The Paris Review's Blog, page 56

May 11, 2023

Americans Abroad

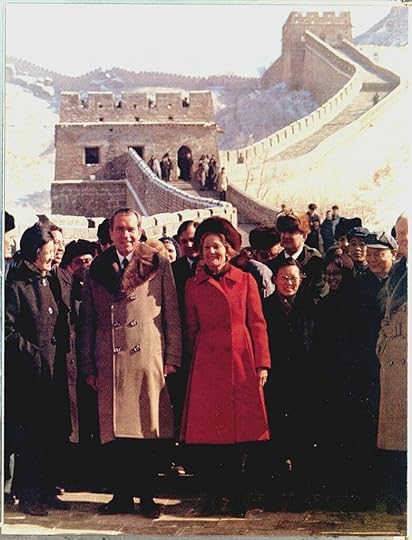

Richard and Pat Nixon in China, 1972. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

By the time I saw Nixon in China during its 2011 run at the Metropolitan Opera, it had become a classic, if not an entirely undisputed one. It had made it to the Met, at least, with its composer, John Adams, conducting, and James Maddalena, who originated the role of Nixon in the 1987 premiere at the Houston Grand Opera, back at it, now nearly the age Nixon was when he made the trip. A friend of mine, with theatrical élan, bought out a box for a group of us and encouraged formal dress, as if we were in a nineteenth-century novel. He showed up in a tux. I don’t remember my outfit, but I’d be surprised, knowing myself, if I managed anything more presentable than a mildly rumpled off-the-rack suit. At the time, I was working as an assistant to a magazine editor who regularly attended the opera, in full formal dress, with a pair of its major donors, fitting in an elaborate meal on the Grand Tier during intermission. My handling of his invitations gave me a surprising proprietary sense about the place. I didn’t feel that I belonged, of course, but at least I had a narrow help’s-eye-view of its workings. In the upper deck, and even in our box, my friends and I had the sense of superiority that comes from being broke and artistic among the rich and, presumably, untalented.

Not that I had any major insight into the opera at the time, this one specifically or the art form more generally. I’d sat in the cheap seats on a few occasions, trying to rouse myself awake for the end of Tristan und Isolde, once, with a Wagner-loving girlfriend. I’d even stood in the back row of the orchestra for Leoš Janáček’s From the House of the Dead, feeling obligated as a Dostoyevsky loyalist to bear witness. (All I remember is a general brownness and a grim, monochromatic score. It was, after all, a Czech opera about a Russian prison camp.) I did, however, have an abiding interest, bordering on mania, in the pathos of conservative politics, and only a person who has lost interest in the world could fail to be interested in Richard Nixon. The friend who had arranged this outing was, among other things, a news junkie and former Republican, and his relationship to the former president was characterized, like the opera’s relationship to its subject, by a complicated mix of irony and enthusiasm. Dramatic renderings of Nixon tend toward the sweaty and profane (as in Robert Altman’s Secret Honor) or the broadly comic (Philip Roth’s novel Our Gang, or the 1999 film Dick, starring a young Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams, an overlooked gem surely due for reappraisal). But Adams’s monumental, hypnotically Glassian score and Alice Goodman’s dense postmodern libretto invest Nixon with a weird if inarticulate dignity that he rarely displayed in life. The striving and paranoia are tamped down, replaced with yearning naïveté and statesmanship.

Though the opera remains true to the publicly known contours of the actual trip, Nixon in China’s Dick and Pat are as much stand-ins for Americans Abroad—hopeful, a bit bumbling, but fundamentally decent, albeit with the power of the world’s wealthiest country at their back—as they are representations of real people. (Nixon, it’s worth noting, was still alive when the opera premiered, and was invited to the opening. A few years later his representative said that he didn’t attend because he “has never liked to see himself on television or other media, and has no interest in opera.” Okay!) In his arias, Nixon delivers a garbled mix of clichés, non sequiturs, impressionistic memories, and Ashberyian koans, the most famous of which, “News has a kind of mystery,” is repeated in dizzying variations soon after Nixon descends from his Boeing 707 and shakes hands with Chou En-lai (as the Chinese premiere’s name is unorthodoxly rendered in the libretto). The song lodges in one’s brain immediately—I’ve been continually exclaiming “News! News! News!” at my four-month-old son—and serves as a kind of motto or benediction for the entire work, simultaneously insistent and ambiguous. It’s the exclamation of a man who is marveling at the mythmaking apparatus that he has been an active beneficiary of and that will ultimately destroy him. It’s the vagueness that makes it transcendent, a half-formed thought one might jot down in a notebook and turn over in one’s head for days. A kind of mystery?

There’s an emptiness at the core of Nixon in China that is appropriate, given that it’s about political pageantry, the kind of nonevents that Joan Didion identified as the stock-in-trade of modern politics in her 1988 essay “Insider Baseball.” One of opera’s chief methods is to turn private emotions into grand spectacle, to give voice to feelings that could never be as beautifully expressed as they are in a duet between two doomed lovers. Nixon in China turns superficial spectacle into another spectacle, a copy of a copy. There is action—Nixon meets with Mao; Nixon and Chou deliver toasts at a banquet; Pat goes on an official sightseeing tour—but there is little dramatic movement. Even when we do get insight into the “private” Nixon, Pat, Mao, et al., in quieter scenes that take place behind closed doors, what is revealed is not fundamentally different from what is presented publicly. Adams’s score ebbs and flows, churning on and on, threatening, but never tipping over into, catharsis. The work steadily resists resolution—it ends with an extended coda, taking up the entire third act, in which the characters prepare for bed.

At the time, in 2011, I remember enjoying the spectacle, and puzzling over what it all meant. News … news … news … I had been to the opera so infrequently that I assumed any gulf between my understanding and the work’s intention lay with me. But the passage of time hasn’t brought a grand interpretive theory, and anyway, that isn’t really what this art form requires. Over the subsequent decade and change, I’ve found in opera a refuge of old-fashioned virtuosity, a place where, give or take the occasional malfunctioning Ring Cycle set, one can reliably admire vocal athleticism and swaggeringly baroque production values, regardless of one’s level of prior knowledge. Of course, understanding the source material, the nuances of the score’s texture and performance choices, the historical context of the work’s composition, and much else, adds to the experience on an intellectual level—that is, in retrospect. But so much of the joy lies in the immediacy of the moment, which one can feel even as a know-nothing in the cheap seats, and supplement as desired in the aftermath.

On reflection, the very tentativeness that Goodman’s libretto invokes—a kind of mystery—suggests her and Adams’s philosophy. It’s not anti–great man theory, exactly, as it’s still very much an opera about history’s main characters. But the tenuousness of their position is made clear. They are tourists at the grand events they have set in motion, and their role is as much to comment and reflect on them as it is to shape them. They inhabit a world in which gesture has more power than reality. It was, in retrospect, the perfect opera to dress up for, and for pretending to be more than we were.

Andrew Martin is the author of the novel Early Work and the story collection Cool for America.

Making of a Poem: Michael Bazzett on “Autobiography of a Poet”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Michael Bazzett’s “Autobiography of a Poet” appears in our Spring issue, no. 243.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

It was a phrase. I was sitting in my backyard, with a legal pad and a few books, including Fady Joudah’s Footnotes in the Order of Disappearance and After Ikkyu by Jim Harrison, which contains the line “I was born a baby, / what are these hundred suits of clothes I’m wearing?” I was thinking about dislocation and baby-logic, and object permanence, and the idea of first encountering something through a sense other than sight. Hearing a bird before you see it, for instance. Or how a visual stimulus like a leaf-shadow fluttering in the wind moves on the wall above a crib. In my baby-mind, I imagine that light-flicker as something animate, moving of its own accord. When does a baby stop engaging with stimuli as pure image or pure sound and begin to imagine what caused it? I’ve often wondered what it would be like to be able to reexperience the dreams we dream in utero, or in the first months of life before language, before we consciously encounter words and narrative structure. How would they be ordered? Where would the images come from? Do we bring anything with us from the other side? Are there things already written into us?

For some reason, I’d written down some notes on language on my legal pad: “Language as energy, as predating culture, as something to discover …” And “Language as energy” leaped out at me, and I wrote, “I thought birds were pure sound / until I was 5 months old / and one fluttered to my sill / and into my sight.”

I say I was “thinking about” the above things, but really they were thinking inside me. Or simmering. Or humming. I don’t know what the verb is, but it’s not thinking.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write?

I came across the lines when I was typing up another poem from the pad, and I typed it up and played with the lineation and liked “I thought birds were pure / sound” as an initial first two lines, with the slant rhyme of bird/pure, the little head-fake that “pure” modifies “bird” (due to the enjambment) before it settles on “sound.” I liked the way it was moving, and tried to follow its sound, which led to “flutter” becoming “flicker,” echoed by “quick,” and “light” rhyming with “right.” It sounded kind of jaunty, so I just followed the voice.

The cigarettes arrived as a joke, but a joke that somehow included the final image, which surprised me and also felt pleasing and symmetrical, with the half rhyme of “curled” and “bird” echoing the opening stanza.

The whole thing came out pretty quickly, which happens sometimes. Not often.

The ensuing revisions were mostly just little tweaks. The biggest change was that “Having a smoke” became “Smoking a dart.” I heard it and I thought, Yeah! Get a few more consonants in there. The original title was “Ars Poetica,” but I changed it pretty quickly, because it didn’t seem the world needed another poem called “Ars Poetica.”

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

Besides the Jim Harrison, I had also written down an idea from Paul Ricoeur earlier in the notebook: “Information is the shadow of meaning.” I think that idea was lurking there, too. Poems tend to come in “families” for me, so it’s good to look at the whole legal pad. I was also doodling a bit, which I do when I’m writing in longhand.

What were you listening to or watching while you were writing this?

This might sound funny, but I was rewatching the entirety of The Sopranos during that whole period. A six- or seven-month project of rewatching. I think that’s probably where the “Fuck yeah” came from; it functions almost as a form of punctuation to my ear, the profanity not landed on, but drawn in on the inhalation. It’s not a register I work in very often. I almost hear it in Tony’s cadences, accompanied by that hopeful, puckish little-boy smile. James Gandolfini was so marvelous in that role. I’d pay a thousand dollars to hear him read this, as a little monologue: “… from my muddah’s purse!”

There’s also a little Mel Brooks in there, from Free to Be … You and Me, when he voices a baby in the opening skit with Marlo Thomas. I always loved the gag of a baby with a voice of a grown man, and now, in a way, that’s what I’ve become.

Michael Bazzett is the author of six books of poetry, most recently The Echo Chamber.

May 10, 2023

Musical Hallucinations

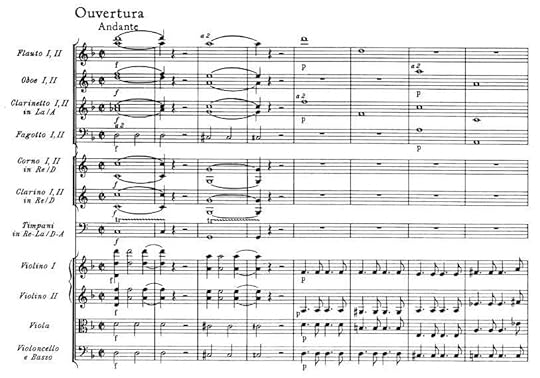

Sheet music of Don Giovanni. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CCO 3.0.

Don Giovanni keeps playing in my head, as if of its own accord. I wonder if I could be having musical hallucinations. I read an article about a woman who had musical hallucinations. She heard someone playing a piano outside the front door of her house. She went outside to look but nothing was there. The music played on, always vaguely nearby. Pretty soon the music was playing constantly—long passages from Rachmaninoff and Mozart.

She went to a doctor. Was she complaining? I wondered. I was already praying: Please let me have that disease where you hear a piano playing Mozart nonstop.

Time went on and she heard a marching band in the next room. A full church choir sang constantly in her kitchen. The doctors wondered: What would happen if she went to a concert? Would the concert drown out the music she was hallucinating, or would it all clash together in a musical storm?

It turned out that Bach fugues were able to drown out the music in her head. (Not surprising, since Bach fugues are the epitome of stern and strict, and would have the force to drown out everything else with their resolve.) But then the marching bands and the Rachmaninoff would start up again the minute the Bach fugues ended.

So if she listened to Bach fugues all day, then would she be normal? Or sort of normal?

The scientists attached electrodes to her head and tested her brain waves and looked forward to poring over the results, studying magnetic fields in her prefrontal cortex, etc. While the test was being administered, the woman was hallucinating a Gilbert and Sullivan opera. The scientists kept inserting the Bach to see if it canceled out the Gilbert and Sullivan

Meanwhile I’m thinking I wish I had Gilbert and Sullivan operas and marching bands playing in my head. Musical hallucinations—I’m praying for them. I’d have to pick the program, though. Oriental foxtrots. Argentine tangos. Guatemalan rumbas. Scratchy old recordings of 1920s French jazz waltzes.

But it might be more like the time I went to Scotland and kept hearing bagpipes in the distance long after I had returned home. That was pretty good, though. I wouldn’t mind hearing bagpipes in the distance all the time.

I asked my father (age ninety-seven) who he thought was the greatest Don Giovanni of all time. Ezio Pinza, he said promptly. I found a recording of this production, and its beauty is so thrilling that it makes even Erwin Schrott look slightly pale.

In case you’re wondering who Erwin Schrott is, he is the opera singer who played the role in Washington twenty years ago when I first moved to our nation’s capital. He was then a mere boy but a sublime Don Giovanni who wrenched my heart. Twenty years after that I saw him play the same role in a highly successful rotation as a middle-aged man but still the same enthralling heartthrob.

My obsession with him was momentarily shattered when I heard the Ezio Pinza version. I’m scared to listen to it as much as I want—all the time—in case I get sick of it. Could I ever get sick of it? Anything seems possible.

Music is an antidote for anhedonia. Sometimes you can’t feel. Let’s say you can’t cry. The beauty of music is that it can remove these restraints, defeat the lions at the gate. But it’s not always a sure thing. Anhedonia is a powerful enemy.

So the Ezio Pinza does put my dear Erwin Schrott a tad bit in the shade. There’s this 1940s American radio announcer summarizing the plot between the acts, however, which is annoying. Though he does have the quaint, archaic voice as in old movies from that era where you keep thinking: Did people really talk like that?

But the announcer’s stock interpretations of the action do not take into account the subtleties of the libretto. How all the women who decry Don Giovanni’s villainy and call for his demise secretly adore him and were secretly brokenhearted that he only wanted one-night stands from them. Elvira sometimes begs him to come back, amid the denunciations, etc.

Knowing Mozart as we do—his genius; his angelic quality, which would not be so angelic were it not mixed with some cynicism, immaturity, slapstick, darkness, prurience; and his being kind of a mess in some respects—he would never have conceived the opera according to the stock interpretation of prudish one-note morality.

A bunch of prudes wrote in to protest the deletion of the epilogue (the ensemble aria after Don Giovanni’s descent to hell where they’re all proclaiming the justice of his punishment) in the newer Erwin Schrott production. They protested not because they missed ten more minutes of towering rapture (the experience of Mozart’s music), but because they missed the moralizing. Like I said, a bunch of prudes.

Actually I do think Erwin Schrott stacks up to Ezio Pinza after all. But the point is really this: I watched an interview on YouTube with Erwin Schrott preparing for the Royal Opera House production in London—the production I watch over and over incessantly—and in this interview he says that everything good that has ever happened in his life has to do with music, and that it started twenty years ago when he first played Don Giovanni.

So I thought this must mean he had the same rotation I did, referring to the same moment twenty years ago when I saw him play the role that meant so much to him. And to me.

I’m hoping to attend a performance of Don Giovanni at the historic opera house in Palermo next fall—another rotation destined to produce a mad conglomeration of ecstasy. The rotation decrees that Don Giovanni will be the same, and it is I who am meant to be different. But I am not really that different. And I secretly rejoice to find the same girl with the same soul and personality now as when I first became obsessed with that opera (age twenty-two, New Orleans, streetcar rumbling past).

There is a theory that the world is divided into two kinds of people: continuers and dividers. The continuers can tell they are the same person they always used to be; the dividers continually change. Music is one proof in my case. The gift bequeathed by my father.

It started with Bach. Bach was the thing. With Bach it’s about the sternness. Take the Bach inventions. Glen Gould is too emotional about them. That detracts from their effect. Emotion in Bach must be earned—hard-earned, the result of bracing discipline. The atmosphere is firm, uncompromising, steadfast. Upright. Not upright as in morally upright, necessarily, just straight—a straight shooter, a straight arrow. An inexorable, unbroken bass line always braces the foundation, which highlights the sternness. The unwavering sternness.

This does convey an emotion, and that emotion is JOY. Joy is a more stern form of happiness.

I come from the town where jazz was born, a town whose personality is the exact opposite of the sternness of Bach, and my taste resides at those two opposite extremes. My friends there were wild. Ditto my first love. His thing was drinking and decadence (yet happiness and hope). My thing was Albinoni on a stern-green German lake.

One of my debauched friends used to play Bach fugues. It was a most incongruous spectacle: debauched friend with a talent for Bach fugues, which require the strictest discipline. But that was the thrill: residing in the incongruity.

There’s a movie about British explorers in the Amazon in 1910 hacking their way through the overgrowth in the depths of the jungle who suddenly come upon the incongruous spectacle of an opera being conducted on this remote and stifling stage. The orchestra is wearing white tie and tails, in the heart of the wilderness at this hidden opera. A degenerate baron in a beat-up white summer suit who runs the rubber plantation is the host (Franco Nero) and makes some mysterious comments.

An unknown pathos and sharp ecstasy lie in the incongruity, the intrinsic and extrinsic elements juxtaposed. Or on the boat in Egypt amid the green palms, the blue Nile, the waning afternoons, Schubert played on deck. At night Strauss waltzes played. The same wrenching pathos and sudden bliss as to the opera in the jungle.

***

For some years it was obvious that my father was getting frail. We were listening to opera in his study one day and reading the newspapers.

“Do you think an artist has to be crazy?” I asked him.

“Couldn’t hurt,” he said crisply, puffing on his cigar.

A marching band came out of nowhere down State Street. I ran outside to look and saw it turn down Garfield heading for the Park. Mardi Gras rehearsals—drumbeats in the distance, impending gaiety—like the parades that came down Dominican Street in the Black Pearl when I was little, with little Black girls in white dresses followed by a marching or jazz band. That’s where the talent was in that town.

I would walk to the church on the corner with Franciola, who would be singing the latest soul songs. I was wearing a pair of Mardi Gras beads that I exulted in, and as we approached the avenue, the world was wide with hope. But a shimmering realm of promise would lead beyond it one day to the outer world.

Now the shocking thing is how lackluster the outer world sometimes seems, when I leave my house in Washington, D.C., and how much more exciting and fascinating it is inside my head than out in the real world. The actual world. Not because of what it’s like inside my house. Because of how everything is arranged inside my head. Maybe the trick is to keep it all going with Bach-like resolve—what’s inside your head when you’re in the real world.

Opera is a cultivated taste. Like oysters, Scotch, and the New York Times Book Review—at least in my first youth in New Orleans those things seemed abhorrent, uninteresting, or extreme. But once you do cultivate an interest in those things, you’re bound to them for life with an almost religious fervor.

Still I must always fight my enemy, anhedonia. The antidote to anhedonia can be random. There is, for instance, an unprepossessing interlude, comparatively speaking, before the masked ball in Don Giovanni. Don Giovanni enjoins Masetto and Zerlina to be strong (whatever that means—maybe for him, according to his character, it means to revel unabashed in opportunities for lust and love) and put aside their sorrows. A seemingly innocuous interlude, yet the harmonies of their voices in the score at that seemingly innocuous juncture tear my heart and raise a tear by their stalwart beauty.

A stalwart joy, and yet I weep. That’s the mystery.

The mystery is that the emotion is not conveyed by words. One part conveys the stalwart joy, another piece funereal bereavement. Take Mozart’s Mass in C Minor, which seems to show an upward progression of pure sorrow, humanity trudging up a mountain to—to what? Possibly to Dante’s Paradise, except it’s kind of sad? In contrast to the soaring aspiration expressed by Mozart’s early symphonies.

My father took my younger daughter, Grace, and me to Venice when she was twelve. I had an epiphany in the courtyard of an ancient music conservatory laden with the grime of centuries while someone played the Italian Concerto by Bach on a glorious old piano. I burst into tears, and thanked God for reminding me of who I am and prayed to be that person again. As I had been lost.

When you’re young you spend a certain amount of time finding yourself; but in the middle of this journey of our life, you tend to lose your way. Probably the same amount of time it took to find yourself when you were young, is the amount of time it takes to recognize that you have lost your way again and must renew the search.

There I was transfixed by beauty, sobbing. A stalwart joy, and yet I weep. There I met that same odd girl I once was and reunited with her, transported by the music of the spheres.

Nancy Lemann is the author of Lives of the Saints, The Ritz of the Bayou, and Sportsman’s Paradise. “Diary of Remorse” was published in the Fall 2022 issue of the Review.

May 9, 2023

Dear Mother

The Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, ca. 1880. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In the second half of the seventies, when I was in my twenties, I wrote letters home to Ireland from Barcelona. Early in 1976, for example, from my pension on the corner of Carrer de la Portaferrissa and Carrer del Pi, I described my first visit to the Liceu opera house.

Dear Mother,

The walls in this small, cheap hotel are thin. The man in the next room listens to opera on the radio. He looks like someone who has seen little daylight, but instead he has seen many operas, as he tried to explain to me in broken versions of several languages. Two days ago, he was waiting for me in the corridor. At first, I thought a fire had broken out or the police had, once more, attacked the people. He was saying something that clearly would require quick action on my part. Having calmed him down and got a dictionary, I realized that he had seen a production at the Liceu that was special, and he believed that I, as a matter of urgency, should see it too. It was Puccini’s La Boheme, and it starred Montserrat Caballé.

It was hard to know what to do when I went to the box office. Some of the prices for individual tickets would also buy you a studio apartment in the city. I bought the second cheapest type of ticket. When I showed it to my opera-crazed neighbor, he peered at it for some time, turned it around to check the back, and then shook his head. But this made no sense. It was the precise opera he had recommended, in the very venue he had suggested. What could be wrong with this ticket?

On the night in question, I arrived in good time. When I showed my ticket at the front door, I was directed to another door, less grand and auspicious, at the side. From there began a set of stairs that rose endlessly and grew narrower as they got higher. When, eventually, I found my seat, I discovered that I had no view at all of the stage, none. Standing up would not help, because there was not enough head room to stand up. Soon, others arrived and took up the seats around me. All of us were men, most of us were alone, and all of us were sad.

We grew sadder when the music began, in the sure knowledge that the stage must be bathed in beautiful light and the costumes must be gorgeous and the set superbly crafted. When our descendants, if we should be so lucky, were ever to ask us how we felt when Caballé first appeared on the stage and when she said that she was called Mimi, we would have to say that we did not see her and that hearing her was no compensation, it merely made us bitter, a bitterness that entered our spirits that night and never left.

The problem arose in act 4. I could not bear it any longer as Mimi sang her farewell. I had paid my money, I needed to see what was happening on the stage so that I could write home about it. I could hear the singing and the orchestra as clearly as a hungry person can smell food. I felt a ratlike determination to see Caballé just once. Just once. I realized that leaning out from where I was would not work. I waited until a soaring moment, Caballé’s voice at its most splendid, and I not only leaned out but rested my two hands on the shoulders of each of the two men in front of me and propelled myself forward like a duck. That allowed me to catch a glimpse of the stage, just one glimpse, just for one second.

The men whose shoulders had thus been used went crazy. One of them called me a name that I will not repeat, especially in a letter to my mother, as it impugned my mother’s reputation in a way that is unmistakable. But, by that time, I had retreated into my cage, the place from where I could hear but not see. The problem was that my leaning had been less gentle than I had planned. I had clearly ruined the experience of a great high note for two members of the audience who had paid more money than I had.

And now they knew where I was.

When the opera ended, I did not wait for the applause. There is, as I have mentioned before, a fearsome set of policemen in Barcelona known as els grisos. They often glower at me suspiciously on the Ramblas. It isn’t merely that they have guns and batons but they have hatred in their eyes for people who do not know their place. I do not know my place. I needed to get out of that building before anyone reported me to nearby members of els grisos.

Back in the pension, my neighbor had a long face. He pointed at his ears to signal that I must have heard the music, and then he covered his eyes to mark the fact that I was among the unfortunate who did not catch sight of the almighty Caballé. I made signals like someone removing a blindfold. I let him know that I had in fact seen her, I had caught a glimpse of the great soprano in one of her most exquisite arias. But I did not explain how.

That, Mother, is all the news for now. The weather is nice. The dictator is still dead. Els grisos are still on the street.

Your loving son.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is The Magician. Belinda McKeon interviewed him for issue no. 242 of The Paris Review.

May 8, 2023

Mozart in Motion

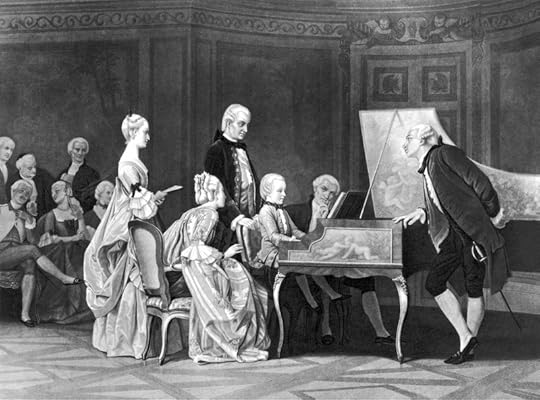

Young Mozart performing for Louis François de Bourbon in Paris in 1766. Gustave Boulanger, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Opening nights of new operas may be the most fraught of all. So many things have to go right. The paint must have dried on the backdrops, the soprano’s throat must be clear of infections and the tenor of overly distracting fits of pique. The orchestral players must be confident that their strings or reeds will behave themselves. Enough copies of the score must have gone out, and everyone needs to know which big aria has been cut at the last minute. Large amounts of money hinge on the airy stuff that musical performance comprises. An eerie tension awaits anyone without enough to do—but everyone generally has far too much to do. No one can control how the audience will react, though sometimes in the eighteenth-century sections would be paid to get their reactions right. Mozart’s era often left it unclear who was meant to be in charge of this broadly purposeful chaos; the role of the conductor had, for one thing, not yet attained its later clarity. As the first notes got closer, an entire social world was readying itself to be funneled into drama and music.

In the autumn of 1787 an impresario called Pasquale Bondini may or may not have felt in control of such a night. He ran the resident opera company at the recently built Nostitz theater in Prague whose success earlier in the year with a staging of Le nozze di Figaro quickly led him and his codirector to commission a new Mozart opera. It seems to have been Mozart who gravitated toward the figure of Don Juan and the old Spanish folk tales about his lascivious career that had already inspired literary and operatic versions across the century. Prague had adored Mozart’s rampantly expansive, vertiginously original opera about the rebellious valet Figaro, so it must have struck him as a good place to hit with an even more drastic reinterpretation of his world’s cultural possibilities. The composer was a local hero in Prague at a point when he and Vienna were unsure how enthusiastic they remained about each other. Writing the opera for a place other than the imperial capital might have seemed a retreat had he not used it to leap into yet more artistic freedom, and his popularity in Bohemia must have charged the mood and raised the stakes for this first night. In Don Giovanni, his fusions of elegance with fieriness speak with almost painful directness of an artistic desire both to summarize his culture and to move it onward.

Mozart would have been vibrantly hard to pin down on this first night, a small and indistinct man caught up in a blur of needs and actions, hardly visible once he had taken charge of the music and his dark creation was beginning to unfurl. The opera wheels through eighteenth-century conventions and reference points, but the score could not be more distinctly his, treating them with a copious freedom that renders them luminous. His daily levels of nervous energy must have helped keep him free of any great anxiety on even the biggest musical nights. But lashing excitement among the audience and the orchestra does seem to have marked the launch of Don Giovanni, after hitches and delays that cannot have lessened the feeling that something major was coming. The fierce blazonry with which the overture opens declares the opera’s high stakes. Nervous tension is on the agenda for anyone listening. Something new was in motion within the opera, but its innovations are cloaked and refracted by atavism and a sumptuous feel for conventions. Its early audiences were exhilarated and bewildered.

Mozart’s new opera finally premiered very late in October; the richly dressed listeners would have met with murky, bumpy streets around the opera house as seven o’clock approached. The imperial governor’s own money had built the theater a handful of years earlier, a space ready for novelty in a city chafing against decades of indifference or even neglect from its Habsburg rulers in Vienna. A restless underlying resentment and a skittering cultural inventiveness pervaded the Bohemian capital, making it the perfect landing place for such an exuberantly complex opera. Erratic, smoky light would have drifted around an auditorium only barely separated from backstage chaos as the opera’s action opened. In Mozart’s century an audience did not stop being noisy and sociable just because the performance was under way; it may often have given them something else to talk about. Maybe Mozart felt some burst of control once the thing had started, as he willed the music onward and coaxed his performers on. But the opera was also now ceasing to be his. At the heights of art, power and its loss can join hands.

The opera’s shadowy overture throws it into events in which sex, violence, comedy, and loss briskly overlap. Giovanni’s flight from one of his exploits brings him face to face with Donna Elvira, an abandoned lover who has been on his trail. He abandons her again now and leaves his manservant and sidekick, Leporello, to deal with her. We may feel momentarily disappointed that Giovanni has left the stage; the opera depends on his charisma and our appalled fascination with him. But the aria that Leporello comes up with is the point at which the opera becomes as fully itself as Giovanni is irreparably himself—it fuses charm with power and drastic moral truthfulness. It is known as the catalogue aria because it inflicts on Elvira an expansive, brutally playful enumeration of the lovers or victims that Giovanni has left behind. An ambiguous courtly swagger fizzes through Mozart’s music as it streams through arch and aching shifts of pace and texture; its artfulness is both dizzying and dizzy as mischief and cruelty embroil it. Comedy and bleakness mix in Leporello’s voice, and the nearly sobbing tenderness that seems close whenever he mentions Spain is punctured by the aria’s punchline, as he gives the appallingly precise number of 1,003 for his boss’s successes in that famously devout country. Elvira needs to hear who this man is, and even those in the audience familiar with the story need to hear his rapacity rampantly set out. But the awful truth is delivered here in a vein of brisk, outrageous comedy by a waggishly officious manservant. Whose side are these frisky violins on?

The opening of a new opera brought the disparate, spinning social and cultural forces of late eighteenth-century Europe together like no other occasion, and in this aria Mozart satisfies, while turning them inside out, all the motives of pleasure and excitement that took people to the opera. Europe was wavering on the brink of modernity, and Mozart became the key artist of the modern world because his music was richly fired by so many of the factors and energies at work in this process. Sometimes this Europe was as elegant as its nicest fictions claimed and sometimes it was as violent as its turbulent dreams suggested; the revolution in France whetted the culture’s vastest hopes, but using the guillotine became official policy there just a few months after the composer’s death. Mozart was the sharpest analyst of this era, and his music lets us listen in on the heartbeat and the brainwaves of modern experience in the throes of its emergence. He guides us through his restless historical time, and thinking more deeply about the world in which he worked should also change how we hear his music; our ears should open to more of what those beautiful sounds chase after.

The impact of Leporello’s aria comes partly from the acute, rueful parallels hidden within it—between the seducer’s voracity and the hunger for experiences, styles, and vistas that powers Mozart’s music. Giovanni’s manservant runs through a list of countries that have hosted his employer’s conquests, and gives us a prancing tour of the social classes and physical types indiscriminately pulled in. Mozart’s music is likewise expansively cosmopolitan and dashingly inclusive of influences and registers and possible listeners; sometimes it is all but desperately eager to please. Eighteenth-century music had readied itself for him by making itself the place where the culture could advance its possibilities with the utmost sophistication and ambition, at the same time as wildly enjoying itself. Music moved across boundaries and carried vistas of freedom more profusely even than the ideas of the French philosophes or the English novel’s cult of passionate sentiment. Mozart drew deeply on the craze for Italian styles of vocal music that had poured across Europe as the era’s most ardent cultural movement. Rapturous fandom and often rancorous controversy greeted such music across the culture, as it was carried far beyond Italy, and taken on or revised by musicians and singers from any number of centers. It enchanted popular audiences and the most backward courts and the most ambitious intellectual circles; the prominence of women singers and of castratos made it a sphere in which singular versions of individuality could make their dazzling voices heard. The liquid hedonism of this music, its technical bravura and its sophistication of outlook, had taken it to the heart of cultural life in staunchly monarchical Lisbon and heatedly bourgeois Amsterdam, and up into the unlikely cultural revolution imposed by Catherine the Great in Russia.

The most ambitious surges of musical form were electrically joined to the biggest social and political questions. At the same time, Mozart’s need to sell himself, the headiness with which he worked and his position as both a composer and a performer, make his music sharply porous to how he lived or what he thought or suffered. Mozart’s music swivels between any number of needs and reference points and agendas, keeping new compositional ideas or influences spinning alongside professional exigencies, ethical or personal dilemmas or interests, and larger historical forces and trends. His endless capacity for polish and finesse allowed him an endless imaginative multifariousness, and the result is that his music comes to us bearing dazzling questions. How does one thrive in a world full of change? How can people pursue new flavors of liberty while remaining generous and faithful? Can we combine high aristocratic tastes with commitments to democratic openness? We can find in an aria an account of how to move from a lament to possibilities of personal change; in a chamber work, ways of reconciling intellectual density with pleasure and panache; and in an orchestral piece, recognition of our need for both pluralism and coherence. At the core of Mozart’s work is the attempt to reckon with the coming of the modern, and the point of modernity is that it will be full of questions, about itself and everything that it contains or touches. A modern world breaks from its past and wants to know where that will leave it, or take it. New visions of culture based on innovation and change were taking shape all around him. In fact, Mozart was shaping them more deeply and playfully than anyone, because music was both the highest promise of happiness that his world gave to itself and the finest disguise that its more radical inclinations ever found.

Mozart was suspended between a deep but skeptical attachment to Europe’s patchwork of courts and hierarchies, and his deep intimations of the versions of freedom and selfhood and power that were on their way. Sometimes these intimations were euphoric and sometimes they were troubled. Mozart was deeply conventional yet driven to extremes of originality. He was highly ambitious but profligate with money and with his creative brilliance; he was a joker who was also capable of deep solemnity and severe moral earnestness. If we want to know how to live amid historical suspense, or how to be simultaneously serious and lighthearted in response to the dilemmas of our lives, Mozart’s music wants to show us. He could seem bewilderingly irresponsible personally, but his music became intricately answerable to opaque historical pressures, and to the pathos of human aspiration and disrepair. Mozart’s world was up for grabs, debating everything from optics to grain trade regulations and the moral status of luxury. Rococo pleasure gardens and masked balls pulled toward one vision of modernity while reformist zeal and the beginnings of modern political science pulled toward another—and revolutionary conspiracies and the massive expansion of state power toward yet others. Unflinching excitement about the new suffuses Mozart’s music, but it also longs for inclusiveness and coherence. Mozart was in on modernity at the point of its emergence, and he tells us not just about the universe that he worked within but about how we have kept wavering since, and how we live now. One question is how much we now really want a world that could again be up for grabs.

The success with which the composer’s music expressed its world has had paradoxical, disabling effects on how we listen to it. Mozart remains so culturally central that it can be hard to hear how volatile, strange, willful, or precarious his work can be. Its sheer number of attitudes toward modernity’s swerving approach is one reason for the inexhaustibility of his music—but the trickier or darker aspects of his vision can end up being elided. His music loves the marketplace, relishing its vibrancy and its willingness to give pleasure. The deep humanitarian pathos with which his work is riven involves not just moral protest against inequality and injustice, however, but surges of rebellious political desire. His music meditates on a world in which diverse visions janglingly coexist, but it also loves clearing the air for serene vistas of its own. It brims with the suggestion that another sort of modernity was once possible, one less vehement and crushing, one more plural and flexible. We often claim to despise the modern world that we have ended up in. Living without our contempt can itself seem hard to imagine.

Listening to music is a strange act, and Mozart’s music is an education fit for a world in motion and the selves in motion within it. The first night of Don Giovanni summarized his talent for swallowing his world whole. In one of many stories about his life as the opera emerged and flourished in Prague, Mozart’s wife keeps him awake through the night before it opens, so that he can finish composing the overture. In another he jumps out and grapples with one of the glamorous singers in the middle of a rehearsal, in order to get her to scream with terror as her character should. In the background wanders Giacomo Casanova himself, toward the end of his career as an important intellectual and an epochal libertine, who at the time frequented similar circles in the city to the composer. He may well have attended this first performance, and he may have discussed with Mozart the dark story that the opera reconstrues, and its resonances for a society unsure of its moorings. Stories like these are clues of how much this opera mattered, and how much it took on. Mozart pours the culture’s energies and wishes into a vision of the modern soul as endlessly on the run, ravaged by his own urges and powers. Giovanni’s manservant tells Giovanni’s abandoned lover truths that she both needs to know and hates, and the music moves through riffs and cascades and bleakly sweet dips of momentum which assert a tough and dazzling argument about how complex pleasure is becoming. The catalogue aria is a painstakingly offhand endgame for eighteenth-century music and all its elaborately charged versions of fun and charm and passion. But this means firing up its own new and acute versions.

We cannot decide whether our own late modern world is too fluid or too stifling, too changeable or too relentless or too inert. Incessant change itself ends up feeling stifling, and it is not clear even whether this is a tragedy or a comedy or a farce. Mozart loved mixing the tragic with the comic, cogency with levity, and despair with grace, and he knew that some of the most powerful responses to a creative work are fueled by how much contradiction or multiplicity it contains. The vim and the comedy of the catalogue aria are as exhilarating as its picture of a continent with its values upended by one man’s extravagant libido. But exhilaration is mixed here with cruelty, as the aria wheels through territories and categories with a spirit of violent flexibility drawn from Giovanni. Its expansiveness starts to feel grotesque, and so do the combinations of coolness and glee with which this odd manservant runs through the shadowy, crushing facts. The suaveness of the music leaves us nowhere to stand. Finally, the flighty, brutal mockery astir in the aria feels close to reaching out of the opera and turning on us. Are we inside or outside the world shown to us? We do not know whether to be fascinated or repulsed. The music is in motion and so is the opera’s moral world; we listen in inexorable motion too.

Patrick Mackie is a poet whose work has appeared in The White Review, New Statesman, and The Paris Review. A former visiting fellow at Harvard, he is the author of Excerpts from the Memoirs of a Fool.

From Mozart in Motion: His Work and his World in Pieces , out from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in June.

May 5, 2023

Movie Math

Sauvagette, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I love movie math. I love microrationalizing macroabsurdities, laser-focusing on hyperspecific justifications. 13 Going on 30 is a perfect proof. Once upon a time, it’s Jennifer Garner’s (Jenna’s) thirteenth birthday. She wishes she were thirty, she claims to her mom, having read a Poise magazine article touting the thirties as the prime of one’s life. “You’ll be thirty soon enough,” says her mother—and indeed, if Mom had known the film’s title, she might have clocked just how prescient she was. Jenna’s invited the popular clique, the Six Chicks, over for her birthday, despite the truth bomb from the boy next door, Matty, that “there can’t be a seventh sixth chick. It’s mathematically impossible.” The Chicks trick Jenna into “seven minutes in heaven,” that is, waiting blindfolded in a closet for a kiss (that never comes). When she realizes she’s been duped, she desperately chants the mantra she learned from Poise: “Thirty, flirty, and thriving.” By law of rhyme and the rule of threes, exactly thirteen minutes in, counting the opening credits, Jenna falls out of bed in her sprawling Fifth Avenue apartment.

At thirteen, Jenna’s too early for everything: a retainer around her top teeth, tissue paper stuffed down her shirt to make breasts. At thirty, she’s already running late. Jenna tumbles into a waiting car; ten minutes later, she’s in a meeting for the editorial job she didn’t know she had thirty seconds earlier. The boss, with chin hair plucked into a devil goatee, pins up fourteen nearly identical magazine covers: Poise and its rival Sparkle are side by side. June’s Poise features Jennifer Lopez’s ten secrets; Sparkle’s got her eleventh.

Math goes on. Manhattan-Matty and Jenna reunite, only for Jenna to discover that she’s been shitty to Matty in the seventeen-year blackout interim. There’s impossible real estate math: they live blocks away from each other, he in the Village with a sunken living room and a backyard, she near Union Square with a walk-in shoe closet. Even for 2004, the salaries don’t add up to a down payment on a fourth of one of them.

Time, like movie math, is bouncy: business day, lunar month, fiscal year. (I recently got into an argument about the existence of a “business week.” I argued pro: fourteen business days equals two business weeks.) I first watched 13 Going on 30 on a plane, flying backward in time. Now, I’m thirty-four going on seventeen. For the past five years, I’ve been teaching at the university where I did my undergraduate degree, but this is my last month there for the foreseeable future. It’s spring, so campus is getting ready for reunions. It’s a reunion off-cycle year for me—year thirteen—but Princeton’s reunions are famously a cosmic wormhole; even those of us who don’t believe in anything go into a New Jersey fugue state for a weekend that’s actually three days but one night. But in movie math, this all totally tracks: micro-obsessing over minutes lets you leap out of the frog-march of linear progression.

—Adrienne Raphel

First Reformed, Paul Schrader’s portrait of a small-town pastor suffering a crisis of faith, is also a story about equations, summations, and calculations of all kinds. I saw Schrader present the film recently at Metrograph, where I also started Archway Editions’s recent print publication of the screenplay, plus a reissue of The Transcendental Style in Film, Schrader’s seminal 1972 work of film criticism. The two books, taken together, are a kind of blueprint or formula for the movie itself—or maybe more like print transubstantiations of it. First Reformed, appropriately, is a movie structured around the Book. But it is also about math: “I will keep this diary for one year, twelve months, and at the end of that time it will be destroyed,” Reverend Toller says in the voice-over that opens the film. The plot proceeds by a string of numbers. 250: years that the eponymous Dutch church has been in operation; 2050: the year that we will no longer recognize the Earth as our own; 2,500: grams of Semtex wired to an ecoterrorist’s suicide vest (“Hamas-style,” according to the screenplay); $85,000: the charitable contribution made by BALQ Industries, a paper manufacturer, to First Reformed’s semiquincentennial Reconsecration celebrations; 22,978,929: the quantity of greenhouse gas emissions that make BALQ a Top 100 Polluter.

Schrader’s claustrophobic, calendrical pacing heightens the sense that our 113 minutes of runtime are a kind of countdown to the capital-E End. His characters suffer from a similar fate: Michael, one of Toller’s flock, is thirty; his wife, Mary, is in her second trimester. By his calculations, at age thirty-five, their daughter will be alive in a world that is “unlivable.” How, Michael asks his pastor, can one sanction such a pregnancy? Toller’s own son is already dead; following a “patriotic family tradition,” after Bush’s war on terror, and at his father’s urging, he’d enlisted in Iraq. “There was no moral justification for this conflict,” a repentant Toller says of that war. “Michael, whatever despair you feel at bringing a child into the world cannot equal the despair of taking one out of it.” Toller himself, alcoholic and periodically puking blood between diary entries, spends the movie avoiding the doctor’s appointment that might put an end date on his own life.

The movie is a study in a series of symmetries. Everything important arrives as symbolically doubled, first within the world of the film, then again, invisibly, in the much older story that haunts both Toller’s consciousness and Schrader’s script: if characters are often foils for each other, they are also incarnations of Biblical ones. If the pink Pepto-Bismol that Toller pours into his whiskey recalls an oil spill, it is also the blood of Christ. The brilliance of First Reformed is in the speed and grace with which these equivalences are formulated and then, just as quickly, dissolved. A (Christian) life, the film concludes, is not mathematical. Life cannot be counted, proven, or justified. People like to say that Jesus died when he was thirty-three; actually, according to historians, we don’t know for sure—he could have been thirty. Or thirty-six. And the Bible doesn’t give a number at all.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

May 4, 2023

A Letter from Henry Miller

Around the time he published some of his mostly famous works—Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, and Tropic of Capricorn, to name a few—Henry Miller handwrote and illustrated six known “long intimate book letters” to his friends, including Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Durrell, and Emil Schnellock. Three of these were published during his lifetime; two posthumously; and one, dedicated to a David Forrester Edgar (1907–1979), was unaccounted for, both unpublished and privately held—until recently, when it came into the possession of the New York Public Library.

On March 17, 1937, Miller opened a printer’s dummy—a blank mock-up of a book used by printers to test how the final product will look and feel—and penned the first twenty-three pages of a text written expressly to and for a young American expatriate who had “haphazardly led him to explore entirely new avenues of thought,” including “the secrets of the Bhagavad Gita, the occult writings of Mme Blavatsky, the spirit of Zen, and the doctrines of Rudolf Steiner.” He called it The Book of Conversations with David Edgar. Over the next six and a half weeks, Miller added eight more dated entries, as well as two small watercolors and a pen-and-ink sketch. The result was something more than personal correspondence and less than an accomplished narrative work: a hybrid form of literary prose we might call the book-letter. As far as we know, Miller never sought to have the book published, and the only extant copy of the text is the original manuscript now held by the Berg Collection at the NYPL.

Edgar had come to Paris in 1930 or 1931, ostensibly to paint, and probably met Miller sometime during the first half of 1936. At twenty-nine, he was fifteen years Miller’s junior. Edgar soon joined the coterie of writers and artists who congregated around Miller’s studio at 18 villa Seurat. His interest in Zen Buddhism, mysticism, Theosophy, and the occult apparently helped energize Miller to embark on his own spiritual pilgrimage, and to articulate what he discovered there in his writing. “I feel I have never lived on the same level I write from, except with you and now with Edgar,” Miller confided to Anaïs Nin. Miller left Paris in May 1939. Edgar eventually returned to the United States as well. Though the two men seem to have stayed in sporadic contact, they probably never met again. Except for a single letter from Miller to Edgar written in March 1937—a carbon copy of which Miller saved until the end of his life —no correspondence between them is known to have survived.

—Michael Paduano

March 17, 1937

Saint Patrick’s Day

In the past I had many conversations, many discussions, with others—and they were very important events in my life, and perhaps too in the lives of these others. Nothing is left of them but the aroma, the fragrance, the aura. They are in my blood, these heated conversations, but they are impossible to recall in any substantial form. If I make herein some feeble attempt to preserve the flame of our conversations it is partly for your own benefit, mon cher Edgar. I write these notes in anticipation of the day when you will open this little volume and marvel at your own lucidity, your own wisdom.

In talking to you I see always before me a man desperately seeking his own salvation. It is this primarily which has brought me back to you for renewed bouts. For in watching your struggle, in assisting at your salvation, I have taken strength and courage myself. In a way, then, all these conversations in the past, made so vivid now by our recent ones, had the same quality—that of vital exchange. As I listen to you, or even listening to myself, I hear again the themes which only under these auspicious circumstances are brought to light. The eternal themes because the problems are eternal. No, Edgar, make no mistake. We solve nothing. That is, no more than Socrates solved anything, or Goethe in talking with Eckermann. No more than Buddha in communing with himself under the “historic” banyan tree.

We are solving the business of solving! Therein lies an illusion which is not only satisfying, but activating.

I hear you saying often: “No, but freedom is not that at all—it is just the opposite, in fact!”

And as you burst out with it I hear the cogs creaking and the chains slipping. I hear all my other friends in the past speaking with equal conviction, equal ecstasy, in the act of discovery. I believe that in these moments a very real movement, a forward push, is made. It is for these moments solely, whether as contributor or inspired listener, that I come back to the joys of conversation, which it seems to me is an art involving spontaneous creation, or else nothing.

I see you often coming toward me out of the all-enveloping fog of the cloister, with the little notes you so frantically made in your room still clinging to the lapels of your coat. I see you coming toward me full of vital questions.

“Look, I want to ask you something …” My dear Edgar, I know you want to ask me everything. I know that, for the time being, I am playing substitute for God. And if I am giving you back now a reflection of your enthusiasms it is nothing more than the little Bible which you have created in me through the act of revelation.

So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God is schizophrenic,” as you so aptly said, only because the mind, whetted to acute understanding by the continuous confrontation of oscillations, finally envisages a resolution of conflict in a necessitous freedom of action in which significance and expression are one. Which is madness, or, if you like, only schizophrenia. The word schizophrenia, to put it better, contains a minimum and a maximum of relation to the thing it defines. It is a counter to sound with …

So where are we? Why at the “Bouquet d’Alesia,” at exactly that segment of the bar which you asked me to examine closely before answering definitively the question about “growth and decay.” In those eighty-five centimeters of the synthetic marble bar God took out his compass and drew a magic circle for us. “The bar is both alive and dead,” He said, in his usual jovial way. “Going toward death as functional concept; vitally alive as atomic compost. Alive-and-dead as bar to man and man to bar. Without extreme unction no birth, no death. Caught at 12:20 midnight in the stagnant flux of introspection … Pose another problem!”

There was a button to be sewed on the sack coat, pockets to be mended, a fire to be made. The answer today before yesterday’s questions still caught in the typewriter roller. What to do? A lait chaud tout seule! [“Just a hot milk!” A more literal translation, which Miller plays on in the following two sentences, would be: “a hot milk all alone!”] Always, when cogitating and recogitating, a lait chaud. Always tout seule when answering the final question which is for tomorrow. What happened? I mean—today? Why tomorrow. A lait chaud! Being God imposes difficulties, godlike ones to be sure. For one thing there is neither Time nor Space. Then again there are no beds, no holes to be mended. Everything moves on casters on a waxed floor. There is no end to the floor—no wall, no exit. It seems to me we are now safely and snugly at home. No, not quite either. The missing blanket is a bit wrinkled at the foot of the missing bed. God is so snugly ensconced that he begins to have imaginary, and of course very very trifling but very very real aches and pains. He is like a sound and healthy man with an amputated leg just before the winter rains set in. He wants a real leg so that he will have an excuse for complaining. Now, as every scientist will tell you, the real leg, of course, is in the brain. That’s why it can hurt even when it’s missing. But God has no arms and legs, neither has he a brain, so the difficulty must lie elsewhere. It lies exactly, if my memory serves me right, a league and a half northeast of Neptune. The only real difficulty here, however, is in distinguishing north from south, and east from west. God knows that Himself, even though he is without a brain, and that, that alone, is the reason why He is troubled.

“Donnez-moi de la monnaie, s’il vous plaît.” [Give me some change, please.]

PLEH—not PLAY.

Home with Expression and Significance … The lucidity of Keyserling is amazing. (The fire could be a little brighter, even if not warmer.) So is it with Krishnamurti. What was that again about Memory—the unlived residue? Or some such thing. (Wonder if that bugger Henry Miller is starting another volume of work.)

No, often Henry Miller is already in bed planning the next day’s adventure. Henry has the faculty of knowing when to call it a day. He says ofttimes, just before falling off to sleep, “if I croak during the night it will be perfectly all right.” Dying peacefully with his boots on. That’s the way Henry takes it. You can do more than just so much each day, but on condition that you lose no time thinking about it.

Just so I make a sort of mental and spiritual progression each time I meet you and we have it out. I learn by your mistakes and am fortified by your discouragement.

You profit then by your friend’s misfortune? Oui, c’est ça! Je ne me blame pas. Content, très content, moi. Tout s’arrange dans la vie pour quiconque sait d’en profiter. Je ne me trompe jamais. Toujours droit et en avant. Avant et après—il n’y a que ça. Bien sure, il y a aussi des hypothèques—c’est à dire, des ennuis. Comme c’est beau, les ennuis! Comme la pluie septentrionale! La terre tourne. Et nous aussi. L’on tourne en place. Chaque minute compte. Chaque minute fait quelque chose irremédiable. C’est bon, ça. Tout juste. La vie se présente à nous en mille aspects. Chaque aspect a son valeur, son moment, pour ainsi dire. Faut en profiter. Il n’y a pas à plaindre. Faut jouir. Faut faire l’amour avec les sacrés moments qui sont vraiment sacrés. C’est tout, mon ami. Absolument tout. Pourtant, il y a quelque chose à ajouter … C’est pourquoi je ne m’arrète pas. Je continue … Je laisse la parole à Dieu. Il sait beau parler. Son métier, quoi! [You profit then by your friend’s misfortune? Yes, that’s right! I don’t hold it against myself. I’m content, very content. Everything in life works out for whoever knows how to enjoy it. I never make a mistake. Always straight and onward. Before and after—that’s all there is. Of course, there are also debts—that is, hassles. But what beautiful hassles! Like septentrional rain. The earth rotates. And so do we. We rotate in place. Each minute counts. Each minute is something irrevocable. It’s good that way. Just right. Life presents itself to us under a thousand aspects. Each aspect has its own value, its moment, so to speak. You have to enjoy it. There’s nothing to complain about. You need to have some bliss. You have to make love with sacred moments which are truly sacred. That’s all there is to it, my friend. That’s absolutely everything. And yet, there is something more to add … That’s why I don’t stop. I keep going … I give the floor to God. He knows how to speak beautifully. It’s his job!]

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The word was not a noun, or an adjective, or a preposition, or a conjunction (quel horreur!), but it was a Verb. You can see how God must be in the Verb—it’s so perfectly natural, so spontaneous and autochthonous. God does not come home each evening, after a hard day at the factory, and knock out words. Ah no! Pas lui! Il sait mieux faire que ça. [Ah no! Not him! He knows better than to do that.] You see, God doesn’t permit himself to get fatigued. He is awake twenty-four hours of the day, and each day he is becoming more and more wide awake. It’s his nature to be that way. Homer nods now and then—God never! Voila une petite différence très impressionante. Faut pas ignorer cela. [This little difference is very striking. Don’t overlook it.]

Et comment ça se fait que le bon Dieu ne s’endort jamais? [And how is it that the good Lord never falls asleep?]

Parce-qu’il se mefie de tous les mots qui ne sont pas des verbes. De preférence il se sert du “present participle,” comme on dit en anglais. Oui, il n’aime pas beaucoup le passé parfait, ni le subjonctif. Il se dit toujours = en anglais naturellement = “I am doing this … I am doing that … I am having a good time.” Oui, il rigole tout le temps. Il ne sait jamais ce que se sera demain, ni ce que s’est hier. Oui, un drole de type, lui. Il s’en fout toujours. [Because he is suspicious of all words that are not verbs. He prefers to use the present participle, as we say in English. Yes, he doesn’t really like the past perfect, nor the subjunctive. He’s always telling himself = in English, naturally = “I am doing this … I am doing that … I am having a good time.” Yes, he’s always joking. He never knows what it will be tomorrow, nor what it was yesterday. Yes, he’s a funny guy. He never gives a damn.]

Et pourtant, il fait du progrès. Oui, c’est merveilleux ce qu’il a fait dans le temps—sans vouloir rien faire. L’on se demande parfois s’il l’a bien fait pour lui-même, ou pour nous. Moi je crois qu’il a fait tout pour lui-même. Je crois, moi, qu’il est tout à fait narciste. “L’univers, c’est moi!” il se dit toujours. Et il a raison. Parfaitement raison. Il s’y connait, ce type là. [And yet, he makes progress. Yes, it’s marvelous what he’s accomplished in time—without wanting to do anything. One sometimes wonders whether he has done it for himself, or for us. Personally, I think he’s done it all for himself. I think he’s a complete narcissist. “I am the universe!” he’s constantly telling himself. And he’s right. Perfectly right. The guy knows what he’s talking about.]

Mon cher Edgar, tu te connais, toi aussi. Mais, permettez que je vous pose une toute petite question: est-ce que tu t’y connais aussi? C’est une constatation qu’on fait rarement. L’on ne se pose pas des questions pareilles. Mais on a tort. La santé morale n’est rien d’autre que les réponses automatiques à ces question intimes. Donc, pour mettre fin à cette partition francaise je me pose une question intime. “A quoi ça sert, toutes ces ruminations vagues et elliptiques?” [My dear Edgar, you, too, know yourself. But allow me to ask you one little question: do you also know what you’re talking about? It’s an observation that is rarely made. One doesn’t ask oneself such questions. But that’s a mistake. Moral health is nothing other than the automatic responses to these intimate questions. And so, to bring this French partition to a close, I ask myself an intimate question. “What’s the point of all these vague and elliptical ruminations?”]

Je suppose que cela m’amuse. Voila! [I suppose it amuses me. Voilà!]

Edited and translated by Michael Paduano.

From The Book of Conversations with David Edgar, out from Sublunary Editions in May.

Henry Miller (1891–1980) grew up in Brooklyn before eventually moving to Paris. It was there that he made the acquaintances that would bring about the publication of a remarkable run of books, including Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, and Black Spring. Those early books, Tropic of Cancer in particular, drew intense criticism for its sexual candor and explicitness, leading to a landmark obscenity trial when it was finally published in the United States by Grove in 1961. He eventually settled in Big Sur, California, where he continued to write and paint until his death in 1980.

Michael Paduano is a Canadian scholar and archivist. He has contributed prefaces to new French-language editions of Miller’s The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy (Éditions Bartillat, 2022) and Quiet Days in Clichy (Éditions Bartillat, forthcoming), and is editor of the volume Imperfect Itineraries: Literature and Literary Research in the Archives (Éditions de l’Université de Lorraine, forthcoming). He is currently working on an extensive archival-based study of Miller’s creative process. He lives in Paris.May 3, 2023

On Butterflies

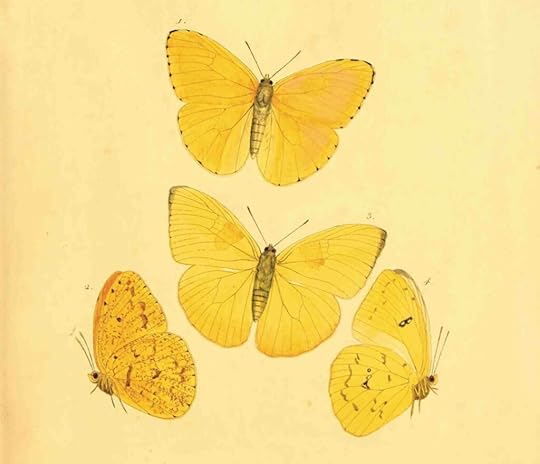

Jakob Hübner. Mancipium Fugacia argante, 1806.

Everything we see is expression, all of nature an image, a language and vibrant hieroglyphic script. Despite our advanced natural sciences, we are neither prepared nor trained to really look at things, being rather at loggerheads with nature. Other eras, indeed, perhaps all other eras, all earlier periods before the earth fell to technology and industry, were attuned to nature’s symbolic sorcery, reading its signs with greater simplicity, greater innocence than is our wont. This was by no means sentimental; the sentimental relationship people have with the natural world is a more recent development that may well arise from our troubled conscience with regard to that world.

A sense of nature’s language, a sense of joy in the diversity displayed at every turn by life that begets life, and the drive to divine this varied language—or, rather, the drive to find answers—are as old as humankind itself. The wonderful instinct drawing us back to the dawn of time and the secret of our beginnings, instinct born of a sense of a concealed, sacred unity behind this extraordinary diversity, of a primeval mother behind all births, a creator behind all creatures, is the root of art, and always has been. Today it would seem we balk at revering nature in the pious sense of seeking oneness in manyness; we are reluctant to acknowledge this childlike drive and make jokes whenever reminded of it, yet we are likely wrong to think ourselves and contemporary humankind irreverent and incapable of piety in experiencing nature. It is just so difficult these days—really, it’s become impossible—to do what was done in the past, innocently recasting nature as some mythical force or personifying and worshipping the Creator as a father. We may also be right in occasionally deeming old forms of piety somewhat silly or shallow, believing instead that the formidable, fateful drift toward philosophy we see happening in modern physics is ultimately a pious process.

So, whether we are pious and humble in our approach or pert and haughty, whether we mock or admire earlier expressions of belief in nature as animate: our actual relationship with nature, even when regarding it as a thing to be exploited, nevertheless remains that of a child with his mother, and the few age-old paths leading humans toward beatitude or wisdom have not grown in number. The simplest and most childlike of these paths is that of marveling at nature and warily heeding its language.

“I am here, that I may wonder!” reads a line by Goethe.

Wonder is where it starts, and though wonder is also where it ends, this is no futile path. Whether admiring a patch of moss, a crystal, flower, or golden beetle, a sky full of clouds, a sea with the serene, vast sigh of its swells, or a butterfly wing with its arrangement of crystalline ribs, contours, and the vibrant bezel of its edges, the diverse scripts and ornamentations of its markings, and the infinite, sweet, delightfully inspired transitions and shadings of its colors—whenever I experience part of nature, whether with my eyes or another of the five senses, whenever I feel drawn in, enchanted, opening myself momentarily to its existence and epiphanies, that very moment allows me to forget the avaricious, blind world of human need, and rather than thinking or issuing orders, rather than acquiring or exploiting, fighting or organizing, all I do in that moment is “wonder,” like Goethe, and not only does this wonderment establish my brotherhood with him, other poets, and sages, it also makes me a brother to those wondrous things I behold and experience as the living world: butterflies and moths, beetles, clouds, rivers and mountains, because while wandering down the path of wonder, I briefly escape the world of separation and enter the world of unity, where one thing or creature says to the other: Tat tvam asi (“That thou art”).

We look at the simpler relationship earlier generations had with nature and feel nostalgic now and then, or even envious, yet we prove unwilling to take our own times more seriously than warranted; nor do we wish to complain that our universities fail to guide us down the easiest paths to wisdom and that, rather than teaching a sense of awe, they teach the very opposite: counting and measuring over delight, sobriety over enchantment, a rigid hold on scattered individual parts over an affinity for the unified and whole. These are not schools of wisdom, after all, but schools of knowledge, though they take for granted that which they cannot teach—the capacity for experience, the capacity for being moved, the Goethean sense of wonderment—and keep mum about it, while their greatest minds recognize no nobler goal than to constitute a step toward such figures as Goethe and other true sages once more.

Butterflies, our intended focus here, are a beloved bit of creation, like flowers, favored by many as a prized and powerful object of astonishment, an especially lovely means of experience, of intuiting the great miracle, of honoring life. Like flowers, they seem specifically intended as adornment, jewelry or gems, little sparkling artworks and paeans invented by the friendliest, most charming and amusing of geniuses, dreamed up with tender creative delight. One must be blind or terribly callous not to delight at the sight of a butterfly, not to sense a remnant of childhood rapture or glimmer of Goethean wonder. And with good reason. After all, a butterfly is something special, an insect not like any other, and not really an insect at all, but the final, greatest, most festive and vitally important stage of its existence. As driven to procreate as it is prepared to die, it is the exuberant nuptial form of a creature that was until recently a slumbering pupa and, before that, a voracious caterpillar. A butterfly does not live to eat and grow old; its sole purpose is to make love and multiply. To that end, it is clad in magnificent finery. Its wings, several times larger than the body, divulge the secret of its existence in contours and color, scales and fuzz, a language both refined and varied, all in order that it may live out this existence with greater intensity, put on a more magical and tempting display for the opposite sex and glory in the celebration of procreation. People across the ages have known the significance of butterflies and their splendor; the butterfly is simply a revelation. Furthermore, because the butterfly is a festive lover and stunning shape-shifter, it has come to symbolize both impermanence and eternal persistence; from time immemorial, humans have embraced the butterfly as an allegorical and heraldic figure of the soul.

As it happens, the German term for butterfly, Schmetterling, is not very old; nor did all dialects use it. This peculiar word, while energetic in character, also feels quite raw, unsuitable even. Known and used only in Saxony and perhaps Thuringia, it did not enter the written language or general usage until the eighteenth century. Schmetterling was previously unknown in southern Germany and Switzerland, where the oldest and most beautiful word for butterflies was Fifalter (or Zwiespalter*), but because human language, like the language and script found on butterfly wings, is a matter not of reason and calculation, but of creative and poetic potential, a single name did not suffice and, as is the case with everything we love, language instead produced several names—many, in fact. In Switzerland today, butterflies and moths are usually referred to as Fifalter or Vogel (“bird”), with such variations as Tagvogel (“day bird”), Nachtvogel (“night bird”), and Sommervogel (“summer bird”). Given the multitude of names for these creatures as a whole (including Butterfliegen, or “butter flies,” Molkendiebe, or “whey thieves,” and a range of others), which also change according to a region’s landscape and dialect, one can imagine how many names must exist for individual butterfly species—though this will soon read “must have existed,” for they are slowly dying out, like the names of local flowers, and if not for the children who discover a love of butterflies and collecting, these monikers, many of them marvelous, would gradually vanish as well, just as many areas have seen the wealth of butterfly species die out and disappear since industrialization and the rationalization of agriculture.