Richard Conniff's Blog, page 109

February 22, 2011

The Brain Cutter

Here's my profile of Harvey Cushing, published recently in the Yale Alumni Magazine:

Deep beneath the stacks of the Yale medical school library, a kind of grotto venerates the human brain. It's a memorial to an era when surgery on "the closed box" of the human skull was far more mysterious, even macabre, than it seems today. It's also a celebration of one man who made it less so, essentially inventing modern brain surgery by his odd blend of audacity and painstaking care with scalpel, drill, saw, and clamp.

You get a hint of what lies beneath on the stairway down, where a large photograph from 1930 shows a 24-year-old surgical candidate in hospital pajama bottoms, facing the camera and displaying symptoms of the form of gigantism called acromegaly. Surgeon Harvey Cushing, Class of 1891, stands at his side. He is an older and much smaller man, facing the patient, one knee canted forward, one hand in the jacket pocket of a carefully tailored glen-check suit. With his other hand, he holds the giant delicately by two fingers, as if to lead him to his fate. (The patient, a farm laborer, had been told by another doctor that he would "die if anyone operated on his pituitary." In fact, he was able to write Cushing, three years after surgery, wishing him "high spirits and the best of health.")

Descend one more flight of stairs, and you encounter the twisted skeleton of an acromegaly victim from 1896, before surgical intervention could alter the insidious progress of the disease. It sprawls on its back, chest hugely enlarged, feet deformed, head turned to one side as if to greet the visitor with a howl of dismay. And one level further down, you pass through the key-carded door of the Cushing Center itself, newly opened this summer after a construction and conservation project costing just over $1 million. And then—lights, camera, action—you descend a little farther, along a ramp, past a stage-lit chorus line of brains and tumors suspended in jars of glowing amber-tinted fluid. In places, the brains and photographs of their former owners pose side by side, in mute homage to the work of the difficult, demanding, and often heroic Dr. Cushing.

A photograph survives of Harvey Williams Cushing as a Yale undergraduate in 1889, doing a perilous back flip off the stoop of a university building. It was one of the rare frivolous moments in an otherwise intensely purposeful life. Cushing, the product of three generations of physicians in a wealthy Cleveland family, performed surgery as a senior at Yale, extracting the brain of a dog found wandering on campus. (Notions of ethical experimentation, on animals and humans alike, were nebulous then, though as a doctor Cushing would at least anesthetize animals before operating on them, an indulgence some European counterparts deemed frivolous.) He went on to Harvard Medical School, and spent most of his career at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and later at Harvard's Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, before eventually returning to Yale.

In the late 1890s, when Cushing was starting out as a surgical resident, the skull was mostly "attacked in desperation and with dismal outcomes," Michael Bliss writes in his 2005 biography Harvey Cushing: A Life in Surgery. Surgeons lacked imaging technologies to determine where in the brain a problem might lie, and they were ignorant about what neurological functions might be compromised by a careless move en route. Most attempts to operate ended ignominiously in bleeding, uncontrollable bulging of brain tissue, infection, and death. Young Cushing failed, too, with a pregnant woman shot in the head, and with a 16-year-old girl whose pituitary tumor eluded him in three attempts. These losses left him soul-shaken. But "having looked at the brain," Bliss writes, Cushing went on in the first decade of the new century to learn "how to gain access to it, relieve it, and let it heal." He thus became "the father of effective neurosurgery." ("Ineffective neurosurgery," Bliss adds, "had many fathers.")

Cushing himself attributed his success to meticulous care, rather than brilliant innovation. He prided himself on "perfection of anesthesia, scrupulous technique, ample expenditure of time, painstaking closure of wounds without drainage, and a multitude of other elements, which so many operators impatiently regard as trivialities." The delicate nature of the work made slow going essential. "An operator who persists in taking dangerous curves at high speed will be the cause of a serious or fatal accident some day," he declared, "whether he is driving an automobile or opening a skull." Cushing worked "almost ritualistically," according to Bliss, shaving and draping the patient's head himself, and doing the routine closing of the wound afterwards. "He was especially pleased if there were no blood stains on the drapes when the operation ended." Such care enabled him to go where other surgeons did not dare, and get far better results. Without adequate lighting or magnification, he reduced his mortality rate to less than 10 percent, in an era when renowned brain surgeons elsewhere admitted to losing a third to half their brain patients.

But Cushing was also quick to invent surgical techniques and exploit new technologies. He introduced the blood pressure cuff to American medicine, after spotting the device in Italy during a year abroad, and he soon made it an essential tool for monitoring the status of surgical patients. He also adapted the idea of the inflatable cuff into a pneumatic tourniquet, wrapped around the skull before surgery to prevent heavy bleeding from the scalp. To control bleeding within the brain itself, he pioneered the use of silver surgical clamps in neurosurgery and also experimented with blood clots and living tissue to induce coagulation. Much later in his career, he introduced electrocauterization to brain surgery, using a pistol-shaped device that could cut and coagulate in the same motion. He described it as "powerful enough to electrocute a mastodon and pretty nearly as big." It gave off the smell of burning tissue, produced shocks in early versions, and on one occasion lit up the operating room with a blue flare of ether vapor. But Cushing was thrilled at his newfound ability to remove large, heavily vascularized tumors: "I am succeeding in doing things inside the head that I never thought it would be possible to do."

The other key to his success, along with the caution and audacity, was meticulous record keeping. It started when he was assisting with surgery as a student, using a sponge to administer ether, and the patient died in front of the entire class. Appalled and mortified, Cushing and a classmate soon developed "ether charts," to keep track of a patient's heart and respiration rates—his "first major contribution to medicine," according to a recent profile in the Journal of Neurosurgery: "Such charting revolutionized surgery by greatly curbing complications and deaths" from anesthesia. A few years later the young surgeon became infuriated over a second mishap, a pathology department's loss of a golf ball–size piece of brain tissue before he had had a chance to examine it. He demanded the right to retain all his own specimens, leading to the creation of the Cushing Brain Tumor Registry, a carefully maintained collection of tissues, detailed medical records, sketches, and patient photographs. His insistence, over the rest of his career, on almost compulsively recording what he saw enabled him to sort through irrelevant or inconsistent details and zero in relentlessly on essential facts. It also inadvertently documented the birth of neurosurgery.

In the course of inventing neurosurgery, Cushing also created the cult of the brain surgeon as high priest, difficult, demanding, devoted to his work above all else. "Not many men down here liked him," a Baltimore colleague wrote. "He rode roughshod over them and was ruthless. Yet he had his moments and could be as charming and delightful as anyone else. Only there weren't many such moments. … Tough hombre. Yeah, but one of America's immortals." If Cushing could be brutal to hospital staff, he was also extraordinarily self-sacrificing on behalf of patients. "A nurse never forgot the time a child who had been tracheotomized for diphtheria had his tube accidentally withdrawn and rushed into the hallway choking," Bliss writes. "Cushing took hold of the boy, put his mouth to the wound, sucked out the mucus, blood, and disease-membrane, then reinserted the tube."

Staffers who could live up to "the chief's" high standard earned his loyalty. Louise Eisenhardt, who started as a secretary in 1915, went on to become a physician herself, a rare accomplishment for a woman then, and possible only with Cushing's support. Trusted staffers tended to be intensely loyal in turn. When someone once proposed bypassing one of Cushing's fussy rules, a lab worker replied, "Orders is orders, and if Dr. Cushing says that the building should be burned down," it would soon lie in ashes.

Cushing's wife Kate and their five children paid the price for his devotion. Once, after he had made a visit home between bouts of travel and work, she wrote, "I couldn't talk to you Harvey—you weren't interested." And when he contemplated moving to Boston while she remained in Baltimore, she replied that they "would simply drift further and further apart—you absorbed in your work. I—in my work and possibly somebody else who happened to be interested in me a little." His reply surely did not soothe her: "An awful day—hot and muggy—a bad ganglion case—several foreign visitors on my chest—patients throwing fits at unfortunate moments … and not the least your depressing letter."

As "the chief" approached retirement age, Harvard treated him with an attitude his protégé and later biographer John Fulton characterized as "patronizing stupidity." Among Europeans, Fulton wrote, Cushing "is regarded as the outstanding figure in American medicine of this or any previous epoch. In Harvard he is merely a troublesome member of the medical faculty." Cushing left Harvard unceremoniously in 1932 and moved to Yale, bringing with him his priceless collection of more than 7,000 antiquarian medical books, and later the entire Tumor Registry. The books became the basis of the medical school's historical library. A new generation of neurosurgery students also continued to use the Tumor Registry as an educational tool for years after Cushing's death in 1939 (a heart attack at age 70, after lifting a weighty volume of a sixteenth-century illustrated human anatomy). But Cushing's methods inevitably began to seem antiquated, and the Tumor Registry, with all its strange neurological incunabula, got put away and forgotten.

Then one night in 1991, a group of medical students went drinking at Mory's, and someone passed along a story about a roomful of brains in the basement of their dormitory. Later that night, says Christopher Wahl '96MD, now an orthopedic surgeon, they went to investigate, spiritually fortified and still in their jackets and ties. Getting there meant clambering over ductwork, past barrels of food supplies for a former Cold War bomb shelter, and picking a lock with a paper clip. Then, in a room illuminated by bare lightbulbs, they found themselves amid shelf after metal shelf of brains and tumors in carefully labeled jars. Against a wall were rickety stacks of glass photographic images that struck Wahl, then a first-year med student, as "super-creepy"—patients with their hands splayed out across their chests in an almost cult-like pose, children stripped bare to reveal horrific deformities, people with heads blown out by the sort of tumors rarely seen in the modern medical era.

A few months later, Wahl took a course in medical history and another lightbulb came on, in his head. "I went to Dennis Spencer, then section chief of neurosurgery, and said, 'You know, Harvey Cushing's brains are in the sub-basement of the dormitory,' and he almost choked." Spencer says choking was a natural response to the notion of inebriated, lock-picking students visiting the storage room late at night. But he offered Wahl a yearlong fellowship to sort through the collection, and Wahl soon found himself moving from riveting photographs to records of the patients in the photographs to the specimens taken from their bodies. "It seemed so poignant," he says now. "Sometimes you need to have the patina of something being left and forgotten for a long time for it to be meaningful. You realize how much things have changed and how incredibly brave these patients were, and how much of an innovator Harvey Cushing was. He must have had a phenomenal ego to continue operating in the face of what was, when he began, almost always fatal surgery."

Soon after, Yale began a campaign to draw attention to the medical school's neurosurgical accomplishments. But an outside publicist fixated instead on brains in the basement, and the story ended up as a student caper on the front page of the Wall Street Journal ("Many Special Minds Are Found at Yale"). The university development office predictably flipped out, according to Wahl, demanding that he play up the academic research and hold the caper. They worried, he says, that the publicity would offend the Cushing and Whitney families (joined by the marriage of one of Harvey and Kate Cushing's daughters) and imperil the endowment supporting the medical school library, which had only recently become known as the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library.

For Spencer and Wahl, the larger worry was that someone would declare the Tumor Registry and its precariously stored jars of human tissue in formaldehyde a health hazard, to be destroyed. Late-night visits to the brain room meanwhile became a student ritual, with visitors now leaving their signatures on a "Brain Society" whiteboard: "José 'Hole in the Head' Prince," "Vivian 'full frontal lobe' Nereim," "Josh Klein-oid Process," and the unforgettable "Hana 'I don't even fucking go here' Capruso." The last may have been a reminder that the medical school couldn't count indefinitely on the good will of its students to keep the collection intact.

Spencer, now the Harvey and Kate Cushing Professor of Neurosurgery and chair of the Department of Neurosurgery, is a genial, white-bearded figure with a passion for Harley-Davidson motorcycles. He does not fit the "high priest" mold. When he's not in biker leathers, he wears silk suspenders, and a silver seahorse brooch on the pocket of his shirt. (The brooch, he says, belonged to his late wife and colleague, Yale neurologist Susan Spencer; its tail resembles the structure of the hippocampus, the focus of his work treating severe epileptic and other seizures.) During 2003–04, still fretting about the Tumor Registry, Spencer served as interim dean of the medical school.

"Institutions have things buried all over the place," he says, and one of the forgotten treasures he unearthed during his term was an endowment left by the grateful family of a Cushing patient, to protect his legacy. It had grown over 70 years, enough to put the medical school's staff photographer, Terry Dagradi, to work scanning and cataloguing and thinking about the glass photographic slides. In the days before CAT scans and MRIs, Cushing had used photographs as diagnostic tools, because certain disorders of the brain reveal their location by symptoms that show up in the face or in the cartilage of the hands and feet. But Dagradi was taken with the small human gestures that had slipped into what were meant purely as clinical photographs—the way one man holds a hand to the side of his face, bends his head to the opposite side, and winces, as if from an unbearable toothache; or the way an older woman holds her hand up in front of her, showing her palm, as if to say, "Don't touch me." "A lot of it was accidental," says Dagradi, now curator of the Cushing Center. Whoever took the pictures "wasn't trying to create an artistic image. But it's such a lovely time capsule."

The rediscovered endowment was also almost large enough, with additional help from the Cushing and Whitney families, to make a proper home for Cushing's legacy. The medical school eventually settled on an odd pie-slice of basement beneath the library and chose an idiosyncratic architect, Turner Brooks '65, '70MArch, an adjunct professor at the Yale School of Architecture, to bring it to life. "We all felt that going underground worked quite well," says Dagradi. "It doesn't really need light, and there's a mystery that Turner kept alive in this place that you felt when you were in the other place," beneath the dormitory.

The effect is a bit like a grotto, with the ramp sweeping you down and releasing you into what Brooks calls "the pools and back eddies" of the main floor, where undulating cabinet fronts hold drawers full of specimens—an old Chinese surgical kit, a box containing the skulls of human fetuses. Glass cases on top display some of Cushing's books—a first edition of Copernicus open to his model of the heliocentric universe, and another of Darwin's Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

"It's not like putting on headphones and getting a guided tour," says Brooks, "but you get pulled along by the current and make discoveries along the way. Gaston Bachelard in The Poetics of Space had this image about opening an armoire, and it keeps opening. You find drawers within drawers, and you hear a symphony playing somewhere inside." And all around the room, in a curving line, the brains look down.

Each jar had to be emptied, cleaned, refilled with new preservative, and sealed, says Dagradi, "and when we first started cleaning, it was like, 'Oh no, it's too clear. It's not going to have that beautiful honey color.'" But the specimens soon leached out into the new preservative and the jars took on their own individual glow. In places, they are like stained glass, particularly a glass wall of specimens that screens off a seminar room at the far end of the space. There, says Brooks, telemedicine will give future students a window on brain surgery around the world. But they'll also look back, from time to time, through the wall of specimens, and thus through the history of brain surgery as pioneered by Harvey Cushing.

This past June, members of the Society of Neurological Surgeons, which Cushing founded, came to New Haven from around the world for their annual meeting, and held a reception in the new Cushing Center. Brooks came, too, and brought his five-year-old daughter, who looked up in wonder at the long line of brains lit up around the room. "She said, 'Are they still thinking?' and the comment reverberated around the room," Brooks recalls. "And in my imagination, all the brains began to fizzle."

February 21, 2011

Why Scientists Should Not Be Spies

In a commentary on my "Species Seekers and Spies" column, Lukas Rieppel, a PhD candidate at Harvard, adds some interesting examples to the list of scientists who were also spies. But I was most impressed with this paragraph, in which Franz Boas gets at the fundamental problem of scientists using their research as a cover:

During World War One, the Columbia University Anthropologist Franz Boas serendipitously learned that Sylvanus Morley and a number of other archeologists were gathering intelligence for the United States Government. After the war, he wrote a strongly worded letter denouncing their actions to The Nation that was published in December, 1919. In it, he argued that espionage work and scientific research were fundamentally at odds, because "the very essence of [a scientist's] life is in the service of truth." As such, anyone "who uses science as a cover for political spying … prostitutes science in an unpardonable way and forfeits the right to be classed as a scientist." As a result of their unconscionable actions, he concluded, "every nation will look with distrust upon the visiting foreign investigator who wants to do honest work," thus making it all but impossible to conduct serious natural history research. Rather than having it's intended effect, though, the publication of this letter led to an official censure of Boas by the American Anthropological Association and led to his resignation from the National Research Council.

February 20, 2011

Species Seekers and Spies

Death's head sphinx moth

Here's the latest column in my Specimens series for The New York Times:

There's a scene early in the 2002 film "Die Another Day," where James Bond poses as an ornithologist in Havana, with binoculars in hand and a book, "Birds of the West Indies," tucked under one arm. "Oh, I'm just here for the birds," he ventures, when the fetching heroine, Jinx Johnson, played by Halle Berry, makes her notably un-feathered entrance.

It was an in-joke, of course. That field guide had been written by the real-life James Bond, an American ornithologist who was neither dashing nor a womanizer, and certainly not a spy. Bond's name just happened to have the right bland and thoroughly British ring to it. So novelist Ian Fleming, a weekend birder in Jamaica, latched onto it when he first concocted his thriller spy series in the 1950s.

The link between naturalists and spies goes well beyond Fleming, of course, and it might seem as if this ought to be flattering to the naturalists. While the James Bonds and Jinx Johnsons of spy fiction are trading arch sex talk in the glamour spots of the world, real naturalists tend to be sweating in tropical sinkholes, or wearing out their eyes studying the genitalia of junebugs. (That's not a joke, by the way: Genitalia evolve faster than other traits and often serve as the key to species identification, especially in insects. The Phalloblaster, a device worthy of Bond, was invented to make the job easier by inflating the parts in question.) And yet, as I was researching my book The Species Seekers, I found that naturalists don't actually like the connection at all. The suspicion that they may be spies just complicates the difficult job of getting access to habitats and specimens in foreign countries, which are often already leery of their odd collecting behavior. It can also get them jailed, or even murdered.

So is there a basis in real life for the persistent idea of the naturalist as spy? Spies have at times certainly pretended to be naturalists. The most public of them was Sir Robert Baden Powell, better known as founder of the Boy Scouts. As a British secret agent, he thought it clever to pose as "one of the exceedingly stupid Englishmen who wandered about foreign countries sketching cathedrals, or catching butterflies." His detailed maps of enemy fortifications were concealed within the natural patterns of butterfly wings and tree leaves, and he sometimes showed off these sketches to locals, secure in the sad knowledge that they "did not know one butterfly from another—any more than I do."

Rival nations and their spies have also frequently targeted natural history treasures. Persian monks visiting China in 552 A.D., for instance, brought back silkworm eggs concealed in a hollow cane. This pioneering act of industrial espionage established the silk trade in the Mediterranean and broke a longstanding Chinese monopoly. That kind of resource grab got repeated on the grand scale during the colonial era, for products from quinine to rubber, one reason international rules on collecting expeditions are now so strict.

Naturalists, or people with a naturalist avocation, have at times also had careers as spies. Maxwell Knight, the British counterintelligence spymaster (and one of the models for James Bond's boss M), actually worked on the side as a BBC natural history presenter and author. In the late 1950s, he hired a young man named David Cornwell to provide bird illustrations for one of his books, leading Cornwell into a stint as an MI5 intelligence officer in Germany — and later to a career as the novelist John Le Carré. Likewise, the novelist and naturalist Peter Matthiessen worked briefly for the Central Intelligence Agency after graduating from Yale.

But instances of naturalists using their work as a cover for espionage are scarce. Maybe that's because the people involved tend to be secretive. Or maybe it's because the naturalist connection has mainly served to advance a career, as in Le Carré's case, or to put a social and intellectual gloss on otherwise dirty work. The simple delights of birding were no doubt a relief from the double-dealing world of espionage for S. Dillon Ripley, who ran secret agents for the Office of Strategic Services, the C.I.A.'s predecessor agency, during World War II and later served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. It could also be a form of redemption (or not quite): James Schlesinger, for instance, served a brief, tumultuous tenure as head of the C.I.A., and a shill for Richard Nixon, in the aftermath of Watergate. When I chatted recently with Nicholas Dujmovic, a historian at the C.I.A., he remarked, "The only nice thing I've ever heard about Schlesinger is that he was a birdwatcher."

Dujmovic is the author of a recent article that reads a bit like a C.I.A. recruiting pamphlet for naturalists. It's about Stephen Maturin, the ship's surgeon in Patrick O'Brian's novels about the British Navy in the Napoleonic Wars. Maturin was "the kind of intelligence officer we need these days," according to Dujmovic: "A doctor by profession and a natural scientist by vocation, Maturin is well respected — and indeed publishes — in both fields, a situation that provides him with excellent cover for travel to exotic places and for establishing and maintaining contacts worldwide." The article goes on to list traits that make Maturin "the ideal intelligence officer" not just for his time, but for ours: He is discreet, skeptical, and ideological (though with a knack for deception and a willingness to bend certain principles for the cause). He's also comfortable working in a compartmentalized, need-to-know culture, and he is "like every intelligence officer at his core, a collector."

I'd add a couple of traits that might seem to make other naturalists excellent spies, too: They often spend years becoming invisible, or at least innocuous-seeming, to the animals they study, so they can observe them behaving naturally at close range. And they are adept at spotting nuances and subtle shifts that are often the first signs of coming upheaval.

But this suggests what may be a better idea. We no longer live, if we ever did, in a James Bond and Dr. Goldfinger world, or a world where Cold War ideologies shape our conflicts. Instead, our wars increasingly result from environmental distress — including deforestation, erosion, dwindling water supply, food shortages and the trade in conflict resources—not just blood diamonds but also timber and endangered wildlife. Different forms of environmental collapse have contributed to conflicts in Rwanda, Somalia, Darfur, Liberia, Afghanistan and Borneo, among others.

Naturalists doing field work are often the first to spot the developing maelstrom and raise the alarm. Unlike Baden Powell, they're the sort of people who actually do know one butterfly from another, and what the flapping of its wings may portend. Instead of trying to turn them into spies, wouldn't it be better for the people in power to listen to what they're already saying, and act as if it matters?

That way, we might not find ourselves engulfed in yet another ugly little war.

Clean Coal: Happy to Get My Hands Dirty on This One

Writing journalism often feels like shouting down a deep well. If you're lucky, now and then you hear an echo. But look what just came back up and spilling out the faucet. This video was based on an opinion piece I wrote in 2008 about the myth of clean coal. Sadly, the coal industry's spending seems to have paid off, in the utter failure of Congress to pass climate change legislation.

Here's the original essay, which appeared on Yale Environment 360:

You have to hand it to the folks at R&R Partners. They're the clever advertising agency that made its name luring legions of suckers to Las Vegas with an ad campaign built on the slogan "What happens here, stays here." But R&R has now topped itself with its current ad campaign pairing two of the least compatible words in the English language: "Clean Coal."

"Clean" is not a word that normally leaps to mind for a commodity some spoilsports associate with unsafe mines, mountaintop removal, acid rain, black lung, lung cancer, asthma, mercury contamination, and, of course, global warming. And yet the phrase "clean coal" now routinely turns up in political discourse, almost as if it were a reality.

The ads created by R&R tout coal as "an American resource." In one Vegas-inflected version, Kool and the Gang sing "Ya-HOO!" as an electric wire gets plugged into a lump of coal and the narrator intones: "It's the fuel that powers our way of life." ("Celebrate good times, come on!") A second ad predicts a future in which coal will generate power "with even lower emissions, including the capture and storage of CO2. It's a big challenge, but we've made a commitment, a commitment to clean."

Well, they've made a commitment to advertising, anyway. The campaign has been paid for by Americans for Balanced Energy Choices, which bills itself as the voice of "over 150,000 community leaders from all across the country." Among those leaders, according to ABEC's website, are an environmental consultant, an interior designer, and a "complimentary healer." Other, arguably louder, voices in the group include the world's biggest mining company (BHP Billiton), the biggest U.S. coal mining company (Peabody Energy), the biggest publicly owned U.S. electric utility (Duke Energy), and the biggest U.S. railroad (Union Pacific). ABEC — whose domain name is licensed to the Center for Energy and Economic Development, a coal-industry group — merged with CEED on April 17 to form the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE).

They're bankrolling the "Clean Coal" campaign to the tune of $35 million this year alone. That's a little less than the tobacco industry spent on a successful fight against antismoking legislation in 1998, and almost triple what health insurers paid for the "Harry and Louise" ads that helped kill health care reform in the early 1990s. In addition to the ads, the "Clean Coal" campaign has so far also sponsored two presidential election debates (where, critics noted, no questions about global warming got asked).

The urgent motive for an ad campaign this time is the possibility of federal global warming legislation. A cap-and-trade scheme for carbon dioxide emissions may come to a vote in the Senate this June. Coal is also struggling to overcome fierce resistance at the state and local level; Kansas, Florida, Idaho, and California have already effectively declared a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. Nationwide, 59 new coal-fired power plant projects died last year (of 151 proposed), mostly because local authorities refused to grant permits or because big banks withheld financing. Both groups are alarmed about the lack of practical remedies to deal with coal's massive CO2 emissions.

The coal industry is clearly alarmed, too, if only about its continued ability to do business as usual. In addition to the "Clean Coal" ad campaign, the industry's main lobbying group, the National Mining Association, increased its budget by 20 percent this year, to $19.7 million. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, individual coal companies will spend an additional $7 million on lobbying. Coal industry PACs and employees also routinely donate $2-3 million per election cycle in contests for federal office. Altogether, that adds up to a substantial commitment to advertising and lobbying.

And the commitment to clean? The scale of the problem suggests that it needs to be big. Coal-fired power plants generate about 50 percent of the electricity in the United States. In 2006, they also produced 2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide — 36 percent of total U.S. emissions. For a remedy, the industry was banking on a proposed pilot plant called FutureGen, which would have used coal gasification technology to separate out the carbon dioxide, allowing it to be pumped into underground storage. But in January, the federal government canceled that project because of runaway costs. At last count, FutureGen was budgeted at $1.8 billion — with about $400 million of that coming from corporate partners over ten years. That is, the "commitment to clean" would have cost roughly as much per year as the industry is now spending on lobbying and "Clean Coal" advertising.

The business logic of this spending pattern is clear: Promoting the illusion that coal is clean, or maybe could be, helps to justify building new coal-fired power plants now. The tactic is at times transparent: In Michigan recently, a utility didn't promise that a proposed $2 billion plant would have carbon-control technology — merely that it would set aside acreage for such technology. The proponents of a new power plant in Maine talked about capturing and storing 25 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions, but didn't say how, and even if they figure that out, the plant would still produce two million tons of CO2 annually.

Actually making coal clean would be hugely expensive. In this country, most research focuses on coal gasification, which aims to remove CO2 and other pollutants before combustion. But only two power plants using the technology have actually been built in the United States, in Indiana and Florida, and the purpose of both was to capture sulphur and other pollutants. Neither takes the next step of capturing and storing the CO2. They also manage to be online only 60 or 70 percent of the time, versus the 90-95 percent uptime required by the power industry. In Europe, researchers prefer post-combustion carbon capture. But the steam needed to recover CO2 from the smokestack kills the efficiency of a power plant.

Since neither technology can be retrofitted, both require the construction of new coal-fired power plants. So instead of reducing emissions, they add to the problem in the near term. And the question remains of what to do with the carbon dioxide once you've captured it. Industry has had plenty of experience with temporary underground storage of gases — and researchers say they are confident about their ability to sequester carbon dioxide permanently in deep saline aquifers. But utilities don't want to get stuck monitoring storage in perpetuity, or be liable if CO2 leaks back into the atmosphere. In any case, data from demonstration storage projects won't be available for at least five years, meaning it will be 2020 before the first plants using "carbon capture and storage" get built. If predictions from global warming scientists are correct, that may be too late.

A better strategy, argues Bruce Nilles, director of the Sierra Club's National Coal Campaign, is conservation, with a cap-and-trade system driving overall emissions down by two percent a year over the next 40 years. At the same time, he says, utilities need to increase their reliance on wind and solar power, supplemented by natural gas. Nilles thinks this may already be happening. In Colorado, Xcel Energy, which generates 59 percent of its power from coal, recently shelved a proposed 600-megawatt "clean coal" power plant; it's now seeking to develop 800 megawatts of new wind power by 2015.

Finally, industry and environmentalists together also need to figure out a funding mechanism for research to make "clean coal" something more than an advertising slogan. (One possibility being debated in Europe: Instead of giving away cap-and-trade emissions permits to industry, auction them off, with some of the revenue going to research.) Nilles is also holding out for a "clean coal" technology that can be retrofitted on existing plants.

But nobody expects coal to give up dirty habits easily. Some coal advocates are already trotting out one dire study by M. Harvey Brenner, a retired economist from Johns Hopkins University. It takes a hypothetical example in which higher-cost alternative energy sources replace 78 percent of the electricity now produced by coal — leading to lower wages, higher unemployment, and the death of 150,000 economically distressed Americans per year. (In another scenario described by Brenner, 350,000 Americans die annually because they did not show coal the love.) Only a spoilsport would add that the study was paid for by the coal industry and that the article appeared not in a peer-reviewed journal, but in a trade magazine. Someone from ACCCE is probably already on the phone. "BURN COAL OR DIE" is a little crude as an advertising slogan. But the clever folks at R&R Partners can no doubt polish it into something that will make "Harry and Louise" want to get up and dance.

February 19, 2011

The Species Seekers Quiz: Getting Batty

[image error]Who was Obed Bat?

1. A student of Linnaeus who became one of his "apostles" in the Far East.

2. Head of the scientific team aboard the British Navy corvette Challenger on the first great round-the-world oceanographic survey.

3. A naturalist who was a comic figure in American fiction.

4. A British ornithologist who was ritually beheaded as a spy.

And the answer is:

A fictional naturalist in a book.

In 1825, James Fenimore Cooper was working to complete the third novel in his Leatherstocking series, a sequel to his bestselling The Last of the Mohicans. For The Prairie, Cooper created a new character named Obed Bat, or as he liked to hear himself called, on the Latinate model of Carolus Linnaeus, Dr. Battius. It was a comic caricature of the naturalist "absently endangering himself and others in an addled quest for new species."

In 1825, James Fenimore Cooper was working to complete the third novel in his Leatherstocking series, a sequel to his bestselling The Last of the Mohicans. For The Prairie, Cooper created a new character named Obed Bat, or as he liked to hear himself called, on the Latinate model of Carolus Linnaeus, Dr. Battius. It was a comic caricature of the naturalist "absently endangering himself and others in an addled quest for new species."

Constantine Rafinesque

Cooper probably modeled Bat on Constantine Rafinesque, who, according to Rafinesque scholar, Charles Boewe, described nine Kentucky bats, along with many other mammals, including the prairie dog.

February 17, 2011

The Species Seekers Quiz: Edgar Allan Poe's Only Bestseller?

What was Edgar Allan Poe's only bestseller during his lifetime?

Authors can look gloomy when books don't sell.

1. The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, a sea adventure and his only novel.

2. The Conchologist's First Book, a textbook.

3. The Balloon Hoax, an account of an astounding trans-Atlantic balloon trip.

4. Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, a collection of his stories, in which "terror has been the thesis."

And the answer is[image error]

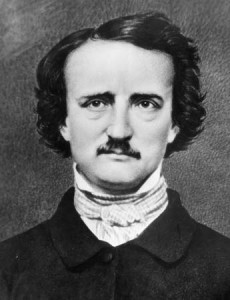

The Conchologist's First Book: Or a System of Testaceous Malacology was an illustrated school text published in 1839, 1840, and 1849. It was an adaptation of The Manual of Conchology written by English author and lecturer Thomas Wyatt.

For a fee of $50, Poe wrote the preface, translated some French text by naturalist Georges Cuvier, and edited and reorganized the book's accounts of animals and its taxonomy scheme. The Conchologist's First Book sold out within the first two months of publication, and was Poe's only work to go into a second edition in his lifetime.

He received no royalties.

Runner's High: It's Not the Endorphins

In today's New York Times, Gretchen Reynolds has a nice article arguing that runner's high doesn't actually come from endorphins. It seems we are more like potheads once removed:

In a groundbreaking 2003 experiment, scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology found that 50 minutes of hard running on a treadmill or riding a stationary bicycle significantly increased blood levels of endocannabinoid molecules in a group of college students. The endocannabinoid system was first mapped some years before that, when scientists set out to determine just how cannabis, a k a marijuana, acts upon the body. They found that a widespread group of receptors, clustered in the brain but also found elsewhere in the body, allow the active ingredient in marijuana to bind to the nervous system and set off reactions that reduce pain and anxiety and produce a floaty, free-form sense of well-being. Even more intriguing, the researchers found that with the right stimuli, the body creates its own cannabinoids (the endocannabinoids). These cannabinoids are composed of molecules known as lipids, which are small enough to cross the blood-brain barrier, so cannabinoids found in the blood after exercise could be affecting the brain.

You can read the whole story here.

February 16, 2011

Great Species Seekers: William Doherty

The Cincinnati-bred lepidopterist William Doherty worked in the Indo-Pacific in the 1880s and 90s, and was frequently vexed with tropical afflictions. He wrote home that he couldn't keep his specimen pins from rusting in the rainy season. "Salt and sugar here liquefy every night and have to be dried over the fire every day," he added, "and the boots I take off at night are sometimes covered with mould in the morning."

Doherty was generally too busy to dwell on his misfortunes. He once summed up a year's work in the Indo-Pacific islands in telegraphese, sounding a bit like Fearless Fosdick, the comic book hero who could describe it as "merely a flesh wound" even when machine gun bullets made his midsection look like Swiss cheese: "Loss of all my collections, money, journals and scientific notes at Surabaya in Java. Proceed by way of Macassar to the island of Sumba. Dangerous journey in the interior. Discovery of an inland forest region, and[image error] many new species of Lepidoptera. King Tunggu, human sacrifices, strange currency …. Visit to the Smeru country. Hunted by a tiger when moth-catching. Hunt tigers myself. Leave for Borneo. Ascent of the Martapura River from Banjermasin. Life among the Dyaks in the Pengaron country. Head-hunting. The orang-utan."

The real peril, as for many species seekers, was disease, a less colorful but more efficient killer. In a letter sent from Kenya in February 1901, William Doherty was characteristically dismissive about what he called "the usual adventures. The first were with lions and rhinos. Lately it has been with wild buffalo, a rogue elephant, and a leopard who comes in our boma [a corral or enclosure] every night. … Only the other night I had to fight for my life with the marauding Masai."

About that time, a friend sent a note to Doherty from England. It came back a few months later stamped "decede deceased." The cause, it turned out, was dysentery.

February 15, 2011

The Species Seekers Quiz: Mark Twain's Mighty …????

On what river did young Samuel Clemens (later Mark Twain) hope to make his reputation when he lit out from home in 1857?

On what river did young Samuel Clemens (later Mark Twain) hope to make his reputation when he lit out from home in 1857?

1. The Mississippi

2. The Ohio

3. The Congo

4. The Amazon

And the answer is

[image error]

Other oxbows, other river pilots

The Amazon. In the mid-19th century, almost everyone dreamed of going out into the far corners of the world and discovering amazing new species. While working as a printer's apprentice, Clemens read an account of Amazonian exploration and became "fired with a longing to ascend" the river. He found a fifty dollar bill in the street and took off for this "romantic land where all the birds and animals were of the museum varieties." He traveled down the Ohio River and the Mississippi to New Orleans to embark on a ship to Pará, Brazil, at the mouth of the Amazon. His hopes were dashed, however, when he found that there was no ship leaving for Pará and never had been. So he learned to make do with the river at hand.

(Read more about how the search for species changed our world in The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth by Richard Conniff.)

Everybody's a Little Bit Racist (and Some a Little More So)

The other day in The New York Times I wrote a piece about how scientific racism poisoned the career of an explorer named Paul Du Chaillu. Some of the reader comments make it clear that we have not gotten over the urge to classify people by race, or the assumption among some white Europeans that they are innately superior.

Maybe that's because we are built, as social primates, to see the world in terms of in-groups and out-groups, us and them. It's how we became so successful as a species. As the song in "Avenue Q" puts it, we're all a little bit racist, or sexist, or otherwise prone to put people in pigeon holes and treat them differently because of it. But we also have an extraordinary ability to shift our in-group loyalties, to stop categorizing people as members of another race or gender or sexual orientation and align with them instead as fellow Giants fans, or IBM workers, or ballroom dancing nitwits (oop, sorry, out-group prejudice slipping in).

The problem comes when people in power persist in using categories to keep other people down. I was once interviewing a professor at a prestigious university, who volunteered that he tries to hire only Mormons. You could tell from the way he said it that he thought it was harmless. He was a Mormon, and he had this idea that Mormons work harder. In-group loyalty rather than out-group prejudice seemed to be his motive, the way a black musician or an Irish cop (double stereotype alert!) might hire fellow blacks or Irish for some equivalent reason. But he was hiring them to work on a problem that disproportionately affects blacks and Hispanics. So it was all around kind of dumb, not to mention illegal.

More recently, I ran into another university professor who tried to put an intellectual gloss on his bigotry. He'd started reading my book The Species Seekers, and he wrote to tell me how much he was enjoying it. I suggested that he put up a review on Amazon, and he did, calling it "a page-turner suitable for professionals as well as those with a more casual interest in biology and quirky biologists. It would make, with qualifications, fine supplemental reading for the history and philosophy of biology course that I teach." But then he got to the part in the book about nineteenth-century scientific racism and he added:

The greatest weakness of the book is the highly politically correct but genetically incorrect view that there is no scientific basis to race. Look at an NBA team, the running backs in the NFL, the defensive lineup (speed) as compared to the offense, and the list of Nobel Prize winners. There are none so blind as those who will not see. And the peer-reviewed literature reports differences in brain sizes and many other characteristics. On the other hand, who dares to attempt free speech in 2010?

Tell me if I am misreading this: NBA players are mostly black, Nobel Prize winners mostly white. And that's the result of racial differences, not culture? It's because blacks have strong legs and whites have big brains? And by blacks, he means stocky West Africans as well as stringy Ethiopians (sorry, more stereotypes), not to mention Bushmen, Bakola, and Bakonjo?

I can agree with him about at least one thing: "There are none so blind as those who will not see."

Scientific racism lives.