths of territory for himself as some others had done, he built an enduring reputation for himself as a man of great prowess, largesse, and cunning.

Hastein’s story begins, as many in the Viking Age do, ambiguously. We do not know for certain who his parents were, although it is suggested in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that he was a son of Ragnar Lodbrok. The Chronicle also suggests that he was a Dane, although that too is difficult to verify. His first raid of notoriety was that of the sack of Nantes in 843 A.D. in which he is named in the Annales D’Angoulême as being among the Vestfaldingi, or men of Vestfold. The sack of Nantes was a cataclysmic event which sent ripples throughout the Frankish Empire and marked the beginning of more aggressive Norse incursions.

Hastein was still a young man at this time, and raided with other companies for several years thereafter until he was able to put together his own expedition to explore lands not previously explored by his kin. In 859 with the help of Bjorn Ironside, another supposed son of Ragnar Lodbrok—although the two are not associated as brothers in primary sources—Hastein sailed to Spain where he hoped to gain fame and fortune pillaging the Moors. At first the expedition did not bode well. The Asturians of Northern Spain successfully fought them off, forcing the expedition to continue southward without any loot. They successfully pillaged coastal settlements until they sacked Cordoba, then continued into the Mediterranean Basin.

Hastein was of course ambitious and sought to sack Rome itself. Unfortunately, the walls of the city were too tall and well fortified. Thus he hatched one of the more notorious plans to take the city by creating a ruse to trick the “naïve” Christians. They arrived at the city and sent a messenger to inform the bishop that their leader had been mortally wounded and, in his dying moments, wished to be baptized so that he may reach salvation. The bishop took pity on him and organized the ceremony. A day later, the Norsemen returned to the city to inform the bishop that their chieftain had died, and that he had requested to be buried in the city. Again, the bishop took pity on them and organized the funeral. Hastein’s body was placed on a bier and carried by his men into the city. A gathering of noblemen and clergymen joined them to begin the ceremony when Hastein rose from the dead, snatched the sword beside him, and cut down the bishop. His men of course followed suit and slaughtered the Christians.

The ruse had proved successful and the Vikings under Hastein loaded their ships with loot, proud that they had sacked the famed city of Rome. Yet as they sailed from the city, they realized they had made a navigational error. The city they had sacked was not Rome, but rather the smaller city of Luna some two hundred miles north of their intended target. Nevertheless, their ships were filled to the brim with plunder, so Hastein ordered a return to his base on the Loire. As they attempted to sail past Gilbraltar however, the Moors intercepted them with a fleet of ships, destroying a significant portion of Hastein’s fleet. The chieftain survived and returned to his base on the island of Herius (today called Noirmoutier) with twenty ships, a mere third of the ships he had departed with three years earlier.

This Mediterranean voyage lives in infamy as one of the most ambitious and creative expeditions in Viking history. Hastein went on to have a successful career as the scourge of the Somme and Loire rivers, helped to establish the kingdom of Normandy, slew Robert the Strong in the wars of Brittany, and even fought as an opponent of Alfred the Great as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. He eventually disappeared from history around 896 A.D. The conditions surrounding his death remain a mystery. Nevertheless, he left his mark on the world he lived in, and might be considered the most archetypal example of a Viking chieftain and warlord, and perhaps the greatest Viking of them all.

April 10, 2015

The Most Interesting Viking You’ve Never Heard Of

The man considered to have been the first king of Norway, Harald Fairhair, would likely not have succeeded in his rise to power if not for a powerful warlord from northern Norway in the district of Lade. The only source we have for this man is the Heimskringla, but enough information is contained therein to inform us that the men from Lade played an important part in Harald’s rise to Norwegian hegemony. Håkon Grjotgarson, also known as Håkon the rich, helped Harald in many engagements by providing men and money.

The ties between the two men had not been so certain in years prior. Lade was a populous region and had Håkon decided to rally the other leaders in neighboring lands, Harald might not have had the resources or the manpower to overcome them. But as fate would have it, the Earl of Lade chose to offer his allegiance to Harald. As part of the alliance, Håkon was named earl of his district and Harald married Håkon’s daughter Asa. Their alliance swiftly brought the other petty kings of Norway to their knees. Immediately following Håkon’s pledge, Harald won a string of decisive victories and consolidated power, making him the first king of all of Norway.

Why then did Håkon chose to support Harald? The Heimskringla does not say why, but given the political climate of Norway during Harald’s rise to power, it is not too difficult to surmise that Håkon had a great deal to gain in an alliance with him. To stand against the young ruler would have meant years of divisive warfare between Lade and the rest of Norway. With his daughter married to Harald, Håkon’s bloodline would at least carry on in the dynasty, and the ensuing peace meant not having to sacrifice his riches in all out warfare. Additionally, pledging himself outright to the future king would gain him favor in the king’s court, and Håkon likely had a suspicion that Harald would eventually become king whether he stood with or against him.

Read about Håkon in the Heimskringla. (beginning on page 63)