The Paris Review's Blog, page 52

June 29, 2023

Diary, 2021

In these pages, written in 2021, I seem to have been looking back at earlier notes and journals. The story of Pierre—a French shepherd—is a project imagined decades ago that I still have not given up on. My “theories” are also still interesting to me: for instance, that maybe certain people are more inclined to violence when there is less sensuality of other kinds in their lives.

Lydia Davis’s story collection Our Strangers will be published in fall 2023 by Bookshop Editions. Selections from her 1996 journals appear in the Review‘s new Summer issue, no. 244.

June 28, 2023

A Summer Dispatch from the Review’s Poetry Editor

Detail from the cover art of issue no. 244: Emilie Louise Gossiaux, London with Ribbon, 2022, ballpoint pen on paper.

There’s a thrill of eros to many summer poems. Like in those late-eighties teen movies—Dirty Dancing, Say Anything, One Crazy Summer—you never know when you’ll see some skin. And so it goes in our new Summer issue. In Jessica Laser’s dreamy, autobiographical remembrance “Kings,” the poet recalls a drinking game she used to play in high school on the shore of Lake Michigan over summer vacations:

… You never knew

whether it would be strip or not, so you always

considered wearing layers. It was summer.

Sometimes you’d get pretty naked

but it wasn’t pushy. You could take off

one sock at a time.

Is that easygoing, one-sock-at-a-time feeling what defines the summer fling? Maybe that’s just how objects appear in the rearview mirror; even the most operatic affairs can seem a little comical in retrospect. In his poem “Armed Cavalier,” Richie Hofmann captures the hothouse kind of summer romance, when two lovers lock themselves away “for a whole weekend / and not eat or drink.” I love the wry look he casts over his shoulder at the end of these lines:

Stars, slow traffic,

the summer I wished you loved me

enough to kill me,

but not really.

If you’re curious to learn more about the story behind “Armed Cavalier,” check out our online Making of a Poem series feature on his poem this month. Leopoldine Core, whose poem “Ex-Stewardess” appears in this issue, recently contributed to the series, too—and to my summer playlist. “I was listening to Tangerine Dream, Ryuichi Sakamoto, ‘Dance II’ by Discovery Zone, and this mournful song ‘Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms,’ performed by Mia Farrow in The Muppets Valentine Show in 1974,” Core recalls. I’m listening to Farrow’s Muppets Show rendition as I write this, and Core’s right, she does sound “a little like Nico.”

They say that on hot summer days in the nation’s capital, Richard Nixon would light a roaring blaze in the fireplace of his White House study, crank the air conditioning up to full blast, put on a little Mantovani, and gaze out the window at the Washington Monument. This might be one of the few things Nixon and I have in common; while my fellow Americans are out in droves worshipping the sun, I like nothing more than to retreat to my home office and, thermostat set to eco mode, leaf through poems about summer. In this issue’s pages, fellow seasonal voyeurs will find that Lewis Meyers’s “Summer Letters” delivers “the black raspberry’s passion for a drop of sunlight” without any need for sunscreen. “Summer Letters” marks the late Meyers’s return to our pages after more than a half century; his last poem in the magazine, “Going to Chicago,” was published in a 1965 issue, under the Johnson administration. We’re grateful to Meyers’s widow, Diana, and to the poet Ellen Doré Watson, for sharing the poem with us.

Elsewhere, Sharon Olds muses on her quest to find a better language for sex in her Art of Poetry interview, and John Keene, in his Art of Fiction interview, observes that Portuguese is better suited to that task than English. It should also be said that, although we tried our best, not every poem in this issue is about summer, sex, or summer sex. You’ll also find a philosophical poem about cats by the great Argentinian writer Mirta Rosenberg, translated from the Spanish by Yaki Setton and Sergio Waisman; an excerpt from Imani Elizabeth Jackson’s expansive minimalist sequence “Flag”; and a poetic noir set in the Antwerp of Jonathan Thirkield’s singular imagination. Bon voyage, and happy reading.

Srikanth Reddy is the Review‘s poetry editor.

June 27, 2023

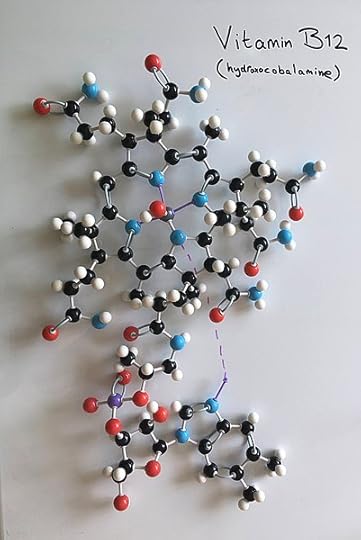

On Vitamins

Molecular model of Vitamin B12. Licensed under CCO 4.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Three years ago, I biked into a curb and fell on my head. When I got up, I couldn’t remember where I was, so I called an ambulance, which drove me to the nearest hospital, which was apparently one block away. The emergency room doctors told me there was nothing they could do. My eye was swollen, but my face seemed otherwise normal, and they wouldn’t know if anything was wrong with my brain unless they ran a CAT scan, which would expose me to toxic radiation. I asked if there were any nontoxic tests they could run for free. They offered to run a blood panel, which would let me know if I had any STIs. I let them bind my forearm, which had nothing to do with my head.

The next day, the doctor sent a message through the hospital’s online portal. My tests were all came back negative, but they had also run a nutrient panel, and I was deficient in B12. I started googling. “Fell off bike low B12?” Everything that came up was random; I might as well have strung together any other combination of five words. I wanted to google more, but the doctor had told me that the internet was bad for my concussion. So I forgot about my deficiency and tried hard to make my body do nothing, which was the only way for it to heal.

Things got better. I started to feel normal, and eventually I was allowed to google as much as I wanted. Years went by. And then one day at a café, I met a man—a comedian—who told me horror stories about his life as a former vegan. His hair had fallen out, he was exhausted, his mood was always sour, and it was all because of vitamins: he could never get enough of them. While he complained, I felt my hairline receding; I was a vegan, too. And when I thought about it, really thought about it, my personality was on the decline. I was always struggling to make my days have meaning, and I wore my meaninglessness like a divine premonition. (“I have a feeling,” I texted a friend, “that something bad, really bad, is going to happen.”) I remembered the emergency room doctor’s diagnosis and felt the empty place inside of me where all the B12 supplements should have been, leeching into my bloodstream.

I tried to make a doctor’s appointment, but I had moved to California, and my insurance only covered care in New York. My body was on the West Coast, but all the tools I had for reading it were on the East. I told my father I was coming home to visit him, and when I arrived, asked him to drop me off at urgent care.

“Sorry,” said the receptionist. “The only blood work we do is for STIs. Nutrition panels aren’t urgent.”

I called my primary care physician’s office and told them that I had a need, a pressing need, for a B12 test. Everything I was feeling—daily bouts of idiocy, a persistent feeling of doom—was perfectly summarized by the deficiency symptoms I found online: headaches, psychological problems, palpitations, dementia. The receptionist told me that a nurse practitioner would be able to draw blood the next day—not soon enough. I requested a personal day from work and went to CVS, where I bought a bottle of supplements labeled “maximum strength.” Each pill contained 5,000 mcg of B12, which is 208,000 percent times the recommended daily value. They weren’t even vegan, but I took a double dose, hoping it would tide me over until my appointment, after which I was sure the doctor would put me on an emergency course of injections.

My brain was becoming an abacus. It was almost impossible to feel my feelings without translating them into the language of diagnosis, which was laughably general and yet strangely precise: symptoms claimed to contain the spectrum of human experience, but reduced that experience to a dozen ugly words. The vitamins themselves could counteract those ugly words because they contained good words of their own. Happiness, energy, valiance, relaxation: swallowing them daily felt like ingesting a little promise, saying a little prayer. How else could I communicate with my body besides putting speech inside it?

Anyway, my appointment came and went. No one called to give me my results, and when I checked the online portal, I noticed that my doctor, who hadn’t even seen me directly, who was in the habit of using the euphemisms “number one” and “number two,” had left me a message. “Hi mya—everything is looking great : ) No need for a follow-up at this time.” I checked the numbers. My B12 levels had surpassed the minimum threshold; they had even surpassed the desirable range. The pills had worked, and they had worked too well. The data, my data, had been contaminated: the language on the screen had nothing to do with what was happening in my body. And yet the doctor depended upon that language to approach my body, even though my body had been in front of her, trying to announce its problems.

I wanted the numbers to go down. Once they went down, I could prove to my doctor that they needed desperately to go back up. And so, I stopped taking the supplements, and the B12 slowly left me, detaching itself from my vocabulary until it became an abstract problem, a nonurgent problem, a random string of letters and numbers whose meaning was obscure to me, and which was no longer a metaphor for happiness.

Maya Binyam is a contributing editor of the Review. Her novel, Hangman, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in August.

June 26, 2023

Making of a Poem: Leopoldine Core on “Ex-Stewardess”

Leopoldine Core’s aura photo, courtesy of the author.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Leopoldine Core’s “Ex-Stewardess” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 244.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

Often a poem begins wordlessly. It’s as if the text is a reply to some cryptic spot in the back of my brain that I have become attracted to. I’m alerted to the presence of something that isn’t solid. It has more to do with feeling, tempo, scale, and temperature. I’m so focused on that emanating region that, even though I’m using words, my experience—the start of it—is wordless and meditative.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? (Are there hard and easy poems?)

Some poems come quick and others take a while. But maybe the one that took years was easier in the end—I don’t know. Certain poems require many rounds of rewording. When this happens I will rewrite one line forty or more times, then narrow it down to thirty, then fifteen, then five, then choose.

But this poem was realized fairly quickly and required zero rewording. That happens sometimes. I tried rewording certain parts at different points but always wound up reverting to the original. The editing I did consisted of deleting maybe seventy percent of what was there, changing the order, capitalizing certain letters, and adding line breaks. I might have added a comma but I don’t think so.

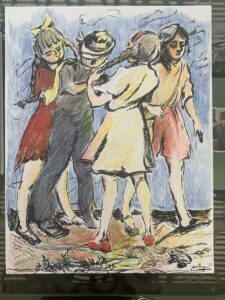

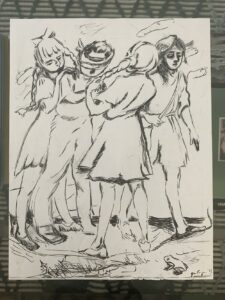

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

Occasionally my friend Jane Corrigan will send me pictures of her paintings and drawings. There are two she showed me around that time—one is a pen drawing and the other is a Xerox of that same drawing that she drew over with pen and colored in with pencil. Jane’s images are infused with such narrative possibility—I like to stare at them for a long time, putting order to the plot. This one seems like a scene from some lost Jane Bowles story.

I wasn’t thinking consciously of these drawings while writing the poem, but there’s something so joyful and stimulating about discourse with friends. I like talking about art that isn’t mine.

Courtesy the author and Jane Corrigan.

Courtesy the author and Jane Corrigan.

What else were you listening to / reading / watching while you were writing this poem?

I was reading a collection of interviews with the filmmaker Claude Chabrol. I underlined this sentence—“I like mirrors, because they are a way of crossing through appearances.” He was talking about manipulating space but I was drawn to a conceptual meaning of the statement—how something solid that reflects the surface of things can also function as an entryway, a portal.

I was listening to Tangerine Dream, Ryuichi Sakamoto, “Dance II” by Discovery Zone, and this mournful song “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” performed by Mia Farrow in The Muppets Valentine Show in 1974. I love how sincerely she sings to that puppet. She sounds a little like Nico. And there’s something about the confluence of optimism and despair in her voice that might have influenced me.

It also seems relevant to mention that I had gotten an aura photo taken around that time—I kept looking at it. The aura photo I had taken a few years before was mostly red with a cloud of yellow and orange. I was told at the time that the color red implies a closeness to Earth.

But this one was so blue. I kept wondering what that meant. Where was my spirit in relation to Earth? Was it farther from Earth now? I was—am still—grieving the loss of someone I love dearly, and looking at the photo made me think of a sky within.

What was the challenge of this particular poem?

Writing in code. And leaving room for interpretation. The metaphors are there—the stewardess, travel, the dog, the sky, et cetera—but they can also be taken literally. They are what they are and they are something else too.

The poem could be about someone who really reincarnated all these different times and remembers those past lives—though I was thinking more about how we reincarnate many times within a single lifetime, both in terms of how we are seen and in terms of how we really are. We are reborn in the sense that we transform. And yet we carry impressions of the interminable past within us.

I was also thinking about the experience of being objectified over and over. And how those experiences can shape one’s worldview, their sense of what is possible and impossible—and also their sense of time. Stewardess is a dated term that seems, in the poem, to be asking, But has anything changed? Can one really be an ex-stewardess if the treatment is the same? Then it becomes a question of hope—what it might be made of. The poem ends with the act of drawing “an imaginary / animal,” by which I mean the self, and “a field and the / sky”—by which I mean the world. It felt important to depict selfhood in the throes of the imagination—one who works to escape an external gaze, knowing they are not limited to how they are seen, knowing they are multiple.

Leopoldine Core is the author of the poetry collection Veronica Bench and the story collection When Watched, which won a Whiting Award and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. She is a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in The Paris Review, PEN America, Apology Magazine, The American Poetry Review, BOMB, and The Best American Short Stories, among others. She has taught at NYU and Columbia University.

June 23, 2023

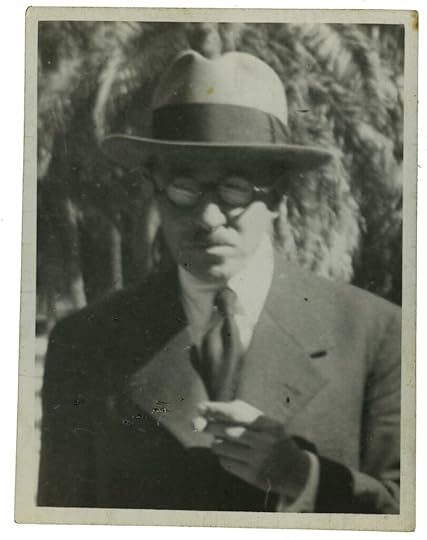

Fernando Pessoa’s Unselving

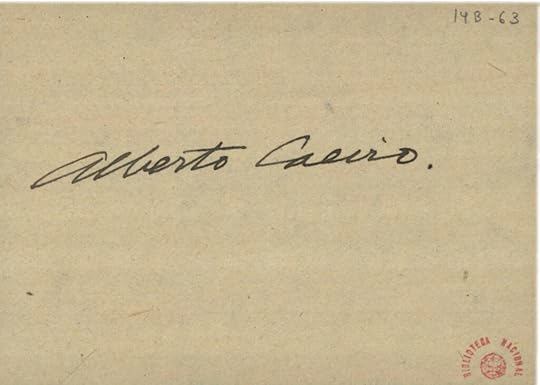

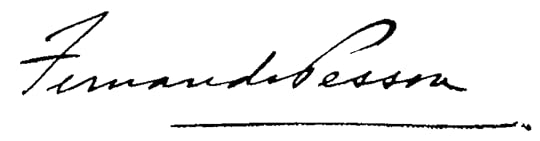

Pessoa in 1934. From Os Objectos de Fernando Pessoa | Fernando Pessoa’s Objects by Jerónimo Pizarro, Patricio Ferrari, and Antonio Cardiello. Courtesy of the Casa Fernando Pessoa and Dom Quixote.

On July 11, 1903, a long narrative poem called “The Miner’s Song” by Karl P. Effield appeared in the Natal Mercury, a weekly newspaper in Durban, South Africa. Effield—who claimed to be from Boston—was actually none other than the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, then a high school student in Durban. This was the first of Pessoa’s English-language fictitious authors to appear in print—the beginning of Pessoa’s unusual mode of self-othering. The adoption of different personae allowed him to go beyond a nom de plume, and take on unpopular, controversial, and even extreme points of view in both his poetry and prose.

While in South Africa, where Pessoa lived between 1896 and 1905, he sent another work to the Natal Mercury under the name of Charles Robert Anon, attempting without success to publish three political sonnets about the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Pessoa’s early fictitious authors wrote in English, French, and Portuguese—the three languages he continued to use until he died, at age forty-seven. These first invented writers, which he would go on to call “heteronyms,” composed loose texts mostly in the form of first drafts; but others, like Bernardo Soares (whom Pessoa created around 1920) or the major heteronyms (Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis in 1914), produced a very solid body of work. By the time Pessoa was twenty-six years old, he had already invented a hundred literary personae.

Alberto Caeiro was the central fictitious figure of Pessoa’s literary universe. Born in Lisbon on April 16, 1889, Caeiro died of tuberculosis in 1915. Pessoa said that Caeiro poetically arrived in his life on March 8, 1914—which in a famous letter to the Portuguese literary critic Adolfo Casais Monteiro he described as a “triumphal day.” The poet and novelist Mário de Sá-Carneiro was one of Pessoa’s closest friends in Lisbon, and Caeiro (perhaps a pun on Sá-Carneiro’s name) seems to have come into being as a joke: “I thought I would play a trick on Sá-Carneiro and invent a bucolic poet of a rather complicated kind,” wrote Pessoa in the same letter. Caeiro’s “death” seems to have been influenced, in retrospect, by Sá-Carneiro’s suicide in Paris on April 26, 1916. As Pessoa wrote in the review Athena in 1924, “Those whom the gods love die young.” By that time, he had produced the body of poems for which Caeiro would be remembered—The Keeper of Sheep.

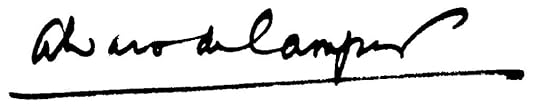

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

Then there was Álvaro de Campos, the most prolific and eccentric of Pessoa’s heteronyms. In the aforementioned letter to the critic, we find the most complete description of him: “Campos was born in Tavira, on October 15, 1890…. He is a naval engineer (by way of Glasgow)…, tall (5 feet, 74 inches—almost one more inch taller than me), thin and a bit prone to crouching…. [He is] between white and dark, vaguely like a Portuguese Jew; [his] hair, however, is smooth and normally pushed to the side, [he wears a] monocle…. He received an average high school education; then he was sent to Scotland to study engineering, first mechanics and then naval.” Álvaro de Campos was a self-indulgent and bisexual dandy who celebrated the modern world with its roaring of machines and the hustle and bustle of city life.

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

Pessoa links Campos to an array of literary influences, “in which Walt Whitman predominates, albeit below Caeiro’s,” and wrote that he had decided Campos to produce “several compositions, generally scandalous and irritating in nature, especially for Fernando Pessoa, who, in any case, produces and publishes them, however much he disagrees with such texts.” Undoubtedly Campos was Pessoa’s most sardonic and fierce of the heteronymic voice, sharing biographical facts with Nietzsche (also born on October 15) and affinities with Blake (“Like Blake, I want the close companionship of angels”)

The literary works of Campos may be split into three phases: the decadent (dandy) phase, the futuristic phase, and the pessimistic (existentialist) phase. Campos shows mixed affinities with Whitman and the Italian futurist F. T. Marinetti, mainly in the second phase: poems like “Triumphal Ode,” “Maritime Ode,” and “Ultimatum” praise the power of rising technology, the strength of machines, the dark side of industrial civilization, and an enigmatic love for machineries. In the last phase, Pessoa qua Campos reveals the emptiness and nostalgia that may come in the winter of one’s life. This was when he wrote poems such as “Lisbon Revisited” and “Tobacconist’s Shop,” the long, nihilistic poem of defeat written in 1928 and published five years later in the review presença. Considered one of the monuments of modernist poetry, it opens thus:

I’m nothing.

I’ll always be nothing.

I can’t even hope to be nothing.

That said, I have inside me all the dreams of the world.

Although Campos wrote poetry and prose in Portuguese, he also used English and French in some of his lines and titles. Among his most noteworthy prose writings we find “Notes in Memory of My Master Caeiro,” published in the Presença journal in 1931. In these notes, Campos offers an elucidating description of himself:

I am exasperatingly sensitive and exasperatingly intelligent. In this respect (apart from a smidgeon more sensibility and a smidgeon less intelligence) I resemble Fernando Pessoa; however, while in Fernando, sensibility and intelligence interpenetrate, merge and intersect, in me, they exist in parallel or, rather, they overlap. They are not spouses, they are estranged twins.

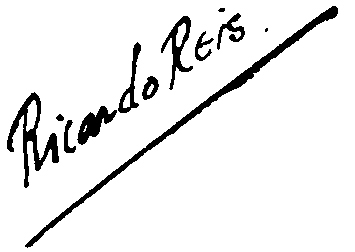

In the same letter to Casais Monteiro from 1935, Pessoa provides a detailed description of Ricardo Reis, his third major heteronym—defining him as a doctor from Porto, born in 1887, educated in a Jesuit college, and living in Brazil since 1919, out of fidelity to his monarchical ideals. Pessoa also adds to this portrait that Reis learned Latin through someone else’s education—probably with the Jesuits—and Greek by himself. These details serve to humanize the classicist Reis, the serious, measured, and semi-indolent Reis, who should embody a neoclassical theory opposed to “modern romanticism” and “neoclassicism in the manner of [Charles] Maurras.” Reis wrote epigrams and elegies, in addition to odes, and his poetry is largely characterized by the use of specific meters (especially the regular use of decasyllabic verses alternating, or not, with hexasyllables). Pessoa-cum-Reis wrote a substantial body of poetry and prose. Among the latter we find texts on paganism as well as the oft-cited essay “Milton Is Greater Than Shakespeare.” In his prose Reis makes a vehement claim to Hellenism and issues a firm condemnation of Christianity. He criticizes Matthew Arnold, Walter Pater, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Oscar Wilde, among others—a kind of predecessor to contemporary neo-pagan aesthetes and theorists who are not entirely freed from Christian sentimentality.

Courtesy of Tinta da china.

***

Fernando Pessoa’s modernist epic is the result of a radical displacement of the subject, which he described as a “drama in people”—made up of the poetic trio and his other aliases who Pessoa gradually crafted between languages, a vast collection of books, and Lisbon—the beloved city of his birth.

Following the publication of The Book of Disquiet in 2017, I met with the New Directions vice president and senior editor Declan Spring in New York City suggesting that we bring out Pessoa’s major heteronyms in the same order that Pessoa himself had birthed them. Thus, we started with Alberto Caeiro, master of the coterie. While The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro came out in the summer of 2020, The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos is forthcoming on July 4, 2023. These three Pessoa books—all including some facsimiles from the Pessoa papers held at the National Library of Portugal—will be followed by The Complete Works of Ricardo Reis.

In translating Pessoa’s heteronyms, one thing we see clearly is the influence of reading on Pessoa’s plural and inquiring mind. I have no doubt that reading more than writing was his primary and long-lasting literary occupation. His marginalia are of great interest; so are his many influences. This is to say that the more we know about what Pessoa read and when, the better equipped we are as translators of his works—especially to see more clearly his poetical diction, meters, and rhythms at the core of each heteronymic voice.

Courtesy of tinta da china.

On November 29, 1935, while lying in bed at the Hôpital Saint Louis des Français, Fernando Pessoa wrote his last words: “I know not what to-morrow will bring.” In the translation of an epigram by Palladas of Alexandria, published in the first volume of the Greek Anthology and still in his private library, we read the following pencil-marked closing line: “To-day let me live well; none knows what may be to-morrow.” Whether this depicts the consummation of a life consecrated to literature or the memory of Pessoa, it reconfirms the fact that Pessoa’s writings emerged from an intense contact with a vast array of books. His work has reconfigured literature, including the way we look at literature. May our century be one for such multitudinous Pessoa.

The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos by Fernando Pessoa, edited and introduced by Jerónimo Pizarro and Antonio Cardiello, and translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, will be published by New Directions in July. Ferrari has translated Fernando Pessoa, Alejandra Pizarnik, and António Osório, among others. He is a polyglot poet, translator, and editor, resides in New York City, and teaches at Sarah Lawrence College. Ferrari is currently working on “Elsehere,” a multilingual trilogy.

Poetry and prose quoted from The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos (2023) and Alberto Caiero: Complete Works (2020) by Fernando Pessoa. Used with permission of New Directions Publishing.

Beyond ChatGPT

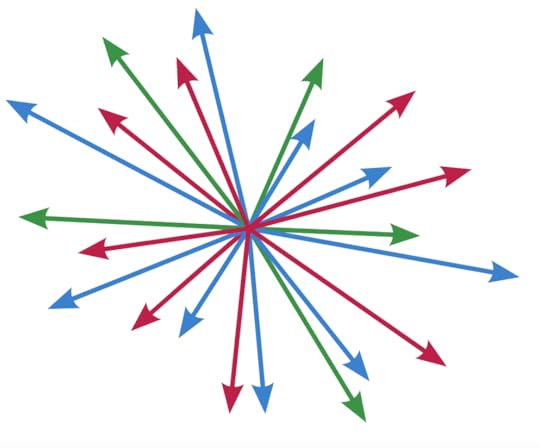

Oleg Alexandrov, vector space illustration. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Counterpath Press’s series of now thirteen computer-generated books, Using Electricity, offers a refreshing alternative to the fantasia of terror and wonder that we’ve all been subjected to since the public release of ChatGPT. The books in this series present us with wide-ranging explorations into the potential interplay between human language and code. Although code-based work can be dauntingly hermetic to the noncoder, all computationally generated or mediated writing is the result of two fundamental decisions that remain in the hands of the human author: defining the source text(s) (the data) and choosing the processes (the algorithms or procedures) that operate on them. A text generator like ChatGPT uses brute force on both sides—enormous amounts of text vacuumed from the internet are run through energy-intensive pattern-finding algorithms—to create coherent, normative sentences with an equivocal but authoritative tone. The works in Using Electricity harness data and code to push language into more playful and revealing imaginative territory.

Many of Using Electricity’s authors mobilize computational processes to supercharge formal constraints, producing texts that incessantly iterate through variations and permutations. In The Truelist, Nick Montfort, the series editor, runs a short Python script to generate pages of four-line stanzas comprising invented compound words. “Now they saw the lovelight, / the blurbird, / the bluewoman facing the horse, / the fireweed.” The poem is a relentless loop—repeating this same structure as it churns through as many word combinations as it can find. Rafael Pérez y Pérez’s Mexica uses a pared-down, culturally specific vocabulary and a complex algorithm to generate short fairy tale–like stories. One begins, “The princess woke up while the songs of the birds covered the sky.” The skeletal story structure swaps different characters and actions as the variations play out. It’s like watching a multiversal performance of the same puppet show.

I find that often I am not reading these works for meaning as much as for pattern, which is at the heart of how computation operates. Allison Parrish’s fantastic Articulations brings us frighteningly deep into the core of computational pattern searching. Drawing from a corpus of over two million lines of poetry from the Project Gutenberg database, she takes us on a random walk through “vector space.” Put simply, this is the mathematical space in which computers plot similarities between different aspects of language—the sound, the syntax, whatever the programmer chooses. The result is a dizzying megacollage/cluster-mash-up of English poetry in which obsessive and surprising strings constantly emerge—a vast linguistic hall of mirrors. “In little lights, nice little nut. In a little sight. In a little sight, in a little sight, a right little, tight little island. A light. A light. A light. A light. A light.”

Many of these works are indebted to the wider traditions of procedural, concrete, conceptual, and erasure poetry, while making use of code’s unique possibilities for play, chance, variation, and repetition. Stephanie Strickland’s Ringing the Changes draws its mathematical ordering process from a centuries-old practice of English bell ringing. In Experiment 116, Rena Mosteirin plays a game of translation telephone by running Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 116” through multiple languages in Google Translate and back into English.

The three most recent titles, released in April, comprise some of the series’s most varied and dynamic approaches to digital poetics. There is an updated edition of Image Generation by the pioneering literary artist John Cayley; as well as Qianxun Chen and Mariana Roa Oliva’s Seedlings, which uses the metaphor of seeds and trees, and “grows” word structures that evoke the dynamics and fragility of plant life. One of the most exciting titles thus far, especially from the perspective data source, is Arwa Michelle Mboya’s Wash Day, in which she threads together transcripts of YouTube videos of Black hair vloggers sharing their Wash Day rituals. The result is an immersive, polyvocal, multiauthored narrative that reveals the unique capacity of data and computation to give presence to specific communities. Wash Day provides an extraordinary contrast to the normalized, bulk-writing superstores of commercial text generators. That deep attention to language—its potential, its limits, its expressive capabilities, its necessity, and its fragility—is the central quality all these authors share. Hopefully works like theirs can help us imagine much more resonant and compelling digital futures.

Jonathan Thirkield is a poet, coder, and digital artist. He teaches computational media and digital arts at The New School, Parsons, and Columbia University. His second collection of poetry, Infinity Pool, is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press in fall 2024. His poem “Antwerp (2)” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 244.

June 21, 2023

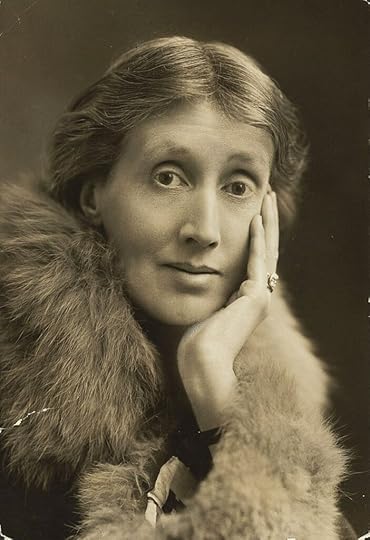

Virginia Woolf’s Forgotten Diary

Virginia Woolf, wearing a fur stole. Public domain, courtesy of wikimedia commons.

On August 3, 1917, Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary for the first time in two years—a small notebook, roughly the size of the palm of her hand. It was a Friday, the start of the bank holiday, and she had traveled from London to Asheham, her rented house in rural Sussex, with her husband, Leonard. For the first time in days, it had stopped raining, and so she “walked out from Lewes.” There were “men mending the wall & roof” of the house, and Will, the gardener, had “dug up the bed in front, leaving only one dahlia.” Finally, “bees in attic chimney.”

It is a stilted beginning, and yet with each entry, her diary gains in confidence. Soon, Woolf establishes a pattern. First, she notes the weather, and her walk—to the post, or to fetch the milk, or up onto the Downs. There, she takes down the number of mushrooms she finds—“almost a record find,” or “enough for a dish”—and of the insects she has seen: “3 perfect peacock butterflies, 1 silver washed frit; besides innumerable blues feeding on dung.” She notices butterflies in particular: painted ladies, clouded yellows, fritillaries, blues. She is blasé in her records of nature’s more gruesome sights—“the spine & red legs of a bird, just devoured by a hawk,” or a “chicken in a parcel, found dead in the nettles, head wrung off.” There is human violence, too. From the tops of the Downs, she listens to the guns as they sound from France, and watches German prisoners at work in the fields, who use “a great brown jug for their tea.” Home again, and she reports any visitors, or whether she has done gardening or reading or sewing. Lastly, she makes a note about rationing, taking stock of the larder: “eggs 2/9 doz. From Mrs Attfield,” or “sausages here come in.”

Though Woolf, then thirty-five, shared the lease of Asheham with her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell (who went there for weekend parties), for her, the house had always been a place for convalescence. Following her marriage to Leonard in 1912, she entered a long tunnel of illness—a series of breakdowns during which she refused to eat, talked wildly, and attempted suicide. She spent long periods at a nursing home in Twickenham before being brought to Asheham with a nurse to recover. At the house, Leonard presided over a strict routine, in which Virginia was permitted to write letters—“only to the end of the page, Mrs Woolf,” as she reported to her friend Margaret Llewelyn Davies—and to take short walks “in a kind of nightgown.” She had been too ill to pay much attention to the publication of her first novel, The Voyage Out, in 1915, or to take notice of the war. “Its very like living at the bottom of the sea being here,” she wrote to a friend in early 1914, as Bloomsbury scattered. “One sometimes hears rumours of what is going on overhead.”

In the writing about Woolf’s life, the wartime summers at Asheham tend to be disregarded. They are quickly overtaken by her time in London, the emergence of the Hogarth Press, and the radical new direction she took in her work, when her first novels—awkward set-pieces of Edwardian realism—would give way to the experimentalism of Jacob’s Room and Mrs. Dalloway. And yet during these summers, Woolf was at a threshold in her life and work. Her small diary is the most detailed account we have of her days during the summers of 1917 and 1918, when she was walking, reading, recovering, looking. It is a bridge between two periods in her work and also between illness and health, writing and not writing, looking and feeling. Unpacking each entry, we can see the richness of her daily life, the quiet repetition of her activities and pleasures. There is no shortage of drama: a puncture to her bicycle, a biting dog, the question of whether there will be enough sugar for jam. She rarely uses the unruly “I,” although occasionally we glimpse her, planting a bulb or leaving her mackintosh in a hedge. Mostly she records things she can see or hear or touch. Having been ill, she is nurturing a convalescent quality of attention, using her diary’s economical form, its domestic subject matter, to tether herself to the world. “Happiness is,” she writes later, in 1925, “to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves.” At Asheham, she strings one paragraph after another; a way of watching the days accrue. And as she recovers, things attach themselves: bicycles, rubber boots, dahlias, eggs.

***

Between 1915 and her death in 1941, Woolf filled almost thirty notebooks with diary entries, beginning, at first, with a fairly self-conscious account of her daily life which developed, from Asheham onward, into an extraordinary, continuous record of form and feeling. Her diary was the place where she practiced writing—or would “do my scales,” as she described it in 1924—and in which her novels shaped themselves: the “escapade” of Orlando written at the height of her feelings for Vita Sackville-West (“I want to kick up my heels & be off”); the “playpoem” of The Waves, that “abstract mystical eyeless book,” which began life one summer’s evening in Sussex as “The Moths.” There are also the minutiae of her domestic life, including scenes from her marriage to Leonard (an argument in 1928, for instance, when she slapped his nose with sweet peas, and he bought her a blue jug) and from her relationship with her servant, Nellie Boxall, which was by turns antagonistic and dependent. Most of all, the diary is the place in which she thinks on her feet, playing and experimenting. Here she is in September 1928, attempting to describe rooks in flight, and asking,

“Whats the phrase for that?” & try to make more & more vivid the roughness of the air current & the tremor of the rooks wing slicing—as if the air were full of ridges & ripples & roughnesses; they rise & sink, up & down, as if the exercise rubbed & braced them like swimmers in rough water.

But the “old devil” of her illness was never far behind. If, in her diary, Woolf could compose herself, she could also unravel. There are jagged moments. She could be cruel—about her friends, or the sight of suburban women shopping, or Leonard’s Jewish mother. And she felt her failures acutely. In the small hours, she fretted over her childlessness, her rivalries, the wave of her depression threatening to crest.

Her diaries’ elasticity, their ability to fulfill all these uses, is, as Adam Phillips notes in his foreword to Granta’s new edition of the second volume, evidence of “Woolf’s extraordinary invention within this genre.” The Asheham diary was one of her earliest experiments in the form. She was reading Thoreau’s Walden and Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere journals, marvelling at those writers’ capacity for a language “scraped clean,” their daily lives, and their descriptions of the natural world, intensified for the reader as if “through a very powerful magnifying glass.” Yet the life span of her own rural diary was short. In October 1917, upon her return to London, Woolf began a second diary, written in the style of those which preceded her breakdowns. Her Asheham diary she left stowed away in a drawer. (When, the following summer, she reached for the notebook, writing in both concurrently, it was the only time she kept two diaries at once.) In her other diary, the ligatures loosened, and she began developing the supple, longhand style she would use for the rest of her life. Her concision was gone, though her Asheham diary had left its mark. In London, she continued to open each day with her “vegetable notes”—an account of her walk along the Thames, or a note about the weather. And she described everything she saw with the curiosity and precision of a naturalist’s eye.

***

In the long and often fraught history of the publication of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, no one has known what to do with such a sporadic notebook, seemingly out of sync with the much fuller diaries that came before and after it. Following Leonard’s selection of entries for A Writer’s Diary, which was published in 1953, work on the publication of her diaries in their entirety began in 1966, when the art historian Anne Olivier Bell was assisting her husband, Quentin Bell, in the writing of his aunt’s biography. As parcels of Woolf’s papers arrived at the couple’s home in Sussex, Olivier—the name by which she was always known—realized the scale of the project, which involved organizing, noting, and indexing 2,317 pages of Woolf’s private writing. She leaped at the chance, “largely,” she later reflected, “because it gave me an excuse to read Virginia’s diary, which I longed to do.” So began nearly twenty years of scholarship, culminating in their publication, in five volumes, by the Hogarth Press, between 1977 and 1984.

It was a laborious process. Working first from carbon copies—which needed to be pieced back together after Leonard had gone through them, with scissors, to make his selections —and later from photocopies (the manuscript diaries were moved in 1971 from the Westminster Bank in Lewes to the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library), Olivier set about constructing her “scaffolding”: she took six-by-four-inch index cards, one for each month of Woolf’s life, and recorded on them the dates in that month on which Woolf had written an entry, where she had been, and who she had seen. Olivier spent long hours in the basement of the London Library, consulting the Dictionary of National Biography for details of one of Virginia’s friends, or decaying editions of the Times for a notice about a particular concert at Wigmore Hall. And there were decisions to make. What to do with Woolf at her most unkind, or snobbish? Olivier devised some basic rules for inclusion: she pinned a piece of paper above her desk that read ACCURACY / RELEVANCE / CONCISION / INTEREST. She decided there was little point in upsetting those friends still living, and cut any particularly unflattering descriptions. And Woolf’s Asheham diary—“too different in character” from the other diaries, she noted, and “too laconic”—didn’t merit publishing in full. The second volume, from the summer of 1918, was omitted completely.

This summer, Granta has reissued Woolf’s diaries and billed them as “unexpurgated,” a promise that has caused no small stir among Woolf scholars, who had thought Olivier’s editions were complete. The new inclusions are, in fact, mostly minor: a handful of comments about Woolf’s friends, written toward the end of her life, including an unpleasant description of Igor Anrep’s mouth. Otherwise, Olivier’s volume divisions remain unchanged, her notes and indexes intact; it is as much a reproduction, and a celebration, of her scholarly masterpiece as of Woolf’s diaristic eye. The most significant addition is Asheham. For the first time, Woolf’s small diary—the last remaining autobiographical fragment to be published—appears in its entirety. And yet those readers turning to Granta’s edition for details of Woolf’s country life in 1918 must skip to the end of the first volume, and look for her diary beneath the heading “Appendix 3.”

***

Appendixes can be awkward, unwieldy things. They serve a scholarly function—to present information deemed unsuitable for the main body of a text, like an attachment, or an afterthought. And an appendix is an especially odd place for a diary, putting time out of sequence, disrupting the “current”—as Woolf liked to call it—of everyday life. The remaining paragraphs of the Asheham diary have been relegated behind the main text; they sit quietly, unobtrusively, documenting a life as minute and domestic as before. Returning to the house in 1918, Woolf records her days, the winter melting into spring—the last of the diary, and the war. Out on her walks, she sees “a few brown heath butterflies,” the air “swarming with little black beetles.” She spends afternoons on the terrace, the sun hot, “had to wear straw hat,” and in the evening, she and Leonard sit “eating our own broad beans—delicious.” There are more local intrigues: the coal from the cellar goes missing, a mysterious plague kills the farmer’s lambs. Day by day, she watches a caterpillar pupate. The news is better from France. Still, the German prisoners work in the fields. “When alone, I smile at the tall German.” But her entries are thinning. By September, there is “nothing to notice” on the Downs, or “nothing new.” Even the butterflies are less brilliant—a few tortoiseshells, some ragged blues. Finally, toward the back of the notebook, she lists the household linen to be washed.

Her attention had begun shifting elsewhere. In London, she was becoming intensely preoccupied with the Press, and with writing shorter things, impressions and color studies—the pieces that will make up her first book of stories, Monday or Tuesday, published in 1921. And yet, if one looks closely, one can see the diary in some of these stories; something like an underpainting.

Take, for instance, Katherine Mansfield’s visit to Asheham in August 1917. The diary’s summary of Katherine’s visit is brief: her train into Lewes was late, so Woolf bought a bulb for the flowerbed; later, the two writers walked on the terrace together, an airship maneuvering overhead. Yet from letters, we know that the manuscript for Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” was almost certainly brought out. In it, we can see the imprint of Asheham, its reversal of scales, its teeming insect life. In the story, which was published in 1919, human life takes place off center, in the murmur of conversation wafting above the flower bed, while the “vast green spaces” of the bed and the snail laboring over his crumbs of earth loom largest of all. The story, though set in Richmond, captures the atmosphere of Asheham. Its form, like the other stories in Monday or Tuesday, owes much to the episodic structure of her diary, in which impressions are hazy, words come and go, and attention is both microscopic and abstract. And its authorial presence mirrors the one we find in the notebook—a writer who is both there and not there, looking and noticing.

Toward the end of 1918, as Woolf’s convalescence comes to an end, so does her Asheham diary. Back in London, she muses on the project she has kept going for two years: “Asheham diary drains off my meticulous observations of flowers, clouds, beetles & the price of eggs,” she writes in her other, longer diary, “&, being alone, there is no other event to record.” It has served its purpose, paving a way back to writing after illness, of nursing her attention back to life. Though it was later forgotten, it always stood for one of her quietest and arguably most important periods, between her first attempts at writing and those fleeting experiments which determined the novels that came afterward. And it continued to be a storehouse for images to be drawn upon later—her nephews, Julian and Quentin Bell, carrying home antlers, like those in the attic nursery in To The Lighthouse; a grass snake on the path, like the one Giles Oliver crushes with his tennis shoe in Between the Acts; a continuous stream of butterflies and moths.

Harriet Baker is a British writer. Her work has appeared in the London Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, and Apollo, among others. Her first book, Rural Hours: The Country Lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamond Lehmann, will be published by Allen Lane in March 2024.

June 20, 2023

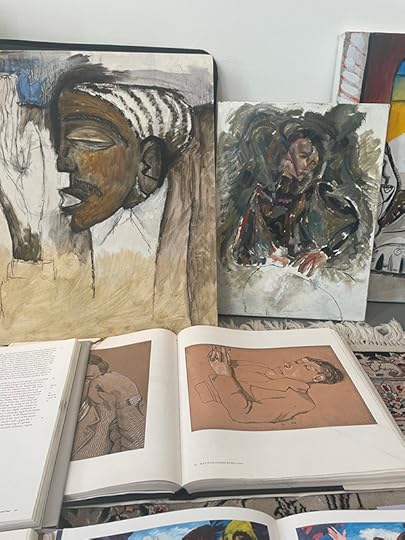

The Cups Came in a Rush: An Interview with Margot Bergman

Margot Bergman’s studio. Photograph courtesy of Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago.

Do cups have souls? If you look at Margot Bergman’s portfolio in our Summer issue, you might be tempted to say yes: the cups she has painted, from various vantage points and in bright colors, seem filled with life. Bergman, who was born in 1934, has been painting for nearly her whole life. She is best known for her series Other Reveries, which features collaborative portraits painted over artworks she has saved from flea markets and thrift stores. Each painting is layered with decisive, bold paint strokes, revealing a face latent with layers of emotions. They are at once beautiful, frightening, humorous, and welcoming. Who knew that cups could contain similarly human emotion? We talked about the joys of painting, the female form, and of course, what drew her to cups in the first place.

—Na Kim

INTERVIEWER

Much of your work revolves around faces, and especially female figures. When did start painting these?

MARGOT BERGMAN

In the fifties. The artist R. B. Kitaj was painting very flat paintings. I was attracted to his style. I began to paint like that. I still have some of those paintings in the basement of my home, left over from the fifties—a series of flat paintings of naked women. They were very flat, very unsexual, though the women were butt naked, with their backs turned to the viewer. At one point, the city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, wanted some of my paintings for the hallway of a government building. They were these Kitaj-like paintings of women, all naked, their backs turned, with what look like bits of collage randomly placed in the paintings. There was a controversy, and the paintings made it in to the newspaper in Milwaukee, because some women’s group had demanded for them to be taken down.

INTERVIEWER

What happened?

BERGMAN

They were taken down. It was the fifties. I thought it was so funny. And kind of outrageous, but mostly I thought it was funny. Strange, funny, and uninformed.

INTERVIEWER

These women with their backs turned, were they all the same woman, or different women? Who were they?

BERGMAN

I have no idea. But they did not represent me. They were very planiform. There was no voluptuousness to them. There was no shading. They really revealed form. They had shapes, but no real substance. And they were looking out into a courtyard, and the coloring was a bit Impressionist. They were really not expressionistic in any way. I would say that I was influenced by Pierre Bonnard at this time—that was probably my first true love of an artist’s work.

Margot Bergman’s studio. Photograph courtesy of Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago.

INTERVIEWER

What about Bonnard was particularly inspiring to you?

BERGMAN

I thought his work was beautiful. I thought it was intimate. Later in life, what I’ve come to know is that there was an intimacy to his work that I was not seeing in the work of other artists. And that’s probably what drew me to him.

INTERVIEWER

What led you to start painting the cups that are featured in our Summer issue?

BERGMAN

I had started another body of work that wasn’t working. I was disappointed in it. It had to do with bricks, both rigid urethane ones and children’s building blocks. They were three-dimensional, and I was trying to do paintings of the bricks so that the works on paper were geometric forms. I just could not make them work. So I tore one of them up. I tore up a piece of paper in my frustration, and then I just made a painting of a cup on one of the scraps. God knows. God knows why.

Perhaps now I can look at it and say that the original work had so much geometry, so many hard lines, that I needed a circle. But that really did not go through my mind. My process is very intuitive. I just found myself making a circular form, and the form that came out was a cup. Then the cups came in a rush—I’ve now done seventy of them. It was one after another, after another, after another, just pouring out of me.

INTERVIEWER

I wanted to talk about another important body of your work—your found collaborative paintings, which are portraits overpainted on paintings you often find in flea markets and thrift stores. There’s something so haunting about them. The faces really stare back at you. Do you ever think of real people when you’re painting them, or are they people who come from your mind?

BERGMAN

No, I do not think of them as real people. But when they come out, they frequently have names. There is something in my subconscious that finds a name. I don’t analyze it. Almost always, after a portrait is done, I know the figure’s name. It’s like the painting itself: it just is.

Margot Bergman’s studio. Photograph courtesy of Margot Bergman.

INTERVIEWER

What led you to begin painting over the works of others?

BERGMAN

Before I started making those paintings, I was embedded in the world of art. I was in the galleries. I had lived in New York. I walked the walk and did the talking, and I realized that I was uninspired by the things I was making and didn’t like what I was seeing on the walls either. These works had no heart for me. And when I would go to a flea market, it was all heart. There were these inexperienced artists who were giving everything to make something that they truly cared about. I was drawn to that, so I would bring their work back to the studio. At first, I felt it was a no-no to paint on them, so I didn’t, but I kept collecting them. And then, one day, I just saw a face in one of them, and I painted it on top. That was very satisfying. For about ten years, I worked on that body of work. I had to go out and hunt down these kinds of paintings, which is not an easy thing to do. And nobody wanted the paintings I did with them. I tried in Chicago to have them be seen. Until John Corbett came along, many years later, nobody would show them. I had pulled myself away from whatever I thought was the art world, and I was making strictly for myself. I love them. I love doing it.

INTERVIEWER

You talked a little bit about the difficulties of being an artist. What would you say were some major roadblocks for you?

BERGMAN

It’s trite to say it, because everybody knows it. But let’s start with being a woman. I had children. I was married. I lived in the suburbs of Chicago in the fifties and I had a husband who could support me. I was attractive. I had no network because I didn’t finish my degree at the Art Institute—I got married when I was twenty-one, and my husband was in service and I followed him. How many things worked against me there? I was not part of anything, and I was different, then. But it didn’t stop me from painting, ever, ever, ever, ever. I worked like hell. I was always working. I think we’re working even when we’re not working. I think when we walk in our space and we sweep the floor, we are working. It is something that’s inexplicable.

INTERVIEWER

What part of the painting process would you say is your favorite, if you have one?

BERGMAN

I like pencils. I like paint. I love paint. I love paint. I love mark-making. I love the end, when one can see something that one could say is complete.

INTERVIEWER

How do you know when a painting is done?

BERGMAN

Sometimes I’ve been right and sometimes I’ve been wrong. I’ve often thought, Can I make it better if I keep going? It’s a well-known fact that artists can leave their studio or workspace, think they have completed a painting and are satisfied with it, and come back the next day and say, “Oh my gosh, that’s not nearly what I thought it was.” So, how do we know? We don’t always.

INTERVIEWER

Is painting intuitive to you? Do you find it difficult?

BERGMAN

I don’t take myself too seriously until I need to be serious. I like playing. I don’t mean that I am not working seriously. I am looking hard, but I’m also having a very good time. Painting is a very joyful process for me. And even though it can have dark undertones, for me, painting is the unearthing of whatever is there for me to find. That’s just intuitive.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you think this curiosity and urge to create comes from?

BERGMAN

When someone comes to me and says, “I just traveled to India, and I did this, and I did that,” I think to myself, I just traveled on my own adventure. I love adventure, and I equate what’s happening to me on the canvas with a journey. My journey has no map.

Na Kim is the art director of the Review.

June 16, 2023

On Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Photograph by Dan Moore.

Cormac McCarthy’s work means a lot to me, though when I try to explain exactly what, I find myself unusually stymied; my affinity for him doesn’t make all that much sense to me. What connection do I have with the landscapes he conjures? What knowledge do I have of the kind of violence that is the subject and the fabric of many of his books? What place do I find in a world that is, among other things, nearly entirely masculine, hostile, rife with true desperation? The answer is none—unlike with much of my reading, I do not seek a mirror in McCarthy’s worldview—and yet there is something in its aesthetic articulation that has always resonated with me. (I have a curious memory of reading The Road over my mom’s shoulder when I must have been about ten.) I have a passage from All The Pretty Horses saved on my desktop, which I have revisited often and send around now and again, and which I cannot quote in full here but which ends:

The water was black and warm and he turned in the lake and spread his arms in the water and the water was so dark and so silky and he watched across the still black surface to where she stood on the shore with the horse and he watched where she stepped from her pooled clothing so pale, so pale, like a chrysalis emerging, and walked into the water.

She paused midway to look back. Standing there trembling in the water and not from the cold for there was none. Do not speak to her. Do not call. When she reached him he held out his hand and she took it. She was so pale in the lake she seemed to be burning. Like foxfire in a darkened wood. That burned cold. Like the moon that burned cold. Her black hair floating on the water about her, falling and floating on the water. She put her other arm about his shoulder and looked toward the moon in the west do not speak to her do not call and then she turned her face up to him. Sweeter for the larceny of time and flesh, sweeter for the betrayal. Nesting cranes that stood singlefooted among the cane on the south shore had pulled their slender beaks from their wingpits to watch. Me quieres? she said. Yes, he said. He said her name. God yes, he said.

The surprise of all this tenderness—brutality and tenderness always strangely twins, never far from each other, never balanced. There is almost nothing more moving than that.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

When I was around fourteen, backpacking in New Mexico’s Cruces Basin Wilderness, not far from where I grew up, I was made to believe that I was going to be attacked by a pack of wolves. The elaborate prank depended on recordings of howling played from a hidden speaker. It may have been cruel, but I was stupid and city-reared; though wolves once roamed that high, forested country, as they did the whole of what is now the United States, we hunted them to near extinction by the thirties, when Cormac McCarthy was born. If Mexican wolves—lobos, those borderland animals that McCarthy described in his novels as “themselves the color of the desert floor,” spectral beings that observe “old ceremonies,” “old protocols”—had somehow crept up from their more southern habitat in legion, I’m sure conservation groups would have citizen’s-arrested my party for getting too close. And, most importantly, what would a wolf want to do with me? Nothing. But I was still terrified. We rimmed a campfire among pines and aspen. The flames emitted light that stopped at the bank of a narrow nearby creek, and the darkness that lay on the other side formed a curtain through which I briefly believed something murderous would emerge.

Inside of the prank and before its punchline was, in a way, a small story about McCarthy’s American West, where whole worlds are destroyed and the open maws left behind overcome us—where the phantom wolf call creates a black hole. McCarthy wrote figures, like Judge Holden, who were the genocidal tycoons of that brutal machine and greased its wheels. Others, like Billy Parham, became its more indirect, melancholic grist. The operatic violence McCarthy rendered on the page to give linear shape to this cosmic ruination distracts some readers, who think that gore is the end to his logic. But he always wondered what lay beyond the desolation. He wrote about love all the time, for one. It never really saved his characters, but it allowed their histories to braid into intertwined fates; still doomed, but larger than a lonely soul. In his final, stunning books, especially in The Passenger, he was exhausted with language while wielding it expertly, steering two cursed siblings toward mathematics, music, and the unconscious in search of ideas that might offer redemption in the atomic age. They come up empty-handed.

There are no wolves in Cruces Basin, of course, and now McCarthy is dead. The spaces left by these kinds of endings cannot simply be filled. They are instead gaping openings that in turn invert and spew outsize, defiant materials: fear, as well as stories.

—Elena Saavedra Buckley

The first time I opened a Cormac McCarthy novel, I was twenty-six, living alone by the beach, unemployed, passing evenings drinking beer with a couple who made camp in a Chevy Suburban at the dead end of the block before the stairs to the boardwalk. The stark reality of Suttree’s gang of Knoxville misfits revealed a perspective more outré than I was prepared for: beyond bohemian in its societal disdain, and finding fellowship with the indigent, the criminal, the addicted, the cruel, and the deranged. Over the following year, I read my way through his complete oeuvre. Lyrically poignant and ideologically fierce, McCarthy eschewed classification. He had no contemporaries. He wasn’t part of a movement. And the anecdotes of his life—building fireplaces from the stones of James Agee’s childhood home, plotting to furtively reintroduce wolves to the Arizona desert, changing his name from Charles so as not to be mistaken with the dummy of a famous ventriloquist of the era—imbue the author with a near-mythological status as cabalistic as the stories he penned.

Frequently, his work gives an impression of collaboration with land and history: endemic folklores drawn out of America’s bedrock, reflecting the many faces of humanity that have torn it asunder. In Child of God, scenes of poverty turn to murder and necrophilia, pressing beyond the pale without ever feeling cheap or contrived. The horrific, frank violence of Blood Meridian—based on fact, and partly allegory for the Vietnam War and colonial exploits of that millennium—probes man’s capacity for evil. Though he’s best known for the tangled and grisly, McCarthy was just as effective in sentimental romances (The Border Trilogy) and crime thrillers (No Country for Old Men). His gift for dialogue is apparent in the humorous and unsettling catechism of The Sunset Limited, a two-hander play, as well as his final novels. Toward the end of his life, he turned evermore to dreams, abstract math, physics, the unconscious, and the beyond.

McCarthy, in short, could do anything, and he seemed to view this as a responsibility. His rhetoric was bold and sociopolitically urgent, yet aligned solely with his own vision for the world—one which demanded constant growth and expansion and awe. From All the Pretty Horses:

He rode with the sun coppering his face and the red wind blowing out of the west across the evening land and the small desert birds flew chittering among the dry bracken and horse and rider and horse passed on and their long shadows passed in tandem like the shadow of a single being. Passed and paled into the darkening land, the world to come.

—David Fishkind

Head Studies: A Conversation with Jameson Green

In Jameson Green’s studio. Photograph by Na Kim.

Earlier this year, the Review commissioned the artist Jameson Green to paint a series of writers’ portraits for our new Summer issue—an idea Green came up with after looking through our archives and being particularly intrigued by a portfolio of Picasso’s drawings published in 1987. What he gave us is a delightful collection of what he calls “head studies,” renderings of famous writers from our archive—some recognizable, some less so—that capture, loosely, something of each subject’s essence. And, like much of Green’s other work, Writers borrows from various art historical styles—you’ll find, for instance, a Picasso-esque Percival Everett (or is it Edgar Allan Poe?) and Shirley Hazzard in the style of Vincent Van Gogh. Over the phone, we talked about his childhood obsession with cartoons and about the special attention portraits require, and I tried to guess who was who.

INTERVIEWER

Do you consider yourself a portraitist?

GREEN

I don’t paint portraits regularly. But when I was learning to paint, I studied artists like Alice Neel and John Singer Sargent closely. They’re very different stylistically, but there’s a relationship in terms of their sensitivity to the humanity of the sitter. Those are people I call genuine portrait painters—people like them and Diego Velázquez. The overall essence of the people he paints feels real. You need to have a special kind of attention to that essence to be a great portrait painter. I can get it on some occasions, but not always.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever painted someone you know well?

GREEN

Not in a portrait sense. I think a portrait is based on a singular sitting. I have painted my wife on multiple occasions where she has served as a character or has inspired one. So many of the figures in my paintings are theatrical, both in their presentation and their function. They’re more like actors on a stage than they are unique individuals. I’m more interested in the people in my head than I am in the people in my life, when it comes to making something.

INTERVIEWER

So how about the writers you painted for the portfolio for the Review? Are all of them real? I’ve been trying to do some guessing. Is that Edgar Allan Poe, with a raven on his shoulder?

GREEN

I don’t really remember. While I was working, I flipped through old books and old issues of The Paris Review, and looked at images of different writers. Sometimes someone would strike me, and I’d think, Oh, they could be fun to paint. Even then, I didn’t really use the writers’ photographs. That’s why I called them “head studies” and not portraits. A portrait requires some level of delicacy in terms of intention. You serve the sitter—to a degree, at least. You are playing with their likeness, but in a lot of ways it’s sensitive to the person involved. In this case, I was serving the paintings.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell me a little bit about the styles of the head studies?

GREEN

I was thinking a lot about the paint application in Picasso’s late paintings. He was using house paint and very, very fluid oil paint applied quickly. I was trying to understand how to work with that level of thinness. Normally my brushstrokes are meatier and more evident. This time, I was using a very thin application of really wet paint. It was a wet-on-wet process, bringing down a thin tone that was already rich and solvent, and then bringing in a limited number of colors to build on the form. I was allowing myself to paint over things, to move them out of the way. I’ve kept up this process, even after finishing the series for the Review. Before making these portraits, I typically used charcoal to draw a preliminary sketch, and then I would paint in response to it, on a dry surface. Now, I’m doing everything on a wet surface, which means I have to move at a particular pace to react while it’s still wet.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take to make these?

GREEN

I would say it typically took me only about an hour to make one. Once, I did seven in one day. In the end, I painted close to thirty portraits. But some of them were completely not of writers at all. I would think, Okay, I like how I did this one—I’m going to do another one and I’m not going to act like it’s a person at all, it’s just going to become my own thing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember the first things you were interested in drawing?

GREEN

I drew my own cartoons. I would make up characters based on my classmates when I was younger. At school, I put my own comics out in the classroom for people to read. I drew everything, all the time. I drew on scrap pieces of paper and often got in trouble for it—my dad complained that he couldn’t put anything down around me, because I’d start scribbling on the corners of his mail, on important receipts. But my mother preferred that to me drawing on the walls in my house.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

How did you develop your style? Who were some of your influences?

GREEN

When I was first in high school, I didn’t know much about artists. I knew about Jacob Lawrence, because my aunt had a few prints of his work, and I was interested in older illustrators— people like Norman Rockwell, J. C. Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish. I looked at these illustrators as being at the top of the mountain of technical control.

Then I got my hands on a book of Picasso’s work from one of my friends, who said, “Look at what he was doing at our age.” I was always really competitive, so naturally I thought, Well, he can’t do better than me—I have to figure this out. That started my deep dive into different visual languages. I began paying attention to the haptics of drawing and trying to really understand the nuances of how a line can make you feel. I explored different styles and approaches because I wanted to be able to have those tools in my back pocket. Personally, I don’t care about getting too close to another artist’s wheelhouse. I’m from the school of Picasso, where if you like something and you respond to it, you steal it. I had this musical analogy in my head—I had been taught, You have to learn the scales so that if you ever come to a moment of improv, you can act without thinking.

INTERVIEWER

Do you listen to music when you’re working?

GREEN

I usually have a handful of songs for each painting that I’ll listen to on repeat. When I was working on the portfolio for the Review, because I was exploring different paint styles, those choices were all based on rhythm.

My family is very musical—my mom was a music teacher, and my brother is a composer and a violin instructor. My younger sister just finished up at Yale, where she was part of an a cappella group. I, on the other hand, was cool with mostly just listening to music. But having that background has affected how I see colors and responded to imagery. Images, to me, always had a sound. When I make a painting now, it’s like the image gets shaped through a sound. It’s like I can listen to music coming into my head, and the color and form and composition start to animate themselves right before I put them on the canvas.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

How many paintbrushes do you have?

GREEN

I am not the cleanest person. I’ve seen artists who are very organized with their brushes, and take very good care of them, as they should. I don’t. My brushes are often left in some solvent, and they become pretty crappy pretty fast. I have quite a few of them, maybe thirty—though compared to other artists whose studios I’ve visited, that’s not very many. But the thing is, you get all these brushes and you end up using only ten of them.

Photograph by Na Kim.

Camille Jacobson is The Paris Review’s engagement editor.

Jameson Green is represented by Derek Eller Gallery.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers