The Paris Review's Blog, page 59

April 4, 2023

Full-Length Mirror

Mirror piece, 1965. Art & Language. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 4.0.

My thirty-fourth year was meant to be a winner. I would drink less, I would eat better, I would write my book proposal, I would walk ten miles every day, I would go to the theater, I would get a job, I would read more books and watch more movies. I would, in short, live up to my potential. All my life I’ve seen out of the corner of my eye the other me, the one who rises early, sleeps well, spends responsibly, works hard, shines with a humble yet unmistakable brilliance, and never lets anybody down, the bitch. Well, no longer.

Thirty-three! Otherwise known as the Jesus year: thirty-three being the very age Jesus Christ got his show on the road. If it was good enough for the Son of God, surely it was good enough for me. Being simply human I didn’t expect a dove from heaven—just a little self-actualization, a shimmer of success, a whiff of recognition. Nothing big. In retrospect, it might have been better to dwell on the how of Jesus reaching his potential (i.e., death) and not so much the when. But I didn’t, and it wouldn’t have made a difference: almost precisely a month after reaching this momentous age, I was throwing up a yellow substance I didn’t like the look of into every available receptacle. Scripture is silent on whether this ever happened to Jesus, but since he participated in humanity in all its fullness, maybe it did.

***

My domestic situations have always had this problem: I buy things for the other me, who has great taste, but then I don’t know what to do with them, because they’re not my things, they’re hers. Other me—McClay A, let’s call her Alice—likes delicate coffee serving sets that would turn the humdrum act of sipping coffee in the morning into a small, beautiful ritual; real me habitually buys cheap iced coffee before going to sleep, placing it on the nightstand for the morning. What happens to the coffee service? Who knows. I look at it and am as charmed as ever. I’d buy it again, I’m sure.

And yet for a little over half a year this hasn’t been much of a problem. Not because Alice and I have harmonized but because my vomiting spell landed me in the hospital for two weeks, before I was discharged in a state so weak I could not walk to the corner of my block. I couldn’t feed myself and working was impossible. So I bowed to my fate and to my bank account, moved in with my parents, and went to the hospital two more times over the next few months as one of my organs necrotized. (It goes without saying, but these things never happen to Alice.) Unable to do anything, I listened over the phone as my long-suffering mother and boyfriend took care of all the things in my apartment one way or another. “You did kind of die,” he mused to me later, reflecting on his experience of disposing of my possessions. “I mean, it had a certain kind of resemblance.” I don’t know where these things went—some went into storage, I’ve been told, but the rest is just gone. Are the remainder my things, or are they Alice’s? Who knows—not me.

I cannot fill the home of other people with my own delusions. Not even if these other people are my parents. I can wishlist as many cunning little coffee contraptions as I desire, but there is no reason to buy them, no place to put them, and not even a little bit of a belief I would have any reason to use them. But being sick is, above all else, incredibly boring, and so it’s not surprising that I developed fixations. When I was actually in the hospital these fixations ran along practical lines: I would like not to be in pain, I would like to get out of here, I would like to take a shower, and so on. Out of the hospital, however, I had to pick something else. It couldn’t be furniture, cookware, or dishes. It couldn’t be anything that required me to do anything, like watercolors or yoga. So it was clothes.

With clothes, there’s always the trouble of what you want to wear and what you’ll actually wear. An office-appropriate and quite flattering sheath dress hangs in my closet but has little place in my officeless life. I bought it as if to say, It won’t always be this way. It’s still that way, but nevertheless, I research swimsuits late into the night . I haven’t been to the beach in years and the swimsuit I eventually settle on is ridiculously expensive, too expensive to impulse-buy. Once a week or so I go to the website and make sure it’s still there. It represents—what? The possibility of a carefree future, I suppose.

Brightly colored shoes, too, give me trouble. I feel, when I wear them, like a very delusional prey animal, bringing myself to the attention of every lion on the savannah. I do not fear real human predators, mind you, just bad luck. Long ago I remember reading a dubious study about shoe color, the findings of which were that people who wore predominantly black and brown shoes tended to have avoidant personalities, and taking stock of my black and brown shoes with resignation. What can you do? So I order sweaters and dresses that I’ll actually wear while lying around, and feel a little nicer lying around, and it works out rather well, most of the time.

And while the purchase of these clothes is motivated a hundred percent by personal vanity, they are plausibly practical: most of my old clothes are gone, and many no longer fit. You’ll always wear clothes. Still—there’s an issue.

***

How do you know how you look? You look in a mirror. Well, I have a mirror—one that shows my reflection from the waist up. But a full-length mirror—the kind that lets you really see how your clothes look—a useful thing to have, if your world has narrowed down to clothes—this, I do not have. Nor can I solve this dilemma by copping to my vanity and sneaking shame-faced, as I did as a teen, into my parents’ bathroom. They don’t have one now either. There isn’t one in the house. This is not, I should say, because of some ideological opposition to mirrors; my neuroticism about mirrors is entirely mine. There are plenty of mirrors. But there aren’t any built into this house, into which they recently moved, and they don’t feel the lack terribly much.

In my old life, full-length mirrors were not a problem, because people were always leaving them on the curb. Even when I smashed a mirror—you should believe all the stories about the consequences thereof, by the way—I found another one on the street just days later. But now, if I want a full-length mirror, I have to pay some amount of cold hard American cash for it. That is to say, I have to admit I want a mirror, which means admitting I want to look at my reflection in a mirror, and I have to go to the trouble of selecting a mirror to suit my needs (or wants, I suppose).

Like all vain people, I have a horror of seeming vain. And my vanity is the real thing. When people dab their faces with concealer, put on makeup, get some Botox, or thread their eyebrows, they’re confessing to a certain kind of humility. They could do with a little assistance, they’re saying. They’re making concessions. They do not think they are perfect just the way they are. But I don’t do any of this—I go about barefaced and let my eyebrows stay furry, not out of indifference, but because I like my face. That’s real vanity. It’s a misunderstood vice. So I am too vain, in fact, to admit that what I really want is not to check how I look, but just to look at myself; for my actual purposes, the bathroom mirror works perfectly well, particularly since I am rarely able to leave the house and thus never wear shoes.

A full-length mirror! Sometimes I think: No, I won’t pretend to be better than I am, I’ll take the plunge. I click around and add the cheapest one to my shopping cart. Then I see the future unfold before me: after an expenditure that would live in my records forever, I’d have to wait for it to arrive in the mail. Day by day I’d check its status. I’d worry that it would break. Upon its arrival, I’d probably need help maneuvering the package. To the inevitable comment that I’d purchased something large, I’d have to confess—yes, I have. A mirror. You know, in addition to the one I already have.

Oh, a mirror? says my interlocutor, who is no longer anybody I know but simply myself—not Alice but another self. This one’s a prosecutor; her name’s Simone. People are dying and you’ve bought a mirror? You could have given that money to a street urchin, but you bought a mirror? Standing on a chair to get a better look at yourself is just too hard for little old you, eh? Well, don’t let me interfere with your mirror. By the way, who made that mirror? Were you too cheap to get anything made in halfway decent labor conditions?

Click click click—the mirror comes out of the shopping cart. I purchase a book instead. Or maybe a sweater. Or shoes.

Would Alice buy a full-length mirror? That’s the trouble—I don’t know. She’d have one, obviously, but acquired through some mysterious means, maybe from a beautiful antique wardrobe, already intact. Or maybe she would buy one and set it up in some open area, smiling: “Darling, it’s simply courtesy to others just to give yourself a once-over in the mirror.” If I knew she’d buy one, then it wouldn’t be so fraught. My better self did it, so I will too.

A full-length mirror! What if I purchased one simply to prove that I didn’t have to look in it? It would be casually put in a corner, maybe with a sock hanging over it: Oh, a mirror? Yes, I suppose. I really forget it’s there, you know, I never use it. (My audience, sotto voce: And yet she’s always so well-dressed. And so brave!) With the mirror resolutely ignored, I would refine my vanity into something so much a vice as to be almost a virtue.

One thing’s for sure: if I had one, no matter what I did, it would bring everything to a resolution. I’d stop buying clothes. I would heal to become a better, stronger person than I was before I got sick. I’d never go back into the hospital. I would not require other people to pack up my apartment for me. I would write my book proposal, I would walk ten miles every day, I would go to the theater, I would get a job, I would read more books and watch more movies, I would rise early and sleep well, I would shine with a humble yet unmistakable brilliance, and I would never let anybody down.

A full-length mirror! Suppose one did simply appear—a good mirror, generous. I would look at the woman looking back at me. Who would be me, who would be Alice—it would be an irrelevant problem, because in that moment, as she blinks and I blink, as our mouths curve together in identical smiles, we would be at peace, the real disappointment and the unreal paradigm. Deep, deep we’d go, Alice and I, until we’d emerge in some other world, a perfect and complete being at last.

B.D. McClay is an essayist and critic. She has written for Lapham’s Quarterly, the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and other publications.

April 3, 2023

On Mary Wollstonecraft

Detail from John Opie’s portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft, 1790–1. Public domain.

Around the time I realized I didn’t want to be married anymore, I started visiting Mary Wollstonecraft’s grave. I’d known it was there, behind King’s Cross railway station, for at least a decade. I had read her protofeminist tract from 1792, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, at university, and I knew Saint Pancras Churchyard was where Wollstonecraft’s daughter, also Mary, had taken the married poet Percy Bysshe Shelley when they were falling in love. When I thought about the place, I thought of death and sex and possibility. I first visited at thirty-four, newly separated, on a cold gray day with a lover, daffodils rising around the squat cubic pillar. “MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT GODWIN,” the stone reads. “Author of A Vindication of the rights of Woman. Born 27th April, 1759. Died 10th September, 1797.” I didn’t tell him why I wanted to go there; I had a sense that Wollstonecraft would understand, and I often felt so lost that I didn’t want to talk to real people, people I wanted to love me rather than pity me, people I didn’t want to scare. I was often scared. I was frequently surprised by my emotions, by the things I suddenly needed to do or say that surged up out of nowhere.

Unexpected events had brought me graveside: when I was thirty-two, my fifty-seven-year-old mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. It wasn’t genetic; no one knew why she got it. We would, the doctors said, have three to nine more years with her. Everything wobbled. This knowledge raised questions against every part of my life: Was this worth it? And this? And this? I was heading for children in the suburbs with the husband I’d met at nineteen, but that life, the one that so many people want, I doubted was right for me. I was trying to find my way as a writer, but I was jumping from genre to genre, not working out what I most wanted to say, and not taking myself seriously enough to discover it, even. Who do you tell when you start to feel these things? Everything seemed immovable. Everything seemed impossible. And yet I knew I had to change my life.

There were a string of discussions with my husband, threading from morning argument to online chat to text to phone to therapy session to dinner, where we floated ideas about open marriage and relationship breaks and moving countries and changing careers and dirty weekends. But we couldn’t agree on what was important, and I began to peel my life away from his. We decided that we could see other people. We were as honest and kind and open as we could manage as we did this, which sometimes wasn’t much. The spring I began visiting Wollstonecraft’s grave, he moved out, dismantling our bed by taking the mattress and leaving me with the frame. I took off my wedding ring—a gold band with half a line of “Morning Song” by Sylvia Plath etched on the inside—and for weeks afterward, my thumb would involuntarily reach across my palm for the warm bright circle that had gone. I didn’t throw the ring into the long grass, like women do in the movies, but a feeling began bubbling up nevertheless, from my stomach to my throat: it could fling my arms out. I was free.

At first, I took my freedom as a seventeen-year-old might: hard and fast and negronied and wild. I was thirty-four and I wanted so much out of this new phase of my life: intense sexual attraction; soulmate-feeling love that would force my life into new shapes; work that felt joyous like play but meaningful like religion; friendships with women that were fusional and sisterly; talk with anyone and everyone about what was worth living for; books that felt like mountains to climb; attempts at writing fiction and poetry and memoir. I wanted to create a life I would be proud of, that I could stand behind. I didn’t want to be ten years down the wrong path before I discovered once more that it was wrong. While I was a girl, waiting for my life to begin, my mother gave me books: The Mill on the Floss when I was ill; Ballet Shoes when I demanded dance lessons; A Little Princess when I felt overlooked. How could I find the books I needed now? I had so many questions: Could you be a feminist and be in love? Did the search for independence mean I would never be at home with anyone, anywhere? Was domesticity a trap? What was worth living for if you lost faith in the traditional goals of a woman’s life? What was worth living for at all—what degree of unhappiness, lostness, chaos was bearable? Could I even do this without my mother beside me? Or approach any of these questions if she was already fading from my life? And if I wanted to write about all this, how could I do it? What forms would I need? What genre could I be most truthful in? How would this not be seen as a problem of privilege, a childish demand for definition, narcissistic self-involvement, when the world was burning? Wouldn’t I be better off giving away all I have and putting down my books, my movies, my headphones, and my pen? When would I get sick of myself?

The questions felt urgent as well as overwhelming. At times I couldn’t face the page—printed or blank—at all. I needed to remind myself that starting out on my own again halfway through life is possible, has been possible for others—and that this sort of life can have beauty in it. And so I went back to the writers I’d loved when I was younger—the poetry of Sylvia Plath, the thought of Simone de Beauvoir and Mary Wollstonecraft, the novels of Virginia Woolf and George Eliot. I read other writers—Elena Ferrante, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison—for the first time. I watched them try to answer some of the questions I myself had. This book bears the traces of the struggles they had, as well as my own—and some of the things we all found that help. Not all of the solutions they (and I) found worked, and even when they did, they didn’t work all the time: if I’d thought life was a puzzle I could solve once and for all when I was younger, I couldn’t believe that any longer. But the answers might come in time if I could only stay with the questions, as the lover who came with me to Wollstonecraft’s grave would keep reminding me.

***

A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it.

On my first reading of A Vindication as a twenty-year-old undergraduate, I looked up the antique words and wrote down their definitions (to vindicate was to “argue by evidence or argument”). I followed Wollstonecraft’s arguments in favor of education. I knew she’d been a teacher, and saw how reasonable her main argument was: you had to educate women, because they have influence as mothers over infant men. I took these notes eighteen months into an undergraduate degree in English and French in the library of an Oxford college that had only begun admitting women twenty-one years before. I’d arrived from an ordinary school, had scraped by in my first-year exams, and barely felt I belonged. The idea that I could think of myself as an intellectual as Mary did was laughable. Yet halfway into my second year, I discovered early women’s writing. I was amazed that there was so much of it—by protonovelists such as Eliza Haywood, aristocratic poets like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and precursors of the Romantics like Anna Laetitia Barbauld—and I was angry, often, at the way they’d been forgotten, or, even worse, pushed out of the canon. Wollstonecraft stood out, as she’d never been forgotten, was patently unforgettable. I longed to keep up with her, even if I had to do it with the shorter OED at my elbow. I didn’t see myself in her at the time. It wasn’t clear to me when I was younger how hard she had pushed herself.

Later in her life, Wollstonecraft would defend her unlettered style to her more lettered husband:

I am compelled to think that there is something in my writings more valuable, than in the productions of some people on whom you bestow warm elogiums—I mean more mind—denominate it as you will—more of the observations of my own senses, more of the combining of my own imagination—the effusions of my own feelings and passions than the cold workings of the brain on the materials procured by the senses and imagination of other writers—

I wish I had been able to marshal these types of arguments while I was at university. I remember one miserable lesson about Racine, just me and a male student who’d been to Eton. I was baffled by the tutor’s questions. We would notice some sort of pattern or effect in the lines of verse—a character saying “Ô désespoir! Ô crime! Ô déplorable race!”—and the tutor would ask us what that effect was called. Silence. And then the other student would speak up. “Anaphora,” he’d say. “Chiasmus. Zeugma.” I had no idea what he was talking about; I’d never heard these words before. I was relieved when the hour was over. When I asked him afterward how he knew those terms, he said he’d been given a handout at school and he invited me to his room so that I could borrow it and make a photocopy. I must still have it somewhere. I remember feeling a tinge of anger—I could see the patterns in Racine’s verse, I just didn’t know what they were called—but mostly I felt ashamed. I learned the terms on the photocopy by heart.

Mary knew instinctively that what she offered was something more than technical accuracy, an unshakeable structure, or an even tone. Godwin eventually saw this too. “When tried by the hoary and long-established laws of literary composition, [A Vindication of the Rights of Woman] can scarcely maintain its claim to be placed in the first class of human productions,” he wrote after her death. “But when we consider the importance of its doctrines, and the eminence of genius it displays, it seems not very improbable that it will be read as long as the English language endures.” Reading it again, older now, and having read many more of the feminist books that Wollstonecraft’s short one is the ancient foremother of, I can see what he means.

There are funny autobiographical sketches, as where Mary is having a moment of sublimity at a too-gorgeous sunset only to be interrupted by a fashionable lady asking for her gown to be admired. There is indelible phrasemaking, such as the moment when Mary counters the Margaret Thatcher fallacy—the idea that a woman in power is good in itself—by saying that “it is not empire, but equality” that women should contend for. She asked for things that are commonplace now but were unusual then: for women to be MPs, for girls and boys to be educated together, for friendship to be seen as the source and foundation of romantic love. She linked the way women were understood as property under patriarchy to the way enslaved people were treated, and demanded the abolition of both systems. She was also responding to an indisputably world-historical moment, with all the passion and hurry that that implies. Specifically, she addressed Talleyrand, who had written a pamphlet in support of women’s education, but generally, she applied herself to the ideas about women’s status and worth coming out of the brand-new French republic. In 1791, France gave equal rights to Black citizens, made nonreligious marriage and divorce possible, and emancipated the Jews. What would England give its women? (Wollstonecraft was right that the moment couldn’t wait: Olympe de Gouges, who wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in October 1791 and ironically dedicated it to Marie-Antoinette, was guillotined within two years of its publication.)

And though I love the Vindication for its eccentricities, I also love it for its philosophy. It is philosophically substantial, even two centuries later. Wollstonecraft understood how political the personal was, and that between people was where the revolution of manners she called for could be effected. “A man has been termed a microcosm,” she writes, “and every family might also be called a state.” The implications of this deceptively simple idea would echo down the centuries: what role should a woman occupy at home, and how does that affect what she is encouraged to do in the wider world? Every woman in this book struggles with that idea, from Plath’s worry that becoming a mother would mean she could no longer write poetry to Woolf’s insecurity about her education coming from her father’s library rather than from an ancient university. Much of Wollstonecraft’s own thought had risen from her close reading of Rousseau, particularly from her engagement with Émile, his working-through of an ideal Enlightenment education for a boy. I didn’t find as an undergraduate, and still don’t, her argument for women’s education, which is that women should be educated in order to be better wives and mothers, or in order to be able to cope when men leave them, to be feminist. But now I can see that Wollstonecraft was one of the first to make the point that feminists have repeated in various formulations for two hundred years—though I hope not forever. If woman “has reason,” Mary says, then “she was not created merely to be the solace of man.” And so it follows that “the sexual should not destroy the human character.” That is to say, that women should above all be thought human, not other.

***

With so much of Wollstonecraft’s attention taken up by revolutionary France, perhaps it was inevitable that she would go there. She wrote to Everina that she and Johnson, along with Fuseli and his wife, were planning a six-week trip: “I shall be introduced to many people, my book has been translated and praised in some popular prints; and Fuseli, of course, is well known.” She didn’t say that she had fallen in love with Fuseli. The painter was forty-seven and the protofeminist twenty-nine. Mary hadn’t been without admirers—she met a clergyman she liked on the boat to Ireland; an MP who visited Lord Kingsborough seemed taken with her too—but marriage didn’t appeal. She joked with Roscoe (not just a fan but another admirer, surely) that she could get married in Paris, then get divorced when her “truant heart” demanded it: “I am still a Spinster on the wing.” But to Fuseli, she wrote that she’d never met anyone who had his “grandeur of soul,” a grandeur she thought essential to her happiness, and she was scared of falling “a sacrifice to a passion which may have a mixture of dross in it … If I thought my passion criminal, I would conquer it, or die in the attempt.” Mary suggested she live in a ménage à trois with Fuseli and his wife. He turned the idea down, the plan to go to Paris dissolved, and Mary left London on her own.

She arrived in the Marais in December 1792, when Louis XVI was on trial for high treason. On the morning he would mount his defense, the king “passed by my window,” Mary wrote to Johnson. “I can scarcely tell you why, but an association of ideas made the tears flow insensibly from my eyes, when I saw Louis sitting with more dignity than I expected from his character, in a hackney coach, going to meet death.” Mary was spooked: she wished for the cat she had left in London, and couldn’t blow out her candle that night. The easy radicalism she had adopted in England came under pressure. Though she waited until her French was better before calling on Francophone contacts, she began to meet other expatriates in Paris, such as Helen Maria Williams, the British poet Wordsworth would praise. In spring 1793, she was invited to the house of Thomas Christie, a Scottish essayist who had cofounded the Analytical Review with Johnson. There she met Gilbert Imlay, an American, and fell deeply in love.

Imlay was born in New Jersey and had fought in the War of Independence; he was writing a novel, The Emigrants, and made money in Paris by acting as a go-between for Europeans who wanted to buy land in the U.S. and the Americans who wanted to sell it to them. It is as if all Mary’s intensity throughout her life so far—the letters to Jane Arden, her devotion to Fanny Blood, her passion for Fuseli—crests in her affair with this one man, whom she disliked on their first meeting and decided to avoid. Imlay said he thought marriage corrupt; he talked about the women he’d had affairs with; he described his travels through the rugged West of America. After the disappointment with Fuseli, she offered up her heart ecstatically, carelessly: “Whilst you love me,” Mary told him, making a man she’d known for months the architect and guardian of her happiness, “I cannot again fall into the miserable state, which rendered life a burthen almost too heavy to be borne.” And yet she also noticed she couldn’t make him stay: “Of late, we are always separating—Crack!—crack!—and away you go.”

When my husband and I agreed we could see other people, he created a Tinder profile, using a photo I’d taken of him against a clear blue sky on the balcony of one of our last apartments together. He wanted to fall in love again and have children: pretty quickly he found someone who wanted that too. I met someone at a party who intrigued me, another writer visiting from another city, and I began spending more time with him: in front of paintings, at Wollstonecraft’s grave, on long walks, at the movies, talking for hours in and out of bed. After being married for so long, it was strange and wonderful to fall in love again; I felt illuminated, sexually free, emotionally rich, intellectually alive. I liked myself again. But I fought my feelings for him, reasoning that it was too soon after my husband, that sentiments this strong were somehow wrong in themselves, that he would go back to his own city soon and so I must give him up no matter what I felt. When he was gone, though, I saw I had found that untameable thing, a mysterious recognition, everything the poets mean by love. I wrote him email after email, sending him thoughts and feelings and provocations, trying out ideas for my new life, which I hoped would include him. Sometimes I must have sounded like Wollstonecraft writing to Imlay.

Mary moved to Neuilly-sur-Seine, a leafy village on the edge of Paris, and began writing a history of the revolution; throughout that summer of 1793, she and Imlay would meet at the gates, les barrières, in the Paris city wall. (Bring your “barrier-face,” she would ask him when the affair began to turn cold, and she wanted to go back to the start.) “I do not want to be loved like a goddess; but I wish to be necessary to you,” she wrote. Perhaps there was something in her conception of herself that made her think she could handle a flirt like Imlay. “Women who have gone to great lengths to raise themselves above the ordinary level of their sex,” Mary’s biographer Claire Tomalin comments, “are likely to believe, for a while at any rate, that they will be loved the more ardently and faithfully for their pains.” Mary perhaps believed she was owed a great love, and Imlay was made to fit. “By tickling minnows,” as Virginia Woolf put it in a short essay about Wollstonecraft, Imlay “had hooked a dolphin.” By the end of the year, Mary was pregnant.

Françoise Imlay (always Fanny, after Fanny Blood) was born at Le Havre in May 1794, and Mary wrote home that “I feel great pleasure at being a mother,” and boasted that she hadn’t “clogged her soul by promising obedience” in marriage. Imlay stayed away a lot; in one letter, Mary tells him of tears coming to her eyes at picking up the carving knife to slice the meat herself, because it brought back memories of him being at home with her. As she becomes disillusioned by degrees with Imlay, whose letters don’t arrive as expected, she falls in love with their daughter. At three months, she talks of Fanny getting into her “heart and imagination”; at four months, she notices with pleasure that the baby “does not promise to be a beauty, but appears wonderfully intelligent”; at six months, she tells Imlay that though she loved being pregnant and breastfeeding (nursing your own child was radical in itself then), those sensations “do not deserve to be compared to the emotions I feel, when she stops to smile upon me, or laughs outright on meeting me unexpectedly in the street, or after a short absence.”

Imlay’s return keeps being delayed, and Wollstonecraft uses her intellect to protest, arguing against the commercial forces that keep him from “observing with me how her mind unfolds.” Isn’t the point, as Imlay once claimed, to live in the present moment? Hasn’t Mary already shown that she can earn enough by her writing to keep them? “Stay, for God’s sake,” she writes, “let me not be always vainly looking for you, till I grow sick at heart.” Still he does not come, and her letters reach a pitch of emotion when she starts to suspect he’s met someone else. “I do not choose to be a secondary object,” she spits. She already knew that men were “systematic tyrants.” “My head turns giddy, when I think that all the confidence I have had in the affection of others is come to this—I did not expect this blow from you.” She starts signing off each letter with the threat that it could be the last he receives from her.

In April 1795, she decided to join him in London if he would not come to her. “I have been so unhappy this winter,” Mary wrote. “I find it as difficult to acquire fresh hopes, as to regain tranquility.” Fanny was nearly a year old, and Imlay had set up home for them in Soho. She attempted to seduce him; he recoiled. (He had been seeing someone, an actress.) She took the losses—of her imagined domestic idyll, of requited love, of a fond father for her daughter—hard, and planned to take a huge dose of laudanum, which Imlay discovered just in time. I find it unbearable that Mary, like Plath, would think that dying is better for her own children than living, but neither Mary nor Sylvia were well when they thought that, I tell myself.

Imlay suggested that Mary go away for the summer—he had some business that needed attention in Scandinavia. A shipment of silver had gone missing, and he could do with someone going there in person to investigate. She could take Fanny, and a maid. The letters Mary wrote to him while waiting in Hull for good sailing weather show that she had not yet recovered: she looks at the sea “hardly daring to own to myself the secret wish, that it might become our tombs”; she is scared to sleep because Imlay appears in her dreams with “different casts of countenance”; she mocks the idea that she’ll revive at all. “Now I am going towards the north in search of sunbeams!—Will any ever warm this desolated heart? All nature seems to frown—or rather mourn with me.” But she had an infant on her hip, a business venture to rescue that might also bring back her errant lover, and from the letters she wrote home, she’d mold a book that would unwittingly create a future for herself, even when she was not entirely sure she wanted one.

An adapted excerpt of A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again, to be published by Ecco/HarperCollins this May.

Joanna Biggs is the author of All Day Long: A Portrait of Britain at Work and a senior editor at Harper’s Magazine. In 2017, she cofounded Silver Press, a feminist publishing house.

March 31, 2023

John Wick Marathon

Keanu Reeves as John Wick in John Wick: Chapter 4. Photograph by Murray Close. Courtesy of Lionsgate.

In our Spring issue, we published Kyra Wilder’s poem “John Wick Is So Tired.” To celebrate the poem and the recent release of John Wick: Chapter 4, we sent four reviewers to three different John Wick screenings over the course of a week.

Tuesday, March 21: Press Preview

The first thing we noted when we entered AMC Lincoln Square 13 for the New York press screening of John Wick: Chapter 4 was that film PR girls are way nicer than their fashion industry counterparts. Check-in was a breeze, and we were informed that since we had special blue wristbands, we didn’t have to turn in our phones. We hadn’t considered that we would potentially have to turn in our phones, but were relieved nevertheless. We were handed a very large stack of papers with a large John Wick logo at the top, containing detailed information about the franchise and a long explanation of the movie’s plot, which we chose not to read too closely for fear of spoilers. This heavy stack of papers was also where we first learned that the runtime was a whopping 169 minutes. This troubled us, mostly because we had had a lot of wine with dinner and were concerned that we would have to pee. The theater was packed with agitated-seeming nonjournalists who were somehow able to secure tickets. People wove up and down the aisles in a huff, frustrated by the first-come-first-served seating. A couple of women exchanged curse words over another woman’s volume. Multiple people arrived late with full take-out bags, their lack of discretion leading us to believe that the staff of the theater were not too concerned with enforcing the rules of this AMC John Wick press preview.

The French crime film maestro Jean-Pierre Melville once said, “What is friendship? It’s telephoning a friend at night to say, ‘Be a pal, get your gun, and come on over quickly.’ ” In the universe of John Wick, it’s pretty much that too, but it’s a thousand guns, two dozen archers, bows, arrows, knives, swords, bulletproof suits, a sundry list of exotic ammunition, an attack dog, a blind assassin, dueling pistols, a fleet of luxury attack vehicles, and a handful of classic American muscle cars. Oh, and if you could bring them all to the Sacré-Cœur, in Paris, by sunrise, that would be great, thanks.

By now, with the fourth installment in the franchise, the formula is familiar. John Wick (Keanu Reeves), on the run from the High Table (a governing body for the underworld whose main function just seems to be killing people) kills a lot of people in a series of highly choreographed set-piece action sequences in places like fancy hotels for assassins, fancy churches for assassins, and fancy Berlin techno clubs, also presumably for assassins. There’s something very charmingly mid-2010s about the environs and the soundtrack (was that the opening of Justice’s “Genesis”?), like a world where there was no COVID pandemic, but where everyone is a rich assassin in an ugly custom three-piece sparkly suit. Better times.

Reeves speaks softly and carries a number of big loud sticks, swords, et cetera, often breaking down his guns into their constituent parts and throwing them, stabbing people with them, or indulging in other creative but necessary acts of violence. There’s an extremely fetishistic aspect to the gearheaded breakdown of the guns, and to the clicking of magazine releases, that forms a sort of counterpoint to the theoretically balletic fight choreography. Like Jean-Pierre Melville, John Wick normally drives a classic Mustang. How a similar car made its way to Paris in this film is anyone’s guess. There really aren’t any other comparison points between this film and Melville’s Le Samouraï, except that they’re both about assassins. Oh, and friendship.

—Alex Tsebelis and Chloe Mackey

Thursday, March 23: Premiere Day

I was supposed to go to a cosplay premiere event for John Wick: Chapter 4, but couldn’t get tickets in time—so I ended up at a normal Regal theater for the nearly sold-out 7 P.M. screening. I’d dressed for cosplay that morning, but I’d also never seen a John Wick film, so I had to make some educated guesses. Action movies, I knew, are all about men in suits performing suit-inappropriate actions. Assuming John would have a sexy love interest (this turned out to be wrong), I selected the female suit equivalent, a secretary costume: fitted brown houndstooth minidress. I loitered at the Regal Essex Crossing second-floor bar, photographing my outfit against the sunset over the Williamsburg Bridge, a very John Wick backdrop. “Is this for a fashion blog?” the Regal bartender asked me, winking. “No,” I said. “I mean, yes.”

Everyone else in the audience wore joggers, a garment absent from the fashion-forward film. Indeed, without context, the opening sequence registered to me as a kind of psychedelically plotless Saint Laurent advertisement, a brand for which Keanu Reeves is an “ambassador.” We begin with John Wick punching a brick in an elaborately shadowy warehouse. His training is interrupted by the dramatic entrance of his three-piece suit, appearing, silhouetted against the inexplicably fiery glow of a doorway, in the hands of some sinister fellow (friend, foe, butler?). The suit—presented in a manner usually reserved for the hero’s weapon of choice—is accompanied by a line of dialogue I neither understood at the time nor remember now, but which was clearly a classic John Wick catchphrase that meant something like “Here’s your suit. Now it’s time to kill—again.” And he totally does.

Wick’s antagonist, the Marquis, sports a series of glittery waistcoats complete with asymmetrical gold buttons and stupid little chains. His weapon: blades. His goal: glory. The effete Marquis probably has ten times as much dialogue, and charisma, as John Wick, who is completely without character attributes. John Wick is just a killer, more like a machine than a human being. His suit, like his gun, is all-black.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

Tuesday, March 28

The statistically inclined among us might have told me, as my projectionist friend did later on, that the odds of the screen going black twenty minutes into my 10:30 A.M. Sunday-brunch screening of John Wick: Chapter 4 at the Alamo Drafthouse up at least three escalators in the City Point mall were actually not so low in the age of automated projection. So my associate (a different one) and I finished our cauliflower-crust breakfast pizza and got a refund, and I picked up where we’d left off two days later at AMC 34th Street 14, where Nicole Kidman’s on-screen avatar assured me that the display was IMAX and the projectors laser. In the basement of a Berlin techno club full of bad, identically robotic dancers making repetitive upward arm movements, John Wick is dealt in to a five-card-draw game of poker with the two hitmen contracted to murder him and a German High Table official named Killa. At the end of the game, Wick puts two black eights and two black aces on the table, in what is usually a strong move—called the dead man’s hand, as I learned that night on the Reddit forum r/NoStupidQuestions, after the hand Wild Bill Hickok was reputedly holding when he was shot—but Killa destroys his chances by playing an unbeatable five of a kind: impossible to achieve without cheating, of course, because there are only four suits in a deck. Vegas would do well to be reminded, though, of the words of the Marquis, which I should start telling myself when I wake up in the morning: “How you do anything is how you do everything.” The odds are always against John Wick, and he always wins anyway. In the end, he slices Killa’s neck open with a playing card, and pockets one of his gold teeth.

—Oriana Ullman, assistant editor

March 30, 2023

Stationery in Motion: Letters from Hotels

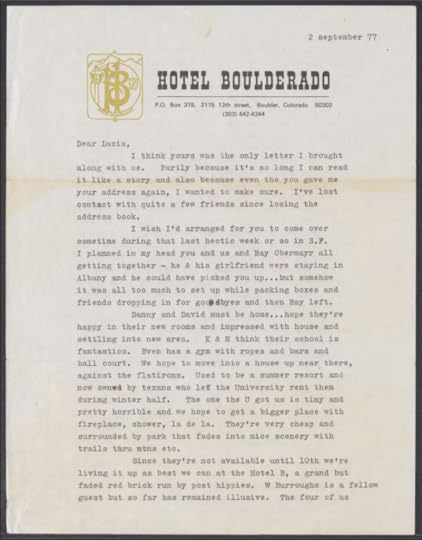

Jennifer Dunbar Dorn’s letter to Lucia Berlin from the Hotel Boulderado, September 2, 1977. Courtesy of Jennifer Dunbar Dorn and the Lucia Berlin Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In 1977, Jennifer Dunbar Dorn wrote to her best friend, Lucia Berlin, from the Hotel Boulderado, where she was staying while she looked for a house in Boulder, Colorado. Her “large corner room” became “a dormitory at night,” while “during the day we roll the beds into a cupboard in the hall.” She described the hotel as a “faded red brick run by post hippies,” a place for people on the make and on the move. This might not seem like a hotel that would have had its own stationery, but it did. The paper’s crest features a lantern and mountains, and the header reads HOTEL BOULDERADO in French Clarendon font: the typeface of Westerns and outlaws, of greed, gambling, and adventure. The hotel’s name, Dunbar Dorn recently pointed out to me, “is a combination of Boulder and Colorado, obviously, but the mythic El Dorado is ingrained everywhere in the West”—its lost city of gold.

I stumbled on this letter at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where a collection of Berlin’s papers are stored in a single cardboard box. Almost everything she saved over the course of her peripatetic life is compressed into this tiny space: correspondence, notebooks, reviews, manuscripts, applications for tenure. I am Berlin’s first biographer, and I often felt deeply moved as I worked through the box last summer. Berlin is my El Dorado, and I had been looking for her for so long … Though the archivists at the library had sent me scans of some of these documents during the pandemic, it wasn’t the same as touching pages she had once touched.

As I examined the yellowed paper, placing my own thumb over the smudged thumbprint at the top, I imagined Berlin reading Dunbar Dorn’s letter at her kitchen table in Oakland after a shift on the Merritt Hospital switchboard. Mostly, it’s about Dunbar Dorn’s journey from California to Colorado with her husband, Ed Dorn, and their children. Her emphasis is on their time on the road, not on their arrival—on transience over stasis and on quest over complacency, core values of the counterculture to which she, Dorn, Berlin, and their dispersed community of writers and artists loosely belonged.

A postcard from the Hotel Acapulco, from the fifties.

The Boulderado letter stood out to me because of the paper on which it was written. I got to Harvard in the third week of a research trip in pursuit of Berlin’s scattered correspondence, and along the way I’d become obsessed with hotel stationery. The appeal, at first, was aesthetic: hotel paper is pretty, and from the forties to the seventies, it was ubiquitous across the States and Europe. A few days earlier, while wading through the papers of Berlin’s literary agent, Henry Volkening, at the New York Public Library, I’d noticed that many of his clients wrote to him from hotels. Berlin herself first used her author name on a hotel postcard to Volkening in 1961. She had just eloped to Acapulco with her third husband, Buddy Berlin, and she described her newfound happiness, signing off: “Lucia Berlin.”

But many of the hotel letters I sought out had nothing to do with Berlin’s work. By my third or fourth archive—in my third or fourth American city—I was skipping lunch breaks to call up boxes belonging to writers who I knew traveled frequently: James Baldwin, Anaïs Nin, Raymond Chandler. Here is some of what I found.

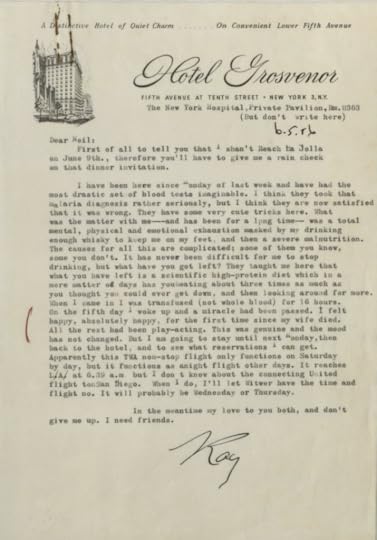

Raymond Chandler’s letter to Neil Morgan from the Hotel Grosvenor, June 5, 1956. © The Estate of Raymond Chandler. Courtesy of the Estate, c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

The Hotel Grosvenor

Raymond Chandler wrote to his friend Neil Morgan on Hotel Grosvenor paper in 1956, describing a recent bout of “mental, physical and emotional exhaustion” that he dealt with by “drinking enough whiskey to keep me on my feet.” At a second glance, the address on Fifth Avenue is underlined by a second one, of Room H363 at the private pavilion of New York Hospital (“But don’t write here”). Chandler wasn’t at the Grosvenor anymore; he was at the hospital, recovering from a breakdown. The hotel stationery was a respectable front for a man who had been institutionalized but who still wanted the people who loved him to know where he was. “Don’t give me up,” he ends the letter to Morgan. “I need friends.”

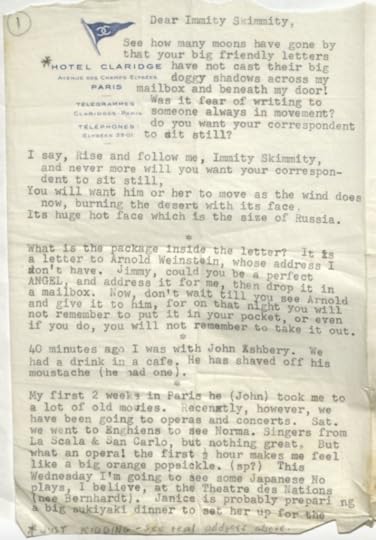

Kenneth Koch’s letter to James Schuyler from the Hotel Claridge, from the late fifties. Courtesy of the Kenneth Koch Estate and the James Schuyler Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego.

The Hotel Claridge

In the late fifties, Kenneth Koch sent James Schuyler a letter on paper from the Hotel Claridge in Paris, a Champs-Élysées institution and a rendezvous for “touristes fortunés,” Koch wonders whether “fear of writing to someone always in movement” is what has kept Schuyler from keeping in touch. He continues with a riff on the New Testament: “Rise and follow me, Immity Skimmity, and never more will you want your correspondent to sit still.” As it was for Berlin and the Dorns, a particular type of transience was, for Koch, a virtue. He traveled to escape the system, not to be coddled in upholstered rooms like the luxury suites at the Claridge. There is an asterisk next to the hotel crest: “Just kidding,” he adds, “see real address above.” This, it turns out, is 41, rue du Cherche-Midi, in the then hip and nonconformist sixth arrondissement, which, since the war, had become the headquarters of existentialism and bebop jazz. He must have swiped the Hotel Claridge stationery; his correspondence wears it as a costume to play a visual trick on Schuyler—to “kid.”

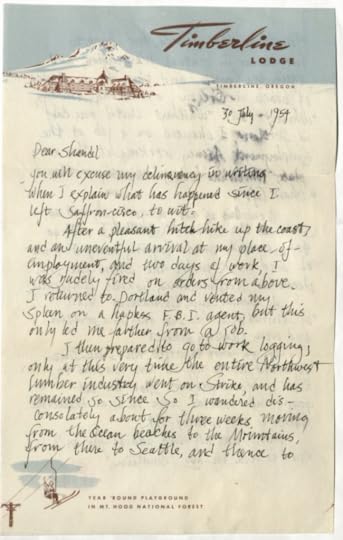

Gary Snyder’s letter to Shandel Parks from Timberline Lodge, July 30, 1954. Courtesy of Gary Snyder and the Gary Snyder Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.

Timberline Lodge

Hotel stationery leaves plenty of space for editorializing. Gary Snyder wrote to Shandel Parks in 1954 from Timberline Lodge in the Oregon mountains. The hotel’s name and outline appear on the header, and at the bottom of the page there is an illustration of a ski lift, with tiny letters reading YEAR ’ROUND PLAYGROUND IN MT. HOOD NATIONAL FOREST.

Snyder explains to Parks that he has been wandering “disconsolately about,” from “the ocean beaches to the Mountains, from there to Seattle, and thence to Mountains near Canada, and back to Mountains in central Washington, and again to Seattle, and then to a stretch of beach in central Washington, wondering, always, ‘Whence?’ and ‘Whither?’” Finally, he “chanced on a job” at Timberline Lodge, “attending to the «chair lift».” He did not plan to stay long. The double chevrons around “chair lift” are a different shape from the other quotation marks in his text, as though the language of chairlifts is not his own. At Timberline Lodge, Snyder was immersed in an unfamiliar, all-American world of commercialized leisure, one he mocks with his infantilizing caption. He kept its chairlifts running, while maintaining the detachment that pervades his letter to Parks. He makes clear that as soon as the lumber strike in the Pacific Northwest is settled, he “will go to a certain crude logging camp” and “work until the snow flies. i.e. December, accumulating hoards of money.”

Back to the Boulderado

By the time Dunbar Dorn wrote to Berlin in the late seventies, the Hotel Boulderado’s stationery was informed by a countercultural aesthetic that was beginning to enter the mainstream. The whimsical logo and typography suggest that the hotel catered to seekers, dissenters, and outlaws—or to people who saw themselves as such. Guests included William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Ishmael Reed, plus a rotating cast of speakers at the University of Colorado and the Naropa Institute. In his 1975 song “Come Back to Us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard,” John Prine describes a hippie “buying quaaludes on the phone … In the Hotel Boulderado / at the dark end of the hall.”

And yet the hotel remained, fundamentally, a business. In the eighties, after scraping together funds to renovate, it shed its dissident aesthetic and reverted to the plush accessories and prices with which it had opened in 1908. Today, rooms start at two hundred dollars a night, and the “happenings” advertised on the hotel website include a monthly “wine club” starting at forty dollars per person. Burroughs and rollaway beds are a distant memory.

When I called the Boulderado to ask if they still print their own stationery, the front-office manager told me that they did, but that she used it for official correspondence and welcome letters to guests. Branded paper is no longer placed in the rooms. And this brings something home: no matter how closely I follow Berlin, I can never truly enter her world, because it is gone, along with the golden age of hotel stationery. What endures, of course, is Berlin’s work. In her short story “Dr. H. A. Moynihan,” originally published under the title “The Legacy” in 1982, a dentist shows his granddaughter a set of false teeth. “He had changed only one tooth,” Berlin writes, “one in front that he had put a gold cap on. That’s what made it a work of art.” I think, for her, this was a metaphor for the creative process. She does something similar with her fiction, drawing on her experience and transforming it, too, as Lydia Davis has observed. And her interventions, innovations, additions, and omissions catch the light: they’re the treasures, like El Dorado, or the gold cap on a tooth.

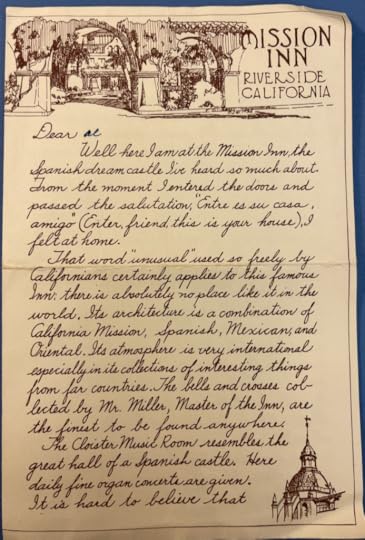

A prewritten hotel letter from the Mission Inn, March 14, 1946.

Nina Ellis is a British American writer and scholar. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Granta, The Idaho Review, The London Magazine, the Oxford Review of Books, and elsewhere. She won an Editors’ Choice Award in the 2021 Raymond Carver Short Story Contest. Looking for Lucia: A Biography will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2025.

Making of a Poem: Kyra Wilder on “John Wick Is So Tired”

Photograph courtesy of Kyra Wilder.

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Kyra Wilder’s “John Wick Is So Tired” appears in our new Spring issue, no. 243.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

With the first line. It was something I’d thought a lot about—I run marathons, and in those tense few days before the race, when I’m drinking water and carb loading and meditating on what’s going to happen, I watch John Wick, specifically because of the way Keanu Reeves runs. He looks so tired, but he’s winning.

In the fall of 2021, I was tapering for a marathon and then I had to go to a funeral, and suddenly my John Wick time got invaded by real grief. And John Wick was good for that, too.

What were you reading while you were writing the poem?

I was reading a lot of Ian Fleming that fall. I got pretty obsessed with the fact that he included a recipe for scrambled eggs in a James Bond story. In that story, Bond is completing some kind of mission in New York but also being really whiny about the poor quality of American eggs—to the point that he’s wandering around the city going into bodegas and criticizing them. So, it was either going to be “John Wick Is So Tired” or “James Bond Could Make You Some Pretty Good Eggs.”

Where did you write this poem?

That glissade is in there because I was writing in the car, waiting to pick up my daughter from ballet class. I write all over—sometimes even at my actual desk. I have a print from Bas Jan Ader’s I’m too sad to tell you on the wall. There’s nothing better to stare at when things are going badly.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or to friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say about them?

I showed it to my husband. He’s a math guy and doesn’t read poetry, but he’s usually right about my writing. When he read the first draft, he liked the first half but said he “didn’t get” the ending. Reading that draft again now, I see what he meant.

That version was maybe more like a novel or a short story. We’ve started with John Wick, but by the end we’re lost in the desert. It’s chatty, reaching for all the conversations that are being missed—the speaker wants to watch John Wick and tell the lost person historical asides about nuclear bomb testing sites. Of course they do, but that’s for a novel. In the context of a poem, it’s too much, too close together. I’m hitting the meaning-gong too many times. John Wick (the character, the movies, the Keanu) is so good, and the poem is about this one feeling of where-are-you-right-now-how-could-you-miss-this-one-particular-thing, so we need to stay with John Wick and forget the desert.

After I found an ending that felt more specific and focused and safely clear of novel/short story/essay territory, I sent a copy to my agent, Jon Curzon. He told me he’d once made an Instagram account called Keanu Leaves, which was just full of pictures of Keanu Reeves waving goodbye.

How else did the poem change over time?

I wrote it without stanzas at first, and then decided to break up the poem following the speaker’s thoughts—where the thinking shifted, or where I thought they might pause or take a breath. The stanzas got me closer to the person speaking—they helped me hear how the speaker would say the lines.

As useful as they were, though, the stanzas made the poem too dramatic. They looked like they were trying too hard. We’re starting with a hatchet thrown at someone’s face—we don’t need the additional histrionics of white space. Then it was all playing with line breaks. One of the drafts has two lines with single words. It’s not that I was thinking I might eventually end up with one-word lines—it was that I was breaking the lines up everywhere and leaving them for a while to see how they looked. I was just pushing things around, moving lines back and forth and reading it again every few days. I would open the document, break up lines, and leave it for a bit.

Once I got the poem to the point where, when I looked at it fresh, there wasn’t anything I wanted to change, I sent it off and left it for dead.

Kyra Wilder is the author of the novel Little Bandaged Days.

March 28, 2023

My Ugly Bathroom

Photograph by Sarah Miller.

My bathroom is ugly. My bathroom is so ugly that when I tell people my bathroom is ugly and they say it can’t be that ugly I always like to show it to them. Then they come into my bathroom and they are like, Holy shit. This bathroom is so ugly. And I say, I know, I told you.

Let me list the elements of my ugly bathroom: the sink has plastic handles and it’s impossible to clean behind the faucet. Or, you can clean behind it but it’s difficult, so it’s always grimy. The sink itself, the basin, is made of some sort of plastic material that probably used to be white and is now off-white.

The water pressure in the sink is almost nonexistent. I’m not sure if this has anything to do with the sink itself but when your bathroom looks like this you don’t think, Oh wow, I really want to improve the water pressure, because bad water pressure goes with the decor.

The textured ceiling looks like a birthday cake that was frosted with canned white frosting by a person who hates whoever’s birthday it is.

The shower is maybe the worst part of the bathroom. When people come to visit us we have to tell them that the shower is disgusting and even then they cannot manage to remember not to look crestfallen when they see it. It too has fairly poor water pressure and is really tiny and the inside of it is cracked and the shelves in it are too small to fit bottles of shampoo and they are always falling down when you are taking a shower and if you have your eyes closed you think you are being attacked.

The floor is linoleum and cracked all around the edges.

I have left out the most important detail which is that this bathroom has redwood paneling that goes up to about four feet and then the rest of the bathroom is painted the same color as the ceiling. One tiny window looks out onto nothing. The curtain on it is the same curtain that was here when we used to rent this place. We lived here for a long time before we purchased it from the owners. It’s one of those two-part curtains that has a small shade across the top of the window and a smaller one that hangs below it. I can’t even tell you what it looks like, which should embarrass me, but I am always too tired to think about it.

I am glad that it is there because we used to live next door to this real asshole and I didn’t want him to see me naked for my sake, and we are about to live next door to some nice people and I don’t want them to see me naked either for their sakes.

We have a new kitchen. I’m not going to sit here and lie and tell you that I don’t really love our new kitchen. When I was growing up my parents never redid our kitchen. It wasn’t a very efficient space for cooking or hanging out in. It was annoying. I was like, You guys both have jobs, let’s fix up the damn kitchen.

I like having a beautiful kitchen that’s really easy to cook in. I appreciate the original placement of tiles that my partner did, which I consulted on, and I like how the garbage can pulls out from under the counter and you can just sweep scraps into it, and I like having a dishwasher, which I have never had as an adult until just a few months ago and which has changed my life. So I don’t want to say I don’t take pleasure in comfort and beauty. But I want my shitty bathroom to stay the way it is.

I get so sick of everyone thinking that everything they use has to be nice. Can’t some stuff just be crappy? Why do we have to get rid of perfectly functional stuff just so that every corner of our vision can twinkle with magic and possibility?

I don’t think having an ugly bathroom makes me a good person. It just makes me someone who is able to feel satisfaction with one specific place that is far from perfect.

There is much that I want. Some of it would make people think I am shallow and self-serving, and some of it would make people think I am deep and caring and full of desperate hope. My bathtub is nice in the sense that it is large and porcelain. It is the bathroom’s best feature. When I am in this tub I can pretend that I don’t want anything at all, that I am perfectly satisfied. If the bathroom were nice, I would start thinking about all the things that aren’t. This sounds absurd, but as a very tense person, I know exactly what conditions can relax me. It is necessary for me to protect these conditions. I do not have a good job right now, so there is no present danger of the bathroom being renovated. But I will be vigilant when there is.

Sarah Miller is a writer who lives in California. She writes a Substack.

March 27, 2023

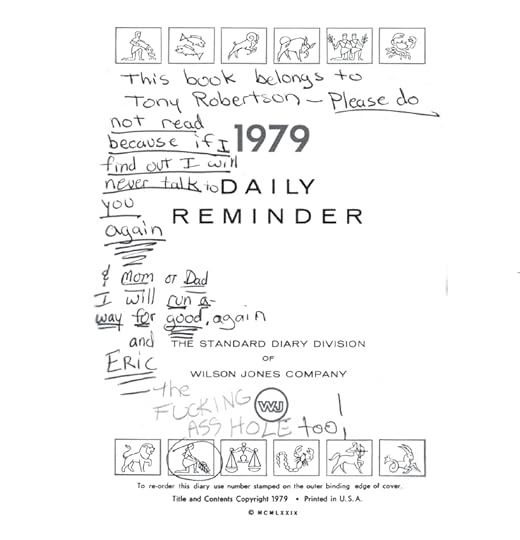

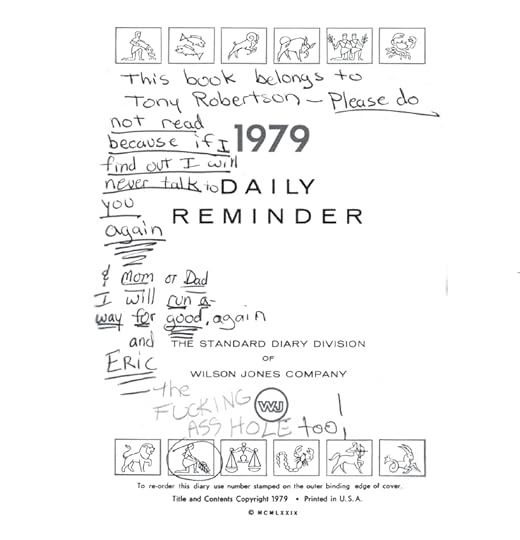

I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear

Courtesy of Semiotext(e).

I met Sean DeLear when I was twenty-four, in this house across from the Eagle in Los Angeles—I remember Sean talking about the LA scene, me asking him if he had a Germs burn (I don’t remember the answer), but also being very struck by the fact that up until that point I had probably met only a couple dozen Black punks but never anyone of Sean De’s age and with their poise. Even in Stripped Bare House at 2 A.M. and being festive she just commanded this kind of magic and glamour—it was definitely something to reach for and to aspire to. We don’t always clock these things when we are younger, but the mere presence of her let me be hip to the fact that I could be beautiful, Black, and punk forever—and in fact, it would be the best possible path to take.

It had been mentioned to me by Alice Bag (of the Bags, duh) that Sean was amongst the “First 50”—that seminal group of LA kids who were the first freaks to go to punk shows in Los Angeles and the geniuses of LA punk. Being a total-poser nineties punk I can’t even wrap my head around the dopamine effect of being in the mix when it all felt new—when Sean first started taking the bus out of Simi Valley and going headfirst into the scene for shows in Hollywood. How very frightening and liberating it must have been at the time for her, but of course I think Sean De was way beyond the title “trendsetter”—the word for her is MOTHER, forever, for sure, and for always.

What is contained in the tiny pages of this book is a blaringly potent historical artifact of Black youth, seconds before the full realization into the scary world of adolescence and inevitable adulthood. Uncomfortable in parts? Yes, of course. I remember in eighth grade reading The Diary of Anne Frank—the uncensored version, which was withheld from the public until her father’s death because he stated he could not live with the most private parts of his adolescent daughter’s diary being consumed by the world. There is a certain sense of protection I feel for baby Sean De’s most private thoughts being so exposed; however, so very little is written about the lives and the bold sexuality of young queers, and specifically of young Black queers, that I also have to give regard to the fact that there is something ultimately explosive about this text. It also denotes the intense singularity of its author. A gay Black punk one generation AFTER DeLear, at the age of fourteen I was rather content staring at a wall and obsessing over my Lookout Records catalog—I can’t even comprehend a gay Black kid some thirty years before planning to blackmail older white boys’ dads for money for acting lessons. Okay, like first of all, YAAAAAAAS BITCH, and second, this level of forward thinking is what propelled Sean De to become the scene girl to end all scene girls. I do have to imagine what level of this diary is real and which parts sit in an autofictional space—did she REALLY fuck all these old white dudes? Or was it a horny and advanced imagination at play? The only real answer is WHO CARES. I think one of the most magical things about Sean De was that her imagination and her fantasy world were so absolute. The world she was spinning always BECAME true—this is the beauty of a shape-shifter, and she was a noted scene darling and muse for this reason.

Now amid all this magic, of course, was her fair share of trials and tribulations. Sean related to me that when her band Glue’s music video for “Paloma” debuted on MTV’s 120 Minutes, a higher-up in programming made a call to make sure that it was never shown again—and how sad.

Now, let’s consider that Sean De’s performance did not exist in a vacuum—I mean, if there was room for RuPaul, why not for Sean De? Certainly by the nineties there was room for a punk rock gender-defying Black child-gangster of the revolution—or then again, maybe not. Whereas RuPaul was relegated to the dance world, Sean De made rock and roll her drama—and rock and roll to this day REMAINS (disappointingly) the last stronghold of segregation in music. In a post-Afro-punk reality this should not be the case, but as desegregation proves itself to be a one-hundred-year period, Sean De’s struggle to claim solidification and recognition in the world of SoCal nineties music comes as no real surprise. But also, as we are in an intense period of rediscovering buried histories and legacies, Sean De’s is one of great note, triumph, and inspiration. As a matter of fucking fact, she is the Queen Mother of alternative music, and in whatever higher realm of existence she is currently existing in, I can only imagine the sound of great explosions and bells ringing as she is gluing on her ICONIC eyelashes and receiving her flowers.

At the time of Sean De’s death, I actually got a handful of her eyelashes, which I promptly put on my altar for the dead. I collected every zine she was in in the nineties and the Kid Congo record of which she was the subject, and I got to read and relish in the world of this great artist as a teen. I don’t know how I got so lucky as to share a planet for a brief time with this punk-rock fairy godmother, but you best believe that I pray to any god listening that I am grateful for such. Long live Sean DeLear.

—Brontez Purnell

Monday, January 1, 1979

Happy New Year Tony it is now midnight and one second. Well this is my first diary and I will write everything that happens to me in 1979. Will write tonight Bye … Well I am going to bed now so today there was a bitchen earthquake that was 4.6 on the Richter scale. Me and Terry went bowling today and me and Kim got in a fight on the phone. About Ken (fag-it) P. Kim still likes him even though he was going to ask her to go with him but he didn’t. I thought of a name for you, Ty short for Tyler who works at the bowling alley and who I have a crush on madly. I don’t know if he is gay or not but he is so so so so cute cute. Well I am going to go to bed now, so good night.

Love,

Tony

Thursday, February 8, 1979

Dear Ty,

Today I did the long jump and got almost fifteen feet, not bad. I had acting class today and I think the play will be okay. I hope I don’t forget my lines and my cues. Well if I forget, oh well—there is nothing I can do about it. Tomorrow I am going to go to Topanga Plaza and try to get a trick and if I do I will swipe all his money, or her money. And Chatsworth High is right across the street and I will go into the locker room and act like I am looking for someone and I will say I am from Great Falls, Montana. I am looking for David B. I hope I get some money or I might just rob a store for all you know. But I don’t think so. Good night.

Love,

Tony

Friday, February 9, 1979

Dear Ty,

Well I went to Topanga Plaza and was in the tearoom and stuck my cock out to this man and he was a cop and he arrested me for masturbating in a public restroom. Can you believe it? They took me to the police station handcuffed then they called my mom and she had to come get me. She asked me if I thought I was gay and I told her I don’t know. I went to the high school and could not find the locker room and there were a lot of hunks. Then at about 2:30 A.M. I got my mom’s keys to the Zee and went for a little bit of a spin. It was so bitchen at first. I almost hit a car and from then on I was very careful. I went about twenty-five miles. I went to Simi Bowl and there was no one and then over the hill to Rocket Bowl and they were not open. I came home and Mom went through my room and called Dad.

Love,

Tony

Saturday, February 10, 1979

Dear Ty,

In the morning dad was here and he gave me a lecture about why I went over the hill and for what. I don’t know how to tell them that I think I am gay. I don’t think I will tell them at all. I had so much fun driving last night. Dad said “You don’t know how to drive,” that is what he thinks. Oh well. I went to bowling today and I was the only one there and we won two games. I bowled a 115, a 149, and a 169, not bad. I did not go in the tearoom that much because of yesterday over the hill. But I did see this one man’s cock—not bad about six and a half inches long, not that thick at all. Well tomorrow is the big day, I hope I can spin the basketball on my finger and don’t drop it. I hope it will be fun. I wonder how long I will be grounded for ditching and taking the car. When I find out I will tell you. This will be the first time this year. Good night.

Love,

Tony

Sunday, February 11, 1979

Dear Ty,

Well today was the big day of the play and it was okay and I didn’t drop the basketball when I spun it on my finger. I remembered all my lines I was so glad. Mom did not take my mags away from me that she found Friday night so I put them back where they belong and nobody knows where they are. We have a three-day weekend but I had four days. I am going to build a fishpond I started digging today and it is half dug up. I want to get little turtles and goldfish and all kinds of plants around it. I hope it does not cost a lot of money. I might get my phone put in but I don’t know. I wonder when I get Grandma’s piano I want to get it so I can learn to play super good. Good night.

Love,

Tony

Monday, February 12, 1979

Dear Ty,

Well I finished my fishpond now, all I have to do is get some cement and fish and turtles and a lot of plants to go all around it. I just thought of something—I have to get a good filter to keep it clean so I don’t have to clean it every day. I want to get a good one. I still don’t know when I get to be a free man again. I will probably be grounded for a week or two. I hope it is not long for my sake. It will be a long time I know her too well to let me off that easy. I meant to ask about the piano but I forgot again. I don’t think it will be too soon don’t you worry. I still love Tyler S. he is a total babe so is Dale B. and Victor C. I want their COCKS.

Love,

Tony

Tuesday, February 13, 1979

Dear Ty,

It started to rain today so I can’t do my pond today. I don’t think it will ever be finished but I can hope and pray. Today I was at Santa Susana Liquors and this old lady was looking at the naked ladies in the mags I could not believe it. She was probably a lez so who cares anyway. Then I went to Simi Liquors and they have the new Playgirl and the centerfold is a total fox with a huge cock and nice balls. I still don’t know when I will be a free gay person again. Probably a month or so; I hope not. I have to find out where Victor and Dale live so I can see them masturbate alone or together. I hope they do it together. If they do it together I will join them and spread it all over school and that will be hell for those two forever … Good night.

Love,

Tony

Wednesday, February 14, 1979

Dear Ty,

In office practice I did not get a chance to find out where Dale and Victor live. Well I went to McDonald’s for lunch and brought it back to school for me and Kim. Everybody was pissed off at me for not getting them something to eat. Oh well. Tomorrow we have our first big test in Mr. Billings’s class. I hope I get a good grade, better than Michelle’s. I still don’t know when I get to be a free gay person again. Right now, I am laying on my big nine-inch cock with a full erection—wish Dale’s cock was up my ass right now but no POSSIBLE WAY. Or Victor’s in my mouth so bad. I still don’t know when I get the piano. Max and Glenda think I broke into their house last night but I didn’t and I know that for sure so they can FUCK OFF. Good night.

Love,

Tony

Thursday, February 15, 1979

Dear Ty,

Nothing at all happened today. I still don’t know when I get the piano. Well, that’s all for tonight. I still love Tyler S. and want to see Dale’s, Victor’s, and Ryan’s cocks so bad. I want to find out where Victor and Dale live. Well, good night.

Love,

Tony

Friday, February 16, 1979

Dear Ty,

It has been one week since I got picked up by the pigs in the bathroom, and one week since I drove the car at night, and one week since I have been grounded. I still don’t know how long I am grounded. I think I will quit my paper route. I am so sick of Mr. Drunk, I am ready to just quit at the end of the month. I got Victor’s and Dale’s address. I can’t find either streets so I have to get a map of Simi Valley. Well, good night.

Love,

Tony

Saturday, March 3, 1979

Dear Ty,

I went to bowling today and we won all four games. I bowled a 143, a 115, and a 143, not bad … I hope my average goes up. We are at Dad’s house right now; I went out tonight. It was a total dud, but one thing I liked was there were a lot of cars and people out on the streets not like in Simi. I was walking home and I met this guy but he was not gay, I asked him and he did not get mad because he was higher than the clouds on coke. But other than him it was a dud. They fixed the hole in the wall at the bowling alley by putting a piece of metal over the hole and welding it. Well, good night.

Love,

Tony

Monday, March 5, 1979

Dear Ty,

I finished collecting today and I think Mark J. is gay. He is always in his room. If he is in school he must study a lot but that is still a lot of studying. I have to ask him one day if he is gay if I get the nerve which I doubt I will. Well we went to court today and I have to go to counseling again. See, they did not do nothing like I said. I forgot to ask Mom how much longer I am grounded, I have to ask tomorrow. I hope Mark J. is gay, he is such a cutie I cannot believe it. Now I have a crush on (in order) Dale B., Tyler S., Mark J., and Victor C. I love them all anyway. Good night.

Love,

Tony

From I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear , edited by Michael Bullock and Cesar Padilla and with an introduction by Brontez Purnell, to be published by Semiotext(e) in May.

Sean DeLear (1965–2017) was an influential member of the “Silver Lake scene” in eighties and nineties Los Angeles before moving to Europe. In Vienna, he became part of the art collective Gelitin and devised a solo cabaret show called Sean DeLear on the Rocks. DeLear was a cultural boundary-breaker whose work transcended sexuality, race, age, genre, and scene.

Brontez Purnell is a writer, musician, dancer, filmmaker, and performance artist. He is the author of a graphic novel, a novella, a children’s book, and the novel Since I Laid My Burden Down. Born in Triana, Alabama, he’s lived in Oakland, California, for more than a decade.

I Could Not Believe It: The Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear

Courtesy of Semiotext(e).

I met Sean DeLear when I was twenty-four, in this house across from the Eagle in Los Angeles—I remember Sean talking about the LA scene, me asking him if he had a Germs burn (I don’t remember the answer), but also being very struck by the fact that up until that point I had probably met only a couple dozen Black punks but never anyone of Sean De’s age and with their poise. Even in Stripped Bare House at 2 A.M. and being festive she just commanded this kind of magic and glamour—it was definitely something to reach for and to aspire to. We don’t always clock these things when we are younger, but the mere presence of her let me be hip to the fact that I could be beautiful, Black, and punk forever—and in fact, it would be the best possible path to take.

It had been mentioned to me by Alice Bag (of the Bags, duh) that Sean was amongst the “First 50”—that seminal group of LA kids who were the first freaks to go to punk shows in Los Angeles and the geniuses of LA punk. Being a total-poser nineties punk I can’t even wrap my head around the dopamine effect of being in the mix when it all felt new—when Sean first started taking the bus out of Simi Valley and going headfirst into the scene for shows in Hollywood. How very frightening and liberating it must have been at the time for her, but of course I think Sean De was way beyond the title “trendsetter”—the word for her is MOTHER, forever, for sure, and for always.