The Paris Review's Blog, page 64

February 9, 2023

Love Songs: “Mississippi”

Bob Dylan. Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CCO 2.0.

This week, the Review is publishing a series of short reflections on love songs, broadly defined.

Someone once accused me of being unrealistic about love’s aftermath. This was in the middle of an interminable argument, one in a long series of interminable arguments. I am not really someone prone to interminable arguments, which probably should have told me something about this person and myself sooner than it did, but at the time I was experiencing a new experience and not every aspect of it was entirely unpleasant. What he said was something like this: “You think there are never any consequences! You think you can go around hurting people, and that everyone you hurt will still want to be in the same room as you, having a drink!” I thought about this for a second. It wasn’t true but it wasn’t not true either. Then I said something stupid, which was, “Do you know the Bob Dylan song ‘Mississippi’?”

Is “Mississippi” a love song? Yes and no. I think it is among the most romantic songs ever written and also among the most ambiguous, which are not disconnected qualities. It is not even clearly about a romantic relationship—some people hear it as a sociopolitical song about the state of America, which isn’t wrong. It might be about a guy who has literally stayed in Mississippi a day too long. Yet it contains, I think, every important kernel of wisdom about love and the loss of it; it hits every note that matters. Is that too much to believe about a single song? “Mississippi”—and I am talking about the Love and Theft version, the heart likes what it likes—is about the love that outlasts love. I think often of the line: “I’ve got nothing but affection for all those who’ve sailed with me.” And I think, Yes, that’s how I feel! This is true!

Of course, it isn’t true. It isn’t any more true for me than it is for anyone who harbors their own bitternesses toward me. I have plenty of things besides affection—wells of pain, streaks of anger, pain and anger about things so long past you would think they would have disappeared rather than calcified. And yet when I hear that line I think about everyone I have ever loved and everyone who has ever loved me—I think of us on a boat together, maybe drinking martinis. But it’s almost like we are ghosts, like the dead children in the final book of The Chronicles of Narnia, because I know this is a wild, impossible fantasy of the past and the present colliding. Still, it’s beautiful and in its own way even comforting.

But then there is the sadder part of this song, which I can’t ignore. There are those heartbreaking lines, “I know you’re sorry / I’m sorry too”—and who isn’t sorry too? Then: “Last night I knew you / tonight I don’t.” Dylan sings those lines in a kind of mournful howl that in certain moods can bring tears to my eyes. After all, more often than not, we become strangers to each other. These lines are truer, probably, than my fantasy of undying affection, though they coexist with it; these things are not mutually exclusive but in fact inextricable. The magic of the song is its ability to contain all of this.

“Mississippi” is a song about longing—overlapping and conflicting kinds of longing. So I suppose what I was asking when I asked this person if they knew the song “Mississippi” was: Do you not understand that I can want everything all at once, even things that contradict each other? Do you not understand that these conflicts and tensions are at the heart of romantic love? And do you not believe, as I do, that love’s shadow extends long past these bitter arguments, and that is what makes it worthwhile and also why it is making us suffer? But I didn’t say those things; instead, I found myself talking about a song. The argument ended in exhaustion, and not too long afterward, we parted ways for good. But what is for good? The past is ticker tape running underneath the present. There are those other perfect lines from the song: “I was thinking about the things that Rosie said / I was dreaming I was sleeping in Rosie’s bed.”

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

February 8, 2023

Three Is a More Interesting Number than Two: A Conversation with Maggie Millner

Maggie Millner. Photograph by Sarah Wagner Miller.

It’s easy to feel happy for a friend who has suddenly, and seemingly irrevocably, fallen in love. It’s just as easy to wonder, privately, if they might, one day, fall out of it. Love stories, like rhymes, are initially generative. Both begin with the promise of infinite possibility: the couple–and the couplet–could go anywhere! But anywhere always winds up being somewhere, and that somewhere is very often a dead end.

Couplets, Maggie Millner’s rhapsodic debut, is officially described as a novel in verse, but the poems that comprise it buck constantly against their generic container. Some are in prose, others are in rhyme and meter, and all are spoken by a young woman straddling two relationships and a shifting sense of self. Affair narratives are all about reversed chronologies: they end where love begins. But when the speaker leaves her long-term boyfriend for a first-time girlfriend, her timelines get all mixed up: she becomes a “conduit / between them: a conversation they conducted / with my mouth.”

Couplets is preoccupied by triangulations. The speaker is intensely jealous of her new girlfriend’s other girlfriend, a novelist who every other weekend also has a “tryst” with a married hedge fund manager and his lover, who is a novelist, too. When he ejaculates into one of the novelists, the other pretends that she is a voyeur, peering in on her competitor, the hedge fund manager’s wife. Meanwhile, the protagonist, a poet, finds that her own love triangle produces shifting meaning. She and her lovers are bound together, but she can’t seem to harness them. “Our own story made no sense / to me and twisted up whenever I tried / writing it.”

At the end of January, Maggie and I spoke over Zoom about the language that attends love and the desires that animate the life of any writer, who will always find herself, no matter the genre, struggling between the impulse to act and the compulsion to self-analyze.

INTERVIEWER

Was there a moment when it suddenly became clear to you that you were writing a book, as opposed to a series of poems?

MILLNER

I hadnt imagined writing a single, book-length narrative poem. When we learn to write poems, we usually learn to write these very small, discrete lyric objects, and so I had always imagined that my first book would be a collection of things that I had foraged from various years of my life. But because I had two year-long fellowships, the ostensible goal of which were to write a book, I was able to be more ambitious. The momentum of this particular poetic form took hold, and I followed it until I had the bulk of a manuscript. Then I realized the prose sections also belonged in it–that the verse needed to be aerated.

INTERVIEWER

What was missing in the couplet form that the prose was able to provide?

MILLNER

There’s a relentlessness to writing in rhyming couples that for the reader can be exhausting and claustrophobic. I was concerned about the lack of formal surprise. But also, life has formal qualities, and a relationship model is a formal question. The book was also very much about putting things in dialectical relation to each other, so I realized that there needed to be some other secondary mode or interlocutor.

INTERVIEWER

The title of the book, Couplets, is a pun, but I also felt it to be a kind of joke, because the couples keep being interrupted by the intrusion of third parties: the speaker’s girlfriend’s girlfriend and the speaker’s ex. I wonder if you find this third necessary in matters of love–if the two depend on it.

MILLNER

Three is a more interesting number than two. There’s a romance to the love triangle. There’s an inherent asymmetry, a more volatile set of relationships. Our desires are most manifest when we’re being pulled in two directions, when there are disparate, orthogonal, or even oppositional forces inside us. Those are the moments when complex self-knowledge happens. The times when you have to prioritize multiple, competing selves lead to personal transformation, I think.

I was thinking of Aristophanes’ idea about the source of romantic love: that people were originally conjoined and then split in half, so we’re doomed to wander the earth until we find our missing counterpart, at which point we become complete. His myth actually makes a provision for gay couples, but it unfolds only within a strictly binary gender system, and only within the premise that there’s a single lasting partner for each of us. If you depart from the idea that the couple is the default, preordained arrangement, suddenly the constructed dimensions of relational structures start to open up. The book’s jacket copy says something about coming out: one woman’s coming-out, coming undone. But I do think those two things are discrete. The consummation of queer desire is a realization that anticipates a later realization, which is that relationships are not inherently meant to be durable.

INTERVIEWER

In Couplets, the only mention of coming out is immediately related to climaxing. Was it important to you to describe this supposedly outward and public-facing process as something very intimate?

MILLNER

The speaker is in part resistant to that climactic, self-actualizing narrative because she is also very reluctant to renounce her previous relationship. If we code her as stepping into some presupposed fate, it turns her previous life into a pretext for this other, truer moment. The cultural incentives to read things that way are both very appealing and very abundant. But the reality is that she still feels real love for her ex, which doesn’t neatly coexist with the role that she is stepping into; the relationship with her ex has an integrity that this book wants to honor. I don’t feel that time is teleological and progressive: that we’re always heading somewhere, but we’re not there yet. I believe that everyone has many lives.

INTERVIEWER

Much of the story of these two couples takes place in a rapidly gentrifying Bedford-Stuyvesant, and the highly specific proper nouns that anchor your speaker to a sense of place and social milieu aren’t easy to square in verse. Eckhaus Latta, Saraghina: I find them to be rather ugly words. Why did you include them?

MILLNER

Through this new relationship, the speaker is stepping into an identity, but she’s also stepping into a social class and milieu that is not entirely comfortable to her, where queerness is the opposite of marginal, and where being a person in an alternative relationship model is actually quite common. She is hyper-attentive to the signifiers that attend this world, which she too finds ugly (and alluring). On the one hand, she longs to be naturalized into it, but on the other, there is also this inevitable friction between the person she knows herself to be within the social contexts that she has occupied, and the world that these proper nouns stand in for. Part of why this isn’t a more triumphant coming out story has to do with the fact that queer life, within the circles she’s in, doesn’t attract public shame. On the contrary, there’s social cachet in stepping into that identity. Which is not to elide the homophobia and queerphobia that continue to dominate most spaces in this country, or the elders and activists who have made communities like this one possible. But for the speaker, there’s something disingenuous about claiming her queerness only as a socially marginal identity.

INTERVIEWER

Toward the very end of the book, the narrator declares that in verse, as opposed to in prose, there are “barely any characters at all.” What do you think about the differences between character as it can be constructed in prose versus poetry?

MILLNER

As contemporary readers of poetry, we often assume that the lyric “I” is the writing self, which does seem to preclude characterization, because that “I” is seen as pointing to a nonfictional human figure. But we’re wrong when we make the assumption that the “I” and the self are coextensive, even in poems that seem totally autobiographical. I want to be taken seriously as a maker of artifice, and I’m interested in inviting my readers away from that assumption, while also maintaining a sense of intimate disclosure, which we typically associate with the lyric poem.

INTERVIEWER

The book is classified as “a novel in verse,” and your speaker is, for a period, intensely jealous of her girlfriend’s girlfriend, who is a novelist. Although she never says so outright, you get the sense that she fears the story this novelist will make of her love for the speaker’s girlfriend will be more compelling than the story the speaker can make in verse. Which makes me wonder, how do you feel about novels and novelists?

MILLNER

There might be more references to novelists in the book than to poets, which is reflective of the speaker’s taste and of a desire to be maximally immersed in experiences of every aesthetic kind. Novels provide that exhaustive immersion. It’s not that poems don’t, but poetry is more condensed and demanding and doesn’t act on attention the way that novelistic prose acts on attention. There’s a passivity and submissiveness that the reader of a novel gets to enjoy. The reader of poetry is invited to focus on granular particulate dimensions language—it’s a less submissive experience, or at least a less passive one.

As a poet, I have an inner conflict around the desire to write a novel while being a poet. I feel pulled in two different directions: I have a strong affinity for narrative, characterization, and durational storytelling, but it’s very hard for me to imagine turning off the poetic apparatus. The speaker is entertaining the possibility of being otherwise, of existing in a slightly different shape. She wonders if her life might be radically different if she could find a form that better reflects what’s going on with her.

INTERVIEWER

The couple form is said to be infinitely transformative, and yet many experience it as a restriction. The same can be said of rhyme and meter. On the one hand, it produces infinite meaning; on the other, it can feel laden with rules. How do you feel about living and working within these two forms?

MILLNER

A foundational belief that undergirds this book is that one way to feel free, to experience agency within the repressive systems that govern our lives, is to historicize and try to understand the material conditions through which they came to be. The idea that to write in free verse is an exercise in unmediated personal expression presupposes so many things about what that form does. The shift away from rhyme and meter is extremely recent relative to literary history; the phrase “free verse” is only a century and a half old. It’s also somewhat oxymoronic; to me, as soon as anything becomes compulsory—as soon as it’s presented as the only available option—it doesn’t make much sense to attach the adjective free to it. Contemporary poets are generally expected, with the consensus of the commercial and academic institutions, to write in ways that sound more like speech than like oldfangled verse forms. So the idea that writing in an inherited form is a deviation from the default is, ironically, a basically presentist idea. Still, if radical forms are those that stage a departure from the status quo, we live in a time when using rhyme and meter can actually qualify. I would argue that they can even take on a new political charge when used by people historically excluded from the institutions that propagated them.

I feel similarly vexed about relationship structures. I do feel there is something amazing and irreplicable about the experience of being in a couple. And I don’t think that experience is only a cultural production—there’s something genuinely special that can happen between two individuals. Moments of intimacy with one other person have been the most transformative, spiritual moments of my life. The speaker of Couplets is magnetized toward those experiences. They’re real, they’re important, and they’re beautiful—they’re what it’s all about. But through those experiences, she finds herself unwittingly signed up for a certain kind of partnership—caught in a default she didn’t necessarily choose.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel as if the couple is a flawed form that we have to reinvent, to the extent that reinvention is possible? Or do you believe that the couple is an ideal form that is tarnished by lived reality?

MILLNER

I think the issue is not with the structure of the couple, but with the telos of any relationship being eternity–the idea that the couple is a form you only step into and never out of. There is something exalted about the experience that two individuals can have with each other. Suddenly, you’re not really an individual, which is the profundity that you experience in the presence of an other. I feel very attached to that. But this book is an experiment in thinking through the question, What if staying together wasn’t the tacit objective of every relationship? In Poetic Closure, Barbara Herrnstein Smith writes that the couplet is a unit that enacts closure. Every two lines, there’s resolution. And so there’s a propulsive momentum to the form, but it also pretends to arrive at closure over, and over, and over again. There’s an assumption that the couple is a closed container, but the couplet unravels that assumption through repetition.

INTERVIEWER

I was struck by how resistant your speaker is to the endings that might otherwise be imposed upon her; she leaves her boyfriend but feels herself conducting his mannerisms in her relationship with her girlfriend, so that the two meet in her. Why were you drawn to that choreography, which seems impossible for a book about couples, written in couplets?

MILLNER

On the one hand, we are all familiar with the story of falling in love–we all know how it can go. And at the same time, we don’t, as a culture, have many urtexts about voluntary breakups, because divorce only stopped being taboo, like, yesterday. The idea that a marriage is composed of two subjects who are equally entitled to an experience of self-actualization is not very old—even younger than free verse! If we look at our great foundational texts, especially within the Western canon, relationships end nonconsensually, either by death or by some other nonmutual event.

There’s a reason that literature is still being written about the fundamental question of how to know when a relationship is over, even if you still have an attachment to that person. We don’t have cultural scripts for those questions, and the way they are legislated is still retrograde and dependent on conservative notions of the sanctity of the nuclear family. The speaker of my book is very much reckoning with the residues of historical expectations of what women owe men. There’s a great temptation on the part of women in hetero partnerships to feel an outsized sense of responsibility for their demise.

Maya Binyam is a contributing editor at The Review.

February 7, 2023

The Smoker

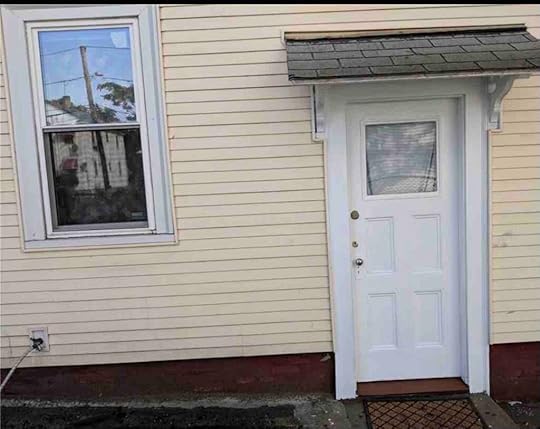

Photograph by Ottessa Moshfegh.

This one time, my dad bought me a house in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a two-story fake Colonial with yellow aluminum siding on Hawkins Street. We bought it from the bank for $55,000; it was one of many properties under foreclosure in the city in 2009. Dad and I had spent a few days driving around and looking at these houses. In one driveway, I found a dirty playing card depicting the biggest penis I could ever imagine—I still have it. In one basement, the realtor had to disclose, the former owner had tied his girlfriend’s lover to a chair, tortured him, and then shot him in the head.

The man who had lived in my house on Hawkins Street had owed more on the house than it was worth. It was in an undesirable part of town, or so I was told, but I loved the neighborhood. The houses were small. There was a permanent lemon icee stand a block away. I was about twenty steps away from a bodega that functioned as the neighborhood grocery store. My next door neighbor was an elderly lady from Portugal who spoke almost no English and yet complained to me about all the dogshit in my backyard while bragging about the tomatoes in her garden, which looked exactly like her breasts beneath her housedress, heavy and sliding. We were separated by a chainlink fence.

The layout of the house was nothing special. When you walked through the front door, you could go up the staircase on the left. Or you could walk straight down the hall, past the small living room, to the kitchen, and from the kitchen you could take a u-turn and step down to the side-door to the driveway, or continue on down to the basement. I had never had a house of my own. When we signed the papers, I felt myself moving into a new phase of my life, a rite of passage with my father in the chair next to me. It was a beautiful and slightly terrifying experience I know I was very lucky to have, and I loved the house, I loved the light and the intimacy of the rooms, and I loved writing in that house. I wrote McGlue in that house. But more than anything, I loved that house because Dad and I renovated it together. Every day for months, he drove down from Massachusetts with his tools. We’d work all morning sanding and painting, breaking down walls, laying tile, whatever, then go have foot-long Subway sandwiches at the Walmart, hit the Home Depot, and go back to work until it was dark and the rush hour traffic had died down. This was the most time I had ever spent with Dad. It was fun and emotional and felt like the fulfillment of a childhood fantasy.

The biggest issue that needed to be addressed—the thing that made the house unlivable—was the nicotine. I don’t mean that the place smelled of cigarette smoke or old cigarettes or ash or the butts stubbed out on the greasy parquet floor. I mean that there was nicotine syrup soaked into the walls. Have you ever smoked a cigarette in a small room in Providence in the summer, in the still of the night? Cigarette smoke is distilled in the lungs, and upon exhalation, the nicotine adheres to the moisture in the environment, the droplets land, the nicotine is absorbed, and the poison never leaves. The interior of the house had a layer of nicotine varnish that made everything sepia and gross. You cannot scrub this stuff off anything except, maybe, stainless steel. So Dad and I had to rip out all the walls.

I can’t really remember what the kitchen was like when we got the house, although I’m sure Dad took a picture. I just remember using a sledgehammer. I had been an on-and-off smoker for many years—something I tried (and probably failed) to hide from my parents. (I finally quit last year thanks to Chantix and the grace of God.) I mention this to stress that I was used to the smell of smoke. But this was something different. It was, literally, the smell of carcinogens. And yet the demolition was kind of sad. When I was breaking up the walls in the kitchen, I found horsehair in the plaster, and a sloppily potato-printed wallpaper I wished I could keep.

Upstairs was a slightly different story. The previous owner had painted the walls orange, laid huge white tiles down the hallway, and installed some kitchen cabinets in a windowless area by the bathroom. An old fridge stood awkwardly, wedged as far is it could get under the sloped roof ceiling. It appeared to be a half-renovated rental unit. It wasn’t a bad idea, and I did use that fridge while the real kitchen downstairs was being gutted and renewed. I mention this because it isIt was part of the interrupted life of the house. The previous owner wanted to turn the upstairs into an independent apartment. He had obviously failed to keep up with the mortgage. Maybe if he’d finished sooner, and rented out the upstairs, everything would have been okay.

One day, when Dad and I were at work in the kitchen, a guy pulled into the driveway, walked in through the side-door, took one look at the place, and lit a cigarette. He didn’t introduce himself or say hello. We knew exactly who he was. I tried to talk to him. He kind of waved me away, and looked at the crumbled drywall on the floor. He didn’t come any further into the house. Dad and I put down our tools and stood, a little penitent, while he smoked. Finally, he threw the cigarette on the floor, crushed it under his sandal, opened his mouth to speak, but began to cry instead. It was horrible. It was heartbreaking. It was so bad. I looked at my dad. He made no expression. There was nothing to say or to do. We just stood there, respectfully, gazing downward as the man cried and rubbed his face and pulled another cigarette out and lit it. Finally, when he was done crying, he turned to us and said, “I used to live here.” He kicked at some broken plaster on the floor. “I’m so sorry,” I said. He waved his hand as though to say, “It doesn’t matter. Nothing matters.” He took one more long, hard drag, coughed for about a minute straight, and then went out the side-door and drove away.

Ottessa Moshfegh is a novelist and screenwriter. Her latest novel, Lapvona, is out now.

February 6, 2023

Quiet: A Syllabus

For most of my life, I took quiet to mean a kind of shortcoming. I had heard it used too many times as a description of how others saw me. But then I realized that in the work of writers I love deeply are many kinds of quiets—those of catharsis, of subversiveness, of gaping loss or simple, sensual joy. I came to think of quiet not as an adjective or verb or noun, but as a kind of technique.

The books I chose for the syllabus below expand how we think about black expression, intimacy, interiority, and agency; about black quietude. I began with the work of Kevin Quashie, whose voice, like a tuning fork, set a tone for my reading of other books. For the nonfiction books on this list, I looked for thinkers who are deeply attentive to the everyday. For fiction and poetry, I selected writers who allow us to glimpse more clearly our own selfhoods via the unknowability of others. In all cases, these are books that are richer for asking us to listen more deeply. We might return from each one dazzled, dazed even, but always with renewed, sharpened perception.

Kevin Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture

Elizabeth Alexander, The Black Interior

Toni Morrison, Sula

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval

Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha

Natasha Brown, Assembly

Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes

Margo Jefferson, Constructing a Nervous System

Robin Coste Lewis, To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness

Lucille Clifton, Generations

Dionne Brand, The Blue Clerk

Grace Nichols, Lazy Thoughts of a Lazy Woman and Other Poems

M. NourbeSe Philip, She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks

Kathleen Collins, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

Victoria Adukwei Bulley is a poet, a writer, and an artist. She is an alumna of the Barbican Young Poets and recipient of an Eric Gregory Award. Quiet, her debut poetry collection, is a finalist for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Rathbones/Folio award. It will be published by Alfred A. Knopf this month.

February 3, 2023

On Hegel, Nadine Gordimer, and Kyle Abraham

Gianna Theodore in Kyle Abraham’s Our Indigo: If We Were a Love Song.

Over the past year I have read and reread Angelica Nuzzo’s book Approaching Hegel’s Logic, Obliquely, in which Nuzzo guides the reader through Hegel’s Science of Logic. Nuzzo presents the question of how we are to think about history as it unfolds amid chaos and relentless crises. How, in other words, are we to find a means to think outside the incessant whirr of our times? The answer she provides is one I find wholly satisfactory: it is through the work of Hegel that we are best able to think about and think through the current state of the world, precisely because his work is itself an exploration of thinking—particularly Science of Logic, as Nuzzo eloquently explains:

Hegel’s dialectic-speculative logic is the only one that aims at—and succeeds in—accounting for the dynamic of real processes: natural, psychological but also social, political, and historical processes. It is a logic that attempts to think of change and transformation in their dynamic flux not by fixating movement in abstract static descriptions but by performing movement itself.

By tracking the movement of the mind, a movement that is incessant and fluid, we are best equipped to study the crises of our time as they occur. In particular, we are best able to examine and analyze the structure of capitalism itself, a structure which is formed by exchange value and is thus a system of infinite repetition and reproduction. A system of infinite plasticity—appropriating everything it comes in contact with. A system, in other words, akin to that of the mind. Hegel does not merely explain how the mind works but enacts its very movement. He places us in the center of its whirr.

—Cynthia Cruz, author of “ Charity Balls ”

For the past few months, I’ve been reading novels about white women settlers in colonial and post-independent Africa. Many of the protagonists I’ve encountered are coming of age; their journeys are heroes’ journeys, culminating in a coupling that enshrines, perhaps paradoxically, their so-called independence, a process that is almost always set against an independence movement, whether a successful or an ongoing one. In Nadine Gordimer’s The Late Bourgeois World, published in 1966 and set during apartheid, Liz Van Den Sandt is already divorced. Her ex-husband, a militant communist who has disavowed his Boer upbringing, has just drowned himself. She feels no sympathy for him, although she is convinced that his tactics (acting as a rogue bomber, and then as an informant once he was caught) were righteous: “he went after the right things, even if perhaps it was the wrong way,” she tells their son, who is completely undisturbed by the news of his father’s death. “If he failed, well, that’s better than making no attempt.” But Liz herself seems without conviction altogether: having left political life, she has now taken as her part-time lover a man with good taste and no political conscience. Nevertheless, she feels herself distinct from the consumer-driven white women around her, “the good citizens who never had any doubt about where their allegiance lay.” When she is asked by a former black political ally (another sometimes lover) to take a potentially risky action, she can see no reason not to. And yet she hesitates and finds excuses, seeing in her ally’s pleas only what she imagines he projects onto her. I don’t know if I liked or disliked the book. Some parts I found pleasurable, and other parts painful and intolerable. But as a data point, I found its cynical literalism intriguing. “A sympathetic white woman hasn’t got anything to offer,” she muses, “except the footing she keeps in the good old white Reserve of banks and privileges.” In exchange, all she can hope for is the possibility of sex, “this time or next time.”

—Maya Binyam, contributing editor

Recently, I’ve been obsessed with a video recording of a performance I saw last April at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston: three works by the choreographer Kyle Abraham, among them the haunting Our Indigo: If We Were a Love Song. Abraham has become well-known for large-scale collaborations with Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, and Sufjan Stevens. But Love Song is understated: it’s a curation of solos, duos, and trios set to Nina Simone, each of them a private moment or choreographic journal entry. The dance makes me want to move and groove, while also rooting me to the spot, so arresting is its beauty. In a solo set to Simone’s “Little Girl Blue,” Gianna Theodore coils her way across the space in a sequence of delicate and acrobatic floor work. In a kind of silent break dance, she lays her whole body weight into the ground only to spring back up in time with the music. “Why won’t somebody send a tender blue boy,” Simone sings, as Theodore moves effortlessly between crouching and standing, “to cheer up little girl blue.” In the video, Theodore appears against a shocking yellow-and-white tile wall wearing a simple navy dress. Though the close-up shots elide some of her larger movements, they also draw me close to her private sensations and memories. Watching Theodore’s blue dress trail on the ground, her hands checking the hem as she kneels, I encounter my own sense memories: the silhouette of my grandmother, dancer-thin behind a cloud of cigarette smoke, humming along to Nina Simone. To see Abraham’s work performed by his company, A.I.M., is a particular treat, so fluent the dancers are in his physical language. You can catch them performing Our Indigo: If We Were a Love Song in New York at the Joyce Theater April 4–9.

—Elinor Hitt, reader

February 2, 2023

Space for Misunderstanding: A Conversation between A. M. Homes and Yiyun Li

Photograph of A. M. Homes by Marion Ettlinger. Photograph of Yiyun Li by Basso Cannarsa/Agence Opale.

A few times a year, the writers Yiyun Li and A. M. Homes sit down to lunch. As friends, they often find themselves talking about almost anything but writing. Often, though, as they ask each other questions, something interesting and unexpected happens: “The thin thread of a story might be unearthed,” Homes recently told us, “or the detail of a recent experience, or a gnawing question one finds unanswerable. Somewhere between the menu, the meal and the coffee, maybe the story begins to form.”

Last year, Li and Homes both published new novels. In Li’s The Book Of Goose, she tells the story of a complex friendship between Agnes and Fabienne, farm girls, who each have been in some way neglected by their families. Homes’s latest book, The Unfolding, is a political satire that explores the fault lines of American politics within a family.

At the end of the year, the two friends sat down for one of their lunches—and what follows is a bit of what they talked about.

HOMES

Funnily enough, as colleagues and friends, one of the things that we never talk about is writing.

LI

Once in a while I will tell you a story or say something has happened, and you’ll say, “Write that into a story.” That has happened three times. Particularly with the story “All Will Be Well,” as I explained in an interview with The New Yorker: “Sometimes it needs a nudge from another person. I was talking with my friend A. M. Homes one day, and I told her about this practice in California, where we were asked to send care packages to our children’s preschool with a letter, in case of a catastrophic earthquake. She said, ‘You have to write a story about that.’ It had not occurred to me until then, and it turned out that there was a place for the care package in a story.” I think you have a specific talent for saying, “Well, that’s an idea.” There’s an expansiveness to the way you look at the world. Do you look through a telescope or a microscope? Where does it come from?

HOMES

I would say my way of looking comes from growing up as an outsider in my own family—a person adopted into a family. I felt other and different and experienced the world as an observer. There’s a space between me and other people that would otherwise perhaps not exist.

LI

Do you still feel that way?

HOMES

I do. It’s a strange position that has also given me enormous freedom to inhabit others and create characters. I don’t feel wedded to any particular identity because I don’t feel I have an identity.

LI

I come from a different kind of family, where I often wished that I were adopted. When someone’s scrutinizing you all the time, your instinct can be not to look at them, not to think about them. Because I’m sheltering myself from all these things in my own life, I can create an alternative universe where my perspective is.

HOMES

It’s like you’re on the outside, and a shade has gone down that says “Closed for the afternoon” and no one can see that you’re inside, looking off in a different direction.

LI

Yes, and for you, it’s like you’re outside the house and the shade comes down, and you’re thinking, “What’s going on inside the house?”

HOMES

Exactly. And wondering: do I even have a key to the house?

LI

So, where are you looking at this moment?

HOMES

For better or worse, I’m a very American writer, so I’m looking at the way we consume things. I’m increasingly interested in economics and how a person’s economic life affects their narrative and trajectory. Where and how a person lives, whether they have money or have access to health care, all these things change the course of their life profoundly. I always feel that, in fiction, and certainly when we discuss fiction, we don’t talk about those things enough, but I’m fascinated by their implications.

LI

I always say that every character has to have a job. Many students create characters who don’t have jobs. They don’t work.

Certainly the reason I’m so curious about the concept of the quintessential American writer is because I am not one, although my coming of age as a writer happened in America. So I’m curious about how you define an American writer.

HOMES

That’s a good question—how does one define an American writer? To be honest, I think that raises another question that until recently I’ve been loath to discuss. That questions is, How does one define an American female writer versus an American male writer? The gender gap with regard to material and expectation and even who reads the books feels larger to me in America than in other countries. In the U.S., men write the Great American Novels—the books about the scale and scope of the American social, political, economic experience—and women are supposed to write the smaller-scale, intimate, domestic stories. In other countries things are not so divided. There is not Women’s Literature, or Chick Lit, and then Men’s Literature. This bothers me a lot, and I would say that my most recent book, The Unfolding, is an attempt to do both—to write both the large-scale, state-of-the-nation novel and also unpack the small-scale, intimate life of a family. But almost as soon as the book came out, a bookseller asked me, “Who is this book for?” and I was caught off guard. I didn’t know what she meant. Was she asking is it for men or women? Was she asking is it for people who agree with my point of view? I don’t know—when I am writing I never think about who this book is for—beyond the hope that my fiction is both entertaining, funny, and provokes thought, robust conversation, and debate about the issues of our time. Does that make any sense or say anything about the American novel?

LI

One thing I can relate to as an American writer is clarity. I was in a cab in Beijing recently, and the cab driver asked me what I did for a living. I said, “I’m a writer.” This cab driver, who had apparently read many books translated from English, and especially American writers, said, “American writers are very straightforward. In China, we consider writing as making circles. You do all these hide-and-seek games. You never say what you want to say.” He said, “American writers, they say what they want to say.”

HOMES

That’s a super-interesting idea—depending on what country someone is from, one has more or less freedom to say directly what they want to say or to code their writing in some way so that someone can extrapolate another meaning from it.

I think there is accuracy to the idea that there is a bluntness to American writing. It aims for an immediate connection with the reader. And it’s almost as though sometimes there’s not a lot of room to build the relationship, because the attention span is so short that either you connect immediately or it’s over. It’s almost like, Swipe right. You escaped that in The Book of Goose, which I think of as originating from a more European model.

LI

The world of my novel is entirely rural. It’s set in the French countryside. My characters are French girls. But they will never place their own lives in a historical setting. They will never say, We are two French girls living in the countryside in poverty post–World War II under American occupation. All these historical terms describing their existence do not matter to them. I felt liberated writing about them because I did not have to worry about all these things that critics would say about rural France, post–World War II, the American occupation. No, this is a world made up by two girls, entirely made up by two girls. I feel that I got a little, like, a shortcut because my characters live in their own world in a way. Would you say that you are the opposite?

HOMES

Yes and no. It’s beautiful the way you described the characters in The Book of Goose as living in the world of their imagination and their physical existence and their environment. It’s a world from inside out—and actually I always start from that point, too, the interior of the character—although in The Unfolding in particular there is a lot of social, cultural, and political framing and large amounts of history and fact. So it is absolutely both in the mind’s eye of the characters, but as they are participating in the known world in a very obvious sense.

Another thing we share: We both live in our imaginations and we pull in threads from our worlds and our experiences, but they are not the dominant theme. We are not writing about ourselves.

LI

I don’t find myself that interesting.

HOMES

I don’t find myself that interesting either. Like you, I have written about myself at times and about experiences that I’ve had, but fundamentally, it’s not the thing I enjoy most.

LI

Do you think readers like to go beyond themselves?

HOMES

I’m not sure anymore. When I was growing up, all I was looking for was a way out—a way into another world. So I read biographies. I thought, “Just show me how to be a person. Show me how to live a life.”

I think that, as things have become more fractured, people seem to read to confirm their ideas about themselves and their identities. They’re looking for a mirror. We also are in a moment when misunderstanding is not tolerated. But misunderstanding is fundamental to growth because you cannot assume everyone will understand everything, nor can you assume that they will agree. So you have to have a zone where you can navigate that. I’ve always found that reading and writing books helped me to do that.

LI

Where is the zone now? Where is that space? How do we make that space? I did an event with Garth Greenwell, and he mentioned—and it’s true—that people always say my work is too bleak. I said, “The bleakest thing is when life is bleak and you pretend it’s very rosy.” I’m in the William Trevor camp of writers. John Banville described Trevor and said, “William Trevor arrives in a beautiful town, and he looks around and says, ‘How beautiful is this town? Let me write and find out what’s wrong with it.’” My belief is that there’s something innately unsettling and troubling underneath. I want to write to find that layer rather than cover that layer up.

HOMES

I’m curious about your relationship to secrets. Are secrets helpful? Do you think of yourself as secretive?

LI

I want to make a distinction between secretive and private. John McGahern famously said that Irish people don’t have privacy, only secrets. It’s a lie that you live your entire life inside the church, inside society.

Even with no secrets, you can always hold something in your heart. So I feel that at this moment I’m not secretive but I have my privacy. How about you? I think you are more outgoing, more out there.

HOMES

I don’t have secrets anymore. I think it comes from the fact that I’m actually painfully shy. When I was younger, people sometimes misread that as my being formal or off-putting, and so I worked to show that I’m not scary. But now it’s like I’m naked, I have no covering, no shell, which is another problem. I definitely don’t have any secrets. I also don’t feel like I have a lot of privacy.

LI

What about your characters? All characters have secrets, but they don’t seem to have privacy because of the way we look at them. How do you think about that?

HOMES

I would say my characters in my most recent book have so many secrets that I don’t even begin to know how deep they go, and they are also pretty private. In the book before this one, I was writing this character, Harold Silver, who’s a Nixon scholar, and I found him very difficult. I kept asking myself, “Why is it so hard to write this?” Slowly, I came to understand that I didn’t know Harold Silver because Harold does not know himself. And only as Harold came to know himself did the book become easier to write.

I have a craft question for you. When I read your work, it feels to me so well-crafted and so fine-tuned, and each line is really perfect and beautiful. I wonder, do they come out that way? Or what is your revision process like?

LI

No, of course nothing comes out perfect, right? With this new book, The Book of Goose, the first draft was one hundred fifty pages longer than the final. Secondly, there was an unnecessary frame, a bit like the one in Lolita. I was very attached to that frame, but everybody, all my early readers, indicated that it was not going to work.

HOMES

But you needed it to write it.

LI

I think that frame was for my psychological comfort. I argued, I defended the frame, and eventually my editor said, “I think you want the book to be a different one than the book is meant to be.” And when she said that, I thought, “Oh, that makes sense.” So I cut away the frame. I rewrote the second half. How many drafts did you do of your recent book?

HOMES

What’s interesting is that each book defines its own terms. With The Unfolding, the complexity was in figuring out the weave of the stories. I didn’t want each person’s story to repeat itself or each character to have to expound upon the same experience. So it was a question of how to keep it moving forward without accounting for each character in every moment.

Grace Paley used to say to me that the bummer about being a writer is that you’re never promoted to senior vice president of writing. Every time you are thrown back to the beginning. You might acquire some skills for the management of problems, but each book is so different, and you have a different agenda because you’re not trying to just repeat yourself. So you have to discover what the terms are of that book and how it will operate and the ways in which it has weaknesses.

LI

Totally. That’s an argument I constantly have with how books are read—they’re read as products. Books are not products. A book cannot be perfect. Nothing is proportional. Nothing is perfect. Some of Mavis Gallant’s books, for instance, are just so good and terrible at the same time, and all I can say is that she gave birth to a baby that looks different from all the babies in the world.

A. M. Homes is the author of thirteen books of fiction and nonfiction, including The Unfolding; May We Be Forgiven, which won the Women’s Prize for Fiction; and the bestselling memoir The Mistress’s Daughter. She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and The Guggenheim Foundation, and is active on the boards of numerous arts organizations. She teaches in the creative writing program at Princeton University.

Yiyun Li is the author of eleven books of fiction and nonfiction, including the novels The Book of Goose and Where Reasons End. She is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a Windham-Campbell Prize, a PEN/Jean Stein Award, and a PEN/Malamud Award, among other honors. She teaches at Princeton University.

February 1, 2023

Postcard from Hudson

Belted Galloway. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 2.0.

The other day we went to Albany so I could return all eight items I had bought online from Athleta. The store was in a giant mall that smelled tragically of Cinnabons. The Cinnabons reminded me of the TV series Better Call Saul, which is set in part in a Cinnabon shop, and the way Saul Goodman was unable to resist pulling a con. He missed his old life. Jail was preferable to feeling unknown to himself.

The clothes in the store were made of fabrics that were “what is this?” and “no.” And there were mirrors, unlike in our house. Richard said, “Let’s go to the Banana.” He wanted a cashmere sweater. There were two he looked great in, and it made me so happy for someone to look good in clothes I said, “Buy both.” He said, “I don’t deserve them.” I said, “No one deserves anything. You are beautiful. Beauty is its own whatever.” One of the sweaters had a soft hoodie thing, and Richard liked walking around in the house in it. The hood came down a little low. I said, “You’re getting a seven dwarfs thing happening with the hood.” He pulled it back a little, and it was perfect.

The next day on our walk, he wore the hoodie over a cap covering his ears. When we recited three things in the moment we loved, he said, “I’m glad we’re walking, although I’m against it.” I said, “Why are you against it?” He said, “It’s too cold.” It was during the Arctic cyclone, and I was wearing my down coat from the eighties. The shoulder pads are out to Mars, and Richard said, “Everyone on Warren Street thinks you’ve been released from an alien abduction after thirty years. They are wondering why you were released.” I said, “Why was I released?” He said, “They couldn’t get anything useful from you about earthlings. It was a total waste of their time.”

I bought a giant wheel of focaccia with salt and olives from a bakery. The grease was soaking through the bag when I got outside. I tore off a hunk. Richard said, “Are you going to eat all that?” I said, “It tastes like a crispy pretzel from Central Park,” and I could see I was missing my old life. The way we live, there are cows outside our windows that belong to Abby Rockefeller. Abby Rockefeller has built a dairy farm down the road where a piece of cheese is either pay this or your mortgage. Richard took a bite of the focaccia. It still took forever to get through the hunk I’d torn off, and my hands froze. I said, “My fingers could break off like one of those corpses holding a clue to their murder.”

Earlier in the day, we’d installed two bookcases in the basement. Richard was arranging the books in alphabetical order. At one time, in New York, the books had been in alphabetical order and every morning I’d walked on Broadway, looking for free samples from the food markets. COVID ended the era of free samples, and now I buy things to eat on Warren Street. The other day I went into a new café. Sun glared from the smile of the woman behind the counter when she said, “All the pastries are gluten-free and vegan.” I wondered if there was something about me that made her happy to announce this or if it had become a cultural commonplace like using the word bandwidth to mean mental space. I said, “I welcome gluten, and I’m not vegan.” She swore I wouldn’t know the difference, and even though I knew she would be wrong, I bought a slice of gluten-free vegan lemon pound cake, which lacked all the ingredients of pound cake. It’s in a bag on the kitchen counter. You can have it.

How we got the bookcases is the mother of a man on Facebook Marketplace had died, and he was clearing out her house. The cases were taller and heavier than reported. Richard wanted me to understand the logistics required to stand up each bookcase and edge it against a wall. He kept saying, “Don’t you see it has to go this way and then that way. Don’t you see it won’t fit from that angle?” I kept saying, “No, I don’t understand, and it thrills me to tell you I will never need to understand, as long as we stick it out together.”

Recently, he found an early book by Louisa May Alcott in one of the free bins on Warren Street. This morning he said, “We didn’t read American literature in school.” (He’s from England.) “Maybe a poem by Longfellow and Moby-Dick.” I said, “Moby-Dick is not chopped liver.” Then I thought that was unfair to chopped liver. If you tasted my chopped liver, you wouldn’t call it “chopped liver.”

I told him about a dream. If I were you, I would save myself and move on from this section. In the dream, we live in a château, and I’m talking to the woman who owns it. First she wants me to take her change and give her dollar bills. Fine. Then there is an enormous platter of lobsterlike creatures. It’s enormous. She holds up one of the creatures, and at first I don’t realize it’s alive. Alive and sluggish. I see the lobsters moving in a jumble on the platter, and I’m horrified for them, for me, for existence as we know it. Why are there lobsters that aren’t quite lobsters!! Why are they so huge!! Then I’m digging in a flower bed, and I think, Ah, it’s time to get the dahlia tubers from the basement. Don’t forget to plant the dahlias. Richard said, “The lobsters are from the zombie apocalypse show we watched with the fungus.” I thought, Yes, and I could see my mind had infinite bandwidth for any old crap fed to it.

A few nights ago, we watched a conversation with Mike Nichols filmed during his last days. He looks emaciated and speaks with his usual clarity and animation. Intercut with the conversation are scenes from some of his films. In one sequence from The Graduate, the camera shoots Dustin Hoffman in his convertible on a California freeway, racing to his future, racing to chaos from a death-in-life torpor—not unlike Saul Goodman fleeing the Cinnabon shop for a life of crime. The camera stays on Dustin’s look of determination, and then it moves to the scenery on his left as he’s racing along, it moves to trees and sky over his shoulder, and then, finally it shoots the road ahead—a tangle of beams and signs and other cars he is driving toward. And I thought that movement of the camera, that layering of shots and the thoughts those shots arouse in the moment and in memory, is exactly what to do with sentences to form a paragraph.

If there were a point to life, the point would be pleasure. I knew a man, an Italian communist, who liked to say, raising a glass of champagne and nibbling a blini with caviar, “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Kafka’s Hunger Artist explains to the overseer at the end of the story he’s not a saint, nor is he devoted to art or sacrifice. He’s just a picky eater. “I have to fast. I can’t help it … I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I should have made no fuss and stuffed myself like you or anyone else.”

I once promised a man who was touchy about his privacy I would keep his secrets, and I kept his secrets. Otherwise I have made few promises, and I have never made a resolution. Today Richard was grumpier than me, and it made me so happy I was nice the whole time we walked. I love my phone. I love the first sip of a cocktail when the elevator drops. There is a woman I don’t love and can’t stop thinking about. I love that I will never understand my connection to her. There is a kind of vulnerability that makes me feel my whole life is stretched out in front of me. In a way, it is.

Laurie Stone is the author of six books, most recently Streaming Now, Postcards from the Thing that is Happening (Dottir Press), which has been long listed for the PEN America Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. She writes the “Streaming Now” column for Liber a Feminist Review, and she writes the Everything is Personal substack.

January 31, 2023

All Water Has a Perfect Memory

I have seen the Mississippi. That is muddy water. I have seen the Saint Lawrence. That is crystal water. But the Thames is liquid history.

—John Burns, quoted in the Daily Mail, January 25, 1943

In the upper left quadrant of Minnesota, a small winding brook and its bubbling waters form the beginnings of a journey from north to south, catching streams and tributaries along its track through the heart of North America toward the Gulf of Mexico. The name given to this massive system made of more than 100,000 waterways is the Mississippi River, a riparian sweep with a drainage basin touching approximately 1.2 million square miles, or 40 percent of the continental United States. With sand and silt ever flowing toward the river’s mouth, a wild wetland of marshes, swamps, and bayous reigns, turning solid land into sponge in the vast network of alluvial floodplains known as the Mississippi Delta. Just under one hundred miles from the Mississippi’s mouth, the river takes a sudden turn southward, snaking east and then north in a final return to its southeasterly course. In this crescent-shaped curvature between river, lake, and gulf lies New Orleans, named after Philippe I, duc d’Orléans by the French Canadian naval officer and colonial administrator Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. In his correspondence with Philippe, Bienville described this magnificent system of watercourses as “filled with a mud as deep as its oceanbed” yet “unmistakably Divine” for its navigational and commercial potential. Through royal decree, Bienville was granted two parcels of land for the establishment of a “new France in this riverside”—land financed by France’s first colonial trading corporation, the Mississippi Company, and cleared and worked by the first enslaved Africans in Louisiana.

Colonization and enslavement have marked the course of the Mississippi’s historical fate, forming an entanglement between the natural conditions of the landscape and the voracious efforts to order the land and extract from it at any cost. The establishment of Black subjugation and enslavement as the guiding principles of the Mississippi Delta’s development commenced with the first-generation European settlers, who constructed no end of plantations along River Road, or the “German Coast,” in the early eighteenth century, as part of a systemic effort to harness the Mississippi’s unique qualities and resources for white landowning rights and profits. This project required decades of collaboration at the micro and macro levels, with parish administrators and Washington pundits, militias of engineers and surveyors, industrial titans, landowners, lawyers, and corporations united in the deregulation, mapping, draining, and domestication of the Mississippi Valley. The abstraction of the landscape into parcels of extractive capital instantiated slave-trading and slaveholding as the political, economic, cultural, and moral “mud and mortar” of the American project in the lower Delta.

These histories and environmental legacies remain visible all over the landscape of New Orleans. They are seen and felt in the imposing framework of the ancien régime grid, which since the city’s founding has divided and segregated rich and poor, free from unfree, white and Black, collaborating with the networks of reservoirs, levees, pumping systems, and public riverfronts constructed along the edge of the Mississippi to keep the edges of it in line. Some plantation complexes where sugarcane was once harvested and processed still stand along the riverbanks of River Road (with a few transformed into sites of public education). In the space between them, petrochemical refineries financed by Formosa, Shell, and ExxonMobil light the skies with carcinogens and toxic smoke above and fluorescent sludge below, their plants constructed on former plantation sites, ancestral burial grounds of Indigenous tribes, and cemeteries of the enslaved. The will to squeeze and strangle the land, the river, and the Black and brown peoples who live and work there goes on, improvising anew across time and space.

And yet, around this moon-formed meeting of water and land, a landscape has come into being through a constellation of resistances to these strategies of control and occupation. Movements and struggles against the tides of commodification persist in the natural and human worlds, both refusing to abide, seeping into the systems created to quell them. This is affirmed each time the Mississippi River spills over its banks. As Toni Morrison rightly reminds us, “they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places … it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” It is also instantiated in each recorded account of marronage, a permanent and common modality of resistance in the Delta wetlands, which turned the swamps into radical sites of commerce and kinship that sustained Black life and education, kept families together, and granted space for escape from enslavement. Revolts gathered up smaller reverberations of rebellion into visible and communal resistance, as on the night of January 8, 1811, when a group of more than five hundred Black people marched from LaPlace in St. John the Baptist Parish toward New Orleans along River Road. Armed with shovels and axes—the tools of their labor—they formed a thick cloud of protection behind their leader Charles Deslondes, an enslaved Creole of color. The historian Walter Johnson’s account of the 1811 revolt lends names and lands to those who participated: among their group were men named Cupidon, Al-Hassan, Janvier, and Diaca; some were American-born, African, or Creole; some hailed from Congo or the Akan; some were Christian, others Muslim. Each were organized into companies that reflected their origins, which together, representing the global stretch of cultures and communities violently destroyed by the transatlantic slave trade, were “dedicated to the single purpose of its overthrow.” Across their journey, they hid in the deep recesses of swamp and river, harnessing their labyrinthine waterways—places they knew and understood better than did their enemies—for protection. The muddy waters of the Mississippi hold these diasporic histories still; like all rivers, their edges are never still.

Far across the Atlantic Ocean lies the 205-mile length of the River Thames, which rises and flows west from Thames Head in Gloucestershire toward Tilbury in Essex and Gravesend in Kent, eventually spilling into the North Sea. Passing Oxford, Reading, and Slough, it cuts thick through the heart of London, offering drainage for England’s lowlands across the way. Shorter, shallower and gentler than the mighty Mississippi, the Thames’s history runs long—it was a catalyst for the organization and development of Europe. With the Roman founding of Londinium in A.D. 47 at a key crossing point over the Thames, the city on the river established itself as a major port and route for domestic trade and exchange, with barges traversing across a system of locks carrying timber, livestock, wool, and food from the fifteenth century forward. By the early stages of empire, the establishment of goods exchanges along the riverbank made the Thames a significant player in the organization of global capitalism and the transatlantic slave trade, beginning with the founding and charter of the Royal African Company in 1672 by King Charles II, which shaped a star-shaped network of transport between the west coast of Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas. A lust for gold quickly shape-shifted to a lust for the land, waterways, and people inhabiting these sources, and inevitable competition and extractive greed would follow as England worked to build an industrial monopoly over the world. Banks on the Thames lent credit that financed the selling and commodification of human beings in colonial empires across the world, before and after 1808. Raw cotton and sugarcane, picked and processed by slaves in New Orleans, found their way to the exchanges in Liverpool, Bristol, and London via naval technologies and water routes invented by British civil servants. The Thames and its connective network of waterways was ever moving, pushing, and circulating goods and human beings by force and by choice into, across, and beyond Great Britain.

Around the curving bends of the River Thames and its tributaries, explosions of resistance have followed and formed, too—shifting, seizing, and interrupting the landscape and its story, the purpose and history of a place. More recently, on June 6, 2020, just twelve days following the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Londoners took to the streets in the middle of a pandemic under the banner of Black Lives Matter. Standing shoulder to shoulder, the protesters edged their way along the Thames from Parliament Square toward Saint James Park and eventually to the U.S. Embassy in Vauxhall, in protest of incarceration and killing of Black people by the police; they paraded in front of the major seats of government and the institutions that have historically profited from slavery and its accompanying industries. In Bristol a day later, on June 7, 2020, an 1895 bronze statue of the British-born merchant and transatlantic slave trader Sir Edward Colson was toppled into the River Avon (a major tributary of the Thames) after decades of efforts, in recognition of Colson’s lucrative participation in the slave trade and the city’s subsequent whitewashing of his legacy as a philanthropist. Questions of accountability, transparency, and historical awakening remain the calling of all activists committed to liberation struggles.

One of the words that the artist Helen Cammock uses to describe her practice is seepage—a slow but steady escape or drainage of one thing into another, a cycle of movement backward and forward akin to the dances of a tide. Linking her process to the condition of water—as her work is forever expanding and leaking into and out of many material genres and modes—Cammock points to the animus at the heart of her project: movement, whether historical, political, geographical, or cultural. Finding and nurturing the sites of shift and movement—the places where they come into contact, pose gaps, interrupt, form connections, become liquid—remains Cammock’s most powerful methodological tool both inside the archives and in the materialization of her films and writing. Harnessing the power of water, the churn of history, and the spirit of memory that haunts them both, Cammock seeps and soaks into historical record, offering and opening space for the flow and traces of the past to link, return, and remember.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are stills from Helen Cammock, I Will Keep My Soul, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023. Images courtesy of the artist and publishers. All rights reserved.

Collaged archival materials used in Helen Cammock’s I Will Keep My Soul, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist, the publishers, and the Amistad Research Center.

Helen Cammock is a British artist who uses film, photography, print, text, song, and performance to examine mainstream historical and contemporary narratives about Blackness, womanhood, oppression and resistance, wealth and power, and poverty and vulnerability. She was a joint recipient of the 2019 Turner Prize and has exhibited and performed her work in galleries and museums across the world.

Jordan Amirkhani serves as the deputy director and curator of the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art & Thought. Her recent curatorial projects include Troy Montes-Michie: Rock of Eye and the 2021 Atlanta Biennial at Atlanta Contemporary. Her writing and criticism have garnered her a 2017 Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Short-Form Writing Grant and three nominations for the Rabkin Prize in arts journalism.

From I Will Keep My Soul by Helen Cammock, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023.

January 30, 2023

The Couch Had Nothing to Do with Me

Years ago, while on assignment, I interviewed a man who spent what felt like hours showing me pictures of the various couches he was thinking of purchasing for his new home. The couches were ridiculous and abstract, as if the practical thing had been replaced with the idea of itself. They were long and narrow and metallic, or otherwise bulbous and overstuffed, like flesh permanently impressed by the tight grip of a corset. I thought he was deploying the couches as a kind of symbolic shorthand–to indicate to me his wealth and his taste, which obviously exceeded my own.

Now, years later, as I find myself in the midst of furnishing my own new home, I recognize in our exchange the telltale signs of a psychology that has been corrupted by the existential problem of populating an empty space. Obsession, fixation, compulsive confession: these weren’t the symptoms of a big ego–they were the symptoms of an ego that was being dissolved by interior design.

In November, on my first night in a new apartment, I became convinced that I needed a white couch, and that everyone in my life who had ever tried to dissuade me from buying one was simply hindered by their own neurotic insecurity. The only people who worry about stains, I told myself, are the people who lack the self control not to make them. My former roommate, very politely, encouraged me to look at my white clothing as an indicator of the fate of my would-be white couch: all of it was spotted with brown or yellow or red or green, a personal ledger of every meal I had ever eaten. I told myself that a shirt had no relation to a sofa, and that the way I acted in one relationship with an inanimate object (neglectful, lazy) had nothing to do with the way I would act in my relationship with the next (attentive, caring, precise).

The next day, I drove to Beverly Hills and bought an immaculate slip-covered couch from a woman from the internet named Lina, who described, in careful detail, the couch’s requisite grooming routine. She seemed to feel that the couch’s covers had grown used to their pampering–monthly laundering, bleaching, steaming–and in fact depended upon it to maintain their identity. Somehow, she made it all sound so easy, the way a dentist can make even a herculean feat like flossing seem fundamental to the longevity of humankind. I didn’t know how to use bleach, and I didn’t own a steamer, but I was confident I would find the means to provide the couch with the conditions it needed to flourish. On Lina, I used the language I had been instructed, years before, to use on the volunteers who head dog adoption agencies: I wouldn’t change the couch to fit into my life; I would change my life to make room for the couch.

I paid two guys to carry it up three flights of stairs and into my living room, where I hoped we would live happily ever after. But in the context of all my other stuff––the books, letters, plants, and out-of-use chargers that I had collected over the course of many years–the couch looked offensive, idiotic, devoid of culture. (Even now, as I try to remember its color, all I can think is: blank.) When the room was empty, it had been full of potential. Now that it housed the couch, its fate seemed rigid and determined, but simultaneously vacuous, like the unending journey of a plastic nub floating in the wide-open sea.

The couch had nothing to do with me, and so I tried desperately to force it onto someone else. I divided everyone I encountered into two camps: people I respected, and people whose taste I judged to be compromised enough that they could be convinced that the couch was precious and necessary––that they wanted, and in fact needed, to take it out of my life and into their own. At parties, on the phone, and over text, I started speaking in the equivocating language of Craigslist ads, which quickly morphed into the lobotomized language of bad break ups: the couch was beautiful, but it didn’t work in my space; I loved it, but was no longer in love with it; it wasn’t it, it was me.

The couch was me, which was part of the problem: it reflected back to me how little I knew about my own desires, and then shamed me for allowing a mass-produced object to become a vessel for my sense of self. I feared I was losing my originality, that I was simply a replica, born to repeat my parents’ worst mistakes (they had raised me with some of the ugliest couches in the world). It didn’t help that my father, when I had asked him for his opinion on the couch before buying it, told me that it reminded him of the one he had just bought himself: “kind of uncomfortable. wouldn’t recommend it for you.”

For the next month, I posted ads on Craigslist, OfferUp, and Facebook Marketplace, but whenever it got to the point that someone agreed to come pick it up, I became convinced that they were only interested in the couch insofar as it provided them a practical means of entering my life for the express purpose of ending it. So, I would stop responding, and then begin telling myself that my life was more important to me than my dislike of the couch––that I could grow to love it, and even persuade it to change. Sawing off the legs, dying the slip-cover: both seemed like potentially groundbreaking alterations. But I never altered anything, and so the couch remained pristine, tidy, and white: an emblem of all of the bad decisions I had made in my past, was making in the present, and would continue to make long into my meaningless future.

Eventually, just after Thanksgiving, a young woman messaged me, telling me that she hoped to buy the couch for her mother, that it was––in fact––just the thing her mother had been looking for. Her story, like the rest, seemed completely implausible to me. But I gave her my address anyway. She would come to my apartment on Tuesday, and I would either survive the interaction or I wouldn’t, but in both scenarios something, mercifully, would cease to exist: myself, the couch, or my infatuation with it.

Maya Binyam is a contributing editor at The Paris Review.

January 27, 2023

Intuition’s Ear: On Kira Muratova

Still from Anya Zalevskaya’s Posle priliva (2020). Courtesy of the director.

In the fall of 2019 I was newly living in the Midwest. In my free time, I’d take long, aimless walks, trying to tune to the flat cold of the place. On one such walk I got a call from my friend Anya Zalevskaya; she was in Odesa, she said, working on a film, a documentary about the Ukrainian (but also Romanian, Jewish, and Soviet) director Kira Muratova. When Anya called, it was almost midnight in Odesa. She was sitting on a bench by the Black Sea; I could hear the waves, the inhale of her cigarette. What film of Muratova’s should I watch first? I asked her. Ah, she said, The Asthenic Syndrome, for sure.

1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism.

The film is really two films. The first, in black and white, opens out into a funeral. It’s for the husband of Natasha, we learn—a middle-aged woman possessed, in the ensuing scenes, to the very end of herself with grief. Because grief invents the road it travels, Natasha—like her audience—does not herself know what she will do next. With terrifying speed, she quits her job as a doctor, insulting coworkers in the process; takes a drunk home, tells him to strip, beds him; shoves and insults passersby. All this is captured in the camera’s eye, however, with a disinterested dignity. And then, abrupt as Natasha’s shoving, the first film breaks into the second (I’ll leave you to see the how and the why—it’s great).

At the epicenter of the second film is the exhausted Nikolai, a schoolteacher who nods off in moments of emotional intensity. Occurrences flare up around Nikolai like religious antimiracles—a carp torn apart by female fingers as “Chiquita” plays, a high school boy imitating a game show host, the agonizing panorama of the dog pound. This is the social and inner world in abjection, yes: but because abjection is possible, the film seems to say, so is human dignity. The question of dignity binds the viewer to the film’s concern: what is the human when it is shorn of category, of psychology, of system? What are we when we are together? What are we when we are alone?

In the rare interviews she gave, Muratova often mentioned her philosophy of film: what she called dekorativnost’ (ornamentedness) and sherokhovatost’ (roughness). (Thanks to Mikhail Iampolski’s 2021 talk “A World without Reality” for many of the Muratova quotes here.) The viewer, Muratova thought, should encounter the film’s reality as an ornament, a woven carpet, a fabric: completely antisymbolic, and thus anti-ideological; completely antipsychological, and thus antistereotypical. Reality itself, she argued, can only be looked at, admired—not interpreted, understood, or possessed. Reality doesn’t “mean,” it is. As when, in an interview, Muratova is asked: “What do the horses in your films symbolize?” To which she replies: “What do the people symbolize?”