Richard Conniff's Blog, page 110

February 14, 2011

The Species Seekers Quiz: Wallace's House of Rest

After spending a dozen years in the tropics and making his reputation as the greatest field biologist of the nineteenth century, Alfred Russel Wallace later gave this name to the house where he retired:

After spending a dozen years in the tropics and making his reputation as the greatest field biologist of the nineteenth century, Alfred Russel Wallace later gave this name to the house where he retired:

1. Darwinia, to honor his co-discoverer of the theory of natural selection (though his wife Annie had suggested Wallacea).

2. Umbraculum, from the Latin word for a place of quiet retirement.

3. Tulgey Wood, after a nonsense verse by Lewis Carroll.

4. Birdwing, for his discovery of the spectacular Wallace's golden birdwing butterfly.

And the answer is:

The worlds of species seeking and nonsense verse were surprisingly interconnected (you can read about it in The Species Seekers, Chapter 13, "A Fool to Nature" ). Wallace was so enamored of Lewis Carroll's work that, late in life, with his travels to the Amazon and the East Indies far behind him, he named his house Tulgey Wood, after the haunt of the jujub bird and the frumious bandersnatch in "Jabberwocky":

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

Here's a picture of the house at 149 Lower Blandford Road, Broadstone, Dorset, and here's the Google map. Wallace built Tulgey Wood in 1908 and died there five years later.

And finally, click here to see more of the creatures in jubjub artist David Elliot's excellent menagerie.

February 13, 2011

Race, Sex & The Trials of a Young Explorer

Here's the latest column in my series for The New York Times, based on my book The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth:

In 1859, Paul Du Chaillu, a young explorer of French origin and adopted American nationality, wandered out of the jungle after a four-year expedition in Gabon. He brought with him complete specimens of 20 gorillas, an animal almost unknown outside West Africa. The gorilla's resemblance to humans astonished many people, especially after Darwin published On the Origin of Species later that year. The politician Edwin M. Stanton was soon calling Abraham Lincoln "the original gorilla" and joking that Du Chaillu was a fool to have gone to Africa for what he could as easily have found in Springfield, Ill.

But the more common way to deal with our resemblance to monkeys and apes then was to fob it off onto other ethnic groups — typically black people, or sometimes the Irish. A few white scientists even purported to find physiological evidence, in the configuration of the skull, for classifying other races as separate species, not quite as far removed as Caucasians from our primate cousins. This undercurrent of scientific racism would play out to devastating effect in Du Chaillu's own life.

When Du Chaillu arrived in London for the 1861 publication of his book, "Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa," he became the most celebrated figure of the season, and then, overnight, the most notorious. He was, by all accounts, a charismatic presence, about 30 years old, with a thick moustache, a prominent brow, and bright, flashing eyes. He also had a gift for colorful lectures about hunting fierce animals and befriending cannibals.

But scientists were soon ripping him to bits in the British press, saying that he exaggerated his own adventures and gave too little credit to other explorers, including some he plagiarized. Many of these complaints seem to have been valid. In particular, Du Chaillu's depiction of the gorilla as a ferocious monster — "some hellish dream creature" — grossly distorted the image of these generally placid animals. (His stories were still around decades later serving as raw material for the Hollywood legend of King Kong.)

The ferocity of the attack on Du Chaillu that spring and summer of 1861 went well beyond ordinary academic bickering. Each week for more than a month, John E. Gray, keeper of zoology at the British Museum, sent a lengthy letter to The Athenaeum magazine denouncing Du Chaillu. Other critics eagerly piled on. Newly professional scientists may simply have wanted to distance themselves from the taint of amateurism. That seems to have been one reason Gray made a minor career out of disparaging field naturalists. Darwin, who rarely spoke ill of anyone, would later call him an "old malignant fool" for it. The attack on Du Chaillu was also a way for Gray to undercut his rival (and boss) at the British Museum, the anatomist Richard Owen, one of Du Chaillu's sponsors in London.

But as I was researching my book The Species Seekers, I kept coming across hints of an uglier motive for the attack on Du Chaillu, based on race. A merchant in Gabon made the cryptic assertion that he possessed "from reliable sources, information the most exact as to [Du Chaillu's] antecedents." Others whispered, as The New York Times reported, that "the suspicion of negro sympathies hangs around him in many ways." Du Chaillu presented himself as a white man, born in Louisiana, and an almost compulsive awareness of race runs through his book: "'You are the first white man that settled among us, and we love you,'" a village chieftain declares at one point. "To which all the people answered, 'Yes, we love him! He is our white man, and we have no other white man.' "

But the truth seems to be that his mother was a woman of mixed race, possibly a slave, on the Indian Ocean island of Réunion, where his father had been a merchant and slaveholder. Concealing this background, the historian Henry H. Bucher Jr. has written, was "an understandable choice during the heyday of scientific racism." In fact, Du Chaillu's expedition to Gabon had been sponsored by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, then the center of scientific racism. (Samuel G. Morton kept a vast collection of skulls there, "the American Golgotha," for the purpose of racial comparisons.) The "mysterious and rapid" end to Du Chaillu's close association with the Academy in 1860 may have resulted, says Bucher, from "a committee member's discovery of his maternal ancestry."

But the truth seems to be that his mother was a woman of mixed race, possibly a slave, on the Indian Ocean island of Réunion, where his father had been a merchant and slaveholder. Concealing this background, the historian Henry H. Bucher Jr. has written, was "an understandable choice during the heyday of scientific racism." In fact, Du Chaillu's expedition to Gabon had been sponsored by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, then the center of scientific racism. (Samuel G. Morton kept a vast collection of skulls there, "the American Golgotha," for the purpose of racial comparisons.) The "mysterious and rapid" end to Du Chaillu's close association with the Academy in 1860 may have resulted, says Bucher, from "a committee member's discovery of his maternal ancestry."

A letter sent to an English friend in the thick of the Du Chaillu controversy supports this theory. George Ord, an officer of the academy, wrote that some of his learned colleagues had taken note when Du Chaillu was in Philadelphia of "the conformation of his head, and his features" and detected "evidence of a spurious origin." Ord added: "If it be a fact that he is a mongrel, or a mustee, as the mixed races are termed in the West Indies, then we may account for his wondrous narratives; for I have observed that it is a characteristic of the negro race, and their admixtures, to be affected to habits of romance."

In England, the mathematician Augustus de Morgan echoed these feelings. He found the running battle over Du Chaillu so entertaining that he sent a congratulatory note to his friend William Hepworth Dixon, editor of The Athenaeum, calling "this Gorilla matter … a godsend" for a journal that had begun to seem stodgy. Then, without stating the racial gossip outright, he drove the point home with a joke based on the old urban legend of a brewer who serves up an unusually good batch of beer, only to find a dead body at the bottom of the vat. But in this case, the body belonged to a black man. That's the secret for lively reading, De Morgan concluded: "A negro in the vat every time!"

Though it's only conjecture, sex may also have played a role in the savaging Du Chaillu endured in England. He was an enthusiastic socializer, whose address books in later life were full of notes about "calls to make" "notes to send," and new acquaintances, both male ("lawyer good fellow") and female ("of medium height with dark chestnut hair … an exquisite figure … graceful"). A friend later passed the word "sub rosa" to an acquaintance that Du Chaillu was "rather too fond of women."

Curiously, the same issues of The Athenaeum in which the attack on Du Chaillu was playing out also featured a running plagiarism fight about a stage melodrama called "The Octoroon." It told the story of a dazzling New Orleans beauty "educated in every refinement and luxury" who was "almost a perfect white, her mother being a quadroon." In all three contesting versions of this tale, an "underhanded Yankee overseer" seeks to possess the heroine on the slave market. And in each case, a dashing sea captain foils the nefarious plot and carries the beauty off to freedom. Audiences apparently felt comfortable taking the heroine's side because she was seven-eighths white. But what if the sexes had been reversed, with a white woman falling for a mixed-race man — a man like Du Chaillu, say?

Readers needed only to turn the pages of The Athenaeum to find out.

Du Chaillu did not collapse in the face of this attack. Instead, he returned to Gabon to defend his work. The new expedition was a nightmare, but he brought back one particular set of specimens that pleased him. On his previous trip, he had tentatively proposed a new genus of giant river otter, Potamogale, based on the tattered skin of an animal he had shot. Gray had sneeringly classified it as a rodent instead, with the derisive name Mythomys. But it turned out that the field naturalist, not the museum curator, had come closer to the truth. After much throat-clearing on Gray's behalf, a professor at Edinburgh University concluded, "Mr. Du Chaillu's name of Potamogale stands: it has thus precedence over Gray's name of Mythomys; and the laws of natural-history nomenclature compel us to accept it."

For a flawed explorer vilified at least partly on account of another classification — his race — it was a vindication.

Fast Tongue, Slow Suck? A Valentine's Day Blog.

Two bits of biological research should have you contemplating the splendid things tongues can do.

First, scientists have come up with the one factoid you have all been pining to know: The animal with the fastest tongue on Earth is a giant palm salamander from Central America, Bolitoglossa dofleini.

Bolitoglossa? Isn't that Greek, or maybe Spanish, for bullet tongue?

The salamander actually fires its tongue more like an arrow, propelling it with the energy stored by stretching elastic fibers in its mouth. In fact, firing the tongue releases more than 18,000 watts of power per kilogram of muscle, according to Stephen Deban of the University of South Florida in Tampa. That's almost double the previous record of 9,600 watts per kilogram, held by the Colorado River toad. Either way, their insect prey die. You can see a termite take the fall at Deban's web site, While you're there, look around the site for cool photos and diagrams. The shot of the cricket getting plucked off a trapeze is highly entertaining.

Meanwhile, Brendan Borrell at the University of California, Berkeley, has been studying orchid bees. These tiny insects have evolved extraordinarily long tongues, to gain exclusive access to the nectar from deep-throated tropical flowers. By measuring the feeding rate of different bee species at artificial flowers in Costa Rica and Panama, Borrell found that the bees with long tongues are slow feeders. That's because it really is hard work sucking nectar through a long straw. But they sacrifice speed, he says, because these flowers are extraordinarily nutritious, providing up to ten times the quantity of nectar provided by typical bee flowers.

It makes me wonder about the time Darwin was looking at 15-inch-long orchid flower from Madagascar, Angraecum sesquipedale, and predicted that there had to be an insect with a tongue that long to pollinate it. Forty years after Darwin's death, scientists discovered the hawkmoth they named Xanthopan morganii praedicta, to honor Darwin's prediction. It unfurls its incredibly long tongue in flight and inserts it deep into the flower to feed. But in the video I've seen, the hawkmoth gets what it wants pretty quickly and moves on. So what's the story, Brian? Are they watering the nectar in Madagascar?

But. o.k. I will leave you to daydream about what it might be like if your mate had a tongue as fast as a giant palm salamander's, and as patient and probing as an orchid bee's. Happy Valentine's Day.

My Book Cover Avatars

I've just received a copy (cover at left) of the Japanese edition of Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time–My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals, and apparently the art department there imagines me as a muscular Cat Stevens type in a 1920s bathing suit. Previously, the U.S. paperback of The Natural History of the Rich: A Field Guide (cover in middle) depicted me as a short-sighted Jewish anthropologist in a pith helmet, apparently specializing in the earwax of plutocrats. I am not complaining: The Chinese edition of The Ape in the Corner Office (cover at right) is an actual author photograph, during a thoughtful moment in my study.

The Father of All Wakeup Calls

February 12, 2011

God is a Tree Hugger

When I published a piece recently in the New York Times about how rapidly species are going extinct, my religiously inclined sister–my own sister!–replied, "Who's to say they shouldn't have gone extinct?"

God came to mind.

Maybe it's pandering, but here is a selection of passages from the Bible that clearly argue for a conservationist ethos:

"The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it." (Genesis 2:15)

"You must keep my decrees and my laws…. And if you defile the land, it will vomit you out as it vomited out the nations that were before you." (Leviticus 18:26, 28)

"The land itself must observe a sabbath to the Lord. For six years sow your fields, and for six years prune your vineyards and garner their crops. But in the seventh year the land is to have a sabbath of rest, a sabbath to the Lord…. The land is to have a year of rest." (Leviticus 25:2-5; cf. Exodus 23:10-11)

"The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine; with me you are but aliens and tenants. Throughout the land that you hold, you shall provide for the redemption of the land." (Leviticus 25:23-24)

"If you follow my statutes and keep my commandments and observe them faithfully, I will give you your rains in their season, and the land shall yield its produce, and the trees of the field shall yield their fruit." (Leviticus 26:3-4)

"You shall not pollute the land in which you live…. You shall not defile the land in which you live, in which I also dwell; for I the LORD dwell among the Israelites." (Numbers 35:33-34)

"If you besiege a town for a long time, making war against it in order to take it, you must not destroy its trees by wielding an ax against them. Although you may take food from them, you must not cut them down. Are trees in the field human beings that they should come under siege from you?" (Deuteronomy 20:19)

And when we defile the land, God is surely pissed:

"I brought you into a plentiful land to eat its fruits and its good things. But when you entered you defiled my land, and made my heritage an abomination." (Jeremiah 2:7)

"How long will the land lie parched and the grass in every field be withered? Because those who live in it are wicked, the animals and birds have perished." (Jeremiah 12:4)

"It will be made a wasteland, parched and desolate before me; the whole land will be laid waste because there is no one who cares." (Jeremiah 12:11)

"Is it not enough for you to feed on the good pasture? Must you also trample the rest of your pasture with your feet? Is it not enough for you to drink clear water? Must you also muddy the rest with your feet?" (Ezekiel 34:17-18)

"There is no faithfulness, no love, no acknowledgment of God in the land. There is only cursing, lying and murder, stealing and adultery; they break all bounds, and bloodshed follows bloodshed. Because of this the land mourns, and all who live in it waste away; the beasts of the field and the birds of the air and the fish of the sea are dying." (Hosea 4:1-3)

"We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time." (Romans 8:22)

And the destruction we are bringing down on ourselves is going to be almighty bad:

"He turned rivers into a desert, flowing springs into thirsty ground, and fruitful land into a saltwaste, because of the wickedness of those who lived there." (Psalm 107:33-34)

"Woe to you who add house to house and join field to field till no space is left and you live alone in the land. The LORD almighty has declared in my hearing: 'Surely the great houses will become desolate, the fine mansions left without occupants. A ten-acre vineyard will produce only a bath of wine, a homer of seed only an ephah of grain.'" (Isaiah 5:8-10)

"The earth dries up and withers, the world languishes and withers, the heavens languish together with the earth. The earth lies polluted under its inhabitants; for they have transgressed laws, violated the statutes, broken the everlasting covenant. Therefore a curse devours the earth; its inhabitants suffer for their guilt." (Isaiah 24:4-6)

"You have polluted the land with your whoring and wickedness. Therefore the showers have been withheld, and the spring rain has not come." (Jeremiah 3:2-3)

"The nations were angry; and your wrath has come. The time has come for judging the dead, and for rewarding your servants the prophets and your saints and those who reverence your name, both small and great-and for destroying those who destroy the earth." (Revelation 11:18)

If I may conclude with a little of what Bible scholars call exegesis, here's the moral: You may argue all you want about how the Earth and its species originated, but first take care of this extraordinary world we have been given. Bible-thumpers should be Tree-huggers.

February 11, 2011

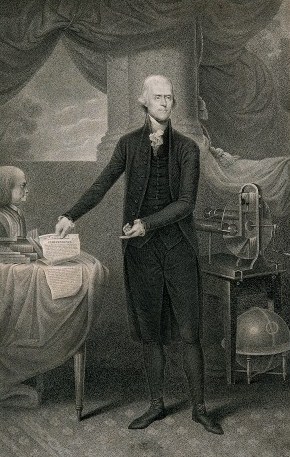

Benjamin Franklin to the Rescue

Ben Franklin as Volunteer Fireman and American Superhero

In mid-18th century, the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, promulgated the theory of American degeneracy. He declared that "a niggardly sky and an unprolific land" caused species in the New World—including humans—to become puny and degenerate. "No American animal can be compared with the elephant, the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus," he sniffed in 1755. Even the American Indian is "small and feeble. He has no hair, no beard, no ardour for the female." Because Buffon was one of the most widely read authors of the 18th century, his theory became conventional wisdom, at least in Europe.

Clearly offended, Thomas Jefferson (who stood 6-foot-2) constructed elaborate tables comparing American species with their puny Old World counterparts—three-and-a-half pages of bears, bison, elk and flying squirrels going toe-to- toe. When Jefferson sailed to Paris in 1784 to represent the new United States, he packed "an uncommonly large panther skin" with the idea of shaking it under Buffon's nose. He later followed up with a moose. (Buffon promised to amend his errors in the next edition of his book, according to Jefferson, but died before he could do so.)

Benjamin Franklin probably made the point more effectively with a deft gesture.

At a dinner in Paris, a diminutive Frenchman (in recounting the story, Jefferson described him as "a shrimp") was enthusiastically preaching the doctrine of American degeneracy. Benjamin Franklin (5-foot-10) sized up the French and American guests, seated on opposite sides of the table, and proposed: "Let us try this question by the fact before us…. Let both parties rise, and we will see on which side nature has degenerated."

The Frenchmen muttered something about exceptions proving rules–and remained seated.

Read more in The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth by Richard Conniff.

A Different Sort of Online Chat

I'm always interested in the biological basis of our behaviors, even for instance, when we are online. So browsing around this morning, I came across this colorful history of the word chat in World War I, from Bookrags:

Throughout the war, soldiers fought, ate, slept, washed, and relieved themselves in narrow trenches surrounded by dead, decomposing bodies and hungry diseased rats. To make matters worse, the body louse, also known as the "chat," was rampant. Since lighting fires on the front lines was prohibited because they would attract sniper fire, soldiers often had to huddle in close groups in cold weather, thus enabling infestation. Besides being a vector for diseases like typhus fever, which killed millions of German and Russian troops on the Eastern Front, the body louse can spread very quickly, producing up to twelve eggs per day. When conditions allowed, soldiers made social events of picking off these lice from clothing hair, and skin; these events were often called "chats" or "chatting up."

I wish I could say that our gchats are actually just a vicarious form of social delousing. But with regret, here's a broader account of the origins of chat from the etymology site Podictionary:

The Oxford English Dictionary explains the old meanings include "to utter familiarly; to talk in a gossiping way" and "to talk in a light and informal manner."

Much of the live chat that goes on is certainly light and informal.

The word chat first appeared in English in the early 1400s as an abbreviation for chatter.

Chatter had, and still has, what the OED calls a more "depreciative" meaning than we assign to chat.

You can have a good chat with a friend but it's those other people who are chattering about nothing in particular.

Chatter appeared in English back in the early 1200s and is said to be onomatopoeic.

As if anticipating Twitter 800 years ago the first meaning we have in the OED for chatter relates to birds uttering a rapid string of chirps.

It's the rapid succession of sound that makes for chattering.

People not only chatter when talking in groups about juicy gossip but their teeth chatter when they are cold; making a quick series of clicks.

This teeth chattering appeared in the 1400s but it is why I said that participating in online chat is etymologically accurate. Typing as you live chat does make an ongoing quick series of clicks as you hammer away at the keyboard.

It was March 1985 that the OED points to as the emergence of the new meaning of chat. From the magazine Today's Computers

"Chat, a mode [of computers connected as a Local Area Network] in which two or more users may type messages on each other's terminals, enabling back-and-forth conversations through the network without waiting for electronic mail to be sent and received."

February 9, 2011

The President Discovers a Species

Model of a giant ground sloth

You know about U.S. presidents who have had species named in their honor. President George W. Bush, for instance, was lucky to attain scientific immortality on the back of a slime mold beetle, Agathidium bushi. But which president actually described a new species himself?

A. Teddy Roosevelt, who bagged a new species of piranha during his Amazonian explorations.

B. John Quincy Adams, who discovered a new catfish while skinnydipping in the Potomac.

C. Thomas Jefferson, whose work on mastodons helped make the elephant the symbol of the Republican Party.

D. Rutherford B. Hayes, who discovered a new songbird while out hunting (and shot it).

And the answer is …

Jefferson as statesman and scientist

The only American president to have named a new species himself was Thomas Jefferson. In 1797, while still serving as vice president, he described a species based on a huge claw recovered from a cave in West Virginia. Jefferson, who was obsessed with the idea of finding big, fierce creatures in the American wilderness, thought it was a kind of lion three times larger than its African counterpart. He gave it the genus name Megalonyx.

Unfortunately, it later turned out to be a giant ground sloth. But it was at least a new species, and a French anatomist graciously named it jeffersoni after the president.

Because of this work, Jefferson also gets credit for launching the science of vertebrate paleontology in North America. Incidentally, as president of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Jefferson also sponsored important work on mastodons. But it had nothing to do with the eventual GOP use of pachyderms as their symbol.

You can read more about it in The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth.

Note: The model giant ground sloth, named Clawd, is on display at the Virginia Museum of Natural History

February 7, 2011

Lost and Gone Forever–The List?

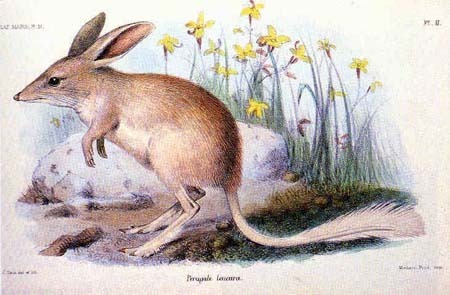

Australia's lesser bilby, now extinct

My "Specimens" column for this week in The New York Times is about species that have gone extinct over the past 30 years. So it occurred to me to make something like my Wall of the Dead–A Memorial to Fallen Naturalists, but for lost plants and animals.

Then I realized I would go insane doing it.

And also get very depressed. The estimate I have heard is that 30,000 species are now disappearing each year, most without ever having been discovered. At the risk of seeming sentimental, it makes me think of Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," where he tries to imagine the lost potential of the rude country folk–the "mute, inglorious Milton"– now buried "beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade":

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway'd,

Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre.

That line about the yew-tree is a nice coincidence. Like a lot of species now vanishing, yews were deemed worthless, except for ornamental purposes. Then in the 1970s, researchers discovered that taxol, from yews, was a powerful anti-cancer drug. It now saves and extends the lives of tens of people who would otherwise have died. In purely commercial terms, a very crude way to value a species, taxol is now a $1.6 billion a year product.

But almost none of the plants now rapidly going extinct has been studied to see if they might offer such benefits.

I think the best thing I can do here is collect resources on extinct and threatened species. Here's a start:

ARKive is a unique global initiative gathering the very best films and photographs of the world's threatened species into one centralized digital library free to all at www.arkive.org

Conniff, Richard, The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth (Norton, 2011), includes chapters on the rise of the science of extinction.

Eldridge, Niles, "The Sixth Extinction" article

Flannery, Tim and Peter Schouten A Gap in Nature. A handsomely illustrated collection of some of what we have lost, published by William Heinemann (2001).

Maas, Peter, "The Sixth Extinction" web site

Sartore, Joel. Rare: Portraits of America's Endangered Species (National Geographic)

Wikipedia has a collection of extinct species lists here.

More to come. Please send your suggestions.