The Paris Review's Blog, page 57

April 28, 2023

Michael Bazzett, Dobby Gibson, and Sophie Haigney Recommend

Pete Unseth, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I don’t usually write to music. I’m too susceptible; I find it can give what I’m writing a false, unearned resonance, like slipping a poem into Garamond to make it “better.” But there are two songs that are rhythmic enough, each in their own way, that I sometimes put on a loop when I’m revising. There’s something about the cadence and the breath in them that works for me, that creates a kind of chamber that keeps the outside world at bay. And though I’ve heard “writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” (a quote so apt, it’s attributed to no less than a dozen people), here goes:

“Spiegel im Spiegel,” 1978—Arvo Pärt

The piece—in English, “Mirror in the Mirror”—begins with a simple ascending arpeggio, little triads that subtly alter, reflected back and forth like light on water, a mirror looking into a mirror. The melody stretches over and through the scales, extending like a long breath. The left hand on the piano arrives, eventually and sparingly, to ground the upward yearning, trees reaching toward light from the roots. The work is minimal in its composition, yet never fails to tug me out of my momentary preoccupations into a broader sense of time, drawing me into eternity through the little window of now. There are many beautiful recordings, but Angèle Dubeau’s version is a good place to begin, I think. If you put it on and close your eyes, everything will soon feel softer.

“Fleurette Africaine,” 1962—Duke Ellington

Mingus starts the song with a spiraling, skeletal stuttering on the upright bass, a sleeping animal rousing itself, a little tousled. It’s all very organic, the rise and fall of a breathing body. Ellington’s piano wanders in, elegant, stately. Max Roach’s drumming is the nest—he drums around the song as much as into it—weaving the thatch that holds the bird that sings the song.

—Michael Bazzett, author of “

Autobiography of a Poet

”

When Charles Simic died recently, I pulled his books from my shelf and reread them from the beginning. I thought I had long ago metabolized his poetry, but it turns out those early collections, especially, could still shake me. Simic, who grew up in Belgrade during the 1940s, lived in the vortex of the greatest horrors and atrocities of the twentieth century. His poems neither name nor catalog these historical particulars; instead, those events exert a pressure on the poetry by lurking just off stage, as though they have only just happened, or are about to. Simic had no interest in being the hero of his own poems, which are typically delivered from the perspective of a mystified fool gazing at the object world, uncovering its ancient and terrifying wisdom—those deeper dream meanings. His is a poetry so unlike our current period style! It provides the best reading experience: enchanting, unsettling. Start with Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk, though any of his books from the late 1970s or early 1980s will do. Each is a marvel.

—Dobby Gibson, author of “ Small Craft Talk ”

You can read our Art of Poetry interview with Simic here .

Here’s an experience I can’t exactly recommend but which has its particular pleasures: getting really sick, lying flat on your back with an eyeshade on in the afternoon, and listening to the audiobook of Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast. I did that for the first time when I had a concussion in college while I was forced to lie in a dark room for a week without reading or writing. I have no idea why I chose this particular text. Whenever I have tried to pick up the actual book, I am less sympathetic to it—I find it treacly, which it often is. But listening to it, especially in a state of heightened vulnerability and self-pity, I am moved by its cadences and easy romance. One passage, on skiing, that I like to listen to, but which works alright on the page too:

I remember all the kinds of snow that the wind could make and their different treacheries when you were on skis. Then there were the blizzards when you were in the high Alpine hut and the strange world that they would make where we had to make our route as carefully as though we had never seen the country. We had not, either, as it all was new. Finally towards spring there was the great glacier run, smooth and straight, forever straight if our legs could hold it, our ankles locked, we running so low, leaning into the speed, dropping forever and forever in the silent hiss of the crisp powder.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

April 27, 2023

Are You Thunder or Lightning?

Sixteenth Century Engraved sun and moon image. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I have always liked categorical statements that are obviously wrong. When someone says to me “This is the way the world works,” I get very excited, even though of course nobody knows how the world works. Or, even better: “There are only two types of people in the world.” This statement is usually followed by two binary qualities that could be used to define and divide all of humanity. Such a proposition is clearly ridiculous and, to me, deeply appealing. This is perhaps why my favorite game is called Dichotomies.

The game originated because my friends and I are always talking about our other friends. One night my friend Nick and I began idly categorizing people we knew, somewhat arbitrarily, as either thunder or lightning. We knew immediately who was which: Nick and I are both lightning. Our friend Ben: thunder. Alex: lightning. Graham: thunder. Lily: thunder, though maybe she has a bit of lightning too? We discussed and debated. This dichotomy is a good one in part because of its ambiguity; not everyone interprets it quite the same way, but everyone has a strong instinct for what each category might mean, and a sense of who might be which. Our attempts at categorizing people opened up some interesting questions: Was so-and-so outgoing, or actually quite shy? Did he make a big impression at first, or grow on you later? Was there a certain kind of power in being thunder and a different one in being lightning? Which would you rather be? And why was it so easy to tell the difference?

So I began to think of other interesting binaries. Another friend and I decided that some people are “men about town” and some people are “helluva town guys.” (Gender-neutral.) As I see it, a man about town is someone who always has fifteen plans that they’re running to, someone who is excited to meet new people and try new things, someone who is essentially oriented toward the public sphere and the allure of the untried and untested. At a party, they will end up talking for hours to a fascinating stranger who they will never see again, but they’ll remember the conversation forever. A helluva town guy is someone who likes to go to the same bar every weekend and drink ten beers with their best friends and say, “Man, life is so good!” But they are also someone who might know the secrets of the city a little bit, who might take you to an unremarkable-appearing restaurant that turns out to be special. They are your quintessential regular; they return, and they identify with the fact of their continuous return. Sometimes helluva town guys might find themselves living man-about-town lives—but at their core, they remain helluva town guys, even if they’re going out five nights a week. Dichotomies are, crucially, not about preference; they are about someone’s essential essence.

All summer long I thought of other ways to divide the world in half: New Hampshire/Vermont, Picasso/Matisse, punk/hippie, still/sparkling, IPA/lager, Beatles/Stones, France/Italy, Bob Weir/Jerry Garcia, glamour/charisma, hater/enthusiast, ellipsis/etc., elusive/available, green/blue, beer/shots, Yankees/Mets. Many of these pairings betray my own particular interests—you could endlessly reformulate them, and in fact I do. The best ones are pairs that are not actually quite opposites but proximate and different. So I began to play this game with people, often in groups, where you might ask someone to go around and categorize everyone, even people they don’t know well. Or, if there are two of you—say, on a date—you might go through them together and discuss who falls on which side of the aisle. I began to play it endlessly, in almost any circumstance. I started keeping a note on my phone, a running list I could pull out when someone said, “Okay, do another one.”

Maybe this sounds boring, or annoying (boring/annoying is a classic dichotomy), but I’ve had some of the most interesting conversations of my life while playing this game. It helps that I am interested in nothing more than people, and especially the people I know, and talking with the people I know about other people we know. So I am an obvious candidate for the game Dichotomies, but I’ve met very few people who didn’t like it at least a little. Sometimes the discussion can get quite heated, for obvious reasons. We are trading in stereotypes and lazy characterization here. You might put your foot in your mouth by labeling someone France who is proudly Italian, or telling someone they are lightning when they perceive themselves as thunder. In fact, one of the things I have learned from playing the game ad nauseum is that people very often want to be the one they’re not. This is not really surprising—it is a fact of life that those of us, like me, who are Vermont (fancy cheese, Phish shows, Birkenstocks) would prefer to be a bit more New Hampshire (fireworks set off in cornfields, rusting trucks, camping by the lake). Most of us have a little of both, and even the states of Vermont and New Hampshire have plenty of both. But the magic of Dichotomies is that you have to draw a line in the sand. I think this is part of what the game is all about for me: I am tired of ambivalence and equivocating, even though I am prone to both of those things. We are always being asked, often appropriately, to recognize nuance, to see that people have many different sides and qualities. Okay, fine, obviously. But sometimes I just want to know something solid about the way certain people are in the world, even if it is essentially meaningless, like whether someone is wood or glass.

One night a friend and I got ourselves into trouble when we made up a new one: Hot or funny? It was obvious to us immediately—she was hot and I was funny. Which is sort of strange, because she is very funny, one of the people I laugh most with; she would also probably say that I am hot, and in fact immediately did upon making her pronouncement. But the hot/funny dichotomy is not really about whether you are hot or funny—assume that you are both, or neither, or mostly just that it’s irrelevant. The dichotomy is about how you present yourself, what you choose to foreground, and what others see in you most; it’s a mix of factors you can control or can’t, it’s about what you decide to do with what you’ve got. The results of this complicated amalgamation put you, always, on one side or the other. She and I knew right away that this was an evil dichotomy, and quite an interesting one. It cuts far too deep, if you have ever been insecure about whether you are attractive—and who hasn’t?—or worry about whether you are entertaining—and who doesn’t? Either answer is kind of a bad one, especially because you’ll likely wish you got the other one. So I wouldn’t recommend playing this one in public, or telling other people which they are. But it is a question to consider, and I bet you know the answer, because there is always only one: are you hot or funny?

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

April 26, 2023

Who Was Robert Plunket?

President Harding with pet dog Laddie being photographed in front of the White House. National Photo Co., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I might not have read a single truly funny novel that year if my friend hadn’t stopped by my Los Angeles porch one afternoon carrying an out-of-print copy of Robert Plunket’s comic masterpiece, My Search for Warren Harding.

We were in the worst of days—the depths of the pre-vaccine pandemic—and our world was on fire, both literally and figuratively. The copy of the novel that my friend, the writer Victoria Patterson, handed over to me looked the way we all felt in those days: yellowing, battered, dusty from too long in storage. Tory bellowed through the muffling fabric of her N95 mask that it was one of her favorite novels—and really fucking funny.

I needed funny. I opened the book a few weeks later—and despite my allergic reaction to the mold in the edition, kept reading for the next 256 pages. When I was done, I sat in a kind of silent, focused delight. I held in my hands one of the best, and most invigorating books I’d read in years, and certainly the funniest—and yet, how was it out of print? Why had I never heard of this novel before now? (Later I learned Tory had actually written an excellent piece about it for Tin House magazine in 2015.) Why had it disappeared so fully from the literary landscape? And what did that say about this literary landscape if it could bury a book like this? Most intriguingly: Who was Robert Plunket?

The jacket bio for Plunket’s second (and, so far, last) novel, Love Junkie, published in 1992 and also out of print, reads:

Robert Plunket’s first novel, My Search for Warren Harding, immediately established him as one of America’s most promising novelists. Unfortunately, the promise soon faded, and he now lives in a trailer in Sarasota, Florida, where he ekes out an existence as a gossip columnist, covering everything from gala charity balls to KKK meetings. He has also served on the boards of Sarasota AIDS Support and the Humane Society of Sarasota County, and is currently running for election to the Mosquito Control Board, District 6.

So much for literary fame. There are few interviews with Plunket online. In one of the only I could find—published by the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2015—he explains the inspiration for the novel to writer Michael Leone.

“Obviously, it’s based on The Aspern Papers,” Plunket explains.

The Aspern Papers, the celebrated novella published by Henry James in 1888, is set in nineteenth-century Venice, where an unnamed narrator seduces a young woman in order to gain access to her spinster aunt’s trove of letters by her dead poet-lover.

Plunket goes on to say, “It was always one of my favorites, but most important, it spoke to me in a special way. I couldn’t figure out why until one day it hit me. The guy’s gay! Of course! Now the book made perfect sense. His relationships with all the women characters were those of a gay man. Now, not an openly gay man or even a consciously gay man. But a man who was just not heterosexual at his core. I don’t think Henry James realized what he had done, or how well he had done it, which made my discovery even more exciting.”

In Plunket’s retelling of The Aspern Papers, he sets his novel in late-seventies Los Angeles. The author himself was just emerging from that era when he wrote the book. It came out in 1983: the same year the national craze for Cabbage Patch dolls reached its pinnacle. The same year Vanessa Williams was crowned, then promptly decrowned, the first Black Miss America. The same year Ronald Reagan decreed Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday and Michael Jackson moonwalked for the first time on national television. The same year Reverend Jerry Falwell described AIDS as “the gay plague.”

Plunket’s book, in other words, emerged out of a culture of contradictions—a world of both hedging progress and conservative backlash, an America of trash and spectacle. Which is maybe why the novel, forty years later, feels so startlingly contemporary.

***

Sensitivity readers, be warned: the protagonist of this novel, Elliot Weiner, is cruel, racist, fat-phobic, homophobic, and deeply, deeply petty. In the novel’s opening, we find Weiner standing on a scenic lookout in Los Angeles with his friend Eve Biersdorf staring through binoculars at a large, dilapidated home in the distance. Whatever mischief he’s up to, he says, “it was Mrs. Biersdorf’s—Eve’s—idea.” Weiner, we soon learn, is an East Coast snob and middling historian who has come from New York to Los Angeles on a fellowship. He holds himself in high regard, but the more he brags about his academic career—“Suffice it to say that I teach at both Mercy College and the New School, and I feel that speaks for itself”—the more we sense desperation: “Some unfortunate comments have gotten back to me about my ‘qualifications.’” Elliot Weiner is hoping to retrieve some lost love letters between President Harding, traditionally ranked as the worst of presidents, and his secret mistress, Rebekah Kinney, the owner of the house in the view of their binoculars. Weiner soon learns that Kinney is alive, but now a cranky octogenarian who wears rhinestone sunglasses and spends her days in her crumbling mansion shouting at her Mexican servant from a squeaky wheelchair. Weiner believes the old woman still possesses the love letters and other Harding-related papers, and is hiding her treasure somewhere in her crumbling mansion. And he will do anything to get his mitts on those letters, even “rape and pillage,” as he’s hoping a discovery like this can propel him to academic stardom.

As the novel unfolds, Weiner’s madcap effort to obtain these papers propels the absurd, picaresque plot. He rents out Kinney’s dilapidated pool house and cozies up to her granddaughter, a naive young woman named Jonica whose ample flesh disgusts him. But he’s willing to grit his teeth and seduce her if it means getting to her grandmother’s historical smut.

Weiner is cruel about Jonica from the beginning, describing her as “a fat girl … wearing baggy green paratrooper pants … and a lot of plastic bracelets that added to the general din … She talked like a real California girl, no inflection, lots of r’s.” Yes, Weiner is unabashedly cruel about innocent Jonica. He despises all she represents—fatness, the West Coast, gullibility—and yet he begins to court the poor woman, to prey on her neediness. Soon they are romantically and sexually involved—and he’s that much closer to his prize and becoming a renowned historian.

The bare bones of a plot is so often just a skeleton for a novelist to hang up their observations. The more streamlined and beautifully elegant a plot—and in the case of My Search for Warren Harding, the plot simply boils down to a single character pursuing a single, tantalizing object—the more tangents the author can take. And the tangents in this book are everything. They let us see Plunket—with his lacerating wit—send up the entire culture of Los Angeles at the turn of the eighties.

But with every parody of the culture around him, Weiner is the biggest joke of all. One of Weiner and Jonica’s early dates is to an avant-garde feminist performance—an audience-participation play called All My Sisters Slept in Dirt—A Choral Poem, performed at the LA Women’s Theatre. “Then, all of a sudden, people started streaming in like they’d just got off a bus. Women mostly, with severe haircuts and aviator glasses. It hit me what an important moment in feminist fashion it was when Gloria Steinem dropped by her optician’s and said, ‘I’ll take those.’” The satire in this scene is perfect, and we are aware, too, that Weiner, who has a sweating problem and is wearing a silk shirt, has strapped cut-up Pampers diapers to his underarms to absorb the sweat. Whenever the author is vicious about the people around him, he humiliates Weiner a little more. After the date, Weiner expresses his repulsion toward Jonica:

When I got back, she was still lying on the rug, looking up at me.

What can I say? You can guess what happened next.

As for her body, I won’t go into details but will say this: she had a lot of dimples. Everywhere.

And yet the reader knows Weiner is the one with the soggy Pampers taped under his arms.

In fact, Elliot Weiner is depicted as the most deliciously awful of New York City neurotic bachelors. For one, he puts his garbage in the refrigerator so it won’t stink and attract roaches, while the girlfriend he’s left back in New York, Pam, is the consummate beard. “When we first met, we discovered we had a lot in common, including the fact that our brothers had attended the same basketball camp although at different times.” They were clearly meant to be. Pam even indulges his true passion—which is for “Morris dancing … a type of old English folk dancing, always performed by men. It can get pretty wild, since it involves a lot of swinging of clubs.”

What’s wonderful about Plunket’s first-person narrator is how far beneath the surface his dishonesty lies. His attraction to men is hinted at beautifully, hilariously, but always cagily, never consummated. He has lied so much—so profoundly—and for so long that his attraction leaks out in twisted bromances with straight, working-class men. He leers at them, ingratiates himself toward them, describes their biceps and the length of their shorts, but his desire reveals itself sideways. His defenses have been shored behind this original lie, as he looks down on everyone and on Los Angeles itself. In the gaps between his observations, the silences, the truth about Weiner’s true self emerges. Behind the bluster and arrogance he’s a closeted gay misanthrope, blind to his own desires. While Weiner is not a likable character, the story doesn’t ask you to admire or sympathize with him. Yes, he’s a superficial, arrogant, closeted homophobe who refers to the one gay man he encounters as “the faggot.” He goes into long tirades, including an elaborate racist theory about the difference between Puerto Ricans in New York and Mexicans in LA (he prefers the Mexicans). Fat jokes abound. But it’s not empathy we are here for.

In his essay “Gay Sincerity is Scary,” Paul McAdory calls out the fiction of “gay sincerity”—that contemporary, humanistic, and, above all, earnest gay novel that revels in its own poignancy and tenderness. McAdory cringes in the face of such mawkish, heartfelt quasi-transgressive sentimentality, and asks: “Do we not grow tired, after so many rounds of this sentimental journey to the weepy, fantastical core of human experience? Might we not celebrate instead a more horizontal outlay of sincerity, mania, irony, horror, meanness, humor, etc. … In lieu of crying, a writer might try laughing, cackling, madly monologuing to the pool of cum on one’s tummy, coolly observing it, overanalyzing it for effect, playing in it, rejoicing in it …”

My Search for Warren Harding might be the insincere gay novel McAdory has been hoping for. Weiner is a low-key monster. He projects his self-loathing outward onto fat women and openly gay men. His views are problematic. His whole way of judging other people is reductive and snobby and scathing and unkind. Of course all books and works of art are in some ways a symptom of their times, and this one has the blind spots and cringeworthy moments that remind us of its 1983 pub date. But for those of us who are greedy for models of literary fiction that are actually funny, hungry for satire that stings, craving work that pricks and prods us awake—fiction that doesn’t bore us—the risk of not reading these rare works outweighs the risk of being offended.

And in the end, I don’t think you can read Plunket’s work straight-faced. Too often we still insist on reading the fiction of so-called “marginalized” authors as thinly veiled autobiography, or worse yet, a tool of self-help. We somehow still believe the queer novelist or the writer of color must share the moral underpinnings and opinions of the characters they create on the page—and when the character says or does wrong, we convict the author. But so much of the real pleasure of fiction lies in the nonliteral, meaning told slant—in double-talk and mischief and irony, all embedded in the elaborate lie.

First-person narrators are often best as liars. They are most interesting when they lie to the world and they lie to us and they especially lie to themselves. Weiner is no exception. And there is a particular pleasure in this novel of witnessing the cracks where Weiner’s self-delusion runs up against the reality of his true self.

Weiner learns nothing from his journey. He keeps judging, keeps lying, keeps grasping, keeps being petty. Part of what’s liberating about writing awful characters, grotesque characters who do grotesque things and learn nothing from their journey, particularly for those of us who are writing from the margins, is that dark satirical comedy resists the autobiographical gaze. In writing a perceptive satire—writing monstrous characters on downward spirals that never reverse course —we resist the pressure to remediate and uplift. We reclaim our right as artists to simply fuck shit up and walk away, laughing.

The first rule of improv is “say yes.” And indeed part of the perfection of My Search for Warren Harding, in part, is in how committed it remains to its premise and the persona of Elliot Weiner. Plunket says yes to the problematic character and he continually says yes to the absurd circumstances he puts him in. The story keeps saying yes to its own twisted logic and doesn’t ever shy away from the ugliness or limitations of Weiner’s vantage point.

In the real world we’re told we should empathize and see things from other people’s points of view. In a novel, the opposite is often true: the point of view is by necessity chauvinistic. It works most powerfully when limited by its own body and times and perspective.

My Search for Warren Harding feels like freedom because of its limitations. In reading a character so blind and blindsided, so prejudiced and self-absorbed, we are freed from our own sanctity, our own arrogance. The main character is a closeted white gay man with a narcissist’s insecure vapid center. In reading Plunket, we are freed from our own delusion that we are not all Weiner. That we are not all—somehow, someway—in the closet.

His novel anticipated and influenced much of what the culture would begin to find funny (and maybe what some of us are still waiting for the world to find funny). In our contemporary humble-bragging world of filtered selfies, virtue signaling, and good optics, we find increasing release, and comic relief, in fictional characters we are not asked to admire or envy—in characters so awful or amoral or vapid that the joke is on them.

The novel was a critical success upon its publication in the eighties. Ann Beattie and Frank Conroy wrote glowing reviews. Plunket, however, didn’t publish again for many years and instead dabbled in acting. His IMDb page says he is “best remembered as the timid gay guy” in Martin Scorsese’s dark comedy thriller, After Hours. He went on to get bit parts in other movies, then published a second novel, Love Junkie, in 1992; the rights were optioned by Madonna. Plunket moved to Florida and did not publish another book. Even still, My Search for Warren Harding continued to quietly leave its mark—passed around through some kind of comedic-literary whisper network, where it was adored by a small, select group of readers that included Amy Sedaris and Larry David.

Rumor has it that Larry David was such a fan of the novel he kept copies of it available in the Seinfeld writing room and told his writers to imitate the tone. It’s clear reading this novel that he even lifted details from the book, such as the absurd way that Seinfeld’s Elaine dances—clearly based on the novel’s depiction of how Weiner’s girlfriend Pam dances:

She is one of those people who ‘abandon’ themselves to the beat, clapping their hands over their head and emitting little yelps. To make matters worse, she studied modern dance in college and thus considers herself a Movement Expert. The thing she does—I can only describe them as Martha Graham routines. Her arms fly out into space, she makes sudden turns, then she half-squats, her head flung back in ecstasy.

After its publication, this novel did what so many great novels do: it shone briefly on the new fiction scene, long enough to be pilfered and imitated, long enough to be absorbed into the culture it would influence. And then, like so much source material, it disappeared, like the author himself, who retreated to Sarasota, Florida, where he has lived for thirty-seven years and involved himself in gossip and real estate writing, rhinestone and quilt collecting, and raising succulents.

“The literary marketplace is fickle, unforgiving, and often unfair, likely to reward the second-rate,” writes Victoria Patterson in her essay on Plunket. “In counteraction to this depressing reality, there’s also a beautiful and hopeful phenomenon, whereby a deserving book survives.”

When Patterson handed me Plunket’s half-forgotten novel that day on my porch, California burning and the world in decay, the out-of-print book had already been handed to her years before, pressed upon her by another writer. And I read it and pressed it upon a brilliant friend at New Directions and so here we have it, a redemption song.

***

In that one rare interview in the LARB, Plunket comes off like I’d expect: unpretentious, unfiltered, quick-witted, honest, and completely bullshit-free. He is deeply literary, loves literature perhaps too much to sully it with careerism. He talks trash about the books that are supposed to be funny but aren’t: “P. G. Wodehouse means nothing to me. I can’t get past the first page.” He throws shade at Jonathan Franzen: “I find the characters so stuck in middle-class angst that we are supposed to take seriously …” He is also transparent about the rules he tries to follow in order to write a truly funny novel. As he says, the funny novel must include a “slightly manic, deeply flawed first-person narrator”; it must “pay attention to rhythm—make the words dance,” and should include a “punch line every other paragraph.”

Plunket bemoans in the interview that “people don’t think anything ‘delightful’ can be serious. Yet the delightful works of art are exactly the ones that last, while the ‘profundity’ of any age dates quickly.”

This turns out to be true. The cosmic joke of Plunket’s delightful novel is still as fresh today as it was forty years ago. It is a gift to us—devoted readers of Los Angeles literature, of comedy, of queer literature, and of the literature of self-loathing—that it is finally being reissued now. You hold in your hands the paramount example of a comic novel. To all the greedy readers and writers, enjoy the ride.

From the introduction to My Search for Warren Harding, to be reissued from New Directions in June.

Danzy Senna is the author of several books, including the award-winning novel Caucasia.

April 24, 2023

Inertia

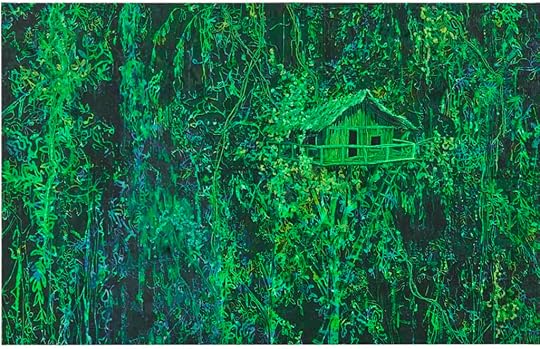

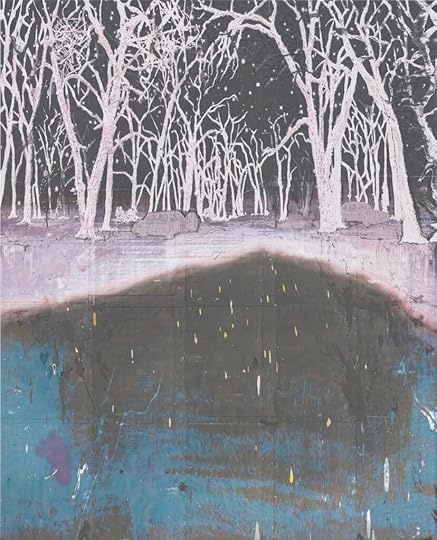

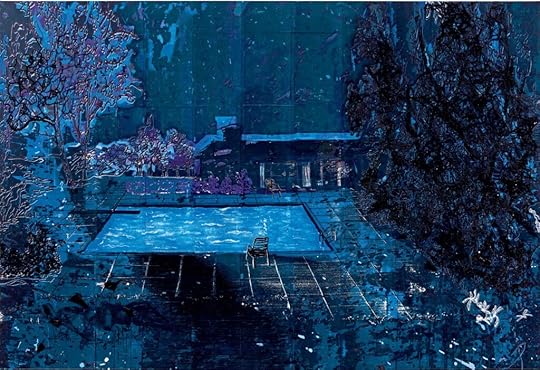

Michael Raedecker, solo 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

In a novel that she had been trying to read the night before, she’d read the description of a late spring day as a glittery day, and she thought of that as she was walking with her daughters, and the dog, up through the boulevards. It was turning from a warm into a hot day, even though it was still morning, and not yet summer. The dog was panting, and they took a break, to drink their bottles of water thrown underneath the stroller. There was something filmy to the skin of her daughters, she had dressed them that day in their lightest clothes, and later, she had promised, they could put on their swimwear at the local splash pad. Before leaving she had quickly pulled their hair off their faces, and now they kept on taking off their hats and handing them to her, and she would throw them in the bottom of the stroller. They needed to get their hair washed tonight, she observed, as she looked at them, their curls greasy with sunscreen. The children had decided they wished to dress alike, or in corresponding colors, and today they were wearing shades of yellow. They were mostly quiet, strolling down the street, the older daughter riding on the attached wooden platform with wheels that trailed behind the stroller that they called the skateboard. She had found a piece of dark yarn and was finger-knitting with it, which she loved to do, or tying a piece of yarn into knots, or wrapping it around and around a stick. It was beginning to be the kind of heat in which one went about in a daze. Sometimes the children wanted to get out to walk and she would hold their hands while their father pushed the stroller, which was laden with provisions for the day. It was such a beautiful walk that morning. The green of the bushes and the trees at this time of year seemed lush and overgrown. Because of this green canopy they were in the shade most of the time, until they had to cross major streets and intersections. She felt that they were walking in a bright encroaching greenness, and had the sensation that they were alone with the trees and the gardens. When she got home she was supposed to work on an essay she had been commissioned to write, on an artist who painted landscapes that felt wild and overgrown like this while remaining strangely suburban. His green paintings felt like they were set in the middle of a forest, often enhanced with black glitter, iridescent beads, and black and green embroidery. There were no figures in his paintings, although there was a narrative, however mysterious, and suggestions of places where children were once playing, or, perhaps, of the abandoning of these spaces, for an unknown reason. There were cars parked outside with their doors left ajar, pairs of tents and treehouses, chairs overturned. This interested her more and more, the strangeness of an emptied landscape, and how then to write of this emptiness.

Michael Raedecker, koan 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

One day recently, during the baby’s nap, she had read a book on eeriness, which suggested that the eerie takes place within a silent and unpeopled landscape. Because she had been thinking of these paintings by this artist she didn’t know who lived elsewhere, on this walk she realized she was beginning to see the outside world like his visions, that it had taken on their strangeness. The landscape in which she was walking with her family that morning appeared to glow. In the novel she had been trying to read the night before, a woman keeps seeing a figure in green everywhere she goes, and reading it she thought that she’d love to write a text to attempt to speak to these abandoned landscapes that glowed green, like a strange green light. On their morning walk she remarked to her family that it was so strange that there was no one around. It was so silent out, except for birdsong. She had a thought—that the landscape they were walking through was like the paintings she was supposed to write about, except there was no birdsong in the paintings. Or perhaps there was, the thought continued, but she couldn’t hear it in the silence of the gallery in which she had originally seen them, with only the sound of her children and of her footsteps on the creaky wooden floors. On the long walk they passed almost no one else on the sidewalk, if anyone at all. Perhaps it was because it was morning, her husband remarked. Or perhaps the heat. Maybe everyone was inside, in the blast of air-conditioning already, having no desire for the outside. But there were still so many cars on the street, she replied. More likely those families who lived in the large houses went to other large houses on the weekend, especially for the holiday, large houses that were even more remote, more rural, even more beautiful. But when did they enjoy their gardens? Today, because of the holiday, there were none of the crews working outside, as there had been the day before, none of the fumes or roars of their lawnmowers and leaf blowers that were so noxious to walk by. She waved at a sole woman who was gardening outside, a sturdy homeowner who had most likely been in that neighborhood forever, before the change. The beauty and care of the gardens here always surprised her, especially in the intensity of early summer. There was a wildness to so many of them, especially now, at the peak, the overgrown rosemary, the reds and pinks of the rosebushes, the fragile tendrils of peonies jutting out. She knew that there was artifice to this wildness, that it was cultivated, but still she felt thankful for its beauty. Lately she had felt overcome by the visual splendor of the flowering trees outside of the large houses, the surprise to these full open flowers, almost obscene. It made her feel dizzy, or perhaps it was the heat. She hadn’t drunk enough water that morning, after coffee. The day before at the farmers’ market she had purchased two bunches of peonies, such as were flowering now, one fuchsia and light pink and the other pure white with speckles of pink. They had spent the day watching them, enjoying them, and wondering whether ants would be needed to open the few remaining closed bulbs in the bouquet. This morning her oldest daughter and her husband had placed an ant from the sticky kitchen counter on one of the flowers, as an experiment. When she had first seen the paintings of this artist, on the walls of a gallery, while she was wearing the baby, holding the hand of her daughter, she felt moved by them, especially by the flowering trees, embroidered with hectic and voluptuous clusters of red and pink thread. There were also all of his pool scenes, with the chlorinated light of the blue, that she thought of the day before, when they had proceeded on their walk in the other direction, toward the larger mansions near the park, and passed by the house on the corner where her daughter had attended a birthday party almost exactly one year earlier, as she had been in the same preschool class that spring with the boy who lived there, with his older brother and their parents. The preschool had taken place mostly in the park, in the style of forest school that became popular last year, and they were sent videos by the teachers of children, bored and hot, standing near a monument or excitedly playing in the nook of a tree. Her daughter had joined much later, and was an outsider to the group, but still was excited to be invited to the birthday party, especially because of the pool. The mother had been incredibly nervous, outside of her skin, for her daughter, who couldn’t swim, swim classes being almost entirely closed the past two years, and was swimming around in the artificially bright blue hole of water, with the shudder of its waves, and so she had purchased her a life jacket for the occasion and insisted she wear it. The horror and terror of the pool, and yet how inviting it was, its coolness. The father, who was much calmer about such things, was the one to take her, but then she joined with the baby later, wearing a long muumuu with painted flowers, walking by the blue-tinged hydrangeas that hadn’t appeared yet, so it must have been a little later in the year. When she came upon them at the party her daughter was so incredibly happy in the pool, her skin having that soaked, buoyant feeling children getwhen they are swimming, but she could hardly watch her, teeth chattering, swimming around and around in a circle, her life jacket not worn, clutching a pink foam noodle. What a luxury, to have a pool, she thought then, and also yesterday, as they walked by the house, past the gridded gate, and heard sounds of children playing and splashing inside, although they couldn’t see anything. Pools have to be fenced in, otherwise children would drown, her husband said to her in response, or something to that effect. It was the first time they had heard the family out in the pool that spring. When they got home from their walk the day before, she sat on the steps and watched the girls gleefully chase after the bubbles their father was blowing, the youngest especially desperate to catch one. They were framed by the green overgrown bushes in the front garden, and when she narrowed her eyes, she could imagine a field of green, with only the iridescence of the floating bubbles.

Michael Raedecker, topophilia 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Staring at them, spacey, she thought perhaps she was seeing a painting. Her thoughts were filled with thinking of her children, of the future for children. The other day someone, another writer, who also had two children, had written to her, that perhaps they would all be living in the woods in five years, and she had thought of that, and somehow it got confused with the green overgrowth of the paintings she was thinking about. Away from some impending violence, and from the city, it was implied, and toward safety, although she knew, in that overgrowth, in those woods, there was violence as well. The next day her husband took the girls to the playground as she sat on the couch and tried to think about these paintings. She kept on being sent zip files to download of images of the paintings, even close-ups of the various textures, but they kept on disappearing because she would forget to look at them and then not know where the files had downloaded, so she kept on having to download them again. She couldn’t focus, clicking through the paintings on a screen, or focus on thinking about writing about painting, and she kept on refreshing the news over and over. She looked at a notebook, which also featured her children’s scrawled drawings and writings, and tried to read notes that she had written after reading an essay on writing about art that was written by a friend of hers. She couldn’t decipher most of her own handwriting, with its knots and swoops, like it was alien to her. There was a passage she had written down, “much like a tunnel or glittering vortex I’m talking about a pulling through of strangeness into strangeness,” and she kept thinking about this, about how to pull strangeness into strangeness. It felt like a connection she should follow, that she kept on reading about glitter. Was the glitter in the painting or the writing? What did this mean, glittery writing? She had wondered too, in this essay she was supposed to write, whether the paintings had to be in there. Should the paintings be here, in her writing? Or had they been diffused everywhere, in the atmosphere, in the air she breathed? She kept on trying to find these images of the paintings on her desktop and then chose not to look at the paintings or rather at the photographs of the paintings anymore. She needed to go outside.

Michael Raedecker, parallel visitation 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Outside was somehow where the paintings were, not inside. She decided to meet the children at the playground, off of the main thoroughfare in the neighborhood. As she began to turn onto the sidewalk, away from the streets with trees where they had been walking, there were now people everywhere. People, trash, dogs, street vendors, strollers of babies, boxes of groceries being loaded, people pouring out from the train. It was so much hotter, without the shade. She found herself wondering whether the artist in his summers experienced heat like this. There was an energy to his paintings that felt like humidity. She sat on the bench and watched the chaos of children gathered around the water spilling out from the spout, running around, yelling. After a while, they walked home, slowly, and sat on the porch, and she watched a smear of pink from the popsicle melt on the little tender face of her youngest. Inside, while dinner was being made, she watched the children, while trying to think of these paintings, and was somehow unable to stop her toddler from grabbing her pen and the book she was reading and take them only a short distance away to sketch inside of it. She was not able to grab the book back until it was too late. It was like she was stuck there, lost in her own inertia. She opened the book to see the scrawl across, and was somehow comforted that it was a passage about the writer’s young children, on page seven: “It’s also the nearness of that banana tree, of course, with its leaves so broad that any of them could enfold my youngest child, it’s also the imminence of a discovery. A golden dust floats above their heads. Their foreheads are curved and serene, their napes still pale.” Later that evening, after dinner, she sat outside, in the back, and stared at the green everywhere, almost like staring in the middle of a hole. It was silent, back there, except for the sounds of dogs barking, the joyous and sometimes incensed sounds of her daughters inside. She remembered when her first daughter was very young, she had begged their landlord to fill in the koi pond that he had dug into the ground beside the deck, and she asked that he transplant the koi elsewhere. She had visions constantly of her toddler daughter stumbling out there and drowning in the koi pond. They finally paid to have it filled in. There was now no sign of it anywhere, except for a thermometer that remained tied to the trunk of the Japanese maple that reached partly over the deck. She couldn’t imagine it having been there. All there was to stare at was green. Perhaps here, she thought, there was the hope of recovering the paintings in the landscape. In this outdoors that wasn’t really outdoors. She stared there for some time and wrote a few words. She heard one of her daughters screaming, in the bath, and went inside to help, spending time untangling the mass of a knot in her long hair.

This story was written at the invitation of Michael Raedecker, to be included in a monograph of his work, to be published by Phaidon in July. I first encountered his paintings at the GRIMM gallery in New York City, in March 2022. His work is currently showing at the GRIMM gallery in London, through May 20.

The novel quoted in this story is Marie NDiaye’s Self-Portrait in Green, translated by Jordan Stump.

The essay on eeriness referenced here is Mark Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie.

The essay on ekphrasis and writing quoted here is Danielle Dutton’s A Picture Held Us Captive.

Kate Zambreno is the author of The Light Room, a meditation on art and care, forthcoming from Riverhead in July 2023. Tone, a collaborative study written with Sofia Samatar, is forthcoming from Columbia University Press in November 2023. She is at work on a book of fiction, Realisms, as well as a series on zoos.

Mapping Africatown: Albert Murray and his Hometown

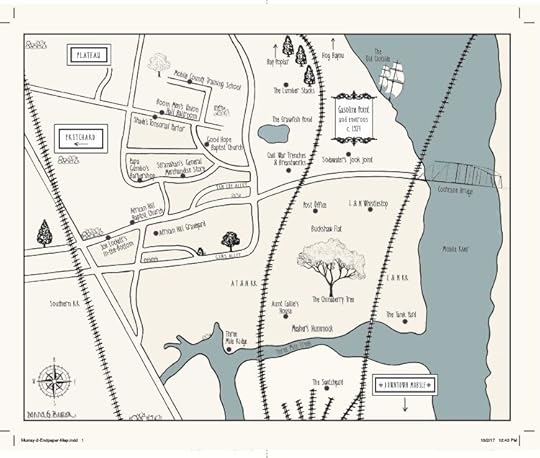

Map by Donna Brown for Library of America, with input from Paul Devlin. Based on a map drawn by Albert Murray in the 1950s or 1960s.

Circa 1969, the writer Albert Murray paid a visit to his hometown on the Alabama Gulf Coast, to report a story for Harper’s. Murray hadn’t lived there since 1935, the year he left for college. During his childhood, elements of heavy industry—sawmills, paper mills, an oil refinery—had always coexisted with wilderness, in the kind of eerily beautiful landscapes that are found only in bayou country. But as an adult, Murray was aghast to see how much industry had encroached. The “fabulous old sawmill-whistle territory, the boy-blue adventure country” of his childhood, he wrote, had been overtaken by a massive paper factory: a “storybook dragon disguised as a wide-sprawling, foul-smelling, smoke-chugging factory.” He imagined that the people who had died during his years away had been “victims of dragon claws.”

When Murray made this visit, he was in his early fifties and and was still at the beginning of his writing career. He hadn’t yet published a book. But over the next several decades, he would go on to write prodigiously, channeling into singular prose his memories of his old neighborhood before the arrival of the dragon.

The resulting work is a bildungsroman that unspools across four novels: Train Whistle Guitar (1974), The Spyglass Tree (1991), The Seven League Boots (1996), and The Magic Keys (2005). All four were reissued by the Library of America in 2018 (following a 2016 edition of Murray’s nonfiction). They share certain themes in common with other novels about boyhood, from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to The Adventures of Augie March; but thanks to Murray’s inimitable style, and the novels’ setting, there’s nothing else quite like them in American literature.

The novels also form part of a second canon: the growing body of literature on Murray’s neighborhood, a place of historical significance in its own right. That neighborhood is known as Africatown. Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon is also set there, and several books from the last twenty years have dealt with its history more systematically.

Within a mile or so of Murray’s childhood home was a settlement created by the men and women who came to the US on the Clotilda—the last known slave ship ever brought from West African to American shores. The community was established after the Civil War, as a kind of refuge, where the exiles, along with other people of African descent who had also been freed in the war and already lived there, could speak their own languages and appoint their own leaders. It’s the only community in American history founded and governed by West Africans who had personally endured the Middle Passage. It was known in the early days as African Town, and Murray recast it in his fiction as African Hill.

When Murray was a child, Cudjo Lewis, one of the last surviving shipmates, was still a regular presence in the area (he shows up in Train Whistle Guitar as the character Unka JoJo). And around the time Murray was twelve, Hurston spent time in the neighborhood, interviewing the elderly man for what would become Barracoon—which is an autobiography of Cudjo Lewis, as told to Zora Neale Hurston.

Over the last few years, interest in Africatown has been on the rise—thanks in part to Barracoon, which was finally published posthumously in 2018. The neighborhood still survives today, and although the paper mill Murray encountered in 1969 has long since shuttered, other industrial businesses have taken its place. The residential area is blighted and poor. (“It looks like a warzone,” one of Cudjo’s descendants has remarked.) But there’s an effort underway to transform it into a destination for heritage tourism. This effort was aided by the identification of the Clotilda’s remains, in the Mobile Delta, and by the Netflix documentary Descendant, which brought international attention to the neighborhood’s plight and the recent work of its activists.

And although Murray’s books are fiction, they are also fascinating lenses into a particular time in this place. In some ways, the Scooter cycle is the best source we have for understanding the texture of life in Africatown in the early twentieth century, especially in the twenties and early thirties, when blues musicians crowded the juke joints, the surrounding forests were undisturbed, and the memory of the ship’s voyage was still palpable.

***

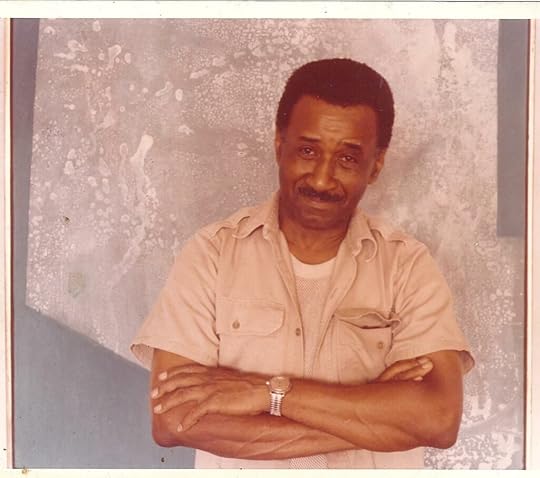

Albert Murray. Courtesy of the Murray Trust.

Scooter, the narrator and protagonist of all four novels, is obviously Murray’s alter ego—the author was straightforward about this in interviews. But the novels are more than autobiography, and Scooter is more than just a stand-in; he’s also a kind of epic hero and a trickster figure, not unlike Odysseus. Murray mixes these elements like a stride pianist, playing bass notes with one hand and chords with the other.

When Train Whistle Guitar begins, Scooter seems to be no older than ten, though he’s vague about these kinds of details. He and his best friend, Little Buddy Marshall, spend their free time traipsing around the woods and hanging out at Papa Gumbo Willie McWorthy’s barbershop.

Scooter’s family lives in a shotgun house on Dodge Mill Road, not far from Meaher’s Hummock—where Timothy Meaher, the business magnate who chartered the Clotilda voyage in 1860, was rumored to have lived. (The name “Meaher’s Hummock” is not Murray’s invention; it comes from Mobile County’s actual history. But a reader could be forgiven for thinking it’s a conscious echo of Sutpen’s Hundred, the name of the plantation belonging to William Faulkner’s most famous antagonist.) Scooter’s section of town is also home to an oil refinery and has taken on the name Gasoline Point. Train tracks border it on the east and west, and some of Scooter’s earliest memories are of hearing the rumble of the trains. He also tells us he learned to measure time by the whistles at the nearby sawmills long before he could read a clock.

Still, an element of wilderness remains intact. Our narrator is never more lyrical than when he’s depicting these rural-industrial landscapes. Take this passage from Train Whistle Guitar, where Scooter describes hopping onto a boxcar:

Then it was stopping and we were ready and we climbed over the side and came down the ladder and struck out forward. We were still in the bayou country, and beyond the train-smell there was the sour-sweet snakey smell of the swampland. We were running on slag and cinders again then and with the train quiet and waiting for Number Four you could hear the double crunching of our brogans echoing through the waterlogged moss-draped cypresses.

Up the Mobile River, north of Buckshaw Road, is the shipwreck that everyone believes is the remains of the Clotilda—or the Flotilla, or the Crowtillie, in neighborhood parlance. (Then, this was lore; now, the ship’s wreckage has been definitively identified—it seems the neighbors were right all along.) To the west of where Scooter lives, across from the AT&N railroad, is African Hill. By Scooter’s teens, most of the West Africans who once lived there have passed away, but Unka JoJo remains fairly spry. He tolls the bell every Sunday at African Hill Baptist Church and oversees the church’s cemetery. Like Scooter, Unka JoJo is an archetype; he reflects tropes of coastal Black folklore, a subject Murray knew intimately. But it’s also likely that some of the details in the narrator’s descriptions—like Unka JoJo’s “stick tapping, dicty-rocking, one-step-drag foot, catch-up shuffle walk”—come directly from Murray’s actual childhood memories of Cudjo Lewis.

According to Scooter, Unka JoJo often refers to Alabama as Nineveh and says he was brought over in the belly of a whale. Scooter tells us that when he was younger, he misunderstood the metaphor. Not knowing any geography, he thought the word Africa was short for African Hill. He assumed the references to Jonah were akin to preachers “declaring that we were all the Children of Israel on our way out of the sojourn of bondage in Egyptland.” It wasn’t until Scooter had access to a globe, in school, that he realized the old man had actually been carried over from across the world—on a 45-day journey across the roiling Atlantic, chained to the floor with 109 other captives.

***

Perhaps the most vivid character in Train Whistle Guitar is Luzana Cholly, a blues guitarist and drifter who comes back to Gasoline Point whenever he has money for gambling. Scooter and Buddy adore him: with his stories about faraway towns, his “sporty limp walk,” his “smoke-blue” voice, his guitar strings that sound like train whistles. It’s Cholly’s example that inspires the boys to skip school and climb onto that freight train, and it’s Cholly himself who hauls them back home (“as if by the nape of the neck”).

When Cholly isn’t around, the boys often park themselves at the barbershop. The men there relate anecdotes about the brothels (“sporting houses”) in New Orleans and San Francisco, and about the pimps and sex workers in Paris’s Pigalle (“Pig Alley”). The men pretend to forget Scooter and Buddy are within earshot, but it’s tacitly understood that the boys are getting an education. The barbershop is also where Scooter starts to learn the finer points of racial and class hierarchies—in particular, the differences between “high yallers” (light-skinned people of mixed race) whose parents were also high yallers, and “brand new mulattoes.”

There is also the air of latent, and sometimes outright, violence in this adult world. Hurston hinted at the dangers of Africatown in the later chapters of Barracoon. One of Cudjo’s sons was sent to prison for homicide, and after his sentence was commuted, he was murdered in front of a grocery store. Another boy in the family was decapitated by a train. The Scooter novels have echoes of these events. In one passage, a man named Beau Beau Weaver leaves the barbershop, and less than an hour later the boys hear someone screaming down the road. When they arrive, Weaver is lying in a puddle of blood, wearing only his underwear, with stab wounds all over his body. They learn that Weaver’s girlfriend caught him in another woman’s bedroom and murdered him in the yard.

In another scene, the boys are perched on a tree outside a nightclub, Joe Lockett’s-in-the-Bottom, watching the musicians perform on a Saturday night. A sheriff’s deputy comes to break up the party, and Stagolee Dupas, a piano player, refuses to leave. The deputy starts kicking Stagolee’s piano keys. The boys take off running when they see the deputy reach for his .38. The next day, the deputy’s body is found on the other side of town, slumped over the steering wheel of his car, with a bullet through his head. The Mobile Register reports that he was apparently killed by bootleggers.

***

For all of its rough-hewn qualities, the real-life Africatown, as of the twenties, was also home to one of the best African American schools on the Gulf Coast: the Mobile County Training School (MCTS), which was launched in 1910 in a collaboration between the shipmates’ descendants and other Black residents. Some of the most tender passages in the Scooter novels deal with this institution, which Murray attended from roughly 1923 to 1935. (In Scooter’s narration, it’s barely fictionalized at all—it shares the same name and resembles the real MCTS in almost every way.)

For most of Murray’s time as a student, a man named Benjamin Baker was the principal. Baker—whom Murray recast as B. Franklin Fisher in his novels—was a strict disciplinarian; the rumor on campus was that he kept a pistol in his desktop drawer. But if he intimidated students, he also inspired them. He was worldly, a sharp dresser, and commanding public speaker. When Murray was in his sixties, he writes in The Magic Keys, he could still hear Baker’s voice, telling the students to “acquit yourselves in all of your undertakings that generations yet unborn will rise at the mention of your name and call you blesséd.” Under Baker’s leadership, every teacher at MCTS had a college degree, a situation practically unheard of at rural Black schools in the South at that time. Rarely has an educator taken more inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of a “talented tenth,” a coterie of exceptional Black men and women who could take responsibility for racial progress. Everything about the school was designed to identify the most promising students and cultivate them as leaders.

Even more important in Murray’s life was the teacher who became the basis for his character Miss Lexine Metcalf. Miss Metcalf was always on the lookout for outstanding young minds.Scooter fondly recalls showing up early for school on a Wednesday morning, so he could have the globe and maps to himself. When Miss Metcalf looked up from her desk and saw him, she said, “How conscientious you are, a young man with initiative, and why not, because who if not you.”

“Who if not you?”—it’s a phrase that recurs so many times throughout the novels, always from the mouth of Miss Metcalf, that it seems likely it was a direct quotation from Murray’s life. This question apparently propelled the author for years afterward. Who, after all, if not him, to write his American epic?

So much does Scooter thrill at hearing Miss Metcalf call him “my splendid young man”—as she often does when he answers a question correctly, or shows special initiative—that he starts making excuses not to play hooky. By high school (in an arc matching Murray’s own), it becomes clear that Scooter is the most promising student the neighborhood has ever produced. He received a scholarship to college. He never moves back to Gasoline Point, but figures like Luzana Cholly and Miss Metcalf loom large in his imagination, long after he is gone.

Africatown on Sunday, June 2, 2019, in Mobile, Ala. Photograph by Mike Kittrell.

***

It’s been ten years now since Murray died at his home in Harlem, catercorner from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He lived there for five decades, far longer than he’d been in Alabama or any other place. Little wonder that his name is often associated with New York.

As for his work, it’s likely his extensive writing on jazz and the blues, including the autobiography Count Basie (which he co-wrote), that gets the most attention now. His knowledge of jazz was truly encyclopedic; he co-founded Jazz at Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis. But to understand why he was so drawn to this kind of music as an art form, we need his fiction. Nothing but jazz and the blues captured so well the atmosphere of his old neighborhood: the overwhelming sorrow that emanated from figures like Unka JoJo, the worldliness and playfulness of the men he met at the barbershop, and the idealism of figures like Baker and Miss Metcalf.

This also speaks to his contribution to the literature on Africatown. If Hurston’s purpose, as she wrote in the Barracoon introduction, was to render a kind of anthropological report on Cudjo, to inquire about how the “Nigerian ‘heathen’” had “borne up under the process of civilization,” then it was Murray’s lot to write about the world that Cudjo and the other shipmates—along with their descendants, the American-born Blacks with whom the descendants integrated, and the power elites of Alabama who shaped the conditions of their lives—had collectively made.

Nick Tabor is a freelance journalist living in New York. His first book, America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created, was published in February. Kern M. Jackson is a folklorist and the director of the African American Studies Program at the University of Southern Alabama. He was the co-writer and a co-producer of the Netflix documentary Descendant.

April 21, 2023

Divorcée Fiction: On Ursula Parrott

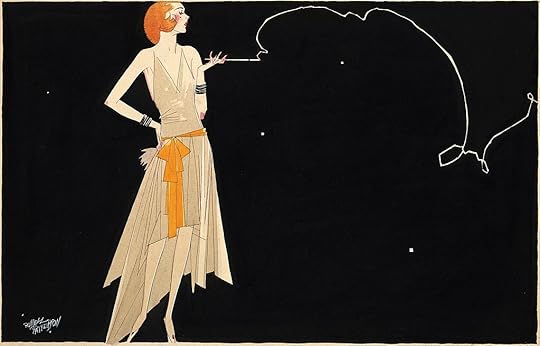

Russell Patterson, “Where there’s smoke there’s fire.” Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I’d never heard of Ursula Parrott when McNally Editions introduced me to Ex-Wife, the author’s 1929 novel about a young woman who suddenly finds herself suspended in the caliginous space between matrimony and divorce. The first thing I wondered was where it had been all my life. Ex-Wife rattles with ghosts and loss and lonely New York apartments, with men who change their minds and change them again, with people and places that assert their permanence by the very fact that they’re gone and they’re never coming back. Originally published anonymously, Ex-Wife stirred immediate controversy for Parrott’s frank depiction of her heroine, Patricia, a woman whose allure does not spare her from desertion after an open marriage proves to be an asymmetrical failure. Embarking on a marathon of alcoholic oblivion and a series of mostly joyless dips into the waters of sexual liberation, Patricia spends the book ricocheting between her fear of an abstract future and her fixation on a past that has been polished, gleaming from memory’s sleight of hand.

It’s been nearly a century since Ex-Wife had its flash of fame (the book sold more than one hundred thousand copies in its first year), and as progress has stripped divorce of its moral opprobrium, it has also swelled the ranks of us ex-wives. Folded in with Patricia’s descriptions of one-night stands and prohibition-busting binges are the kind of hollow distractions relatable to any of us who have ever wanted to forget: she buys clothes she can’t afford; she gets facials and has her hair done; she listens to songs on repeat while wearily wondering why heartache always seems to bookend love. My copy is riddled with exclamation marks and anecdotes that chart my own parallel romantic catastrophes, its paragraphs vandalized with highlighted passages and bracketed phrases. There is a sentence on the book’s first page that I outlined in black ink: “He grew tired of me;” it reads, “hunted about for reasons to justify his weariness; and found them.” The box that I have drawn around these words is a frame, I suppose; the kind that you find around a mirror.

For all its painful familiarity, it’s easy to get caught in the trap of Ex-Wife’s nostalgic charm; there are phonographs and jazz clubs and dresses from Vionnet; there are verboten cocktails and towering new buildings that reach toward a New York skyline so young that it still reveals its stars. If critics once took issue with the book’s treatment of abortion, adultery, and casual sex, contemporary analyses have too often remarked that Patricia’s world cannot help but show us its age. “Scandalous or sensational?” wrote one critic when the book was last reprinted, in 1989. “Times have changed.” Yes and no; released in the decade between two world wars, and just months before Black Tuesday turned boom to bust, Ex-Wife probes the violent uncertainty of a world locked in a perpetual state of becoming.

Lurching toward sexual revolution but still psychologically tethered to Victorian morality, women of Parrott’s generation found themselves caught in the free fall of collapsing convention. The seedy emotional texture of Ex-Wife’s Jazz Age debauchery reflected the panic felt by women across the country who had glimpsed freedom but remained ill-equipped to navigate its consequences. Almost immediately following the book’s publication, the press began a guessing game that sought to identify who was being shielded under its mantle of anonymity; was Ex-Wife a confession, a fantasy, or the indictment of a culture shifting too rapidly to acknowledge the inevitable casualties we leave in the wake of change? By August of 1929, conjecture had correctly zeroed in on Katherine Ursula Parrott (née Towle), a journalist and fashion writer who seemed to bear an uncanny resemblance to her bobbed and brushed heroine.

Considering the book in the context of what we now know about her life, one cannot put much stock in Parrott’s suggestion that Patricia was a composite figure. Instead, Ex-Wife seems to have been a place to record injuries too personal for her to claim as her own. Born in Boston to a physician father and a housewife mother, Parrott decamped to New York’s Greenwich Village shortly following her graduation from Radcliffe College in the early twenties. Her first marriage, to the journalist Lindesay Parrott Sr., ended in divorce in 1926, the year he discovered that the childless marriage he had insisted upon was not so childless after all. In 1924, Ursula had learned that she was pregnant and left the couple’s London home for Boston, where she gave birth to her only son before depositing him in the custody of her father and older sister. It was a secret that she managed to keep from Lindesay and their glamorous circle of friends for an astonishing two years. Marc Parrott, whose afterword concludes this book, would never have a relationship with his father. He was nearly seven years old when his mother finally acknowledged her maternity and assumed responsibility for his care. It was 1931 by then, and Ursula had become one of a handful of women who would find her fortune writing escapist romance tales under the pall of the Great Depression.

Marc Parrott’s recollections of his mother paint a vivid portrait of a spendthrift who often worked for seventy-two-hour stretches in order to meet the deadlines that would keep her (and her lovers) in furs. Parrott swanned through the thirties publishing short stories and serialized novels in women’s magazines, her name often mentioned alongside the Hollywood stars who were attached to her screenplays and cinematic adaptations. Although I never once found her son mentioned in the many news items devoted to her work and her persona, Parrott was occasionally found in the company of a pet poodle improbably named Ex-Wife; in more ways than one, it would seem, her greatest scandal was also her most stalwart companion.

Though Ex-Wife was initially framed as the writer’s endorsement of a dangerous new cultural model, Parrott herself was painfully aware of the double standard that continued to condemn “girls who do.” Divorced for a second time in 1932 and for a third five years after, the writer openly mused about her vulnerability in a world where marriage no longer insulated aging women from “man’s urge for variety.” Parrott called divorced women like her “Leftover Ladies,” a term that implies both surplus and rejection. Her abandoned woman is doomed to a battle that offers neither victory nor surrender. I think of Patricia examining the phantom lines that have begun to etch themselves across her face. I think of her cold creams and her lipsticks, of her awareness of a clock that never stops ticking. “The Leftover Lady is not free to get old,” Parrott wrote the winter after Ex-Wife came out, “for she has entered the competition, in her work and in her social life, with younger women. And that competition is merciless.”

By the early forties, as a serial divorcée who wrote stories with titles like “Love Comes but Once” and “Say Goodbye Again,” Parrott found herself a target of increasing mockery in the press. No longer young or glamorous enough to rate in the world she knew, her name would soon be attached to a series of scandals that could not be dismissed as the product of invention. In December of 1942, she was arrested and charged with helping an imprisoned soldier to escape from the military stockade in Miami Beach where he was being held on suspicion of trafficking narcotics. Michael Neely Bryan was a twenty-six-year-old jazz guitarist who had found some notoriety playing in Benny Goodman’s band before enlisting in the Army; the heady mixture of drugs and sex led to a high-profile 1944 trial and brought a swift conclusion to Parrott’s fourth and final marriage. Under headlines like “Novelist Seen Making Love in Army Stockade,” the writer was described as a matronly woman who, following a lurid encounter, drove through a checkpoint with her lover hidden in the back seat of her car. The two enjoyed one night of freedom at a hotel, where they registered under the name Artie Baker, then turned themselves in to the police, each making a tearful confession. “I looked at him and knew how badly he wanted to go to dinner,” Parrott said. “So I decided to take a chance for him.”

Though Parrott was ultimately acquitted, the trial marked her. No longer welcome in the pages of magazines that catered to “respectable” middle-class women, Parrott published her last story, “Let’s Just Marry,” in 1947, by which time she had completed twenty-two novels, fifty short stories, and four original film scripts, in addition to the eight novels that were adapted for the screen. She would surface in a fresh scandal in 1950, when she was arrested in Delaware after skipping out on a $255.20 bill following a six-month hotel stay. Friends said that she’d gone to Delaware to gather material for a new book, but would note that she’d spent much of her time walking her dog and very little of it in front of her typewriter. Newspapers suggested that she’d been undone by too much success, as though the tale she’d told two decades prior had finally proven to be a cautionary one. Parrott endured one final humiliation that definitively ended her career and any illusion she had of a return. In 1952, she was accused of stealing a thousand dollars’ worth of silverware from a friend who had allowed her to stay in his house under the premise that she needed a place to work on a new book. A warrant was issued for her arrest, and she spent the remaining five years of her life in hiding. She died, at the age of fifty-seven, in a charity ward.

It seems easy from here to understand that Parrott’s career as a writer was usurped by the drama of her scandals. Like many women whose early lives and work are defined by rebellion, Parrott’s indiscretions ceased to appeal once they were no longer deemed youthful ones. Her legacy endured one last condemnation when her work was framed by history as “women’s literature,” a term that was a tombstone in the days before it was understood as an industry. It became a ghost, like its author, neither married nor divorced, resigned to a perpetual now. Drifting around without a future, she drinks and shops, goes on dates, and wonders what else can possibly change in a world that no longer seems to have any rules. “Men used to buy me violets,” Patricia remarks with brutal resignation. “But now they buy me Scotch.”

Maybe I feel protective of Patricia because she feels so familiar to me—like proof that time doesn’t always change us in the ways that we would like to believe. If the book was once too far ahead of its day and later too far behind, it seems now somehow just right, as though we have rounded the circle again and finally found synchronicity. Wedged between Edith Wharton’s constrained society girls and the squandered glamour of Jean Rhys’s doomed wanderers, Ex-Wife was received by an interstitial America still negotiating who and what women were allowed to be. Once caught in a cultural riptide, the book now reads as a shockingly anticipatory account of what it means to want and what it means to be left; we live in a world now where most of us know the feeling of both. I think of the letter Patricia sent to a lover who could not love her back in the way that she needed him to, of the loneliness she felt when day turned to night and back again. “I shall be long dead,” it reads, “of waiting for a telegram saying you are coming home.”

Alissa Bennett’s essays and short fiction have appeared in Vogue, Ursula, and the New York Times. With Lena Dunham, Bennett cohosts the podcast The C-Word, a show that examines and dismantles the mythologies culture erects around public women. She is currently writing a film about the life of Edith Wharton.

From the foreword to Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife, to be reissued by McNally Editions in May.

April 20, 2023

The Birder

Bird lore, 1906. National Committee of Audobon Societies of America. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I knew a birder once. I liked him—it’s pointless to deny it and in any case I don’t think I can write about him without it being abundantly clear—though we redirected early enough that friendship seemed possible. For him it always was a friendship, anyway. Still, the birding excursion was definitely a date. Perhaps he was curious about whether he’d discover feelings for me among the pines—whether what psychologists call the misattribution of desire might be prompted by seeing a rare bird in my presence. We only saw regular birds, though: grackles, goldfinches, a great blue heron.

He was a birder but he was mostly a musician. I would have found it satisfying to discover that these were two sides of the same coin for him: it’s nice, after all, when people cohere, when you can discern a uniform purpose or a set of underlying values across their various pursuits. But the truth, really, is that people are more than one thing, and for most of his life, birds were an inconsequential if benign presence. It wasn’t until the 2020 lockdown that he discovered how far he was willing to go for their sake: a tundra swan in Pittsfield, a Pacific golden plover in Newburyport.

He was a musician first, though—a conductor. This meant he could replicate plaintive calls and fluttering warbles with a melodic accuracy far beyond the typical naturalist’s, and distinguishing between overlapping cries was hardly more difficult than finding the rogue soprano within a thirty-voice section. That comparison is mine, of course: conducting is not so much like birding, if you are really paying attention. Choir is about connection, he told me once—to the music, to other people. But you don’t need other people to walk around a lake in Woburn and check for sleeping owls. I just happened to be there.

He had one friend. This friend lived in Pennsylvania, but they had grown up together, and when he read a strange passage in a book or his car’s brakes were acting funny, that’s who he’d call. He had found that the ease and shared sense of humor born of twenty-five years’ friendship were not easily replicated—at least not without a similar temporal investment. Anyway, that was fine with him. If he had wanted more than one friend he would have networked more aggressively in kindergarten.

***

I didn’t know he was a birder when I met him. I knew he curved his wrists when he played the piano; I knew his voice was clear, his intonation precise. The first time we walked somewhere it was too dark for birds. But the second time there was an hour until sunset: he identified a red-tailed hawk and, at my request, a small bird I spotted flitting into a tree. (That’s a robin, he said, amused.) Once, we stopped to observe two northern flickers who were uncharacteristically content to putter about on the ground. When a house sparrow approached us at a picnic table, he held out his hand. We sat still and silent as the sparrow considered it, hopped forward, and then flew off to a nearby tree.

It was a summer when everything seemed to be going well for me. I only say “seemed” because they were the sort of things whose value is at least as much in the promise they suggest for the future as in the things themselves—small successes, indicating that my work might be worthwhile after all. I felt an energy spinning inside me. It reminded me of the way my high school choir director used to illustrate breath support, circling her fingers in front of her diaphragm like a motor. Spinning, spinning, she would say as we held a sustained note, her fingers moving with possibility and force.

The birder was part of this, for a little while—in that early stage where nothing is real yet but it seems that anything could be. It was like waiting for something to land, waiting for the moment when we would come to a first tentative answer: I know something about who you are, and something about who we will be to each other. Even after the landing, though—after the possibilities it foreclosed—I still felt the sense of spinning in myself. I spent mornings writing in coffee shops and afternoons reading in libraries.