The Paris Review's Blog, page 49

August 9, 2023

How the Booksellers of Paris Are Preparing for Next Summer’s Olympics

Photograph by Jacqueline Feldman.

“With a diving suit and helmet,” said Yannick Poirier, the owner of Tschann bookstore on the boulevard Montparnasse, where he has worked for thirty-five years, “and with dark glasses, earplugs, and a plan for survival and retreat to the countryside. I hate sport. That’s personal, but I hate sport, and I have a horror of circus games, and, how to put this. You are American? So you know Jean Baudrillard. For us he was a friend, Jean Baudrillard. So he has The Consumer Society, like Debord has The Society of the Spectacle, and all that sticks to us like shit. No, frankly, the Olympic Games—for me they leave me neither hot nor cold. They leave me totally indifferent.”

“There are books about sport,” offered a bookseller at Le Genre urbain, “but they are very distant disciplines, all the same.”

“If there are any,” they said at Le Monte-en-l’air, “and if they are good, we have them.” This clerk, like their counterpart at Le Genre urbain, was “against” the Olympics (“in a personal capacity,” they added at Le Genre urbain). Both bookstores, singled out for questioning out of the city’s hundreds, are in the twentieth arrondissement.

“We’ll of course have a few books,” they said at Les Traversées, “but in a corner.”

“We are not going to decorate the bookstore,” said Anne-Sophie Hanich, managing Les Nouveautés.

“The Olympic Games,” said Gildas, his first name, at Les Traversées, which is half-buried in the hill of the rue Mouffetard (“I detest my family name”), “are not the most important thing.”

“We have other things to think about,” they said at Le Merle moqueur, on the rue de Bagnolet. “We have other problems right now.”

“Literature, first of all,” Gildas went on. “And then, well. Thought, imagination, reflection, beauty, love.”

“The problem of getting clients to come in. Social problems.” At Le Merle moqueur, the clerk wrapped a book for gifting.

“You think an independent bookstore isn’t a business like any other?” Olivier Delautre at La Cartouche, where his own trade has been, for sixteen years, in antique and used books, was leaning back in a low chair, letting it tilt. As a bouquiniste, Delautre sets himself apart from peddlers of new books, whom he sees as profit-minded. “These are small people,” he said, “who are there to carry boxes.” His colleagues who sell out of iconic boxes along the Seine have mobilized against a prefectural injunction to remove themselves ahead of next year’s opening ceremony (for the reason, the prefecture told them, of “terrorism” risk). “I sell principally old books,” Delautre said, “published at a time when sports did not exist.”

At the Librairie des Abbesses, Marie-Rose Guarniéri, who had been described to me at Les Traversées as the grand dame of the Parisian bookstore, told me to come back in fifteen minutes and, by the time I did, was in a fury. I had been expecting her to speak to me of her own métier without making an appointment, she accused. “You must make an appointment,” she repeated. “I am not some button you can just push,” she said.

“At the moment it’s still a little early,” said Chafik Bakiri, the owner of Equinoxe, where “eighty percent” of stock is secondhand books. “Currently I don’t have any ideas.”

“I know that during the Olympic Games we will do strictly nothing other than what we’ve been doing for ninety years,” said Poirier.

“Nothing,” Gildas said. “And so it’s simple.”

“Old posters,” Bakiri mused. “Objects, medals, I don’t know.”

“Maybe we’ll do one window about sports,” said Hanich. “Maybe some French flags.”

“I live in Saint-Denis,” they said at Le Monte-en-l’air, “and we’ll be particularly affected.” The suburb just north of Paris, its name—like the name of the poorest department in mainland France, the 93, where it is situated—is in wide use as a metonym for institutional neglect and the suffering of whole communities; the national stadium, located there, will be one of the principal sites for the 2024 Summer Olympics (“the biggest event ever organised in France,” according to official messaging). Leaving Le Monte-en-l’air, I saw the window was lined by copies of On ne dissout pas un soulèvement, Seuil’s new release by forty authors writing in support of Soulèvements de la Terre, a collection of groups in France organized around local environmental causes. In the 93 in Aubervilliers, local activists have been partially successful in defending community gardens against their demolition to make way for, among other things, the Paris Olympics Aquatics Centre.

“Now we know,” said Xavier Capodano, after making me a coffee, espresso, in an office at Le Genre urbain, which he founded. (“Relax,” he said as we went back there. “I’m not nice, but I’m not going to eat you.”) “Thirty or forty years ago, we didn’t know where we were going.”

Capodano was referring explicitly to the link between runaway construction and “the planet’s quality of life.” It was a summer of, once again, high temperatures everywhere (with the notable exception of Paris, where it has rained almost every day); of service outages along the Paris metro for planned work (“The Line 5 is closed,” I complained to a friend, “between Gare du Nord and the rest of the world”); and of, in this city definingly, the death of Nahel Merzouk, seventeen, shot in the chest by a Paris-region policeman during a traffic stop. “I’m not convinced,” I heard, “of the book’s role in the revolution.” This was from a worker at a bookstore in the east of Paris who asked me to identify it in that way only. They had the sense, they said, that their “role in society,” their part in its duties of care, had been greater when they were on unemployment. They had time then to participate in a neighborhood group like a soup kitchen, which was organized horizontally (so that “there wasn’t any distinction” between volunteer and beneficiary). Not anymore. “We’re a business,” they said of the bookstore, “before anything else.” And so the store retained a certain “expressive space” in being able to, say, “do a bit of publicity for Soulèvements de la Terre,” but to the worker this did not seem, at all times, adequate. We spoke in a courtyard of modern, unfancy construction, unplanted. “The moments of radical transformation of society I’ve had the chance to see have been more in its insurrectional phases,” they said, “and I haven’t necessarily seen insurrectional phases opened up immediately from reading books…”

“In the abstract,” said Anne, “literature can do anything it likes.” A retired sociology professor, she was volunteering at Quilombo, a “bookstore of the extreme left, anarchist in fact.”

“It’s not my place to judge what literature should or shouldn’t do,” said Capodano. “Literature does what it wants. It lives its life.”

“For me,” said Poirier, as if demonstrating a last, important capacity of literature, “it’s as if the Olympic Games did not exist.”

Jacqueline Feldman is a writer living in Massachusetts. Precarious Lease, her book about Paris, is forthcoming from Rescue Press.

August 8, 2023

Watch Jessica Laser Read “Kings” at the Paris Review Offices

On August 3, the poet Jessica Laser visited the offices of the Review in Chelsea and treated us to a reading of her poem “Kings,” which appears in our Summer issue. The poem, which our poetry editor Srikanth Reddy described as a “dreamy, autobiographical remembrance,” includes memories of a drinking game she used to play in high school on Lake Michigan, and is charged with eros:

… You never knew

whether it would be strip or not, so you always

considered wearing layers. It was summer.

Sometimes you’d get pretty naked

but it wasn’t pushy. You could take off

one sock at a time.

A perfect poem to read or listen to in the dog days of August, as summer flings might be coming to an end!

FROM “LAUREL NAKADATE AND MIKA ROTTENBERG,” A PORTFOLIO CURATED BY MARILYN MINTER, FROM ISSUE NO. 197, SUMMER 2011.

The Paris Review Print Series: Shara Hughes

Shara Hughes, The Paris Review, 2023, etching with aquatint, spit bit, soft ground, and drypoint on Hannemühle Copperplate bright white paper, plate size 18 x 14″, paper size 27 x 22″. Made in collaboration with Burnet Editions. Photograph courtesy of Jean Vong, © Shara Hughes and Burnet Editions.

Earlier this year, The Paris Review released a new print made by Shara Hughes. Hughes, who was born in Atlanta in 1981 and works in Brooklyn, New York, describes her lush, chromatic images of hills, rivers, trees, and shorelines, often framed by abstract patterning, as invented landscapes. The one she invented for the Review is striking in its rich color and vibrant dreaminess. We spoke to Hughes about her work this summer, touching on poisonous flowers, her unusual color palette, and landscape paintings.

Photograph by Elliot Jerome Brown, Jr. Courtesy of Shara Hughes and Pilar Corrias, London.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you find yourself drawn to botanical imagery and landscape?

HUGHES

Landscapes are accessible to most humans. Nature is something that is familiar but uncontrollable. I like the flexibility that painting landscapes provides—how quickly the mood can change. It feels really exciting and fluid. And the paintings can mimic people in a nonillustrative way. Like, a flower can stand on its own as a figure, or it can become a part of the whole scene. And I don’t have to be responsible for who exactly the figure is and what they look like. I don’t have to make a narrative about what the figure is doing in the landscape. Instead, I can ask the viewer to enter the landscape. Sometimes, they are the only figure there. This keeps the range of feeling and story vast.

Photo by Elliot Jerome Brown, Jr. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have favorite flowers to paint?

HUGHES

I don’t have a favorite flower to paint. And I’m not sure I care too much about what type of flower it turns out to look like. I do like symbolism and the meaning behind certain flowers but by the time I’ve finished the painting, it is not important to me if I’ve succeeded at rendering how that flower looks in real life. I’m more focused on the feel or the role of the flower within the painting. I wanted to paint poisonous flowers, so I researched what they look like. They look completely beautiful and no different than nontoxic flowers. If I want a flower to look toxic, it has to somehow feel that way when looking at the painting.

Photograph by Elliot Jerome Brown, Jr. Courtesy of Shara Hughes and Pilar Corrias, London.

INTERVIEWER

How do you choose the colors you’re going to use in a specific painting?

HUGHES

I don’t choose a specific palette before I start painting. It’s all intuitive and not predetermined. That keeps mystery and surprise in the process.

The Paris Review launched its print series in 1964 with original works by over twenty major contemporary artists. The series was underwritten by Drue Heinz, a literary philanthropist and former publisher of the magazine, and was directed by the American painter Jane Wilson, who also contributed a print. The series has since grown to include more than five dozen original works by acclaimed artists such as Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Helen Frankenthaler, Willem de Kooning, Marisol Escobar, and Sol LeWitt. MoMA purchased a full set for their permanent collection in 1967, and the series has been exhibited internationally. The print series was revived in 2022 with four prints by Rashid Johnson, Dana Schutz, Julie Mehretu, and Ed Ruscha. Hughes’s print is available for purchase, as are a number of the vintage prints.

August 7, 2023

Anti-Ugly Action

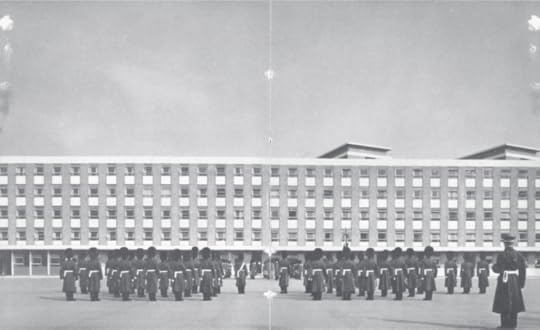

Chelsea Barracks, by Tripe & Wakeham, 1960–62. “An outstanding exposition of the fact that very big buildings can keep their scale without becoming inhuman.” All photographs by Ian Nairn.

It seems no less than highly appropriate that when Ian Nairn’s Modern Buildings in London first appeared in 1964 it was purchasable from one of a hundred automatic book-vending machines that had been installed in a selection of inner-London train stations just two years earlier. Sadly, these machines, operated by the British Automatic Company, were short-lived. Persistent vandalism and theft saw them axed during the so-called Summer of Love, by which time, and perhaps thanks to Doctor Who’s then-recent battles with mechanoid Cybermen, the shine had rather come off the idea of unfettered technological progress. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its malevolent supercomputer HAL 9000, after all, lay only a few months away. And so too, did the partial collapse of the Ronan Point high-rise (a space-age monolith of sorts) in Canning Town, East London—an event widely credited with helping to turn the general public against modernist architecture.

State House, Holburn, by Trehearne and Norman, Preston & Partners, 1956–60. “State House is a brave failure.”

As it was, Nairn’s book was published in the middle of a general election campaign that saw the Labour Party’s Harold Wilson become prime minister on the promise of building “a new Britain” forged in the “white heat” of a “scientific revolution.” And Modern Buildings in London is, for the most part, optimistic, or least vaguely hopeful, about what the future might bring—or definitely far more so than much of Nairn’s subsequent output. This is an observation rather than a criticism. In many respects, his growing disillusionment with the quality of new buildings in Britain was not unjustified. Modern Buildings in London finds Nairn at the peak of his powers; it is a book studded with as many pithy observations and startling thoughts as cloves in a ham. Not unlike D. H. Lawrence in his essays and travel books, Nairn’s sentences appear almost to jump-start, as if landing halfway through, punchy opinions falling instantly in quick-fire lines shorn of any unnecessary preamble or padding. Like in Lawrence, there is rage here, much of it directed toward the London County Council and their municipal architects and planners. Of the LCC’s handiwork in the Clive Street neighborhood of Stepney, he bluntly states: “I am too angry to write much about it,” before going on to argue that the old streets by comparison had “ten times more understanding of how people live and behave.”

Flats, St. James’s Place, by Denys Lasdun, 1960. “A masterpiece, and it could so easily have been a disaster.”

While Nairn is certainly unstinting in his admiration for Stockwell Bus Garage (“probably the noblest modern building in London”), in today’s age of corporate branding and slick advertorial content masquerading as journalism, that such a singular and original book was commissioned by no less a public body than London Transport seems almost a miracle. It joined a series of mostly decent if usually more plodding guides that the authority published in this era. Priced at five shillings a go, the list ranged from The Architecture of Christopher Wren in and near London to Visitor’s London to Sportsman’s London. There was even a move into fiction when it branched out with a Famous Five–style children’s adventure novel, The Tyrant King by Aylmer Hall, which was later turned into a TV series by Thames Television starring Murray Melvin and soundtracked with songs by Pink Floyd and the Nice. All these titles, though, fit within the decidedly Reithian tradition at London Transport to educate and inform its passengers, a tradition that had been established in the twenties and thirties by its thoughtful chief executive Frank Pick, under whose watch posters by Man Ray and Harry Beck’s diagrammatical tube map were authorized.

Bousfield Primary School, Old Brompton Road and The Boltons, by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, 1955. “One of the most imaginative new buildings in London, full of ideas and full of humanity too.”

These pocket guidebooks were expressly produced with a view to encourage off-peak leisure activity on its services, at a point when London Transport’s bread-and-butter revenues were under threat from rising private-car ownership and the slum clearance dispersal of the capital’s population to the suburbs and new towns. The latter, until their outer London Green Line bus service network was hived off in 1970, still fell within the company’s vast catchment area, which at that time, as Nairn notes, spread from “Bishop’s Stortford in one direction [to] Guildford in the other.” Nairn’s “in London” purlieu therefore takes in rather further-flung sights: from the bypasses at Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire (“an outstanding example of how to fit a modern road into mature English landscape”) to Gordon Secondary School in Gravesend, Kent (“Worth a visit, especially if you are familiar (or bored) with glass-wall buildings …”).

St. Paul’s, Bow Common, Burdett Road and St. Paul’s Way, Stepney, by Robert Maguire, 1958–60. “The only modern building in the London Transport area to reflect any real credit on the Church of England.”

Nairn had no architectural training, having studied mathematics at the University of Birmingham before joining the RAF as a pilot. It was as an aviator that he was tickled by the “concrete aeroplane … frankly done for fun” on the top of Great Arthur House in the Golden Lane Estate by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, and by the new terminal at Gatwick Airport by Yorke Rosenberg Mardall (a “Swiss watch of a building”). Nairn began contributing pieces on architecture to the Eastern Daily News while stationed in Norfolk. He eventually inveigled his way onto the staff of The Architectural Review after a concerted letter-writing campaign, and achieved almost instant notoriety at the age of twenty-four by authoring its special “Outrage” issue of June 1955. Billed by Nairn in the introduction as “a prophecy of doom,” the issue was a polemic against waves of recent development that, he argued, if left unchecked, would result in a Britain of “isolated oases of preserved monuments in a desert of wire, concrete roads, cosy plots and bungalows” with “no real distinction between town and country.” He dubbed this phenomenon “subtopia” and foretold that it would not be long before “the end of Southampton” looked like “the beginning of Carlisle” and “the parts in between” like “the end of Carlisle or the beginning of Southampton.”

Eastbourne Terrace, Paddington. C. H. Elsom and Partners 1958–60. “Proud and humble at the same time: this is what happens when you have a really difficult problem and look it straight in the eye.”

The idea of subtopia ignited debate about Britain’s built environment. In the popular press of the day, Nairn was anointed as architecture’s answer to the Angry Young Men (though “Outrage” preceded John Osborne’s genre-spawning play, Look Back In Anger, by well over a year). As a figure venting dissent to an emerging generation frustrated by the pace of change, Nairn would go on to inspire a fully-fledged protest group. After giving an incendiary lecture at the Royal College of Art in 1958, a band of students, among them the pop art painter Pauline Boty, were roused to found Anti-Ugly Action. Its members took to the streets to express their disgust with buildings they considered reactionary or offensive, in flamboyant fashion. They marched, for instance, on the new Kensington Public Library, a neo-Georgian effort by E. Vincent Harris, in period costume, accompanied by a Dixieland jazz band. They also carried a cardboard coffin emblazoned with a banner bearing the legend RIP HERE LEYTH BRITISH ARCHITECTURE to Barclays Bank’s new headquarters on the corner of Lombard and Gracechurch Streets, a portland stone–clad classical edifice by A. T. Scott and Vernon Helbing. Their impact was significant enough that both Nairn and the Anti-Uglies were cited favorably in the Labour Party’s (admittedly unsuccessful) 1959 election manifesto. (What Nairn himself made of this, as rather more of a Tory anarchist with a distinctly antiegghead and individualistic streak who claimed to be too unsophisticated to live in a Span house and distrusted Le Corbusier for his perceived contempt for ordinary people, I am not sure.)

Boundary Road Housing: Waltham House (flats) 1954 and Dale House (maisonettes), by Armstrong & MacManus, 1956. “Simple and very good—the simplicity of refinement of purpose, not poverty of invention.”

Sixty years have elapsed since Nairn wrote Modern Buildings in London. In many places, the city has changed beyond recognition, for good and ill. London was, in many respects, a far more parochial place back then. Nairn is ashamed on the capital’s behalf that “the only building in the book by a foreign architect of international reputation” is Eero Saarinen’s “pompous and tragic” United States Embassy in Grosvenor Square, a place largely remembered now as the setting of protests against the Vietnam War. Zidpark, Bowater House, and the LCC’s Clive Street blocks have all gone. Last orders have long since been called on the modernist interiors of the Hoop pub in Notting Hill Gate by Robert Radford, which Nairn maintained were “as elegantly planned as a suite of Adam rooms.” At the time of writing, 55 Gracechurch Street, the one-time home to the English, Scottish and Australian Bank, stands on the brink of its second complete rebuild since Nairn’s day. The first occurred in the nineties, when British postwar modernist architecture was at something of a critical low ebb. During that period, two more of Nairn’s favorites, Denys Lasdun’s Peter Robinson department store on the Strand (“a classic street front. You can pass it and always be refreshed”) and the Daily Mirror Building in Holborn (“one of the happiest modern townscape effects in London”) were destroyed, also.

Royal College of Art, Kensington Gore, by H. T. Cadbury-Brown, 1961–62, and Sir Hugh Casson. “As responsible architecturally as Imperial College is irresponsible, with a personality as strong as the Albert Hall, next door, yet without self-advertisement.”

The original cover for Modern Buildings in London, designed by Peter Robinson, depicted a crane with a London Transport roundel hanging from a hook. The image is curiously reminiscent of a gibbet. Nairn would come to grow increasingly anxious about what he saw as the high-handed remodeling of the capital and of Britain at large. In February 1966, he used his platform at the Observer to issue a 6,600-word screed titled “Stop the Architects Now” in which he castigated speculators, compliant political officials, and architects for their collusion in the demolition of decent older buildings and for banishing pedestrians to dank, subterranean concrete lairs. Nairn’s London, published later that year, came with a rejoinder urging its readers to seek out some of its entries before they fell to the wrecking ball. That ball, ironically, ultimately fell harder on the modern buildings he’d championed than on the Georgian and Victorian edifices he considered most at risk. To read Modern Buildings in London today is an act of time travel; the book is a ghost gazetteer whose coordinates map out a London that is lost, regardless of how many of the buildings Nairn describes are still standing. But it is no more outdated than, say, the Beatles’s “Love Me Do.” Nairn’s voice comes across loud and clear: insistent, urgent, and obdurate, and, on occasions, just plain wrong. What he has to say about the interaction between people and places is, today, as relevant as ever.

5 Cannon Lane, Hampstead, by Alexander Gibson, 1955. “Small, simple and beautifully detailed, in a labyrinthine part of Hampstead which has otherwise stayed firmly in the 1880s.”

From the introduction to Ian Nairn’s Modern Buildings in London, out in a reissue from Notting Hill Editions next month.

Travis Elborough is the author of many books, including Wish You Were Here: England on Sea, The Long-Player Goodbye, Through the Looking Glasses: The Spectacular Life of Spectacles, and Atlas of Vanishing Places, winner of Edward Stanford Travel Book Award in 2020.

August 4, 2023

August 7–13: What the Review’s Staff is Doing Next Week

Perseid Meteor Shower. Licensed under CCO 2.0.

This week, the Review‘s staff and friends are enjoying a drop in temperatures in New York City and the beginning of the August slowdown. Here’s what we’re looking forward to around town:

“Not Tacos” at Yellow Rose, August (6 and) 7: The downtown restaurant Yellow Rose is known for, primarily, tacos. (And really good frozen drinks.) But friend of the Review and meat purveyor Tim Ring recommends their upcoming collaboration with the Vietnamese food pop-up Ha’s Đặc Biệt that will explicitly not be tacos. Or will it? Their event poster features the words “Esto no es un taco” in Magritte-like font below what might or might not be a taco, depending on your definition.

Mark Morris Dance Group at the Joyce Theater, August 1–12: August is normally a quiet month for dance in New York City—for professional dance, at least. (We like to imagine that many people are dancing on their own.) But with the American Ballet Theatre and the New York City Ballet on hiatus, our engagement editor, Cami Jacobson, recommends seeing the Mark Morris Dance Group at the Joyce. This series will include some of Morris’s lesser-known pieces and be set to live music, in what Jacobson describes as an “unusually small, intimate theater” for seeing dance.

An overnight trip to the Irish Pub in Atlantic City, anytime: The Review’s Pulitzer Prize–winning contributor, friend, and Atlantic City expert Joshua Cohen writes in: “The Irish Pub, in Atlantic City, is the best bar I’ve ever slept at. But really, you can use their rooms for anything. At fifty dollars a night, the only thing cheaper is the beach, which is down the block.”

Lee Krasner: Portrait in Green at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in East Hampton, August 3–October 29: The only canvas that Lee Krasner painted in 1969 will be on view at the Pollock-Krasner House for nearly three months. Like many of Krasner’s best works, it is large-scale, gestural, and moving in the depths of its color. The exhibition also includes a series of stunning, rarely seen photographs of Krasner at work, and some works on paper. Visiting requires a train trip from the city, but even the house itself is worth it if you’ve never been, says our web editor, Sophie Haigney. Make sure to book a reservation in advance.

The Nuyorican Poets Café’s “Love Songs” poetry night at the International Center of Photography, August 10: This night of readings and performances by a group of poets affiliated with the Nuyorican Poets Café comes recommended by our associate editor, Amanda Gersten, but the title speaks for itself. After all, it will be centered around everyone’s favorite topic: love. The evening is happening in conjunction with an ICP exhibition of contemporary photographs that also explore intimacy and romance. Who could resist?

The annual clam-eating contest at Peter’s Clam Bar in Island Park, August 13: Much is made of the Coney Island hot-dog-eating contest; in fact, it is very fun to watch on the local news (if watching people eat hot dogs really quickly is your kind of thing). Sophie would like to make the case for an alternative option: the annual clam-eating contest at an Island Park clam shack, which is billed as “the most intense eating contest on Long Island.” One reason it’s better is that if you go to spectate, you get to eat clams, which are superior to hot dogs!

This year’s Perseid meteor shower, August 12 or 13: Our intern Owen Park recently alerted the Review’s staff to a very important ongoing event: a massive downpour of shooting stars, perhaps even as many as fifty to seventy-five per hour. (This, according to the American Meteor Society.) The meteor shower actually began in late July but will peak on August 12 or 13, weekend evenings prime for shooting-star-watching. Park notes that this is a “bona fide cosmic event that has no prerequisites, in terms of money or onlineness,” and that, unlike a movie or a show, “it cannot be rewatched.” We’re getting lucky this year, as a low-lit moon means that visibility will be especially high, according to space.com.

Also recommended by editors and friends of the Review for this week: Daniel Lind-Ramos’s El Viejo Griot—Una historia de todos nosotros at MoMA PS1, through September 4 (Alejandra Quintana Arocho, intern); We Buy Gold: SEVEN. at Nicola Vassell Gallery through August 11 (Na Kim, art director); Maureen Dougherty: Borrowed Time at Cheim & Read through September 16 (Na Kim, art director); New York Liberty vs. Chicago Sky at Barclays Center on August 11 (Oriana Ullman, assistant editor); “Back to School with Kirsten Dunst” at Metrograph, beginning with Bring It On on August 4 and ending with The Virgin Suicides on August 18 (Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor).

The Restaurant Review, Summer 2023

Flora season at Gem, photograph courtesy of the restaurant.

The dessert landscape in New York is generally defined by extremes—by how far flavors can be taken from their origins. ChikaLicious, the East Village dessert bar that opened in 2003 and is run by the chef Chika Tillman, is good for the opposite reason: its success comes from its dishes’ almost extreme subtlety of taste. I ordered a three-course menu centered around the bar’s star dish, the Fromage Blanc Island Cheesecake, a kind of cheesecake mousse that’s served (ascetically) in the form of a mound, on a bed of ice, atop a pile of white dishes. It was preceded by an ice cream appetizer with kiwi syrup, and followed by a plate of small cubes that felt like what eating (delicious) chocolate-flavored air might be like. Unfortunately for the subtlety, every flavor was also mixed with the taste of my own blood, which continually seeped into my mouth due to a post-tooth-extraction wound I’d suffered the day before.

Surprisingly, the best dish wasn’t even a dessert but the Very Soft French Omelet, which had the texture of omu rice without the rice. It came topped with truffle butter, was served with an herb biscuit, and was so good that it made me question why Chika was making desserts at all. Our final dish of the night—which, as with the omelet, we ordered in addition to the three-course cheesecake menu—was a plate of pink peppercorn ice cream that I found disturbing only because of how much it literally tasted like peppercorn.

But the food, bloody or otherwise, didn’t even really matter: the cuteness of the bar ultimately took precedence. The entire space could fit about twenty people comfortably, with most of the seats lining the bar, which doubled as an open kitchen. Chika Tillman, a kind of silent spectacle, prepared every dish herself there, while wearing a signature bonnet that she’d had specially made from the pattern of a baby’s hat, while her bow-tied husband (a former jazz musician) served the food on an assortment of heavily patterned china (he let me come to the storage space in the back to handpick my teacup). During the hours I sat at the bar, multiple regulars came to check in with Chika, among them a former sous-chef from Bar Masa who insisted, graciously, that I take a picture of his dessert (something served in a tiny Crockpot). If it wasn’t for my deep-seated fear of intimacy, I imagined, half-delirious from the wound in my mouth, that I would like to become one of them someday—a regular.

—Patrick McGraw

Cafe Spaghetti is my favorite restaurant in New York. There is not really any competition. I started going last summer, shortly after it opened, because I liked the name. There is something delightfully kindergartenish to me about it, a sort of childlike simplicity. I liked telling people, “Meet me at Cafe Spaghetti!” Who could get tired of saying that? (Maybe you. Not me; I’m always saying that.) The ambiance sort of matches the name: there are posters on the wall that range from extremely fun (Louis Armstrong eating spaghetti) to outright tacky (a fake license plate that says Italy). There is a large backyard—previously tented, now walled in glass, open in the summertime—with a blue Vespa in the center. There is a funny little faux shrine to the Virgin Mary or to the pasta gods. As it turns out, the food at Cafe Spaghetti is actually quite good. It helps that my favorite food is pasta, but this is really, really good pasta: cavatelli drizzled with balsamic, spicy crab linguine, a delicious Bolognese topped with a huge glob of ricotta that I ate all winter long. Because, indeed, I kept going back, again and again, until I became that wonderful thing, a regular, greeted by name and occasionally given free glasses of amaro or ricotta toast with pistachios on top.

I tried to write a whole long thing about all the different times and circumstances under which I have been to Cafe Spaghetti—with friends to celebrate, with friends to commiserate, on a date, as an apology dinner, for a birthday, for another birthday, on Sunday nights alone to fight off the blues. This description turned out not to be very interesting, because my Cafe Spaghetti evenings are at their core mundane. Most of the times I have been to Cafe Spaghetti, it has been more or less the same; I go, in fact, because it is generally the same, even as I am myself different, or in different states of being me. I am alarmed by minor changes to the menu. In fact, I feel a sense of quasi ownership so keen that I was annoyed when Pete Wells put the rice balls in his list of New York’s top seven new dishes last year, revealing my little secret, but I couldn’t be that annoyed, because I was also very proud of my friends at Cafe Spaghetti. I once got so irritated that my not-boyfriend went to Cafe Spaghetti without me that he became no longer my not-boyfriend. (There were a lot of other, better reasons, too, but you have to understand that this was a provocation.) The joy of being a regular is of course in the constant comfort of the familiar, but also in integrating an institution into the texture of my life. We’ll always have Cafe Spaghetti, I think, in the Humphrey Bogart voice of my mind, though of course we will not, because I have mourned enough restaurants and bars in my life to understand this is a fiction. But then again, that’s the point of the line—whether it’s there or not, we’ll always have Cafe Spaghetti!

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

Gem is a lovely restaurant run by someone who has been referred to as the “Justin Bieber of food”: the chef Flynn McGarry, who was nineteen years old at the time of its opening. This comparison to Justin Bieber is inappropriate; Gem isn’t really for the masses—though it does face a popular park where I often hang out at night, surrounded by rats. Gem offers a different kind of nature: bare branches and bouquets of snapdragons have been arranged tastefully around a handful of honey-colored wood tables; plates rest on a wreath of young goldenrod inside a wicker basket; there are rough, gleaming boulders in the bathroom sink and Aēsop products above it. At Gem this summer, the menu has been dubbed “Flora Season”: light and wet, mostly green, changing weekly to match the available local vegetables and the microseasons that produce them. The particular week in June I dined there, wildfire smoke was hanging everywhere in New York. Gem’s woven window shades were drawn against the light, which happened to have the color and denseness of Aēsop hand cream though the opposite effect. So when we were presented with a white, fluffy, ice-cold hand towel suffused with what turned out to be bergamot oil (Aēsop, I imagine), I tried breathing through it, to moisturize my airways. My mouth felt like flowers and snow at once: a strange sensation involving only taste and temperature, like eating without the food. Aēsop products, I realized, feel luxurious because they evoke the embalming fluids used on the corpses of pharaohs.

What followed were eight light courses presented over two and a half hours, long enough to make it feel like you are eating almost nothing and in slow motion. The vocabulary that attends a menu like Gem’s is always satisfyingly industrial: there are “compressions” and “reductions,” exotically laboratorial procedures applied to familiar foods and flavors. There was an almost-liquid cheese, like salty cream Jell-O, topped with tiny purple flowers and bright green peas that burst in your mouth like third-wave boba. There was a cold, pond-like soup in which floated ricotta dumplings wrapped in marigold leaves. There was a sorbet with the sharp flavor of a fresh-cut lawn (sorrel). Like the prefatory hand towel, everything seemed to be finished with droplets or spirals of some kind of oil (marigold infusion, pine extraction, anise hyssop essence) that was usually the key to the dish but was perceptible only as a slight shimmer on the surface of both plate and palate. This place was very expensive.

There is always something morbid about the delicately contrived “nature” of art nouveau, and Gem’s aesthetic is a kind of 2020s rendition of it. The contrast between the environmental drama out of doors and the organic whimsy within didn’t strike me as ironic; actually, the apocalyptic atmosphere paired well with food, which gave the impression of having been foraged and prepared by tattooed fairies for some future society in which food is scarce, and strange, but also perfect. I’ve always liked playing pretend, especially “end of the world”—when I was little, I used to practice throwing knives in my backyard, like in The Hunger Games. In the amber light from Canada, what could otherwise have been cottagecore felt cutting-edge, Blade Runner. One imagined supply chains breaking down and elites being forced, finally, to refrain from rib eye in favor of “flower tacos” (one of that week’s desserts: six macerated wild berries wrapped in a pink petal). I think I could get used to eating bugs, if I could breathe in an anise hyssop essence before and after. The restaurant will close its Forsyth Street location on August 26, after five years there—but McGarry promises future projects in the works.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

August 3, 2023

Wax and Gold and Gold

GHADA AMER, PETER’S LADIES, 2007, ACRYLIC, EMBROIDERY, AND GEL MEDIUM ON CANVAS, 36 x 42″. From Women by Women, a portfolio edited by Charlotte Strick in issue no. 199, winter 2011.

During a school break over the long rainy season, when I was fifteen, my father and I took a trip to Addis Ababa. On our way home, the bus stopped in Bedele, a town known for a popular beer of the same name, for a lunch break. We had an hour before the bus departed again, and I asked him to eat quickly because I wanted us to go for a walk near a row of hotels (brothels) a few minutes away from the restaurant. “Remember the prostitute I was ministering to?” I said. “She’s at one of those hotels now.”

I wanted him to help me find Elsa, a woman who used to work at a hotel across the street from our house. Like most of the women there, she was a waitress by day and a sex worker by night. The hotel belonged to a woman who also happened to own one of three TVs in my hometown. While it was a taboo for girls and women—unless one was an out-of-town professional—to go to the hotel itself, we were allowed to visit the lounge next door, where the TV was kept, to watch a game of soccer or a popular Sunday-afternoon program on national TV. The sex workers came over to the lounge occasionally to serve beverages. Several months before my father and I found ourselves in Bedele, I caught Elsa while leaving one of those events and invited her to our home to tell her about Jesus. She accepted my invitation.

Elsa must have been older than me by at least a decade, but she sat across the table shyly playing with her fingers, telling me the story of why she had left her family’s home. I poured the bottle of Fanta she brought me into two glasses and added water to make it last. Before she left, I gifted her my Bible, a precious possession I had obtained through correspondence with an organization in Jerusalem. It was a successful meeting, I thought, and we had kindled what was sure to be a lasting friendship.

She disappeared one morning not long after.

There were always comings and goings at the hotels; the women moved on after a few months in town. But I had expected Elsa to say goodbye and promise to write. I asked one of the boys who worked at the hotel what had happened to her, and he said she’d gone to Bedele.

“I want to follow up on her spiritual life,” I said to my father. “To see if she’s reading her Bible and praying.”

My father agreed to help me look for her. We finished lunch and went to the row of hotels. I was too embarrassed to go door-to-door asking if Elsa was there. It would have been suspicious, too: Why were a seemingly respectable father and daughter looking for a prostitute? Perhaps they are Elsa’s family, looking to apprehend her. Many of the sex workers were runaways who had fallen out with their families or were fed up with village life. (My sister and I were once served tea at a hotel in Bedele by a distant cousin who pretended not to know us. We pretended, too, in the interest of letting her keep her dignity, but also because we did not know what to say.) If my father and I had gone around asking for Elsa, no one would have told us where she was.

We walked in front of the hotels silently. I looked through each door, hoping to spot Elsa walk across the lobby carrying steamy cups of tea on a tray or sitting on some man’s lap. I would have run in immediately, to greet her and shame her into giving me a phone number or a mailing address. It would have been a futile exercise because, had she wanted to share her contact information, she would have done so when she moved.

But I had learned from the street boys I used to hang out with in front of our house that, through persistence, it was possible to make women respond to you. Normally, a girl of my age and stature would have had nothing to do with the street boys who sat outside all day heckling women. But I was allowed to talk to them for the purposes of telling them about Jesus Christ, who made it possible for me to enjoy the company of forbidden people. The boys were dismissive of my proselytizing—“Why would you give us this Good News for free?”—but when the Muslims of my hometown once undertook an unusual conversion campaign, offering each new convert 150 birr, many of the street boys accepted the offer. We remained friends, and they were my primary source on the goings-on inside the few hotels in my hometown.

Elsa was nowhere to be seen, though. The hope of ever seeing her again was fast receding.

“I’ll just pray for her,” I said to my father, who walked beside me silently.

There were two stories unfolding simultaneously. There was the Wax, the story of the lost lamb that I had more or less invented for my father because it was the only way he would allow me, and help me, to look for Elsa. Then there was the Gold, the story of my longing for a friendship with Elsa, a friendship independent of Jesus Christ—simply, a desire for her company.

***

Wax and Gold, or Sem-ena-Werk in Amharic, is an Ethiopian poetic form that has been used for centuries to deliver hidden messages (Gold)—secrets, criticisms of power, insults, vulgar humor, and more—by packing them inside the apparent message (Wax). The Ethiopian philosopher Messay Kebede calls it “the crowning achievement of erudition in the traditional society.”

In high school, we were taught how to locate the hibre-qal—the word or phrase that is hiding the Gold—before digging to uncover the real message of the poem. It was exciting to identify the hibre-qal and suddenly realize that a couplet that seemed to be about piles and piles of fish lying in the wilderness is actually a jab at a promiscuous woman.

Like every good thing, Wax and Gold has its dark sides. In the ultracommunal society in which I was raised, surveilling one another and disciplining our neighbors’ children were part of life, so we looked for privacy in pretention and for self-expression in double-talk. This meant that, in everyday communication, almost anything might be perceived as a kind of Wax and Gold. Sometimes an innocent compliment would seem suspicious because of the person giving it or the way it was expressed. And if I felt paranoid about something kind someone had said to me, I found myself vaguely thinking: Wax and Gold.

Long after my high school years, after I had moved to the U.S., I began thinking about those two layers and how they also reinforce a kind of binary thinking—everything being sorted into Wax and Gold. When I made up the story of the sex worker who needed saving, I was aware of only one layer of Gold that I was trying to hide from my father. It didn’t occur to me until a decade later that it was possible to hide more than one secret.

***

My father and I went back to the bus empty-handed. For the rest of the trip—about eighty kilometers—I kept replaying in my head the afternoon Elsa had come to our house, an afternoon made possible mainly by our particular Protestant brand of Jesus Christ. I say “mainly” because I cannot imagine even most other Protestants in my hometown, including the preachers, going near a prostitute. Even though our Jesus did open the door to a world in which one could befriend prostitutes and street boys and remain free of blame, it took some daring to walk through that door.

A preacher visiting our church from Addis Ababa a few years earlier had spoken tenderly about the time he had ministered to a prostitute: he hugged her, he said, caressed her, played with her hair, and told her about being born again. He told it like a success story, encouraging the rest of us to be as bold in our ministry. Even as a teen, I knew enough to regard that man as a liar with ulterior motives. But I did not think that I wanted to have sex with Elsa, because: how could I? Neither of us had a penis.

I was certain that I wanted to touch Elsa’s face more than anything else, that I wanted to hold her tightly, and perhaps share a bed with her. But that desire couldn’t have been sexual, because some of my closest friends and I sometimes kissed each other’s faces and necks until we were hot and red, and some of us slept together holding each other tightly, with legs intertwined. The border between friendship and romance was not so rigid where I grew up. I remember thinking once during a sleepover with one of my closest friends in high school that sleeping as if we were one body was not enough, that I wished there were a way for me to enter her. And that if I entered her that night somehow, it still would not have been sex. These things were common features of intense friendships, the sort that many people I knew, including adults, enjoyed.

When I couldn’t find Elsa that day in Bedele, I was deeply hurt. I felt that her sudden departure from my hometown had something to do with me. A few days after we hung out at my house, I went to the TV lounge next to the hotel where she worked, a spring in my step. I leaned over the low wall separating the two properties and asked for her. It was dusk, the music in the hotel bar was louder than in the daytime, and patrons were beginning to trickle in. Elsa came out wearing big hoop earrings. “What are you doing here?” she asked, with a look of concern, which broke my heart a little. There was no TV program being shown next door, so I told her that I just wanted to say hello. I don’t remember the rest of our conversation. It was the last time I ever saw her.

A few months before she came to my house, Elsa had seen me shouting across the street at a family friend who sat on the veranda of the hotel reading a newspaper. I wanted to tell him that I had dibs on the newspaper after he was done with it. Elsa said later that she became curious about me that day, thinking it odd for a teenage girl to be so desperate for a newspaper. She asked some of her patrons—men who knew my family—about me, and they told her I was smart. So one afternoon, on my way back from school, she smiled and waved at me, and I began paying attention to her. She was not the most popular employee at that establishment: there was another woman who charged everyone four times the going rate and whom many young men broke the bank to sleep with. I began watching Elsa more intently and making excuses to get closer to that hotel, visiting the TV lounge as often as possible. I noticed that she had a certain melancholy about her, and I decided it was me who was going to make her feel better.

On the bus with my father, I was anxious about alarming him with my own melancholy, so I told myself that I must think of something reassuring to say, perhaps something about the need to save all those prostitutes for Jesus. I ended up telling him Elsa’s story instead—what she told me about why she ran away from home in Addis Ababa and chose this life.

Her parents were upset when she fell in love with a Sudanese man—he was too dark-skinned for their taste. They forbade her from seeing him, and she lost contact with him soon after. Then she found out from a neighbor that she was adopted. She was devastated, both at the news and at her parents’ decision to keep it from her. The resentment over this discovery increased all other resentments, especially the one over the loss of her Sudanese boyfriend. She felt that her parents forced her breakup not because they had her best interests at heart but because they wanted to own her forever. She left and never looked back.

“What’s wrong with a Sudanese boyfriend?” said my father. “As long as he is a good man.”

That made me smile. But I knew my father’s tolerance had its limits. Even my tolerance had its limits, although I did not know this at the time.

About a decade later, in my mid-twenties and living in America, I came to terms with the real real story, the second layer of Gold that was hiding from even me: that I had wanted more from Elsa than what I had with many of my close friends. I wanted to kiss her entire body, not just her face. I wanted to get inside her by any means necessary, not as a temporary game, but as part of an attempt to merge with her, so that I didn’t have to be sick with longing when she wasn’t around.

I place part of the blame for my obliviousness on my Amharic teachers. The emphasis on Wax and Gold, a binary, created the idea that there could be only one layer of Wax scaffolding, one layer of Gold, and a sense that that single layer of Gold is the only and most important truth. If other layers of Gold existed, they would have to be of lower quality—so why were they even important?

Loving Elsa was an important layer for me, and thinking about her still warms my heart twenty-three years after our brief encounter. I have never known a better cure for my apathy than loving someone else.

Mihret Sibhat was born and raised in a small town in western Ethiopia before moving to California when she was seventeen. A graduate of the University of Minnesota’s M.F.A. program, her debut novel, The History of a Difficult Child, was published this year.

July 31, 2023

115 Degrees, Las Vegas Strip

Photograph by Meg Bernhard.

It was 115 degrees outside when I left my house, around 5 P.M. My steering wheel was hot to the touch. So hot, in fact, that I had to steer with the bottom of my palms; some people store gloves in their car during the summer, but I keep forgetting. This was the second Friday of Las Vegas’s heat wave, our seventh consecutive day over 110 degrees. The National Weather Service had issued an excessive heat warning: “Dangerously hot afternoons with little overnight relief expected.” Emergency room doctors treated heat illness patients. At the airport, several passengers and crew members fainted after a plane sat without air conditioning on the tarmac for hours. A man was found dead on the sidewalk outside a homeless shelter.

I drove a few minutes downtown to a Deuce bus stop near Fremont Street, and when I parked I saw a woman in a one-piece swimsuit and tube socks posing for photos in a square of shade. My bus pulled up, and I climbed to the second level. We cruised south, down Las Vegas Boulevard, past wedding chapels and personal injury attorney billboards. The Deuce is my favorite way of traveling to the Strip.

At the Treasure Island stop, two women, their faces pink and perspiring, slid into the seats behind me. “I couldn’t stand there for much longer,” the first woman said.

“That woman doesn’t have any shoes on,” the other said. I looked out the window. A tourist had taken her tennis shoes off and was sitting barefoot at the bus stop. I learned on the news recently that the city’s burn centers had seen an influx of patients with pavement burns, often second- and third-degree.

“There’s a bra,” the first woman snickered, pointing to a blue garment lying in the middle of the street. At the faux Trevi Fountain in front of Caesars Palace, a couple stood on top of the ledge, posing for photos.

“Watch them fall in.”

“It’d probably feel good.”

People crowded every inch of shade at bus stops and awnings. A homeless man sprawled out on a strip of grass. A cardboard sign read HOT, HUNGRY. Bachelorette parties moved in packs, most members clutching plastic cups full of beer, or those giant tubes containing boozy slush. Another time I was on the Deuce, a woman on board claimed her slush tube contained fifty shots. She was very drunk, so no one challenged her.

I wanted to know what would compel someone to visit this city during what could be the worst heat wave of its history. I suppose I too wanted to get out of my air-conditioned house. Now that I was outside for the first time in days, I was surprised at how many people were walking down the Strip. I guess people simply like to go on vacation during the summer, especially Europeans, and many of the accents I was hearing did seem to be German, French, Spanish, and British. Likely many of them had been planning these trips for months. They probably didn’t think that extreme heat—unlike a snowstorm or a hurricane—was a dire enough climate event to warrant cancellation. Maybe experiencing history was part of the appeal. I’d read that some tourists were visiting Death Valley, which holds the title of hottest place on Earth, just in case it broke temperature records that week.

“Endurance tourists,” a friend texted me.

I got off the bus at the Bellagio. Two bellhops, clad in black long-sleeved shirts and pants, loaded bags into a cart.

“We do get the hottest part of the day,” said one bellhop to the other.

“But at least we have the shade.”

Inside the Bellagio’s botanical garden, a giant poodle wearing small boots to protect its paws against the hot pavement stood next to a display of fragrant flowers. I took a surreptitious photo. Then I remembered that a photographer friend’s face had been logged in a casino’s registry after she tried reporting a story inside. I put my phone away and drifted onto the casino floor, where the AC was blasting. Five men in Hawaiian shirts were crowding around a roulette table. The dealer turned to one of them and asked what bet he’d like to place next.

“Whatever you want, we don’t know,” the man said.

“We’re fucking idiots,” another chimed in.

“This is debauchery,” said a third.

The dealer spun the roulette wheel. The men urged the wheel to land on red. Presumably, it did, because they erupted into cheers. In my Notes app, I wrote, “claps and hand shakes and one guy slaps another’s breast. Manhood.” Manhood was an autocorrection, but I can’t remember for what.

Outside, at the Bellagio fountain, a thunderous sound erupted. Arcs of water sashayed through the air as onlookers took videos of the show. According to the Bellagio’s website, the resort sources the fountain’s water from wells, not from Lake Mead or the Colorado River, which are in drought. Twelve million of the fountain’s twenty-two million gallons of water evaporate each year.

Elsewhere on the Strip, machines sprayed pedestrian walkways with mist. Air conditioning poured out from restaurants. In the shade I almost forgot I was in the Mojave Desert.

A man with a cardboard sign reading GOD BLESS US looked parched, so I gave him my water bottle. Now I was out, so I went to the Cosmo’s Starbucks and asked if I could grab a cup of tap water, and by grab I meant can I have one for free. The barista told me that, after tax, the water cup came out to $1.08. I wouldn’t be there long, I reasoned, so I left without water.

The temperature had dropped to 114. A Jesus guy held a sign and yelled, “Vegas wants your money. God wants your soul.” Two showgirls wearing booty shorts and feathered wings took a photo with a teenager and asked how he’d like to pay. A man standing next to him forked over a twenty-dollar bill. “You owe me for that,” said the man, presumably the teenager’s father, as they walked away. Two other showgirls dressed in sexy cop outfits fanned themselves in the LINQ Promenade. “Some girls choose to work in the direct sun,” one of them, a Vegas local, told me. “Those girls are fucking brave.” A couple walked by, and a showgirl leaned over. The man’s face warped with surprise. “Did she just pinch my butt?” he muttered to his partner. At the Flamingo’s live flamingo exhibit, a woman whispered to a gaggle of ducks, “You’re just as fabulous as them.”

At the Deuce stop near the Flamingo, some fifteen people had already gathered. They were all together, on some sort of family trip, and were headed to Fremont Street for the night. From them, I overheard that a bus had just left, but that the next should come soon.

We waited. We sweated. We stepped off the curb to peer down Las Vegas Boulevard, willing the bus to arrive. More people gathered. A couple from the Netherlands. A man in a chef’s coat. The heat was making us cranky. Couples bickered. The chef cursed into his phone. A half hour passed, then forty-five minutes. Things were starting to feel desperate. Finally, I decided to ask the question that was nagging at me. “Why did you come here? In this heat?” I asked the first group. A middle-aged woman with square glasses grinned. “We’re Canadians,” she said, as if this explained things. “We’re crazy.”

Meg Bernhard’s essays and reportage have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. Her book Wine, with Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series, was published this year.

July 27, 2023

Meow!

Photograph by Jules Slutsky.

The other night, the performance artist Kembra Pfahler told me some top-drawer East Village Elizabeth Taylor lore: the dame crossed paths with the about-town character Dee Finley outside a needle exchange one afternoon and later paid for Finley to get an entire new set of teeth. A quick Google search when I got home revealed that the story, as reported by Michael Musto for the Village Voice, was not apocryphal: Finley recalls Taylor arriving by limo at the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, circa 1997—“She had just had brain surgery. Her hair was short and blonde. Liz at her dykiest. YUM!” Taylor, who funded a lot of community work related to the AIDS crisis and had donated to the needle exchange, was apparently out and about that Thursday taking a tour to see what her dollars were doing, and also giving away bottles of her best-selling perfume White Diamonds; though Sophia Loren did it first, Taylor’s powdery Diamonds was what really made celebrity fragrances a thing. (Finley says he promptly flipped his freebie for a couple bags of junk.)

The poet and perfumer Marissa Zappas owns a pair of size thirty-eight brown leather kitten heels that once belonged to Taylor, who died in 2011. When I asked her if they smelled, she said, “Not really, vaguely of green peppers at first.” For Zappas, who’s carved out a niche for herself as an independent perfumer designing fragrances for book rollouts and art installations, as well as olfactory homages to historic figures like an eighteenth-century pirate, Taylor has been a lifelong obsession. She even used photos of her idol as visual aids to help her memorize smells when she was training to become a perfumer. Now, after establishing herself through collaborations with pros and internet-famous astrologers, Zappas has returned to Taylor as the inspiration for her latest scent, Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! Typical for Zappas, whose fragrances are more grown and nuanced than her millennial girlie #PerfumeTok fans might let on, Maggie starts off unassuming, with a warm floral musk as paradigmatically perfume-y as Grandma’s after-bath splash (it smells a bit like Jean Nate, to be specific—a summery drugstore staple since 1935). But then it develops into something more feral, a little loamy: like the inside of an empty can of Coke on a hot summer day, or freshly baked bread with a hint of wet limestone, maybe even an overripe peach traced with rot. As I lay around with my laptop in bed in the afternoon, the fragrance mixes with my sweat, its champagne and violets becoming nutty with a note as sharp as paint thinner.

The first ingredient in Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! is anisic aldehyde, a synthetic scent engineered to resemble anise seed. In its chemical structure, anisic aldehyde is somewhere between a compound that smells like vanilla and one approaching the scent of licorice. As Luca Turin explains in The Secret of Scent, modern perfumery was born in labs about a century ago, when synthetics produced to smell like lemons or roses began to replace natural extracts in fragrances. But aldehydes aren’t just one-to-one approximations of organic smells: “To understand what aldehydes do to perfumes, imagine painting a watercolor on Scotchlite, the stuff cyclists wear to be seen in car headlights,” Turin says. “Floral colors turn strikingly transparent on this strange background, at one opaque and luminous.” Aldehydes are incandescent, like Elizabeth Taylor, a delicate flower animated by something stranger, more wild.

“Complexity is hard to define and easy to recognize,” Turin writes of perfumes. Taylor’s performance in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is instantly recognizable as that: frustrated and smoldering, yet defiantly vulnerable. The new perfume takes its name from one of her lines— “Maggie the cat is alive! I’m alive!”—spoken while pushing her avoidant husband (played by Paul Newman) to forget his recently deceased best friend and fuck her, God dammit. Maggie is desperate for his touch, Taylor convinces us with her leer, at least as much as she wants a baby to lock down his inheritance. One of the reasons we like the woman is that she’s candid about her maneuvers. She doesn’t feign any kind of moral high ground. And while she’s hardened in her determination, she’s soft enough, through Taylor’s piercing portrayal, not to hide how her husband’s neglect stings. A woman self-possessed but not uncorrupted, surrounded by all the fetid decay of a Mississippi plantation during a heat wave, willing to flirt a bit with her father-in-law, she’s a perfect Southern Gothic figure to be interpreted through perfume. Taylor playing her only makes it more fitting: Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! captures the stewing desire of a sex symbol unsexed.

Taylor would also steal those famous lines for her own life: in March 1958, right as production on Cat was starting, her third husband, Mike Todd, died in a plane crash. Wrecked, the actress stayed in bed for a month, but eventually returned to work. Before the film hit theaters, she was coupled up already with her late husband’s best friend, Eddie Fisher. Scandal ensued. A week before the movie’s release, Taylor defended her relationship on the front page of the Los Angeles Times: “Well, Mike is dead and I’m alive. What do you expect me to do? Sleep alone?” Cats are never concerned with pleasing people the way dogs are.

They say it takes four to six hours for a scent to dry down. In its final phase, Zappas’s ode to Taylor is quietly flushed, its soapy sunshine transmuted into sandalwood and skin. Maybe it’s ironic that it’s at my butchest that I’ve come to appreciate the very feline sensibility of being unapologetic—after all, girls: cats, boys: dogs. Zappas’s perfume found me at a turning point when I was becoming suspicious of sacrifice. And so I drench my collarbones and wrists, pairing the potion with Dickies and a fitted, feeling as much a cat as Maggie, notes of ambrette and orris root steel me against being beholden to anyone. Meow.

Whitney Mallett is the founding editor of The Whitney Review of New Writing and the coeditor of Barbie Dreamhouse: An Architectural Survey. She lives in New York.

August 1–7: What We’re Doing Next Week

. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 3.0.

Soon it will be August in New York City, a period when everyone is theoretically out of town—they’re always saying this, anyway, in books like August by Judith Rossner. This is mostly a fiction, that everyone’s at their country house and everything is shutting down, but it’s sort of fun to imagine; who doesn’t secretly enjoy having fun while others are away? For the month of August, the Review is trying a little experiment—highlighting some things that are going on during this supposedly quiet month. Every week, we’ll be compiling roundups of cultural events and miscellany that the Review’s staff and friends are excited about around town. (And maybe, occasionally, out of town.) We can promise only that these lists will be uncomprehensive, totally random, and fun.

F. W. Murnau’s Faust, introduced by Mary Gaitskill at Light Industry, August 1: Gaitskill, who was interviewed for the Spring issue of the Review, will be introducing this 1926 silent film, which, like many flops, is now a cult classic. Gaitskill saw a clip of the film online years before she had read Goethe’s novel, though she knew the basic outlines of the story of the scholar who made a pact with the devil. “That was enough for me to understand and to feel, to believe, the reality of the segment: the flailing despair, the futile vanity, the experience of running through a live, tactile murk of demons and uncomprehending humans, moving slo-mo through their own fates, trying to undo something that can’t be undone,” she told Light Industry.

Heji Shin’s “The Big Nudes” at 52 Walker, open all August: “The Big Nudes” is the photographer Heji Shin’s first solo exhibition in New York since the 2020 show “Big Cocks.” The cocks in question, by the way, were a series of roosters photographed in shocking detail. “The Big Nudes,” meanwhile, will include photographs of pigs posed to evoke fashion models. This show comes recommended by our contributing editor Matthew Higgs, who says, “This relatively rare gallery presentation promises to be something of a midsummer event.” It opened recently and will be up through October 7.

“Live Jerry Garcia Band Set Lists” by the Garcia Project at Brooklyn Bowl, August 5: Recommended by friend of the Review and occasional Review softball first baseman Adam Wilson, this will be an attempt to faithfully re-create actual set lists played by the Jerry Garcia Band between 1976 and 1995. If you never had a chance to see Jerry’s soulful side project live, this is probably the closest you will ever come to it, and real Deadheads will tell you—at great length, if you’d like—that JGB is actually, sometimes, even better than the Dead.

New York City Estate Auction at Auctions at Showplace, preview beginning July 26, auction on August 6: A Jasper Johns lithograph? An Edwardian platinum diamond necklace? An unspeakably tacky oil painting of a blue butterfly? All listed for prices so low they’re unbelievable, which is true, because they’re likely to climb exponentially over the course of the auction. (Or will they?) There’s really nothing like an auction for a dose of randomness, serendipity, and pure gambling thrill; this one collects objects from private estates all over New York City. At the very least, it’s worth a stop by the preview showing, just in case …

Bargemusic: Complete Beethoven Violin and Piano Sonatas on the East River, August 5: An idea from site contributor Elena Saavedra Buckley that is third-date-worthy: go see music at the barge-turned-floating-concert-hall moored in Brooklyn Bridge Park and then go to Sunny’s, the best summer bar in Brooklyn, where there is also likely to be music on a Saturday night. Be on guard, however, if you are seasick or faint of heart, warns the Bargemusic website: “Please be aware that although we are permanently moored, the Barge is in navigable waters and sways with the movement of the East River.”

, Manhattan Beach, August 6: This is, of course, in Manhattan Beach, but for those who happen to be in Los Angeles, our engagement editor Cami Jacobson’s dad will be playing in this legendary annual tournament. Manhattan Beach is apparently “the home of beach volleyball”; this annual tournament is apparently a mix of Very Serious players and people in pink trucker hats who are there for a good time. Jacobson describes the vibe as “very crowded, everyone you have ever met is there, like your whole high school class.”

Triple feature: The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, and The Godfather Coda at Metrograph, August 6: Very rarely can you watch all three Godfather films in one place in a single day. Perhaps not that many people have ever even done this, anywhere. But on a Sunday in early August, Metrograph is showing all three, with a merciful break between parts two and three for dinner. Our web editor, Sophie Haigney, will be there, hiding from the heat.

Also recommended by editors and friends of the Review for this week: Free admission at the Noguchi Museum on August 4 (Lori Dorr); free Indigo de Souza concert in Prospect Park on August 4 (Amanda Gersten and Alejandra Quintana Arocho); Patrick Carroll’s show “Commonplacing” at Bill Cournoyer through August 5 (Spencer Quong); stop by “Visual Volumes: Contemporary Explorations in Book Arts,” all month at the Center for Book Arts (Alejandra Quintana Arocho); Mingus Big Band will be playing two sets every Monday in August at The Dom (Lexy Benaim); fireworks at the Coney Island boardwalk every Friday of August (Lori Dorr); Carly Rae Jepsen on the roof at Pier 17 on August 7 (Amanda Gersten).

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers