The Paris Review's Blog, page 60

March 21, 2023

Ordinary Notes

Note 19

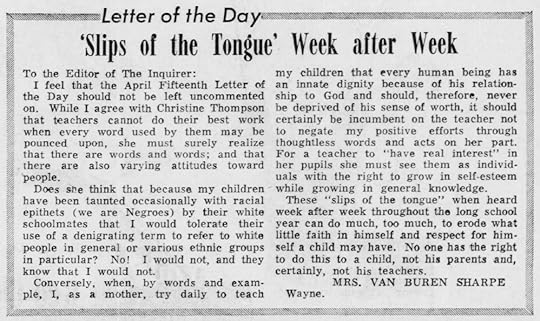

Letters to the Editor: ‘Slips of the Tongue,’ Week after Week

April 19, 1967

Courtesy of Christina Sharpe.

Note 20

Letters to the Editor: Deep-Seated Bias

December 20, 1986

If anyone has seriously been entertaining doubts that deep-seated prejudice is alive and thriving in the United States, he has only to read the December 9 front-page article in the Inquirer concerning the fourteen-year-old girl who was a rape victim to disabuse himself of this naive notion. Here we have a situation cast in the classic mold of the pre–civil rights era. A white female is raped (by a white male whom she knows) but, when describing her assailant, she does not describe a bogus white male but chooses to describe her attacker as a nonexistent black male. How sad that this fourteen-year-old child apparently instinctively chose a member (albeit a fictitious one) of another race to be her victim.

Ida Wright Sharpe

Wayne

Note 21

Letters to the Editor: Racist Asides

March 2, 1992

While I sympathize with Jack Smith’s son who was given a traffic ticket because of the flashing lights on his car (after all, are they any more distracting than the vanity plates that one tries to read in passing?), I am more concerned about the gratuitous comments made by Mr. Smith.

His remark that the car “looked as if it had just rolled out of the barrio” is blatantly racist, as is his question about the lights being “overly … Latino.” Is one to believe, as Jack Smith apparently does, that on the Main Line only Spanish-speaking individuals drive cars that have anything other than the names of universities and yacht clubs embellishing the rear windows?

I don’t know how long Jack Smith has been a resident of Wayne, but I have lived here for over thirty-eight years and can assure him that 90 percent of the individuals whom I have seen over the years getting in and out of highly decorated vehicles have been white males of assorted ages.

In the meantime, he needs to work on his racist assumptions about the other kids on the Main Line; some of them—many of them in fact—are not white and none of them deserves to be pigeonholed and disparaged by people like Jack Smith.

Ida Wright Sharpe

Wayne

Note 22

Dear Dr. Sharpe,

It has been over forty years, and this message is long overdue. My XXXXXX is in a PhD program at XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and has been reading In the Wake. XXX reached out to me because she thought I would really appreciate and enjoy it, especially because XXX noticed so many connections to schools I attended and worked for over the years. I was so proud to tell XXX we were once classmates. As you probably know, my years in grade school were incredibly unhappy, and I just wanted to let you know that you and XIXX were the only two in the class who made it bearable for me. I observed so many similar problems when I was XXXXXXX at XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX, and that is why I made the decision to leave this year. I felt like I was giving up on the school and so many students, but there are so many pervasive issues in that community, and I was sorry to see there was no appetite to make any changes.

I know we had our own adolescent issues many years ago, but I wanted to thank you for your friendship during a very lonely time in my life, and for the impact you have had on my XXXXXX.

Warm and best regards,

XXXXXXXXXXXXX

NOTE 23

And three days later, another note arrives.

Dear Christina,

You probably don’t remember me, but you have been on my mind and I finally decided to try to find you. I am XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and we went to school together. I am back living in XXXXXXX after many years outside of the area and drive by your old house frequently, reminding me of you and your mom. Having seen people from high school that haven’t changed made me wonder about the people I was really interested in, and you are one of them. I see my high school self as such a small part of what I am now, and am glad that I have rich life experiences.

I don’t know if you are ever back in the Philadelphia area, but would be interested to see you again and hear more about your life. Google is a wonderful tool, but only tells part of the story. From reading about your writing and teaching, I think you would be interested in a friend of mine from XXXXXXXXXXXX, XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX and XXX latest book. If you know XXX, even better.

Wishing you a wonderful day, and hope our paths cross in the future.

XXXXXXXXXXXX

Adapted from Ordinary Notes, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April.

Christina Sharpe is the author of In the Wake: On Blackness and Being and Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects. She is Canada Research Chair in Black Studies in the Humanities at York University.

March 20, 2023

Porn

Ryan McGinley, Fawn (Fuchsia), 2012. From Waris Ahluwalia’s portfolio in issue no. 201 (Summer 2012).

Well into my thirties, I was lucky enough to have friends with whom I could talk about anything. Anything—except the subjects of porn and masturbation. It had always been that way for me, outside of a few explosive arguments with ex-partners. The rest of the time we didn’t talk about it because we didn’t need to, because everyone was cool with it—or so our silence seemed to be saying. Except I was fairly clear that beneath this facade, I wasn’t cool with it—I’d almost never had conversations about porn, and because I hadn’t worked out my feelings and thoughts, I felt terrified to even begin. This seemed to indicate that I needed to bite the bullet and talk about it, and I imagined that other people probably did too.

So, over the course of 2020, when many of us were at home, I began to speak with friends and acquaintances on the topic of porn, recording and transcribing our conversations. Initially, I thought that if I published the chats at all, I would somehow incorporate them into essays—a safer and more literary and urbane strategy. Over time, I came to understand that these were conversations that needed to be presented as they were—in part to convince other people of the benefits of speaking about porn, and to give an insight into what those conversations could actually look like in practice. What follows are extracts from three of the nineteen porn chats I had.

ONE

A gay man in his early thirties. He lives in the United States, and is currently single.

What is good porn for you?

Good porn is no longer than twenty minutes long. Not to be overly virtuous, but I think that a lot of the porn I watched in the past—and probably the porn a lot of people consume—is pretty crappy and unethical. I’ve been interested in the idea of finding more ethical porn, less problematic porn. There’s more ethical stuff for straight people, a few sites. I’ve found a lot fewer for queer stuff, weirdly.

What would ethical porn look like?

Porn that’s less about cum, more about intimacy. Less about these “sexual scripts” that seem to be a really tried-and-tested formula for what sex looks like when visualized. I’m less comfortable watching some of the stuff I used to watch because I feel like it’s programming me or it has programmed me and will continue to program me if I continue to consume it.

Reinforcing scripts about what sex should be like?

Absolutely, and about what bodies are attractive. The only way for me to really move beyond some of that generic shit that a lot of us assume is normal is to stop consuming it on a daily basis. Anything that I’m engaging with on a daily basis is going to mark me in some way. I’m not sure that watching problematic porn, even with a critical lens, is the answer for me.

Have you observed the way these scripts impact you?

Definitely. The annoying thing is, I’m aware of the scripts but there’s still something that draws me to certain formulas, because I’ve watched thousands of porn videos where you can guess what’s going to happen, step by step by step. You can guess who’s going to be in it, the types of bodies that they’ll have. I was going to say that’s definitely changing, but I don’t even know if it is. Go on Pornhub and it just still seems to be the same stuff. If anything, there’s a bit more aggressive stuff on mainstream sites than ever.

Do you know what the part of you that’s drawn to the scripts wants?

Familiarity. The predictable is comfortable. It gives people a blueprint. It gives me a blueprint. It’s useful knowing how other people see the world, what other people expect in sex, what other people enjoy in sex. I think a lot of my ideas about what my hypothetical partner might enjoy used to come from seeing how people in porn react to people doing certain things. Like, Oh, that person in the video seems to really enjoy a finger up their arse. Then it becomes, Do I even like fingering or do I just think my partner might enjoy it?

And then, Do I know that they are actually enjoying it or are they performing this enjoyment because they also watch porn and think they should be enjoying it?

Are we just acting out porn every time we have sex? Are we just watching porn and then recreating it? Where’s the enjoyment? Where’s the actual pleasure? It’s so easy to go into autopilot and forget how fun sex can and should be.

Do you feel like the stage at which you start watching porn and the way in which you watch it is important in this? Does it matter whether your first encounters with sex are IRL or through porn?

Is anyone having sex before they’ve watched porn?! I’ve got this really vivid memory of being a young teenager—me and my friends at this particular train station with a news kiosk on the platform. You’d wait for a train to pull up to the station, and you’d time it right so that you could grab the porn magazines from the kiosk and run for the train. Some weeks we might do it more than once. That was where my consumption of sex began, because that was my first interaction with porn. It was theft and it was on a train platform and it was part of this heist.

Would you then take the magazines home?

I would and I’d be confused by all these boobs. So many boobs. Being a gay boy but still thinking to myself, I’m meant to like this, all of my friends like this, why don’t I like this?

As a gay boy looking at those straight porn magazines, was there enough male presence in there to be stimulating or was it all women?

It was basically all women. On some level, I was always searching through the pages to see stuff where women were interacting with men, and I don’t think I often found what I was looking for. Most of the people reading them don’t really want to be confronted by a dick. I preferred the images where there were men and women, but I never got into straight porn—it never made much sense to me, so I had a big period in my teens where I just didn’t watch porn. When I realized what homosexuality was, I didn’t switch to gay porn—that felt too scary. I just had no porn.

It felt too scary?

Being unsure about who I was then, consuming gay porn at that point might have tipped me over the edge. A gateway drug. Catholic schooling, through and through.

So what was it like when you eventually started watching gay porn?

It felt right and wrong at the same time. It felt right because I could tell I was more excited about what was going on, but it felt wrong in that it was so tied up with feeling uncomfortable in that identity and in my skin at the time. Once I started watching it, I couldn’t stop. It’d be daily consumption, in secret, with headphones on, blinds closed, when nobody else was home. It was a real shame cycle. Instant feelings of real aversion after I’d finished—clear browsing data, clear cookies, clear cache, whatever that even is. And my relationship with porn was really marked by that almost immediate feeling of discomfort after. I don’t know what motivated me to continue to watch porn, but I wouldn’t say it was pleasant.

At that time, all the bodies seemed identical—masculine-appearing men, having sex with what looked like their siblings. They were mainly white, everyone had abs, and all the bedrooms were the same. It was as if every studio had one bedroom and they just went in and used that one space.

Did you have a clear sense of what was missing or was it a sense of, This is what porn is?

I went as far as saying, This is what sex is. Sex is intercourse between models. I didn’t even start to think about what other people who didn’t look like that would be doing—maybe reading, or watching TV, but not having sex. Sex was for skinny, attractive, masculine men, at least in my consumption of gay stuff. That was partly because I probably wasn’t doing that much looking around. I went to the mainstream sites for gay porn because I didn’t really want to be online searching through lots of different stuff. I had it in my head that if I got too exploratory, that would be how I got caught, and I couldn’t get caught.

That sounds like a very powerful script to be going into sex with. Did it make your first real sexual encounters quite difficult?

It didn’t, because it made me very selective about whom I would have sex with. I went on to perpetuate those ideals in my sexual partners. The first few guys I slept with were all tall, built, and more masculine. It took a while to unlearn all of that. I’m still unlearning it.

Would you say that unlearning process was conscious?

More recently, it’s been conscious, to do away with the ends of that. I still have to regularly remind myself of basic shit that I’ve got to learn. I realized that being with someone conventionally attractive doesn’t have anything to do with their personality. It doesn’t mean they’ll be nice. It doesn’t mean they’ll be funny. I was dating people because I thought they were “hot” and realizing, Hold on a second, we have nothing in common. I don’t even think I realized I was unlearning it. I was just connecting dots and realizing that whatever gauge I was using to pick people whom I thought I was interested in just wasn’t working. It’s not easy looking back on my behaviour.

When I started learning how to date in my twenties, I’d gravitate toward masculinity.

I appreciate the scare quotes around “hot.” I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wanting to find your partner attractive, and potentially that is something that you have to weigh up against them being a nice person. But I’m fascinated by “hotness” as received message, as social capital—how much do you think they’re hot because you think they’re hot, and how much do you think they’re hot because society has told you to think they’re hot? It’s easy to stand on your high horse and say, No, no, no, this is my personal taste, it’s nothing to do with social pressures, but it’s only once you start that process of unlearning, intentional or not, that you realize, Okay, no, I’m much more affected by these standards than I thought I was.

If the porn I was watching when I first found gay porn featured people with size 38 jeans, then the people I would’ve been drawn to when I first started dating would’ve looked different. Obviously, it’s not just porn—a lot of industries are to blame for how skinniness is so prioritized across genders. But fuck me, there aren’t many things that teenage boys consume on such a regular basis during that critical period of identity formation. It’s like learning a language. That’s what I was doing—I was learning a language of sex. I do want to watch more porn, I’ve realized. I just don’t know where to find it anymore. Of course this is not practical at all, but sometimes I think that the type of porn that I want to watch, I’d have to make or direct myself.

Have you ever felt that prospective sexual partners’ expectations of you are shaped by the porn that they’re watching? Are there special expectations that attach to you as a Black man?

Yeah, absolutely. Before I came out, whenever I interacted with women, there was an expectation that I’d be very masculine, very dominant and aggressive, and in fact, that’s pretty similar with men. That’s been my experience navigating the world through heterosexuality and navigating the world through homosexuality. A lot of people expect what they see in porn to be recreated in person, though that’s rarely explicitly verbalized. Even in relationships, I think the ideas people have gotten from porn have shaped people. Not expecting me to have an emotional anything, really. I can’t see a better candidate for what has shaped this other than porn.

That’s heartbreaking. It’s also illuminating, if not surprising, to think that what lies on the flip side of the “aggressive” stereotype is a total denial of someone’s emotional reality.

It’s not that I don’t want to be dominant sometimes. It’s just that that’s not how I always want to have sex. The expectation is that that’s where my preference has to begin and end whereas I’m like, Well, sometimes I want to be thrown around too. Being boxed in like that pretty much ended one of my earlier relationships. I’d initially accepted how fixed his views of me were, and it transferred outside of the bedroom, where he didn’t expect me to have feelings. It made me feel like a piece of meat. I’m a whole person! He wasn’t a bad person, it was just a bad fit.

Have you felt in the past like you’re being fetishized?

Definitely. There have been times where I’ve been talking to a white guy on an app and they’ve used the N-word. People have asked me if I’m into race play. There’ve been times where I’ve felt ignored. Obviously it’d be problematic to demand I get a response from everybody, but my experience and the experience of other friends of color who have navigated apps is one of being second-class citizens in that context.

For dating, or for sex as well?

I find there are more people who want to have sex with me than want to date me. For some people it can be about fulfilling a sexual fantasy, whether they say so or not, but it’s not meeting a potential partner. People are allowed not to be looking for anything serious, of course, but I’ve had the thing where someone’s not looking for something serious, so we just have sex, and then maybe a week or so later they’re in a committed, exclusive relationship with someone who looks like their sibling. I’m like, Okay, cool.

Are people ever vocal about the fact that you’re their sexual fantasy?

Oh, they’re not just vocal, they expect you to be grateful. I chatted with a guy on Tinder about it once. It was a debate more so than a conversation. It went on for hours until I realized it wasn’t my job to shift his understanding. Pouring energy into those debates is a trap for sure. If I’m just a thumbnail for someone, that person isn’t necessarily going to care about my comfort and safety during sex. So, not having certain conversations has implications for my welfare and health. I also have to remember that I’ve been watching porn for a really, really long time as well. What am I doing to people?

TWO

A queer person in their late forties. They live in Japan and are in a long-term relationship.

Is porn something you talk about with people around you?

Well, leading up to chatting with you, I went off in all kinds of directions thinking about it. I made a Venn diagram, I was all over it. One of the things that really interested me was a presumption that I’m part of a community that’s all about sex positivity and body positivity, where we happily and freely talk about various sexual things at the drop of a hat, nobody’s shy at all, et cetera. It’s not necessarily true. I’ve got these random memories of porn-related incidents or conversations in my various queer circles, and aside from those related to my partners, none of them feel really deep-down. So I was thinking, Maybe I don’t really have a relationship with porn, fuck, what kind of a queer am I? That sense of disconnect goes way back. When I graduated from university, all the cool lesbians went on a camping trip. They went in their cars up into the mountains, and for some reason I got to go with them. There was a hailstorm, it was really atmospheric. The cool liberal studies graduates were talking about sex, and one girl, whose cool mechanic girlfriend Dusty was right there with her, was saying, I just got Dusty to let me touch her perineum for the first time the other day, and everybody was having this conversation. I was there thinking, Ah, that sucks for Dusty. If she hadn’t had her perineum touched before, maybe she didn’t really want to talk about it either. There’s a coolness that doesn’t always go with checking everyone’s comfort level. I’ve seen that a lot over the years—people are happy to talk about sex while also not talking about it.

I often sense that when we’re talking about things that are hard to talk about initially, such as sex and porn and intimacy, that need to be “cool” can present a barrier. There’s an echo of the way people worry about political correctness in this pressure to be pro everything.

“Well, of course we’re fine with all of this”—that becomes a given. As you say, in most circles we haven’t really got the language. That’s why those sex toy videos I emailed you about are so great: “I’m just sitting here talking in a very normal salesperson voice with a little bit of extra softness about something I’m suggesting that you’ll really enjoy putting in your anus.” The disconnect that’s there is fantastic.

When you haven’t got a language around something, how do you go about developing one? At the start of this project, I didn’t feel comfortable talking about porn or masturbation. It was absent from my life.

From your spoken life.

Exactly, from my spoken life. The distance between the discourse and what’s actually going on is odd. When we’re forming a new language, does it have to be a kind of “fake it till you make it” thing? Do you and your current partner talk about porn?

My partner is just getting over a bout of the dreaded virus. It’s been really rough, and he went away for a while to quarantine. We’ve been talking on Skype like we did back when it was a long-distance relationship, when I was still in the sheep field. Yesterday I told him, I get to do the porn chat tomorrow, and I asked him what he would say his relationship is with porn. He said that, right now, the virus has killed his libido, he has no energy for anything. The idea of sexual things right now is still up there with, um, what was it? Chilies and caffeine: things he’s not quite ready for yet. Back in the day when I was in the countryside and he was here, we would read porn to each other. Send each other little videos of readings, or read to each other live until my laptop battery ran out in the horse box. I don’t remember what came first, but there were also wanking videos sent back and forth, on memory sticks. We had our own little poor-relation Pornhub going on. I’d forgotten about it until I was thinking, Let’s see, porn, porn, porn … oh yeah, there was all of that.

Actually, we made a little video, using the videos we’d sent back and forth to each other during that time, and sent it in for an online screening of pandemic porn. I don’t know if we made it in, because it was three o’clock in the morning here when it was playing in the UK and we couldn’t get the link to work. I’ll probably die not knowing. Or maybe someone will come up to me one day on the street and say, Oh my God, was that you in the sheep field?

Do you have any anxiety around that? I’m incapable of sending people videos or nudes or anything of me, because the idea of them getting out is terrifying in quite a nonspecific way. It’s not a particular scenario based in my head. It’s just a sense that I need to not do that for fear of … something.

With unknown fears, it’s not “what if this happens”—it’s “something could happen.” But, people on the street, maybe not so much. When I was living in the city a long time ago, whoring, often I’d be thinking, What if I’m walking down the street and one of my johns sees me and says hello? How funny would that be? How weird would that be? What if someone who’s only ever seen me naked sees me now? But that wouldn’t really be any different in terms from one of my clients at the English conversation company I work at now seeing me in my not-work clothes. There are so many ways in which that work—selling my full attention and all of my words for forty-minute sessions one after another—feels more distasteful and more dishonest than selling my body for money. I’m pretty sure I think that, anyway.

Obviously the way porn and misogyny and patriarchy interact is massively tangled and anything but unidirectional, but I do find myself wondering about how porn radiates outward, in terms of shaping sexual practices and the things that people—particularly men, I suppose—want to enact in the bedroom. In your experience of doing sex work, did you see that play out, or see things that were clearly from porn?

You can’t not go there, though. That’s the dark side, right? That’s the not sex-positive or person-positive side. The truly sinful side. I was only doing sex work for maybe four or five months. It wasn’t legal, I didn’t have a visa for it. It was how I was making a living, but it was also something I had chosen to do out of interest, something I wanted to know the experience of. When I thought about it in terms of temple priestesses, say, when I went all ancient Greece fantasy with it and was like, This thing that I’m doing and this service that I’m providing for this person is holy, and if I was with someone from whom I could get that sense of gratitude for the profundity of what was going on—because some people were like that, and that was amazing—that was pretty right on. Others were very clearly not like that—some people were doing things that they wanted to try out because they’d seen them on TV, and they weren’t nice things. Or they saw it that way. You can feel it. You can feel it in any situation when somebody is not seeing you as a human being. And that really sucks when you’re naked and you’re sucking their dick.

Did you have a sense before you got to the being naked and sucking their dick part—would you know which way the interaction was going to go?

There are probably a lot of people in the world who have better risk antennae than I do, but even I sometimes would walk into a room and think, Oh, this is going to be one of those. Sometimes I’d be wrong, and it would turn into something everybody could get something good out of. Other times it was just ugliness and abuse and it’s a real shame that that’s what people are capable of equating sex with. I’m sorry that I didn’t have the temple goddess strength to bring those people around. But how can anyone, really? All the ugliness is so deeply ingrained in us and so much of it is connected to not having a way to talk in a healthy way about it.

Do you think there was more ugliness because at that time you were in the bracket of sex worker in their heads? And therefore on the slut side of the slut/virgin dichotomy?

Absolutely. The commodification bit, right? If money is what I value and I can get it for money, then sure, the person doesn’t matter. That’s gross. Even if I was telling myself that it was just a job, the experience of commodification in sex work was still physical, it was going into my body, and there were unscheduled long, weepy baths on the bad days, soaking that stuff out. And that was without any of the truly bad stuff having happened. I don’t know how we fix porn, but it feels important.

It’s not just porn, though, is it? Porn has emerged from and plays into this enormous patriarchal capitalist system. And it’s so hard to imagine fixing just one part without fixing the thing in its entirety.

It’d be fine if we could fix everything.

THREE

A straight man in his early twenties. He is recently single.

Can you describe your current porn-watching habits?

It’s not something that’s set in stone. I probably watch it more in the morning than I do at night. I find that if I do it in the morning then I can just get on with my day. If I gave an estimate of how often, it varies on how I’m feeling, but say two to three times a week.

Would you ever masturbate without using porn?

I have done, but if porn’s available, then I’d probably use that. It’s more stimulating than my imagination. I’m fine with pictures, but if we’re talking videos, then these days I just use Pornhub.

What would you be watching on there? Do you go for the top-page stuff?

I’ll look through the top page first, and if there’s anything there that catches my eye, I’ll click on it. If I was going in looking and searching, I don’t search for anything too crazy, to be honest—maybe anal or orgies or something like that. Something maybe that I wouldn’t do in my own life. I don’t go out of my way too much. If there are things on the first page that aren’t too bad, I’ll watch them.

You said you tend to watch things that are things that you wouldn’t do in real life. Can you talk me through that?

Yeah, not as much with anal, because obviously I’ve done that quite a bit, but it’s not something that you do all the time. With orgies and threesomes and all that kind of vibe, it’s not that it’s taboo, but that it’s something that you don’t normally experience. So it’s living vicariously through that lens.

The full fantasy experience?

I don’t know if it’s my fantasy. I’d probably be down for a threesome, but with the orgies, I don’t think I’d actually want to do that in real life. It’s more that the chaos on screen of everything happening is quite stimulating. I wouldn’t choose to watch a porn of myself, basically, because I’ve got lived experience of that. Not that it wouldn’t necessarily be stimulating, but I think if you’re going to go to that effort, you watch something that you’re not going to do yourself.

Where do you stand on violence and rough sex—that whole aspect of porn?

Some people are into being a bit more rough, and I am as well, both watching and in my own life, but at the same time, there’s got to be limits to that. I’m not into people getting slapped in the face, or pinned down by the neck, or kicked. I get that maybe some people are, but to me that doesn’t seem enjoyable. A bit of choking and a bit of slapping is fine as long as both parties are in agreement. Whenever that is happening in real life, you talk about it first and have safe words so you know that that’s what you want. In regards to porn, even the taglines are worded in a way that fantasizes violence: “small white girl getting brutally destroyed” and stuff. I do think that porn has created a fantasized ideal in people’s heads about sex, and the physicality can bleed into people’s lives. If you’ve seen James Bond jump onto a fucking train in a film, you wouldn’t then think, I can go and do that. But with porn, even though it’s all scripted and specially cultivated in such a way that that’s what the end result is, people take it too literally, and I don’t agree with that.

How old were you when you first saw porn, and how did it happen?

My first experience of watching porn was when I was in first year, so I would’ve been about twelve. It was my dad who showed it to me. He was in this group chat and one of his pals had sent these two videos. One was just normal sex and the other was called “Super Squirter”—you can guess what happened in that. They were both short—one was maybe two minutes and the other thirty or forty seconds. He showed me them on his phone, and I was like, This is great shit, so I asked him to send them to me. Then I took them into school, showed all my pals. From there I just started searching myself—the thing with my dad is the part I vividly remember. As much as I probably wouldn’t send porn to my kids, I also think that when you do that, it opens up a dialogue. It makes a difference when you’re able to talk about the same things and you laugh and enjoy it.

Regardless of the kind of relationship you are in and how good the sex is, would you continue to use porn on the side?

It’s totally separate. It’s a means to an end, almost. Masturbating lets off steam. It’s not as if I’m choosing to not speak to you in order to go and do this. It’s when nobody’s around. But moderation’s a big thing. If I were doing it every day and it became not so much a habit as an addiction, then that’s dangerous.

Has the moderation come naturally, or is it something that you’ve achieved?

When I was younger, when I first started getting into it and falling down the rabbit hole, I was masturbating a few times a day for the full week, just thinking, Oh my God, this is amazing. Once I started having sex, though, the realization came that it’s a really different ball game. Between the ages of fifteen and seventeen, when I started having sex and understanding more what sex actually is and what’s involved, my porn usage really died down. It became more like I’m describing it now—a wee external thing for yourself. I would hate to rely on it. I’d hate it to be an end in and of itself, to think it’s better than the real thing. Maybe the first few times you have sex, it probably is. But then that brings up the question, How can I have better sex? That’s more of a task, it’s more interesting.

Do you feel that porn has helped you to know what you like in bed, and to talk about it with people?

I don’t want to give it the credit but I’m going to say yeah, I do think so. If anything, it gives you the language to explain and verbalize things. You see things in videos that make you think, That seems quite interesting, maybe I’d like that. It all comes down to doing it, but porn did help in giving me the vocabulary to be able to express it. Take how vocal people are in porn. I can’t speak for all guys, but I know that there are quite a lot of girls that aren’t that vocal in real life. I’m not talking about screaming in my ears, but just something, anything at all. That’s what gets people off sometimes, that’s what people really like. Even just moaning in somebody’s ear can go a long way. Let’s say you do see something and think, That looks good, I’d like to try that, I have the vocabulary to express that, you’ve still got to approach it with the understanding that, one, your partner’s got to be into it, and two, that it’s not going to be what you’ve seen on-screen. Even talking about it is difficult, especially when you’re younger and you’re just starting out. When I was younger, I was in bed with girls who wouldn’t take their tops off because they felt insecure. You can even go as far as having sex with somebody, and there’s still that stigma, especially when you’re in your late teens. To be able to talk about things, you have to feel comfortable. Everyone wants to talk about things deep down, but they find it difficult. Especially if it’s a newer relationship or if you’re sober, people really struggle. If you’re in a committed relationship, it becomes second nature to discuss things. If you don’t then your sex is doomed anyway. The more you do it, the more comfortable you are with talking, and if you’re comfortable then other people are comfortable. That’s the main thing: having a really good space to speak and to be judgment-free and to be like, I want you to feel pleasure, the same way I feel pleasure.

Polly Barton is a translator and writer. Her nonfiction debut, Fifty Sounds, won the 2019 Fitzcarraldo Editions/Mahler & LeWitt Studios Essay Prize. This piece is adapted from Porn: An Oral History, which was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions on March 16, 2023.

March 17, 2023

Art Out of Time: Three Reviews

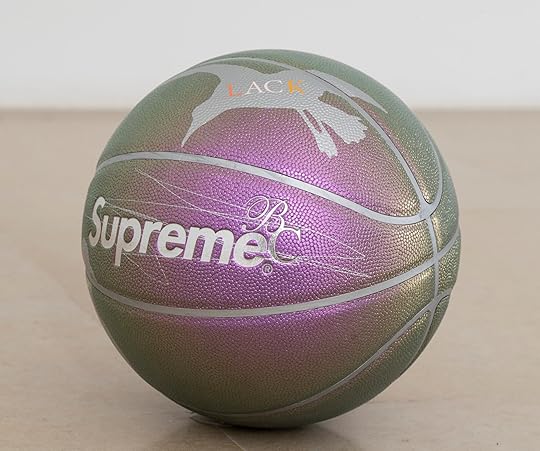

Bernadette Corporation, Untitled, 2023. Courtesy of Greene Naftali.

This week, three reviews on damaged art, art out of time, art of our time, and enjoying the void.

We’re in a particular phase of “pandemic art” now—I don’t mean work that portrays the spread of disease (I’ll leave The Last of Us to another writer) but the work that artists made while they lived in hibernation: writers at their desks with no social obligations to draw them out into the city, artists in their studios with the endless horizon of hours receding. Now they are showing what they made. Tara Donovan’s stunning “screen drawings,” on view last month at Pace Gallery in Chelsea, are a project begun in that period. The “drawings” are made from typical aluminum insect screens, cut and tweezed into intricate geometric patterns—layered lines, swirls, and cutouts—that shimmer and morph as you walk through the gallery. They are subtle optical illusions cut from the humblest everyday material. Their connection to the period of “high quarantine” strikes me immediately: time spent looking out the window onto silent streets, time spent feeling intensely aware of the need for protection. The discourse around “screen time” is of course fatiguing, but Donovan’s drawings for me reinvigorate the multiple meanings of the phrase. Before we came to understand the screen as the portal that brought the outside infinity into our personal space, screens were more often for keeping something out: a fugitive look, a bothersome fly. (I saw Donovan’s work around the same time as I became aware of an interesting but disquieting TikTok trend of overlaying TV clips with ASMR videos, in case you didn’t have enough stimulation.) What else do they continue to separate from us? A special quality of Donovan’s manipulations is that no photo of them can do them justice—they look good in two dimensions, but in person they are almost hypnotic in their immersive power. They’re hardly capturable as digital artifacts, and so much the better.

—David S. Wallace, contributing editor

Going eight floors up the elevator at Greene Naftali on my lunch break and out into the open white space that recently housed the gallery’s Bernadette Corporation exhibition felt a lot like walking into God’s office on his break from Creation: there were whiteboards covered with half-assed frescos and half-erased flowcharts; pennies, some stacked neatly, others laid out in the shape of man; on the white plinths supporting them, more doodles of equations, apples, and names begun and then abandoned. It all connects, of course, somehow—this stuff, these ideas. The scribbles suggest motion and relation, formal analogies (between pie charts and pennies, currency and chemistry), but the forces of association seem to give out halfway. The only thing left whole was an oil-slick-iridescent Supreme-branded basketball, spherical and sparkly, that seemed to have bounced straight out of those equations and onto the floor. God must have gotten bored setting up gravity, orchestrating economies, making paintings, and doing anti-capitalist art critique. But he still likes to play—and shop. The effect, difficult to execute and surprisingly lovely, is of a beautifully bad throw of the ball: an immaculate weak gesture, conceptually and aesthetically. I didn’t mind; such are the times. If I were God I’d take a break, too. Sunlight still flooded the mostly empty room. I wished it had all been even weaker, that there’d been couches and a coffee machine, to make the art recede even further into the scene of the God-office/gallery, and to make it easier for me to sit around and play on my iPhone. The show closed last weekend, but that’s okay. Its brilliance is that it was only half-there to begin with. You can still go answer your emails on the eighth floor of Greene Naftali on your lunch break if you work in Chelsea.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

Lately, I’ve been rereading Molly Brodak’s 2020 poetry collection The Cipher. I first read it more than a year ago and have found myself returning to it ever since, whenever I’m in need of a line to carry me through the day. This time, I’ve been drawn to moments when opulent, lush textures adjoin absences or voids. There’s the extravagant feast of “The Babies,” for example, rendered in exquisite detail but forbidden to eat. In “Axiom,” a cloth of yellow silk enfolds the empty space where the Ark of the Covenant would be kept, were it ever recovered or had it ever even really existed. The guard at the door watches over an empty chamber containing only the silk, and, at times, a ray of light. Describing the inspiration for her poem “The Flood”—which describes a Paolo Uccello fresco of the Noah’s Ark, which has itself been damaged by a real flood—she writes: “I don’t know if I would like the painting as much if it hadn’t been damaged. It is another painting now.” This reminds me of another one of her lines, from “Conversation”: “I imagined / a bolt of pink waterstained silk / in place of me, being / loved.” It is a marked object—textured with the evidence of utility, accident, or event—with which Brodak chooses to represent herself. In her work, things that change are never ruined; they are merely renewed as variations on themselves.

— Leena Mahan, reader

March 16, 2023

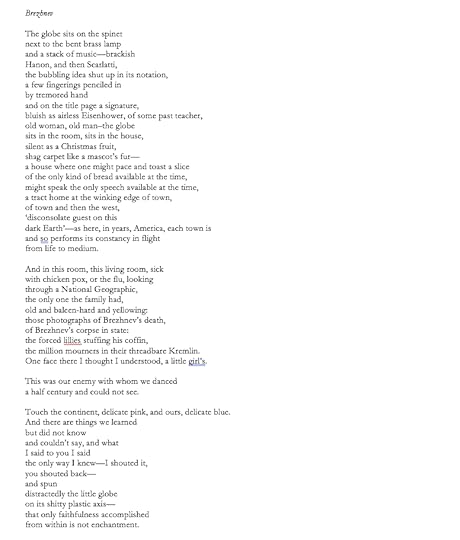

Making of a Poem: Timmy Straw on “Brezhnev”

Courtesy of Timmy Straw.

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Timmy Straw’s “Brezhnev” appears in our Winter issue, no. 242.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

There’s a scene I used to picture a lot as a little kid in the eighties—two people dancing slowly, closely, their bodies seeming to know and anticipate each other, only they are also separated by a screen, so that neither has ever seen the other’s face. This was, I think, one way I understood the world at that time. This dance (so I imagined) is what formed reality itself—Reagan’s America, Gorbachev’s Soviet Union—and the dancers’ mutually blind position was like an engine, driving the world on. This made-up scene, and my adult memory of it, was certainly a major goad to the poem. So was a weird little detail—one of my older brothers could never understand that my one-year-old self was not, in fact, a teenager like himself, and so would read to me from The Annals of Imperial Rome and the most turgid high school astronomy textbooks. Because of his mania for geopolitics, he also taught me how to say “Brezhnev”—so that, awkwardly, the Soviet general secretary’s surname was one of my first words.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? Are there hard and easy poems?

“Brezhnev” was written in late lockdown, at a point when I’d taken to swimming a lot—I had some vaguely science-y conviction that the massively elevated public-pool chlorine levels would be incompatible with covid. I liked to work out poems in the pool (in my head—no waterproof paper was involved), and the first draft of “Brezhnev” had something in it of the satisfying pull of a solid hour of the Australian crawl. It was spookily easy to write, maybe because it is largely narrative, even a little cinematic. The sense was less of pursuing a new poem, with all its hidden laws and strange hostilities, than of becoming increasingly interested in the sequence of images appearing in front of me. In fact, when the first draft was done, reading it back felt a little like looking at a VHS film on pause—the tension and blur of the vibrating image.

But yes, there are definitely poems that are quick to write and poems that can take years! I’m thinking of a poem (“The Thomas Salto”) that started in 2016 and then proceeded through probably fifteen-plus inadequate iterations over six years before arriving, last year, at something I can live with. Poems begin like migraines do, I think, and you get rid of them with similar rigor—albeit not with aspirin, quiet, and a dark room, but by writing and writing them down until they go away (hopefully into their completedness, most often into their failure!).

What were you listening to / reading / watching while you were writing this?

I was reading an essay by the Russian poet Olga Sedakova called “Mediocrity as a Social Danger.” In it, she quotes this luxuriously doomful line from Goethe, which I lifted—“You are a disconsolate guest on this dark Earth.” Sedakova’s essay is audacious, lucid, problematic, and sometimes surly. (At one point she notes, by way of a casual aside, that human will can be summarized as follows: “to ask for or refuse a drink, as on the cross.” To which I reply, Yikes! But also, minus the Christian referent … maybe.)

I was also listening to a lot of Bach (Varvara Myagkova’s recordings of the preludes and fugues) and to Future’s “Mask Off” (the remix, with Kendrick Lamar). I like to think these songs had an effect on the poem’s form on the page, the way interstitial words like and or some are accented through the quickness and harshness of the line breaks—I was particularly wanting to get some of the bare and almost dingy beauty of the counterpoint in Bach’s Fugue in E minor from Book 1, and the skittering play of the snare against Kendrick Lamar’s verse on “Mask Off.”

What was the challenge of this particular poem?

“Brezhnev” is expressly autobiographical, which is not a kind of writing I generally do, and I find it a little scary—not for reasons of “vulnerability” but because such writing is embedded with the impossible imperative to “get it right.” By “getting it right” I mean being true to the dignity of the people—in this case, my family—whom I’ve dragged into the poem, and who know very well the place and time and circumstances of which “Brezhnev” is a (smudged) mirror. If a poem is explicitly autobiographical, then by rights it exists not only for the sake of itself but for the actual, named people in it—i.e., people whom I love and who, while “in the poem,” are also at this very moment out there on earth, doing and thinking and feeling things. All this made me nervous, and so, while the first draft came quickly, I fiddled with subsequent drafts for ages.

I also spent a lot of time sorting out its form—in writing “Brezhnev,” I had begun working in this new way, breaking the line according to a predetermined margin setting such that the emphasis lands, sometimes aggressively, on words that bear no meaning in themselves (and, the). This skews the attention, I think, toward operations and functions in the poem and away from people and things (sort of like shining a spotlight not on the actors and props but on, say, the electrical outlets on the stage floor). I also wanted the poem on the page to invoke a cat’s cradle—the kids’ game that thematizes, with great simplicity, the notion that if you tug on one thing, everything moves. A pretty good summary of Cold War geopolitics, and, I guess, of our own historical moment.

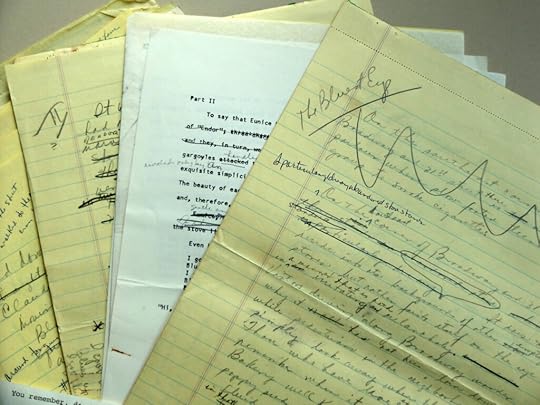

Do you have photos of different drafts of this poem?

I don’t usually keep drafts around, partly out of laziness and partly because I don’t want to look back and turn into a pillar of salt, but I do have an early draft of “Brezhnev.” You can see the three long stanzas, with a couplet overdramatically wedged in there toward the end, plus some unnecessary exposition, the first bit of which I had the wherewithal to remove. The last bit (the final six lines), however, I kept, until Chicu [Srikanth Reddy, the Review’s poetry editor] wisely suggested I redact it. I had wanted a denouement, some pleasing display of concluding truth (whatever that is); but he saw something far more interesting—the torque achieved in its refusal.

An early draft of “Brezhnev.”

Timmy Straw is a poet, musician, and translator. Their poems “Brezhnev” and “Oracle at Dog” appear in our new Winter issue, no. 242.

March 15, 2023

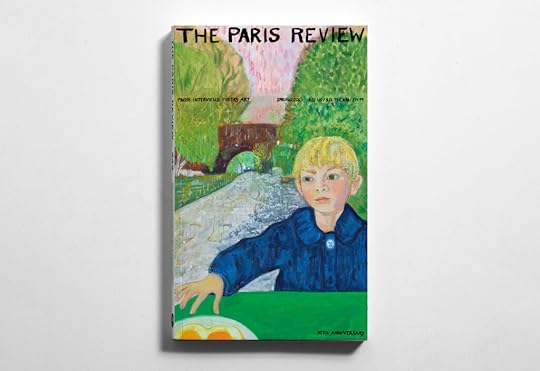

The Review Celebrates Seventy with Fried Eggs by the Canal

Peter Doig, Canal Painting, 2022–2023, on the cover of issue no. 243. © Peter Doig. Courtesy of the artist and TRAMPS; photograph by Prudence Cuming.

For the cover of our seventieth-anniversary issue, we commissioned a painting by the artist Peter Doig, of a boy eating his breakfast beside a London canal. Our contributing editor Matthew Higgs spoke with Doig about his influences and fried eggs.

INTERVIEWER

How did the cover image come about?

PETER DOIG

I’d made a birthday card for my son Locker—a more cartoony version of what became the painting. I quite liked the subject: he’s sitting at a café on the towpath of the canal in East London. Everyone who knows London knows the canal—we take it for granted. I can’t think of any paintings of it, but it seems to me a sort of classic painting subject.

I started working on the image alongside a big painting I was making for an exhibition at the Courtauld. I was thinking about how my work relates to the Impressionist galleries there, which contain Cézanne, Gauguin, Daumier, Van Gogh, Seurat, et cetera. I had begun many of the paintings before I was invited to make the exhibition, but most of them had a long, long way to go before being finished. I’d brought all my paintings to my London studio from New York and Trinidad, and all of a sudden I had more paintings in progress than I think I’d had in probably thirty-odd years. It was quite exciting in a way, but then I had to make an edit, to decide which ones I was going to concentrate on, because I was getting carried away and I was never going to finish everything. The canal painting was the one very, very new one. That’s why I liked it for the Review—and because, although I thought of the image as very much a London painting, somehow after I made it I was reminded of Paris, and of French painting more than of English painting.

INTERVIEWER

Is it important that the viewer knows the boy is your son?

DOIG

Perhaps for people who know him. I’ve got quite a large family, and so it’s important to me that when I make a painting that depicts one of my children, the others can relate to it and feel that they understand why I did it. In the painting of Locker, I wanted to capture a person at that stage in life, the way Cézanne did when he used his son as a model. Another one of the paintings in the Courtauld exhibition features my daughter Alice in a hammock surrounded by greenery. I began working on the painting in 2014—I know that because I recently found a photograph of Alice standing in her primary school uniform looking at it when I very first started it. I finished it this year in my studio in just a few hours, after having returned to it after all those years. One of my other kids saw it and said that I had absolutely captured Alice at that age. That’s why I left it not quite finished, with translucent tones—I wanted it to feel almost ghostly. She’s now a grown woman, and it captures the passage of time.

INTERVIEWER

What’s the significance of the canal?

DOIG

The canal, up until fairly recently, was a place of dread. After the industrial revolution, the canal no longer served the buildings on it, so for a long time stepping onto the towpath at night meant risking a mugging or worse. That has changed and is changing. The painting’s setting is a real café very close to where we live at present, and where I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the last few years, looking westward at the view through the bridge. Sitting there I realized how beautiful it is, and how much like a painting it is already. I also thought of paintings by Manet and others—paintings of railways and train stations, with figures in the foreground.

INTERVIEWER

The Impressionists painted some of the earliest depictions of what we understand as modernity.

DOIG

I was looking at Manet’s painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Behind the girl at the bar, there are two globes in the background, two spheres. It’s not obvious at first, but they are electrical lights, and Manet painted them in very, very sharp focus, whereas everything else in the painting is quite blurred. I suppose at the time Manet made the painting the viewer would have been really surprised by this very modern element entering a work of art. In my painting, the eggs are a bit like that—in a way, the eggs are the most contemporary thing in the painting.

Matthew Higgs is a contributing editor of The Paris Review.

March 14, 2023

Camus’s New York Diary, 1946

Camel cigarettes billboard in Times Square, 1943. Photograph by John Vachon. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

March 1946. Albert Camus has just spent two weeks at sea on the SS Oregon, a cargo ship transporting passengers from Le Havre to New York City. He’s made several friends during this transatlantic passage.

Sunday. They announce we’ll arrive in the evening. The week passed in a whirlwind. Tuesday evening, the twenty-first, our table decides to celebrate the arrival of spring. Alcohol until four in the morning. The next day, too. Forty-eight hours of pleasant euphoria, during which all our relationships quickly deepen. Mme D. is rebelling against her class. L. confesses to me the marriage she’s headed for is one of convenience. On Saturday, we exit the Gulf Stream, and the temperature turns awfully chilly. Nevertheless, the time passes very quickly, and ultimately, I’m not in such a rush to arrive. I’ve finished preparing my talk. In the remaining time, I gaze out at the sea and chat, mostly with R., who’s really quite smart—and with Mme D. and L., of course. At twelve in the afternoon, we catch sight of land. Seagulls have been flying alongside the boat since morning, hanging above the decks as if suspended and motionless. Coney Island, which looks like the Porte d’Orléans, is the first thing we see. “It’s Saint-Denis or Gennevilliers,” L. says. It’s absolutely true. In the cold, with the gray wind and flat sky, it’s all rather gloomy. We’ll anchor in the mouth of the Hudson but won’t disembark until tomorrow morning. In the distance, Manhattan’s skyscrapers stand against a backdrop of mist. My heart is still and cold, as it is when faced with sights that don’t move me.

***

Monday. Went to bed very late last night. Got up very early. We sail through New York Harbor. A tremendous sight despite, or because of, the fog. Order, power, economic strength, they’re all here. The heart trembles before so much remarkable inhumanity.

I don’t disembark until eleven o’clock, after a long series of formalities where, out of all the passengers, I’m the one treated as suspect. The immigration officer ends up apologizing for having kept me. “I was required to do so, but I can’t tell you why.” A mystery—but after five years of occupation …

Welcomed by C., E., and an envoy from the consulate. C. hasn’t changed. E. either. With the whole circus over at immigration, the goodbyes with L., Mme D., and R. are quick and cold.

Tired. My flu is coming back. I catch my first glimpse of New York on shaky legs. At first sight, a hideous, inhuman city. But I know people can change their mind. Here are the details that strike me: the garbage collectors wear gloves, the traffic is orderly, without the need for officers at the intersections, et cetera, no one ever has any change in this country, and everyone looks as if they’ve just stepped off a low-budget film set. In the evening, crossing Broadway in a taxi, tired and feverish, I’m literally staggered by the circus of bright lights. I’ve come from five years of night, and this intense and violent illumination is the first thing that gives me the impression of being on a new continent (a huge fifteen-meter billboard advertising Camels: a GI, his mouth wide open, lets out huge puffs of real smoke. All of it yellow and red). I go to bed as sick at heart as in body but knowing perfectly well that I’ll have changed my mind in two days.

***

Tuesday. Get up with a fever. Unable to leave the room before noon. When E. arrives, I’m a little better, and I go with him and D., an adman originally from Hungary, for lunch at a French restaurant. I notice that I haven’t noticed the skyscrapers, that they’ve seemed only natural. It’s a question of overall scale. And in any case, you can’t always walk around with your head turned up. A person can keep only so many floors in sight at once. Magnificent food shops. Enough to make all of Europe burst. I admire the women in the streets, the hues of their dresses, and the color of the taxis, which look like insects dressed in their Sunday best, red and yellow and green. As for the tie shops, you have to see them to believe them. So much bad taste hardly seems imaginable. D. assures me Americans don’t like ideas. That’s what they say. I don’t really trust “they.”

At three o’clock, I go see Régine Junier. Admirable spinster who sends me everything she can afford because her father died of tuberculosis when he was twenty-seven, and so … She lives in two rooms, amid a mountain of homemade hats that are exceptionally ugly. But nothing could overshadow the generous and attentive heart that shines through in everything she says. I leave her, devoured by fever and unable to do anything but go back to bed. Too bad for the scheduled meetings. New York’s smell—a perfume of iron and cement—the iron dominates.

In the evening, dinner at Rubens [sic] with L. M. He tells me the very “American tragedy” story of his secretary. Married to a man with whom she’s had two children, she and her mother come to find out the husband’s a homosexual. Separation. The mother, a puritanical Protestant, works on the daughter for months, instilling the idea in her that her children are going to become degenerates. The idiot ends up suffocating one and strangling the other. Declared not guilty by reason of insanity, she’s set free. L. M. tells me his personal theory about Americans. It’s the fifteenth one I’ve heard.

On the corner of East First Street, a small bistro where a screaming mechanical phonograph drowns out all conversation. To get five minutes of silence, you have to put in five cents.

***

Wednesday. A little better this morning. Liebling, from The New Yorker, visits. Charming man. Chiaramonte then Rubé. These last two and I have lunch at a French restaurant. Ch. speaks of America as no one else does, in my opinion. I point out a funeral home to him. He tells me how it works. One of the ways to understand a country is to know how people die there. Here, everything is planned. “You die and we do the rest,” the promotional flyers say. Cemeteries are private property: “Hurry up and secure your spot.” It’s all bought and sold, the transport, the ceremony, et cetera. A dead man is a man who has lived a full life. At Gilson’s place, radio. Then at my place with Vercors, Thimerais, and O’Brien. We discuss tomorrow’s talk. At six o’clock, a drink with Gral at the Saint Regis. I walk back to the hotel along Broadway, lost in the crowd and the enormous illuminated signs. Yes, there’s an American tragedy. It’s what’s oppressed me since I arrived here, though I don’t know what it’s made of yet.

On Bowery Street, a street where the bridal shops stretch for more than five hundred meters. I eat alone in the restaurant from this afternoon. And I come back to write.

The Negro question. We sent a man from Martinique on assignment here. We put him up in Harlem. Vis-à-vis his French colleagues, he saw, for the first time, he wasn’t of the same race. An observation to the contrary: an average American sitting in front of me on the bus stood to give his seat to an older Negro lady.

Impression of overflowing wealth. Inflation is on the way, an American tells me.

***

Thursday. Spent the day dictating my talk. A few jitters in the evening, but I head straight out, and the audience is “glued.” But then, while I’m speaking, someone filches the cashbox, the proceeds of which were to go to French children. At the end of the talk, O’Brien announces what’s happened, and someone in the audience stands up to suggest everyone give the same amount on the way out that they gave on the way in. On the way out, everyone gives much more and the proceeds are considerable. Typical of American generosity. Their hospitality and cordiality are also like this, immediate and without affectation. This is what’s best about them.

***

Their fondness for animals. A multistory pet shop: canaries on the second floor, great apes at the top. A couple of years ago, a man was arrested on Fifth Avenue for driving a giraffe around in his truck. He explained that his giraffe didn’t get enough air out in the suburbs where he kept it and that he’d found this to be a good way to get it some air. In Central Park, a lady brought a gazelle to graze. To the court, she explained that the gazelle was a person. “Yet it doesn’t speak,” the judge said. “Oh, yes, it speaks the language of lovingkindness.” Five-dollar fine. There’s also the three-kilometer tunnel under the Hudson and the impressive bridge to New Jersey.

After the talk, a drink with Schiffrin and Dolorès Vanetti— who speaks the purest slang I’ve ever heard—and with others, too. Madame Schiffrin asks if I was ever an actor.

***

Friday. Knopf. Eleven o’clock. Cream of the crop. Broadcasting. Gilson’s a nice guy. We’ll go see the Bowery together. I have lunch with Rubé and J. de Lannux [sic], who drives us around New York afterward. Beautiful blue sky that reminds me we’re at the same latitude as Lisbon, which is hard to imagine. In tune with the flow of traffic, the gold-lit skyscrapers turn and spin in the blue above our heads. A moment of pleasure.

We go to [Fort] Tryon Park above Harlem, where we tower over the Bronx on one side and the Hudson on the other. Magnolias blooming pretty much everywhere. I try a new type of these ice cream that I enjoy so much. Another moment of pleasure.

At four o’clock Bromley is waiting for me at the hotel. We’re off to New Jersey. Immense landscape of factories, bridges, and railroads. Then, all of a sudden, East Orange, the most postcard-perfect countryside there could be, with thousands of cottages, neat and tidy, set down like toys amid the tall poplars and magnolias. They take me to see the small public library, bright and cheery and used by the whole neighborhood—with its giant children’s reading room. (Finally a country that really takes care of its children.) I look up philosophy in the card catalogue: W. James and that’s it.

At Bromley’s, American hospitality (though his father is from Germany). We work on the translation of Caligula, which he’s finished. He explains to me that I don’t know how to handle my own publicity, that I have a “standing” I should be taking advantage of and that Caligula’s success here will allow me—my children and me—to be free from want. According to his calculations, I’ll earn $1.5 million. I laugh, and he shakes his head. “Oh, you have no sense.” He’s the best of fellows, and he wants us to go to Mexico together. (Nota: he’s an American who doesn’t drink!)

***

Saturday. Régine. I take over the gifts I brought for her, and she sheds tears of happiness.

A drink at Dolorès’s, then Régine takes me to see some American department stores. I think of France. In the evening, dinner with L. M. From the top of the Plaza, I admire the island, covered in its stone monsters. At night, with its millions of illuminated windows and tall black building faces blinking and flashing halfway up to heaven, it makes me think of a gigantic blaze burning itself out, leaving thousands of immense, black carcasses along the horizon, studded with smoldering embers. The charming countess.

***

Sunday. A stroll to Staten Island with Chiaramonte and Abel. On the way back, in Lower Manhattan, immense geological excavations between tightly packed skyscrapers. As we walk past, the feeling of something prehistoric overtakes us. We have dinner in China Town [sic]. For the first time, I’m able to breathe easy, finding real life there, teeming and steady, just as I like it.

***

Monday morning. Stroll with Georgette Pope, who came all the way to my hotel, God knows why. She’s from New Caledonia. “What is your husband’s job?”

“Magician!”

From the top of the Empire State Building, in a glacial wind, we admire New York, its ancient waters and flood of stone.

At lunch, Saint-Ex’s wife—an exuberant person—tells us that back in San Salvador her father had had, alongside seventeen legitimate children, forty bastards, each of whom received a hectare of land.

Evening, interview at the École Libre des Hautes Études. Tired, I go to Broadway with J. S.

Rolley skating [sic] on West Fifty-Second Street. A huge velodrome covered in red velvet and dust. In a rectangular box perched close beneath the ceiling, an old woman plays a most eclectic mix of tunes on a pipe organ. Hundreds of sailors, of girls dressed for the occasion in jumpsuits, pass from arm to arm in an infernal racket of metal wheels and pipe organ. This description could be pushed further.

Then Eddy et Léon [Leon & Eddie’s], a charmless club. To make up for it, J. S. and I have ourselves photographed as Adam and Eve, like one of those photographs you find at fairs, where there are two completely naked cardboard cutouts with openings at the head where you can put your face through.

These diaries are adapted from Travels in the Americas: Notes and Impressions of a New World by Albert Camus, translated by Ryan Bloom and with annotations by Alice Kaplan and Ryan Bloom, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in April. First published in the French as Journaux de voyage by Éditions Gallimard.

Albert Camus (1913–1960) was a French philosopher, writer, and journalist. His books include the novels The Stranger, The Plague, and The Fall, and the philosophical works The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel.Ryan Bloom is an essayist and translator who teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He is the translator of Albert Camus’s Notebooks: 1951–1959.169 Square Feet in Las Vegas

Photograph by Meg Bernhard.

The Las Vegas apartment complex was advertised as a fresh start, a place to reinvent oneself. With only 169 square feet in the so-called “micro-studio,” there was simply no room to bring much of my past life with me. I was not seeking reinvention, but I was looking for cheap rent.

I arrived in late afternoon on a warm fall day. New friends had invited me to go camping in Utah and were soon to depart, so I tossed my few belongings into the studio without taking much stock of the space. I did, however, note what I would come to call “the bathroom situation.” Along the apartment’s eastern wall stood the shower and the toilet, both separated from the rest of the space by only a curtain. The only sink was the kitchen sink. Well, I thought, that pretty much eliminates the possibility of anyone staying the night. I showed up to my friends’ doorstep tired and sweaty, and as we chatted, the last member of our camping caravan emerged from his bedroom, hair damp from a shower. I snuck a glance into his room. His apartment was basically the same size as my entire micro-studio, and contained many more things—paintings from Chile, philodendron cuttings in blue glass vases, and, in the living room, even a large white rug and a recliner.

My tiny apartment, as I named it, was fine for the time being. Utilities were included in the price. I had a desk that doubled as my dining table, and enough cabinets to use for my clothes. There was a kitchenette with a mini fridge and a two-burner stove, where I made, nearly every day, toast and eggs sunny-side up. When I showered, steam filled the room, and the dracaena I’d just bought seemed to like the humidity.

One night, I invited my new friends over for dinner. I owned very few kitchen essentials, so I used a Crockpot Express to steep risotto in wine while I used my only pan to sauté onions. It would take a full day for the smell of caramelized onion to dissipate from the apartment, and, over time, I began to worry that the scents of all my meals had fossilized in my linens. The philodendron man made a comment about a YouTube video he’d watched on micro-studios in New York. Why, we wondered, were there micro-studios in sprawling Las Vegas, where subdivisions and suburbs were more common than even regular-sized apartments? When we left to go eat in the courtyard, our arms full of pots and plates, one of the friends said she’d stay behind. She needed to use the bathroom, but didn’t want anyone else inside at the same time.

Because I lived alone, I normally didn’t close the curtain to use the toilet. I closed the curtain only when I had visitors, which seemed like a performance of modesty, since the toilet was never going to be private. But there were not many visitors. One of my only guests was the philodendron man. The first time he visited by himself, I was nervous. I ended up overcooking the shakshuka I’d planned for dinner, and when he arrived, the place smelled of burn. We drank wine on my bed, and he left. From a friend, I learned he was anxious about the bathroom situation.

When my kitchen felt too small, I’d go over to his house to bake banana bread and roast brussels sprouts, and he and I would sit on the back patio, watching the wind in the overgrown weeds. In the winter, his laundry machine broke, so he would come over to use my facility’s machines, and we’d wait in the tiny apartment while his jeans were drying. He gave me two cacti and placed them on a ledge by the window. “Makes it more homey in here,” he said. Eventually, he started using the toilet, and around that time, he also started sleeping over. His house sometimes felt too big; in the mornings, I’d wake up earlier and make coffee in the kitchen, and he’d join me later. But in my tiny apartment, there was no space for these different routines—no space, really, to be anything but proximate.

My lease ended last May. Now I live with two roommates in a three-bedroom house. We have a couch and a backyard, and I even have my own private bathroom with a door. Sometimes the philodendron man, who is now my partner, tells me he misses the tiny apartment. And I do miss the times when he’d peel away from bed and sit on the toilet, trying to be quiet, or crack the faucet for a cup of water. Despite his attempts at silence, I’d hear everything, and in my dream state I’d think, How nice it is to have someone this close.

Meg Bernhard’s essays and reportage have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. Her book Wine, with Bloomsbury’s object lessons series, comes out in June.

March 13, 2023

The Blk Mind Is a Continuous Mind

Photograph by Thomas Bresson, licensed under CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In his poem “After Avery R. Young,” the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Jericho Brown writes, “The blk mind / Is a continuous mind.” These lines emerge for me as a guiding principle—as a mantra, even—when I consider the work of Black poetry in America, which insists upon the centrality of Black lives to the human story, and offers the terms of memory, music, conscience, and imagination that serve to counteract the many erasures and distortions riddling the prevailing narrative of Black life in this country. Indeed, Black poets help us to consider our past, present, and future not as disparate fragments on a disappearing trail, but rather as a single, emphatic unity: the Was, Is, and Ever-Shall-Be of Black presence and consciousness.

The blk mind is a continuous mind. And language is one site where the continuum of Black life can be perceived, where we can hear ourselves talking to one another across generations, landscapes, and the particularities of circumstance. Indeed, Black poets also hurl their voices across other types of borders to remind us that we are living, sighing, and singing in harmony with others elsewhere and with traditions beyond our own.

I hear a glimmer of this border-spanning continuity in “Dunbar,” Anne Spencer’s 1922 homage to the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar:

Ah, how poets sing and die!

Make one song and Heaven takes it;

Have one heart and Beauty breaks it;

Chatterton, Shelley, Keats and I—

Ah, how poets sing and die!

In the poem, Spencer, speaking as Dunbar, forgoes the Southern Black dialect with which the Black bard is famously associated, for which he was frequently criticized, and to which he sometimes felt uncomfortably obliged. Instead, she aligns him with the idealism, vulnerability, and uncontested authority of England’s Romantic poets. In fact, Spencer’s poem doesn’t bother to argue for Dunbar’s ascension to the Western literary canon; its penultimate line goes so far as to position him firmly within it. In so doing, perhaps the poem seeks not so much to liberate Dunbar from the “one song” or “one heart” of his commitment to Black life, but to remind us that Chatterton, Shelley, and Keats were, similarly, poets of single-minded focus and commitment.

Just as Spencer toggles the frame through which a reader regards Dunbar, the anthology Minor Notes (edited by Joshua Bennett and Jesse McCarthy) invites us to listen anew to voices often occluded by our fixation upon the “headliners” of African American poetry. When I do, I am reminded that the conversation in which Black poets are currently engaged, in the turbulent first quarter of the twenty-first century, began generations and centuries ago when our forebears brought poetic language to the task of pondering and protesting the elusive nature of freedom. George Moses Horton’s apostrophe to the elements in “Praise of Creation” includes these lines addressed to the thunder:

Responsive thunders roll,

Loud acclamations sound,

And show your Maker’s vast control

O’er all the worlds around.

Almost two centuries later, Tyehimba Jess’s poem “What the Wind, Rain, and Thunder Said to Tom” seems to meet Horton’s call with a corresponding response, this time addressed from the elements to mankind:

Become your own full sky. Own

every damn sound that struts through your ears.

Shove notes in your head till they bust out where

your eyes supposed to shine. Cast your lean

brightness across the world and folk will stare

Why is the Black mind a continuous mind? Because the work of freedom is slow. Therefore, our voices must be ever resourceful, traveling forward and backward in time, lending themselves to and beyond our own age in an ongoing collective undertaking.

I like to believe that Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1968 poem “The Second Sermon on the Warpland,” in commanding “Live! / and have your blooming in the noise of the whirlwind,” is seeking in part to tend to and bolster the beleaguered spirit that calls out from Fenton Johnson’s “Song of the Whirlwind”:

Oh, my soul is in the whirlwind,

I am dying in the valley,

Oh, my soul is in the whirlwind

And my bones are in the valley

Angelina Weld Grimké’s early-twenties anti-lynching sonnet, “Trees,” seems also to be directly invoked or reactivated by Brooks’s 1957 poem “The Chicago Defender Sends a Man to Little Rock,” written to mark the backlash, in Little Rock, Arkansas, against the desegregating presence of the Little Rock Nine. Grimké’s poem closes with the following sestet:

Yet here amid the wistful sounds of leaves,

A black-hued gruesome something swings and swings,

Laughter it knew and joy in little things

Till man’s hate ended all. —And so man weaves.

And God, how slow, how very slow weaves He—

Was Christ Himself not nailèd to a tree?

As if to underscore Grimké’s impatience at the slow, slow weaving of both man and God, Brooks’s final lines veer toward the imagery and rhythm of Grimké’s—though perhaps her shortened meter is also an attempt to accelerate the pace of redress:

I saw a bleeding brownish boy. . . .

The lariat lynch-wish I deplored.

The loveliest lynchee was our Lord.

These and other correspondences between poets and across time periods remind me that Black poetry has long occupied itself with the essential work of stewarding a people—and perhaps all people—into the light of freedom. It is a labor of necessity, a struggle under burden. It is also the glorious work of seeding the future.

The blk mind is a continuous mind. Black poets must be awake to their time, attuned to the past, and—in the words of the poet and educator David Wadsworth Cannon, Jr., who was published only posthumously at the behest of family and friends—ever yearning out toward “the pulse of aeons yet to be.”

From the foreword to Minor Notes: Vol. 1, edited by Joshua Bennett and Jesse McCarthy, to be published by Penguin Classics in April.

Tracy K. Smith is the author of the memoir Ordinary Light, a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction, as well as four books of poetry. Eternity, her selected poems, was short-listed for the Forward and T. S. Eliot Prizes. Smith served two terms as the twenty-second poet laureate of the United States, appointed by the Library of Congress.

March 10, 2023

Season of Grapes

Illustration by Na Kim.

As I was going to enter college that fall my parents felt that I should build myself up at a summer camp of some sort. They sent me down to a place in the Ozarks on a beautiful lake. It was called a camp but it was not just for boys. It was for both sexes and all ages. It was a rustic, comfortable place. But I was disappointed to find that most of the young people went to another camp several miles down the lake toward the dam. I spent a great deal of time by myself that summer, which is hardly good for a boy of seventeen.