C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 16

September 3, 2016

The Vikings: An English Teacher’s Worst Nightmare?

It is the question parents and teachers alike struggle to answer: why does English break all of its own rules? Children are seldom given satisfying answers. In fact, if modern public schools are any indication, most people simply do not know why English is such a mess because (surprise!) the Viking Age is either entirely absent from, or a mere footnote in, the curriculum. To most, English just is what it is. Therefore the following revelation may be come as a surprise to many.

If you’re an English teacher, you owe a great deal of your daily struggles to the Vikings.

Here is why:

The Vikings visited and pillaged the British Isles beginning as early as the 8th Century A.D. and continued this enriching tradition for several decades. By the mid 9th Century, however, their motives changed from plundering to conquering. They invaded a large portion of England and established a territory called The Danelaw, a period in English history that saw the laws of the Norsemen applied widely to the local population (some have even survived in remote parts to this day). This period in the 9th and 10th Centuries A.D. created a melting pot in which swathes of the invaders’ language assimilated into the proto-English language of the time, the language of the Anglo-Saxons. Vikings from Norway and Denmark left their most enduring legacy in the British Isles through their speech.

In 1066 A.D., the Normans, a group of Francophone Danes (former Vikings) from a region across the channel called Normandy, conquered England under the leadership of William the Conqueror. They imposed a strict legal code called Norman Law, and imposed their own form of corrupted early French on their new subjects, which ultimately further confused things. The French language brought with it many new words and a starkly different grammatical structure. What made the Norman conquest one of the most dramatic events to shape the English language was the Normans’ recognition of the need to legitimize themselves to their subjects. This meant that they learned the local language quickly (as they had done with French), and within only a few generations a new language emerged from the mixture.

As a result of these conquests, the people of the British Isles had many words to say the same thing, and many ways to say it. The language that emerged from the Norman conquest drew upon a combination of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and French. Suddenly, one could use different words for the same thing to be more precise, or to sound more intelligent. Using pigs as an example, the words ‘pig’ and ‘swine’ originated from the Anglo-Saxon language and referred to the animal toiling on the farm, but once it was cooked and served, it was called pork, from the French ‘porc’. Other examples include chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot, sheep/mutton, among many, many others. Because of the Normans’ station in society, Norman French words became associated with the upper class, and Anglo-Saxon words were associated with the lower class (Ex., Intelligent vs smart). That’s why fancier words in English tend to come from French roots. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule.

Grammatically, English experienced several major transformations in this early period. The combination of the more germanic Anglo-Saxon language and latin based French created the beginnings of all the fun grammatical exceptions school children so loathe today. Later there would be another major change at the end of the middle ages known as the Great Vowel Shift, which is responsible for many of the spelling anomalies in the written language and pronunciation differences between similarly constructed words.

English is a tricky language because it borrows from so many sources. Therein also lies its strength: it is arguably one of the most adaptable languages in the world. Its malleability has allowed for today’s major industries to invent entirely new vocabularies to describe their creations, tech being the most obvious benefactor, with science closely behind. This too we owe, in large part, to the Vikings.

August 25, 2016

What Really Started the Viking Age?

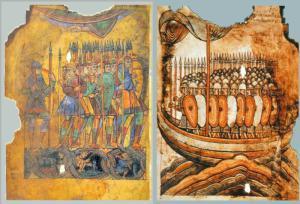

Massacre at Verdun, Saxon Wars

Academics currently stand divided over the precise cause of the first raids by Scandinavians. The leading theory suggests that a combination of overpopulation and a reduction in food due to a brief climatic cooling period forced the Vikings to set sail for new lands. While this is no doubt a part of the broader picture, one may hardly say that it was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. A myriad of socio-economic factors contributed the inevitable exodus of Scandinavians from their homeland, but their appearance in the historical record was certainly abrupt. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes it seem as if the first attack on Lindisfarne had come out of nowhere. What, then, caused the sudden launch of attacks across Christendom? The true source for the beginning of the Viking Age may have been a spat over religious dogma rather than economic incentives.

In the early 8th Century, a brief period of warming gave rise to population growth across the European continent, including Scandinavia. Many parts of the continent prospered and trade increased between previously isolated settlements. Recently uncovered evidence suggests that trade opened up between Scandinavia and Northern Mainland Europe as early as the second decade in the 8th century. This indicates that the Scandinavian maritime tradition must have already been well developed and that population movements may have begun over a century before the great Viking invasions of Britain and Ireland. Trade, it seems, was the force behind the development of their maritime tradition, not warfare.

If trade between Scandinavia and mainland Europe had developed seven decades prior to the accepted beginning of the Viking Age (793 A.D.), the theories behind the causes of Scandinavian expansionism must be reevaluated. The theory behind climate as a chief cause still stands, but in light of trade having been well established, the political landscape of the late 8th century thus becomes a key factor. It is no coincidence, therefore, that the launch of the Viking Age occurred around the time of Charlemagne’s aggressive campaign to christianize the Saxons of Northern Europe.

In 791, Charlemagne, the leading monarch in Christendom, closed all of the ports of the Frankish empire to trade with non-christians (this is mentioned in both Einhard’s biography of Charlemagne and in the Royal Frankish Annals). His goal was to force the Saxons and Frisians to submit to his will and to the church through what we today might consider to be a trade embargo. The Saxon Wars were a bloody, drawn out conflict that proved to be a major thorn in Charlemagne’s side, not least because despite his restrictions on trade, they continued to rebel against him. What he did not see, or could not see, was how economically tied the peoples of Northern Europe were to their Scandinavian neighbors—neighbors who became increasingly reliant on trade to support a population suffering through a series of poor harvests. What Charlemagne had done, in essence, was to cut off Scandinavia’s lifeline.

It is no wonder, therefore, that the first attacks carried out by the Vikings were against monasteries. Although they left no written record to tell us exactly why they attacked holy sites first, it is not a very big leap (although it is still a leap) to conclude that it was, in part, retribution for Charlemagne’s holy war against the pagans and the ensuing economic hardships it caused in Scandinavia. As further evidence of this assertion, we need look no further than the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, which described the events at Lindisfarne in 793 A.D. According to the Chronicle, the Vikings took priests down to the water and drowned them. Some scholars (myself included) believe this was a direct message to the Christians in reference to the massacre of Verdun. Therefore, the wars in Saxony were intrinsically tied to the launching of 3 centuries of raids and colonizations.

In closing, the debate continues. To my readers I must remind you that nothing is certain in Scandinavian studies. We have evidence accompanied by disputed interpretations of that evidence. As a refresher, read my previous post about the true nature of Viking studies. The theory proposed above is but another name in a proverbial hat to be discussed and debated. I encourage conversation. Let me know what you think. Do you agree with my assertion that the catalyst for the beginning of the Viking Age was Charlemagne’s holy war in Saxony? Why or Why not? I look forward to your responses.

May 22, 2016

Vikings: A Culture of Learning

History has falsely remembered the Vikings as brutish, amoral barbarians with no respect for anyone but themselves. What we know of the vikings comes to us primarily from the works of Christian clerics (the only literate people of the Viking Age in Europe) who happened to be the Vikings’ favorite victims. Thus, monastic orders made sure to vilify their foe. Initially, these were the only sources available to scholars of the 19th century who began to piece together the history of the Viking Age. Their early conclusions, steeped in the values and prejudices of the day, have lent to the stereotypical frameworks of the Vikings we have grown accustomed to in literature and the media. In the past twenty years however, the misrepresentation of the people we know today as the Vikings has redressed; new finds and evidences point to a much more cultured and intellectual population. Archeologists, historians, and medievalists now acknowledge that our previous understanding of Scandinavian culture in the early medieval period has classically been incorrect. A more holistic approach to the field has shown us that indeed Viking Age Scandinavians had rich traditions and, most importantly, a central culture of learning.

The Viking invasion of Brittany

The culture of learning in Viking Age Scandinavia begins with a myth. Norse mythology was central to the establishment of Scandinavian institutions and power structures as well as cultural life and social expectations. In particular, the myth surrounding the leader of the Aesir, Odin, resonates profoundly even today among many who ascribe to Norse paganism. Odin, creator of men, obsessed over knowledge. He prided himself on his ability to learn and to apply that learning to his life. His obsession led him to take extreme measures. In the myth called “Mímisbrunnr” Odin visits a well located beneath the world tree Yggdrasil guarded by a mystical character named Mimir. The water of the well was said to contain great wisdom and knowledge and allow those who drank from it to see the future. Odin desired greatly to take advantage of the wisdom contained therein, but that knowledge came at a price. The well’s guardian asked for one of Odin’s eyes in exchange for one drink. Odin obliged him. His desire for knowledge superseded all other carnal pleasures available to him.

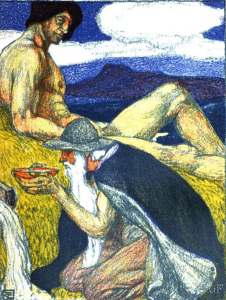

Odin drinking from Mimir’s Well

The myth serves as a counterpoint to the old paradigms of scholarship on Viking Age history. Odin, the most beloved deity in the Norse pantheon, strived for knowledge. Any devotees to his worship would assuredly have strived to emulate this most prominent character trait. As it turns out, archeology has provided the evidence we need to prove this cultural attribute. Evidently, the Vikings brought home much more than just loot. One example is the finding of a sword, the Ulfberht, whose construction required a technology not available to most of Europe until hundreds of years later. Analysis of the metals in the sword have shown the steel’s purity to be nearly that of crucible steel. What does this mean? Simply put, the purity of the steel would have required temperatures higher than any fire made by any blacksmith in Europe at the time to produce. The technology to produce such an artifact tells us that the Norse must have learned the technique elsewhere, likely in the East where Damascus Steel, a close second to crucible steel, was already in production. This import was made possible by the exploits of the Swedish Vikings, known as the Rus, who traveled across the eastern steppes of modern day Russia as far as the Black Sea and the Byzantine Empire (see The Vikings in Georgia?). Trades and cultural exchanges were common, to the extent where an 11th century Arabic silver coin was found in Newfoundland! The vikings, we now know, attained many advances and much wealth as a result of their travels.

recovered Ulfberht

Archeologists have found droves of evidence of technological imports across Scandinavia. Farming technology nearly identical to the technologies used in France and Britain suddenly appear in the archeological record around the midpoint of the Viking Age. It is proposed that those Scandinavians who returned from raiding brought home those technologies from the areas they raided. This also means that the Vikings undoubtedly did not always massacre everyone in sight. To have learned about the technologies and how they worked, they must have communicated with the owners of that technology and worked with them to familiarize themselves with its uses. Curiosity it appears reigned among the Vikings whose interests were, inevitably, to better themselves.

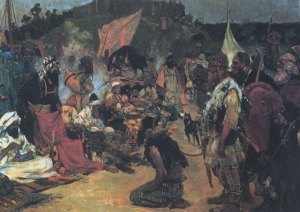

A Viking trade with the Moors

Why, then, if Vikings were so interested in learning did they sack and pillage instead of peacefully trade? One leading theory suggests the Christian Empire of Charlemagne forced their hand. Not only did Charlemagne threaten the Danes on their border, but he denied trade to non-Christians, trade which the Scandinavians relied upon. The violence perpetrated by the Christian empire undoubtedly influenced the Vikings‘ foreign policy. It might even be said that after the incident on the Elbe (see Why Did the Viking Age Begin?) the Vikings may have assumed that Christians were intrinsically violent, and so they treated them accordingly. We must remember that this was an age of violence. All of Europe experienced a period of horrific and constant warfare in the vacuum left by the Romans. Because the only people who could leave a record of the Vikings were Christian clerics, they fell victim to an ever present and applicable historical phenomena: propaganda.

Charlemagne and his Horde.

May 20, 2016

Three Vikings Who Were More Interesting (and Notorious) Than Ragnar Lothbrok

History Channel‘s Ragnar Lothbrok, although remarkable, is a character from legend. There is no telling whether he was real or a fable because there simply no concrete evidence one way or the other. His recent ascension to fame in popular culture is without a doubt a good thing for Norse studies, but now it is time to take a look at those Vikings who we know for sure existed and whose lives were, in fact, more remarkable than the legendary King of cable television.

1.Hastein

A supposed son of Ragnar Lothbrok—although he likely claimed this for prestige, similar to how the nobility in France all claimed lineage to Charlemagne—Hastein lived a life envied by his contemporaries. He began his journey as a relatively unknown warrior who appears in a few mentions beginning in the mid-9th century. His claim to fame was his voyage to the Mediterranean with his brother Bjorn Ironside, and together they sacked Cordoba on their way to the Mediterranean basin. Their fortunes were not consistent, however, and the islamic states of North Africa mounted effective resistance to them. Most notoriously, Hastein helped to sack the city of Luna, which at the time they believed to have been Rome. They tricked the local clergy into believing that their leader had died of pestilence moments after converting to Christianity. The local clergy took pity on him and allowed the Northmen to enter the city to conduct a Christian burial. During the ceremony, Hastein sprang to life, murdered the bishop, and with his men sacked the city (sound familiar?).

Hastein returned to his base on the French coast, an island now known as Noirmoutier, without most of his fleet—they had been ambushed by the Moors at Gibraltar and most of Hastein’s ships sank. Nevertheless, Hastein made a solid career out of raiding the Frankish Empire and earned the hearty reputation of Scourge of the Somme and Loire.

Primary Source authors and documents which attest to Hastein’s life and notoriety:

Dudo of Saint Quentin

William of Jumièges

Annals of St-Bertin

Chronicle of Regino de Prüm

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

2. Leif Eriksson

Born to a father exiled from Iceland for being too violent, Leif undoubtedly lived a difficult childhood. The North Atlantic made for arduous subsistence, even for the Vikings. Due to his father’s reputation, he lived as an exile himself for the most part and did not attempt to make any significant return to Norway. Instead, he became an explorer, one of the most remembered to this day. Based on a rumor, he took ships across the seas in hopes of finding new fertile lands for his people. The rest is all very well known history.

Leif’s legacy helped to shape our view of the Vikings. He helped us to think of them as explorers rather than killers, as adventurers rather than rapists. Most importantly, he planted a seed in the consciousness of Europe, one which reignited in the 15th century and led Europe to global hegemony.

Primary source authors and documents which attest to Leif’s life:

Saga of Erik the Red

The Saga of the Greenlanders

3. Oleg of Novgorod

When discussing the Vikings, the Rus are often forgotten. It seems popular culture has had little trouble romanticizing the Norwegians and Danes who sailed West, but has classically held little interest in those who sailed East. But one of the most influential men of the early medieval period lived there, and his legacy lasted well into the modern era. Oleg began as a regent to the throne of Novgorod whose duty it was to oversee the training of the next monarch, Igor, son of Rurik of Novgorod (yet another fascinating character). During his reign, Oleg consolidated power among the the cities situated along the Dnieper river and eventually conquered the city of Kiev, which he then made his capital. Kiev was of strategic value as it was well placed to launch raids on Constantinople. Following several successful missions, the gentry of the city caved and struck a very favorable trade agreement with Kiev. This trade agreement helped to enrich the city under Oleg, and thrust the polities of Kiev and Novgorod into positions of power. Thus began the early history of the country we know today as Russia.

Primary source authors and documents which attest to Oleg’s life:

The Russian Primary Chronicle

The Novgorod First Chronicle

The Kiev Chronicle (which really only deals with his death and burial)

May 5, 2016

The City the Vikings Sacked Before Paris, and Why It Matters.

**Painting by Édouard Jolin, can be seen in the cathedral of Nantes. Depicts the murdering of bishop St Gohard by the Vikings in 843.

The Vikings loved France. They loved it not because they wanted live there, but because it was full of undefended monasteries and churches filled with valuable treasure. Charlemagne’s Empire was the favored realm of Christendom, and under it the church prospered—and they made themselves rich. Unfortunately for the Vikings, Charlemagne was a keen tactician and an astute politician. His grip on his empire was firm as steel, making the river systems therein nearly impenetrable. Not until his death did the empire he so carefully sewed begin to unravel. His only son, Louis, while not an entirely incompetent ruler, oversaw the partition of the empire that allowed the Vikings to attack.

Charlemagne was lucky. The Franks had not yet adopted the tradition of primogeniture, the passing of a ruler’s lands to the eldest son, which should have forced him to split his empire up among his sons. Louis was Charlemagne’s only legitimate heir (there were, of course, many illegitimate children), making the preparations for his succession quite simple. Louis, however, had already fathered several sons by the time his father died, and he quickly set about making preparations to secure his succession upon his own eventual death.

All was well until Louis fathered a fourth son with his second wife. Per the custom, he began preparations to add his latest heir to his inheritance, an act that incited his other three sons to rebel against him. Thus began the first civil war in the Frankish Empire. Troops were called away from their posts across the land to help fight on one side or the other. The empire’s economy collapsed. For a time, the entire continent seemed to be at war.

In 841 A.D., years of fighting between the factions culminated at the battle of Fontenoy-en-puisane from which emerged the Treaty of Verdun. The treaty effectively split the empire among Louis’ three living sons (alas, poor Pepin died during the fighting). In the West, Charles the Bald inherited a territory roughly corresponding to modern France. His brother Lothaire inherited lands in Italy, and a thin strip all the way to the Baltic via modern day Switzerland and Germany. In the East, Louis the German inherited lands from modern day Germany to modern day Poland. This partition would affect the geo-political makeup of Europe until today.

Following the partition of the empire, the smaller kingdoms therein remained in constant conflict. Until this time, no major outside threat seemed to loom over the Franks, so they continued to ignore the signs that, in retrospect, were a little too obvious. The Vikings had been raiding coastal communities intermittently for decades, but the leadership of the Franks appear to have not acknowledged their increasing boldness. After all, Charlemagne’s defenses had proven an effective deterrent to upriver excursions in the past. What the Franks did not know is that the Vikings had aggressively pushed into the British Isles, including the heavy colonization of Ireland, keeping most of them busy elsewhere. It took only one attack to set into motion a century of invasions in France, invasions which triggered the demise of the Carolingian dynasty.

In 843 A.D. hostilities between the Frankish factions finally ceased. The Empire, now a conglomeration of smaller kingdoms, experienced a brief period of peace. On June 24th, however, it all proverbially went to hell in a hand-basket. In the city of Nantes, nestled along the Loire River in the southern part of the region of Brittany, the festival of Saint John (La Saint Jean, in French) kicked off with the usual festivities: a local fair where merchants and pilgrims gathered to exchange goods and services prior to attending mass in the city’s romanesque cathedral. Seeing as it was a religious holiday, no one ever imagined anything terrible would happen, and so they neglected to post guards at the entrances to the city, and they had left those entrances open. Among the visitors to the city were a great number of hooded men—tradesmen, so the denizens of the city thought. But these men had not arrived at the city to trade. They were scouts. Their mission was to infiltrate the city, perhaps simply to see how easy it might be. Seeing that the city was completely undefended, they revealed themselves as weapon-clad warriors with more malicious intents than to celebrate a Christian saint.

The entire account of this history was recorded in a document called the Annales D’Angoulême, which did not survive to today. It is, however, incorporated into an account written at the end of the 11th century called the Chronique de Nantes (the Nantes Chronicle). Nantes at the time was a well known religious and economic center, a truly rich target for any foreign invader. Its bishop, Gohard, was well known and respected among his peers. The attack itself is a brief passage in the chronicle, and all we may really gleam from it is that the bishop was égorgé, meaning he had his throat slit in front of his audience. News of the sack of Nantes quickly spread across Christendom and is a referenced event in several other chronicles of the time, such as the Annales Bertonni, the works of Adam of Bremen, and several other more obscure writings. At the time, the event was a veritable shock to the Carolingians.

The most important aspect of the attack is that it was the first of its kind. Never before had the Vikings sacked a major settlement in the Carolingian Empire. The attackers, referred to in the Annales D’Angouleme as Vestfaldingi, men from Vestfold, were also not who one might have expected to make such a daring incursion. The fact that the chronicle names the specific kind of Vikings who sacked the city tells us two things: that they were Norwegians, not Danes, and that they had taken the time to introduce themselves to their victims.

We know from numerous other sources that the Danes and the Norwegians had a certain rivalry between them during the Viking Age. While the Danes were far more involved in England than the Norwegians, the Norwegians competed rather effectively with their Danish rivals for lands in Ireland. It is therefore not surprising, although still mostly an educated guess, that the Vikings who sacked Nantes had travelled there from Ireland. Furthermore, it is fairly certain that they boasted of their victory and, according to oral tradition, news of their success would have travelled quite fast indeed across the Viking world.

It was only two years later that the Danes entered the Seine river and sacked Paris. To have done so a few decades earlier would have been suicide. The leaders of the Danes took a major risk by leading as large a fleet as they did up to the walls of Paris. But they already knew the Franks were weaker than before. They knew because of Nantes.

February 22, 2016

The Vikings: Divine Retribution Against the Franks?

The Carolingian Empire was the greatest superpower of its day. It was unmatched by its rivals, and its most famous leader, Charlemagne, was revered by the papacy for his efforts to spread Christianity. At its height, the empire stretched from Spain to Denmark, and from Brittany to Austria. Europe would not see another empire of its size until Napoleon. Under Charlemagne, all seemed well, until his grandsons unravelled everything.

The Carolingian Empire was the greatest superpower of its day. It was unmatched by its rivals, and its most famous leader, Charlemagne, was revered by the papacy for his efforts to spread Christianity. At its height, the empire stretched from Spain to Denmark, and from Brittany to Austria. Europe would not see another empire of its size until Napoleon. Under Charlemagne, all seemed well, until his grandsons unravelled everything.

The Franks had not developed the concept of primogeniture, meaning their lands had to be divided equally amongst all of their sons. Charlemagne was lucky, for he had only one legitimate heir and so his empire remained intact after his death. His son Louis, however, fathered three sons early in his life and was urged to make plans for his succession. He divided the empire among the three, but shortly thereafter he fathered a fourth son by his second wife. He redrafted his will to include his youngest, causing his first three sons to rebel against him. The empire was plunged into a chaotic civil war.

Lying in wait was an enemy who had been unsuccessful in breaching the coastal defenses to the empire under Charlemagne. With the armies of the Franks engaged elsewhere, the Vikings made their most bold advances on major cities that had once been thought untouchable. First Nantes in 843 A.D., then Paris in 845 A.D. From there the Franks suffered disastrous defeats against the Vikings and would not be rid of this new foe for over a century.

The Franks should have seen it coming.

There is a similar narrative from earlier in history that parallels the woes of the Frankish Empire. In the third Century, the Roman Empire experienced many crises, including one in the British Isles that saw many Britons flee into the region of Brittany, in modern day France. Taking advantage of the situation, seaborne raiders pillaged the coasts of the Roman Empire from Normandy to Aquitaine. Their raids further destabilized the region and helped lead to the eventual collapse of Rome’s authority along the Atlantic coast. These raiders were none other than the Franks.

Indeed, the Franks had developed a rich maritime tradition in the Baltic, one which they later abandoned in favor of land-based conquests. Their absence from the baltic region as a powerful seafaring force is arguably what allowed the Vikings to develop their maritime hegemony over the other germanic tribes. Four hundred years after they had helped usher in the demise of an empire, the Franks fell victim to the same style of assault that helped to bring about their own empire’s demise.

Perhaps it was just history repeating itself, or perhaps it was divine retribution.

February 11, 2016

What is a Viking, Really?

Harald Hardrada, Considered to have been the last Viking king

Vikings are a popular topic these days. From football teams, to TV shows, to massive reenactment festivals, Vikings are quickly becoming the next werewolves, vampires, and zombies of popular culture. I wouldn’t be surprised to see a few show up at Comicon…oh wait, they have. But unlike the afore mentioned topics du jour, Vikings were a real thing. They actually existed. So who were the Vikings? What qualifies as being Viking?

It’s all in the name

The word “Viking” is derived from Old Norse. “Vikingr” was a noun used to describe a sea-rover or pirate. It was also used as a verb, as in “to go Viking”, in other words to go raiding. At the time, a “Viking” was a man who left Scandinavia in search of new opportunities (like pillaging) abroad, and it did not describe the region, the times, or most of the people.

As the Viking Age came to a close, so did the word’s usage. It remained dormant for centuries thereafter.

Historians in the 19th Century who began to study the time period roughly between 793 A.D., the attack on Lindisfarne, and 1066 A.D, the Norman invasion of England, picked up the word as a placeholder to describe an approximate time period, the “Viking Age”. They named it as such because the greatest impact on history was done by the raiders, and so their name became synonymous with the most major upheaval in Europe since the Moorish invasions. As historians looked back to Scandinavia to study the culture from whence the Vikings (old usage) came, they made no etymological distinction between them, and so all of Scandinavia became Viking.

Today, the word is commonplace and is used to describe a greater breadth of topics—from internal politics to daily life, confined only by time and an approximate geographic location—rather than just the men who left to raid abroad.

Essentially, the word “Viking” signifies Viking Age Scandinavia, their culture, their history, their artifacts, etc.

There are of course two divergent thoughts when it comes to what is Viking and what is not. Some people are purists and believe the word Viking should only refer to the raiders who left Scandinavia. Others (most of us) accept the evolution of the word in our modern language and use it to describe the rich culture and history of Viking Age Scandinavia, as well as all the fun things they did across Europe at the time. A Viking, therefore, may refer to a farmer who lived in Vingulmark in 820 A.D., or a Jarl who lived in Trondheim in 850 A.D. (that would be Hakón Grjotgarsson), or a raider accompanying the warrior Hastein in the Mediterranean in 859 A.D. To we modern observers peering into the past, they all belong to the same place and time, and thus carry the same name.

February 8, 2016

The Dangerous Duality of Modern Paganism in America

America is a diverse place. Freedom of religion is taken seriously and has led to the world’s most interesting mix of highly individualized belief systems. This is no surprise considering the first migrants to arrive in North America fled religious persecution in their homeland and wished to build new lives for themselves where they could worship whatever god or variation of a god they wanted. America is a place where people are allowed to believe whatever they want to believe, and there are quite literally people who believe in anything and everything—from Bigfoot to Aliens to whatever you can think of, evidence not required.

It should therefore be of no surprise that there are small communities and individuals throughout the country who are reviving the old ways of Norse Paganism. Specifically, these groups of people want to emulate the belief systems of Viking Age Scandinavia. This belief system today goes by a few different names, Asatru being the most well known and accepted. Here I will refer to it as the Modern Pagan movement because of the numerous names that are derived from it. It is a subject near and dear to my heart because of the years I’ve spent devoted to the study of Scandinavian history. The attempt to revive their pagan ways is intrinsically interesting to me. Iceland, for example, is also experiencing a revival of what they call the “old ways” and their new pagan church has made headlines around the world. In an age where the masses are becoming disenfranchised with traditional institutions, this revival is attracting a great deal of attention.

There is much to applaud in this movement. It has ignited interest in history, in the exploration of a distant and foreign culture, and it has encouraged many to find a different path for personal growth. Yet what is most curious about this movement is how different the interpretations of the “old ways” seem to be. There is no consistency in Modern Paganism, but many (and I’ve met a few personally) are militant in how they defend their own particular brand of it. In fact, much of the zealousness demonstrated by mainstream religions has carried over, and there are those who are practicing this new faith with immovable conviction without basis in tradition or dogma. These people have an idealized, almost nostalgic vision of how life used to be in pre-Christian times, but it’s all wrong.

What must be noted is that we know very little of the pre-Christian pagan faiths of Northern Europe. What has survived to today isn’t from tradition but from testimonies written by Christian clerics who examined those religions through a specific cultural lens. After the Christianization of Scandinavia, the pagan traditions were essentially wiped out. Therefore, it is important to understand that, realistically, we know close to nothing about the details surrounding the religion of pre-Christian Scandinavia, and we can never truly know. With this in mind, the Modern Pagan movement begins to take on a more problematic character. It means that most of the practices and beliefs of Modern Pagans are mostly made up. This is a problem because the movement is being used by some for nefarious purposes.

The Modern Pagan movement has a seedy underbelly that is by no means representative of the larger population of believers—but it’s there. It seems that many who would seek to argue for their supremacy over others by virtue of race and heritage have hijacked the Modern Pagan movement and given it a bad name. Because there is no rigid doctrine to refer to, it is difficult to dispel their assertions or to convince those not affiliated with Modern Paganism that such views are incompatible with the faith. No one can say that the Vikings were not racist. We cannot know. So, the presumption will always be that Pagans are racist. To quote the Havamal, “The good is ignored where there is fault.”

On the one hand, there are people who are experiencing tremendous personal growth through the Modern Pagan movement. On the other hand, there are those who are utilizing it for hate. So while it all seems like fun and games, there is an innate danger in the revival of a religion that is mostly fictionalized and is derived from a fixation on heritage. Modern Paganism has left itself open to being hijacked and there really is no defense. If an established religion such as Christianity or Islam cannot weed out radicals, how can a revived religion with no clear structure be immune? Perhaps it is best if we not fool ourselves and stick to the history books. Of course, it’s a free country, so believe what you want. Just remember that free speech doesn’t protect hate.

January 26, 2016

The Vikings: An English Teacher’s Worst Nightmare?

It is the question parents and teachers alike struggle to answer: why does English break all of its own rules? Children are seldom given satisfying answers. In fact, if modern public schools are any indication, most people simply do not know why English is such a mess because (surprise!) the Viking Age is either entirely absent from, or a mere footnote in, the curriculum. To most, English just is what it is. Therefore the following revelation may be come as a surprise to many.

If you’re an English teacher, you owe a great deal of your daily struggles to the Vikings.

Here is why:

The Vikings visited and pillaged the British Isles beginning as early as the 8th Century A.D. and continued this enriching tradition for several decades. By the mid 9th Century, however, their motives changed from plundering to conquering. They invaded a large portion of England and established a territory called The Danelaw, a period in English history that saw the laws of the Norsemen applied widely to the local population (some have even survived in remote parts to this day). This period in the 9th and 10th Centuries A.D. created a melting pot in which swathes of the invaders’ language assimilated into the proto-English language of the time, the language of the Anglo-Saxons. Vikings from Norway and Denmark left their most enduring legacy in the British Isles through their speech.

In 1066 A.D., the Normans, a group of Francophone Danes (former Vikings) from a region across the channel called Normandy, conquered England under the leadership of William the Conqueror. They imposed a strict legal code called Norman Law, and imposed their own form of corrupted early French on their new subjects, which ultimately further confused things. The French language brought with it many new words and a starkly different grammatical structure. What made the Norman conquest one of the most dramatic events to shape the English language was the Normans’ recognition of the need to legitimize themselves to their subjects. This meant that they learned the local language quickly (as they had done with French), and within only a few generations a new language emerged from the mixture.

Suddenly there were many words to say the same thing, and many ways to say it. The language that emerged from the Norman conquest drew upon a combination of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and French. Suddenly, one could use different words for the same thing to be more precise, or to sound more intelligent. Using pigs as an example, the words ‘pig’ and ‘swine’ originated from the Anglo-Saxon language and referred to the animal toiling on the farm, but once it was cooked and served, it was called pork, from the French ‘porc’. Other examples include chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot, sheep/mutton, among many, many others. Because of the Normans’ station in society, Norman French words became associated with the upper class, and Anglo-Saxon words were associated with the lower class (Ex., Intelligent vs smart). That’s why fancier words in English tend to come from French roots. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule.

Grammatically, English experienced several major transformations in this early period. The combination of the more germanic Anglo-Saxon language and latin based French created the beginnings of all the fun grammatical exceptions school children so loathe today. Later there would be another major change at the end of the middle ages known as the Great Vowel Shift, which is responsible for many of the spelling anomalies in the written language and pronunciation differences between similarly constructed words.

English is a tricky language because it borrows from so many sources. Therein also lies its strength: it is arguably one of the most adaptable languages in the world. Its malleability has allowed for today’s major industries to invent entirely new vocabularies to describe their creations, tech being the most obvious benefactor, with science closely behind. This too we owe, in large part, to the Vikings.

January 5, 2016

Long or Short: How Did the Vikings Wear Their Hair?

It should be obvious. Vikings were barbarians, fitting of the description of “Noble Savages” who would have sported long, flowing locks of hair. Or were they?

Recent revisions to Viking history have painted a starkly different picture of what life was like for Scandinavians during the Viking Age. We’ve since learned that they were cleanliness-oriented, bathed weekly, and paid particular attention to their appearance. We know now that women decorated their clothes with colorful beads among other shiny objects, and the men groomed their beards daily. So with all of this new information available to us, the question stands: how did they wear their hair?

Contrary to popular conception, long hair was not universally a sign of a free warrior. In fact, long hair was well known to be a hazard during combat. Historians have noted that very short hair may have been reserved for slaves, but there exists evidence in the form of statues which contradicts this notion. Evidence from the archeological record—which includes statues, statuettes, and picture stones—shows men with many variations of hair cuts. Some may have worn their hair shoulder-length. Others may have had bowl-cuts. Many may have trimmed and groomed their beards into goatees. It appears that, precisely as it is today, hair styles may have been a form of self-expression.

By the end of the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia imposed rules surrounding vanity, ending the varieties of hairdos among Scandinavians (for a while). The Bayeux Tapestry shows us that military men during this period wore short hair, particularly in the back (pictured below).

Ultimately, the evidence points to a culture that allowed self-expression. This may be a hard pill for some to swallow, but it appears the eccentric hairstyles fashioned by the Vikings in the History Channel’s series of that name may be closer to reality than the idea that they all had long, free-flowing hair.

For a more in-depth analysis of how the Vikings wore their hair, I highly encourage you to read this article by The Viking Answer Lady on the subject.