The Paris Review's Blog, page 62

February 23, 2023

The Review Wins the National Magazine Award for Fiction

Illustration by Na Kim.

We are thrilled to announce that The Paris Review has won the 2023 ASME Award for Fiction. The Review is also nominated in the category of general excellence, with the winner to be announced on March 28. Read the three prizewinning stories—“Trial Run” by Zach Williams, “Winter Term” by Michelle de Kretser, and ”A Good Samaritan” by Addie E. Citchens—unlocked this week in celebration.

The Curtain Is Patterned Gingham

Illustration by Na Kim.

Fictional wall texts, with thanks to the object labels at the Brooklyn Museum.

A fight over pumpernickel bread results in tragedy. Quinto’s use of burgundy paint for the dried blood on the tip of the foreground figure’s machete is related to the shortage of crimson in the nineteenth-century pallet. Quinto died in Brooklyn in 1901.

Gallup Trenton’s wife of forty-two years, Anne Grace Bellington, was his muse and model for works that range from photography to poolside performance. But it was a Memorial Day weekend encounter with his mistress, Pierra de la Fucci, that led to this joyous exploration of romance, foreplay, and the artistic possibilities of plaster of Paris. An artist herself, de la Fucci gifted this sculpture to the Museum after Trenton’s death. The monumental scale of the nude, including its commitment to puckered lips and seductive eye roll, is the embodiment of female power.

The wood used to construct this early Dutch cabinet, including its secret compartment, comes from a genus of tree, Quercus, that is native to 10 percent of New York’s sixty-two counties. The latches are crafted from rose gold.

Little information remains about the origins of these traditional Korean celadon bowls, which have delicate etchings on the inner edges. Scholars suggest that, by the seventeenth century, porcelain had become more popular than the better-known Buncheong stoneware. In the parallel lines across the middle of the cookware, one can see traces of the comblike tool used by the anonymous artisan, the unusual tremors of the artisan’s lines betraying, perhaps, their exhaustion.

In this partially fictionalized scene, Abraham Dinowitz depicts a private dinner at President Washington’s home in Philadelphia. Washington, strikingly, is absent from the dinner itself, instead shown excusing himself to perform ablutions. The core of this work by the noted nineteenth-century caricaturist centers on the pallid faces of the women present, including Martha Washington, Elizabeth Hamilton, Abigail Adams, and the Contessa di Parma, a long-term romantic partner of the Marquis de Lafayette. The contessa is draped in white robes uncharacteristic of the period, a sign of the artist’s playfulness. The curtain in the upper right-hand corner is patterned gingham.

The white-capped mountains and antelope skeleton depicted here mark this classic of Wyoming outdoor painting as an antecedent to the Wind River Range School, whose members achieved fame in San Francisco before descending into madness in the summer of 1863, following floods, hunger, and a latrine-based love triangle involving two of the group’s leading figures. Carter, who died of alcohol poisoning in 1865, paints the wild-haired rancher in the lower left corner at a slightly smaller scale, emphasizing the size of Gannett Peak, the state’s highest point at 13,804 feet. The shade of blue beneath the river is violet aquamarine.

Debuted at the 1833 Salon in Paris, this triumph of animal-kingdom realism was Barye’s first foray into life-size sculpture. The bronze of a lion crushing a snake, an ode to the triumph of the July Revolution of 1830, was created in the Parisian native’s workspace beneath the bistro of the Jardin des Plantes zoo. Barye rented his studio at a high premium so that he could dissect diseased animals and accurately recreate their muscles, armature, positioning, and grace. “He had a predilection for the animal dead since his school years,” his sister said not long before she died in a riding accident in 1872. “For his first sculpture, he inserted marble eyes into the skull of a neighbor’s cow.” Barye’s inability to conform to the era’s human-focused artistic sensibilities often kept him in poverty until his greatest achievement: the launch of a foundry to cast small bronzes in quantity. His facsimiles of foreign animal-fighting scenes became available at moderate prices to the middle class. These casts have been found in the collections of Henry Ford as well as in the municipal buildings of Oxford, Mississippi, and Plattsburgh, New York. Barye’s ingenious industrial breakthrough regarding the mass production of identical pieces laid the groundwork for the expansion of the American railway system and the creation of the Winchester rifle. Today, the Jardin des Plantes zoo does not allow the dissection of any creatures.

In this most carefully composed edition of the artist’s Winter Scenes series, the nineteenth-century Brooklyn waterfront comes to life. The village’s social world is quickly sketched through a collection of figures, each identified in a corresponding key (see right). The inclusion of manual laborers, farmers, and leading members of the legal profession, such as Judge Thos. Willings, displays the national and municipal pride of the artist, himself an immigrant from poverty-stricken rural England who would go on to die destitute. The amateur status of the artist, in a moment when America remained on the periphery of the great European empires, explains the intermittently clumsy groupings of the figures, who do not engage with each other but remain isolated in their own plots of pristine snow. Guy captures the snow’s glare with with careful dabs of aquamarine and sienna. The farmer hauling a load of butter and milk does not notice the bloody dog that has hauled itself to the back of his wagon. The pregnant woman retrieving a drink from the hand pump is dressed in the traditional clothes of mourning, unchaperoned by husband, father, or family relative. In the utmost corner are the two clearest figures. One, a hunched black man, represents the area’s burgeoning African American community (see “The Museum Reconsiders: Part 18”). The figure clutches his buttonless coat in a contrapposto pose as he drags a sled stacked with firewood, which was a precious commodity in New York during all the region’s economic downturns up until the adoption of electricity. The neighboring figure is the body of a catatonic, suffering individual—a self-portrait. The figure’s legs are angled triangularly so as to point to both the Bank of New York and City Hall across the river, in a commentary on the dual power structures of urban life. The figure’s left leg is broken, yet he is laughing. The work came into the Museum’s collection after the death of the artist’s stepdaughter, who had no children.

This figurine of Osiris was executed by Third Intermediate Period artisans. The gnarled finger that extends over chapter six of the Book of the Dead is a noteworthy innovation toward the development of silhouettes.

The aluminum prototype of this futuristic bicycle, known as the Spacelander and manufactured in 1966, was handmade at Grumman Aerospace’s Nassau County headquarters by cousins Anna and Ephraim Lopez. Technical records suggest that Anna, among the first female graduates of the Bronx High School of Science, was responsible for designing the vehicle’s ingenious propulsion system, which stored downhill energy and released it for trips at greater slope. The squirrel tails hanging from each handlebar were sourced from the Great South Bay and signify the earthy discomfort that some Americans, left out of the space race, felt about the vast sums being spent to reach the moon. Ephraim and Anna worked, respectively, in the wiring and chart room outposts of the Apollo lunar landing module project housed at Plant 5 of the Bethpage Grumman complex. Despite the practical benefits of the Spacelander, the Lopezes struggled to mass produce the invention, even before Grumman threatened legal action if they patented their work with any combination of the words lunar, module, landing, space, and fly. The Lopezes’ legal challenges ended with a small settlement. Anna left the company shortly afterward, but Ephraim was promoted to chief engineer of Plant 6, where he remained until Grumman’s merger with Northrop. He died of liver cancer in 1998, ten years before the first acknowledgement from the corporation that the PFAS chemicals used in fire-resistant material on the lunar module had seeped into the area’s sole source aquifer.

This work by an unknown Egyptian artist both models itself on and satirizes Louis Comfort Tiffany’s view of the Alabaster Mosque. It is executed with the same skill and remains an as-accurate portrayal of the exterior of the nineteenth-century construction, though the artist, unlike Tiffany, composed it from life and not from photographs. The practice of capturing Middle Eastern scenes and returning to Europe or America brought wider visions of the world to those then-provincial continents, while also laying the groundwork for the decades of extortion and exoticizing processes that would follow in the artists’ wake. The painting, though unsigned, includes an inscription on the back now understood to be a suicide note for the artist. Modern forensic work to zero in on the identity of this remarkable lost-to-history creator is being conducted by the Museum and local law enforcement through analysis of the bloody half fingerprint in the right-hand corner.

In this startingly intimate portrait, Anna Terrell Etkinson depicts an unnamed aspiring actress soon to make her debut on a post–Civil War New York City stage. Her oil-on-canvas exploration of female ambition is ballasted by an almost terrifyingly dark background that verges towards abstraction. Against such a setting, her sitter appears all the more prepared for large audiences. The rough cotton of the sitter’s collar betrays a modest background, uncommon for the subjects of Lemoyne’s mentor, the noted Boston painter William Morris Hunt. The actress’s pose, as she leans forward with one arm coquettishly balanced on her leg, signifies the changing status of women in the years leading up to Seneca Falls. Yet the actress is out of costume; she is off duty; she holds no stage prop to reassure the viewer that her ambition did anything but curdle. The work was originally held in a private collection under the alternate title “Lover Dies Young.”

This oil painting depicts a haunted nighttime ceremony under the Arc de Triomphe marking the end of World War I hostilities. Often described as lacking in mawkishness and redolent in heavy colors, Tanner’s work invites questions to which there are no answers: Whither death? When shall it come? How should we be remembered? To what end?

The work of Maurice Kish was influenced by the radical political currents of thirties New York City and his own experiences looking for employment. Born in Dvinsk, Russia (now Daugavpils in Latvia), Kish temporarily and unhappily held many roles in the precarious economy of his adopted home, including poet, hansom driver, high school technical drafting teacher, semi-professional boxer, dance instructor, and line worker at multiple Brooklyn factories, where he painted flowers on glass vases. This experience is visible in the underpainting of his most well-known works, where recent digital analysis has discovered the remnants of roses and chrysanthemums on the first layer of his stretched canvases, entirely disappearing beneath the dark monotony of factories, smokestacks, and shuffling and defeated men. Kish, who suffered from severe asthma, was known to bring large canvases to the riverfront facilities where he worked, giving them away to (or pressing them upon) fellow workers who had been let go.

Early logistical support from the British Museum helped this Assyrian relief find its way to Brooklyn, where it has remained through the great turmoils of modernity. In its wake, for the English and then American artistic explorers who sought to replenish their national identities with ancient goods, are at least two crushed legs, one dislocated shoulder, and, for one porter, a lifetime of concussions and jagged conversations that to certain family members seemed a tic akin to battle fatigue. The palace decoration depicts an early warrior king identifiable through his braided beard, hunchback shoulders, and blazing eyes, which course with horror and madness and pity, as if the king knows that even he cannot escape the mortal condition. Indeed he does not, though here his visage remains.

Robert S. Duncanson completed this flawed but alluring depiction of Eden in the years before the Civil War, as an homage to the Thomas Cole work of the same title. The hopeful, paradisiac quality of the composition—trees bent from fruit, beneficent grass, a wide quiet river overlooked by a stately white promenade, half-naked figures dancing—encourages the viewer to consider the possibility of a better country and era for humanity. Known as the American West’s premier African American landscape painter, Duncanson spent his formative years traveling as a journeyman artist, decorating new housing construction in the trompe l’oeil style and enduring days upon days of house painting. As the son of an African American mother and Scottish Canadian father, his oeuvre exudes interstitial realities. Alfred Tennyson praised the American upon meeting him in London in 1853 as “a prophet” and “the last visionary of our species.” Duncanson’s death in 1872 is generally attributed to the mental illness that claimed his final years, which he spent under the belief that he was channeling the spirits and tactile needs of the great deceased masters. “My body,” he wrote in a short journal, “is no longer my own.” Subsequent analysis suggests he suffered from lead poisoning after years of house painting. This unusual oil-on-canvas example of Duncanson’s late-middle career betrays hints of the chemical madness that would overcome him. The sun is less certain than in the Cole original; the only object lit in full is the Grecian temple, which emerges in chilling white from the mauve rock of Midwestern bluffs. The river, in which two women are bathing, is brown with mud. The figures in the foreground grass are obscure enough to be anyone at all. The red dress of the woman staring or genuflecting at a statue is faded tartan. The two figures embracing under the overhanging trees might be wrestling or engaged in the act of love. The image encourages the viewer to consider the truth that anything is possible, including good and evil. There is a man staggering up with great difficulty to the temple.

Mark Chiusano’s story collection Marine Park was a PEN/Hemingway Award honorable mention. His fiction and essays have appeared in McSweeney’s, Guernica, Zyzzyva, and The Atlantic. He’s an editorial writer for Newsday, teaches writing at CUNY City Tech, and is currently working on a book about George Santos.

February 22, 2023

Making of a Poem: Peter Mishler on “My Blockchain”

All images courtesy of Peter Mishler.

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Peter Mishler’s “My Blockchain” appears in our Winter issue, no. 242.

How did you come up with the title for this poem? Were there other titles you thought about?

When “What even is a blockchain/an NFT?” was the subject of conversation everywhere you went, I got interested in the technology’s claim that it creates an “immutable record” of each transaction along the chain of a digital asset’s ownership. I wanted to write a series of personal statements that could not erase what preceded them. Then I noticed this idea was also connected to a certain type of statement—made by a certain type of man—that we’ve seen often, recently: a public apology by someone whose behavior grossly outweighs their supposed contrition. No matter how much they try to distance themselves from themselves, the mea culpa still contains something that can’t be undone: it’s an “immutable record” of all the actions that preceded their apologies, which sound far more like launching an asset than sincerity. So, I thought I would write in the voice of a corrupted consciousness that mirrors the workings of this new bro-corrupted mechanism of capitalism.

I often save my drafts under file names that function as little code words or reminders about a feeling I was having during that day’s writing. “My Blockchain,” though, remained the official title, even as I played with other ways of reminding myself what I was writing.

How did writing this poem start for you?

I knew I wanted to use what ultimately became the final line of the poem—“to hear men sing now I care not”—as an opening or closing. At some point I began to read the line as a turn in the poem. I knew my task would be like the task of a sonnet: to accomplish that turn. I worked on this on and off for a couple of years with various lines, images, and half rhymes coming in and out, though one idea remained consistent: I knew that the penultimate lines would need to complicate the final line’s potential to be read as pedantry. What better way to do that than to imagine it being voiced by a certain kind of man—the type who would sing about himself for seventeen lines and then, in a different register, swiftly renounce that singing on some moral high ground?

An early draft of “My Blockchain.”

What were you listening to/reading/watching while you were writing this?

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been playing music for a record I’m making that converses with a longer poetry manuscript, which includes this poem. I’ve also been writing more, rather than reading. This is very new for me, after many years of compulsive reading. But I’ve decided that at this point in my life I just want to make as much art as possible. So I read the Friday and Sunday paper, and then I get back to my own thing. That’s how I spend my time if I’m not at work or with my wife and children.

Some of the files for drafts of this poem took their name from the Sonic Youth song “Bull in the Heather.” Looking back at these drafts reminded me that I was listening to that song over and over again while writing what became “My Blockchain” because the cadence of that song felt like the right accompaniment for single-line stanzas.

Are there hard and easy poems to write?

The thing that can make writing hard for me is having an expectation that a poem should come together sooner rather than later. To prevent feeling this way, after I’ve published a poem, I compile all the drafts that led to it in a pdf, and on the final page I put the finished poem. These can be very long documents, spanning a number of years, and I look through them to remind myself how long it can take for something to happen. It’s important to remind myself that all writing—whether I perceive it to be productive or unproductive—is always headed in the direction of realizing a finished poem. My main responsibility is to trust that and show up for that, and give myself less room to worry about what poem is going to come, and when.

Playing with rhymes.

When did you know this poem was finished?

Having a poem appear in a magazine makes it a lot easier to stop working on it. I think that’s the moment I finally allow myself to leave it alone and move on to something else, because I know then that it’s communicating something to another person outside of what I’m hearing in it on my own. That doesn’t mean I won’t eventually return to it—but it’s more likely that I’ll return to what I think I might have missed out on in it by writing something new. I find it easier to revise a poem by writing a completely new one where I bring some of the challenges of the old one into play. That way I don’t overwork the old poem or get too far away from its energy, and I get to have that fresh-start feeling.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends?

My wife is a poet, but we spend as little time as possible talking about our work, and we don’t typically share it with each other. We talk a lot about art and music and movies and things, but not about our writing. It’s been really cool at readings when one of us has new work to share and the other gets to hear it as an audience member for the first time, or when one of us gets to read the other’s work first in a magazine. We do, of course, toast to each other’s publications and books, but keeping the act of writing quiet is preferable and even sustaining. It affirms the significance of our individuality and the private creative act. My wife read “My Blockchain” for the first time in the issue when it arrived in the mail, and she very knowingly said, “I see what you’re doing.” That was all I needed to hear. It was a big compliment.

Peter Mishler’s debut poetry collection is Fludde.

February 21, 2023

A Hall of Mirrors

Gary Indiana with Ashley Bickerton, circa 1986. Courtesy of Larry Johnson.

Do Everything in the Dark was the last of three novels I wrote while mostly living in houses in upstate New York or at the Highland Gardens Hotel in Los Angeles. It began as a collaborative book project with a painter, my extraordinary friend Billy Sullivan: I was to write very brief stories to appear beside portraits of his friends and acquaintances, many of whom were also friends of mine. The stories would not be directly about the portrait subjects, but fictions in which some quality or characteristic of a real individual was reflected, stories about characters they might play in a film or a theater piece.

This project was never entirely certain, the prospective publisher having had an opacity comparable to that of Dr. Fu Manchu, and somewhere in the summer of 2001, Billy and I realized our book was never going to happen. By that time I had written most of what appears as the first third of this novel, though, and in this instance I had written past Kafka’s “point of no return” much sooner than I normally did. (I have abandoned many more novels than I’ve ever published, usually realizing after 50 or 60 excited pages that they were heading nowhere I wanted to go.)

One early title I considered was Psychotic Friends Network. At the time, an unusual number of people I knew were experiencing crises in their personal or professional lives, having committed themselves to relationships and careers that, however bright and promising for years, were suddenly not working out. The binary twins, “success” and “failure,” were negligible concerns in what I was writing about, though some of my characters tended to judge themselves and others in those terms; I was far more interested in depicting how things fall apart and reconstitute themselves in the face of disappointment. My overall purpose in writing Do Everything in the Dark was to discover, if I could, what some would call paranormal ways in which a lot of monadic individuals and couples are connected to a vast number of other people, how networks of money, emotions, and wishes overlap across the shrunken geography of a globalized world. I also wanted to write a novel in which the two Greek concepts of time, chronos and kairos, were at work simultaneously, chronos being linear, consecutive, and irreversible, while kairos, “the moment in which things happen,” offers people an opportunity to employ time as a flexible medium—to write books, paint pictures, fall in love, or walk away from unfavorable situations.

When you live alone with characters you’re making up, you are more alone with yourself than you realize. Re-reading this book after twelve years, I see more clearly than I did then that it’s a hall of mirrors. Not everyone in it is me, but I distributed my own insecurities and madness quite liberally among the figures I modeled after people I knew. And the book I thought I was writing from such a dissembling distance from real life situations turns out to be transparently about people whom a great many other people reading it could readily identify. That doesn’t matter. I wasn’t indicting anybody in front of a grand jury. It isn’t a cruel book, or a score-settling one. In certain places, I did defend my side of a few long-recounted, wildly distorted stories people told about me, in a veiled way, but I wasn’t moved by any animus about them; they were just more material when I needed some.

I wouldn’t write a book like this today. A lot of it is prescient, it’s written well, and most of it, I think, is darkly entertaining. But it also has the autumnal bleakness of a cosmic downer, as if a bad acid trip were being experienced by at least twenty people at the same time in different parts of the world. The world is hardly a better place than it was then, but I think it’s possible that I am a better person now than the person who wrote this novel was.

At the time, I had just lost my mother, and my future prospects in the publishing “game” had been yanked out from under me. I was wobbling in and out of severe clinical depressions, which just rolled in clouds through the house at the oddest times, irradiating me with disgust at myself, and revulsion over every decision I’d ever made. I was often sunk so deep in depression that people could smell it on my skin. There was something upsettingly wrong about everything, including the house I’d impulsively bought simply because it was close to the one I’d been renting. The window frames were set wrong, a gangster contractor had installed terrible cheap wainscoting on the walls, claiming it was the only such obtainable these days, rather than the sturdy oak wainscoting found in so many old houses in the area. The original structure had been enlarged and expanded in an insensible manner, the whole layout of the place reflected some long-running cognitive disorder of its previous owners.

My cat, Lily, was terrified of the enormous basement at the bottom of a staircase off the kitchen, a maze of vast low-ceilinged chambers with the atmosphere of a horror movie. Lily never ventured a paw on those stairs.

Months after buying the house, I learned, piece-meal, from people who should have told me what they knew about that house before I signed the mortgage papers, that the sprawling white elephant I’d acquired had functioned in the middle past as a transient home for orphans and abandoned children awaiting adoption into foster care. A few years later, the house became an overflow domestic abuse shelter for women hiding from stalking husbands and boyfriends. There were even indications, in two of the basement areas, that meetings of some disreputable fraternal organization, something along the lines of Storm Front, had been held there for a while. These may also have featured a karaoke night, since besides the crumpled confederate flags and vague neo-Nazi debris scattered in corners, there was also a truncated proscenium stage with a microphone stand and a dead amplifier on it.

My cat had infinitely better sense than I did. She knew right away that house was haunted and that I never should have bought it. In fact the house and the entire area around it, after I had stumbled through the worst confusions of my mother’s death, became obviously, horrifically legible as exactly the kind of “community” I’d left home at 16 to get away from. It even looked like the town I’d grown up in.

I finished the book before I sold the house, but not before 9/11 happened. Writing two-thirds of it after that event probably added even more plangent notes to an already melancholic saga. I don’t think I considered for more than a minute whether to incorporate the disaster itself into the narrative. I decided it would be grotesquely distasteful. Everything I’d written to that point reflected in some manner an unmentioned catastrophe that had either already happened or was about to occur. But this catastrophe existed inside my characters, who were drifting on a historical current more subliminally pitched than the daily news. I didn’t want to exploit something actual that had affected millions in an immediate, dramatic way, or use it as some ghastly metaphor, or wheel it onstage as a spectacular backdrop for stories that were, by their nature, comparatively trivial. It was obvious to me that many people were busy penning exactly those kinds of things within minutes after the planes crashed into the Trade Center—that’s show biz. Even if literature is also show biz, I like to think it’s a reflective person’s show biz. So the book concludes on September 9, 2001, a day that nobody remembers, when the links between various microcosms I invented came full circle.

Gary Indiana is the author of seven novels, a prolific essayist, a visual artist, an actor, a playwright, and the former art critic for the Village Voice. Indiana lives on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. This prologue appears in Do Everything in the Dark, which will be published in April by Semiotext(e). The novel was first published in 2003.

February 17, 2023

Love Songs: “Estoy Aquí”

Shakira. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed Under CCO 2.0

This week, the Review is publishing a series of short reflections on love songs, broadly defined.

Romance and heartbreak are promised before they are experienced. As a child I was filled with a sort of yearning that preceded any actual object of desire. It was a desire for desire itself, one that, like many girls who grew up speaking Spanish in the late nineties and early aughts, I conjured by listening to Shakira’s 1995 album, Pies Descalzos. The first song was my favorite. “Estoy Aquí” begins with a teenage Shakira’s lilting voice over an acoustic guitar: “I know you won’t return,” she sings with quavering melancholy, and then the song explodes into a saccharine tempo unbefitting of a lovelorn person. But how would I have known that? I sang along in my room, imagining that one day I would love someone but also one day I would lose them, and that was even more thrilling. To be alive! And drowning amid “photos and notebooks and things and memories.” I could hardly wait.

In adulthood I have found that intense pleasure and intense grief are startlingly similar experiences—both ecstatic states of being, from the Greek word ekstasis: “entrancement, astonishment, insanity; any displacement or removal from the proper place.” “Estoy Aquí” articulates the specific contours of feeling left behind in a great love’s wake. But, also in adulthood and much to my disappointment, I have found that most affairs end in anticlimax. Twice I have been overcome by the obsessive conjuring of a lost lover; countless times, a budding romance has fizzled out unspectacularly. Infatuation often fails to coalesce into substance. As a child I knew no anthems for the guilt that comes with ghosting or, worse, for the blunt anxiety born of receiving text messages with decreasing frequency. I must admit I feel a little ripped off. “The letters I wrote, I never sent,” sings young Shakira, but what about the pages you leave blank because passion would be unwarranted?

I suppose it is apt that, to borrow from T.S. Eliot, “Estoy Aquí” ends not with a bang but a whimper. The song fades with no resounding note, just a watered down repetition of what has already been stated, a languid dissolution of something that started off so strong.

Ana Karina Zatarain is a writer living in Mexico City. Her debut essay collection, To and From, will be published by Knopf in 2024.

Love Songs: “Slow Show”

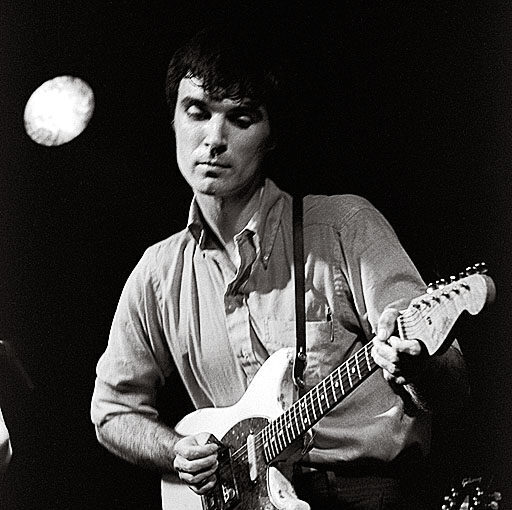

Matt Berninger. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 2.0.

This week, the Review is publishing a series of short reflections on love songs, broadly defined.

In her 1993 memoir Exteriors, drawn from seven years of journal entries, Annie Ernaux describes overhearing a familiar pop song at the supermarket. She is struck by the pleasure she experiences—and by a “feeling of panic that the song will end.” This prompts her to consider the relative emotional effects of books and music. While certain novels have left a “violent impression” on her being, the impact hardly compares to the “intense, almost painful” feeling produced by the song. “A book offers more deliverance, more escape, more fulfillment of desire,” she writes. “In songs one remains locked in desire.” The structure of pop music is inherently erotic; the repetitions of rhythm and melody continually summon and satisfy aching anticipation. Love songs bring this otherwise sublimated longing to the surface: some through grand, theatrical gestures, others by drawing out the dialectic of desire embedded in everyday life—say, the feeling of being alone at a party, sad and self-conscious, desperately missing someone.

This is the premise of “Slow Show,” a somber but rousing midtempo track from The National’s 2007 album Boxer. The narrator spends the verses separated from his lover, surrounded by people but unable to reach them, confined to the claustrophobic quarters of his own mind. Guitars flutter frenetically over foreboding squalls of feedback, while Matt Berninger’s mumbling baritone evokes the narrator’s recursive, dead-end thoughts: “Standing at the punch table, swallowing punch”; “I leaned on the wall, the wall leaned away”; “I better get my shit together, better gather my shit in.” In the choruses, an atmospheric sweetness swells as he briefly spans the distance, if only in his imagination: “I want to hurry home to you,” Berninger croons, “put on a slow, dumb show for you and crack you up / so you can put a blue ribbon on my brain.” His halting syntax smooths out into the simple, fluid choreography of a fantasized intimacy, which disrupts his anxious solitude.

But even the utopic space of the chorus is marred by doubt in its final lines: “God, I’m very, very frightened / I’ll overdo it.” The same fear that strands the narrator alone in the midst of a party gnaws at the edges of his reverie, manifesting now as a terror of spoiling the moment. (In the roiling “Conversation 16,” released a few years after, Berninger intensifies this same dread: “I was afraid I’d eat your brains / ‘cause I’m evil.”) Within each gesture of mutual understanding between lovers there lurks the possibility that the bond might break; the separation that shapes desire shadows every tender encounter.

The song’s extended coda collapses this play of distance and return into a single, paradoxical image of missing what one doesn’t yet know. Over a melancholy piano line, Berninger sings a quatrain adapted from the chorus of a song on the band’s nearly forgotten debut album. “You know I dreamed about you / for twenty-nine years before I saw you / you know I dreamed about you / I missed you for, for twenty-nine years.” It’s a nearly mythic origin story for the mundane set of relations sketched in the rest of the song: in the beginning, there was a longing.

Nathan Goldman is the managing editor of Jewish Currents.

My Ex Recommends

Mark Fenderson, An Idyl of St. Valentine’s Day, 1909. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

My first real lover was dumb, virile, hilarious—I didn’t trust a word he said. Certainly nothing he recommended. This is why, for years, I stayed away from his favorite book, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Until now. I’ve given in, and the epic Western is, predictably, blowing my mind, and, perhaps less predictably, my groin.

I am never sure when carnage might strike—when I might find men whose naked bodies have been “roasted until their heads had charred and the brains bubbled in the skulls and steam sang from their noseholes,” when I’ll come across a “charred coagulate” of bodies or a decapitated man whose severed neck “bubbles gently like a stew.” While reading, my muscles stay flexed. Blood pulses through dilated vessels. Awaiting climax, I am in a state of constant tension. Groin on vibrate. I never uncross my legs. This is reading as grotesque edging.

It doesn’t help that the novel’s landscape is excitingly predatory: “The sun rose … like the head of a great red phallus until it cleared the unseen rim and sat squat and pulsing and malevolent behind them.” McCarthy’s pulsing, penile sun has been making its way into my dreams. So have men—naked, dangerously erect, charging off cliffs, their bodies bursting into constituent parts on the way down, blood running after them in silken crimson ribbons of … But fuck, I can’t do it like him. I wake frustrated.

Adding to the tension is McCarthy’s syntactical cadence. No matter the content, the persistent beat of his language (biblical, oratory, metaphorical, parodic, straightforward) generate a steady thrum—a rhythm that seems to emanate from the throbbing, carnal core of the earth itself. Or perhaps it’s a lover’s incantation—or weapon. You might say that, while reading, McCarthy’s language functions like straps fastened over my body. Hard as I might writhe, those straps are never tightened, they are never loosened—and even though I’ll finish, I will not be released.

—Sophie Madeline Dess, author of “Zalmanovs”

Absalom! Absalom!, William Faulkner

The Annotated Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, ed. Elizabeth D. Samet

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, James M. McPherson

The Civil War, John Keegan

The Civil War (PBS documentary), Ken Burns

CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders

The Killer Angels, Michael Shaara

Shiloh, Shelby Foote

The Trees, Percival Everett

My first husband, when we got together, wanted us to exchange our copies of our favorite books. He was carrying mine around in a bag and immediately lost them. Can’t quite remember what all his were—definitely Sartre, Hesse, The Leopard.

—Lidija Haas, deputy editor

I heard the title song from The Avalanches’ Since I Left You, an electronic album rumored to contain more than 3,500 samples, for the first time during an impromptu date at the library. A bearded new friend and I were exchanging our favorite songs, and he pulled up “Since I Left You” on YouTube. We stood at a computer console nodding our heads to the swirling, symphonic arrangement. I don’t know how I didn’t swoon right there on the spot; I don’t know how the head-nodding and moon-eyed glances didn’t segue into a Lady and the Tramp–style spaghetti kiss over the Avalanches’ spaghetti western strings. I can’t remember if we actually split a pair of earbuds, but we did go on to spend seven years together. As I write this, I’m listening to “Since I Left You” for the first time in a long while. If the song has a hook, I’ve always heard it as: “Since I left you / I found a world so new.” In researching the song’s provenance (an admittedly difficult thing to do given the sheer amount of samples used to make it), I learned that the chorus comes from The Main Attraction’s “Everyday,” which includes the lyric “Since I met you, I found the world so new.” What a difference a word makes. Between “left” and “met” there are thousands of memories and diametrical (last and first) impressions: the silent treatment and the music of early years; hiding resentment behind laptops and sharing a screen; standing apart and swaying in unison. The subtle shift in the article I hear in the lyrics of “Since I Left You” and its source material—“a world” vs “the world”—sums the tension one negotiates between idiosyncrasy and overlapping sensibilities when building, cohabiting, and disassembling a world with someone, and then again in starting over. In its opening seconds, “Stay Another Season,” the song that “Since I Left You” transitions into, seems to sample Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up.” The potential connection between the sentiments expressed in those titles evokes the kind of excommunication, exhumation, and exorcism associated with parsing an ex’s impact.

Nearly fifteen years later, we’ve been separate for as long as we were together, and it’s hard to trace all of his influence. Like the work of a copyright lawyer tasked with identifying the scores of samples that might comprise an Avalanches tune, it’s tough to definitively prove the origins of all the tastes we shared—as in swapping spit, it’s impossible to know where your DNA begins and theirs ends. The associations are loose and incredibly diffuse. I hear him when I play Marlena Shaw’s cover of Carole King’s “So Far Away,” (a song included in a mix CD he made for me) and MF DOOM (a master sampler himself) whom I listened to so much that my ex ended up adoring him. We covered each other in every sense of the word. As music aficionados will tell you, covering, sampling, and interpolating are the ultimate demonstrations of love.

—Niela Orr, contributing editor

Read more meditations on love songs here.

Because I grew up homeschooled, fundamentalist Christian–style, I haven’t seen many movies. My exes almost uniformly attempted to give me a crash course in cinema.

Wings of Desire (1987): Almost caused a break-up. D., whom I’d been seeing for a little over a year, had a transformative experience of cinema seeing it and wanted me to have the same. I promised I’d watch it, then kept delaying—because I was tired after work, or not in the mood. One evening he exploded: “If you don’t want to watch Wings of Desire, just say so! Don’t pretend you do if you don’t!” The ensuing argument—about keeping promises, valuing a partner’s taste, and prioritizing transformative experiences of art—lasted till the early hours. I did watch it, after the relationship ended. It’s the best film I’ve ever seen about angels.

Lift (2001): Marc Isaacs stands in the elevator of an English apartment building, filming the residents as they go up and down. The best exchange: “Are you in love?” Isaacs asks a young man. “Yeah,” he responds, ducking his head and facing away from the camera, toward the doors of the elevator.

Chronicle of a Summer (1961): Recommended by a summer lover in France, all I remember of this film, an early example of cinema verité, is the opening debate about whether it’s possible to behave sincerely when you’re on camera. And flashes of long-legged young women strolling around Saint-Tropez.

Sherman’s March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation (1985): Because S. and I were in the tumultuous period in which the end of an affair becomes visible as a destination, I interpreted this film as a coded message. Three hours of a straight man considering the crimes of history and modernity as well as his own romantic failures certainly didn’t make sustaining love feel possible, and soon it wasn’t.

—Elisa Gonzalez

I was once in love with someone who loved W. G. Sebald. At the time I thought of this person as the great love of my life, and the intervening years have not exactly proven me right or wrong; he was a person I loved very much and we made each other happy and also miserable. I, especially, made him miserable. But I tried very hard to read Sebald, because I wanted to be close to him. I brought The Rings of Saturn on a beach vacation, and I thought it was the most boring book in the world. I even admitted this to him, sort of, in one of our many emails—we were always sending endless emails—and wrote that while I found parts of it gripping, there were other parts that were just “a drag.” We lasted only a few more months, and then we did not speak for years, and during those years I fell in love again, and then out of love, and then back in it, and so on, and I also had occasion to pick up The Rings of Saturn again. I was living in England at the time, and maybe my mood was more attuned to it; maybe I had just grown up a bit. I thought it was brilliant! And sometimes even funny? I read Austerlitz too and I couldn’t believe the existence of a mind like this, one that could synthesize these overlapping images and invented histories and twists and turns, all of it happening in these dense sentences inflected with magic. I wanted, of course, to tell this person about my change of heart, but I didn’t. Part of me wants to say that this might be a metaphor for a relationship that I didn’t recognize as special, or treat as special when I had it, but I’m not sure that’s quite true either—I knew at the time how special it was, and things unfolded as they unfold, and some of that was my fault and some of it wasn’t; we separated, we changed, and my tastes changed, and life goes on.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

Faces at the Bottom of the Well by Derrick Bell, The Trees by Italo Calvino, The White Album by Joan Didion, the Old Testament, and something called Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee were all given or recommended to me by different exes—I don’t have a type!

—Maya Binyam, contributing editor

Love Songs: “You Don’t Know What Love Is”

Nina Simone, 1967. Wikimedia Commons.

This week, the Review is publishing a series of short reflections on love songs, broadly defined.

There was a woman who was always explaining to me the structures of the world, of desire, of experience. Her analysis was brilliant. I have never met somebody so sure of the way things work. Between us, they didn’t. In the end, I learned, form was a problem. Well placed constraints can excite; they can also kill. Either way they tend to leave marks. A studied silence, breezy banter—these are not so convincing if she can take you in at a glance and see where you are still mottled from the pressure of her touch. But it is easy to adopt the position of the wounded lover. If you know what love is, like Nina Simone sings it, then you know that you, too, can leave, must have left, someone with lips that can only taste tears.

Nina Simone was not the first to sing “You Don’t Know What Love Is” and her version is not the most famous. That honor probably belongs to Dinah Washington, with her bright and clear voice, or maybe Chet Baker, about whom I have little to say. Billie Holiday’s take, with her enchanting, off-kilter warble is also probably better known. But Simone’s is something else entirely. Hers was released much later on a collection of rare recordings. It is live, noisy, and the background hum nearly merges with the brushes sliding along the snare drum. That and the crowd’s murmurs lend the track a warmth that all the other versions lack. It speaks, in spite of itself, to love’s inexplicable optimism.

At the very beginning, Simone sings, “You don’t know what love is till you’ve learned the meaning of the blues.” That third word, know, hangs for nearly three seconds. She never loses control of her voice, but she makes the word tremble as does a heart, a hand, a jaw fixing itself in preparation for sentences that cannot be retracted. She performs the standard as a lament sung at the precise moment that mourning’s fog has begun to lift. It is not a warning meant to dissuade young lovers. The blues aren’t miserable; they’re knowing. Simone’s spare rendition comes with the wisdom of experience, of understanding that if love is faith, favor, desire, support, and—when it can be afforded—indulgence and forgiveness, then all of these add up. When it turns, you lose so much: a body to hold yours, eyes that blink too fast in pleasure, a voice that drops too low to even hear it, the rippling sensation that settles somewhere just below the chest. All of the things that accumulate in the miracle of that face besides yours in the morning. It is the loss of such a gift that makes clear what it’s worth.

What makes Simone’s song hopeful rather than bitter is the sly implication that she is not actually singing to a novice. “How could you know how lips hurt,” she asks, “till you’ve kissed and had to pay the cost?” But how many listeners don’t know the price, don’t know “how a lost heart fears the thought of reminiscing”? Love is premeditated grief. That makes it no less enticing. When she sings “lips that taste of tears … lose their taste for kissing,” it sounds to me like she is someone who knows the taste will return. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” is for when love has lost the sheen of the most saccharine romances and yet maintains sufficient force to upend a life. It is for all those loves that come after heartbreak. Perhaps they are not as clean, but they may be stronger.

What is remarkable is that there are no recriminations across the song’s five minutes. It turns out it is not the guilt or moral superiority that is universal, but the hurt. “No, you’ll never know,” she finishes off, “what love is.” Then the audience applauds. Someone in the room stamps their foot or pounds on a table. That feels appropriate to me. Words work for some, but others must reach out for something sturdy. Often one slides between these modes. Bliss makes me bristle. Or at least it imparts a similar sensation: the charge in the air has already shifted. I wish it weren’t so. It is too easy to approach love with hunched shoulders. It is too easy to cast a cool eye on simple odes. It is too easy to resort to name-calling, to look askance at the emotion with all its demanding and needing and call it naive. But I think the truest way to speak of love is from just past its bitter end, when you can see what a kiss costs and know you will pay again.

Blair McClendon is a filmmaker, editor and writer. He lives in New York.

February 16, 2023

Love Songs: “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)”

David Byrne, 1978. Photograph by Michael Markos. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 2.0.

I think the best love songs are simple. They’re simple because love isn’t, simple because we need to dream a little. Complexity, ambiguity, doubt—they can have their place in novels or in the movies. A love song lets you live in the fantasy of the absolute; maybe that’s also why they last only a couple of minutes. And that’s why we carry them with us, play and replay them until they wear out like old clothes. They stand for too much.

I have many songs that mark the time of particular relationships, both their highs and the lows of their dissolution. I’ve played songs on repeat enough to drive people crazy, and I’ve locked myself in my room to listen to late-period Billie Holiday with the lights off. But I have only one renewable love song, which I’ve brought with me through all my relationships: the Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody).” That’s probably because, although it pains me slightly to say this, it began for me as a family romance. When my parents were young and childless and living in Seattle, they saw a sign for the movie Stop Making Sense, Jonathan Demme’s Talking Heads concert film, at a theater near the Pike Place Market. I don’t think my parents were particularly interested in the hip music of the eighties—they just liked the name of the movie. They bought tickets on a whim and went inside.

So the cassette-tape soundtrack of Stop Making Sense was a sonic canvas of my childhood. But it wasn’t until I saw the movie for myself, in high school—watching it with a girl, making feeble couch-based sexual advances—that I was reawakened to the song. It’s unusual for the Heads, who are better known for blending angular, art-school/CBGB cool with African-polyrhythm borrowings. The song is very straightforward. Sentimental, even. But a great love song should be sentimental. Why wouldn’t you try to feel everything you possibly can? The groove begins straightaway—simple drums, the bounce of the bassline, some light synth stabs. A perfect little loop. After a couple of repeats, a bubbling riff kicks in, with a soft, pipelike quality to its pitch-shifting. It reminds me of a calliope, although I’ve never listened to one in real life—it’s children’s music from some other, unlived existence: “Love me till my heart stops / love me till I’m dead.”

That’s the naive part, and isn’t accessing innocence without curdling one of the most difficult things art can do? In the movie, David Byrne is the avatar of unrepressed feelings: gesticulating, shaking, yelping, and squawking. As he says in a promotional interview for the film, wearing his now-famous big gray suit, the body gets bigger so the head can get smaller. In the film’s performance of “Naive Melody,” he performs a pas de deux with a floor lamp, elegant and absurd and melancholy-ordinary. Still, despite the naïveté, there’s something sophisticated about the rest of the title, that “this” must (emphatically) be the place. Where is “this”? It’s anywhere we point to, anywhere we call home. We try it out and see if it works. There’s something beautiful and agonizing about recognizing love as a placeholder, a space we’re always trying to fill. Every day we have to conduct the experiment of calling that love our own. You could be anyone. You could be mine.

David Schurman Wallace is a writer living in New York City. He is an advisory editor at the Review.

Love Songs: “She Will Be Loved”?

High school lockers in Langley, Virginia. Photograph by Elizabeth Murphy. Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CCO 2.0.

Of all the things I didn’t know when I was thirteen, two pained me the most: music and romance. I had no instrument, no boyfriend, no way of predicting, when I dared to accompany the radio in the car, if my note would match that note. Girls who could sing, I observed, had hookups and breakups, and, even better, the whispered hallway dramas that led from one to the other. I made certain inferences. And yet I didn’t see how to, well, join the chorus. A good ear is innate, isn’t it? You can unwrap a hundred Starbursts with your tongue and still know nothing of kissing. So I kept my crushes to myself. I stopped singing in the shower.

But ignorance is good for desire. I don’t doubt the subtle pleasures of connoisseurship, but can it compare to the transcendence of a teenager, luxuriating in her loneliness, who detects in the generic bridge of a Maroon 5 song a message for her alone? To the brief and sacred innocence in which I really, truly took it to heart: “She Will Be Loved”? Hard not to cringe for her, except that I envy her, too.

The lucky truth is that I still don’t know much. Not for lack of trying. My first real boyfriend had thousands of lyrics in his head. He made me playlists, as boyfriends often do. The Velvet Underground, A$AP Rocky, Tom Waits. Yo La Tengo. Later, I dated a drummer and learned (kind of) about jazz and samba, about Milford Graves, who transcribed heartbeats into music notation. An education of sorts, but who, in the end, wants to be schooled by love? These days, I play the Top 40 wherever I go. I turn up the volume. In the seat beside me, the person I love says, I thought you hated this song. And maybe I did! Every now and then, I sing, though not because I’ve conquered any fears or learned any lessons. Mostly, I still just listen.

Clare Sestanovich is the author of the story collection, Objects of Desire.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers