C.J. Adrien's Blog, page 14

July 17, 2018

American Vikings: Did the Greenland Norse take Native American Wives?

It’s a well-known fact of history that the Vikings got around, both figuratively and literally. They reached distant lands, as far as Bagdad in the Middle East and Newfoundland in North America, and they tended to leave behind far more than their trade goods. Vikings, as we best understand them, were prolific progenitors all across the world. They took wives in distant lands, they sometimes brought those wives back to Scandinavia, but predominantly they left behind their genes where they roved. Considering all of this, one question about the American Vikings* remains an elusive mystery to us all: did they take Native American wives in North America?

To answer this question, it is essential to explore the evidence we have for Viking settlements in North America, as well as the sagas, which tell the story of the activities of the American Vikings. From the evidence, we may then deduce the plausibility of whether or not they took native brides.

*A quick note about nomenclature: throughout this article, I will be using the term “American Vikings” to describe the Greenland Norse who established colonies in the Americas. I have used the term interchangeably with “Greenlanders” and “Greenland Norse” in certain portions, particularly those where the Greenlanders were forced to abandon their colonization attempts. All of these terms refer to the same group of people who attempted to establish themselves on the American continent.

The American Vikings: Origins

The story of the American Vikings begins in Norway in the second half of the tenth century when a man named Thorvald found himself on the wrong side of the law. Little is known about what exactly he did to land himself in that position, but we do know it involved the killing of a few people. Thorvald fled into exile and moved to Iceland where he believed he would have a fresh start.

Eric the Red (Eiríkur rauði). Woodcut frontispiece from the 1688 Icelandic publication of Arngrímur Jónsson’s Gronlandia (Greenland). Fiske Icelandic Collection.

Thorvald found redemption in Iceland where he became a farmer and raised a family. After his death, his son Erik took charge of the farm. It did not take long for his likeness to his father to shine through. The Sagas of the Icelanders tell us this of Erik’s first run-in with the law:

Then did Eirik’s thralls cause a landslip on the estate of Valthjof, at Valthjofsstadr. Eyjolf the Foul, his kinsman, slew the thralls (slaves) beside Skeidsbrekkur (slopes of the race-course), above Vatzhorn. In return Eirik slew Eyjolf the Foul; he slew also Hrafn the Dueller, at Leikskalar (playbooths). Gerstein, and Odd of Jorfi, kinsman of Eyjolf, were found willing to follow up his death by a legal prosecution; and then was Eirik banished from Haukadalr.

Erik’s spat with his neighbor over a few slain slaves landed him in exile, just like his father. According to Icelandic law of the time, his property would be confiscated, and no one would be allowed to shelter him. Others could kill him without cause and with impunity. Interestingly, the court who decided his punishment for the murder of Eyjolf agreed against full outlawry; they instead sentenced him to a lesser sentence and ordered him to pay a fine and leave Iceland for at least three years. The lesser punishment allowed Erik to gather his property, family, and kinsman and move.

With no land and no option to return to Iceland or Norway, Erik had to find a new place for his family to live and thrive. He had heard through stories told in Iceland of a man named Gunnbjørn Ulfsson who, while sailing from Norway to Iceland, was blown off course. When Gunnbjørn finally arrived in Iceland, he reported having discovered a new land far in the north where none had ever before sailed. Left with few other options, Erik followed a rumor across the northern Atlantic and made landfall in what would one day be called Greenland.

Summer in the Greenland coast circa the year 1000 by Carl Rasmussen

According to Erik’s Saga, Erik spent three years exploring Greenland’s coastline. Having satisfied his sentence with Icelandic law, he returned to Iceland and reported what he had discovered. His saga reads:

“In the summer Eirik went to live in the land which he had discovered, and which he called Greenland, ‘Because,’ said he, ‘men will desire much the more to go there if the land has a good name.’”

Thus began three centuries of colonization of Greenland by Scandinavians. It is from this colony that the first voyages to, and colonization attempts of, America got their start. The story of the Greenland colony is a fascinating one, but what is essential to understand for this article is that Scandinavians had colonized Greenland and began to push evermore West.

The First European Settlements in America

Statue of Thorfinn Karlsefni is Philadelphia

A few years later, a man named Bjarni Herjolfson set sail for Greenland to visit his father. He drifted off course and found himself a long way off from where he had intended to sail. When he corrected his course and continued along his journey, he spotted new land to the west, which he reported to the Greenlanders when he arrived. His accidental discovery inspired attempts by the Greenlanders to find and to explore the western lands. The Saga of the Greenlanders relates to us five separate voyages of discovery, led by Erik’s son Leif.

Leif Erikson is perhaps the most famous Viking Age Scandinavian of them all. He is credited with discovering the American continent centuries before Columbus and has earned a place in popular culture in both North America and Europe. For all the attention he receives, the Saga of Erik the Red gives him little credit. In contrast to the Saga of the Greenlanders, where Leif plays a central role, the Saga of Erik the Red condenses the account of the discovery of America into a single voyage and credits a man named Thorfinn Karlsefni with leading the expedition and with the discovery of Vinland, even though the first Greenlander to set foot in the Americas was Leif.

When the Greenlanders set sail for North America, they searched for ideal locations to establish a new colony. They named the places they found on their way in ways that have allowed historians to figure out their modern equivalents, and to piece together the trajectory of their voyage. For example, they named one place Helluland, or Land of Stone Slabs, which historians have associated with Baffin Island. Next, they discovered a land with thick forests of spruce and larch, which they called Markland, and further on they sailed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they discovered a land they called Vinland.

Coast of the Remote Peninsula in Sam Ford Fjord, northeast Baffin Island

The Saga of the Greenlanders names only one settlement in America, Leifsbudir, or Leif’s camp. No one knows for sure where it was, but historians have placed the settlements of the American Vikings named by the Saga of Erik the Red. The first was Straumfjord, and it is the settlement mentioned in the sagas most likely to have been the one found in archeological digs in L’Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland. A second settlement, called Hóp, was used transiently to launch expeditions for timber to ship home to Greenland.

L’Anse aux Meadows has proven an exceptionally rich archeological site that has greatly informed our understanding of the American Vikings. We know from the evidence that they brought cattle and other livestock, built houses made of turf, and had ironworks. Interestingly, no barns or structures for livestock have been found, which has led some historians to theorize that the settlements in North America were never meant to be permanent colonization, but rather a logging operation to send timber home to Greenland where there were no trees.

The sagas spend little time describing life in the North American settlement, but quickly move to describe the interactions between the Greenlanders and the Native Americans who already lived in the area. They called the natives “Skrælling,” and at first relations between them were amicable. It did not last.

The American Vikings’ Relations With the Skrælling Turns Sour.

Vikings and Skraelings by Angus McBride. Photo credit: Osprey Publishing.

Relations with the Skrælling began on as positive a note as one might have hoped at the time. The Saga of Erik the Red tells of a vast host of Skrælling in canoes who appeared near the Norse settlement of Hóp one morning to investigate them. The Greenlanders set up a market and traded cloth for pelts and other goods. All was well until one of the bulls, who roamed the grasslands freely with the other cattle, charged at some of the Skrælling and sent them running.

“Now it came to pass that a bull, which belonged to Karlsefni’s people, rushed out of the wood and bellowed loudly at the same time. The Skrælingar, frightened, rushed away to their canoes, and rowed south along the coast. There was then nothing seen of them for three weeks together.”

When the Skrælling returned, they attacked the Greenlanders with strange and frightening weapons. Caught off guard by the attack, the Greenlanders retreated. Sole Karlsefni’s wife, Freydis, stood her ground. She called out to the men and said, “Why run you away from such worthless creatures, stout men that ye are, when, as seems to me likely, you might slaughter them like so many cattle? Let me but have a weapon, I think I could fight better than any of you.”

She faced the Skrælling, pounded her breast with her sword, and sent them running for their canoes.

Eventually, the Greenlanders realized that they would not endure long with constant attacks from the Skrælling, so they abandoned the settlement of Hóp to return with their livestock to the main settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows. It is here that the mention Greenlander-Skrælling interactions end in the Saga of Erik the Red, and the fate of the main settlement remains unknown.

Did the Vikings take Native American Wives?

The Saga of the Greenlanders mentions that the Vinland colony had a major demographic problem: most of those who moved there were men. With women in short supply, and considering the Vikings’ reputation for proactive procreation, it would not be a considerable stretch of the imagination to think that they may have satisfied their needs and desires with the locals. However, the evidence for Viking-Skrælling coupling is close to nil, and the accounts given in the sagas do not inspire confidence.

Let’s start first with the archeological evidence. At L’Anse aux Meadows, there is evidence of trade between the American Vikings and the Skrælling in the form of nuts that only exist many miles to the south. Perhaps the Greenlanders sailed further inland, but the more plausible explanation is that the natives traded the nuts for other goods. From an archeological perspective, there were Viking-Skrælling relations, the extent of which is unclear.

With little evidence archeologically, we must turn to the sagas for answers. Nowhere in the sagas is there any mention that a Greenlander took a Skrælling wife. We do, however, have some thin evidence on how the Greenlanders viewed the Skrællings. Recall the incident where the men fled a Skrælling attack, and the only one brave enough to face them was Freydis. She called the Skrælling “worthless creatures” which tells us that there may have been a measure of dehumanization propagated by the Greenlanders. More disturbing is the account in the Saga of Erik the Red where Greenlanders happened upon some sleeping Skrælling and just slaughtered them. If there is evidence for anything in the sagas, it’s that the Greenlanders were unequivocally hostile toward the Skrælling.

If there is no archeological evidence and no textual evidence in the primary sources, what was the point of going through the whole story of the American Vikings? A recent paper published by Agnar Helgason of deCODE Genetics and the University of Iceland turned up some surprising and controversial evidence that at least one Skrælling bride may have been brought back to Iceland. The proof is in the DNA of today’s Icelanders. The findings have sparked all manner of rumor and conspiracy theories, and have led to a lot of people asking the question: Did the Vikings take Native American Wives?

The study, which dates back to 2010, found 80 living Icelanders with a genetic marker that is only found in Native American populations. Agnar Helgason proposes that the variation began with a single woman who passed down the variant through the generations. Genetic testing is still in its infancy, and even Helgason admits that his findings are not concrete. In a 2010 National Geographic article, he explained, “It’s possible that the DNA variation came from mainland Europe, which had infrequent contact with Iceland in the centuries preceding 1700. But this would depend on a European, past or present, carrying the variation, which so far has never been found.”

There is no clear and straightforward answer to the question of whether the Vikings took Native American brides. To date, there is no evidence, genetic or otherwise, that any Greenlander DNA was passed along in Native American populations. What we can say is that from the archeological and textual evidence, there is no indication that this was the case. Especially in regards to the Sagas, it appears the Vikings had no interest in the natives except to slaughter them. Even if the recent genetic evidence proposed by Agnar Helgason proves correct — and it’s relatively shoddy evidence — it would only indicate that one Native American made it into the Icelandic gene pool, which would mean whatever the story, it was an isolated incident and does not constitute any trend.

Did the Vikings take Native American wives? For now, the answer is probably not. The answer could change, however, if new evidence emerges to prove otherwise. As always, check out my selected bibliography to find out more about the Vikings and their history.

The post American Vikings: Did the Greenland Norse take Native American Wives? appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

February 16, 2018

How Tall Were the Vikings?

There exists a peculiar perception among the general public that the Vikings stood taller than other Europeans of the Viking Age. Books, shows, and even some notable museum displays paint a portrait of tall and powerful men with keen skill at killing others. Luckily, the Vikings buried many of their dead in a way that preserved their bones and, through diligent osteoarcheology, we can say with some degree of confidence how tall Viking Age Scandinavians were. How tall were the Vikings? Read on to find out.

How to answer the question: How tall were the Vikings?

As with everything to do with the Viking Age, nothing is certain, nor is it likely written in stone (both figuratively and literally). The evidence for how tall or short the Vikings may have been can only be deduced from those pieces of evidence we can find. Written sources on the subject are unreliable for two reasons: first, they were written by the victims of Viking raids (clerics) who often embellished certain details; second, the most detailed of the written sources were composed long after the fact, and thus have little chance of being accurate. Thus, archaeology stands as the only sound method for determining the average height of a Viking Age Scandinavian.

Luckily for us, this questions has been explored by historians and archaeologists alike since the beginning of Viking studies. As with every issue I attempt to tackle in my blog, the answer is not straightforward. We must first take into account that the Viking Age is a broadly defined period that spans more than 300 years. Also important to note in such an investigation is the fact that geographic distinctions, variations in weather and harvest, as well as plagues, warfare, and any number of other factors can affect a population’s height in a particular location at a specific time.

With this in mind, the following is some of the research that has been done on the subject.

How tall were the Vikings in Iceland?

In 1958, Jon Steffanson composed an essay titled “Stature as a Criterion of the Nutritional Level of Viking Age Icelanders” in which he compiled known data about the heights of men and women found in Icelandic cemeteries that date to the Viking Age. Iceland is a fantastic place to do such research since the people who settled the island broadly qualify as Vikings. As luck would have it, my friends at medievalists.net have published the essay for all to read for free (click the title of the article above to read it).

To summarise his findings, Steffanson looked at the bones of 86 individuals who lived and died in Iceland in the 10th century (except for a select few skeletons that predate the others). He found that the average man of the time stood between 171 and 175 cm tall, and the average woman stood between 157 and 161 cm tall. Interestingly, when Steffanson compared these figures to 20th century Icelanders, he found that the average height of both men and women had remained relatively consistent. Icelanders only began to grow taller, on average, starting in the 1950’s, which is precisely what we tend to find in other European nations.

How tall were the Vikings in Sweden and Denmark?

Viking Age Scandinavians in Sweden and Denmark do not appear to have been any taller or shorter on average than their Icelandic counterparts. In his new book, The Age of the Vikings, Anders Winroth explores the subject of heights not to answer the question of how tall the Vikings were, but how their heights fluctuated as a criterion for how healthy and well fed these populations were (similar to what Jon Steffensen had done for Icelanders in 1958). In regards to the Fjälkinge grave site in Sweden, he writes of the Viking Age skeletons:

Concerning the averages, these heights are on par with those of the Icelanders of the same period. What’s more interesting is that the Fjälkinge contains graves of generations who were buried before and after the Viking Age. These graves show a slight dip in the average heights of men and women in the Viking Age. From this grave site (and this site alone), it appears that Scandinavians were shorter during the Viking Age than before and afterwards. What these findings mean I will leave to another blog for another day.

In Denmark, similar research has been done to find the average heights of men and women during the Viking Age. This research, as summarised by Mr Winroth, found the following: “The average height of Viking Age skeletons in Denmark is 171 for men and 158 centimetres for women.” (pg. 163)

How did the Vikings compare with other Europeans?

Conveniently, someone did the research to answer this question as well and summarised his findings in an easy-to-read-chart found at the end of his essay, Health and Nutrition in the Preindustrial Era: Insights from a Millennium of Average Heights in Northern Europe. Looking at data from archaeological findings, Richard Steckel of Ohio State University, an economist by training, found that Vikings Age Scandinavians were no taller than people in other places at that time, including the British Isles and Mainland Europe.

Things to keep in mind about the Vikings

Remember that Viking Age Scandinavia was a stratified society. Historian Neil Price recently proposed in an article for National Geographic that Viking Age Scandinavian society was set up more like the plantation system in the Southern U.S. states before the American Civil War than anything else.

“This was a slave economy,” Price explains. “Slavery has received hardly any attention in the past 30 years, but now we have opportunities using archaeological tools to change this.”

Due to the inequalities of Viking Age Scandinavian societies, the more prosperous and healthier members of the community would have grown taller than their servants and slaves. Also to note is the fact that the Vikings had to import slaves to meet the demands of their farming system, so there was a lot of intermixing of populations going on that could have affected heights.

Another point to note that may interest some of you is defining what the word Viking means, what the word describes, and how that might affect how we interpret the findings. If we use the word Viking to describe all Scandinavians of the Viking Age, then the sources and evidence discussed above make sense and satisfactorily answer our question. However, if we restrict our meaning of the word Viking to only those who left and roved foreign lands, we will find the above discussion lacking in every respect.

The Takeaway

We only have the evidence we have. Many factors can influence a population’s height, and considering the geographical dispersal of their population and the time span separating the first Vikings to the last, it’s hard to say definitively what their average height was. What we can say through archaeological evidence is that Vikings were not taller or shorter than their southern neighbours. We can also say that, similar to other European countries, the men and women of Viking Age Scandinavia were shorter than the people who live there today.

Learn more about the Vikings by reading some of these books:

[image error] [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]

The post How Tall Were the Vikings? appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

February 6, 2018

Drinking Horns: Were They Really Used by the Vikings?

Modern portrayals of the Vikings seem to be obsessed with horns, particularly in regards to those worn on the head (as part of the helmet) and those used for drinking alcohol. While the former has been proven false time and again – THE VIKINGS DID NOT WEAR HORNS – the second use, drinking from a horn, is a much different story. According to modern depictions, Vikings have a pseudo-monopoly on drinking horns, but the Vikings certainly were not the first to use them. Were Viking drinking horns really a thing? They were, but perhaps not exactly how you had envisioned.

What did the Vikings use to drink alcohol?

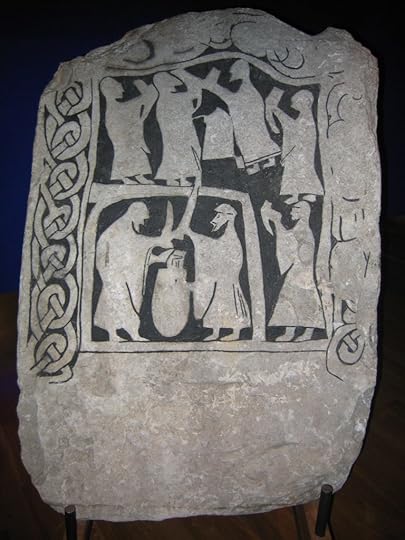

Drinking horns have been found scattered across the Viking Age archaeological record, from grave finds to pictorial evidence. No evidence is more compelling than the depiction of a drinking party, painted on a stone in Gotland in the 8th century, and which depicts every attendee of the party holding a drinking horn.

Does this mean all Vikings drank exclusively from drinking horns? No. We must remember that the artist was likely paid by a chieftain who was much concerned about his enduring reputation, and therefore he would have asked the artist to make it look like the best party there ever was.

The reality is that the Vikings would have used whatever was available to them to drink their ale. The most primitive vessels may have been small cones made of rolled birch or rowan bark. Bowls and goblets would have been the most commonly used vessels to drink, made from whatever material the owner of it could afford. Believe it or not, some Vikings could afford glass chalices, though these would have been extremely rare.

What place did drinking horns have in Viking society?

Drinking horns, historians believe, would have been a luxury item used almost exclusively for special occasions and rituals (such as ritual drinking). Horns were difficult to procure, mainly since animals were exceedingly expensive to raise in Viking Age Scandinavia. Hence, they held tremendous value, and only a wealthy chieftain or his family could have afforded one.

This does not mean less wealthy folk did not also enjoy the occasional drink from a horn. Viking culture demanded largesse from chieftains and kings. Leaders recruited and retained the loyalty of their warriors by showering them with gifts. A polished, decorated drinking horn would have made any warrior of the day extremely happy.

Were drinking horns invented by the Vikings?

No. Drinking horns were nothing new by the time the first Vikings set sail for Lindisfarne. In fact, drinking horns had had a long history dating back to antiquity. Julius Caesar, famed emperor of Rome, observed the use of drinking horns by the Gauls (who lived in modern-day France). He described their use in his book, De Bello Gallico:

“The Gaulish horns in size, shape, and kind are very different from those of our cattle. They are much sought-after, their rim fitted with silver, and they are used at great feasts as drinking vessels.”

Further Reading:

[image error] [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]  [image error]

[image error]

The post Drinking Horns: Were They Really Used by the Vikings? appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

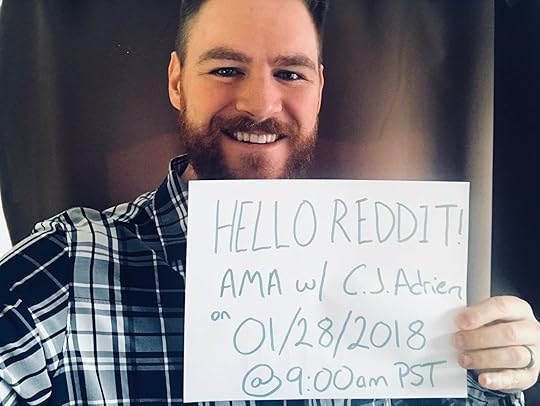

January 21, 2018

IAmA Proof for C.J. Adrien on 9/28/18

December 8, 2017

How historical is historical fiction? An Interview with Bestselling Author Eric Schumacher

In July of 2017, I attended a panel discussion on the authenticity of historical fiction at the International Medieval Congress at the University of Leeds. While several authors of note were present, conspicuously absent were a few who I thought would have meaningfully contributed to the discussion. Chief among them was Bernard Cornwell, whom I interviewed this past September. Today I have the honor of interviewing another author who I believe would have made an excellent addition to the panel: bestselling author Eric Schumacher, author of the book series Hakon’s Saga.

The topic of the round table was defined as follows: “Fiction offers a degree of creative freedom unavailable to the scholar, yet as both readers and critics, we desire authenticity in these texts – particularly because, for many, such texts are the first point of contact with the medieval world. Thus, historical fiction as a genre raises important questions. How ‘historical’ is it? How does the fiction writer balance creativity against the restraints of historical ‘accuracy’? What is the relationship between research and storytelling? This round table discussion will explore these issues, as well as practical aspects of writing and publication, with published fiction writers whose works can be broadly classed as ‘medieval historical fiction’.”

Eric Schumacher, thank you for taking the time to answer the panel questions.

How historical is historical fiction? What does the term historical fiction mean to you?

How historical is historical fiction? What does the term historical fiction mean to you?I would like to think that historical fiction is very historical. Meaning, it should transport the reader back to that bygone period in time. Readers should get a good sense of what it was to live in that time and in that setting, based on what we know. To me, historical fiction is the telling of a good story in that historical context.

What is the relationship between research and storytelling?

I think research is great for unearthing stories, for putting historical facts in order, and for understanding what it was like to live in the past; but it should never get in the way of a good story. As a writer, you want the characters to come alive on the page, you want the plot to carry you along, and you want the setting to lend to the authenticity of the story. Research can and should support all of these things, but in a way that doesn’t bog down the story with unnecessary detail.

What is historical ‘accuracy?’ Can authenticity exist in fiction writing?

My books take place in the Viking Age. We know much of events that occurred in that age and how the people lived, but new facts are coming to light all the time. Given that, it’s impossible to be 100% accurate, but with thorough research, we can certainly try our best. That accuracy lends itself to authenticity. However, there are certain judgement calls an author has to make for the sake of the story that can affect authenticity. The hope, for me, is to find a good balance between those two.

How do you balance accuracy, authenticity, and creativity?

That’s a great question. I start off by staying as close to the facts as we know them. That’s not always easy, especially for the Viking Age, when facts are in short supply. For instance, birth dates of certain people can vary in historical texts. Dates of certain events can vary. The location of battles can vary. So there’s much we don’t know, but there is still enough to provide plenty of historical guideposts. Once those are set, I then overlay a story, and try my best to put the two together in such a way as to tell the most entertaining, and most plausible, story possible.

Where authenticity plays a big role for me is not only in the setting, but in the mindset and motivations of the characters. It’s all too easy to overlay a modern way of thinking on an ancient character. So I frequently stop myself to ask whether I’m approaching a problem from a modern point of view or from a Viking point of view. Of course, we have no way of knowing if I’m 100% accurate in that thinking, but there’s enough research out there to at least point the way.

Sometimes, it’s a judgement call whether to exercise our creative license for the sake of the story or for the sake of authenticity. For instance, authenticity demands that I use the old Norse form for names of people, places, or things. I usually use the modern form. Why? Because I’d rather have the reader focus on the story than try to pronounce a place name like Þrœndalǫg for the sake of authenticity. Others will disagree, but that’s OK.

How do you access research materials? Does academia hold a monopoly on the information necessary for historical fiction writing?

Written research materials are everywhere (in libraries, online, etc), but those materials don’t hold a monopoly on the information necessary for historical fiction writing. Rather, I would say that they give me a skeleton for my writing. For instance, with research you can dig up interesting stories that might make a good novel. You can find fascinating factoids to use in your writing. You can gather dates of certain events that affect your plot either directly or tangentially. That said, relying solely on research for stories about Vikings isn’t always possible because scientists and archaeologists and historians are still putting the pieces of the Viking Age together! That’s partly why I love writing about this period in time — I get to dream up plausible relationships between what we know occurred, what might have occurred, what certain people might have been like, and so on. You get to put the meat on the bones of history, and I love that!

What is the responsibility of the historical fiction writer?

I would say there are two. The first, and most important, is to tell a good story. The second is to use history to help tell that story, but to do so responsibly. Overload your story with historical facts and you end up with an historical text book. Embellish or change facts too much and you end up with something closer to fantasy.

More about Eric Schumacher

Eric Schumacher is an American historical novelist who currently resides in Santa Barbara, California with his wife and two children. He was born and raised in Los Angeles and attended college at the University of San Diego.

At a very early age, Eric Schumacher discovered his love for writing and medieval European history, as well as authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Those discoveries continue to fuel his imagination and influence the stories he tells. His first novel, God’s Hammer, was published in 2005. God’s Hammer is currently the #1 bestseller in Norse and Icelandic fiction on Amazon.

Eric Schumacher’s Books:

The post How historical is historical fiction? An Interview with Bestselling Author Eric Schumacher appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

November 4, 2017

Why Are the Vikings So Popular?

For those who study the Vikings professionally, there is an intrinsic fascination that drives their desire to study the Viking Age in the same way that others are drawn to ancient times, the medieval period, or even contemporary history. Yet, the Vikings’ popularity also manifests itself in popular culture, and has captivated a wide audience for nearly two centuries. From Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, a 19th century opera based on Norse and Germanic mythology, to today’s Vikings on the History Channel, the Vikings have captivated the imaginations of people across the world. This brings up an intriguing question: Why are the Vikings so popular?

Disclaimer: This is not a particularly historical post, but rather my own musings on why the Vikings have become so popular in popular culture. Everyone, it seems, has some notion of who the Vikings were, whether true or a fabrication, and the appeal of the Vikings appears to be spreading beyond Western nations. Here I will examine why the Vikings first became popular (in a very condensed summary) and why they are more popular than ever today.

First, Let’s Talk About Scandinavia

Scandinavia is arguably the easiest place to define the Vikings’ popularity. They are the region of origin of the Vikings, and Viking history is their history. Fascination with the Vikings in Scandinavia is akin to a fascination with chivalry in France, with the Moors in Spain, or the Romans in Italy. It is part of their national history and narrative, and it is their ancestry (for the most part). Therefore, the popularity of the Vikings in Scandinavia is easy to see and to understand. When I broach the subject of the popularity of the Vikings, I do so for areas outside of Scandinavia, and the reasons I will postulate for their popularity will not necessarily apply to Scandinavian countries.

How the Vikings First Gained Popularity in Western Europe

Beginning in the mid 19th century, the governments of Europe, both nascent democracies and established autocracies, sought to bend the narrative of history to build or increase the authority of their governments. In France, for example, the fledging revolutionary government created an official national narrative in which modern France was the product of the Carolingian empire, a holy Christian institution that helped to stabilize Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. In England, the official historical narrative began with the Anglo-Saxon kings, like Alfred the Great, to emphasize that the English monarchy had a long and rich history, and to reinforce their legitimacy to the people they ruled. These narratives were used to incite national fervor and support for the government, a phenomenon we call nationalism today.

It is within the context of nascent nationalism that the study of the Vikings began. Not surprisingly, the Vikings were immediately painted as a heathen enemy who threatened Christian civilization and had to be defeated (us against them). In fact, the triumph of Christendom over “the ravages of heathen men”, as written in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, was regarded as a pivotal, divinely ordained achievement, exploited by the governments of Europe as a means to further incite national pride and reinforce their legitimacy to govern.

This early historical construct of the Viking Age has created a litany of inaccurate perceptions of the Vikings that persist to today. For the history buffs out there, I share your pain. But it is the fictional representations of the Vikings, first begun in the 19th century, and perpetuated until today, that has led to what they represent to popular culture. However inaccurate, their popularity is directly derived from the caricatures popular culture has created for them based on shaky historical interpretation (and fabrication).

What is a Viking in Popular Culture?

Let’s put the historical Vikings aside for a moment and define what a Viking is in popular culture. To do this fairly (albeit anecdotally), I asked my wife, who knows close to nothing about Viking history, to describe a Viking. Here’s what she said:

“They were brutes. Bearded, dirty, mean and violent. Strong and superstitious. Didn’t they believe in magic? Just…just bad. But kinda sexy, too? I don’t know.”

Believe it or not, she’s never watched the History Channel’s Vikings, but she essentially described Ragnar Lothbrok, the show’s protagonist. Love it or hate it, the show has created the perfect caricature of what a Viking is to popular culture, minus the horned helmets. And it is this caricature that has allowed the Vikings to conquer popular culture.

How the Vikings Conquered Popular Culture

There are many subjects that have captivated modern audiences: Vampires, Werewolves, Wizards and Witches, and Vikings. Wait…how do Vikings fit in with Vampires? To answer this question, let’s first deconstruct why Vampires have become popular in recent times.

They’re ancient: Vampires are allegedly ancient creatures that began to roam the earth in the distant past.

They’re mysterious: For all we think we know about Vampires, they are still incredibly mysterious. They only reveal themselves to a select few, and their origins are always cast in shadow.

They’re dangerous: Vampires are first and foremost killers. The danger they pose makes our imaginations run wild with fear, which excites us.

They’re immoral/do not share our sense of morality: Vampires are a great “other” who live outside the bounds of our society and do not adhere to our societally imposed moral constructs.

They’re a forbidden pleasure: You’re not supposed to like Vampires. They’re the bad guys. So being attracted to one in a sexual way is a forbidden pleasure. As we all know, forbidden pleasures are a huge turn-on for many people.

If we start to run through the list with the Vikings, we quickly start to realize that they fit the bill. Are they ancient? Yes. Are they mysterious? Of course! Are they dangerous? The most. Are they immoral? Duh…Ragnar! Are they a forbidden pleasure? Considering they have been painted as “the other” for nearly two centuries, I’d say so! And thanks to Harlequin Romances, I think we can say with relative certainty that there’s a certain sex appeal to them.

Now, I could delve into the psychological reasons why all of these traits are attractive to broad audiences, but I’m not a psychologist. All I know is that people are attracted to these sorts of things, and the Vikings, as defined in popular culture, possess the right “stuff” to have broad appeal.

Is the Popular Culture Portrayal of Vikings Bad?

There are many who would argue that the popular culture portrayal of the Vikings is a tremendous disservice to society. It’s reflective of how poorly most people understand or care to understand history, and a bane on the real study of the Vikings by academics. I argue the opposite.

In an age where history and the arts are increasingly lacking funding, the rise of Vikings in popular culture has actually been a benefit to Viking studies. Interest in the subject has led to tremendous advances in the field in the past two decades. Every week, it seems, there is a new discovery, or a newly established dig to expand our understanding of the Vikings’ past. Funding in academia is a fickle thing, yet it seems Viking studies are in less of a shortage of such funds than other subjects, particularly in Europe.

For me, it is more in the interest of us all to embrace the aspects of the Vikings that give them broad appeal, and to leverage their popularity to further the funding and research of the real Vikings, as well as other topics. Understanding the past is a tremendous benefit to our society, so if enduring watching people troll around with horned helmets on Halloween helps to expand our breadth of knowledge in some way, in my opinion, it’s worth it.

There is a limit to this benefit, however, particularly when fictitious caricatures of the Vikings are used to legitimize racist or intolerant groups. An unfortunate reality with the popular portrayal of Vikings is that it has been far too easy for white supremacist groups to bastardize the historical Vikings to suit their ideologies. This, of course, is a conversation for another post, but it is worth noting in regards to whether we should allow the popular culture portrayal of Vikings to endure unchallenged.

Why do you think the Vikings are so popular? I welcome your thoughts in the comments section below.

The post Why Are the Vikings So Popular? appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

September 13, 2017

How historical is historical fiction? An Interview with Bernard Cornwell

This past July, I attended and spoke at the International Medieval Congress at the University of Leeds. It was a tremendous honor for me to join fellow authors Justin Hill, James Aitcheson, and Kelly Evans on stage for a round table discussion on the topic of historical fiction and the role it plays in presenting the medieval world outside of academia. Yet as I sat among my peers at the session, I could not help but think that for such a prestigious event, with a room full of academics as our audience, one person remained conspicuously absent. That person was Bernard Cornwell.

Bernard Cornwell is arguably the most well known and widely read author of medieval historical fiction. With series spanning most of the medieval period and beyond, including his series Saxon Tales and Grail Quest, I felt that his insights on the topic we discussed would have been invaluable to us and to our audience. Although he had been invited to Leeds, he was unable to make it due to a previous engagement. However, I personally reached out to him to see if he might be interested in participating in our discussion post-conference to the benefit of my readers and, hopefully, some of the folks we had in the audience during the session. Bernard Cornwell graciously accepted my invitation to be interviewed on the topic.

The topic of the round table was defined as follows: “Fiction offers a degree of creative freedom unavailable to the scholar, yet as both readers and critics, we desire authenticity in these texts – particularly because, for many, such texts are the first point of contact with the medieval world. Thus, historical fiction as a genre raises important questions. How ‘historical’ is it? How does the fiction writer balance creativity against the restraints of historical ‘accuracy’? What is the relationship between research and storytelling? This round table discussion will explore these issues, as well as practical aspects of writing and publication, with published fiction writers whose works can be broadly classed as ‘medieval historical fiction’.”

A very special thanks to Bernard Cornwell for taking the time to answer my questions.

How historical is historical fiction? What does the term historical fiction mean to you?

It’s really a circular answer! If the novel isn’t historical then it isn’t historical fiction! What it means to me is that any historical novel tries to offer the reader a picture of another era, and tries to make that picture as accurate as possible. Writers create worlds, and the world of an historical novelist is the past! I’m sure we don’t get it right much of the time, but still the background to the story should evoke a long-gone era to the reader…what it looked like, smelt like, was like! So the background world has to be as accurate as possible, regardless of what is happening in the story.

What is the relationship between research and storytelling?

The first rule of writing the book is to leave out all the irrelevant research (about 90%).

I can’t say there’s a huge relationship, though very often the research will suggest a story idea? You certainly can’t write an historical novel without doing vast amounts of research, but the first rule of writing the book is to leave out all the irrelevant research (about 90%).

What is historical ‘accuracy?’ Can authenticity exist in fiction writing?

You tell me! No one will probably ever know what it was truly like to live in a long-gone past, so we all make educated guesses and we hope we get it right! Plainly the more research a novelist does then the greater the chance that his guesses are accurate, and the more detail he amasses of the period then the greater the authenticity! And yes, authenticity certainly exists in fiction, it’s the authentic detail that creates the fictional world. Is it fully authentic? I doubt it, but we try!

How do you balance accuracy, authenticity, and creativity?

By remembering that I’m not an historian. I’m not here to teach Anglo-Saxon history or any other history. I’m a story-teller, so my first responsibility is to tell a story! That story is fiction, even if it’s based on a well-known episode of history. So accuracy and authenticity must take second place to the story. There’s obviously a limit to that; a fiction writer can’t get away with letting the French win the battle of Waterloo…if he or she does than it ceases to be an historical novel and becomes a fantasy novel. But we do all make changes. In Sharpe’s Company I have Richard Sharpe fighting his way through the breaches of Badajoz, and that never happened. But the drama of that night was in the dreadful breaches, not in the second assault (which worked), and if the book was to convey the full horror then Sharpe had to be where the fighting was at its worst. So I changed history to make a better story, but then confessed what I had done in the book’s historical note.

How do you access research materials? Does academia hold a monopoly on the information necessary for historical fiction writing?

I read books! I visit the places! I buy books! I read more! No, academia doesn’t hold a monopoly, but plainly it’s a great place to start! I’m hugely grateful to all the wonderful academics who do the original research which I use, but there are vast areas of life which are not covered by academia…the small details of life. Some of the best material comes from the weirdest places and some come entirely from the imagination!

What is the responsibility of the historical fiction writer?

To entertain! To give the reader a compelling story. Not to be dull. And to create a background which is as convincing as possible and, so far as it is possible, true to what we know about the past!

Thank you Bernard Cornwell for your answers!

Acknowledgements

None of this would have been possible without the hard work of the session organizers, Melissa Venables and Katrina Wilkins of Nottingham University, to whom I offer my sincerest gratitude and thanks. Thank you also to the other participants, Justin Hill, James Aitcheson, and Kelly Evans.

Photos from the Conference IMC 2017

The post How historical is historical fiction? An Interview with Bernard Cornwell appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

June 30, 2017

The Viking Raid at Lindisfarne: Who Attacked the Monastery?

It was an event that shook the Christian world to its core. So traumatic was its destruction that historians have agreed it should mark the official beginning of the Viking Age, even though it was not the first violence the British Isles experienced at the hands of the Vikings. The anglo-saxon chronicle records ‘terrible portents’ to the events at Lindisfarne in 793 A.D. Located on Holy Island in the far north of England, it is written that the monastery saw powerful storms on the eve of the Vikings’ arrival.

Who attacked Lindisfarne?

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle notes,

“793. Here terrible portents came about over the land of Northumbria, and miserably frightened the people: these were immense flashes of lightning,and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. A great famine immediately followed these signs; and a little after that in the same year on 8 January the raiding of heathen men miserably devastated God’s church in Lindisfarne island by looting and slaughter.”

The speed at which the Vikings are said to have arrived caught the monks completely by surprise. Reconstructions in past years have estimated that on a clear day a ship might only be seen as far as 18 nautical miles, a little over an hour’s journey for a longship with the wind at its back. If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is to be believed, the Vikings neither arrived on a clear day nor did the monks appear to have had an hour to flee.

Wrote the monk Alcuin, a leading theologian of his day, of the event:

“We and our fathers have now lived in this fair land for nearly three hundred and fifty years, and never before has such an atrocity been seen in Britain as we have now suffered at the hands of a pagan people. Such a voyage was not thought possible. The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans – a place more sacred than any in Britain.”

Alcuin’s description certainly lends to the idea that the clergy at Lindisfarne did little to flee their attackers. It may have been that the Vikings arrived so suddenly that they had no time to prepare at all. Yet for all the descriptions we have of the destruction caused at Lindisfarne, we have little in the way of a description of the men who carried out the raid, other than ‘heathen’ or ‘pagan’. Who were the men who raided the island? Where did they come from?

Were the Vikings at Lindisfarne from Norway?

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lists an entry from the year 787 A.D., six years before Lindisfarne, in which ‘Danes’ arrived at the port of Portland. It describes a brief encounter in which the port authority was killed for attempting to levy a tax on the heathens. The chronicler Aethelweard further expounded on the events of that day, and mentions the men introduced themselves as being from the Hordaland region of Norway.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reads:

“A.D. 787. This year King Bertric took Edburga the daughter of Offa to wife. And in his days came first three ships of the Northmen from the land of robbers. The reve then rode thereto, and would drive them to the king’s town; for he knew not what they were; and there was he slain. These were the first ships of the Danish men that sought the land of the English nation.”

Aethelweard’s account tells us that Vikings from the Norway region had, at this time, the ability to sail from Norway to Southern England. It certainly contradicts Alcuin’s assertion of, “Such a voyage was not thought possible.” The account is also evidence that the Vikings of Norway were interested in and traveling to the British Isles, and so it is not a long leap to say that it is likely that the attackers at Lindisfarne may have been from Norway, not Denmark. Unfortunately, we cannot know for sure. The raiders at Lindisfarne did not introduce themselves as they had done in Portland.

Were the Vikings at Lindisfarne from Denmark?

There is one brief chapter in history that may lend itself to helping us understand who the first raiders were and, roughly, why they attacked. In 792 A.D. the Emperor Charlemagne moved to suppress a Saxon rebellion under the leadership of a man named Widukind. His action was decisive and bloody. During the battle on the banks of the Elbe River, the Franks captured 3,000 Saxon prisoners. As a means to send a message to the rest of the region, Charlemagne ordered the prisoners be baptized in the river. There, the priests recited their benedictions as the Frankish soldiers held their victims underwater until they drowned.

The event, known as the “The Massacre of Verdun” was perfectly in line with Charlemagne’s tactics to subdue pagan tribes. However, Widukind, the leader of the Saxons, was brother in law to the king of the Danes, Sigfred. News of the massacre undoubtedly reached the Danish court, and word of Charlemagne’s acts of violence would have spread across Scandinavia. It was yet another brutal, violent display of power by the Carolingians, the latest in a long series spanning decades.

From what historians can tell from the sources, Danish raids along the coast of Frisia intensified almost immediately, leading to an infamous raid on Dorestad, to which Charlemagne supposedly bore witness, if we are to believe the account given by the chronicler Einhart in his work, Two Lives of Charlemagne. The very next year, the attack on Lindisfarne occurred, and what happened there has led some to believe that there was a direct connection between the two events. A source about the attack by the twelve century English chronicler, Simeon of Durham, who drew from a lost Northumbrian annals, described the events at Lindisfarne thusly:

“And they came to the church at Lindisfarne, laid everything to waste with grievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted steps, dug up the altars and seized all the treasure of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers, took some away with them in fetters, many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults, some they drowned in the sea…“

Some historians have taken this last passage to mean that the Vikings purposefully took priests to the water to drown them in order to make the point that they were retaliating against the encroachment of Christendom on Denmark. Other historians have disputed this as mere coincidence. If true, it might mean that the men who attacked Lindisfarne were from Denmark, not Norway. They would have begun their raids in Frisia, and then made the leap across the channel and up the coast.

So, Who Attacked Lindisfarne???

Although there is some light evidence to suggest it was either Danes or Norwegians who attacked Lindisfarne, it is impossible to know for sure. It just as easily could have been a church conspiracy – an inside job – to incriminate the ‘heathens’ for a barbaric act to spur greater efforts to convert Scandinavia. One could say that Alcuin’s inconsistency, such as his assertion that, “Such a voyage was not thought possible,” despite knowing that Norwegians had already visited Portland, point to a cover-up and overt effort to demonize the men from the ‘North’. Perhaps Alcuin, who was in exile in Charlemagne’s court at the time, was the architect of a political hit job, and Lindisfarne was actually sacked by Frankish raiders under his orders – all so he could convince Charlemagne of the need to invade Jutland.

Of course the ‘inside job’ narrative is ridiculous, but it’s useful insofar as it showcases the nature of the study of the Vikings. We don’t actually know all that much about the Vikings and many of the major events that marked that time period, and even well-documented and ubiquitous events are based on extremely light evidence and few primary sources. Therefore, in answer to the question of who attacked Lindisfarne, all we can really say is it was probably Norwegians, maybe Danes, but ultimately we do not, and cannot, know for sure.

Subscribe to my Newsletter

* indicates required

Email Address *

The post The Viking Raid at Lindisfarne: Who Attacked the Monastery? appeared first on C.J. Adrien.

March 28, 2017

Do You Use the Word Viking Correctly?

A contentious issue that has long plagued both the study of Vikings and the place of Vikings in popular culture is the proper, accepted usage of the word Viking itself. Language matters, and how a person uses language greatly affects their worldview and how they perceive people, objects, and concepts. It is no surprise, then, that there are a growing number of people who are dismayed by today’s liberal use of the word Viking to describe a great number of things that it originally did not. Here I will attempt to clarify the origins of the word Viking, its usage across the ages, and the evolution of its modern usage, specifically in non-Scandinavian languages.

The Origins of the Word Viking

The word Viking is derived from Old Norse. While its origins are not well understood, and historians are divided over where precisely the word originated, we do know the word began not as a noun, but as a verb. The Saga of Egill Skallagrimsson offers us one of the most compelling examples of the word’s original use, and his is the closest example to the actual usage of the word in its native language. In his opening passage, he describes a man named Ulfr as a man who, “lá hann í víkingu og herjaði,” which translates (roughly) to, “he was roving and fought.” In this context, the word Viking described an activity, roving, rather than the man.

Later in his saga, Egill goes on to use the word differently in the following passage:

‘With bloody brand on-striding

Me bird of bane hath followed:

My hurtling spear hath sounded

In the swift Vikings’ charge.

Raged wrathfully our battle,

Ran fire o’er foemen’s rooftrees;

Sound sleepeth many a warrior

Slain in the city gate.’

Here Egill uses the word to describe a group of people partaking in a certain action, which tells us the word Viking was also used to describe the men who partook in “roving and fighting”. It is this dual usage that has led historians to say that the word Viking described a profession. Jugglers juggle. Traders trade. Vikings go viking.

The Decline of the the Word Viking

As the Viking Age came to a close, so too did the profession of roving and fighting. Hence, usage of the word Viking declined. Old Norse spent the next several centuries morphing into the modern languages of Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, and Icelandic. Although Icelandic is the closest modern language to Old Norse, Old Norse itself is considered a dead language, like Latin. In this context, the original usage of Vikings disappeared almost entirely for many centuries until it experienced a revival led by 19th Century historians from Western Europe.

Revival of the Word Viking

Spurred by the prevalent Romantic movement of the early 19th Century (1800-1850), a new interest in the medieval period took hold in Western Europe. Part of this movement saw a growing interest in a little-known, poorly understood part of early medieval history, the Viking Age. Historians flocked to the field with keen interest, seeking to shed light on this “dark” age. At the time, there was not yet the concept of the “Viking Age” but it is during this time that the concept was developed. It is also the 19th Century historians who first delineated the Viking Age between 793 A.D., the attack on Lindisfarne, and 1066 A.D, the Norman invasion of England. Through their efforts they discovered an enigmatic people who plagued the early kingdoms of Britain and France, and whose origins they traced to Scandinavia.

We must remember that during the romantic period, there had not yet been any ship burial discoveries, no archeological digs of any significance, and the primary sources about the Viking Age were spread across Europe, many of them hidden away in age old university archives or privately owned by Europe’s gentry. Misconceptions abound in this early period, and it is within this context that the word Viking made its appearance in non-Scandinavian languages.

A new political force also began to take hold in Western Europe, a concept that would be responsible for the deaths of 100 million people in the following century: nationalism. Beginning in the mid 19th century, the governments of Europe, both nascent democracies and established autocracies, sought to bend the narrative of history to suit their political aims. In France, for example, the official national narrative was that modern France was the product of the Carolingian empire, a holy Christian institution that helped to stabilize Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. In England, the official historical narrative began with the Anglo-Saxon kings, like Alfred the Great, to emphasize that the English monarchy had a long and rich history, and to reinforce their legitimacy to the people they ruled.

It is within the context of nascent national fervor that the study of the Vikings began. Not surprisingly, they (the Vikings) were immediately painted as an enemy who threatened civilization and had to be defeated (us against them). In fact, the triumph of Christendom over “the ravages of heathen men”, as written in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, was regarded as a pivotal, divinely ordained achievement, exploited by the governments of Europe as a means to further incite national pride. This fearsome enemy from long ago, however, did not yet have a name. What then to call these invaders who attempted to thwart the Christian kingdoms of Europe?

No one really knows where 19th century historians, and later, society, picked up the word for use in non-Scandinavian languages. It may have been borrowed directly from the Scandinavians of the day, or perhaps taken directly from the Sagas of the Icelanders. Historian Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough explains in her book, Beyond the Northlands, that the first modern use of the word Viking was recorded in 1807, three years before Queen Victoria’s coronation. The word wasn’t reserved for the “men who roved”, but instead referred to the entire Norse world. It is, woefully, a product of the “us against them” mentality, and an unfortunate oversimplification and mischaracterization of a time and people we now know to have been far more complex than previously acknowledged. From 1807 forward, this usage dominated the histories and the arts of the 19th and 20th centuries, and is by-and-large how most people use the word today.

So, Do You Use the Word Viking Correctly?

It all boils down to effective communication. Who is the audience? What is their level of knowledge in regards to the Viking Age? In his most recent book, The Age of the Vikings, Historian Anders Winroth takes the time to define his own usage of the word Viking to make his use of it clear to his audience:

His is a great example, and anyone who uses the word should be careful to define how they intend to use it, and to make clear the differences between its various usages. I, for example, use the word Viking more interchangeably because my intended audience are those just beginning to explore their interest in the Viking Age and who may not yet understand how its modern usage differs from the past (hopefully this article helps to clear that up!). However, in writing more in-depth histories, I focus my usage of the word on the “men who roved”.

March 16, 2017

How did the Vikings Treat the Elderly?

One would not be remiss for thinking that the elderly were few and far between during the Viking Age. Historical estimates for the average life expectancy in Dark Ages Europe are extremely low, something around 30 years, and so the issue of the elderly and how they were treated at the time has somewhat been ignored. Recent scholarship, however, has discounted the concept of average life expectancy because it was heavily skewed by child mortality rates. We’ve since learned that once an individual made it to adulthood, they stood a fair chance of making it to their golden years. So how did the Vikings treat the elderly? How did older individuals fit into their society?

Within the Context of Viking Society

The standard unit of society in the Viking Age was the Grand Family, meaning they lived together in shared longhouses, often with multiple generations and multiple family units. One household consisted of multiple couples of husbands and wives, their children, and if alive, their parents. Hence the famous longhouses, which were capable of housing a large number of people, estimated at anywhere from 10 to 20 members of the family. This much we know about the Vikings: the elderly would have lived in-home, and would have been cared for by their immediate family. This we know from the Icelandic Sagas.

We must be cautious, however, when dealing with any one particular source on Viking society. The Icelandic sagas are useful insofar as studying Icelandic society at the end of the Viking Age, but not necessarily applicable in regards to other Scandinavians at the time. Viking Age Scandinavia was a fragmented society, and individual communities had different practices, even different deities (the Pagan Norse were Polytheistic), and so knowing how Iceland did things is far and away from understanding how the rest of Scandinavia did them.

Within the Context of Archeology

Details on how exactly the elderly were treated are difficult to come by for the simple fact that the Vikings left no written record of their daily lives. Thus, historians have had to turn to archeology to find answers. Burial mounds and buried ships across Scandinavia, and even abroad, have proven to be an invaluable boon to our understanding of the Viking Age. In them, archeologists have found tools, weapons, clothing, bones, animal remains (all referred to as grave goods) that have greatly improved our understanding of their societal structure, technology, and to some extent, their culture.

Osteoarcheology, or the study of bones, has helped paint a picture of funerary practices, as well as identify the gender and age of individuals contained in burial mounds. This has helped, in part, to demonstrate that many of the people buried did reach older age. Some remains have been found to have belonged to individuals who exceeded sixty years of age. The Oseberg Ship Burial, for example, contained the bodies of two women, one of them estimated to have been between 60 and 70 years of age, and badly afflicted with arthritis. So we know that there were people who made it to an age that we would today consider elderly, but how exactly they were treated remains somewhat of a mystery.

So, how did the Vikings treat their elderly?

It’s impossible to say for sure, but what we do know is that there were elderly members of society, and if the Icelandic sagas are any indiction, they would have lived as part of a larger family unit and been cared for by members of their immediate family. In-home care, it seems, was the only option at the time.