Richard Conniff's Blog, page 107

April 21, 2011

When Rich Folk Tuck a Species in their Well-Lined Pockets

Walter Rothschild and tortoise at Tring

The (U.K.) Guardian reports that billionaire Richard Branson wants to create a refuge for ring-tailed lemurs in the Caribbean, because continuing deforestation threatens survival of these colorful primates in their native Madagascar.

There are plenty of historical precedents for what Branson is proposing. Two of them turn up in my book, The Species Seekers. Both involved British plutocrats. One turned out to be irrelevant to conservation of the species, while the other was a life-saver.

But let's start with what Branson has in mind:

"We have had a lemur project in Madagascar the past few years and seen that things are getting worse for them so we thought about finding a safe haven," he told the Guardian. "We brought in experts from South Africa to Moskito island and they said it would be perfect."

But other experts say the introduction of an alien species from 8,000 miles away could harm the lemurs and local wildlife.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature's species survival commission told the BBC the project could contravene its code for translocations and said the harm from introducing species outweighed benefits.

Other experts said it was too soon to judge. "It could be a brilliant or terrible idea but we just don't know yet," said Penelope Bodry-Sanders, the founder of Lemur Conservation Foundation, a Florida-based group which has a sister reserve in Madagascar.

"We don't know what pathogens the lemurs will bring to the Caribbean or what pathogens they will receive. It is great that Mr Branson cares, and he has a history of acting responsibly, but we need more information. The jury is out on this."

Walter Rothschild, an eccentric member of the banking family, had much the same idea early in the twentieth century:

At one point, recognizing that within the previous five years, visiting ships had taken and eaten 80 percent of the giant tortoise species on Duncan Island (now Isla Pinzon) in the Galapagos, he ordered his team to remove all 29 survivors "to save them for science" back at Tring, his family's country house outside London. Rothschild meant to keep them alive, along with 30 giant tortoises from other Galapagos islands. "I think 60 living Galapagos tortoises will make people stare," he wrote. This was no doubt especially true when Rothschild, in top hat and tails, rode on a tortoise's back, in the photo above.

But Walter's megalomaniacal rescue attempt ultimately made no difference to survival of the species. Enough tortoises survived in the wild to provide the stock for a later, more scientific, captive-rearing program, begun in 1965, with the result that roughly 350 tortoises now live on Pinzon. Rothschild's conservation efforts were more successful when he leased entire islands to protect wildlife on site–notably on Aldabra in the Indian Ocean.

Things turned out much better, though, when wealthy Europeans essentially kidnapped Père David's deer:

David first heard about the species that would become known as Père David's deer, or Elaphurus davidianus, soon after his arrival in China. It had long since been hunted out in the wild, but a herd of 120 animals survived in a deforested and overgrazed imperial hunting park a few miles south of Beijing. Locals called this deer ssu-pu-hsiang, "the four characters which do not match," because it supposedly had the tail of an ass, the hooves of a cow, the neck of a camel, and the antlers of a stag. David made the hike out to the imperial park and by befriending the guards or climbing on a wall he managed to get a glimpse of the herd. "All my attempts to secure a specimen, or even some remains, were unsuccessful," he wrote. "It is said that there is a death penalty for anyone who dares to kill one of these animals." But his sense of the "utmost importance" of each species—each "dot" or "comma" in the grammar of nature—made him persist, and in January 1866 he somehow got hold of two skins "in fairly good condition."

In the ensuing excitement about the "new" species, both French and British diplomats pressed the superintendent of the imperial estates—probably none too gently–to release live animals for shipment back to Europe. From these animals, a breeding population eventually became established at Woburn Abbey, the Duke of Bedford's estate north of London. In China meanwhile, soldiers in the Boxer Uprising of 1900 bivouacked on the old imperial hunting grounds, where they shot and ate the last remaining deer.

Père David's deer would thus have become one more species lost in the rush to a landscape of pigs and potatoes, except that it had flourished in captivity outside China. In 1985, Woburn Abbey shipped a breeding population back to Beijing, where the deer soon became established on the grounds of the same imperial park where Armand David first discovered them, now called the Beijing Milu Park ("milu" being the modern Chinese name for the species). The deer population rapidly expanded, as deer populations will do, and they have since been translocated to multiple protected areas around China. Instead of being extinct, the species now numbers close to 1000 animals in their native habitat.

The bottom line? Branson and the world at large ought to focus on saving Madagascar, one of the most diverse environments on Earth, and on stopping short-sighted politicians from turning the island into just another landscape of pigs, potatoes, and, of course, rice. That's the real fight. The value of charismatic species like the ring-tailed lemur is that they serve as the poster children for preserving entire environments. They motivate people to protect habitats shared with thousands of other species that are less charismatic, but are no less precious.

If Madagascar goes, it will no doubt be beneficial that the ring-tailed lemur has survived, and we will be grateful to Branson for his efforts.

But it will be like saving the cover of one of the world's great books, and letting the book itself burn.

April 18, 2011

Darwinizing Before Darwin

The original Darwinizer

Before Charles Darwin was even born,the word "darwinizing" was already a pejorative, in some circles. Samuel Taylor Coleridge used it to disparage the abstruse theorizing of Darwin's grandfather Erasmus. Today is the anniversary of Erasmus Darwin's death in 1802 and to mark the occasion, here's how I describe him in The Species Seekers:

As the industrial revolution gathered force, new mines, quarries, and canals sliced open the countryside, exposing past geological ages. Erasmus Darwin, son of Robert and grandfather of Charles, visited one such excavation near Nottingham in 1767 to observe "the Goddess of Minerals naked, as she lay on her inmost bowers," with belemnites, ammonites, and "numerous other petrified shells" wantonly strewn across the fresh-cut banks.

Darwin, a physician, poet, and philosopher, was a likable figure–fat, florid, pockmarked, with a ready smile and a voluptuary's heart. (How else could he have turned a canal excavation into a naked Goddess?) He loved food, and, in a cockeyed foreshadowing of his grandson's ideas about natural selection, his favorite nostrum for patients was "Eat or be eaten." He had a deep faith in human progress (not least in his own family). The sight of fossil shells and other primitive creatures recovered from oblivion made him think about progress in the natural world, too. Years later, in his 1794 book Zoonomia, he would venture the "transmutationist" idea that over the course of "perhaps millions of ages … all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament," with successive generations acquiring new traits and passing down improvements to posterity. But for the moment, he expressed his belief in the common descent of species more simply, by having a motto painted like a bumper sticker on his carriage door: "E conchis omnia" ("Everything from shells").

Even that smacked of heresy, to some. A local clergyman mocked Darwin in verse: "Great wizard he! by magic spells/ Can all things raise from cockle shells." Long before Charles Darwin was born, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge coined the term "darwinizing" to mock this sort of evolutionary theorizing. Fear of offending patients soon caused Erasmus Darwin to display his new motto only on his bookplate, rather than in the high street.

April 14, 2011

D.H. Lawrence on Jabbing, Terrifying Monsters

The hummingbirds are just starting to migrate back to New England. You can read about their fierce, frantic lives in my book Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time. And while you are waiting for your copy to arrive, this perfect, unsentimental poem by D.H. Lawrence seems like the right way to celebrate:

Humming Bird

I can imagine, in some otherworld

Primeval-dumb, far back

In that most awful stillness, that only gasped and hummed,

Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

Before anything had a soul,

While life was a heave of Matter, half inanimate,

This little bit chipped off in brilliance

And went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems.

I believe there were no flowers, then,

In the world where the humming-bird flashed ahead of creation.

I believe he pierced the slow vegetable veins with his long beak.

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the long telescope of Time,

Luckily for us.

April 13, 2011

Exploring Tropical Nature Before It Vanished Forever

Twenty years ago this past January, I went to Ecuador to travel with a team of amazing biologists working in Conservation International's Rapid Assessment Program. I wrote about the experience in Smithsonian Magazine, and later in a book, Every Creeping Thing (Henry Holt). Now CI has published its own book marking the 20th anniversary of the program, Still Counting. Longtime CI president Russ Mittermeier recalls how it all began:

RAP founders Gentry, Parker, Emmons, and Foster

Back in early 1990, my good friend, ornithologist Ted Parker, came into my office and in his inimitable way told me that he had an offer that I couldn't refuse. Although only in his late 30s at the time, Ted was already acknowledged as the greatest field ornithologist that had ever lived. He had the entire vocal repertoires of more than 4,000 bird species embedded in his brain; he had even discovered a species new to science simply by hearing it calling in the forest. He was charming, persistent, and endlessly enthusiastic about his passion for birds and conservation.

What Ted told me on that day was that he had been on an expedition to Bolivia, together with Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann, another avid bird-watcher, and Spencer Beebe, formerly of The Nature Conservancy and one of the co-founders of CI along with Peter Seligmann. They had been sitting around a campfire talking about how little we knew of the tropics and how we needed to learn more as quickly as possible, while there was still time. They had hit upon the idea of using a handful of superstar field biologists to go into remote areas and carry out "quick and dirty" assessments, using their amazing skills to do in a few weeks time what it would take ordinary field biologists months or years to do. Aside from Ted, there were only a few people around with such expertise in other groups of organisms such as plants, mammals, and reptiles, but there were enough of them to constitute a small team. Ted, Murray, and Spencer came up with the idea for the Rapid Assessment Program, or RAP, and Ted wanted to see if the young CI, only three years old, was interested in taking on this challenge.

We quickly put together a proposal and sent it to the MacArthur Foundation — which had shown a strong interest in biodiversity conservation — and had RAP funded within a few months time. Ted pulled together the initial team, which consisted of botanist Al Gentry from the Missouri Botanical Garden, plant ecologist Robin Foster from The Field Museum, and mammalogist Louise Emmons from the Smithsonian. Like Ted, Al was a genius. I remember once visiting him in his office and handing him a stack of unidentified plant specimens pressed in newspaper and fresh from the field. He leafed through them like the pages of a book, unhesitatingly identifying each one in a matter of seconds. He once got lost in a forest in Colombia for three or four days, crawled back into camp on the verge of starvation, grabbed some food from a pot cooking on the campfire, and went right back into the forest to collect a plant specimen that he thought was new to science. Robin and Louise had equally amazing expertise in their fields.

Our first RAP expedition was to Bolivia's Madidi region. It ran from May to June 1990 and produced amazing results: 403 bird species — nine of which were new for Bolivia — and high plant diversity (204 species in 0.1 hectare). The then president of Bolivia, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, was so taken with our RAP report that in 1995 he declared Madidi as a 1.8 million-hectare (almost 4.5 million-acre) national park, one of the largest parks then in existence. This political success demonstrated very clearly to us that RAP was not just going to be an important scientific tool. Everyone from decision-makers to the general public was taken with the program, and this demonstrated very quickly to us that the impact of RAP was going to exceed all of our original expectations.

At first, RAP focused exclusively on tropical rain forest regions, mainly in Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, the heartland of the Tropical Andes Hotspot and the most diverse tropical forest region on Earth. In 1994, with the participation of Bruce Beehler, the world's foremost expert on the birds of New Guinea, we began work in Papua New Guinea, an incredibly rich region even less well-known than South America. In 1997, RAP made its first foray into Africa with an expedition to Madagascar, and in 1998, a trip to Cote d'Ivoire in West Africa.

A new species of smoky honeyeater discovered on a RAP expedition to the Foja Mountains of Indonesia's Papua province.

A new species of smoky honeyeater discovered on a RAP expedition to the Foja Mountains of Indonesia's Papua province.After six years of work in the terrestrial realm, we decided to look into freshwater systems as well, a new dimension which we called AquaRAP. The first expedition was to the Rio Orthon in Bolivia in 1996, soon followed by trips to other important rivers in South America and to the Okavango Delta of Botswana. It was a logical next step to add MarineRAP, which began in 1997 with an expedition to Milne Bay Province in Papua New Guinea, followed by other expeditions to the Coral Triangle region of the Pacific.

These early marine expeditions had a huge impact, not just on CI's program but on conservation at a global level. Milne Bay became our major focus in Papua New Guinea, our expeditions to the Philippines and Sulawesi laid the groundwork for our Sulu-Sulawesi Seascape Program, and, most impressive of all, our 2001 expeditions to the Raja Ampat Islands of Papua Province in Indonesian New Guinea discovered the richest coral reef system known to date. This expedition resulted in the creation of 1.7 million hectares (4.2 million acres) of new marine protected areas in what we are now calling the Bird's Head Seascape.

By the end of the 1990s, RAP had developed a methodology that had been replicated by a number of other institutions. What's more, since we knew that RAP would have to be fully-owned by the countries where so much of the world's biodiversity resides, we began early on to train field biologists from these countries so that they could become the superstars of the future. Now, the vast majority of RAP work is done by researchers from the tropical countries themselves.

Sadly, the work of RAP has come at a high cost. When we began the program in 1990, we all knew that there were great risks involved. Reaching remote areas required travelling by small plane, helicopter, or boat in often precarious conditions, and the risks of disease, snakebite, guerrillas, and drug dealers were ever-present. We all took them for granted, and still do — an accepted occupational hazard. But the risks are real, as became painfully evident in August 1993, when two of our RAP founders, and perhaps the two greatest field biologists that ever lived — Ted Parker and Al Gentry — died in a plane crash in the mountains outside of Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Six years later, disaster struck again, this time during an AquaRAP expedition on Peru's Rio Pastaza. The expedition boat was trawling for fish when it got stuck on a submerged log, dragging the boat under water. Two people perished in this accident — Fonchi Chang, a promising young Peruvian ichthyologist, and Reynaldo Sandoval, a local boat driver. We were all shocked and greatly saddened by the loss of our friends and collaborators, but we never thought of ending the program because of them. Rather, we always felt that the best thing that we could do to honor the memory of these committed pioneers who gave their lives for conservation was to strengthen our resolve to continue the work that had been such an integral part of their lives.

Now, as I look back at the past 20 years, I am extremely proud of what RAP has accomplished. We have carried out an amazing 80 expeditions, discovered more than 1,300 species previously unknown to science and gathered vast amounts of data on poorly known species. The new protected areas created as a result of RAP expeditions have been of global significance, leading to major global programs extending far beyond CI's own activities. In several cases, our expeditions have laid the foundation for land claims by indigenous people, resulting in the creation of special community conservation areas. And perhaps most important of all, by training hundreds of students from the tropical countries, we have truly laid the groundwork for the future and created constituencies that are already carrying the cause of conservation forward.

But in spite of all that we have learned, there is still much to do. The pressures on biodiversity have not diminished, and many regions still remain unexplored. Knowledge has already helped to conserve some of the world's highest priority sites, and it will continue to be our strongest tool in ensuring the future of life on our planet. RAP has been critical in providing us with such knowledge, and we look forward to the next 20 years and the many challenges and the exciting new discoveries that lie ahead.

March 15, 2011

Walking with Rhinos

I arrived this morning in South Africa, where the newspapers are reporting that 71 rhinos–and nine poachers–have been killed this year here. That's on track with last year's very bad total of 333 rhinos killed in South Africa, all for the mythical medicinal powers of the rhino's horn. I'll be traveling around this week learning what wildlife authorities are trying to do about it.

I arrived this morning in South Africa, where the newspapers are reporting that 71 rhinos–and nine poachers–have been killed this year here. That's on track with last year's very bad total of 333 rhinos killed in South Africa, all for the mythical medicinal powers of the rhino's horn. I'll be traveling around this week learning what wildlife authorities are trying to do about it.

March 8, 2011

My Favorite Science Headline of the Week

From the folks at Science Daily comes a story headlined "Great Tits Also Have Age-Related Defects."

Yes, it's about the birds.

Great Tit Parus major (Credit: iStockphoto/Andrew Howe)

Specifically, Parus major, a songbird common in Europe.

That includes England, where "titting about" means wasting time, and "ta-ta" means "goodbye." Such a disappointment.

But "tit" also means breast, and the scientific name of this species means "larger breast." I have no clue why it got this name, or why our American species Baeolophus bicolor is named the titmouse. Neither looks like D-cup material. More informed readers can perhaps advise?

But enough adolescent sniggering. On to the science, which is what you're here for, right? It's based on the work of evolutionary biologist Sarah Bouwhuis:

Although great tits can live for nine years, breeding success declines rapidly after the age of two. Nevertheless, older great tits keep on breeding every year, says Bouwhuis: 'They carry on to the bitter end'. What is remarkable is that at the start of the breeding period there's very little difference between the nests of older and younger females. Bouwhuis discovered, however, that massive mortality occurs just after the young leave the nest. 'The parents still have to guide their young in the first crucial weeks after leaving the nest. Perhaps the older mothers have more trouble with that guidance; their young often fall prey to sparrowhawks, for example. Or maybe the older mothers have only been able to find less suitable places in the woods.'

March 7, 2011

Luddites as Fashion Victims

You just can't include every interesting fact or anecdote in a story. So I left this one out when I wrote in the current Smithsonian Magazine about the birth of the Luddite movement 200 years ago this week:

The machines the original Luddites smashed were "stocking frames" –that is, looms for making stockings. It was a thriving business early in the nineteenth century, because men need stockings to wear with their knee breeches.

Then along came that great fashion-maker Beau Brummell, popularizing the idea of full-length pants.

The stocking business sagged, and the loss of business imperiled the jobs of struggling loom stocking frame operators, who ultimately began to riot. Thus the original Luddites were fashion victims.

This hilarious note from Ian Kelly's Beau Brummel: The Ultimate Man of Style may help explain why the new style of pants suddenly became so popular:

One Persian ambassador to the Court of St. James's was moved to write that he found the Brummell style of trousers "immodest and unflattering to the figure … [they] look just like underdrawers–could they be designed to appeal to the ladies?" A more sympathetic or aroused observer noted that they were "extremely handsome and very fit to expose a muscular thigh," and society hostesses were later said to regret the passing of the fashion because "one could always tell what a young man was thinking."

New Petrel Hiding in Plain Sight

People have this notion that there's nothing left to discover, other than a bunch of obscure insects. So it's lovely when a big, spectacular new species turns up hiding in plain sight That's what just happened within sight of crowded beaches in Chile, according to a report in the Los Angeles Times. Noted ornithologist Peter Harrison caught the new species on camera:

People have this notion that there's nothing left to discover, other than a bunch of obscure insects. So it's lovely when a big, spectacular new species turns up hiding in plain sight That's what just happened within sight of crowded beaches in Chile, according to a report in the Los Angeles Times. Noted ornithologist Peter Harrison caught the new species on camera:

"This is the first new species of storm petrel discovered in 89 years, and the first new species of seabird discovered in 55 years –- and if we had won the lottery we could not feel better," Harrison said in an interview

"We believe this is a relic population that was completely missed by Darwin himself, who sailed along that very coast a century ago," Harrison said.

"And guess what? There are thousands of them in that area, which is plied by cruise ships, cargo vessels and fishing boats, all within sight of crowded beaches."

Researchers at the University of Chile in Santiago are analyzing collected blood samples and feathers to learn more about the birds, where they breed and if they migrate to wintering grounds elsewhere.

"Important discoveries usually happen in remote places like Borneo or the Amazon forests," said Garry George, chapter network director for Audubon California.

"Not this time," he said. "This bird has been under everyone's noses in a popular area for decades."

March 6, 2011

Tough Love for Bambi?

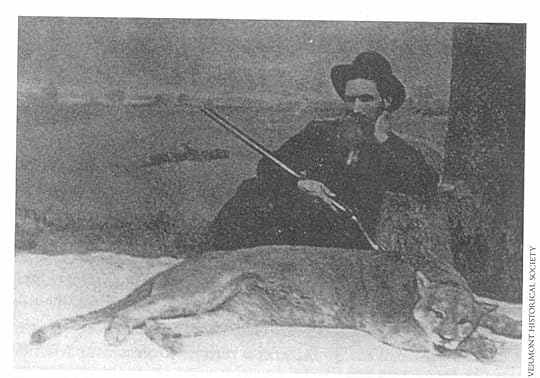

The last eastern cougar shot in the state of Vermont

A week or two back, when the snow was a foot deep and food was scarce, I had 18 white tail deer in my yard on the Connecticut coast. So what's the answer to deer overpopulation in the U.S. Northeast?

Sorry, it's now officially extinct. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has just removed the eastern cougar from its endangered species list, says Mark McCullough, a biologist there, because years of searching have turned up no evidence of its survival:

A breeding population of eastern cougars would almost certainly have left evidence of its existence, he said. Cats would have been hit by cars or caught in traps, left tracks in the snow or turned up on any of the hundreds of thousands of trail cameras that dot Eastern forests.

But researchers have come up empty.

The private Eastern Cougar Foundation, for example, spent a decade looking for evidence. Finding none, it changed its name to the Cougar Rewilding Foundation last year and shifted its focus from confirming sightings to advocating for the restoration of the big cat to its pre-colonial habitat. The wildlife service said it has no authority under the Endangered Species Act to reintroduce the mountain lion to the East.

The promising news is that the eastern cougar may actually be genetically identical to its western siblings, and they are rapidly expanding their range back eastward. If it happens, that could make running in the woods a lot more interesting for the deer (and maybe for us, too) and it might help restore a more natural balance of species. It may sound a little tough on poor Bambi. But scientific evidence demonstrates that species–and entire ecosystems–are better off when top predators are around to do their regrettable business.

The last eastern cougar shot in the state of Vermont

A w...

The last eastern cougar shot in the state of Vermont

A week or two back, when the snow was a foot deep and food was scarce, I had 18 white tail deer in my yard on the Connecticut coast. So what's the answer to deer overpopulation in the U.S. Northeast?

Sorry, it's now officially extinct. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has just removed the eastern cougar from its endangered species list, says Mark McCullough, a biologist there, because years of searching have turned up no evidence of its survival:

A breeding population of eastern cougars would almost certainly have left evidence of its existence, he said. Cats would have been hit by cars or caught in traps, left tracks in the snow or turned up on any of the hundreds of thousands of trail cameras that dot Eastern forests.

But researchers have come up empty.

The private Eastern Cougar Foundation, for example, spent a decade looking for evidence. Finding none, it changed its name to the Cougar Rewilding Foundation last year and shifted its focus from confirming sightings to advocating for the restoration of the big cat to its pre-colonial habitat. The wildlife service said it has no authority under the Endangered Species Act to reintroduce the mountain lion to the East.

The promising news is that the eastern cougar may actually be genetically identical to its western siblings, and they are rapidly expanding their range back eastward. If it happens, that could make running in the woods a lot more interesting for the deer (and maybe for us, too) and it might help restore a more natural balance of species.