The Paris Review's Blog, page 55

May 19, 2023

Shadow Canons: Danzy Senna and Andrew Martin Recommend

Snow on snow in Geneva, Switzerland, courtesy of jenny downing, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Over the last few years, I’ve been reading unappreciated and erased novels by Black artists from the twentieth century. They’ve helped me think about the idea of illegibility—about what the literary world has historically deemed too wild, complex, radical, experimental, or challenging to be included in the precarious and burgeoning Black canon. I’m also interested in why some promising writers give up after only one or two books. What conditions are required to be a writer over a lifetime? Some of these forgotten novels have since been rediscovered, like Nella Larsen’s twenties classics and Fran Ross’s 1974 Black feminist picaresque, Oreo. Others are still fairly unknown, like William Melvin Kelly’s dem and Willard Savoy’s Alien Land, his only novel, published in 1949, about mixed-race identity and passing. My most recent addition to this “shadow” canon is Alison Mills Newman’s Francisco. Originally published by Ishmael Reed’s press in 1974, it’s a California road-trip story about a Black woman artist, musician, and actress whose husband, the eponymous Francisco, is a Black indie filmmaker. Reading it, I can see how it rubs against that era’s prescribed notions of uplift, chastity, and even Black feminism in its celebration of Black love, sensuality, and joy. It doesn’t deal in the familiar tropes of trauma or alienation, and the female narrator is enthralled by her male lover at a time when narratives about Black men as absent or as abusers were more palatable to the mainstream. Thanks to New Directions, who reissued the book a couple weeks ago, it’s found its way back into the world in time for the author herself to experience its discovery.

—Danzy Senna

Read Danzy Senna on Robert Plunket here.

The career of the filmmaker/playwright/novelist/actor Bill Gunn serves as both a cautionary tale about the racial and aesthetic narrow-mindedness of the American film industry and a still-visible signal flare to artists interested in pushing beyond conventional forms. His best known work, Ganja & Hess, which he wrote and directed, is a Black vampire movie with hints of Cassavetes and Jodorowsky, a rough-hewn, hallucinatory freak-out that lodges itself deep in your subconscious. It’s now considered a classic, but even with his increased recognition in recent years, being a devoted Gunnian requires a good deal of digging. His great soap-opera homage/parody Personal Problems, a collaboration with Ishmael Reed and a murderer’s row of excellent Black actors and musicians shot on early video equipment, is now in wide and official circulation. But his first film, Stop!, finished in 1970 but never released by Warner Brothers, requires luck and persistence to see. Having finally tracked it down this month in a fuzzy but perfectly watchable dub online, I can say it’s worth the effort. An improbable anticipation of The Shining blended with the free-flowing sexual gamesmanship of Nicolas Roeg’s then-contemporary Performance, Stop! would have been only the second released Hollywood film by a Black director, and surely the strangest for a long time to come. In its startling mix of genres and frank, often sinister sex scenes, it belongs in a dim, curious video store aisle of the mind.

Gunn’s 1981 novel, Rhinestone Sharecropping, which seems to be as deeply out of print as a book can be, miraculously became available to check out in the Brooklyn Public Library system a couple of weeks ago, after a hold request so interminable and ambiguous that I had begun to doubt the book even existed. But it does! Much of it is a roman à clef following a Gunn-like character’s experience working on a script for a famous football player’s biopic—a clear stand-in for Gunn’s ill-fated real-life work on The Greatest, a Muhammad Ali movie (starring Muhammad Ali!) for which Gunn was denied writing credit. The novel delivers blistering epigrammatic truths about how Hollywood treats artists, and Black artists in particular. “Fear is the gin we are weaned on,” he writes. “Our talent is sustained on a steady diet of terror, even in death. We have visions of being turned out of the graveyard if the order is given and the check is stopped. It is with us in our dreams.” At one point, one racist producer asks another, “What kind of white star you gonna get for a Black movie? … Lassie?” prompting the unforgettable response: “Is Lassie white?!” It seems like the WGA strike would be a great time to scoop this thing up (@McNally Editions? @NYRB?) and unleash it on the public.

—Andrew Martin

Read Andrew Martin on opera here.

May 18, 2023

Rear Window, Los Feliz

Photograph by Claudia Ross.

A sign on the dried grass in front of my apartment building named it the Isles of Charm, a label that suggested—correctly—the irony of the complex’s eventual decay. I moved in on a COVID-era deal, meaning I could afford a studio unit in Los Feliz, though only the kind with communal laundry machines that smelled like Tide pods and urine. The walls were thin, and that was how I met my neighbors.

I shared a hallway and one tiled wall with Brian and Luciana. Brian and Luciana kept their door open all the time, to let the wind in. The distance between their lives and mine was a door screen and the stuttering hum of my air conditioner. I heard everything. They were older than I was, in their mid-thirties or forties. It wasn’t sex, though their arguments occasionally seemed to have an erotic fervor.

“I never loved you,” he would scream.

“You’re a garden-variety narcissist,” she would yell back.

They made up quickly. The morning after a catastrophic meltdown, Luciana would reappear, bouncing down the stairs with their neatly trimmed terriers in tow. They both had matching bumper stickers on their Volkswagens that read WHO RESCUED WHO? with a paw print next to the text. He worked freelance in movies and bought nice leather sneakers. She drank green juice and spoke lisping Barcelona Spanish on the phone. They captivated me. I didn’t understand them at all.

There wasn’t much else going on. It was 2020 and I worked admin for an artist just south of Los Angeles proper. At the office I made batches of bad, overly strong coffee. I coordinated shipping, also badly. Everything was always held up at customs, which felt telling, an international referendum on my abilities. When the boxes arrived at their destinations, I was envious. I imagined myself inside cardboard, headed to Paris or Shanghai.

It was a good job—regular bonuses, champagne at Christmas—but my boredom felt existential. My neighbors were more compelling. At night I came home and lay on the vinyl floor of my studio, my feet touching my fridge, my ear at the doorjamb. Then I waited for Brian and Luciana to start fighting, and they did, like clockwork.

Over time, their arguments grew repetitive. There were more versions of the phrase “I wish I had never met you” than I thought possible. It was a sign, I assumed, of an imminent breakup. It couldn’t go on like this. Soon Brian would move out, and I would buy HBO, or whatever, to entertain myself after work. I would finish that short story. Outside my window, in spring, I would watch the jacarandas bloom.

Instead my landlord cut the jacarandas down. One March night I lay on the floor and heard a door open—their door. Luciana told Brian that it was over. This wasn’t anything new.

“I’m done,” she said.

“I need you,” Brian said.

I heard the two phrases repeat once, and then again, word for word, inflection for inflection. This was abnormal: an exact playback of their conversation. Finally another voice came, interrupting the exchange. The voice was deeper than Brian’s. I briefly contemplated the idea that they had a third—that they were a throuple, a polycule. An exciting twist in the plot. The other man spoke again, more clearly.

“Cut,” he said.

Curious, I staged a trip down the hallway, pretending to check my mailbox. Through their screen door, I saw them: two enormous desktop computers. On each of them was the same frozen, paused image of Brian and Luciana, both crying. Below the images were editing timelines, filled with clips and audio files. Brian clicked play. All the real, raw confessions of feeling I thought I’d heard—they were just bad dialogue.

I took a couple more walks by Brian and Luciana’s apartment in the next months, confirming what I already knew. The demise of their relationship, the one I’d witnessed—or thought I’d witnessed—was actually the rough cut of the movie they were making together. Eventually I saw part of the credits, peeking through their screen, which listed Brian and Luciana as codirectors-writers-actors-producers. Their fights weren’t evidence of suffering. They were a part of what everyone in Los Feliz had but me: “a feature.”

Listening to them lost its Rear Window thrill. I learned instead about the surprising number of home soundproofing options on Amazon. None of them worked very well. I duct-taped foam to the wall above my stove and asked Brian, politely and then not so politely, to shut their door. I finished the short story. I still don’t know what the movie was called or if it even came out, but I don’t need to see it; I already know what happens.

Claudia Ross is a writer from Los Angeles. Her fiction and criticism have appeared in The Baffler, ArtReview, Joyland, Forever, and others. She is working on a novel about archives, television, and gynecology.

May 17, 2023

At Chloë’s Closet Sale

The line outside the Sale of the Century. Photograph by Sara Bosworth.

In the high noon heat of the big hot sun, the intersection of Broadway and Lafayette was an ouroboros. A snake eating its own tail, a snake that was not a snake at all but actually a line of mostly women—who were nearly all young and definitely all well dressed—waiting to go inside a NoHo loft to go shopping. But okay—this was not some sort of run-of-the-mill sample sale. No one waiting in that line was there just because they were looking for a little something to do on a Sunday morning in May. These girls were in line because inside that loft was a woman named Chloë Sevigny. She was there because she was selling her clothes. These girls were waiting in line because the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was Chloë’s stuff, at an event quite literally advertised, in the promotional materials, as the Sale of the Century.

It is not that insane to wait in that ouroboros of a line for three hours, when you think about it. She’s Chloë: Harmony Korine’s muse, wearing bleached eyebrows in the movie Gummo. Dancing to the O’Jays’ “Love Train” in a subway car in Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco. Appearing naked and pregnant on the cover of Playgirl. She’s the kind of celebrity who can get her one million Instagram followers to wake up early on a Sunday to buy her toothpaste. The second the sale began, it was already a viral event—like Black Friday for fashion-school freaks. TikTok, Twitter, and Instagram were flooded with vibey haul videos, memes implying sartorially motivated violence, posts about new female friendships forged in line, allusions to the Bush presidency, and suggestions that maybe you could find a girl to date among the racks? And most importantly: a reminder that “if you’re in line for Chloë Sevigny’s storage-unit sale, please stay in line.” It is true that a specific subset of New Yorkers seemed to be saying (or posting), “chloë sale! chloë sale! chloë sale!”

To be clear, I am one of these girls, a lover of Chloë, someone who has spent years showing the stylist at the hair salon a picture of her in Kids. But I did not have to stand in the ouroboros of girls, for a few important reasons. The first is that Chloë wasn’t the only person selling clothes in NoHo that afternoon. The Sale of the Century was actually put together by Liana Satenstein, a former Vogue staffer who organizes closet clean-outs for fashion icons. In addition to Chloë’s stuff, the sale also featured selections from the closets of Sally Singer, the former creative director of Vogue who now heads fashion at Amazon; Lynn Yaeger, a Vogue contributing editor known to wear whimsical Comme des Garçons frocks; and the longtime Paper magazine editor Mickey Boardman. I was Sally’s assistant at Vogue when I first moved to New York, once upon a time. Therefore, when I arrived at 676 Broadway at 11:55 A.M., I sent her a text and floated to the front of the line with my friends Anika and Sage. The other reason we got to skip the line is because it was my twenty-seventh birthday, and sometimes when you turn a new age you get lucky.

At the sale, in the loft, were, predictably, racks upon racks of clothing, some of the items costing hundreds of dollars, or hovering around a thousand. Still, some of it was very reasonable for good-quality designer vintage. A wall of antique Victorian blouses with high-necked, intricate embroidery, more or less all under a hundred dollars. A literal chess set from Chanel, priced to sell at $450. A gray Brooks Brothers suit with shorts instead of pants. A reddish-pink ballerina skirt with a Blumarine vibe. A scarf commemorating the nuptials of one Prince Charles and Princess Diana. Prada purses and a pair of Birkenstocks. A lot of it looked like normal vintage clothing—it was better curated, but the items more or less achieved their mystique because of their former owners.

And the people: it was not as crowded inside as you would expect, but it was still crowded. And the media: an army of photographers from every fashion magazine in New York, asking the shoppers their age, their job, how to spell their names. Blasting from the speakers was electronic, compressed, sugary music that made me feel like I was in a movie about going to a Chloë Sevigny closet sale. A girl with drawn-on eyebrows was wielding a vintage camcorder, walking around and interviewing shoppers. A mother with blue hair and her twenty-something daughter told me they had gotten in line at 9:30 in the morning. I heard a rumor that a few girls got in line at 6 A.M., and it doesn’t really matter if the rumor is true. There were club kids in platform sneakers and fashion gays in polo ties; girls with shaved heads in tattered slip dresses and girls who dressed like little orphans from a sketch by the hand of Ludwig Bemelmans. Anika got photographed by W magazine and gracefully changed in front of the photographer into the new outfit she had just purchased—the Brooks Brothers suit and a baby-doll blouse—like some kind of movie star. At one point I accidentally began to talk to a reporter from the New York Times, answering his questions—(my name: Sophie; my age: twenty-seven, as of three hours ago; what I was doing here: shopping for various items)—before he abruptly stopped when he realized I too was a writer.

And Chloë was there with her son, a beautiful little three-year-old boy with a halo of blonde curls. Mostly she sat on a couch by the back entrance to the loft, but she wandered into the dressing area too. In fact, she walked past me as I was trying on this bizarrely baroque white linen horseback riding suit. It seemed reasonably priced at eighty-five dollars, fit me perfectly, and made me look like a tragically beautiful stable boy in a Watteau painting. “Looks great,” she said as she watched me check myself out in the mirror. “I wore that to dinner with Nicolas.” (She meant Ghesquière, the legendary former creative director of Balenciaga). Obviously I bought the suit. What would you have done if you were in my situation? Sage and a nineteen-year-old twink in Marie Antoinette makeup were told by one of the reporters that they should get married because, in Sage’s words: “We didn’t beat each other up over what was best described as a Union soldier cosplay crop top.”

I walked around and observed, pretending I was a feudal lord of a different époque and that all the shoppers, these girls and gays in their opulent little outfits, were my beautiful serfs. I said hello to Sally and locked eyes with Tommy Dorfman. I saw on social media later that day that Chelsea Manning had been there too—the Daily Mail had written about it, calling her a “35-year old security consultant.” I leafed through Lynn Yaeger’s rack of Comme des Garçons skirts and briefly considered buying a see-through purple Gucci blouse from Sally. I ended up making two important purchases, both from Chloë’s rack: the baroque horseback-riding thing and this gorgeous sleeveless Victorian blouse with a high neck, priced at sixty-five dollars. Then I was shepherded outside by a crowd-control person who gently suggested leaving now that I had completed my shopping.

The line was still incredibly long—only forty-five minutes had passed. A frantic British woman in hangover sunglasses came up to me and asked if I thought there would still be clothing if she got in line now. I said probably not. What I wanted to say was: Save yourself babe, it is really crazy in there.

We left, and Anika and I walked into the Village. I stepped inside of a café bathroom to change into my new riding suit thing and splash cold water on my face. The buzz of my morning caffeine had dulled and I now felt exhausted leaving the Sale of the Century. I got on the F train to go to Red Hook and when it went above ground at Smith and Ninth Street suddenly it was summer and the music in my headphones was Prefab Sprout and New York looked like a big fantasy snow globe that you could buy at a gas station somewhere very far away. As it turned out Ihad stayed up until 5 A.M. the night before and slept with my ex-boyfriend; I texted him a procedural question about what had happened and he said that twenty-seven was going to be the best year of my life. And how could it not be? I had my new clothes. I was living in Chloë’s New York.

Sophie Frances Kemp is a writer in Brooklyn, originally from Schenectady, New York. She has published non-fiction in GQ, Vogue, and The Nation, and fiction in The Baffler and Forever. She has a forthcoming novel called Paradise Logic.

May 16, 2023

Primrose for X

London buses moving. Licensed under CCO 2.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

William Blake once wrote to a friend that he conversed with the Spiritual Sun on Primrose Hill. Today his words saying as much are carved on the stone curb atop the grassy knoll where the Druid Order has gathered for the Autumn Equinox since the poet’s times, and today still do. For the Druids, the primrose wards off evil and holds the keys to heaven (in German the cowslip primrose is appropriately called Himmelschlüsselchen). For herbalists it is a sedative, pain reliever, and salve. It keeps depression at bay. The primrose is the flower of youth, love, lust and sweetness, rebirth and poetry. Eating one can manifest fairies. In Albion it is among the first blooms of spring. The “rathe Primrose” is the opening flower Milton notes to strew upon the “laureate hearse” of Lycidas.

“Primrose for X” opens with Fanny Howe “tracking Blake on Primrose Hill” and twelve quatrains later ends with her on a high-speed train that “raced away from London / and Blake’s theophanies.” What she finds in the lyric interim are no golden pillars of Jerusalem or celebrity sets. No St. Paul’s Cathedral, Shard, or Wharf highlight the skyline as they do for visitors in relief on the metal panoramic sign at 66.7 meters high. Here the “unsteady skyline” is “like a graph that measures / markets, snails and heartbeats”—one of many instances in Fanny Howe’s poetry of her in-dwelling similization of the world around us, as if these comparative truths always existed as air to breathe. Meanings break free with snails and “shucked” at the end of the line that contrasts the brain with the “slippery” heart that also slips across the stanza. And how the vital heart monitor beats with the little line’s cadence “How am I still here / at every thump?”—the question posed to herself or Thou of her own life’s longevity answered by the steady pulse of spirit-touched heart, along with doubt’s silence.

“Every word must come from my acts direct,” Howe writes of poetry’s impossible task in “Philophany,” an earlier poem in her most recent collection, Love and I. “Primrose for X” comes toward the end of the book before two final poetic sequences. The placement of individual poem-to-poem sequences through the whole takes on the shape of neumatic notation, rhythm pitched to love’s life. Here lines move within snail-paced thought, the measure of attention where, as Buber describes it, “love comes to pass.” Here lines move in a spark with the restless “I,” who finds the X subjects of love’s gift among the poor immigrant women in Victoria, impoverished children, “drugged and dirty and crushed” boys of Kentish Town, and the victims of a father’s violence, half-allegorized by a machete. Catherine Sophia Boucher Blake belongs here, too, in the hidden vision—she who learned the secrets and practice of her husband’s illuminations and signed the Parish Register as bride with an “X.”

Blake loved quatrains as much as the fourteen-syllable line. “Primrose for X” is only one of three poems in Love and I written in consistent quatrains, and the longest of the three. Its symmetry doesn’t follow any set metrical or syllabic pattern like the iambic tetrameter of Blake’s “London.” Instead each quatrain’s short line-to-line syllabic variation counters the overall symmetry, unsteady rhythm bound to beating image and thought and the needs of the heart. Only one stanza is composed entirely of trimetric lines, in the alien description of the “boys hunched,” as if to heighten the nightmarish fairy-tale quality of “What is created by humans / is almost always alien.”

The phantoms of the last stanza emerge out of the violent “grievous years” as the poet speeds away in the darkness toward the unseen Channel and the children of The First Church. Phantoms or theophanies. The ninth-century Irish theologian and poet John Scotus Eriugena defined the latter in his Periphyseon as “divine radiance,” “self-manifestation of God,” “traces of the Truth,” “clouds of heaven,” “brightness,” “divine manifestations … which take their names from the eternal causes of which they are the images.” Man-made causes—“machete or his father’s hand”—or eternal causes. That “every visible and invisible creature can be called a theophany, that is, a divine apparition.” These are the indecipherable forms of love Howe’s words track and bring into impossible light—her poetry philophanies.

—Jeffrey Yang

I was tracking Blake on Primrose Hill

one damp summer night.

Bundles of white chestnut flared

under the streetlights.

London’s unsteady skyline

was not a reassuring one

but like a graph that measures

markets, snails and heartbeats.

When one brain was weary

one heart was not.

The brain can be shucked

when all the air is gone but the heart

is slippery and needs a touch of

spirit to nourish it.

How am I still here

at every thump?

The heart has its needs

and feelings sewn like threads

into branches and seasons

that we pencil as trees.

The Irish women with brass-capped hair

and tight mouths

and a Muslim woman with five girls and one boy

are all sadly clad at Victoria.

In poverty some screaming brats

are fat, and some are starved

into silence on their father’s laps.

No father might be worse than that.

What is created by humans

is almost always alien.

The hissing buses and trains

in Kentish Town, boys hunched

in bunches on the lock

drugged and dirty and crushed

their eyes like lizards veiled

and blind in retreat while

a man with a machete

cut a fellow down, blood

all over his hands. Proud

of being a killing kind of man.

Machete or his father’s hand: which one

caused this crime?

The aughts were grievous years

for boys and men.

Crowds of phantoms covered

Kent’s fields as the Eurostar

raced away from London

and Blake’s theophanies.

Fanny Howe is the author of more than twenty books of poetry and prose. She grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and studied at Stanford University.

Jeffrey Yang is the author of the poetry collections Line and Light; Hey, Marfa; Vanishing-Line; and An Aquarium.

A shorter version of Yang’s piece on Fanny Howe’s “Primrose for X” will appear in the forthcoming anthology Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, which will be published in January 2024 by Graywolf Press. “Primrose for X” is reprinted from Love and I with permission of Graywolf Press.

May 15, 2023

The Dress Diary of Mrs. Anne Sykes

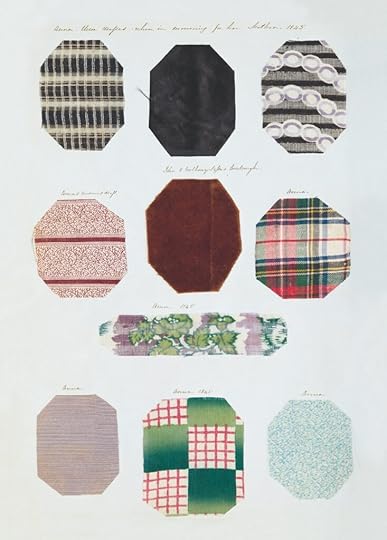

“Anna. Three dresses when in mourning for her mother. 1845.” Photograph by Kate Strasdin.

In January 2016 I was given an extraordinary gift. Underneath brown paper that had softened with age and molded to the shape of the object within, I discovered a treasure almost two centuries old that revealed the life of one woman and her broader network of family and friends. It was a book, a ledger of sorts, covered in a bright magenta silk that was frayed along the edge so that a glimpse of its marbled cover was just visible. The shape of the book had distorted—it was narrow at the spine but expanded at the right edge to accommodate the contents, reminding me of my mum’s old recipe book, which had swelled over the years as newspaper cuttings and handwritten notes were added.

This book, measuring some twelve and a half inches long by eight and a half inches across, contained pale blue pages, which were unlined and unmarked. As I carefully opened the front cover and looked at the first page, my breath caught: this was indeed a marvel. Carefully pasted in place were four pieces of fabric, three of them framed in decorative waxed borders—these were scraps of silk important enough to have been memorialized. Accompanying each piece of cloth was a small handwritten note inked in neat copperplate, including a name and a date: 1838.

As I turned more leaves, a kaleidoscope of color and variety unfolded. There were small textile swatches—sometimes only two pieces at a time, and sometimes up to twelve—cut into neat rectangles or octagons and pasted in rows that blossomed across each page. The notes were written above each snippet of fabric, sometimes curving around the shape of it. I knew from the outset that this was something precious, an ephemeral piece of a life lived long ago. It was a beautiful mystery.

The elderly lady who gave me the book explained to me what she knew of its provenance, which was very little. While she was working in the London theater world in the sixties, a young man assisting her in the wardrobe department found this unusual curiosity on a market stall in Camden. He thought that the pages of the scrapbook, filled as they were with colorful textiles, might be of interest to the wardrobes of the theaters where she worked. The book remained in this lady’s possession for fifty years until she passed it on to me.

There was no immediate indication of who might have created this amazing dress diary, as I called it—of who had spent so much time carefully arranging the pieces of wool, silk, cotton, and lace into a document of lives in cloth. While there was much I was uncertain of, however, one thing I knew for sure from the careful handwriting that arched over each piece of cloth: this was the work of one woman. I just didn’t know who she was.

In the months that followed, I began to try and unravel some of the stories that might be contained in the album’s pages. Rather than detail its contents digitally, I had a sense that, to be authentic, I needed to write everything down in longhand. I bought a leather-bound book of handmade paper and a black ink pen and started at the beginning, transcribing each tiny caption. I wrote down names, dates, fabrics, colors, and patterns, trying to see who might emerge, looking out for clues about who the author could have been. I counted more than two thousand pieces of fabric: some patterned, others plain; some large and others much smaller. There were pieces paired with longer captions, and others that bore simply a year or nothing at all.

The book was full of names: Fanny Taylor, Hannah Wrigley, Mary Fletcher, Charlotte Dugdale, Bridgetanne Peacock, Maria Balestier. I recorded more than a hundred different names in the book, binding them to clothes worn long ago. Some appeared with great frequency across its pages and others only fleetingly, acquaintances made and lost among friendships of longer standing.

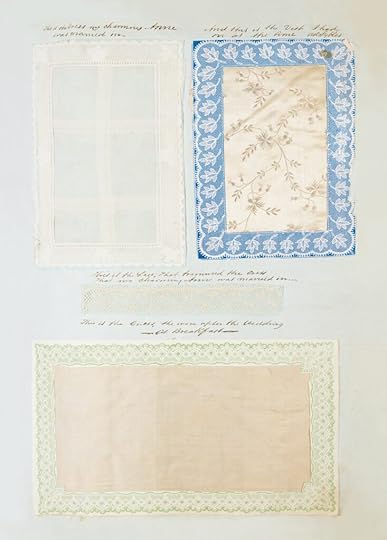

“The dresses worn at Miss Wrigley’s dance. January 1845.” Photograph by Kate Strasdin.

Only seventy fragments were associated with male garments, and only seventeen of the names recorded were those of men. It seemed that at a time when so much of literature and the arts was focused on the endeavors of men, this was a book dedicated to the world of women. I decided to try to piece together the lives of some of these women through the clues that were left behind, scant though they often were. Using what felt like a forensic approach in its detail, I focused on fragments of cloth to illuminate the world these women inhabited, enabling a wider context to emerge. What began to appear were the tales of an era, placing these lives into the industrial maelstrom of the nineteenth century, with all its noise, color, and innovation.

The structure of the album, the names, and the cloths themselves all suggested that this was not a volume compiled in the rarefied spaces of the aristocracy but something more quotidian: the creator being a woman of some means, but inhabiting the world of the well-to-do middle classes. This woman and others—women whose lives would otherwise go unrecorded, hidden in the shadows of history—found themselves unwittingly front and center in this story.

The practice of making collections of one kind or another was a common activity in the nineteenth century. Taxonomies of the natural world, like cataloguing flora and fauna, abounded. Plant hunters were collecting seeds, entomologists were charting insect life, and in the 1830s—the decade in which this diary commenced—Charles Darwin was beginning to pose his theories outlining evolutionary changes that were to shake the very foundations of scientific understanding. The determination to bring order in a shifting world reached into domestic spaces too, and households around the UK began to create albums of ephemera. Early photographers produced fantastical albums with prints and watercolors, and scrapbooks were filled with keepsakes, autographs, poems, and drawings.

Women’s creative pursuits were many and varied, but rarely were their efforts recognized as anything more than diversions. The decorative handicrafts of women have traditionally been read as acts of leisure: idling away the hours in the domestic spaces afforded to the middle and upper classes, and wasting time on inconsequential endeavors. More recent revisionist histories have begun to challenge these perceptions and to take more seriously the objects made by women—to view them as artistic practices rather than foolish accomplishments. Take Mary Delaney’s botanical collages. At the age of seventy-two, Delaney, whose colorful life up to that point had included friendships with Jonathan Swift, George Frideric Handel, and the great social commentator of the day, William Hogarth, embarked on a project that would become her legacy. She watched one day as a geranium petal fell to the floor and felt compelled to replicate the fragile petal in paper, carefully cutting out its replica. She repeated the process until she had created a life-size collage of the plant, which she called a “flower mosaick.” She then arranged the cutouts onto a piece of black paper and pasted them on. So lifelike was the result that her friend the Duchess of Portland proclaimed that she could not tell the real flower from the paper one.

While the creator of the book I was examining used a pale blue background for her own form of mosaic, Mary Delaney created the inkiest of black backdrops by painting white paper with black watercolor until it was as dark as it could be. She practiced her art form over the next decade, cutting thousands upon thousands of tiny slivers of paper in all the colors of the botanical rainbow to create hundreds of her now-famous collages. “I have invented a new way of imitating flowers,” she wrote in a letter in 1772. So detailed were her creations that botanists still refer to their accuracy, and they are studied with awe at their home in the British Museum.

“The first dress I wore in Singapore.” Photograph by Kate Strasdin.

The dress diary in my possession is rare, but it is not the only one of its kind to remain. One famous surviving example was created by Miss Barbara Johnson, starting in the middle of the eighteenth century and continuing into the early nineteenth century. As a single woman whose finances had to be carefully managed, Johnson began to catalogue the textiles that she purchased to make into clothing. She snipped pieces of precious cloth and pinned them into a large accounting ledger, including details of their type, their cost per yard, and the kind of garments that they would become once sent to the dressmaker. She even pasted in small black-and-white engravings from early fashion publications to indicate the ambitions that she had for her new clothes. For more than seventy years she maintained her album, adding 121 samples to its pages. It served a practical purpose, helping her to balance her books and providing financial clarity. More than that, though, it was a colorful record of Johnson’s journey through life and of the central place that dress played in her day-to-day world. The album was saved by her extended family and eventually became part of the collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, one of their rare treasures. It is the only one of its kind in their collection.

In fact, in the whole of the UK, I failed to find another album like either Barbara Johnson’s or the one that had fallen into my own hands. That is not to say they do not exist, or were not created in greater numbers in decades past. My mystery diarist could not have been the only one in the nineteenth century to choose to record an aspect of her life in this way, and the very tactility of cloth lends itself to this form of remembrance. There may well be volumes of fabric scraps languishing in trunks in attics, or wrapped in the bottom drawer of an elderly chest. There may even be examples that were once catalogued and then forgotten in an archive or a museum, their value yet to be identified.

A dress diary suffers from the double ignominy of being about largely female experiences and about dress—concerns that, in the nineteenth century at least, lent them little by way of artistic merit. The field of dress history has been an academic discipline that has had to fight for recognition amongst more traditionally respected scholarship, the study of clothing being perceived as an ephemeral concern. There have been many occasions during my own career when I have been introduced at an academic conference as a historian studying (cue a long pause and a raised eyebrow) fashion. The slight bemusement that has so often accompanied such introductions reveals a deep-seated perception of dress as superficial and inconsequential—that to be interested in clothing is to lack seriousness. Yet here we all are dressed in clothes, making daily decisions about how we will face the world. We might use dress as our armor, a protective carapace to shield us from censure, or we might use it to express our place and space. Even if we have no interest in fashion, we still choose garments that are indicative in some way of the cultural landscape that shapes each one of us. The creator of my album shared these daily decisions, preferring this color or that fabric in her own environs.

In America there are a handful of albums that share similarities with mine, volumes created by women describing, in material form, the decisions they made about the contents of their wardrobes. Where the diary in my keeping seems to differ from the few other surviving dress diaries is that it recorded lives beyond the maker’s own, encompassing those in her orbit. This woman decided at some point to gather the contents not only of her own wardrobe but those of her family and friends, and to memorialize them in her bright pink silk-covered album. The decision to refer to herself always in the third person made the identification of the author all the more challenging, and, unlike in more intimate diaries, the captions establish a curious distance. Perhaps the point was to try to archive the fabrics objectively rather than making it a personalized object. It is difficult to establish what her motives were. One caption, inked above a woven silk picture of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, hints at a strategy of collecting. The note reads: “Mr McMicking’s contribution to this book given to him by one of the Gentlemen of the French Embassy to China.” Her note suggests that she was actively sourcing textiles for her book, casting her net far and wide to find interesting additions to its pages. Over tea perhaps, making polite conversation, she may have shown Mr McMicking the book she was compiling and requested that he might add to its pages with a contribution of his choosing.

Finally my careful transcribing of each tiny caption paid off. Across a single square of floral printed cotton, on the top right-hand corner of one of the pages, came the breakthrough I had been hoping for. It was to be the revelation that cracked the code for the entire volume. In the same neat, fine script that populated the whole book were the words “Anne Sykes May 1840. The first dress I wore …” She was revealed. The one and only time that she referred to herself in the first person, Anne Sykes identified herself as the keeper of the book; the creator of its 422 pages; the person who had pasted the 2,134 swatches of fabric into her album and recorded the names of those 104 different people and their clothes. I had found her.

Anne’s identity radiated out in myriad hues and materials, connecting her to her world and allowing us to join her. Discovering that Anne Sykes was the hitherto unknown creator of the book that I had been meticulously transcribing was at once both exciting and perplexing. I felt certain that she had to be a dressmaker, a woman whose role in life was to clothe her clients, taking a keen interest in shape and style, keeping the secrets of bodies. In that moment I could never have anticipated just how much I would be able to uncover.

Swatches in the album revealed that Anne attended parties and fancy balls, her book being full of the formal clothes that both she and her friends wore on these occasions. It was full, too, of the everyday—of cotton and wool, of dressing gowns and slippers, bonnet ribbons, petticoats, and cloaks. Cloth of all types was a valued commodity and its purchase was not undertaken on a whim. She recorded the purchases that she made from Miss Brennand’s smallwares establishment and on shopping trips that her friends made to Liverpool and Manchester. Individually the swatches gave little away, but by piecing together clues, it was possible to weave together the strands of Anne’s life into a colorful patchwork of family and friends.

“This is the dress my charming Anne was married in.” Photograph by Kate Strasdin.

That Anne kept her dress diary more or less chronologically is evident from its structure and the dates recorded. The album starts at the very commencement of Queen Victoria’s reign and maps those momentous decades of everything that came to be Victorian—a parallel life synonymous with industry and empire. Although the notes are brief, the writing changes. As the years pass, the notes become scarcer and the fine copperplate larger and not so neatly formed. All of life is revealed as the pages progress: mourning clothes to mark the loss of loved ones, dresses worn to christenings, gifts for birthdays and Christmases.

In a sense, Anne’s album is a form of life writing—taking in ordinary folk, not the grandees of traditional written histories but the bystanders, the participants in everyday life, their loves and losses, joys and sorrows. It is a fragmentary story of life experienced at home and abroad, in a domestic world and an international one, of courage in unfamiliar lands and of building a community of friends. Through small and seemingly inconsequential wisps of fabric, Anne Sykes’s diary lays bare the whole of human experience in that most intimate of mediums: the clothes that we choose to wear.

Dr. Kate Strasdin is a fashion historian, museum curator and lecturer at Falmouth University, where she teaches the history of fashion design, marketing, and photography.

From The Dress Diary: Secrets from a Victorian Woman’s Wardrobe, out from Pegasus Books this June.

May 12, 2023

Opera Week

Metropolitan Opera House. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 4.0.

In Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, the narrator, Adam, goes to the Prado every morning to stand in front of the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden’s The Descent from the Cross. On one particular morning, another man is standing in his place, looking at the painting, and this man suddenly bursts into tears. Adam is irritated and confused: “I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art and I had trouble believing that anyone had, at least anyone I knew.” I too have worried about this; a painting has never moved me to tears. A poem has never changed my life. This is why the opera came to me as a surprise—both my love of it and the fact that, the first time I saw La Bohème, I cried through the whole fourth act. The pathos! I was deeply moved by the tragic story and by the register of the musical spectacle, but it was something more primal, too. Here was an art form that seemed not to shy from melodrama but move into its absolute depths, and then transcend and transform them.

I love opera not as an expert, or even as an informed connoisseur. I love it as an amateur, a near-total beginner. And despite its reputation, I think opera is surprisingly accessible, in part because of its absolute embrace and elevation of human feeling. I’m sure that as I spend more time in the Family Circle seats at the Met, I will learn more, and I might even become discerning. But for now I am going for pure pleasure.

This week, we’re publishing a series of pieces on opera. Colm Tóibín shares a letter to his mother, written from the moment when he fell in love with opera; Nancy Lemannconsiders the contenders for the greatest Don Giovanni of all time; Andrew Martin recounts a visit to Nixon in China; Adam Kirsch comes to the defense of Faust. Plus, two reviews of recent opera productions, a piece adapted from Patrick Mackie’s Mozart in Motion, a dispatch from our poetry editor, and a behind-the-scenes look at the making of Michael Bazzett’s poem in our Spring issue.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor at The Review.

The Review’s Review: Don Carlo and the Abuse of Power

Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara, El Greco. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Don Carlo is the kind of opera that has gone out of fashion. I cruised through half-empty rows when I saw it last fall, just days after attending a packed-to-vibrating weeknight production of The Hours – , the two-act opera adaptation of a 1998 novel and its 2002 film adaptation – promoted heavily on the subway and. Verdi’s four-hour-long political tragedy, set during the Spanish Inquisition in the sixteenth century, feels more like eating your operatic vegetables. Its place in the canon was actually secured by the Met, whose onetime general manager Rudolf Bing fished it out to open the 1950 season.

Based largely on a historical play by Friedrich Schiller, Don Carlo imagines a backstory to some real events in the life of Carlos, Prince of Asturias, who was briefly engaged to Elisabeth of Valois before she instead married his father, King Philip II of Spain. Schiller invented an anachronistic friend for Carlos: Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa, who distracts the heartsick prince with the political cause of Flemish independence. Meanwhile, Philip, bitter and paranoid over his loveless marriage, contemplates getting rid of his son and his treacherous friend with counsel from the blind and ruthless leader of the Inquisition.

Among the work’s Shakespearean qualities—Anglophone audiences might especially recall Hamlet—is the fact that there are multiple versions of it, in both French and Italian. Verdi revised it several times between 1866 and 1886. The original libretto is in French—Don Carlos—but its five-act runtime tested even nineteenth-century audiences. Verdi then lopped off the entire first act, which shows Carlos and Elisabeth’s coup de foudre in the forest of Fontainebleau. Act 2 of the original, which became Act 1 of the more widely performed Italian translation that I saw, starts soon after Philip’s wedding, when Elisabeth has become the queen of Spain—and Carlos’s stepmother. The Met experimented with the five-act French version last season, but has since backtracked to its repertory standard. Skipping the first act deflates the opera’s romantic plot—turning the love triangle between Carlos, Philip II, and Elisabeth into mere inciting incident—but heightens its political and religious drama.

Eponym aside, Don Carlo is more vessel (for Rodrigo’s ideas) and pawn (in his father’s power games) than protagonist. Crucially, in this drama of Enlightenment values, he appears deeply irrational. He loses his composure within the first act and practically faints onto his stepmother, singing, “I love you, Elisabeth! The world is nothing!” Freeing herself from him, she counters, “Well then! So, wound your father! Come, soiled by his murder, drag your mother to the altar!” Into this void enters Rodrigo, who radiates s Reason and extols liberty, particularly for the downtrodden people of Flanders. “Lend your aid to the oppressed Flanders!” he exclaims. As they pledge their commitment to the cause in a spirited duet, Carlo seems barely conscious that he’s signing on for treachery against his own family.

Both Schiller and Verdi, who was an ardent Italian nationalist, treat Rodrigo, the avatar of their latter-day values, indulgently. Though he ends up being assassinated for his political intrigue, Verdi sends him off with a poignant aria where he sighs, “Io morrò, ma lieto in core”—I die with a happy soul. Rodrigo’s activist zeal must have seemed a little quixotic even in the nineteenth century, after the Revolutions of 1848 were so decisively snuffed out, but he’s newly compelling in our age of liberalism in crisis. At times, Rodrigo seems like the opera’s conscience; at others, like an opportunistic interventionist avant la lettre. When he decries the plight of Flanders, it’s impossible not to think of the contemporary war in Ukraine—whose geopolitical intrigue, soon after my viewing, became linked, strangely enough, to a mysterious cyberattack on the Met—or, on the other hand, of our recent wars of so-called liberation in the Middle East.

I’m getting a little off-topic, but grand opera—the nineteenth-century tradition of historical operas with lavish sets and an epic sweep—is, among other things, a serious invitation to contemplate such matters as state power and history. The cause of Flanders, introduced as randomly to the weak prince as to the audience, doesn’t stay abstract for long. The production unleashes all its powers of spectacle to show the terrifying core of the Inquisition, the auto-da-fé. Amid joyful fanfare—“This happy day is filled with gaiety!” sings the chorus—Flemish Protestants in long pointed caps are led to be burned at the stake. The director, David McVicar, stylizes sixteenth century Valladolid as a cement-gray metropolis, with rows of dystopian arches that recall Mussolini’s Rome. Pity the people who live under such a cruel yoke, and pity them again that their fates will be determined by such weak and shiftless men as Carlo and Philip. What grand opera also does, with its scale (even when lightly abridged) and its mix of the dramatic and the marvelous, is prepare us to confront, with heightened sensibilities, a vision of evil—as opposed to workaday badness, weakness, or fallibility.

Philip’s study, dominated by an outsize Christ on the cross, is the site of the climactic exchange between the aging, paranoid king and the awesome, terrible Grand Inquisitor, who wrestle with the crown’s relationship to the altar. The Inquisitor—played by John Relyea, incarnating one of opera’s great villainous basses—introduces himself through an octave, somewhat reminiscent of the stone guest who comes to punish Don Giovanni. When Philip asks if he must sacrifice his son, whom he fears both as a romantic rival and a delusional political liability, the Inquisitor reminds him, without missing a beat, that “God sacrificed his own son to save us all.”His impregnable authority puts the royals’ petty maneuvers in context: “Everything bows and is silent when faith speaks!”

No one can be a hero when the church and state are such a rock and hard place. Tyrannical institutions box off every character’s choices. It’s not even clear what “duty” means, under these circumstances—what is owed, and to whom. The character who seems best adapted to them is Elisabeth, who recognizes “the emptiness of the vanity of this world.” But her stolid acceptance is not exactly rewarded, because the authority she accommodates and subjects to is rotten, craven, and truly evil. Different people get the last word in different versions of this opera, but in the original, it belongs to the monks of San Yuste, who observe that even a great emperor has become no more than “dust and ashes.”

Krithika Varagur is the author of The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project and an editor of The Drift.

The Review’s Review: Emma Bovary at the Opera

Lucie de Lammermoore. Victor Coindre, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

My first memory of opera is Bugs Bunny or maybe The Pink Panther Show: those Saturday-morning cartoons where the fat lady sings and shatters a glass. Much later I began to date a man who had been to hundreds of opera performances (a fact I found not only shocking but literally unbelievable) and so I went from watching no operas to almost one a month. The one I’ve enjoyed the most by far was the Met’s spring 2022 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, staged in a town in the depressed Rust Belt. I had already read about Lucia: it’s the opera that inspires Emma Bovary to cheat on her husband (again, and more dramatically). And yet I didn’t know anything about its plot, because Flaubert doesn’t describe it; the opera serves merely to connect Emma to her younger self, the pretty country girl who had had bigger dreams than a failure of a husband and a cad of an (ex-)lover. At the opera, Flaubert writes, “d’insaissibles pensées” come over her: “elusive thoughts,” uncapturable thoughts, incomprehensible thoughts. What’s coming over her is fantasy.

Nabokov said about Emma Bovary that she was the quintessential “bad reader,” the one who reads “emotionally, in a shallow juvenile manner, putting herself in this or that female character’s place”: above all, in the place of Lucia di Lammermoor, the tragic sister of a warlord, kept from the man she loves, who slaughters her husband on their wedding night in a crazed delirium and herself dies. But to read Madame Bovary as purely reprobative seems to me cold to the point of insanity; as Flaubert said, of course, “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” We are all fantasists, incomplete and incoherent actors in search of a character, and who can blame or even fail to admire Emma: so moved by art that she too will destroy her life for a fantasy of love, and die.

And yet I myself was not at all moved by the opera to change my life. I could admire the lead soprano Nadine Sierra’s expressiveness, virtuosity, beauty; I could delight in the claustrophobic sets, in the (perhaps a tad excessive) use of projection. But the experience was not at all like that of, say, watching a nineties film and wanting to be a slacker so badly I regretted ever getting a job. Opera, you might say, is an outdated fantasy machine: too mannered, too heroic, too … boring?

On the other hand, I increasingly find it hard to understand what people’s epistemic relationships are to all sorts of things: the massively popular Love Is Blind is an almost mockingly Brechtian, stiff recitation of clichés (“I would call myself, maybe … an empath?” “Me too!”). The people around me who seem the most obviously engaged in absurd, even delusional, fantasies of impossible and irresistible love—the ones who take their cues from Before Sunrise, from the films of Kieślowski—are the ones who feel themselves most assuredly and assertively to be living in truth.

Now, when I see people at the opera, I see people delighted less by the fantasy of opera than by the fantasy of themselves as operagoers. The divide is immediately evident between the regulars, the season-ticket holders, the devotees, in their wheelchairs and sneakers, and those in gowns and tuxedos taking pictures on the plush red stairs. Yet I suppose we all must get our scripts from somewhere. I am not sure what anyone is feeling at the opera, as the slightly repulsively modern chandelier goes up and the lights go down, but I am fairly certain what they would like to be feeling—would like themselves to be capable of feeling.

Ann Manov is a writer living in New York.

Faust and the Risk of Desire

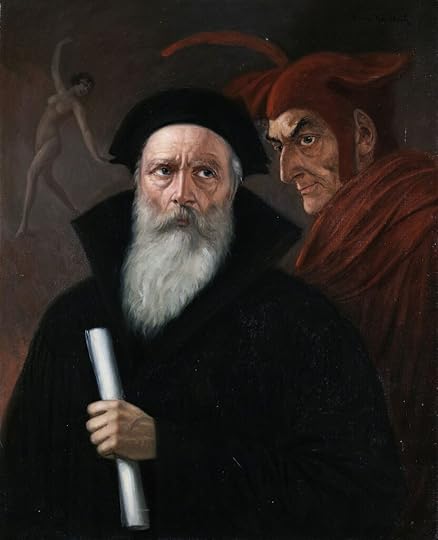

Faust and Mephistopheles. Painting by Anton Kaulbach, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I first discovered opera in 1991, when my tenth-grade English teacher killed a couple of class periods by showing the movie Amadeus. The bits it contained of The Magic Flute and Don Giovanni were seductive enough to send me to the nearest outpost of the Wherehouse, a California record-store chain, where the classical and opera section was an afterthought. When I compare it to the contemporary infinity of Spotify, however, the limited selection now seems a kind of blessing: with so little to choose from, it was impossible to feel overwhelmed.

It was also an advantage not to have anyone telling me which operas were great and which were passé. Not until much later, for instance, would I learn that by the nineties, Gounod’s Faust was already a century past its prime. It debuted in Paris in 1859 and quickly became a worldwide hit, especially in the U.S., where it was chosen to inaugurate the newly founded Metropolitan Opera in 1883. But in time, Faust’s blockbuster status made it a byword for middlebrow entertainment, a bit like The Phantom of the Opera today. When Edith Wharton set the first chapter of The Age of Innocence at a performance of Faust, it was a way of critiquing the provincialism of 1870s New York from the vantage point of 1920. For instance, Wharton pokes fun at the fact that the opera, originally written in French, is sung in Italian, the language Americans were used to hearing in the opera house at the time.

The novel opens with the main characters watching the passionate love duet at the end of act 3, in which Marguerite, a virtuous young woman, is seduced by Faust, a middle-aged scholar who has sold his soul to the devil. As he begs to “caress your beauty,” she plays a game of “he loves me, he loves me not,” picking petals off a flower. It is a sign of Marguerite’s childlike innocence but also of her ambivalence: she has already fallen in love with Faust, but can’t be certain whether he really loves her or is only trying to get her into bed. She uses the game to convince herself that Faust’s love is genuine, and when she plucks the last petal with a triumphant “He loves me!” Faust immediately confirms it: “Yes, believe this flower … He loves you! Do you understand that sublime, sweet word?”

Wharton’s opera scene is the perfect opening to a novel about how old-fashioned people lived lives as passionate as our own, despite or even because of their Victorian constraints. Watching Faust, Newland Archer takes a complacent satisfaction in the idea that the young woman he’s engaged to marry, May Welland, is too innocent to understand the erotic rapture of Gounod’s music. “She doesn’t even guess what it’s all about,” Wharton writes. “And he contemplated her absorbed young face with a thrill of possessorship in which pride in his own masculine initiation was mingled with a tender reverence for her abysmal purity.” But it is this very purity that will lead him to lose interest in May and fall in love with her cousin, the Countess Olenska, whose scandalous past has taught her the meaning of “that sublime, sweet word.”

I didn’t know any of this when I bought a recording of Faust, on two CDs, with Nicolai Gedda as Faust, Joan Sutherland as Marguerite, and Nicolai Ghiaurov as Mephistopheles. When it came to love and seduction, at fifteen I was as inexperienced as May Welland. Still, as I listened and followed along in the libretto, I think I understood what was going on in Gounod’s music. In fact, adolescence may have been the right time to encounter it, since really Faust is about the power of adolescent emotion.

When the devil Mephistopheles appears to Faust in act 1 and says he will grant any wish in exchange for his soul, Faust turns down offers of money, glory, and power. What he wants, he says, is “a treasure that contains them all: I want youth.” Youth means sex, of course—“young mistresses … their caresses and desires”—but it is also a way of being alive, a more enthusiastic sort of participation in life. In the opera’s opening scene, Faust hears men and women on their way to work in the fields at the crack of dawn, content with their lot and praising God, and he despairs because he feels completely detached from them.

The first word he sings in the opera is rien, “nothing,” and he suffers from the kind of nihilism that today we would call depression—the feeling that nothing matters or is worth doing. In asking Mephistopheles for youth, he is really asking the devil to banish this feeling, and to return him to a time of life defined by “the energy of powerful instincts.”

The duet at the end of act 3 marks the point when his wish comes true. After seeing Marguerite from afar, and after she rebuffs his initial advances, Faust is now certain she returns his love. Gounod’s music tells us that reciprocated passion is the most totally involving experience of which human beings are capable. The two voices linger over the word eternelle, showing us that in love, time disappears.

In the same year Faust premiered, Richard Wagner completed the score of his own opera about holy and unholy love, Tristan und Isolde. In their famous duet, Wagner’s lovers also sing that they are ewig, ewig ein, eternally one. In both operas, the rapturous music prefigures, and stands in for, an erotic union that can’t be depicted on stage.

The great difference is that, for Wagner, sex is just as holy as love, of which it is the natural and necessary emblem. His love-music directly imitates the rhythm of sex, building to an unmistakably orgasmic climax. But for Gounod and his librettists Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, who adapted the story from Goethe’s epic poem, sex is a betrayal of love, the triumph of the flesh over the spirit.

Throughout their duet, Marguerite makes clear—verbally and musically—that she wants to have sex as much as Faust does. But she is terrified of the possible consequences—illegitimate pregnancy and social disgrace—which would fall only on her. The sexual dynamics of the scene are complicated: Marguerite is telling Faust that he could get her to agree to sex, but that she hopes he won’t, because she would regret it afterward. “Leave, I tremble, alas! I am afraid! / Don’t break the heart of Marguerite!” she begs. And the duet ends with him agreeing to honor her wishes: the power of her “divine purity,” he says, “triumphs over my will.” He leaves her, promising to return in the morning.

At this moment Mephistophele suddenly appears. Mocking Faust for his failure to get Marguerite into bed—“Professor, you need to be sent back to school,” he jibes—the devil tells him to wait and listen to what she will sing when she thinks she’s alone. What follows is an aria of such unabashed desire—Marguerite sings of “trembling” and “palpitating,” waiting for Faust to return—that he betrays his promise and rushes back to her. As the two fall into bed, we hear the derisive laughter of Mephistopheles. All this talk of eternity is just a way of dressing up our biological urges; if you put a man and woman together, they’ll end up doing the same thing as any pair of animals. The consequences prove to be just as dire as Marguerite feared: she gets pregnant, Faust abandons her, and in the last act we find her in prison for infanticide, having lost her sanity.

Like Violetta and Alfredo in La traviata and Don Giovanni and Donna Elvira in Mozart’s opera, Faust and Marguerite helped me begin to understand things about love and sex that were still remote from my experience. In many ways, of course, these works were products of an alien culture: no one in my world associated sex with sin, as Marguerite does. But for that very reason, opera had more to teach me about the riskiness and perversity of desire than did Madonna and George Michael, who sold transgression on the radio. Thirty years later, I’m still perpetually surprised by the boldness of an art often thought of, by people who don’t listen to it, as old-fashioned.

Adam Kirsch is a poet, critic, and editor. His most recent collection of poems is The Discarded Life, published by Red Hen Press.

May 11, 2023

A Spring Dispatch from the Review’s Poetry Editor

Illustration by Na Kim.

Sometimes, on the campus of the university where I work, a visiting writer will explain to a captive audience how great poems—more often than not his own—get written. These explanations often sound a bit mystical, occasionally even mystifying. So I was amused to read the opening lines of Dobby Gibson’s tongue-in-cheek “Small Craft Talk,” a poem our readers discovered in a box of paper slush, and which you’ll find in our Spring issue:

In some languages the word for dream

is the same as for music

is the kind of thing poets like to say

Before you know it, Gibson’s takedown of writing-program clichés shades into a wonder at how poems can make us feel ourselves, as Wallace Stevens once put it, “more truly and more strange”:

as if you’re hearing the song

of your own mind sung into being

so that you become yourself

by becoming more like another self

When I read a poem like Gibson’s, I usually think, Wow, what a great poem. Then, maybe a little bit enviously, I read it again and try to imagine writing it myself. So it was when I first came across the brutalist intimacies of Tracy Fuad’s “Birth,” or Malachi Black’s poem of cosmic epiphanies “in a burned-out Ford sedan”—both of them also in our Spring issue. How did they do that? I wondered, scratching my head. I felt the same amazement reading Joyce Mansour’s poem, translated by Emilie Moorhouse, which begins “I stole the yellow bird / That lives in the devil’s sex,” and which somehow manages to reach from hell to the heavens in nine lines of verse. Whatever could have possessed this cigar-smoking Egyptian Surrealist to go poking around in the devil’s crotch? Maybe it was a late-night game of exquisite corpse with her friend André Breton that led to her hilariously abbreviated final lines:

As for me, my slumber runs along the rooftops

Mumbling, waving, making violent love,

With cats.

This spring, for readers who’d like to learn more about how poems like these happen, we’ve launched a new online series, Making of a Poem. This week, Michael Bazzett lifts the hood on his portrait of the artist as a (very) young man, “Autobiography of a Poet.” (You might be surprised to learn that when Bazzett hears the poem in his head, it’s spoken by Tony Soprano.) Kyra Wilder, writing about the events that inspired her poem “John Wick Is So Tired,” reveals how that poem very nearly involved a different Hollywood franchise altogether. “I was reading a lot of Ian Fleming that fall,” Wilder writes. “I got pretty obsessed with the fact that he included a recipe for scrambled eggs in a James Bond story … So, it was either going to be ‘John Wick Is So Tired’ or ‘James Bond Could Make You Some Pretty Good Eggs.’”

To accompany the series, we recently published an essay by Matthew Zapruder, “My Royal Quiet Deluxe,” from his forthcoming Story of a Poem: A Memoir, which also illuminates the roundabout, vexing, and yes, occasionally mystical routes that poems take on their way into existence. As a young poet, Zapruder found an old typewriter in his grandparents’ attic and began the hypnotic practice of hammering out whatever poem he was writing over and over again, each version slightly different from the last. “I began not to think about but to hear how necessary each word was or wasn’t: if I skipped something to avoid typing it for the fiftieth or hundredth time, and then when I read it, it sounded fine, I would never look back,” he writes. “I also had a secret, immutable rule. If I ever mistyped a word—horse for house, ward for word, vary for very, or find for fine—I would have to keep it. It was a pact I made with myself, to trust my unconscious, that what seemed to be an error was actually a sign.”

Here’s to oracular typos and scrambled eggs! We hope you’ll keep an eye out for more Making of a Poem pieces on our website, and that you enjoy all the poems—including new work by Nam Le, Uche Nduka, and many others—in our Spring issue.

Srikanth “Chicu” Reddy is the poetry editor of The Paris Review.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers