Richard Conniff's Blog, page 111

February 6, 2011

Flaming Barricades and the Species Seeking Life

You might enjoy a short interview that aired recently, about flaming barricades and other hazards of the species seeking life, on John Hockenberry's PRI show The Takeaway.

The Species Seekers also continues to pick up enthusiastic reviews, with a few excerpts listed below. A friend recently asked if the book includes any sex and, after desperately searching my memory for a bodice-ripping anecdote (other than Mary Kingsley plunging into a pit lined with sharpened stakes), I had to say no. Even so, it's been moving up steadily on sales lists. I'd appreciate your help in spreading the word:

A swashbuckling romp…brilliantly evokes that just-before Darwin era. (BBC Focus )

An enduring story bursting at the seams with intriguing, fantastical and disturbing anecdotes. (New Scientist )

[Conniff's] enthusiasm for his subject and admiration of these explorers is infectious . . . an entertaining survey. (Kirkus Reviews )

An anecdotal romp through the strange history of naturalism. Absurd characters, exciting discoveries, and fierce rivalries abound. (Outside Magazine )

[This] history of the 'great age of discovery' is spellbinding. (Publishers Weekly )

This beautifully written book has the verve of an adventure story. (Wall Street Journal )

Lost and Gone Forever

Here's my latest Specimens column for the New York Times, based on my new book The Species Seekers.

Species die. It has become a catastrophic fact of modern life. On our present course, by E.O. Wilson's estimate, half of all plant and animal species could be extinct by 2100 — that is, within the lifetime of a child born today. Kenya stands to lose its lions within 20 years. India is finishing off its tigers. Deforestation everywhere means that thousands of species too small or obscure to be kept on life support in a zoo simply vanish each year.

So it's startling to discover that the very idea of extinction was unthinkable, even heresy, only a few lifetimes ago. The terrible notion that a piece of God's creation could be swept off the face of the Earth only became a reality on January 21, 1796, and it was a body blow to Western orthodoxy. It required "not only the rejection of some of the fondest beliefs of mankind," paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson once wrote, "but also the development of fundamentally new ways of thinking." The science of extinction was one of the great achievements of the 18th century, he thought, a necessary preamble to Darwinian evolution, and almost as disturbing.

The Great Auk, last seen in 1852.

Specimens from the American colonies played a key part in this revolution. A tooth weighing almost five pounds, with a distinctive knobby biting surface, had turned up along the Hudson River in 1705, and quickly found its way to Lord Cornbury, the eccentricgovernor of New York. (Cornbury was either a pioneer in gubernatorial bad behavior or an early victim of dirty politics. He subsequently lost his job for alleged graft, amid rumors that he liked to dress up as his cousin Queen Anne.) Cornbury sent the tooth to London, where "natural philosophers" began a long debate over whether this "Incognitum," or unknown creature, was a Biblical giant drowned in Noah's flood or some kind of carnivorous monster. Decades later, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington puzzled over similar teeth when they turned up again in the Hudson and Ohio River valleys.

A few of the tens of thousands of species that scientists say have gone extinct or become critically endangered over the past 30 years.

Whatever creature had once gnashed its food with such grinders was evidently now gone, perhaps thankfully. But this disappearance challenged widely held faith in the Great Chain of Being, the idea that the natural world was a perfect progression from the lowliest matter on up, species-by-species, jellyfish to worms, worms to insects, culminating in the Earth's most glorious specimen, Homo sapiens. A corollary of the Great Chain held that God had created all forms that could be created. What might seem like gaps in the Chain were merely missing links that had yet to be discovered. Proposing that some forms had gone extinct, an American writer complained, was "an idea injurious to the Deity."

Jefferson also held out against extinction, though mainly because he liked the idea of big fierce animals as symbols of American greatness. "Such is the economy of Nature," he wrote, "that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken."

It was the French anatomist Georges Cuvier who proved otherwise. When he took the podium at the National Institute of Sciences and Arts in Paris in January 1796, he was just 26, a handsome, confident young man, with thick reddish hair and a strong chin. His new post at the National Museum of Natural History allowed him to compare a range of pachyderm specimens, including African and Asian elephants, the Siberian mammoth, and the Incognitum, which he called "the Ohio animal." Cuvier made side by side comparisons of anatomical structures to sort specimens into separate species (incidentally inventing the science of comparative anatomy). Then he argued persuasively that animals the size of the mammoth and the Incognitum could hardly have escaped notice by "the nomadic peoples that ceaselessly move about the continent in all directions." It's not clear why this argument for extinction was so persuasive. Cuvier is still notorious in some circles for having later rashly declared an end to the era of "discovering new species of large quadrupeds" — only for a parade of such creatures to turn up over the rest of the 19th century. But even Jefferson seems eventually to have been persuaded, at least after Lewis and Clark returned from their expedition to the West with no evidence of a living Incognitum.

Mastodon tooth (Yale Peabody Museum. Photographer Jerry Domian/Yale University)

Cuvier gave the Incognitum its modern name, mastodon. (Those knobby cusps reminded him, oddly, of breasts, so he took mast from the Greek for "breast" or "nipple," and odon from "tooth.") He also went on, through brilliant analysis of newly discovered fossils, to create a catastrophic vision of past worlds in which "living organisms without number" had vanished forever, some "destroyed by deluges," others "left dry when the seabed was suddenly raised … and all they leave in the world is some debris that is hardly recognizable to the naturalist."

This idea of mass extinctions thrilled and terrified the 19th-century imagination. Cuvier was "the great poet of our era," according to the novelist Honoré de Balzac. In cultivating his own legend, Cuvier had popularized the magical idea that by carefully studying a fragment of bone he could resurrect the appearance of an entire extinct animal. Balzac now set out to do the same thing in fiction, building characters on the smallest details of gesture and dress. It was arguably the birth of literary realism. But Cuvier's larger influence was in his apocalyptic vision of vanished worlds, which echoed down ominously through much of the 19th century. In his 1850 poem "In Memoriam," for instance, Tennyson yearned for the comforting assurance of the older world view:

That nothing walks with aimless feet;

That not one life shall be destroy'd,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete …

Instead, every cliff and quarry now reminded him that Nature does not work like that: "She cries, 'A thousand types are gone:/ I care for nothing, all shall go." Extinction wasn't just a threat to the natural world but to us. Tennyson wondered if mankind, Nature's "last work, who seem'd so fair, Such splendid purpose in his eyes" would also end up being "blown about the desert dust,/ Or seal'd within the iron hills?"

It was a good question then, and an even better one now, when we are living through precisely the sort of mass extinction Cuvier only imagined.

February 3, 2011

A Southern Minister Against "Scientific Moonshine"

John Bachman

There are plenty of reasons to admire John Bachman, a minister and naturalist born 180 years ago today. When he wasn't tending his multi-racial flock at St. John's Lutheran in Charleston, South Carolina, he published studies in botany, ornithology, and mammalogy.

Among the many new species he discovered were the Swainson's warbler, Helinaia swainsonii, and Bachman's warbler, Helminthophila bachmani.

He and John James Audubon collaborated on a book, Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, and published detailed descriptions of dozens of mammal species, making taxonomic distinctions of a high standard for the day. The families also collaborated in their personal lives, with two Audubon sons marrying two Bachman daughters.

But I like Bachman most because he also stood up against some of the most dunderheaded and determined racists of his day. It was the primetime for scientific racism–"scientific moonshine," as Frederick Douglass put it–the theory put forward by some white scientists that other human races were actually separate species.

Bachman neatly sliced this argument to shreds, using simple anatomical evidence from Homo sapiens and other species. (You can read more about it in Chapter 12 of The Species Seekers.) In making the case that humans are in fact a single species, he was defending scientific truth and (for once) religion, too.

The most rabid voice of scientific racism in the 1850s was an Alabamba physician named Josiah Nott. His Hippocratic oath did not keep Nott from voicing his wish to "kill of{f} Bachman," to "skin Bachman," to see him "cut up into sausage meat." After what he deemed a particularly effective riposte, he wrote of Bachman, "I really feel as if a viper had been killed in the fair garden of science, and I hope his death will be a warning to all such blasphemies against God's laws"–the laws, that is, that made blacks a separate, inferior species, and keeping them as slaves the work of righteousness.

February 2, 2011

A Revolution in the Ways We Live and Die

One night in 1877, in a squalid port city on the southeastern coast of China, a Scottish doctor named Patrick Manson performed a small experiment that would soon revolutionize the ways we live and die. What was his subject?[image error]

1. A dog.

2. A mosquito.

3. A human being.

4. A laboratory rat.

And the answer is:

Patrick Manson performed a small experiment with mosquitoes. The scope of the test was limited and the design badly flawed. But it was the beginning of a spectacular quarter century in which the work of the species seekers would bear fruit, enabling humans for the first time to control diseases that had plagued them forever. His experiment focused on elephantiasis, a common disorder in the tropics that he suspected was caused by parasitic filarial worms.[image error]

He also hypothesized that the worms were passed from one individual host to another by a blood-sucking insect. Somehow, from examining what was essentially a paste of mashed filarial-infected mosquitoes, Manson also discerned what happened next: Newly liberated from their first host, microfilariae passed through the mosquito's abdominal lining and took up residence in the muscles of its thoracic cavity. There they continued to develop, [image error]"manifestly … on the road to a new human host."

He had discovered "a new and revolutionary concept," according to medical historian Eli Chernin–"that certain bloodsucking arthropods can transmit human disease." It would eventually save millions of lives—arguably, millions every year in the modern era–and immortalize Manson as "the father of modern tropical medicine."

There's a lot more to this story—you can read about it in The Species Seekers.

LA Times on The Species Seekers

Here' s the L.A. Times review of The Species Seekers:

As prehistoric cave drawings attest, humans have been fascinated by other species since earliest times. But it wasn't until the 18th century that a comprehensive, science-based system for identifying and classifying them was developed. For that we can thank Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist and physician, who first devised a pyramid of categories — including kingdom, class, order, genus and species — into which all life forms could fit.

Linnaeus' "Systema Naturae," published in 1735, got many things wrong, but it was still revolutionary. As Richard Conniff writes in "The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth," the "ability to distinguish one species from another and to sort out the relationships among species was … a critical advance for understanding life on earth." It also, he writes, inspired a great age of discovery, in which a new type of naturalist traveled the globe in search of previously unidentified life forms. In the course of collecting and cataloguing plant and animal species, humans "stumbled from the security of a world centered on our species, created for our comfort and salvation, to a world in which we are one of many species."

The 18th century and 19th century naturalists at the center of this highly readable book were often arrogant adventure seekers, desirous of the status that came with putting their names on previously undiscovered species. But even though they were rarely driven by a pure desire to advance science, many of them were intensely interested in getting things right and in understanding how species fit into their ecosystems.

Though Linnaeus fervently believed that God was responsible for the creation of each and every species, his disciples inevitably began to question that notion. Fossils suggested an array of species that no longer existed (although, as Conniff notes, Thomas Jefferson was convinced that mammoths probably still roamed the vast, largely unexplored West). The questions of the 18th century naturalists led to new ways of thinking, and to a rejection of long-held assumptions about the natural world. This in turn led to the 19th century's theory of evolution.

In covering such a vast sweep of natural history, Conniff gives short shrift to many of the individual characters and their exploits. There is frustratingly little, for instance, about Charles Darwin's voyage on the HMS Beagle. But what Conniff does include is well worth reading, including an excellent analysis of the interaction between Alfred Russel Wallace (whom Conniff calls the greatest field biologist of the 19th century) and Darwin in developing a theory of evolution.

Whereas Darwin spent years collecting his thoughts about how species adapted and changed over time in response to their environments, Wallace came to many of the same conclusions in a burst of inspiration. In 1858, collecting specimens in the Spice Islands near Papua New Guinea, Wallace was forced to his bed with a bout of malaria. He spent the time reflecting on what he had observed in the field and, he later wrote, it "suddenly flashed upon me … in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain — that is the fittest would survive."

Wallace quickly sketched out his ideas about how the survival of the fittest over time would cause the extinction of some species at the same time new ones emerged. When finished, he sent his ideas off to Darwin, with whom he had developed a correspondence.

Darwin was deeply shaken on receiving Wallace's treatise. "All my originality," he lamented in a note to a colleague, "whatever it may amount to, will be smashed." Instead, his scientific friends moved swiftly to set up a joint presentation of the two men's ideas before a meeting of London's prestigious Linnean Society. In their introduction, Darwin's colleagues made clear that while the two men had "independently and unknown to one another, conceived the same very ingenious theory," Darwin, they let it be known, was the deeper thinker, the true theoretician who had first come to the ideas and developed them most thoroughly. The 1858 presentation caused surprisingly little stir. As Conniff notes, "The society's president went home muttering about the lack of any 'striking discoveries' that year. And so began the greatest revolution in the history of science."

Conniff's book is filled with rogues and heroes, and their not infrequent overlapping explorations make for entertaining reading. The so-called Long expedition of 1819, the first government-sponsored exploration of the American West to include trained naturalists on the team, began mapping the tributaries of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers before starting overland to the Rockies. Thomas Say, one of America's most skilled zoologists, led the expedition's scientific mission, and it wasn't always easy to convince his companions of the worth of his endeavors. At one point, bringing what he believed to be a new species of deer back to camp, he was forced to sketch it quickly before his hungry fellow explorers butchered it. He had wanted to take it back intact. Still, with his carefully documented field notes and specimens, he "was able to introduce America to some of its most iconic animals, among them, the coyote, the swift fox, the great plains wolf, the lazuli bunting and the orange-crowned larkspur."

Say often found, however, that he had been beaten to the discovery of Western species "by a brilliant crackpot" named Constantine Rafinesque, who was everything Say despised in an amateur naturalist. He was slapdash and had little formal training, but he possessed a zeal for discovering and naming new species, and on more than one occasion Say carefully described what he believed to be something entirely new only to discover that Rafinesque had dashed off a far inferior report of the species previously.

In the end, the anecdotes Conniff tells, though often fragmented, are more effective than the narrative connecting them. Still, the stories are more than enough to make this ambitious book well worth reading.

It's easy to think that the great discoveries have all been made, that the 18th century and 19th century naturalists, by arriving at the party first, got all the goodies. But Conniff dispels that notion. "[E]ven today," he writes, "with the total of known species pushing 2 million, new species continue to turn up almost everywhere, at times much closer than most of us care to contemplate." And with an estimated 50 million more species yet to be discovered, he says, "we still live in the great age of discovery."

// <![CDATA[// // // Copyright © 2011, <a href="http://www.latimes.com/" target="_blank">Los Angeles Times</a></p>

<br /> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/gocomm... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/commen..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/godeli... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/delici..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/goface... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/facebo..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/gotwit... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/twitte..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/gostum... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/stumbl..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/godigg... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/digg/s..." /></a> <a rel="nofollow" href="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/goredd... alt="" border="0" src="http://feeds.wordpress.com/1.0/reddit..." /></a> <img alt="" border="0" src="http://stats.wordpress.com/b.gif?host..." width="1" height="1" />]]>

February 1, 2011

Living on Insects, at Three Pence Apiece

[image error]The passion for natural history has often had an upper class image, for better or worse. Period movies and novels treat it as a country house pursuit, with governesses helping the children net frogs in the reflecting pool and young ladies rearing butterflies in the hothouse. And many celebrated naturalists, including Joseph Banks and Charles Darwin, did in fact come from wealthy backgrounds.

Social connections made it easier to land a suitable post in the foreign service, or on a Naval expedition; money also obviously helped in a field that was never likely to prove useful or remunerative. British naturalist Edward Forbes, who struggled to get by on the dismal wages available to a marine zoologist, once remarked, "People without independence have no business to meddle with science." The anatomist Richard Owen was more adept at currying the favor of the good and great; he got the essayist Thomas Macaulay to pass the hat on his behalf: "The greatest natural philosopher may starve while his countrymen are boasting of his discoveries."

But many naturalist, like the Amazonian explorer Henry Walter Bates, supported themselves as freelancers, by gathering specimens for sale to collectors back home. By good fortune, Bates found a capable specimen dealer named Samuel Stevens to dispose of his duplicates on a commission basis. Stevens, whose shop was on Bedford Street around the corner from the British Museum, expected to sell a typical insect specimen for four pence, with three pence going back to the collector in the field.

With this meager funding, Bates spent eleven happy years of hard work in the Amazon. He headed out into the forest early each morning dressed in boots, trousers, an old hat, and a colored shirt with a pin cushion on the front for keeping six different sizes of insect pins at the ready. He carried a shotgun over his left shoulder, one barrel loaded with No. 10 shot, the other with No. 4, for anything from a small bird to an animal the size of a goose. In his right hand, he carried his butterfly net. A leather bag at his left side held ammunition and a box for insect specimens. A game bag on his right held further supplies, with leather thongs for hanging lizards, snakes, frogs, large birds and other specimens. And having spent a long day in the field, Bates often worked late into the night preserving his new treasures and protecting them from rats, ants, and other scavengers.

For all this effort, his total profit for one stretch of 20 months was ₤27.

Crows as Clever Tool-Makers, Tolerant Parents

Natalie Angier, always a graceful writer, has a nice piece in the New York Times today about the crafty tool-making skills of New Caledonia crows. Here's an excerpt:

Videos of laboratory studies with the crows have gone viral, showing the birds doing things that look practically faked. In one famous example from Oxford University, a female named Betty methodically bends a straight piece of wire against the outside of a plastic cylinder to form the shape of a hook, which she then inserts into the plastic cylinder to extract a handled plug from the bottom as deftly as one might pull a stopper from a drain. Talking-cat videos just don't stand a chance.

So how do the birds get so crafty at crafting? New reports in the journals Animal Behaviour and Learning and Behavior by researchers at the University of Auckland suggest that the formula for crow success may not be terribly different from the nostrums commonly served up to people: Let your offspring have an extended childhood in a stable and loving home; lead by example; offer positive reinforcement; be patient and persistent; indulge even a near-adult offspring by occasionally popping a fresh cockroach into its mouth; and realize that at any moment a goshawk might swoop down and put an end to the entire pedagogical program.

You can read the full article here.

January 31, 2011

Science and the Imagination

The New Yorker picked up my NYT column for a piece about science and the imagination. Here's an excerpt:

"Our job is not to predict the future. Rather, it's to suggest all the possible futures—so that society can make informed decisions about where we want to go." That's Robert J. Sawyer writing in Slate last week, in an essay called "The Purpose of Science Fiction." Sci-fi, Sawyer argues, isn't purely "fi." Sci-fi writers open public discourse on real-world scientific developments, advise governmental organizations like NASA and the Department of Homeland Security, and ask philosophical questions that lab-bound scientists are rarely able to.

Of course, it isn't as dry as all that. The writer of science-fiction is an artist who happens to be interested in science, unless he is a scientist who happens to be interested in art. The line between the two wasn't always drawn as thickly as it is today. Alchemists obviously blended the two, but there are more recent examples, too. A blog post that ran yesterday on the Times Web site, by Richard Conniff, covers certain nineteenth-century naturalists who used whimsical language to describe their discoveries (e.g. Charles Darwin), and nineteenth-century whimsicalists who used scientific language in their stories (e.g. Lewis Carroll). "What's the explanation for this intimate connection between science and nonsense?," Conniff wonders:

Scientists are of course somewhat human. So perhaps it should be unsurprising that they can sometimes have fun with — or make fun of — their own work. But in the 19th century that work — describing species no one had ever imagined — was also often fantastical. It is hard for us now to appreciate just how strange and wondrous the world seemed. It was as if someone you know had joined an expedition to Alpha Centauri and come back years later with first-hand accounts of Wookiees, Ewoks and Kowakian monkey-lizards. But in the great age of biological discovery, the returning travelers actually brought back specimens. Their weird creatures were real.

Perhaps because we no longer get quite the same shock from specimens found in nature, we have become adept at conjuring up weird specimens of our possible futures and calling them real.

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2011/01/science-non-fiction.html#ixzz1Ce10OXGA

January 30, 2011

On The Origin of Slithy Toves

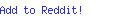

A highly fanciful 1833 representation of a South American monkey

Here's my latest Specimens column for The New York Times, based on my new book The Species Seekers:

When my children were small, we often read them Edward Lear's "The Jumblies," a not very edifying book of nonsense that we all loved. The Jumblies were wildly impractical souls who

… sailed away in a Sieve, they did,

In a Sieve they sailed so fast,

With only a beautiful pea-green veil

Tied with a riband by way of a sail,

To a small tobacco-pipe mast …

Back then, I was often away from home for weeks at a time, traveling in distant countries with biologists whose work sometimes required them to do the equivalent of sailing in a sieve. One botanist, for instance, recalled flying out of a war zone in a cargo plane that also carried a pig tied to a 55-gallon drum of gasoline. The Jumblies would have been right there (and probably flicking ashes from their cigars).

A pigeon by Lear

But it never occurred to me that there might be a direct connection between the two worlds of nonsense verse and biology. Then one day I picked up an old print of a tropical pigeon species and noticed the "E. Lear" in the bottom corner. Though he is celebrated today mainly as the author of such works as "The Owl and the Pussycat," Lear had started out as a naturalist. His first book, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots, drew favorable comparisons with Audubon when he published it in 1832, at age 19.

Like many naturalists, Lear described the natural world not just in literal-minded scientific detail, but also in fanciful doodles and verse. And when this blossomed into books for children, he often dispatched his characters, like naturalists, on wild explorations to the back of beyond. He also had them devote considerable energy to collecting the oddities of the country:

And they bought a Pig, and some green Jack-daws,

And a lovely Monkey with lollipop paws,

And forty bottles of Ring-Bo-Ree,

And no end of Stilton Cheese.

Nonsense was almost a byproduct of natural history. The twin themes of exploration and taxonomy, were "present in the genre as a whole, even in Lewis Carroll, who had no special interest in the subject," according to the French scholar Jean-Jacques Lecercle, in his 1994 book Philosophy of Nonsense: "The reader of 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland' is in the position of an explorer: the landscape is strikingly new … and a new species is encountered at every turn, each more exotic than the one before. Nonsense is full of fabulous beasts, mock turtles and garrulous eggs."

Such fanciful creatures sometimes turned up even in serious scientific work. In his "History of British Star-fishes, and other animals of the class Echinodermata," for instance, the naturalist Edward Forbes began one chapter with an illustration of Cupid in a sea-going chariot drawn by a pair of sea creatures with bodies like snakes and heads like sea urchins (they were Ophiuridae). Another chapter ends with Puck playing his pipe for a couple of dancing brittle-stars, one of which actually rests the back of a "hand" against out-thrust "hip." Elsewhere, he drew a stingray smoking a pipe and winking.

In Lecercle's view, Charles Darwin himself could sound as whimsical as Lewis Carroll; for instance, when he wrote about pulling the tail of a lizard in the Galapagos: "At this he was greatly astonished, and soon shuffled up to see what was the matter; and then stared me in the face, as much as to say, 'What made you pull my tail?'" Likewise, in Patagonia, Darwin and his companions communed with the camel-like guanacos: "That they are curious is certain; for if a person lies on the ground, and plays strange antics, such as throwing his feet up in the air, they will always approach by degrees to reconnoitre him." Darwin was only 23 at the time, not the gloomy eminence of later years, but Lecercle likes the idea "that the famous scientist should behave like Lear's 'Old Man of Port Grigor', who 'Stood on his head till his waistcoat turned red.' "

So what's the explanation for this intimate connection between science and nonsense?

Scientists are of course somewhat human. So perhaps it should be unsurprising that they can sometimes have fun with — or make fun of — their own work. But in the 19th century that work — describing species no one had ever imagined — was also often fantastical. It is hard for us now to appreciate just how strange and wondrous the world seemed. It was as if someone you know had joined an expedition to Alpha Centauri and come back years later with first-hand accounts of Wookiees, Ewoks and Kowakian monkey-lizards. But in the great age of biological discovery, the returning travelers actually brought back specimens. Their weird creatures were real.

When they told their tales about riding on the back of a caiman, or waking up from an al fresco nap to find that a gigantic condor had mistaken them for cadavers, it must have seemed even to them that they had traveled through the looking glass.

Near the end of his life, with his adventures as an explorer far behind him, the great field naturalist and evolutionist Alfred Russel Wallace built a house in a Dorset village for his daughter, to be joined by his wife after his death. He named it Tulgey Wood, after the haunt of the jubjub bird and the frumious bandersnatch in Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky":

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

Nowadays when I read that poem, I sometimes imagine Wallace hiding behind a tree in Tulgey Wood, peering out and chortling to himself — "Oh frabjous day! Calloo! Callay!"— at the magical but very real world he had been granted the privilege to know.

January 26, 2011

Clearing Up The Chaos in the Genital Parking Lot

Harvard researcher Naomi Pierce and her co-authors have just published a paper vindicating a far-reaching theory about butterflies proposed by Vladimir Nabokov, who was a lepidopterist as well as a novelist. In a nice article in the New York Times, Carl Zimmer writes:

He published detailed descriptions of hundreds of species. And in a speculative moment in 1945, he came up with a sweeping hypothesis for the evolution of the butterflies he studied, a group known as the Polyommatus blues. He envisioned them coming to the New World from Asia over millions of years in a series of waves.

Few professional lepidopterists took these ideas seriously during Nabokov's lifetime. But in the years since his death in 1977, his scientific reputation has grown. And over the past 10 years, a team of scientists has been applying gene-sequencing technology to his hypothesis about how Polyommatus blues evolved. On Tuesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, they reported that Nabokov was absolutely right.

Nabokov once described the years he spent working as a professional lepidopterist at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology as "the most delightful and thrilling in all my adult life." He found the work so rapturously diverting that at one point Vera, his wife, had to speak to him sternly about his true calling. Sulking, Nabokov pulled the manuscript of his latest novel out from under a pile of butterfly articles and recollected that, oh, yes, he could write, too.

You can read more about his ideas on classification and what I once termed "chaos in the genital parking lot" in a previous Times article I wrote, about the book Nabokov's Blues. It also reminds me of a passage I included in my book The Species Seekers, but ultimately had to omit because I could not locate a proper source to grant me reprint permission:

Nabokov once asserted that the satisfaction of naming a new butterfly species ("I found it and I named it …") exceeded even literary acclaim:

Dark pictures, thrones, the stones that pilgrims kiss,

poems that take a thousand years to die

but ape the immortality of this

red label on a little butterfly.

To be a naturalist was to play a part in building a great and permanent body of knowledge. But, significantly, he chose to make this point in a poem.

OTHER READING:

An interesting web site says the butterfly in question was Nabokov's pug But you can't name a species after yourself, and the pug was named for him by someone else. See also.

The new paper on genetic analysis is by Vila, R., C. Bell, et al "Phylogeny and palaeoecology of Polyommatus blue butterflies show Beringia was a climate-regulated gateway to the New World" Proc. R. Soc. B published online before print January 26, 2011, doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2213