The Paris Review's Blog, page 67

December 21, 2022

Today I Have Very Strong Feelings

Manuel C., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

A month ago, Gianni Infantino, the president of FIFA, made his now infamous “I am Spartacus” speech at the World Cup’s opening press conference. “Today I have very strong feelings, today I feel Qatari, today I feel Arab, today I feel African, today I feel gay, today I feel disabled, today I feel a migrant worker,” he said, before adding, “Of course, I am not Qatari, I am not an Arab, I am not African, I am not gay, I am not disabled. But I feel like it, because I know what it means to be discriminated, to be bullied.” Two days before Sunday’s final, he returned to the microphone to announce, a bit prematurely, that this had been the “best World Cup ever.” It pains me to say it, n terms of pure football, and especially given the galactically great final—a game that will remain, as everyone pretty much agrees, unsurpassed in the annals of football history—he was right on the money.

At the beginning of England’s penalty shoot-out against France in the quarterfinals, English fans were back at the Battle of Agincourt, the whole country ready to channel Laurence Olivier or Kenneth Branagh and “cry ‘God for Harry, England, and Saint George,’” when the local penalty pathology kicked in. In the 1996 Euro, Gareth Southgate, currently England’s manager, had famously missed a vital penalty against Germany, weakly side-footing the ball toward the goal. The next day one of the tabloids ran the unforgiving headline “‘HE SHOULD HAVE BELTED IT’ SAYS SOUTHGATE’S MUM.” This time, Harry Kane did belt it. The result was the same. Kane’s ball went way over the bar, effectively ending his country’s chances of beating France in the quarterfinals. England had probably otherwise deserved the win, on the merit of its second-half performance and in the wake of some egregious decisions from the referee Wilton Sampaio, along with the mystery that is VAR (video assistant referee). All the bells say: too late. This is not for tears. Harry lifted the top of his shirt above his chin and bit down on it.

Harry Kane is in good company. All the greats have missed completely or have had penalties saved, including Messi in this World Cup and the last one, and Ronaldo in 2018. But at least they were the obvious choices for the job. Harder to figure is why Virgil van Dijk, one of the world’s truly dominant center backs but not particularly well-known for his goal-scoring abilities, insisted on taking the first penalty for the Netherlands in their shoot-out against Argentina this year. No doubt he wanted to play the captain’s role, steady his team’s nerves, and lay down a marker for the rest of them. The heart has reasons of which reason knows nothing. But I retract my criticism. The miasma of despair that hangs over missed penalties is the cruelest epilogue a game can have.

Only the fourth-ever African and first-ever Arab team to make the quarterfinals, and the first of both to make the semis, Morocco was the darling of this tournament. Playing with guts, flair, and imagination, and led by an unflappable manager in Walid Regragui, Morocco dispensed with those colonizers Belgium, Spain, and Portugal (was there ever a more towering header than Youssef En-Nesyri’s against Portugal?) before coming up against France in the semifinals. The Moroccan team played their hearts out: Jawad El Yamiq’s splendid first-half overhead kick hit the post; Azzedine Ounahi, who was superb all tournament, had a shot cleared off the line; several times Kylian Mbappé took off on one of his electric runs down the wing, he was upended by a hard, effective, borderline-yellow-card tackle. In the end, however, as with Messi in Argentina’s semifinal against Croatia, the superstar had the last word: Mbappé dinked past defenders in the box before laying off a pass for Randal Kolo Muani to finish for a 2–0 France lead. The great sea of red and green in Al Bayt Stadium, borne up on the tidal wave of global support for the underdog, worked itself up with whistles for France and chants of siir! (go!) for Morocco, as if to prove conclusively that a state of wild frenzy can be achieved without the consumption of alcohol. But France held on.

Like Germany after their armband demonstration, Morocco’s national team hasn’t shied away from using its moments in the spotlight to highlight a political position: in this case, support for Palestine. In what the left-wing Israeli newspaper Haaretz described as “a wake-up call,” Morocco’s team unfurled a Palestinian flag on the pitch after each of its wins, delivering a pointed reminder to Israel that, despite the Abraham Accords, the Arab street is playing against them.

The third-place game is one about which nobody usually cares at all, including, it often seems, the players in it. But this time was different: Morocco and Croatia were both beautiful losers, each for their own reasons. Croatia, runner-up to France in 2018, was playing for its third top-three finish, an extraordinary achievement for a country slightly smaller in size than West Virginia. Morocco was playing to cement the respect it had already won. The result was a game that stayed chippy until the very end, when Croatia ran out winning 2–1.

And then, of course, there was the final. 3–3 at the end of extra time; two goals from Messi, plus an impudent flick that set off the graceful move that culminated in Di María’s goal; from Mbappé, a volley of mind-blowing velocity and accuracy, plus a hat trick, the first in a World Cup final since Geoff Hurst’s in 1966. Eighty minutes of dominance by thirty-five-year-old Messi and Argentina; ten minutes of brilliance from twenty-three-year-old Mbappé. Who among neutrals didn’t want Messi, appearing in his fifth World Cup without winning any, to emerge victorious from the penalty shoot-out? This year he’d scored at every stage of the Cup, and now here he was, calmly placing the first penalty past Lloris. As for Mbappé, a hat trick and nothing to show for it: that’s cruel and very unusual punishment. After the game, Emmanuel Macron made his way to the field and attempted to console his country’s hero, who very much looked as if he wished to be left alone—but a photo op is a photo op; Macron wasn’t going anywhere. Meanwhile, the emir of Qatar draped a black bisht, the Arab cloak worn by a person of high regard, over Messi’s shoulders, before handing him the trophy.

Every monarch must have a court jester, especially at carnival time; in this case, Argentina’s goalkeeper, Emiliano Martínez, stepped up to fill the role. Martínez had made a series of spectacular saves throughout the tournament, including two penalty saves in the quarterfinal against the Netherlands, and in the final, a sensational save on a shot from Randal Kolo Muani to preserve the 3–3 score in the last moments of extra time, and then one more in the shoot-out. This save, on a shot from Kingsley Coman, was followed by an inimitable jester’s dance culminating in a moment of slapstick when Martínez chucked away the ball as Aurélien Tchouaméni was approaching to place it on the penalty spot. Tchouaméni, his mind indubitably screwed with, missed. After receiving the Golden Glove—its trophy a large gold glove on a plinth—for best goalkeeper in the tournament, Martínez demonstrated his gratitude by lining it up on his body as if it were a giant erection. There was an audible “Oh no” on FOX Sports before the cameras cut away, and, on the BBC, a more concerned “No, don’t do that, Emi. Don’t do that.” Unfazed, Martinez told the Argentine radio station La Red, “I did it because the French booed me.” The picture, naturally, has gone viral.

At the final whistle, the streets of Argentina filled with fans, and more or less everyone on the globe outside France, both drained and delighted, celebrated Messi and the magic he’d woven in Lusail Stadium. Meanwhile, FOX couldn’t wait to cut away to a dull, irrelevant NFL game, quickly shifting the trophy presentation to their subsidiary station FOX Sports 1. In a perfect coda to the event, it was announced that England had won the “Fair Play” Award and that, for the first time ever, not a single English fan had been arrested during the tournament. We are such stuff as dreams are made on.

Jonathan Wilson’s new novel, The Red Balcony, will be published by Schocken in February 2023.

December 19, 2022

LSD Snowfall: An Interview with Uman

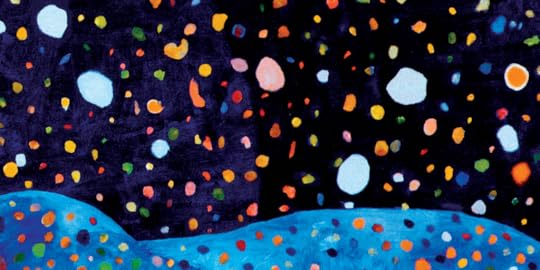

Uman, Snowfall: winter in Roseboom #4, 2016–2020 (detail).

The Paris Review‘s Winter issue cover, Snowfall: winter in Roseboom #4, by the artist Uman, looks from different angles like a field of floating Christmas lights, a confetti drop on New Year’s Eve, and a winter storm touched with a kind of bright magic. Uman worked on it over a period of four years, dabbing bright color on the canvas until, as they told me in our conversation, it felt a bit like “the mothership.” Born in Somalia in 1980, they grew up in Kenya and moved to Denmark in their teens. In 2004, they came to New York, where they continued to work in collage, painting, and sculpture before moving upstate. They are largely self-taught, and their signature style is bright, geometric, and vivid. We talked about their economical attitude toward paint, the process of making Snowfall, and their sheep.

INTERVIEWER

Have you always thought of yourself as an artist?

UMAN

I certainly drew as a kid. The earliest drawings I remember doing were on my actual schoolbooks. At school I ended up drawing on desks and lots of walls, sort of like tagging things—always female figures. I wanted to study fashion. In Kenya our TV channels were limited, but we had CNN, and on Saturdays I would watch Style with Elsa Klensch. I just remember being fascinated by fashion—drawing things, making things out of my imagination. And it felt really good. At one point, my parents were called to my school to pay for the damages I’d caused. I realized then that drawing wasn’t something I should be doing, so I became more secretive about my creativity.

INTERVIEWER

How did your childhood and upbringing influence your art?

UMAN

I grew up in a Muslim culture. To this day, I talk to my dad and he says, “You know, you can do Islamic calligraphy.” And I say, “No, I’m a painter, Dad.” But he doesn’t get it. The place where I grew up, Mombasa, is right on the Indian Ocean. It was the very opposite of Somalia for me. It’s very, very culturally rich, but I wouldn’t say art is valued. It’s just there. One memory I have is of how beautiful the doors are. The mosques and old homes have these beautiful doors with carvings, and I was just fascinated by them. I didn’t go to any museums until later in my life. My first-ever understanding of art was when I moved to Europe and visited my aunt in Vienna. She took me to a museum then, when I was seventeen.

INTERVIEWER

Was coming to New York in your twenties a big cultural shift for you?

UMAN

I struggled a lot. I lived a very adventurous life when I first came to New York in 2004. I was young, I was having fun. I was always out meeting people, staying with friends and strangers, going to different boroughs. I used to sell my paintings in Union Square on the weekends sometimes.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have a studio?

UMAN

I found different places where I could paint. Then I met my friend Kenny, who had a space on Fourteenth Street. I bartered with him: I would give him a painting and he would let me store my work in a little attic that he had in his building. I would paint on the roof. Kenny’s building is three stories high, and there were construction workers working on the taller building next door, watching me below them. They would say, “How much do you want for that?” I sold a portrait of an elephant to one of the guys for twenty-five dollars. That’s the gist of what I used to do. I sold what I could to make money. I sort of had to invent and make myself into who I am today. I actually still have a mural in Kenny’s building.

One of the best things about being in New York, or living in New York, was meeting really good people who loved me and protected me and cared for me. I met this woman named Annatina Miescher who started a garden behind Bellevue Hospital, in a space that used to be a parking lot, right by the FDR. That garden still exists. I would go there and work with her, and the hospital gave me a stipend—twenty bucks, sometimes forty bucks. We made mosaics and we turned this parking lot into this beautiful garden. I planted a wisteria tree that’s really tall now.

Annatina was always a champion of my art. She was connected in the art world and had this idea that if Matthew Higgs saw my work, something could happen. And when he did, he gave me a show. In the summer of 2015, he said, “We are going to do a September show.” That’s how my career started.

INTERVIEWER

What’s your studio like now?

UMAN

It’s very hard for people to get to my house in Roseboom. It’s on a seasonal road, it’s on top of a mountain, and it’s always cold, it always snows. It’s the most beautiful scene but I haven’t been able to get people to come to studio visits there, which is very frustrating, so in late 2020 I got a separate studio in Albany. That’s where I work now. It’s an hour and a half from my actual home, but I set myself up so I can sleep here. After my call with you, I’m going to drive home to Roseboom and be there for the next two days and then come back to the studio on Wednesday.

INTERVIEWER

Do you like living upstate? Do you have any animals?

UMAN

Oh my goodness. I have a long history with animals. I had sheep at one point. I had to give up my sheep after one winter because it was so tough—I realized I couldn’t take care of them. I’d lost one of my sheep, and it was the most painful thing to deal with because they’re almost 150 pounds. It was really traumatizing. I realized it was going to be too difficult for me to raise them and also have a painting career. It’s a lot of work. I have chickens right now. I don’t know exactly which chicken is which—I stopped naming them after losing a few—but I know that I have this love for them.

INTERVIEWER

Do you paint every day?

UMAN

I work every day in some fashion: manifesting, cutting things, sewing, collecting. Sometimes I sit around and stare at these paintings. I work a lot, but not in the way you would think. I don’t stand on my feet painting for eight hours. It’s a very slow, very gradual process.

INTERVIEWER

Do you go through a lot of paint?

UMAN

I’m very, very economical. I was going to say cheap, but no, I’m not cheap. I’m just very stingy. There are oil paints in my studio that I’ve had for over ten years. I squeeze out just a little bit of paint at a time. If you go to some other artists’ studios, you will notice that the floor is covered in paint. My place looks like a lab. I don’t like wasting paint, and I don’t like having a messy studio.

INTERVIEWER

How many paintbrushes do you have?

UMAN

I’m not very attached to my paintbrushes. I know people who have kept brushes for years. At one point, I would use a brush for just a month before switching to a new one. In fact, Annatina used to tell me, “You always waste brushes.” I use a brush to the end of its life, but I go through them quickly.

INTERVIEWER

Your practice includes sculptures, collages, drawings, and found objects, but now you mostly paint. Is it the medium you’re most drawn to?

UMAN

Painting, to me, is like playing music for a conductor. It just feels natural. It’s something I can control.

I eventually want to go back to collage. I just got bored with it. I believe I did certain collages really, really well, to the point where I feel like a lot of people imitated me. Many, many artists are appropriators of self-taught artists. They come and see something, and they use it to their advantage. I want to tell them, Please go out there and make something original. You have to push yourself and make honest work, not work that tries to look like somebody else’s work. That’s my biggest pet peeve: people who have no originality and take things from artists who are marginalized—outsider artists—and end up gaining something from it.

INTERVIEWER

What was the process of making Snowfall like? You worked on it for a long time, right?

UMAN

Yes, but not continuously. First I started stretching the canvas, then I prepared it. It’s a really big one—ten feet long. It sat in my studio and I worked on it for several years. Each little color in it was left over from another painting I did. At first I painted just pure snow—white dots all over. And then I said, Let me just add colors to it. It became like an LSD snowfall. It would sit in the corner while I was painting three or four other paintings, and I would go back and forth between them. For a few years I would touch Snowfall with whatever little color I had that I thought made sense. I’m very instinctual, so I don’t know—something about it just drew me back. At some point, I thought, This is done.

INTERVIEWER

Snowfall influenced the painter Matthew Wong, who died in October 2019.

UMAN

Matthew was such a great painter. One day he sent me a message on social media and that was the beginning of our friendship. He came to me and said that he loved my work. Meeting him left me euphoric, left me confident. It changed me. It felt very invigorating and validating to hear that from another artist. And we shared ideas—I sent him images of what I was working on, and he sent me images of what he was working on. He was very encouraging, very supportive. I really, really wish he were here.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think Snowfall is different from your other work?

UMAN

It’s a mixture of realism and abstraction, because in a sense it’s really that view I have in Roseboom. Just hills and hills, and then sitting on top of the hill where my house is, you can see these valleys and they’re part of what’s called Cherry Valley. This painting inspired a lot of paintings I did after it. It’s sort of like the mothership.

Camille Jacobson is the engagement editor at The Paris Review.

December 16, 2022

What the Paris Review Staff Read in 2022

From Mary Manning’s portfolio Ciao! in issue no. 242.

The sadness of thinking about a year in reading is how little of it endures! As I try to recover lost time by rereading the terrible handwriting in my journal I find so many abandoned or forgotten books, and even the ones that remained in my memory are now reduced to an image or a sentence or a feeling—but maybe this is universal, and therefore not so sad.

The book that stayed with me the most this year was Tove Ditlevsen’s The Copenhagen Trilogy, not just because of how moving it is and how it performs such relentless moves with doom as she details her struggles with external demons (family, class, addiction) but because I still don’t understand exactly how she accomplished this. Whenever I’ve tried to define it in conversation, I end up saying something hopelessly abstract, like, “The series invents its own authority.” This hopelessness made me want to come up with a corresponding new aesthetic category, something that would precisely and permanently define the compulsive.

In a very different mode: I keep remembering images from Jean-Patrick Manchette’s crime novels, which I read this summer in some of NYRB Classics’s reissues. My favorites, perhaps, were No Room at the Morgue and Nada, which aren’t so much noirs as rapid phenomenologies of politics. There are dense technical descriptions of guns and scenes of people waiting in dark rooms, but operating through these minute details is a sense of a larger system.

These, I’ve realized sadly, are the memories of reading I’m left with now. But maybe this awareness of forgetting has been prompted by an experience I loved at the beginning of the year—listening, online, to Alice Oswald’s lectures on poetry at Oxford. The first, from 2019, is called “The Art of Erosion,” and uses the seventeenth-century poet Robert Herrick as an example of a writer with a way of working that she admires. It wasn’t only her argument about poetry and erosion that I found both moving and invigorating, her idea that there is a poetry that builds up and a poetry that uncovers or erodes; it was the use of Herrick—someone so apparently outmoded and forgotten!—as her model for thinking through those subjects. Of course, I’ve forgotten many other aspects of those nighttime lectures. So much is already eroded at the moment of listening, or reading. How any writer makes something survive—even for a year—is still a mystery.

—Adam Thirlwell, advisory editor

My friend Charlotte and I often attribute moments of temporary insanity to the effects of seasonal change. This is kind of a joke, kind of not, but in any case I’m from New England, I’m obsessed with the seasons, and so when I recall what I read this year I also remember the changes in the weather.

1. Winter: Sick with COVID on Epiphany, during one of New York’s only snowfalls, I read Painting Time by Maylis de Kerangal. It was not an easy book—long, heavy sentences and little action—but I kept returning to de Kerangal’s gorgeous, breathless, breath-giving descriptions of painting sets for theaters and for movies. Her narrator is even tasked with recreating a replica of the cave paintings in Lascaux, a project that de Kerangal imagines in luscious passages that illuminated something for me about artifice and art.

2. Spring makes me sad, despite all the flowering trees, because I paradoxically associate it with endings. (The school year, and the sad part of the Resurrection story.) Delayed for hours in the airport in San Francisco, feeling the kind of frightening misery that settles over me fortunately rarely, I read a book of Raymond Carver’s short stories back-to-back. This isn’t something I would recommend.

3. In July I got around to reading my Christmas present from my friend Rebecca: John Williams’s Stoner! I was totally absorbed in this quiet portrait of one man’s consciousness, from cradle to grave—there’s no other book quite like it, is there? This was almost certainly a book for a different season—the descriptions of the crackling frost and the streetlights in Missouri winter cast a long shadow over my memory of it—but instead I finished it on the roof of the Ace Hotel in Los Angeles in August, so hot, waiting for someone to meet me. I will never forget my favorite sentence: “And so he had his love affair.”

4. While in Boston over Thanksgiving, wearing too light a coat for the chill and feeling restless, I picked up The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford at a new bookstore on Charles Street. Immediately I was laughing. It’s so indisputably English! It’s biting in its satire and yet fundamentally warm—there’s a kind of sharp joy that felt compatible with November coziness, and that made it seem like the right thing to read as the year draws slowly and suddenly to a close.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

A Dance to the Music of Time may have temporarily ruined my life. Not only did it turn me into an insufferable person whose main subject of conversation was a little-read twelve-volume novel cycle about interwar Brits, but it made all other books read like thin gruel. Anthony Powell’s novel follows a young man and his school friends from late teenagedom through middle age. We watch them try to achieve writerly fame, sleep around, conjure Marx with a Ouija board, start leftist literary magazines, and go to war. What interests Powell aren’t people bonded together by strong ties like marriage but all the people who are usually cut out of novels in service of the central relationship: friends’ exes whom one keeps running into, parents’ pals with whom one must establish uneasy adult discussions, professional nemeses, golden boys gone bad. Because it leaves room for these awkward encounters, second divorces, and the chance that what someone thinks is their most secret love affair is actually all anyone else can talk about, the book is among the most lifelike things I’ve ever read.

In my work as a journalist, I’ve been thinking more and more about how traditional reporting, which often focuses on a single exemplary person, can never be entirely true. No one, no matter how powerful or famous, is actually operating alone. Powell’s novel is the first literary work I’ve read that maps out what a social life actually looks like: byzantine, random, and usually embarrassing. Powell is often compared to Proust, because both authors have written long books and have last names that start with P. But his purview is nothing like Proust’s. He doesn’t care about his narrators’ thoughts. Powell’s is a world of exteriors. He wants gossip.

—Madeleine Schwartz, advisory editor

For me, 2022 was a year of historical fiction. The farthest back my reading took me was the twelfth century A.D., via Lauren Groff’s Matrix, a tale of nun-power that thrills though it occasionally steers close to corny (this is the danger of historicals, particularly the swashbuckling type). Stay for the reinvented Pentecost scene, with hot flashes standing in for tongues of flame. The nearest it took me was the nineties, through Elif Batuman’s Either/Or, which includes the trappings of that era—Alanis Morissette, The Usual Suspects, cottage cheese diets—but, in its rendering of campus “romance” and the attendant anxieties, took me back to my own college experience in the early aughts (Death Cab, Kill Bill, the South Beach Diet). My favorite book I read this year, though, was Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch by Rivka Galchen, set in seventeenth-century Germany. Despite the title, it’s a quiet book: accused of witchcraft, Katharina Kepler, a slightly Olive Kitteridge-like character, goes about the defense of her life and reputation (which are the same) in a matter-of-fact if not always practical way, keeping appointments with bureaucrats. Meanwhile, life goes on for her and her family and neighbors; they go to work, they spend time with their cows, they dab makeup on their acne. Chilling how like us they are, as they bumble toward a killing. The gem of the novel is Simon, Katharina’s widower neighbor, who “firmly believe[s] that the life of a spinster is often better than that of a married woman. No dying in childbirth. No beast in the house.” It’s refreshing for an author to allow centuries-old characters real insight into their own time, rather than assigning them the beliefs we are told most people had—and this is perhaps the best reason to write about them at all. Like us, they are caught up in absurdities that turn to atrocities; like us, they know it.

—Jane Breakell, development director

This year seemed very long to me, though not in a bad way—it just kept adding new chapters. The longest book I read, which also took me the longest to read, was Dickens’s Bleak House, which I began in January but didn’t finish until October. I doubt most people read the book to learn the outcome of Jarndyce v Jarndyce;what I remember most is its flood of indelible “flat” characters: Mrs. Jellyby’s maniacal humanitarianism, the delusional “deportment” of Old Mr. Turveydrop, the obsequiousness and ambition of Mr. Guppy. I read all kinds of books this year, but I was drawn to the ones that, in the spirit of Bleak House, overflow—books crammed with people and images and possibilities. Books that remind you there can always be more, and more vivid, life. There was the ramshackle odyssey of Charles Portis’s The Dog of the South; the infinite gradations of flower and fabric and season in Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book; the still deepening roots of Lucille Clifton’s Generations; the rich, devastating twilight of a culture in James Welch’s Fools Crow; the seemingly endless rooms of the decaying Irish hotel (and the endless cats who haunt it) in J. G. Farrell’s Troubles. And, of course, Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day, which enacts the fullness of every second and every stray thought passing. After reading something like that, who wouldn’t want to try to feel their morning, their afternoon, a little more keenly?

—David S. Wallace, advisory editor

In the winter, I joined a small reading group that was being hosted by the Russian poet Maria Stepanova at Columbia University. She guided us in reading intergenerational and autobiographical writings from the Soviet Union and from present-day Ukraine that reveal a different historical narrative than Putin’s. One of them, the Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl, is the most intimate oral history that I have ever read. Alexievich brings together brutal testimonies of the Chernobyl disaster from thousands of interviews with the victims, scientists, and Communist Party members who witnessed it firsthand. The journalistic “I” is nowhere to be found.

I also inhaled Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser, in one bleak fall afternoon. The book-length soliloquy is narrated by a fictional pianist who studies alongside Glenn Gould and lives in the shadow of his musical genius. The prose is propulsive, rhythmic, and filled with Nietzschean ressentiment. I listened to Glenn Gould’s early interpretation of the Goldberg Variations repeatedly as I read, imagining Gould slouched over the piano, just as obsessive as Bernhard’s narrator playing Bach’s arias hours after his listeners had gone home.

—Campbell Campbell, intern

I begin each year committed to documenting my reading with the discipline of an accountant. But by February I’ve forgotten about the existence of my ledger, and by the spring I’ve convinced myself that my memory—partial, unreliable—is a better reflection of the strange communions that happen while reading, which are otherwise cheapened by the determinism of obsessive list-making. The year’s basic plot points, anyway, are easy to recount. For whatever reason, in 2022 I tended to read anthropologically. The winter was all about Scandinavia. I read, in quick succession, Son of Svea and Willful Disregard by Lena Andersson—both excellent—and then Long Live the Post Horn! and Will and Testament by Vigdis Hjorth. By the spring, I was motivated by resentment. I get an addictive, sick feeling reading books about scorned white women in love: a mixture of identification, rejection, defensiveness, and disgust. I indulged that feeling completely in my reading through the summer, and weaned myself off it only in the fall, when I turned toward books about settlers and immigrants in colonial and post-independence Africa. (For research, I told myself, burned by the books I had been seeking out for pleasure.) I read Waiting for the Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee, A Bend in the River by V. S. Naipaul, and then the stunning letters exchanged between Pankaj Mishra and Nikil Saval on the occasion of Naipaul’s death. Of Naipaul’s legacy, Mishra writes: “In retrospect, his analysis of the failings of postcolonial states and societies does not seem unique; it could seem unprecedented only in the West’s intellectually underresourced and politically partisan mainstream press. … Cold-war liberals warmed to anyone who attributed ideological — and therefore suspect — motives to those they deemed illiberal (or knew little about), while claiming perfect rationality for the free world, along with aesthetic and moral superiority.” I didn’t relate to A Bend in the River’s fatalism, even if I found it sociologically fascinating: What is it about the postcolony that enables its interlopers to declare life over? Finally, in November, I decided to combine my two most recent anthropological interests and read books about scorned white women in love in post-independence Africa. I reread the beginning of The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, and am now wading through Mating by Norman Rush, which seems to be having a moment; having read only a third of it, I’m finding myself so far perplexed. I have a troubled preoccupation with the genre, which tends to recycle its set pieces: the promise of good, liberatory sex, usually extramarital, and an ongoing, if out of sight, literal liberation movement on the margins. (The theme of my year in reading, I guess, has been morbid curiosity.) Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North, a reread, was my favorite book of the year, and last year, and probably the year before. The mythic figure at its core—an English-educated Sudanese economist who appears in a small village, disappears just as quickly, and leaves a wake of terror at home and in the metropole—tends to avenge the year’s disappointments.

—Maya Binyam, contributing editor

The best fiction I read this year was Seth Price’s “Machine Time,” published in Heavy Traffic 1 this summer. Most fiction is basically a simulation engine for human emotions and relationships—conversations with imaginary friends, etc—that elides a basic feature of both novels and humans: they are given form—and feeling—by something not so warm and fuzzy, something abstract, like the syntax of sentences or by a social system. Isn’t the human condition also one of relating to the inhuman? The charm of this story—in which a contemporary artist attends a party at the “open-air, Tropical-modern” island fortress of a wealthy character named Trader—is that it filters our world through the stylistic excesses of sci-fi, making it more alien rather than more “relatable.” Price steps neatly between manifesto-like interior monologue and precise prose that renders objects both specific and exotic, like a video game graphics engine: “His family had crossed the room in advance of their wheeled luggage like four new coins rolling across the carpet.” “Machine Time” isn’t magic realism; it is realism for a reality (our own) in which all forms, sociopolitical and otherwise, are in flux. Price’s narrator is in the business of such metamorphoses: he has “designed business envelopes that could be slipped into and worn to a party.” His job, like those of many of us today, is “to express without end.” He’s a creative professional, a bit like the “corporate anthropologist” of Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island, only funnier and more ruthless. He has “discovered that with a slight tilt of the head all the meanings flickered and vanished, and it fill[s] [him] with a vertiginous, darkly ecstatic feeling.”

In winter, spring, and fall I read three mysteries by Raymond Chandler, whose narrator is also an investigator and, inevitably, an instrument, of his times.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

I am decidedly allergic to flowery prose. I take the fact that I’ve just employed an adverb as a sign of personal growth. It’s unlike me to work through a Victorian novel and consider it anything less than a massive chore. But as a reluctant New Yorker, a country mouse confined to a city mouse life, I was drawn to the title of Thomas Hardy’s farmer love-triangle classic. Far from the Madding Crowd. Hardy can certainly wax pastoral; I felt quite at home in the dreamy green acres of that whimsical Wessex kingdom. I also found his joyfully absurd British humor a welcome antidote to a certain post-COVID brand of urban humorlessness that, if I’m not careful, does occasionally infect my own soul.

More in keeping with my usual tastes: Also a Poet by Ada Calhoun, in which she sets out to do what her father, the art critic Peter Schjeldahl, could not: compose the seminal biography of Frank O’Hara. Her project takes a fortuitous turn when O’Hara’s estate refuses to approve. What results is not only a love letter to Frank O’Hara, his charismatic cronies, and the glorious New York in which they lived but a tribute to Calhoun’s relationship with Schjeldahl, and to her feral East Village upbringing. Anyone with a brilliant but difficult father should read Also a Poet.

—Morgan Pile, business manager

I was looking for something to help me cope with a grim January, so I bought a copy of The Group, Mary McCarthy’s 1963 novel. I spent a wintery weekend with McCarthy’s cast of eight Vassar grads as they figure out their burgeoning lives in New York. The book was my favorite this year and stayed with me long after I put it back on the shelf: I reread passages, watched the (terrible) 1966 film, pined after a beautiful first edition, and became obsessed with the book’s public reception, particularly with Robert Lowell’s dismissive claim: “No one in the know likes the book.”

In late spring, I picked up The Spare Room, the first book of Helen Garner’s that I’ve read, in anticipation of our interview with her in our Fall issue. I was moved and inspired by the frankness of her writing—how her spare prose captured the sometimes painful and complicated nature of best friendship.

In the middle of summer, preparing for a trip to Paris, I read Cher Connard, Virginie Despentes’s humorous, ultracontemporary new epistolary novel. In France, whole billboards were taken up by Despentes’s cover art, posters of the book’s cover lined every bookstore window, and Despentes made various television appearances. I felt pleased to have come prepared.

Fall was full of books I started and stopped, until I came across an interview with Paula Fox in our archives and was immediately charmed by her way of speaking, especially when describing the difficulties she’d faced in her young life: “I often thought of killing myself but then I wanted lunch.” The very next day, as though he’d read my mind, my boyfriend gave me a copy of Desperate Characters for us to read together.

—Camille Jacobson, engagement editor

December 15, 2022

The Blackstairs Mountains

Illustration by Na Kim.

In the new Winter issue of The Paris Review, Belinda McKeon interviews the writer Colm Tóibín, author of ten novels, two books of short stories, and several collections of essays and journalism. Tóibín also writes poetry—“When I was twelve,” he tells McKeon, “I started writing poems every day, every evening. Not only that but I followed poetry as somebody else of that age might follow sport”—and we are pleased to publish one of his recent poems here.

The Morris Minor cautiously took the turns

And, behind us, the Morris 1000, driven by my aunt,

Who never really learned to work a clutch.

I remember the bleakness, the sheer rise,

As though the incline had been

Cut precisely and then polished clean,

And also the whistle of the wind

As I grudgingly climbed Mount Leinster.

All of us, in fact, trudged most of the way up,

With my uncle carrying a pair

Of binoculars borrowed from Peter Hayes

Who owned a pub in Court Street.

My uncle surveyed the scene

As far as Carlow with the binoculars,

And up toward the Wicklow Mountains.

And my father, when he was handed them,

Claimed that he could actually see the sea.

But, when it was my turn, all I saw

Was something vague in the distance

That no amount of focusing

Could convince me were foam or waves.

So much chatter and excitement,

My mother wearing slacks and a headscarf

And Auntie Kathleen her sensible shoes,

So much distraction that my uncle did not realize

Until we reached the cars

That he must have left the binocular case

Somewhere, maybe when we stopped

Near Black Rock Mountain on the way down.

The adults all looked worried.

How could they face Peter Hayes, or face

His wife and his sister who helped

Him run the bar, with the news?

Then my brother Brendan said

That he would go back and see

If he could find the case, but my aunt

Was even more against the plan

Than my mother. It would take an hour

To get up and half an hour to get down.

And that was if he ran all the way.

But he looked for approval to my father

And my uncle. He would be quick, he said.

And, so, he set out to bring back the case.

Soon, he was a speck, and then smaller

Until not even the binoculars could find him.

There was worry that a mist could descend,

But it stayed bright, uncloudy. It was one

Of those long July Sundays. We waited.

I don’t know what we talked about

Or what we did. Time passed, I suppose.

All of us worried that he wouldn’t find

The case after all the trouble,

That he would look everywhere

But eventually appear empty-handed.

The adults always had something to discuss.

My father and his brother could talk history

Or hurling or tell stories about old priests.

My mother and her sister-in-law

Could ask the girls about school, the nuns.

And I could watch them. I do that to this day.

But none of us mattered

Against the one who had left us,

Who was still out of sight.

When he returned, pale-faced, silent,

With the case in his hand, he was greeted

By my uncle with a ten-shilling note.

He had found the case where my uncle thought

It had been left: on that wall at the lookout point

A bit below Black Rock Mountain.

As we drove south in our convoy of two

Small cars, no one thought of anything more

Than the night ahead, the day to come.

No one imagined another Sunday, years hence:

He has been found dead, your brother.

You should get a flight home

As soon as you can. In the time the taxi snakes

Toward the airport, and the next day

When I see him in his coffin,

I think of that journey up the mountain,

The single intent, and I imagine my brother

Searching once again for the leather case,

Not seeing it there on that wall, and then looking

All around, defeated, knowing that his climb

On this occasion has not worked out,

And I want him to be assured by someone:

There is nothing to worry about,

Things have changed, most of those awaiting

You are dead: Auntie Kathleen and Uncle Pat,

Harriet and Maeve, our mother and father,

And Niall too. Even Peter Hayes, his wife and sister.

No one will be disappointed.

The binocular case can linger where it will.

Even the binoculars themselves are beyond use.

It is better to take your ease, lie down

In the scarce grass, wait a while,

Close your eyes when night falls, dream

Of what can be seen through a convex lens:

The Barrow, the Slaney, sharp lines

In the landscape, a blur that might be Carlow town,

And fields, folding out for miles,

And then, to the east, what must be the coast,

The soft waves at Cush, the long strand at Curracloe,

But really just what I saw that day through

Those binoculars: something vague in the distance,

A dimness receding, first shimmering, then still.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent book is The Magician.

December 14, 2022

“Security in the Void”: Rereading Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger (second from right), via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

1.

Some people live more history than others: born in Heidelberg in 1895, the German literary giant Ernst Jünger survived a stint in the French Foreign Legion, the rise of the Third Reich, two world wars, fourteen flesh wounds, the death of his son (likely executed for treason by the SS), the partition of Germany, and its reunification, before his death at the remarkable age of 102. Perhaps no historical rupture had a greater influence on his thinking, however, than the rise of industrialized warfare across both world wars. A soldier as much as a writer, Jünger memorably declared in his diaries in 1943 that “ancient chivalry is dead; wars are waged by technicians.” Articulating the consequences of this transformation became the central obsession of his work.

Jünger’s fascination with the ways in which technologically driven projections of power would reshape traditional civilian life and geopolitics has secured his legacy as an unignorable diagnostician of the modern epoch. He is today to industrialized warfare what his contemporaries Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer were to the rise of mass-produced culture: all three drew connections between technology’s assault on the inner life of the individual and fascism’s weaponization of the mob. Yet while Kracauer and Benjamin, prominent voices of the Weimar socialist left, denounced fascism from the start, Jünger was very much a man of the right. Though he continues to be widely read, his significant literary achievements can be contemplated only with ambivalence. He remains one of Germany’s most celebrated and controversial writers—by far the most interesting ever to have emerged from the interwar right.

2.

On The Marble Cliffs, the most famous of Jünger’s novels, was published in Nazi Germany in 1939 and censored by the Gestapo in 1942. It was thanks to Hitler’s admiration of Jünger’s earlier work that it was published at all. When other party officials pushed for its immediate suppression (“He has gone too far!”), the führer reportedly replied: “Leave Jünger be!”

It’s not hard to see why the novel attracted the attention of the censors: On the Marble Cliffs charts the slow infiltration and eventual destruction of a sophisticated, Elysian society by a barbaric forest tribe whose ruthless leader sows anarchy and terror. Set, like all fables, in a distant time of its own, the story centers on two battle-hardened brothers who’ve renounced war, politics, and worldly concerns for a monkish existence as botanists. They live apart from the simmering chaos, high up on the Marble Cliffs.

The novel was immediately received as an allegory for the rise of the Third Reich, but as Jünger points out in a postscript, “People understood, even in occupied France, that ‘this shoe fit several feet.’” In other words, what happened in Germany wasn’t historically unique. Echoes were soon to be found in Axis Italy, Vichy France, and the Soviet Union, not to mention in the nascent authoritarianism stirring within Western democracies today. As Jünger saw it, Hitler’s nihilism was part of a more general crisis threatening modern civilization.

Whatever the politics of the book—and they are nothing if not equivocal (Jünger claimed elsewhere that the novel was “above all that”)—there’s no denying its icy polish. The novel is defined by its fantastical Mediterranean landscape, and we spend much of our time admiring the view. To one side of the cliffs lies the Marina, with its lush vineyards and islands that “float on the blue tides like bright flower petals”; to the other, the Campagna, populated by rough but noble cattle herders, and bordered by the “dark fringe” of the forest, where the forces of anarchy lie in wait. There is much to lose: jeweled lizards, red vipers slithering as if in a single “glowing web,” astonishing orchids, magical mirrors, abundant vineyards, rarefied libraries. This symbology flickers throughout the novel like reflections on a lake, captivating yet shifting, and ultimately eluding fixed interpretation. The imaginary world is at once classical and modern; perhaps this ancient-seeming realm isn’t quite so distant as we thought. There are both automobiles and ballads dedicated to a “gluttonous Hercules,” shotguns as well as Roman stone.

The most striking quality of On the Marble Cliffs is, to me, its stillness. If fiction is the art of lending time to concepts and truths that seem to exist outside of time, On the Marble Cliffs aims for just the opposite. It is an exercise in “draining time,” to borrow the phrase the brothers use to describe the study of botany. Until the frenzy of the final battle scene, the book distills itself to a single suspended moment. The narration hovers over the landscape like a charge in the air. It’s the quiet before the storm, or, in our botanists’ case, before they “fall into the abyss.”

Throughout his oeuvre, Jünger remained preoccupied with this idea of stopping time. One of the few hopeful symbols to appear in the novel is the mythical mirror of Nigromontanus, designed to concentrate sunlight into a magical flame that transforms all it devours into an “imperishable” state, a process of “pure distillation” that takes place beyond the reach of either the narrative or the historical durée. One can imagine that Jünger—who after the Second World War experimented with LSD—viewed On the Marble Cliffs as just such a temporal transcendence, a way of preserving those values that Nazism perverted: chivalry, dignity, knowledge, beauty. It is not a protest novel but, like the mirror of Nigromontanus, a kind of “security in the void.”

3.

This framing of On the Marble Cliffs—the author’s own—complicates the invitation by Jünger’s hagiographers to read it as a political critique, thereby exonerating him of his own far-right leanings. I tend to agree with Jünger that On the Marble Cliffs is not merely an allegory for the rise of the Third Reich. In fact, it’s difficult to extract a sustained political allegory from any of his works.

Jünger’s politics were complicated, if not incoherent. A decorated veteran of the First World War (he made his literary debut with a bellicose, best-selling diary from the trenches, Storm of Steel) who was praised by Hitler but who refused to join the Nazi Party; a self-taught conservative intellectual (Jünger never completed university) who won the admiration of Marxist writers like Bertolt Brecht; an incurable elitist sympathetic to communist centralization (he opposed liberalism above all)—the Weimar-era Jünger projected an aloof, aestheticizing, and ultimately paradoxical strain of fascism. Kracauer captured what feels most damning about Jünger’s political thinking during this time in a review of his controversial treatise The Worker (1932) for the Frankfurter Zeitung, in which he accused Jünger of having “metaphysicized” (metaphysiziert) politics: What about real, tangible action in our own historical moment? Metaphysics is an escape.

These ideological contradictions—or is it political ambivalence?—extended throughout the Second World War. The tendency to view the world through the metaphysical lens of cycles of power as opposed to “right and left” certainly seems to have granted Jünger, then an influential conservative voice, a great deal of moral latitude in distancing himself from the horrors emerging around him. Ever aristocratic, he wrote critiques of Hitler could appear to be as rooted in intellectual snobbery as in moral outrage. He once complained that the Nazis “lacked metaphysics.” They waged war like technicians.

Jünger spent the Second World War as a military censor in Nazi-occupied Paris, where he kept up his ironic circle of acquaintances. His closest companions during this time included the prominent legal scholar Carl Schmitt, a racist and an early supporter of the Nazi Party. Then again, his diaries reveal him to be just as close to the conspirators behind the von Stauffenberg plot on Hitler’s life in 1944. Jünger himself was investigated, but no concrete evidence could be found tying him to the attempted assassination; the main conspirators were executed. There is no doubt he considered Hitler a vulgar yet ultimately indomitable monster. The sheer nihilistic scale of the genocide in Nazi concentration and POW camps crystallized his despair as well as his conviction that more active resistance was pointless. “I am overcome by a loathing for the uniforms, the epaulettes, the medals, the weapons, all the glamour I have loved so much,” he confessed during a brief tour of the eastern front. There’s a reason a quip by Jean Cocteau (not exactly exemplary in his own wartime behavior) regarding Jünger’s conduct during these years endures: “Some people had dirty hands, some people had clean hands, but Jünger had no hands.”

What did it really mean to be hands-on at such a time, when protest often amounted to nothing more than self-sacrifice? It isn’t a question I like to ask. Jünger’s son, briefly imprisoned for dissent, was later declared killed in action in Italy, though the two bullet holes found at the base of his skull suggested an execution by the SS.

The veterans and botanists in On the Marble Cliffs—much like Jünger himself, who studied zoology and spent long afternoons in occupied Paris collecting beetles—also delay intervention until it is too late. They are elegists more than dissidents, hunting for rare orchids as the Head Forester‘s campaign advances on the classical civilization below. Yet the novel contains enough recognizable allusions to the Third Reich that it no doubt took courage to publish it. A torture hut where the Head Forester’s enemies are flayed is modeled on Hitler’s concentration camps for political and social deviants, the first of which were established in 1933; Jünger is likely to have seen prisoners marched past his temporary residence in Lower Saxony. It has been noted that the Head Forester bears a resemblance to Hermann Göring, the notorious commander in chief of the Luftwaffe and himself an avid hunter. Nazism, furthermore, valorized forests and their connection to the German Romantic spirit. The novel’s highs come by way of Jünger’s gift for the chilling aphorism. Of the character Braquemart, modeled on the Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels: “He was of that breed of men who dream concretely, a very dangerous sort.” Its lows follow slips into dour, elitist didacticism: “When the sense of justice and tradition wanes and when terror clouds the mind, then the strength of the man in the street soon runs dry…This is why noble blood is granted preeminence in all peoples.”

To my reading, On the Marble Cliffs is a daring but ultimately inward-looking achievement. It is as if Jünger built himself an ivory tower in which to wait out Germany’s darkest decades. He never left. Nor did he repent. Until his death, Jünger dismissed criticisms of his wartime behavior. As he aged, he appealed to the growing asymmetry between himself and his younger critics: you weren’t there.

On the Marble Cliffs serves as a key to the cosmology Jünger developed in these later years. All the major motifs of this novel—serpents, language, nihilism, chivalry, dreams, Spenglerian theories of history as cyclical—return throughout his wartime and immediate postwar works, most notably the war diaries and the techno-dystopia of The Glass Bees. In the most generous light, they present an argument for the preservation of beauty, refinement, and human dignity in the face of Armageddon; in the harshest, a justification for a retreat into aesthetics and abstraction in the face of all-too-real atrocities. I recommend reading On the Marble Cliffs at different times of day, with both approaches in mind.

And what would I send through the Mirror of Nigromontanus, I wonder? Surely there’s nothing so dangerous as an aphorism concrete enough to catch its own reflection. Anyway, here’s one for the void: an enduring sense of nobility, stripped of a politics, sets its own traps.

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is the author of the novels The Exhibition of Persephone Q and The Visitors. Her first short story collection is due out from And Other Stories in 2023. This essay is adapted from her forward to On The Marble Cliffs, which will be released by the New York Review of Books Classics in January 2023.

December 13, 2022

A Letter from the Review’s New Poetry Editor

As a new member of the Review’s team, it gives me great pleasure to bring you several equally new contributors in our new Winter issue. Some are celebrated literary artists, some are emerging voices, and others fall somewhere in between. Perhaps the most lofty among them is William of Aquitaine, also known as the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and the Count of Poitou—the earliest troubadour whose work survives today. For all his lands and eleventh-century titles, there’s a slapstick vibe to this unwitting contributor’s bio that I can’t help but find endearing. Excommunicated not once but twice, and flagrant in his affairs and intrigues, William survived more ups and downs than most modern politicians could ever pull off, and in Lisa Robertson’s agile translation, he speaks to us from the end of his earthly tether: “I, William, have world-fatigue,” he sighs across the centuries.

Much of my new job involves sifting through the slush pile for unexpected gifts—so you can imagine how tickled I was to see the world-weary troubadour dust himself off once again in another poem, by Luis Alberto de Cuenca, titled “William of Aquitaine Returns,” translated into a measured and colloquial English by Gustavo Pérez Firmat:

I’m going to make a poem out of nothing.

You and I will be the protagonists.

Our emptiness, our loneliness,

the deadly boredom, the daily defeats.

The legendary Tang Dynasty poet Tu fu also makes a debut of sorts, in an extended excerpt from Eliot Weinberger’s forthcoming “The Life of Tu Fu,” the “fictional autobiography” of a poet who witnessed the violence, famine, and displacements of civil war in eighth-century China. “Is there anyone left, under a leaking roof, looking out the door?” the poet asks. “They even killed the chickens and the dogs.” Weinberger’s wry, oracular Tu Fu describes a world that feels painfully familiar; it might be Ethiopia, Myanmar, or any number of modern conflict zones.

Elsewhere in our pages, the Ukrainian-American poet Oksana Maksymchuk sends an update from her own war zone, awaiting an enemy’s barrage of propaganda in a cellar lined with strawberry jam; from the couch, C. S. Giscombe shares a resonant scene from his subconscious in the reverie of “Second Dream”; Timmy Straw recalls losing themselves in a yellowing issue of National Geographic, with a nod to Elizabeth Bishop’s “In the Waiting Room”; and in “My Blockchain,” Peter Mishler walks offstage with a literary mic drop par excellence.

Wallace Stevens once envisioned an ideal poet who coldly beholds “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” In this issue, you’ll find a poet who rewrites Wallace’s “The Snow Man” in her meditation “That Is”:

our thoughts

become the trying that is

trying to become

the yes that is

trying to unify us

into the nothing that is

Hannah Emerson’s insistent enjambments—from “the trying that is” to “the yes that is” to “the nothing that is”—convey us, and the snow men within, toward a breathtaking destination: “the freedom / that is / free of life yes yes.”

I’d like to conclude this holiday message with an invitation. Thanks to our stalwart crew of readers and editors, we’ll be throwing open our virtual doors more regularly to poetry submissions moving forward, with a Submittable reading period scheduled for January 2023. I can think of no better way to begin the new year—with a copy of our Winter issue in my parka pocket, new poems to read on my desk, and that singular feeling of “yes yes.”

Srikanth “Chicu” Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Review.

Letter from the Review’s New Poetry Editor

As a new member of the Review’s team, it gives me great pleasure to bring you several equally new contributors in our new Winter issue. Some are celebrated literary artists, some are emerging voices, and others fall somewhere in between. Perhaps the most lofty among them is William of Aquitaine, also known as the Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony and the Count of Poitou—the earliest troubadour whose work survives today. For all his lands and eleventh-century titles, there’s a slapstick vibe to this unwitting contributor’s bio that I can’t help but find endearing. Excommunicated not once but twice, and flagrant in his affairs and intrigues, William survived more ups and downs than most modern politicians could ever pull off, and in Lisa Robertson’s agile translation, he speaks to us from the end of his earthly tether: “I, William, have world-fatigue,” he sighs across the centuries.

Much of my new job involves sifting through the slush pile for unexpected gifts—so you can imagine how tickled I was to see the world-weary troubadour dust himself off once again in another poem, by Luis Alberto de Cuenca, titled “William of Aquitaine Returns,” translated into a measured and colloquial English by Gustavo Pérez Firmat:

I’m going to make a poem out of nothing.

You and I will be the protagonists.

Our emptiness, our loneliness,

the deadly boredom, the daily defeats.

The legendary Tang Dynasty poet Tu fu also makes a debut of sorts, in an extended excerpt from Eliot Weinberger’s forthcoming “The Life of Tu Fu,” the “fictional autobiography” of a poet who witnessed the violence, famine, and displacements of civil war in eighth-century China. “Is there anyone left, under a leaking roof, looking out the door?” the poet asks. “They even killed the chickens and the dogs.” Weinberger’s wry, oracular Tu Fu describes a world that feels painfully familiar; it might be Ethiopia, Myanmar, or any number of modern conflict zones.

Elsewhere in our pages, the Ukrainian-American poet Oksana Maksymchuk sends an update from her own war zone, awaiting an enemy’s barrage of propaganda in a cellar lined with strawberry jam; from the couch, C. S. Giscombe shares a resonant scene from his subconscious in the reverie of “Second Dream”; Timmy Straw recalls losing themselves in a yellowing issue of National Geographic, with a nod to Elizabeth Bishop’s “In the Waiting Room”; and in “My Blockchain,” Peter Mishler walks offstage with a literary mic drop par excellence.

Wallace Stevens once envisioned an ideal poet who coldly beholds “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” In this issue, you’ll find a poet who rewrites Wallace’s “The Snow Man” in her meditation “That Is”:

our thoughts

become the trying that is

trying to become

the yes that is

trying to unify us

into the nothing that is

Hannah Emerson’s insistent enjambments—from “the trying that is” to “the yes that is” to “the nothing that is”—convey us, and the snow men within, toward a breathtaking destination: “the freedom / that is / free of life yes yes.”

I’d like to conclude this holiday message with an invitation. Thanks to our stalwart crew of readers and editors, we’ll be throwing open our virtual doors more regularly to poetry submissions moving forward, with a Submittable reading period scheduled for January 2023. I can think of no better way to begin the new year—with a copy of our Winter issue in my parka pocket, new poems to read on my desk, and that singular feeling of “yes yes.”

Srikanth “Chicu” Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Review.

December 9, 2022

At Proust Weekend: The Madeleine Event

Over the course of Villa Albertine’s Proust Weekend, a series of talks, workshops, and readings celebrating the forthcoming English translation of the last volume of the Recherche and the centenary of Proust’s death, I ate more cakes per diem than usual: on Sunday afternoon, a miniature pistachio financier, a Lego-shaped and moss-textured cake that reminded me of the enormous chartreuse muffins at my college cafeteria; on Saturday morning, a crisp, disc-like, almond-sliver-sprinkled shortbread cookie with a hole, which reminded me of a Chinese coin; and, on Friday night, at a holiday party, a dish of Reddi-wip and sour cream studded with canned mandarin slices and maraschino cherries apparently called ambrosia salad. It reminded me of the music video for Katy Perry’s “California Gurls.” But these were really only preliminary research exercises for the episode in which Proust Weekend was to culminate: a “Proust-inspired madeleine event with surprise guests”!

In the meantime, I attended some panels. When Lydia Davis was beamed in to talk about her award-winning translation of Swann’s Way, I stared at the cat in the lower left-hand corner of the screen. In order to be properly Proustian, I knew, the center of an experience would be hidden in the margins of the event itself. The events of the Weekend transpired in the second-floor ballroom of the Gilded Age mansion that houses Villa Albertine, the French embassy–adjacent artist’s residency program that had organized the event. Most attendees were, I gathered, elderly residents of the Upper East Side and/or miscellaneous French people. The Payne Whitney Mansion seemed like a memory palace designed expressly for the contents of the Recherche: ceilings bordered by Rococo botanical motifs as rhizomatic as Proust’s syntax; or a purple-carpeted grand staircase bookended by two urns of exotic flora that reminded me of Combray’s psychedelically hued asparagus (“steeped in ultramarine and pink, whose tips, delicately painted with little strokes of mauve and azure, shade off imperceptibly down to their feet”).

On Sunday at four, Proust Weekenders would be getting an exclusive “first taste” of a special collaboration between Villa Albertine and the Ladurée pastry franchise: a madeleine-flavored macaron. I’m not sure why macarons were chosen instead of madeleines—perhaps because “macarons,” according to the president of Ladurée US, Elisabeth Holder, “are the supermodels of the food industry.” As I took my seat in the ballroom, I recalled all the Ladurée products I had consumed in the past year: most recently, rose petals suspended in a luminous pink jelly, on my birthday, which is also the date of Proust’s death; a turquoise macaron that I selected from a box of six others because I knew it was called the “Marie Antoinette”; half of the “Champs-Élysées Breakfast” served at Ladurée Soho (disgusting); approximately ten or twelve macarons of various colors, at an event for which I signed an NDA on an iPad at the door; and, last winter, an orange-colored macaron with a tiger printed on it. This last macaron, a Lunar New Year limited edition of some Asian flavor (mango? passion fruit?), gave me pause. Whenever I go into a Ladurée, the store is filled with Asian girls making their Asian boyfriends take pictures of them with their macarons—just like me. The franchise called Paris Baguette is actually Korean. The most recognizably Japanese fashions are strange perversions of those once worn at Versailles. Why do Asian girls love French things/sweets so much? I wondered, not for the first time.

Meanwhile, the madeleine event had begun. And the Villa Albertine had a surprise for us: there would be not one but three madeleine reinterpretations to be tasted tonight! We clapped and cheered. We were hungry. The interpretations sat on a small table at the front of the ballroom, arrayed in order of height. Behind them sat three French pastry chefs.

Pastries, it seems to me, are the perfect food for interpretation. Their distinct exterior shapes and conventionally determined flavors provide a set of coded forms ready-made for culinary rereadings: like the deconstructionist Dominique Ansel’s “cookie shot,” milk poured into a vessel made out of cookie. I think people love variations on a classic because they like to perceive forms and contents being playfully recombined on the normally nonliterate medium of their tongue, remixing their memories to psychedelic effect. (In East Asia, novelty reinterpretations of Western sweet foods, like wasabi-flavored Oreos, are peculiarly popular.) Fancier pastries are often adorned with quirky semiotic flourishes, in which ingredients inside the pastry are present in quasi-symbolic form outside of it, like candied tea leaves topping a tea-flavored tea cake. The madeleine, though, is a humble cookie made from brioche dough and shaped like a shell. It is basically birthday cake–flavored, which, when it comes to cakes, is like having no flavor at all. So I was skeptical of Ladurée’s madeleine-flavored macaron: was the soft madeleine, like the crisp macaron, not defined primarily by its texture? Was a madeleine-flavored macaron not oxymoronic, like a lemon-flavored orange? (It would have been more Proustian and Modernist, I thought, to make a madeleine in the shape of a paving stone, using, somehow, molecular gastronomy.)

Before we could taste these treats, another panel. The interpretations were explained to us. Chef Sebastien Rouxel, from the team at Daniel Boulud, had added Grand Marnier to the basic madeleine recipe and made a large loaf version of the cake. Chef Eunji Lee, who recently opened her own patisserie, Lysée, created a medium-size madeleine with a soft caramel center and a toasted brown rice glaze, in honor of her French Korean identity. And Chef Jimmy Leclerc, from Ladurée—the tallest of the three but the creator of the smallest pastry—was there to represent the madeleine-flavored macaron. The three chefs told us memories from their childhoods. Then they told us even more stories from their lives, which included transcontinental immigrations, detours into military service, and patisserie apprenticeships much more difficult than either of these. Questions were asked, jokes were made, and, at last, we were released into the Marble Room, where, meanwhile, three silver platters bearing Leclerc’s and Lee’s inventions, plus three silver urns dispensing hot drinks, had appeared on the Villa’s ivory tablecloths. (Rouxel’s loaf we would receive to go, as a party favor to share with loved ones.) I gathered my treats on a Ladurée logo’d napkin.

I put each one in my mouth one by one. The “hot” chocolate, though promisingly thick and sweet, was actually cold, like NyQuil. The unlabeled herbal tea tasted what I can only describe as “herbal.” Lee’s madeleine tasted like “yellow cake.” Ladurée’s madeleine-flavored macaron tasted more like a macaron than any macaron I’d ever had: crunchy and then soft, its center like butter mixed with sugar. Though I enjoyed each of these moments of the madeleine event, I did not have an experience of form, content, Proust, life, or literature—or really of anything, aside from pure sugar. Had I, in my research, eaten so many sweets in the past forty-eight hours that I was anesthetized to their reverie-inducing qualities?

I was about to get back in the now-dwindling pastry line for a second try when I was invited on a private tour of the mansion, which would end on the roof. Feeling vaguely sedated, as though the cocoa really had been NyQuil, I followed the dapper director of the Villa Albertine, plus the three chefs, up a long flight of stairs painted in a rainbow gradient of Ladurée macaron colors—Pistache, Citron, Rose, Cassis—until we emerged into the twilight above Fifth Avenue. The Midtown skyscrapers were all lit up for Christmas. Below us, the park was dark. The air was cold and bright. The sky was a color somewhere between Marie Antoinette and Cassis: it was beautiful. I gasped. So did the three chefs. The director took a TikTok (I think).

The wind whipped around me, I clambered over some kind of ventilation pipe, and I remembered, all of a sudden, Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep, in which Maggie Cheung, on Ambien and wearing a black latex catsuit, runs around at night on the roof of her Paris hotel. Cheung basically plays herself: a Hong Kong kung fu–flick actress who has been cast as the lead in a reinterpretation of a classic French film. It is the best acting I’ve ever seen: Cheung, who barely talks, manages to be both perfectly Oriental and something else behind that Oriental person that no one, on the screen or watching it, can really see. I remembered how, watching it, at sixteen, an age when I was “obsessed with Godard,” was the first time I really felt Chinese. And, as I shivered, because I was in fact attired in only a thin, cheetah-print catsuit, many of the details that had so randomly struck me over the course of that weekend, like Lydia Davis’s cat and Ladurée’s tiger flavor, reemerged and rearranged themselves, like the chemical transformations produced by cooking. I did not remember, until that moment, that when I, like Proust’s hero, have to go to bed earlier than my insomnia allows, I will smoke weed and listen to one of the five thirty-minute-long poetry readings by the Chinese American poet Tan Lin that I have downloaded to my phone. My favorite track is a poem in Seven Controlled Vocabularies in which Lin eats at a molecular gastronomy restaurant whose chef “is young and looks like a cowboy reincarnated as a skateboarder.” Why do Asian girls love French things/sweets so much? I do not know, but, until then, there on the roof, I had forgotten that I started this nightly listening practice when I was seeing someone trained as a French pastry chef who would sometimes, being a baker, leave my apartment before sunrise to work, waking me, and I realized that my taste for experimental poetry and therefore, indirectly, for Proust, was inextricably tied to desiring someone whose ambition was to make a psychoactive weed croissant, which is such a good idea. Language acts on you in surprising ways when you only hear it half-asleep. I realized that I had, over many nights, perfectly reproduced all of Seven Controlled Vocabularies somewhere in my memory. Cats feature in the book, as does being Chinese. I was grateful to Chef Eunji Lee, whose yellow-flavored psychoactive madeleine must have made me more Asian than I had previously realized. “The ideas of food erase the food itself and then become the food you did not think you were eating,” Lin said on the roof, in my head. “Off to one side of the fruit was smeared what looked like hot fudge sauce except that it was made of ketchup and jalapeno peppers. The sauce was semi-frozen. The sauce was hot and cold and cold and hot I couldn’t tell which. I put the pineapple in my mouth and it was like eating something that was once a vegetable.” I thought of wasabi-flavored Oreos, and M. Swann’s lover’s house full of Oriental flowers, which she loves for their “supreme merit of not looking in the least like other flowers, but of being made, apparently, out of scraps of silk or satin.” And as the sky above Central Park darkened, finally, to an inky color unknown to the kitchens at Ladurée, I had found the thought I had nearly forgotten, which is that I am really most Asian when I am asleep, or eating a macaron.

Olivia Kan-Sperling is an assistant editor at The Paris Review.

December 8, 2022

What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Goals?

The U.S.-Wales Men’s World Cup Match and Opening Ceremony in Doha, Qatar, on November 21, 2022. State Department photo by Ronny Przysucha, Public Domain.

Not long after Argentina lost in a stunning upset to Saudi Arabia and hardly anyone outside the losing country was crying, I read a new book, Dark Goals: How History’s Worst Tyrants Have Used and Abused the Game of Soccer, by the sports journalist Luciano Wernicke. Evita, I learned, once tried to fix a game between two Buenos Aires teams, Banfield and Racing, first by force of will and, when that failed, by offering a bribe to Racing’s goalkeeper: he could become mayor of his hometown. Of course, that kind of behavior is behind us (FIFA? Bribes? Are you kidding?), although government pressure and reward still hover on soccer’s periphery: Emmanuel Macron famously called Kylian Mbappé the best player in the current tournament, and urged him not to move from Paris Saint-Germain to Real Madrid, because, he said, “France needs you.” After the Saudi victory, a national holiday was declared in the oil-rich kingdom, all amusement parks were free, and citizens could enjoy their favorite rides for as long as they wished. In Qatar, outside interference of another kind was exposed when it came to light that those bouncing, joyful, muscle-bound, tattooed Qatar supporters in identical maroon T-shirts were actually faux fans imported from Lebanon and elsewhere, all-expenses-paid. They had been trained in patriotic Qatari chants. Meanwhile, the Ghana Football Association appealed to a higher power and urged two days of fasting and prayer nationwide to give its team the necessary boost. This sounds quite reasonable; there’s been an awful lot of skyward finger-pointing and prostrations of thanks by players after they score a goal. Someone’s deity is clearly playing a part. No one, to be clear, ever thanks God for a loss.

I’m going to abandon religion but stay on politics a little bit longer before we get to Richarlison’s stupendous scissor kick against Serbia, his matchless wonder goal against South Korea, and the rest of o jogo bonito. Early in the tournament seven European teams decided their captains would wear rainbow armbands in support of diversity and inclusion. This planned gesture of goodwill upset FIFA so much that it threatened to give out one yellow card per armband, which would certainly tip the balance unfavorably against teams whose players insisted on visibly supporting kindness, tolerance, and equality. The captains abandoned ship, but the Germans puckishly posed for a team picture with their hands over their mouths.

Speaking of which, a debate over nomenclature has emerged in the English-speaking part of the World Cup. During the U.S.A. v. England game, U.S. fans taunted their English counterparts by cheering, “It’s called SOCCER”—a witless banality that nevertheless has inspired and morphed into a popular Doritos ad in which Peyton Manning schools David Beckham. Or did the ad come first? The young, athletic U.S. team played really well; Christian Pulisic took his first steps toward sainthood; and the team drew but thoroughly deserved to win against a drab, pedestrian, unimaginative England. I was reminded of the time I saw the U.S.A. beat England 2–1 in a friendly at Foxboro Stadium a year before the 1994 World Cup. Toward the end of the game the small contingent of England fans began to chant, “We’re such shit it’s unbelievable.”

The commentary has been as sensational as you might imagine: In the first ten minutes of the showcase opening game between Qatar and Ecuador, Fox Sports lead play-by-play announcer, John Strong, noting that “this was a fistfight to start,” excitedly advised, “The ref must keep some sort of lid on this thing” when nothing remotely untoward had happened at all. The message was clear: Don’t worry, America, this sport is as down and dirty as a UFC cage fight! Fox Sports has also, unsurprisingly, sugarcoated the tournament and tried its best to ignore the politics, with little to no mention of the human rights issues and has elided, for example, the celebratory upheaval in the immigrant-heavy banlieues of Brussels after Morocco beat Belgium. In other parts of the world, the politics often come before the football. Even the British tabloid the Sun has sometimes foregrounded ugly issues, like the NO SURRENDER flag draped in the Serbian dressing room as an insult to Kosovo.