The Paris Review's Blog, page 53

June 15, 2023

Playing Ball

Jamal with confetti. Rachel B. Glaser.

The collective dream is over. Squinting, we walk out of the playoffs and return to Life. Images linger—a giant holding a toddler in a storm of confetti. A shiny, exuberant, mantis-like man standing next to a trophy. The woman who sat courtside wearing red and white gowns. The inexplicable man-made-out-of-Sprite commercial. Duncan Robinson’s tough-guy face.

On Monday, after the great battle of Game 5, the Denver Nuggets won the NBA championship for the first time in franchise history. I was introduced to the on-court chemistry between Nuggets stars Nikola Jokić and Jamal Murray during the 2020 Western Conference Finals. Though they lost that series in five games to the Lakers (who would go on to win the championship after beating the Heat), they were great fun to watch. I found Murray’s smile infectious. He seemed unselfconscious and comfortable in his body. When he was having fun, I was having fun.

In 2021, Jokić received the first of two consecutive MVP awards. Right before the playoffs that year, Murray tore his ACL, missing the playoffs and the entire next season. Jokić carried the team without him, but in the 2022 playoffs, the Nuggets lost in the first round to the Golden State Warriors (who later went on to win the championship). While Sixers center Joel Embiid won this year’s MVP, most basketball fans believe Jokić is the better player. His performance in these Finals was sensational. His passes were gorgeous, his threes looked like afterthoughts. When the camera cut to him, he often seemed displeased. He was an unstoppable force, even when he wasn’t scoring. He made it look effortless. I thought of him as Paul Bunyan.

I liked whenever the broadcast cut to a room in Serbia, Jokić’s home country, where fans stayed up till dawn, watching the Nuggets game live. In the postgame interviews before the award ceremony, it was wonderful to see Jamal Murray’s teary-eyed smile as he spoke about the long journey coming back from his injury. And even a Heat fan could appreciate Jokić’s genuine disappointment upon learning that he’d have to attend a victory parade in Denver on Thursday when he was eager to fly home to Serbia to watch his horse, Dream Catcher, race on Sunday.

Though the series was tipping decisively toward Denver, Game 5 was close. Neither team ever led by more than ten points. Jokić’s early foul trouble gave the Heat some breathing room. Even small Heat leads felt luxurious to me and I tried to appreciate them, knowing they could be erased in mere seconds. Heat leader, Jimmy Butler had little swagger during the first three quarters, exhibiting his new tendency to drive to the basket and stall, as if afraid to shoot. It felt like he was unable to jump. My husband and I began calling him Brick-foot.

After witnessing Playoff Jimmy for much of the postseason, the mystery of his dead eyes and lack of energy gnawed at me during the last game. It looked like he had signed his soul to Ursula the sea-witch. Even when the Heat were ahead, part of me was troubled, trying to figure out what had happened to him. Probably his injured ankle from the Knicks series had gotten worse. Maybe it was fractured. Internet search results implied that his father might be sick.

For a brief stretch, Playoff Jimmy returned, hitting back-to-back threes, a jump shot, and scoring five points off free throws. The Heat led by one with less than two minutes to go, but a Bruce Brown layup put the Nuggets back in the lead. Then Jimmy drove to the basket, froze, and his pass to Max Strus was picked-off by Kentavious Caldwell-Pope. Caldwell-Pope was fouled and hit both free throws, sealing the Heat’s fate. Then Bruce Brown did the same, and Kyle Lowry was shaking hands with Nuggets players as the clock dwindled down its last seconds.

When I think of that last game, the most positive Heat memory I have is Bam Adebayo’s dazzling performance. Bam opened the game with a steal and a dunk, and he never relented. He looked lit up, activated. He played emphatically and with desire. To steal a term from the basketball writer and poet Ted Powers, Bam had the bodyjoy.

***

I used to experience bodyjoy when dancing, but these days it happens when I’m playing doubles tennis with my friends. When it’s good, nothing gives me more glee. It’s exhilarating to see a ball fly toward me and need to act fast to hit it. When else in life does something fly towards me? I jump through the air, my racket outstretched, unsure if I will reach it. When else do I jump through the air? Sometimes I totally miss, or it brushes the side of my racket and spins off at a funny angle. Or I hit it with gusto and it sails over the net and we all watch to see if it lands in bounds. It feels good to all be watching the same thing. The best is when we rally for so long the point seems to last forever. Our shots are solidly good and comically bad and by the time it ends we are laughing and have no idea what the score is.

Earlier this week, my husband read me the poem “Playing with the Children” by the unconventional eighteenth-century Japanese monk Ryōkan Taigu. In the poem, the speaker bounces a ball to some neighborhood children and they bounce it back, singing and playing. My favorite lines of the poem are: “Caught up in the excitement of the game / We forget completely about the time.”

People have been playing ball for thousands of years. Nausicaa was playing ball with her maidens when Odysseus first saw her in Homer’s The Odyssey. Balls connect children. They connect dogs and humans. Playing releases endorphins, which often leads to happiness. Taigu’s poem ends with: “Passersby turn and questions me:/ ‘Why are you carrying on like this?’/ I just shake my head without answering/ Even if I were able to say something/ how could I explain? / Do you really want to know the meaning of it all?/ This is it! / This is it! ”

Rachel B. Glaser is the author of the story collection Pee On Water, the novel Paulina & Fran, and two books of poetry.

June 14, 2023

Making of a Poem: Richie Hofmann on “Armed Cavalier”

A draft of the first two pages of “Armed Cavalier.” Courtesy of Richie Hofmann.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Richie Hofmann’s “ Armed Cavalier ” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 244.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

As is so often the case for me, the poem began as another poem entirely. I was working on a poetic sequence that interposed my translations of Michelangelo’s homoerotic sonnets with several short, original haiku-like poems inspired by Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids. Both artists were interested in beauty and torture. Mapplethorpe’s photographs are experiments in self-portraiture and bondage. In one of Michelangelo’s sonnets, the speaker confesses that, in order to be happy, he must be conquered and chained, a prisoner of an “armed cavalier” (the phrase puns on the name of the object of Michelangelo’s infatuation, Tommaso dei Cavalieri). Upon reading that phrase, I instantly wanted it to be the title for a new poem that would express the extremity of sexuality and the extremity of making art.

From the sonnets of Michelangelo, I wanted to import a kind of violence of rhetoric (not unlike the dramatic conceits we find again and again in Petrarch). The poems are so desperate. Their pain is sculptural. From the photographs of Mapplethorpe, I wanted to import a violence of image. And the sense that everything—flowers in a vase, classical sculpture, BDSM—is part of a landscape of embodied beauty. Ultimately, as I revised the poem, and reworked it into “Armed Cavalier,” I wanted to express the ferocity of feeling in both artists’ works, but without any overt ekphrastic framing.

Are there hard and easy poems?

Yes. I love the easy poems, poems that reveal themselves immediately, that feel heard and merely transcribed and not labored over thanklessly. It’s hard to love the hard poems back. I have often found, as in the case of this poem’s origin, that sometimes the best revision of a draft is the writing of a new poem.

Was “Armed Cavalier” hard or easy, then?

This was an easy one. As an exercise, I sometimes try to write in a sort of frenzy, to fight against my tendency toward elegance. Writing quickly, without pressure, allows me to encounter ideas and feelings I wouldn’t find acceptable or worthy or complete enough in my normal, judgmental mindset. I’m trying to let more of myself in to the poems—more ugliness, more hunger, more insight. This is how I drafted “Armed Cavalier.” I knew early on that it would be an important poem for me.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidants?

I show most of my drafts to other poets. Soon after I drafted this poem, I called my poet friend Christian Gullette and he helped me edit it into its final form: cutting some “tourists,” for instance, and getting right to the “galleries.” Later in the process, I called Kara van de Graaf and we agonized over two small but essential decisions: should a line read “I don’t want to” or “but I won’t”? And should the final line—with attention to grammar but also to voice and music—read “I sleep only in this bed now” or “I only sleep in this bed now”? Thank God for friends who care about this stuff!

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

A poem feels finished when I can’t enter it again. Everything falls into place, each line feels balanced and complete, the shifts between lines and sentences feel shocking but also permanent and incapable of change. This poem is finished. I have to make something new. I have to be a different poet.

Michelangelo, The Punishment of Tityus, 1532. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Richie Hofmann is the author of two books of poems, A Hundred Lovers and Second Empire. His poetry has appeared recently in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, Poetry, and The Yale Review, and has been honored with the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and the Wallace Stegner Fellowship.

June 13, 2023

War Diary

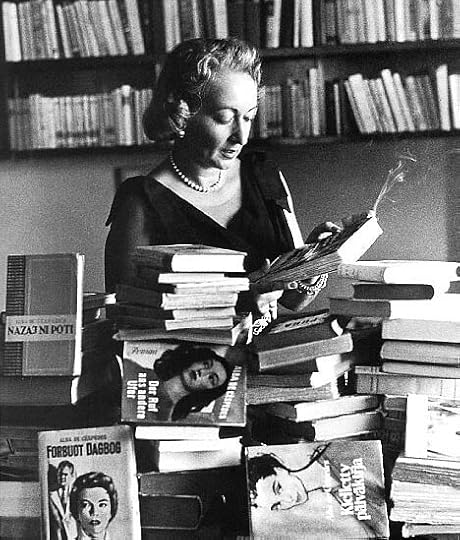

Alba de Céspedes, 1965. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On September 8, 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies, and the Germans, who had already occupied the north of Italy, immediately moved to take over the rest of the country. Just days later, they invaded Rome. Meanwhile, British and American forces had landed in the south and were slowly moving northward.

The writer Alba de Céspedes and her companion (and later her husband), Franco Bounous, were living in Rome. De Céspedes had been jailed briefly by Mussolini for antifascist activities; Bounous was a diplomat and did not want to collaborate with the Germans. As conditions in the city worsened, becoming more chaotic and more dangerous, de Céspedes and Bounous decided to leave. On September 23, “secretly, at night,” they departed, “each with a suitcase,” de Céspedes wrote to her mother, “thinking we’d be gone a few days, that Rome would soon be liberated.” They escaped to a village in Abruzzo, east of the city, where they expected they would be able to wait in tranquility. But the Germans showed up, and they fled again, to a tiny village in the mountains nearby, Torricella Peligna.

This diary recounts the days between October 18, when they had to flee Torricella and go into hiding in the woods, and November 19, when they decided to try to get through the German lines to reach the safety of the Allied-occupied zone. De Céspedes later wrote, “Life had gradually become more unbearable, the Germans were coming at night, too. So we decided to risk it all and cross the lines, reaching the Anglo-American troops. And safety. We did that, walking at night, November 20” Guided by a local farmer, Fioravante, they managed to cross the Sangro river, which marked the German front line, and arrive in the Allied zone. From there they were taken in a farm cart to Bari, where de Céspedes began broadcasting for the antifascist station Radio Bari. Eventually she and Bounous moved to Naples and, finally, returned to Rome, after it had been liberated by the Allies in June of 1944.

—Ann Goldstein, translator

October 18, 1943

We were still asleep this morning, sheltering in the dusty, desolate tax office in Torricella, when we heard frantic knocking at the door. The pale face of Carmela, the girl from downstairs, appeared, animated by a new fear: “Quick, get out right away, the Germans have surrounded Lama dei Peligni and taken the men, all of them. Now they’re on their way up here.” We dressed in a few minutes, maybe three or four, not even taking the time to grab some clothes, and we were gone, Franco, Aldo, and I, rushing down the stairs. Someone was already shouting, “Here they are, you can hear the truck.” We hurried along narrow stony streets, running amid other people running, me wanting to stop and catch my breath, then thinking, I have to make it, I don’t want to leave the others, and I kept running, with a stitch in my side. Some young people were fleeing with their few possessions salvaged in a basket, and we all looked to see if the white ribbon of the main road was stained with the yellow of German cars. Ears strained to the faintest hum. Squatting below the level of the main road, we let some armored vehicles go by, then we ran, crossing it quickly, almost in a leap, and were finally on a path through the fields. Aldo said: “We have to get to the Defensa woods, no one will come and look for us over there.” In less than three hours we had found shelter on Trecolori’s farm, an isolated place at the edge of the big woods. Trecolori is a sly, monkeyish old farmer who lived in Pennsylvania for twelve years. He didn’t have room for us; already, there were numerous relatives around the hearth who had come from nearby villages to escape the raids, some sitting on sacks of flour, others crowded on the floor, looking at us silently. “You can sleep in a stable, five hundred meters from here. Anyway, it’s just for one night.”

We’ve been here now for five days. We’re sleeping in a hut that’s half stable, half woodshed, with straw pallets on the ground, and at night we light a fire. A broken-down door barely hides a view of the sky. It’s very cold. Each of us sleeps wrapped in a blanket: even our heads are wrapped, to warm ourselves with our breath. Seven men are sheltered in this stable; I’m wearing pants and live with them like a comrade.

We’re attuned to the sound of a footstep, a rustling. If there’s danger, if the Germans come down to raid the farms, someone—there’s always a lookout—sends an agreed-on whistle, a word. The signal of alarm spreads instantly from shelter to shelter, all the way to us, here at the edge of the woods. Immediately, tumbling through the plowed fields, we reach the stream, cross it, go up into the woods, hide in the thicket of trees and brush. We stay there, silent, motionless, sometimes in the rain, for hours. I don’t know how we’ll manage if the cold gets worse. We don’t have coats, not even a wool sweater. The English are still at Termoli: the battle is really fierce. Sometimes, around sunset, Allied prisoners headed for the Sangro river pass through the countryside like shadows. They want to reach their lines, but it’s hard. We stop them, hoping for news. They’re surprised to find down here, in the middle of nowhere, someone who speaks their language, knows their countries. Then we follow them with our eyes as they grow distant, and it’s as if through them we were sending out a cry for help: Come! Free us! We have no comfort other than the news brought by mouth from Torricella, where someone hiding in a cellar listens to Radio London. Meanwhile the season is advancing—we’ll have to build a shelter in the woods if we’re going to spend many hours in the rain.

October 19, 1943

Peppino arrived last night running, terrified. He’d spent eight hours in a woodshed, scarcely breathing. The Germans showed up without warning in Torricella yesterday morning: they blocked the streets, seized all the men and loaded them on a truck, and drove off. Donato Porreca, the owner of the shop, tried to flee, but a machine-gun volley lashed him in the side, and he was killed instantly. Peppino described the agony of the women screaming as the truck left. Meanwhile the death bell tolled for poor Donato.

October 20, 1943

This morning we were all up at four, ready to flee. False alarm: it was a French prisoner passing through the fields, and a farmer fired in the air. Last night, while we were gathered around the fire at Trecolori’s farm, we heard shots nearby and women’s voices crying for help. A farmer arrived, running, with the message: it’s the Germans, they’re shooting. With Aldo and Franco, I rushed down the slope above the stream, the branches and briars dense, almost impenetrable. Behind us a woman’s crying could be heard, the lament of Sofia who was calling her husband. Around us other refugees were fleeing; a Russian shouted, “Where are you? Help me,” and risked getting us all discovered. I could have killed him to shut him up. Down the steep embankment to the stream, grabbing a tree trunk, scratched by thorns, through the creaking thicket of branches. We exchanged words muffled by fear: Off with the raincoats, they’re too pale, they can be seen in the shadows. Like blind men we went into the stream, the freezing water came to our knees; we crawled up the wooded embankment opposite on all fours. In the midst of the terrible fear I remembered stories I read as a child, the jungle stories. At every step you had to extricate your foot from the tangled vegetation of the undergrowth, make a pathway with your hands, eyes closed so that the thorns wouldn’t wound them. Franco’s eyes were protected by his glasses. At times I had a suspicion that we were doing all this for fun. I, Alba, couldn’t truly be in such a grave situation, on the point of being captured by German soldiers, shot, killed. The entire experience seemed stronger than me, than my capacity to endure. Whereas at other times, in the silent, insidious darkness, the danger seemed to me so close that there was no escape, no possibility of flight. It was over, we’d been captured. The grim, distant barking of a dog made my distress more acute. And over all was the humiliation of having to flee like a criminal, sampling the life of a murderer or thief, though I had committed no crime, only dreamed that my own country could be free and civilized.

Some two hours in the woods. Cold. Occasionally we’d start moving again, climbing uphill to get warm. All around were the innumerable sounds of the nocturnal life of the forest: the voice of an owl, a slow rustling in the dry leaves, a darting among the branches. The three of us sitting on the ground waiting. Finally we heard a distant, low whistle: the whistle of friends. It was as precious as suddenly recovering the taste of life.

October 21, 1943

Nothing new. Inert and discouraging wait. The English don’t arrive; according to the news from Torricella they’re in Istonio. Mariuccia, a sly, skinny woman of ninety, serves as a link between the town and us. She brings the news in a note written by Don Peppe, the notary in Torricella, and hidden in her corset or her bun. A lot of airplane activity. We’re starting to wear holes in our woolen socks, the only ones we have. Also the salt is gone. This morning, after long days, we went to wash in the brook. In the afternoon we studied positions for a shelter in the woods, choosing the most secure. The trees were illuminated by the setting sun, the fallen leaves were red and shiny. Clusters of pale cyclamens emerged from under the tufts of broom. I would have liked to make a bouquet, as I used to do in the woods in Ariccia as a child, but it seemed frivolous to be picking flowers while we were trying to choose the place for a shelter to save our lives. Franco and the others strained their ears at the crackle of a machine gun that could be heard coming from Montenerodomo, at the edge of the woods.

October 22, 1943

I’m writing on the rocks by the brook. We came to wash. Aldo and Trecolori are digging a shelter under a large boulder on the shore. We’re tired, nervous, mute. Sometimes we enter the state of mind of the criminal who can’t hold out any longer and hands himself over to the law. Peppino said I’m risking everything, but I want to go home, to San Vito. We take out our bad mood on the lack of food and the wretched bedding. If not for the ineffable solace of nature, life would be without dreams or joy, entirely harsh, to be endured, to be lived faithfully, with no escape.

I feel humiliated waiting to be freed by the English. Every day we wonder, almost impatiently, scanning the outlines of the hills: When are they coming? Reduced to waiting for the joyous arrival of foreign soldiers!

Later

I reread what I wrote above. It seems to me that I’m still bound to petty, limited principles. The fact that they inhabit a country divided from mine by a mountain range or the sea, that they speak a different language, shouldn’t create an obstacle between us. A common civilization, a Christian solidarity, should bind peoples: with these considerations it becomes easy for me to accept their help, wait for their arrival. And yet, in spite of myself, in this relentless struggle, through this consuming defense of ourselves, I sense a struggle for my country, a consuming defense of my country, this, Italy, this and no other, the Italy that made my heart beat faster when as a child I merely heard the name: this is what I defend. These fields, these trees, these farms, these backward villages of a poor and defeated country are mine and I defend them as I can with my hatred, my flight, my torn socks, the darkness that frightens me. I left Rome with the sole desire to preserve my freedom, moving abruptly from my pink room on Via Duse to the sight of burned-down houses, caves populated by refugees for whom life is reduced to eating and sleeping, and now I resist precisely to defend this poverty of ours, this pain of being humans who are banished, hunted, humiliated, and defeated.

October 24, 1943

Nothing reassuring for two days. We’re increasingly ragged, increasingly dirty. It’s hard to glimpse the possibility of holding out still longer without being able to change, always sleeping in our clothes, so tired, so nervous. In the evening a mortal sadness takes possession of us: around five, when it’s still day for those who live in cities, who can flick a switch, turn on the lights, pick up a book. Live. It’s night for us, forced to the weak light of the hearth or to walking silently in the dark. The days are uncertain, tedious, humiliating. They die leaving each of us with a more profound weariness and no hope for the new day. In the depths of this dark valley no one helps us or enlightens us. Every bush is a threatening shadow, the donkey chomping in the haystack is the sound of hobnailed boots on the path. It’s the safest time: at night the Germans are unlikely to risk the woods, they’re afraid of ambushes. And yet an invincible terror overwhelms us at that hour. Franco and I walk along the rocky path. We try to rediscover strength in ourselves. Instead we’re frail, a negative thought is enough to crush us. We’re motionless for hours, sitting on the ground, fascinated by the flashes from the artillery firing behind the mountains. Every day, we talk for hours about crossing the lines. Franco says: how is it possible with a woman? And Edoardo looks at Emilia—they often come to see us from the farm where they’ve found shelter—and repeats: it’s not possible. That humiliates me, depresses me. I’m sure I, too, would make it; like theirs, my shoes are heavy, hiking shoes. I proposed to Emilia that we let them go alone, and then follow, the two of us, leaving an hour later, without their knowing.

Three women stopped by the stable. One was carrying a sick child in a basket on her head. A stomach abscess. She had heard that there was a doctor among us, they had walked kilometers, hoping he could operate. But Mario wasn’t here, he was out looking for food. And, besides, he couldn’t operate, he has only a pocketknife. They waited for him silently, their faces already grim. Mario said later that the child will die.

October 25, 1943

Franco had a very high fever yesterday. I gave him my straw pallet. We have no more candles, no matches. After sunset we move around the stable groping, as if we were blind. The dark is a nightmare, it seizes us by the throat. And the woods, with the trees losing their leaves, no longer seems to want to offer us protection. We have nothing, we can have nothing. Even an old shepherd is terrified and doesn’t dare go to Torricella for medicine.

Later

I have a map of the area, and everyone comes to us to consult it. On the map, inset between three small circles that mark the towns of Buonanotte, Torricella, and Montenerodomo, and in a darker color since we’re at an altitude of a thousand meters, you can see the position of these woods. Three small Abruzzo villages whose existence I didn’t even suspect, and which I would never have known if this disaster hadn’t befallen Italy. Now, however, I hear their names from morning to night, and the contours of these villages on the distant horizon have become as familiar to me as the faces of my father and mother. My life now exists in this delicate tangle of lines that the area of a fingernail could cover. My past, my fairy-tale childhood, my work, my travels, the people I’ve met—all that I’ve lived, in short, was to lead me here, to these woods. And my future, my safety are entrusted to these trees. My life is entrusted to the leaves that don’t drop off, to the snow that doesn’t fall. Books read, faithful friends are no longer of use to me, everything is now contained within the woods called la Defensa. Defensa in Spanish means “defended.” On the big map of the world these woods are a speck of dust and I am an infinitesimal part of it, and yet it’s here that everything is decided for me.

No one knows that in this tangle of lines, in these woods in Abruzzo, there’s a woman named Alba, and that she’s still young and likes the colors of the sky and the woods, likes life immensely and still has many things to do and say, and yet tomorrow she may no longer exist.

No one knows anything. My mother is in Havana, and outside the door of our house there’s a big palm tree, my friend. My mother thinks I’m in Rome and maybe she goes out and talks to her friends while I’m lying on the ground in the mud, hidden behind a bush, or I’m poking at the fire, blowing hard, and Franco is sick, shivering, in the grip of malaria.

Oh, I wish the door would open now, and someone would come in and say the war is over, no one will be killed anymore, we can go out, speak aloud, be seen, be free.

October 26, 1943

I can barely write in this shoddy, beat-up notebook. I have to take it with me every time there’s an alarm, it’s unwise to leave it in the stable. Tonight it was crushed between two plants near the cave dug by Trecolori. Yesterday evening, at six, the alarm. We fled to that cave, Franco and I alone, with the blankets over our shoulders. We were buried in the darkness. Franco had a very high fever, he was trembling as he lay in the gloom of the cave: a profound and tenacious dampness rose from the earth despite the blankets. No sound except the tumbling of the stream, which at first seemed to us a hoarse drumroll. We went back up after two hours. The Germans are getting closer. The circle tightens. This morning we were in alarm for three hours, first in the cave, then in the woods. We’re reduced to nearly nothing. Franco has a fever again. They pass

October 28, 1943

The preceding journal entry was interrupted because of an alarm. The Germans were very close by. We fled into the woods, Franco feverish and extremely weak. We have no water, our underwear is torn, we have to jealously conserve the fire under the ashes because we have no more matches to light it again. The men are exasperated by the lack of cigarettes. Carmine, Trecolori’s son, got hold of some tobacco leaves. They crush them and then roll the tobacco in the German-language leaflets that the RAF pilots drop over the lines. We’re exhausted. The English are still distant, five kilometers from Vasto, it’s said. Meanwhile the Germans are sacking the villages all around, tonight it was Montenerodomo’s turn. Life has never been so serious for me. Only there’s a great sweetness in the innocent candor of Aldo, who regrets not having a cake today, for his birthday. Soon even the comfort of writing these notes will end; I have no idea how to get another notebook.

I’m writing on my knees while the others argue nervously and irritably about politics. The Poles came, too, three young students who for four years have been fleeing from town to town. We built two sawhorses from logs with the bark stripped off to sit on in the stable. Around sunset, people from all the shelters in the woods come to our hut, drawn by the warmth of the fire. There are Romanians, Russians, Yugoslavs, a German Jew, some former political internees. All bound by a human solidarity that abolishes borders and passports. We don’t ask names or political stripes, we only read in the eyes of the others the need for help in getting through these brutal hours of life. Here, in this remote stable, at an altitude of a thousand meters, it seems to me that the Italy we wanted is truly being born. My heart races at this sudden discovery. Here, right here, in this stable, worn out, hungry, with nothing, nothing that resembles civilized life, we begin again to live in a civilized manner. The Russian talks about his country, the Poles about their literature, the Jew no longer stares at the top of the hill with tormented eyes to see if the Germans are descending from there.

They go on talking. I like their voices, the hesitant Italian, the open discussions. Dear sweet country of mine.

October 30, 1943

Tonight a Sicilian student showed up, a thin young man with a boundless gaze behind large glasses. Voice and accent of Rodolfo. He was walking from Mantua, a month on the road, sleeping in haystacks, asking for a piece of bread at farmhouse doors. He stopped with us and looked in the direction of the Sangro, which he intended to cross under artillery fire. When I offered him soup he would have liked to devour it, but mastered himself to make the unusual pleasure last as long as possible. I invited him to stay; he hesitated a moment. He was exhausted, nearly ill, his bare, skinny legs of a livid white. “How much suffering,” he said, “for all of us, because of a single man.” There was no hatred in his voice, only the desolate, tortured resignation of the meek. He said goodbye to me soon afterward: having overcome his brief hesitation, he had decided to leave, heading straight to the valley of Buonanotte and the lines. He studied the map for a long time, as if he were reading a death sentence. Then he said: “If I live, I’ll send you a card, give me your address in Rome.” And he headed down the slope, leaning on his tall stick and moving unsteadily in the mud, his legs sticking out thin and pale from under his patched overcoat. I fear I will never get that card.

November 2, 1943

Days ago, in the devastation of Montenerodomo, the Germans destroyed Domenico’s shop—the sergeant whose shelter is a dark, smoky cave a few hundred meters from here, and who sometimes prepares us a disgusting piece of mutton burned on the hearth. He has a tubercular wife and a son covered with a repulsive rash. Today, while he was hiding with us in the woods, the Germans descended on his cave and carried off the pig, on a leash, like a dog. When we returned and Domenico found out that the pig was no longer there, he asked Annuccia for a flask of must and got drunk. Drunk, he wept and sobbed, rolling on the ground in the cow manure and calling his pig in a loud voice, like a beloved person. He has nothing now. He fought for many years of war: he was wounded, and is half-blind.

Now, while I’m writing, Sofia and Armida—Trecolori’s daughters—in red dresses lighted up by the sun are digging a pit behind the house to hide the linens. They work briskly, without grieving, as if they were turning over the earth for sowing. They protect themselves from the war, as from a natural phenomenon, cyclone or hail. They don’t know the reasons for the war, where Germany is, what Great Britain is. Here, even in peacetime, there were no newspapers, and, besides, they wouldn’t be able to read them. Mail was distributed once a week. One day the card that called up Domenico arrived. They know nothing, they aren’t to blame. And yet it’s they who pay, with burned-down houses, stolen animals. They stare at the Germans in astonishment, with no understanding of why they are doing them all this harm. The Italian people of the mountains, of the remote hamlets, of the isolated villages aren’t to blame. It’s we, we who are guilty. And they welcome us, shelter us, we who have been, first and foremost, their enemy.

November 4, 1943

I’m worried about Rome, my son, Aunt Maria, my house. Countless objects that have followed me everywhere with their stories, their marks: a Madonna bought on the Lungarno, a book found in Venice. I’m living entirely in the past these days: Havana, Paris, Papa. I have a tremendous desire to return to being young and happy, not to hear talk of wars, soldiers, not to be afraid anymore. Tomorrow the young Poles will leave with Peppino to cross the lines. Peppino made the decision, but now he’s depressed, drawn to and dismayed by the void he’s casting himself into. This morning Mario brought good news from his rounds: the German retreat is supposedly imminent. I don’t believe it. I no longer believe anything.

November 5, 1943

I want to write a long story that tells about these woods. Which appeared friendly at first: our salvation, our escape. And now they’re our nightmare. They’ve become the mirror of our consciousness. To save ourselves we have to flee, at risk of our lives win the right to peace and freedom. We have no one to believe in, no one to follow. All Italy has taken refuge in us: each of us, inside, is all that remains of our country. A farmer promised me a notebook. The Poles are no longer leaving: the news arrived that you can’t get through the lines. In the midst of these changing events the woods are unmoving. Oh, I’ve found the story of the woods!

November 11, 1943

Antonio Piccone Stella, who is living on the Tre Confini farm, less than an hour from here, came to see me. He, too, wants to cross the lines. How distant literature is. We talk only about this now; we’re impatient, we can’t endure the waiting. I want to go, too. Everyone says: She won’t make it. And I foam with rage: I’ve climbed so many mountains, to so many mountain huts. I’m not afraid. Better to die here on the lines, better to be carried away by the Sangro. Emilia, too, has said she will follow her husband. Every day we calculate kilometers, trace routes on the map. The Sangro is swollen with the rains. You have to know where the banks aren’t mined.

Later

They’ve cleared out Pennadomo and Fallascoso. The towns are burning, the odor of ash reaches us on the cold breath of the wind. The natural Germanic fury is unleashed everywhere. My thoughts turn constantly to America. It’s as if emerging from these oppressive and treacherous woods I had no escape but a harbor in America, the white harbor of Havana.

November 13, 1943

There’s a white ribbon on the door of Trecolori’s farmhouse. Anna Maria was born, daughter of refugees. Around us the towns are burning, in Annuccia’s house they are wailing and weeping for the women driven out of Pennadomo. And this child is born. Emilia and Edoardo wanted to flee this morning, then they gave up. One can’t go, when everything around is so beautiful, when a new life opens up, with its endowment of dreams and hopes, when the maples in the woods are bright red, and the fields, with the shoots poking up, are green as in spring. One can’t say: Tomorrow, perhaps, I will no longer see all this.

November 15, 1943

Every attempt to write is interrupted by the alarm.

We have no more strength. It’s cold, pouring rain, the slopes are muddy, slippery, going down to Trecolori’s farmhouse is an undertaking, we fall down and get up, discouraged. A little after four, we’re prisoners of the darkness, blind, shadows. With the darkness comes an intense depression that thickens the air, like a suffocating fog. We’re silent, humiliated around the hearth. What time is it? Always too early to eat, too early to throw ourselves clothed on our pallets. My clothes are a perfect imitation of a tramp’s. I have no underwear or socks to change; my raincoat, which still serves as a pillow, is black with dirt, mud, grime. Will I ever have another? Will I find my house again? And my books? And our life?

November 17, 1943

News arrived of a massacre at S. Agata. The Germans entered a farmhouse suddenly, seized the men, threw them against a haystack, mowed them down with machine guns. The women, all, were spared.

This possibility of being saved owing to the sole fact of being a woman humiliates me deeply. It seems to me that my solidarity with Franco, and our other comrades, can’t be complete, since, at the last moment, I would be unable to sustain it. When we flee all together or are crouching down, holding our breath, it seems to me that mine is an easy game. I’ve decided, if they capture us, to shout, ceaselessly, “Down with Germany, long live Italy!” so that they don’t take pity on me.

November 18, 1943

We can’t go on. We have to decide. From this morning at seven we were in the woods, now bare of leaves, lying on the ground under the blankets. We returned to the stable, then went up to Annuccia’s to beg from her generosity a bit of polenta, but soon afterward we had to flee again, still hungry. The Germans discovered our shelter. They entered the stable, dug around in the straw, were made suspicious by those pallets, and remained in ambush nearby, hoping to surprise us like animals returning to their den. We saw them from the woods; some of us were armed, it would have been easy to fire, we saw them very clearly, we saw their legs opening like scissors, they were an easy target. We couldn’t shoot; if we had, after two hours other Germans would have descended to burn and destroy all the farms within a radius of two or three kilometers. We wouldn’t have run any risk: we could easily move to the opposite side of the woods, camp there. But the farmers, those who have welcomed and protected us, would pay for us, as has happened elsewhere. The Germans would burn the farmhouses, kill even the women. We could only spy on them with hatred, the whole wood was still and silent, an immense eye that looked at them with hatred.

Tonight we organized watches: every two hours two of us went up to the ridge of the farmhouse, as sentries, protecting the sleep of the others. But, just the same, the others can’t rest. One thinks: and what if they fall asleep? Or don’t see them? I had my watch with Franco and Edoardo, from two to four, it was a white night, foggy. Now Corrado and Aldo are out looking around. Franco gave up making himself a cigarette: he can’t do it, there’s too little paper. I have to protect this notebook from the smokers. We have nothing anymore, the woods are wet from the rain, we can’t light a fire, there’s only a lot of bitter smoke in the stable. We’ve even lost our only treasure, the pocketknife. I have to endure, continue to be strong. We’re cold. Trecolori looked at the sky and said that in two days we’ll have snow: so the Germans will follow our tracks. Edoardo and Franco want to cross the lines. They still seem uncertain when they look at us, at Emilia and me, but I know we’ll go. We have to go. Not to escape the Germans, not to reach the English: to win by ourselves, across the lines, over the torrential stream, the right to be free. Tomorrow Piccone, who wants to cross with us, will come. Edoardo and Franco went to talk to Fioravante, who will guide us for a stretch. Now they’re studying the map, they repeat yet again the usual names: Monte Pallano, Colle dello Zingaro, and then that bitter and fascinating word Sangro, Sangro, Sangro … Then they say: Trenches positions mined fields—they trace the route. And I who have always hated these words, always hated war, never understood volunteers, heroes, now I, too, have been won over by this spirit, my only desire is to go toward all this. Maybe I won’t get there, won’t write anything else. But we have to try.

November 19, 1943

A few seconds to write. We’re leaving to cross the lines. Franco, Emilia, and Edoardo are ready in front of Trecolori’s farmhouse, I went back to the stable on the pretext of getting the canteen I’d forgotten but in reality to be alone, to write a few words. I’m wearing pants and my raincoat and, on top, pulled over my head through a hole made in the center, a dark blanket that will serve to camouflage me. The edges are pinned with two safety pins. It’s really heavy, I don’t know how I’ll walk like this. Over my shoulder I have another blanket rolled up the way soldiers do.

All our friends have come down from the shelters to say goodbye. Tonino, nerves shattered, weeps uncontrollably leaning against a tree, the Russian rolls on the ground in pain from his ulcer. We shake hands, kiss rough cheeks. Worried, moved, they look at us as if seeing us for the last time. This morning we, too, were nervous, silent, we didn’t speak to each other, we four, in order not to exchange impressions about the decision we’d made. And now instead I feel light, light, smiling, as if I were leaving on a festive journey. There’s a little sun, in the doorway the cherry tree positions itself lightly, as in an arabesque. I wrote something on the wall of the stable with tincture of iodine, I wanted to be alone for that, too. I don’t know what, exactly, “the lines” are, I’m afraid only of setting off the diabolical mechanism of a mine with my own foot. I have money hidden in my breast, I’ll also hide the notebook. I want to write this, very clearly: I’m not afraid, I feel only this enormous, perhaps nervous joy. And the sense of playing a trick on the Germans, by fleeing, the desire not to be found here by the English, four healthy Italians, waiting idly. I feel only hatred and joy. If we were to die, our companions in the woods wouldn’t even know it right away. My son, my aunt, would continue to live as if I were still alive. My mother—who can say when she would find out.

The sky is getting foggy. It’s three thirty. Fioravante said that before dawn we should be at the Sangro.

Alba de Céspedes (1911-1997) was an Italian-feminist writer whose novel Forbidden Notebook , was published earlier this year by Astra House, in a new translation by Ann Goldstein and with a foreword by Jhumpa Lahiri. De Céspedes’ experiences of the war as described in these diary pages had a profound influence on the writing of Her Side of the Story, which will be published in November 2023, in a new translation by Jill Foulston and with an afterword by Elena Ferrante.

June 12, 2023

The Bible and Poetry

Initial S: A Monk Praying in the Water, Getty Center. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

We do not read the Bible as it is meant to be read. Theology always risks leading us astray by elaborating its own discourse, with the biblical texts merely as a point of departure. The presence of poetry in the Bible is the key to a more pertinent and more faithful reading.

There are many poems found in the Bible. We know this, vaguely and without giving it too much thought, but shouldn’t we be rather astonished by the role of poetry in a collection of books with such a pressing and salutary Word to express? And shouldn’t we ask ourselves if the presence of this writing—so much more self-conscious and desirous than is prose of a form it can make vibrate—affects the biblical “message” and changes its nature?

It is unsurprising that the Psalms are poems, given their liturgical purpose and the abyss of individual and collective emotion that they explore. At the heart of the Bible and yet also apart from it, they lay out, we might suppose, for both the individual and the community, the lived experience of religion that other biblical books have the task of defining. We can accept the Song of Songs as a love poem, Jeremiah’s Lamentations as a sequence of elegies, Job as a verse drama, and we discover without too much surprise a considerable number of poems in the historical books: the song of Moses and Miriam, for example, in Exodus 15; the canticle of Deborah and Barak in Judges 5; the lament of David for Saul and Jonathan in 2 Samuel 1. And yet when we think about the presence of all these poetic books in a work in which we expect to find doctrines, and about the turn to poetry in so many of the historical books of the Bible, it gives us reason to think again. And how should we react to Proverbs, in which wisdom itself is taught in a poetic form? Or to the prophetic books, where poetry is sovereign, where warnings of the greatest urgency, for us as well as for the writers’ contemporaries, come forth in verse?

Isn’t this curious? And poetry appears from the beginning. In the second chapter of Genesis (verse 23), Adam welcomes the creation of woman in this way:

Here at last the bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh.

This one shall be called woman, for she was drawn forth from man.

These are the very first human words reported; it is tempting and perhaps legitimate to draw some conclusions. By this point Adam has already named the animals, but the author only indicates this, without recording the spoken words; in the world of the beginning, from which the author knows himself as well as his readers to be excluded, he probably recognized that there must have existed an intimate relationship between language and the real, between words and things, that we are incapable of regaining. But when Adam does speak for the first time, he is given an “Edenic” language, one which our fallen languages can still attain in certain moments: thus Adam literally draws woman, ’ishah, from man, ’ish. Hebrew, thanks to the pleasure it takes in wordplay—in the ludic and deeply serious harmonies between the sounds of words and the beings, objects, ideas, and emotions to which they open themselves—is a language particularly and providentially skillful at suggesting what would be a cordial relation between our language and our world, and a meaningful relation among the presences of the real. It is skillful in affirming the gravity of the lightest among the figures of rhetoric: the pun. Most importantly, as soon as the first man opens his mouth, he speaks in verse. Did the author think that in the world of primitive wonder language was naturally poetic? Is this why Adam, immediately after eating the forbidden fruit, responds to God in prose: “I heard your steps in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked, and I hid myself” (Genesis 3:10)? We cannot know, but that first brief, spontaneous poem of Adam, which we seem to hear from so far away and from so close, solicits our attention and calls for our thought. If language before the Fall was poetic, or produced poems at moments charged with meaning, does poetry represent for us the apogee of our fallen speaking—its beginning and its end, its nostalgia and its hope?

In paging through Genesis, a book of history and not a collection of poetry, we encounter an impressive number of poems. It is in poetry that God gives the law on murder and its punishment (Genesis 9:6), that Rebecca’s family blesses her (24:60), that Isaac prophesies the future of Esau (27:39–40), and that Jacob blesses the twelve tribes of Israel (49:2–27). Given the occasional difficulty of identifying which passages are in verse, it may be that others will be discovered. The Bible de Jérusalem (I am reading from a 2009 edition) presents God as speaking in poetry several times in the first three chapters, beginning with the creation of man, as the Word of God gives birth to the only creature endowed with speech:

God created man in his image,

in the image of God he created him,

man and woman he created them.

In approaching the Bible’s beginning, we must often change our listening, our rhythm, our mode of attention and of being, in order to understand and receive a different language.

There are fewer poems in the New Testament, but they give even more food for thought. The Gospel of Luke introduces, from its first chapters, three poems: the canticles of Mary, Zachariah, and Simeon. Thus the Savior’s life begins under the sign of poetry. The book of Revelation, at the end of the Bible, contains additional canticles, as well as lamentations on Babylon, in poetry that appeals to the visionary imagination. In the name of Christianity, it returns to the extravagant poetry of the prophets. The first letter of John develops its thought with such felicity of rhythmic phrasing and close-crafted form that the Jerusalem Bible translates it completely in verse. These same translators have Paul’s letter to the Romans begin and end in verse, thus using poetry to frame a doctrinal exposition animated by an inflamed but in principle “prosaic” process of reflection, analysis, and synthesis.

Jesus himself seems at certain moments to speak in verse, as in the Beatitudes (Matthew 5, Luke 6) and the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6, Luke 11). In the Jerusalem Bible, the Gospel of John, which begins with a long poem and in which John the Baptist on two occasions speaks in verse (1:30, 3:27–30), suggests that Jesus the teacher—or rather, the divine educator—addressed his listeners most often in poetry.

It is true that the border between verse and a cadenced prose is not easy to determine in either the Hebrew of the Old Testament or the Greek of the New: translators judge it differently. It may also be that the poems spoken by Jacob, Simeon, and many others come not from them but from the authors of the books in which they appear. The result is the same. We find ourselves constantly in the presence of writings that invite us into the joy of words, into a well-shaped language, in a form that demands from us the attention that we give to poetry and awakens us to expectation.

***

Certain scholars of the Bible have long known that the poetry is not there simply to add a dash of nobility, or sublimity, or emotive force to what the author could have said in prose. They learned from literary critics what the critics had learned from poets: poetry is in itself a way of thinking and of imagining the world; it discovers with precision what it had to say only by saying it; the meaning of a poem awaits us in its manner of being, and meaning in the customary sense of the word is not what is most important about it.

Should we not ask ourselves if the presence of so many poems changes not only the way in which the Bible speaks to us, but also the kind of message, announcement, or call that it conveys? How must faith perceive biblical speech? What does this continual turn to poetry imply about the very nature of Christianity?

We can start to respond to these questions by giving some thought to how we usually read poetry. We do not paraphrase poems, extracting a meaning and leaving aside the redundant form. It is the very being itself of the poem that matters, the sounds and the rhythms that animate it like a living thing, the relations that the words stitch among themselves through their memory and their history, and the connotations that they disseminate.

However, while we read a poem of Keats, or of Baudelaire or Ronsard, in this way, we easily forget our customary attention to the life of the poetic word when reading, for example, a Psalm, from which we want to draw a teaching, a lesson. We need to be reminded of two well-known pensées of Pascal: “Different arrangements of words make different meanings, and different arrangements of meanings produce different effects”; “The same meaning changes according to the words expressing it.” Indeed, the meaning changes, and not only in poetry: Pascal speaks here of prose. The second fragment continues: “Meanings are given dignity by words instead of conferring it upon them.” I know no better formula for suggesting the inseparability of words and meanings. And if it is important not to depart from a biblical text written in prose, all the more so should we remain as close as possible to a biblical poem, knowing that poetry, which does not permit paraphrase, also does not convey propositions—or it conveys them in a context that gives them their specificity. It seems to me that we do not have to draw doctrines from the Bible other than those that the biblical writers themselves found there, for we cannot touch bottom in these deep waters; the world that is revealed to us entirely exceeds us. We can understand only what God reveals to us. The intelligence that he has given us allows us to reflect on what we read, but any attempt to go further—above all, systematic theology, whether it results in the Summa Theologiae of Thomas Aquinas or the Institutes of the Christian Religion of Calvin—seems an error.

To believe in the Bible—or, rather, to believe the Bible, and to allow oneself to be convinced that it is the word of God, in whatever way one considers it—is to believe what it says, with a supernatural faith that resembles, at an infinite distance, the confidence with which we read a poem, accepting that its reality is found in it and not in our exegeses. This allows for adhering to the truth that is at once included in the words and liberated by them, whatever the difficulty posed by the Flood, for example, or the Tower of Babel. We do not necessarily know the exact nature of the truth that is revealed to us, but we know where to look for it, just as we do not necessarily understand a poem but we look for the answer to our questions in the poem itself, without adding or subtracting anything.

Poetry attracts our attention to language and to the mystery of words, to their capacity to create, almost by themselves, networks of meaning, unexpected emotions, rhythms and a music for the ear and for the mouth that spreads through the entire body and all one’s being. It acts similarly on the world, by finding, for the presences of the real, new names, and associations of words, of cadences, of sounds, that give to the most familiar beings and objects a certain strangeness that is both disturbing and joyous. It burns up appearances, it uncovers the invisible, it opens, like a little casement or a great window, onto the unknown, onto something else. The shade of trees that invites us in the midst of strong heat is transfigured when Racine’s Phèdre cries:

Dieux! que ne suis-je assise à l’ombre des forêts!

(Gods! why am I not seated in the shade of forests!)

Reason or good sense might object that one cannot be seated in the shade “of forests,” but only in the shade of a tree, or, if one pictures it in the mind, in the shade of a forest, in the singular. These plural forests constitute a world seen anew, recreated by the imagination, a world of great beauty that is almost cerebral, but that at the same time in no way loses contact with reality. We are attracted by the grave sonority of “ombre,” which contrasts with the i sounds that precede it: “que ne suis-je assis …” The coolness of this shade, under forests that have become protecting and enveloping, creates for Phèdre an eminently desirable place, apt to save her from her burning unavowable love for Hippolyte and from the terrible gaze of the gods. The beneficial shadow trembles with a devastating passion; the imagined place is filled with human guilt.

The “meaning” of the famous verse depends on the imagination that inhabits it, and on the emotion that animates it, which would not be fully present without its grammar and without the sounds that it makes. The forests, real, surreal, and resonating with the character’s desire, shame, and aspiration, represent, in a sudden vision, the true world: loved, lost, possible. And I do not exclude the likelihood that these “forêts” are imposed on Racine by the necessity of rhyming them with “apprêts” at the end of the preceding line, and by the impossibility of writing the four syllables “de la forêt.” The arrival of poetry for a prosaic reason is not at all shocking: essential words and ideas frequently arrive in an oblique manner.

As Henri Brémond writes, poetry produces in us “a feeling of presence.” The world is there, not under its usual guise but in a language that alone can give it immediacy. The poetic act draws close to the real and, in order to go to the depth of things, it recreates them for us by welcoming them in sounds, rhythms, and unlimited ramifications of meanings, and places these recreations in the domain of the possible. In its own way, and without at all being supernatural, poetry too is a revelation. The Bible as revelation and as poetic speech gives equally and above all onto something else. Clearly, it does not develop exclusively in poems, but its writings often turn into verse, as if it tended toward poetry by supposing poetry to be the speech most appropriate to the strangeness, to the transcendence of what it manifests. And let us think again of the words of Jesus. He speaks quite often in parables, in order to present complex truths in the form of stories and within the life of a few characters, and in order to provoke his listeners—and us, his readers—to search, each time, for meaning in the multiple facets of a fiction. His affirmations in prose are equally poetic in that they are not understood right away; they ask that we receive them as we receive poetry, by becoming conscious of the mystery that accompanies them. For example, in hearing “The kingdom of heaven is very near,” or “This is my body,” or “I am the truth,” we feel, I believe, that they are something other than propositions, and we recognize behind these very simple words a sort of hinterland of meaning that we must explore as one explores the depths of a poem.

“I am the truth” escapes from all the modes of thinking in Western philosophy.

Jesus, who is the Word, speaks, indeed, and does not write. Everything he says follows from a particular situation, from a lived moment. And so many books of the Bible began by being spoken, or were destined, like the Psalms, to be said and sung, or they gather the words of an orator, like Ecclesiastes, or presuppose a dialogue, like Job or the Song of Songs. The Bible engages us constantly in listening, in becoming sensitive to their ways of writing, to images that do not explain, and, ideally, to the music of thought. It is true that most of us do not have access to the original texts, but wasn’t that foreseen? There are ways to understand, even at a distance, how Hebrew and Greek function, and it is up to us to seek, in a simple translation—on the condition that it is poetically faithful—the animation of the speech and the way and the life of the truth.

Reading the Bible is a “poetic” experience. It offers us a theology according only to the etymological sense of the word: speech concerning God. For the Bible, which puts us in front of something else, is itself other. Have we, in Europe, truly grasped the nature of Christianity? Haven’t we instead assimilated to our categories of thought and our habits of reading a religion that comes to us from the Middle East? Its Jewish origins in no way signify that Christianity lacks a universal bearing, but they must not be neglected. God chose to reveal himself first through a people that had, century after century, their own way of thinking and writing, and the religion they transmitted bears the marks of this genesis. The Bible asks us to recognize the strangeness, the foreignness of Christianity, and to put in question our European manner of approaching it. Recovering this Christianity that comes from elsewhere would change our reading of the Bible, and doubtless our way of proclaiming the Gospel.

Adapted from The Bible and Poetry by Michael Edwards, translated by Stephen E. Lewis. To be published by New York Review Books in August.

Michael Edwards is an Anglo-French poet and scholar. Born in Barnes, London, he is the author of twenty books and the first English person ever to have been elected to the Collège de France and to the Académie Francaise.

Stephen E. Lewis is a professor of English at the Franciscan University of Steubenville and a translator of French literature.

June 9, 2023

James Lasdun, Jessica Laser, and Leopoldine Core Recommend

Joxemai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Julian Maclaren-Ross’s 1947 novel, Of Love and Hunger, is a defiantly unedifying English comedy about a vacuum-cleaner salesman trying to keep his chin up in the gloom of prewar Brighton. Its not-quite-forgotten (if never-exactly-acclaimed) author has been on my radar ever since I learned that he was the model for the bohemian novelist character X. Trapnel in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. That monumental roman-fleuve of English life happened to be a significant inspiration for a project of my own—a novel about the seventies London I grew up in, an excerpt of which appears in the new Summer issue of the Review—so when I found myself trying to think of a book that one of my middle-aged characters might have read in her youth, the Maclaren-Ross novel sprang to mind, and I finally read it. As it turned out, I don’t think my character, a tortured soul who tends to find everything “ghastly,” would have enjoyed it. She would have found the seedy boarding houses and tearooms and pubs that comprise its setting “ghastly”; she‘d have found the petty swindling and debt-dodging antics of the protagonist and his fellow salesmen “ghastly,” and she’d have found his unapologetic romance with the wife of an absent colleague “too ghastly for words.” But I couldn’t get enough of it. There’s nothing obviously brilliant about the writing or plotting, both of which tend toward the studiedly humdrum. (“Two more cars passed, then a bus.”) But somehow its little throwaway visions of fleeting bliss snatched from abiding squalor got under my skin. I haven’t enjoyed a novel so much in ages.

—James Lasdun, author of “Helen”

I asked my musician friend JJ Weihl why so many analog demos sound like they were recorded at the bottom of the sea. She told me that if they’re recorded on a cassette there’s “far less frequency range—everything sounds warm and muffly.” She described something she experiences sometimes called demo-itis, when she gets so attached to the demo that it’s hard to recreate it later: “chasing the blurry undefined feeling,” she said.

Recently, I’ve been listening to old demo tapes by the Cure on repeat. I like hearing the rough and sometimes fragile beginnings of their songs. A demo feels more like it’s breathing—it’s not fixed. It has been through fewer hands and there’s something enthralling about that. The song is still thinking. The demo for “Six Different Ways” sounds underwater but the essence is there—maybe even more than in the finished song. There is a thinness, a wobbliness, and a directness to the recording—a distinctly temporary quality—not perfection—not in tune always. More the act of making a root.

My dog likes this instrumental demo of “Pictures of You”; he falls into a deep relaxed sleep whenever I play it. Robert Smith’s voice is there even when it’s not. Every performance of that song seems to have its own persuasive life force. Maybe more than one can be the one.

—Leopoldine Core, author of “ Ex-Stewardess ”

“My buckle makes impressions / on the inside of her thigh,” begins a Tyler Childers love song in which no one’s pants come off. “If I’d known she was religious / then I wouldn’t have came stoned,” he continues, and who wouldn’t forgive his honest mistake? He’s clearly hell-bound (“working on a building out of hand-hewn brimstone,” he sings in “I Swear (to God)”), until another song has him wondering whether God might let “free will / boys mope around in purgatory,” a place he describes as “a middle ground I think might work for me.” “Born Again,” which he has called “a redneck commentary on reincarnation,” repeats the phrase “once I was” (“a dying breed,” “a broken heart”), until it becomes simply: “once I was / and you were too.” It’s as though the clause thought it needed an object to become a full sentence, before realizing, in its journey toward enlightenment, that it was already complete.

In high school on the South Side of Chicago, I would say things like “I’ll listen to any music, just not country,” as if country were the only sure marker of bad taste, probably because of an unnamed association I had made, or that had been made for me, between the genre and white ignorance, unexamined patriotism (it is called “country,” after all), guns, Christianity, and the confederacy. In adulthood, I covered my burgeoning love for country music with the safer, cooler, more presentable term Americana. Until I fell for Childers, I didn’t see that term as a euphemism.

“As a man who identifies as a country music singer,” Childers said in his acceptance speech for the 2018 Americana Music Honors and Awards’s Emerging Artist of the Year, “I feel Americana ain’t no part of nothing and is a distraction from the issues that we’re facing on a bigger level as country music singers.” In 2020, he released Long Violent History, an album of old-time fiddle music accompanied by a six-minute YouTube statement in which he speaks directly to his “rural white listeners.” He asks them to “stop being so taken aback by Black Lives Matter: if we didn’t need to be reminded, there would be justice for Breonna Taylor,” and to “start looking for ways to preserve our heritage outside of lazily defending a flag with history steeped in racism and treason.” His most recent record, Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven?, does some of that heritage-preserving. It is a triune gospel album that plays the same eight songs three different ways—an acknowledgment of tradition, and that things change.

—Jessica Laser, author of “ Kings ”

June 8, 2023

Molly

If you are contemplating self-destruction, please tell someone you trust. Immediate counseling is available 24/7 by dialing 1-800-SUICIDE or 988.

A Sunday afternoon in early spring. We’d spent the morning quiet, in separate rooms—me in my office, writing; Molly on the bed in the guest room, working too, so I believed. I’d pass by and see her using her laptop or reading from the books piled on the bed where she lay prone, or sometimes staring off out through the window to the yard. It was warm for March already, full of the kind of color through which you can begin to see the blooming world emerge. Molly didn’t want to talk really, clearly feeling extremely down again, and still I tried to hug her, leaning over the bed to wrap my arms around her shoulders as best I could. She brushed me off a bit, letting me hold her but not really responding. I let her be—it’d been a long winter, coming off what felt like the hardest year in both our lives, to the point we’d both begun to wonder if, not when, the struggle would ever slow. I wished there could be something I might say to lift her spirits for a minute, but I also knew how much she loathed most any stroke of optimism or blind hope, each more offensive than the woe alone. Later, though, while passing in the hallway in the dark, she slipped her arms around me at the waist and drew me close. She told me that she loved me, almost a whisper, tender, small in my arms. I told her I loved her too, and we held each other standing still, a clutch of limbs. I put my head in her hair and looked beyond on through the bathroom where half-muted light pressed at the window as through a tarp. When we let go, she slipped out neatly, no further words, and back to bed. The house was still, very little sound besides our motion. After another while spent working, I came back and asked if she’d come out with me to the yard to see the chickens, one of our favorite ways to pass the time. Outside, it was sodden, lots of rain lately, and the birds were restless, eager to rush out of their run and hunt for bugs. Molly said no, she didn’t want to go, asked if I’d bring one to the bedroom window so she could see—something I often did so many days, an easy way to make her smile. I scooped up Woosh, our Polish hen, my favorite, and brought her over to the glass where Molly sat. This time, though, when I approached the window, Molly didn’t move toward us, open the window, as she would usually. Even as I smiled and waved, holding Woosh up close against the glass, speaking for her in the hen-voice that I’d made up, Molly’s mouth held clamped, her eyes like dents obscured against the glare across the dimness of the room. Woosh began to wriggle, wanting down. The other birds were ranging freely, unattended—which always made me nervous now, as in recent months a hawk had taken favor to our area, often reappearing in lurking circles overhead, waiting for the right time to swoop down and make a meal out of our pets. So I didn’t linger for too long at the window, antsy anyway to get on and go for my daily run around the neighborhood, one of the few reasons I still had for getting out of the house. I gripped Woosh by her leg and made it wave, a little goodbye, then hurried on, leaving Molly staring blankly at the space where I’d just been: a view of a fence obscured only by the lone sapling she’d planted last spring in yearning for the day she wouldn’t have to see the neighbors.

***

I corralled the chickens to their coop, came back inside. In Molly’s office, where I had a closet, I sat across from her while changing clothes in preparation for my daily run. Molly spoke calmly, said she’d just finished reading the galley of my next novel and that she liked the way it ended: with the book’s protagonist suspended in a stasis of her memories, forever stuck. I felt surprised to hear she’d finished, given her low spirit and how she’d said she found the novel difficult to read, because it hurt for her to have to see the pain behind my language, how much I’d been carrying around all this time. I told her I was grateful she’d made it through, that I wanted to hear more of what she thought after my run, already anxious to get on with it, in go-mode. My reaction seemed to vex her, causing a little back and forth where we both kept misunderstanding what the other had just said, each at different ends of a conversation. She remained flat on the bed as I kissed her forehead, squeezed her hand, then proceeded through the house, out the front door. Coming down the driveway, I took my phone out to put on music I could run to and saw I’d received an email, sent from Molly, according to the timestamp, just after I had left her in the room. (no subject), read the subject, and in the body, just: I love you, nothing else, besides a Word document she’d attached, titled Folk Physics, which I knew to be the title of the manuscript of poems she’d been working on the last few months. I stopped short in my tracks, surprised to see she’d sent it to me just like that, then and there. Something felt off, too out of nowhere—not like Molly, or perhaps too much like Molly. I turned around at once and went inside.

***

During my brief absence, she’d already risen from the bed, up and about for one of only a few times that day. I found her in the kitchen with the lights off, standing as if dazed by my appearance, arms at her sides. She seemed to clench up as I came near, letting me put my arms around her but staying taut, hand on my chest. She hesitated when I asked if she’d finished her manuscript, wondering why she hadn’t mentioned it. Yes, she said quietly, she guessed it was finished, a draft at least but no big deal. I told her I was excited to get to read it either way, that I was proud of her, and squeezed her tightly one more time, then let her go. She seemed to hover there in front of me a moment, waiting mute for what I’d do next. I asked if after my run we could go to Whole Foods, pick up something to make for dinner together, and maybe watch a movie, have a nice night here at home. She said yes, that sounded good, and I said good, I’d see her soon, then one last hug before I left her standing in the kitchen in the dark.

***

On my run, I followed my usual route around our neighborhood without much thought. I’d always liked the way the world went narrow in this manner during exercise, as if there could be nothing else to do but the task at hand, one foot in front of the other, counting down without a number. I don’t remember seeing any other people, then or later, though I must have; in retrospect, the smaller details would fade to gray around the corridor of time sent rushing forward in the wake of what awaited just ahead. Near the end of the run, I decided to extend my route, turning around to double back the way I’d just come, adding on an extra half-mile on a path that took me past the entrance to the gardens where Molly and I would often walk in summers. The sidewalks in this part of the neighborhood were cracked and bumpy, requiring specific care not to trip. I pulled my phone out to see how far I’d gone and saw a ping from Twitter telling me that Molly had made a post, just minutes past—a link to a YouTube video of “The Old Revolution” by Leonard Cohen, including her transcription of the song’s opening line: “I finally broke into the prison.” I liked the tweet and thumbed the link immediately, opening the song to let it play, happy to imagine her selecting the closing soundtrack for my run home, just a couple blocks away now. “Into this furnace I ask you now to venture,” Cohen sang, backed by a doomy twang. “You whom I cannot betray.”

***

The song was still there with me in my head as I arrived back at our driveway, where looking up from halfway along the path toward the stairs to our front porch, I saw a shape against the door, covering the spy hole—a plain white envelope, affixed with tape. My body seized. From early on in our relationship I’d had visions of Molly picking up and leaving just like that, deciding on a whim and without warning that she preferred to be alone. Running up the steps, already flush with adrenaline, a pounding pulse, I saw my first name, Blake, handwritten in the center of the envelope’s face in Molly’s script. Immediately, I wailed, devoid of language, too much too fast, real and unreal. Inside the envelope, a two-page letter, printed out. I stopped cold on the first lines:

Blake,

I have decided to leave this world.

Then there was nothing but those words—words to which I have no corollary, no distinct definition in that moment, as simple as they seem. Every sentence that I’ve tried to put here to frame the moment feels like a doormat laid on blood, an unstoppable force colliding with an intolerable object in slow motion, beyond the need of being named. Before and after.

***

Out of something akin to instinct, I forced my sight along the rest of the letter, not really reading it so much as scanning for a more direct form of information, anything she’d written that might tell me where she was—which, near the end of the second page, I found: I left my body in the nature area where we used to go walking so I could see the sky and trees and hear the birds one last time. Then: I shot myself so it would be over instantly with certainty and no suffering whatsoever. This time when I screamed it was the only word that I could think of: No. I must have sounded like a child jabbed in his guts, squealing. I knew exactly where she meant—I’d run right by it, just minutes before, perhaps a couple hundred yards away. I might have even crossed her path while on the way there had times aligned right, had I known. A sudden frenzy of possible options of what to do next swarmed my brain, none of them quite right, devised in terror.

***

At the edge of the sidewalk, I stopped and tried to think if I should go inside and get my keys and drive to where she might be, or if I should run there fast as I could, still in my running clothes, already half-exhausted and slick with sweat. Each instant that I didn’t do exactly the right thing felt like the last chance, a window closing. Finally, I took off running at full speed along the sidewalk, shouting her name loud as I could, begging her or me or God or whoever else might be able to hear me: No, please, Molly. Not like this. No matter what I said, there was no answer; no one on the street around me, zero cars. Ahead, the sidewalk seemed to stretch so far beyond me, no matter how fast or hard I ran, as if growing longer with every step; all the houses shaped the same as they were always, full of other people in the midst of their own lives. As I ran, I tried to scan her letter, held out before me with both hands, already wadded up in frantic grip, scanning through fragments of despondent logic that felt impossible to connect with any actual moment in the present as it passed. “Everyone’s life ends, and mine is over now,” she’d written in present tense about the future, which was apparently in the midst of happening right now—or had it already happened? Was there still time? I felt embarrassed, sick to my stomach, to feel my body’s power giving out no matter how hard I tried to maintain the sprint, forced instead at several points to slow down against the burning in my muscles, sucking for air with everything I thought I knew now on the line.

***