Richard Conniff's Blog, page 104

June 30, 2011

Financial Lessons from Nature: A Follow-Up.

For some reason, a lot of visitors to this site seem to be checking out my NPR commentary that aired on November 18, 2008, about lessons learned from the natural world for dealing with the financial crisis. Here was my key piece of advice:

I saw forest fire ravage Yellowstone in 1988. It looked like the end of the world then, too. But when I went back a few years later, the blackened areas were flourishing with new growth. The same thing happens when financial markets go up in flames. Buck up your courage, buy some stock, and the grass can be green again for us, too.

So, to quote Sarah Palin, how's that workin' out for ya?

Next day the Dow-Jones Industrial Average closed at 7997. If you had suddenly realized–Eureka!–that Mother Nature is the master investor and put all your money into an index fund that day, you would now be up better than 60 percent. (The Dow closed yesterday at 12,261.)

So did I follow my own advice? A little. I invested some of my retirement funds around then, and it has paid off. Unfortunately, I have no clue what Mother Nature says about when to sell.

June 27, 2011

Why Shyness and Introversion are Normal

Pumpkinseed sunfish: Better shy or sunny? (Image by jeffcurrier.com)

In her New York Times article about our tendency to regard shyness and introversion as diseases, to be treated with antidepressants, writer Susan Cain takes some examples form the natural world:

We even find "introverts" in the animal kingdom, where 15 percent to 20 percent of many species are watchful, slow-to-warm-up types who stick to the sidelines (sometimes called "sitters") while the other 80 percent are "rovers" who sally forth without paying much attention to their surroundings. Sitters and rovers favor different survival strategies, which could be summed up as the sitter's "Look before you leap" versus the rover's inclination to "Just do it!" Each strategy reaps different rewards.

IN an illustrative experiment, David Sloan Wilson, a Binghamton evolutionary biologist, dropped metal traps into a pond of pumpkinseed sunfish. The "rover" fish couldn't help but investigate — and were immediately caught. But the "sitter" fish stayed back, making it impossible for Professor Wilson to capture them. Had Professor Wilson's traps posed a real threat, only the sitters would have survived. But had the sitters taken Zoloft and become more like bold rovers, the entire family of pumpkinseed sunfish would have been wiped out. "Anxiety" about the trap saved the fishes' lives.

Next, Professor Wilson used fishing nets to catch both types of fish; when he carried them back to his lab, he noted that the rovers quickly acclimated to their new environment and started eating a full five days earlier than their sitter brethren. In this situation, the rovers were the likely survivors. "There is no single best … [animal] personality," Professor Wilson concludes in his book, "Evolution for Everyone," "but rather a diversity of personalities maintained by natural selection."

The same might be said of humans, 15 percent to 20 percent of whom are also born with sitter-like temperaments that predispose them to shyness and introversion.

June 24, 2011

Listening to Alvin the Chipmunk as if Your Life Depends on it

It probably isn't too surprising that birds deciding where to nest actually listen for the sound of their major predators, and avoid those areas. But I am always interested in new examples of the ways one species eavesdrops on another. And I am genuinely surprised that chipmunks eat birds (ALVIN, how could you!). Finally, it seems curious that Texas Tech scientists would be doing field research in the Hudson River Valley, and publishing their results in a British journal.

How provincial of me:

Newswise — Ground-nesting birds face an uphill struggle to successfully rear their young, with many eggs and chicks falling prey to predators.

However, two researchers at Texas Tech University have found that some birds eavesdrop on their enemies, using this information to find safer spots to build their nests. The study – one of the first of its kind – was published this week in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Animal Ecology.

Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) and veeries (Catharus fuscescens) both build their nests on the ground, running the risk of losing eggs or chicks to neighboring chipmunks that prey on the birds.

Nesting birds use a range of cues to decide where to build their nests, but doctoral candidate Quinn Emmering and Kenneth Schmidt, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, wondered if the birds eavesdrop on the chips, chucks and trills chipmunks use to communicate with each other.

"Veeries and ovenbirds arrive annually from their tropical wintering grounds to temperate forests," Emmering said. "They must immediately choose where to nest. A safe neighborhood is paramount, as many nests fail due to predation. Predators are abundant. However, many predators communicate with one another using various calls, scent marks or visual displays that become publicly available for eavesdropping prey to exploit."

Working in the forested hills of the Hudson Valley 85 miles north of New York City, Emmering and Schmidt tested their theory that ovenbirds and veeries might be eavesdropping on chipmunks' calls before deciding where to nest. At 28 study plots, a triangular arrangement of three speakers played either chipmunk or grey tree frog calls (a procedural control), while at 16 "silent" control sites no recordings were played.

"Chipmunks call often during the day and sometimes join in large choruses," Emmering said. "We thought this might be a conspicuous cue that nesting birds could exploit."

The researchers found that the two species nested further away from plots where chipmunk calls were played. The size of the response was twice as high in ovenbirds, which nested 65 feet further away from chipmunk-playback sites than controls, while veeries nested only 32 feet further away.

The weaker response by veeries suggests they may not attend to chipmunk calls as ovenbirds do. This difference could ultimately have an effect on how their respective populations are able to respond to dramatic fluctuations in rodent numbers that closely follow the boom-to-bust cycles of masting oak trees.

"We found that by eavesdropping on chipmunk calls, the birds can identify hotspots of chipmunk activity on their breeding grounds, avoid these areas and nest instead in relatively chipmunk-free spots," Emmering said.

Veeries are forest thrushes with warm, rusty-colored backs and cream-colored, spotted chests. Ovenbirds are large warblers with dark streaks on their underside, and are olive above with a bold white eye-ring and an orange crown bordered by two dark stripes.

Ovenbirds and veeries primarily forage on the ground and the shrub layer of the forest. Veeries build open, cupped-shaped nests directly on the ground or up to 3 feet high in shrubs. Ovenbirds, on the other hand, always nest on the ground, building dome-shaped nests made of leaves, pine needles and thatch with a side entrance. Ovenbirds are so-called because their unique nests resemble a Dutch oven where they "cook" their eggs.

Chipmunks produce three types of calls: a high pitched "chip," a lower pitched "chuck" and a quieter "trill" consisting of multiple, twittery notes. Chips and chucks are often given in a series when a predator is detected and trills are usually in response to being chased.

Journal of Animal Ecology is published by Wiley-Blackwell for the British Ecological Society. Content lists are available at www.journalofanimalecology.org. The paper will be published on Friday (June 24).

A Source of Great Images from Natural History

The Biodiversity Heritage Library has put a collection of natural history prints online. I'm a sucker for the old ones. Check out their stuff on Flicker.

A citron breasted toucan from the Biodiversity Heritage Library

June 22, 2011

Great Natural History Reading

A while ago, the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment came up with a list of twelve classic nature and environment books. The ASLE is a professional organization of scholars, teachers, writers, and others focused on teaching literature from environmental perspectives. I'm not sure I agree with the list; it's entirely American, heavily Western, and surprisingly feminine for a topic long dominated, for better or worse, by male writers. I don't even recognize some of the titles they've listed, so I clearly need to do some reading. But people at the conference I'm attending have been talking about putting together a list of great natural history reading. So here's how ASLE approached the challenge, with teaching in mind:

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (1949) What can be said of Sand County Almanac? It is simply one of the great works of nature literature and from it has sprung the environmental movement. It was over 50 years ago that the book was first published, but his words and insights are as fresh as ever. Another Review Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Refuge by Terry Tempest Williams (1994) Refuge is a very different kind of nature writing. Williams visits to Utah's Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge are counterpoised against a far more personal theme: the slow death of her mother from cancer. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Land of Little Rain by Mary Hunter Austin, 1903. A series of poetic writings about the desert Southwestern desert, including observations about the flora, fauna, towns and Native American life. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey (1968) Edward Abbey is the undisputed the voice of the remote canyonland country of southern Utah and Northern Arizona. No book describes this harsh landscape better and with more hard-nose poignancy than Desert Solitare. More Extensive Review | Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko, 1977 This is a beautifully written, though complex, stream-of-consciousness, novel about a young Indian who returns to his New Mexico home after being imprisoned by Japanese during World War II. Deeply scarred by his war experiences, he seeks refuge on the reservation, but instead finds a world turned upside down with his father and best friend now dead. Racked by hopeless and despair, he eventually find his way by embracing his people's ancient ceremonies. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Walden by Henry David Thoreau (1862) In 1845, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American essayist and transcendentalist, gave Henry David Thoreau the use of a piece of property that he owned along Walden Pond near Concord, Massachusetts. On the Emerson property, Thoreau built a small cabin, planning to use it as a quiet place to finish work on a book that he was writing about a boat trip he and his brother had taken on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. But he had something else in mind, an experiment of sorts. Having lived with Emerson, and thoroughly steeped in transcendentalism, he wanted to see if he could apply transcendental principles to his life along the pond, working one day and spending the remaining six other days reading, contemplating and developing his consciousness. His expeniences gradually evolved into his most famous work Walden. ee More Extensive Review | Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard (1978) Annie Dillard's 20th century version of Walden: meditative, insightful, and edgy. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Practice of the Wild by Gary Snyder, 1990. A series of contemplative and insightful essays on the concept of wildness, nature, humanity and humility. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her by Susan Griffin, 1978. Griffin's early work of ecofeminism uses the structure of an epic poem to explore how male-dominated science, religion, and culture has conspired to subjugate women and nature. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Arctic Dreams Barry Lopez (1986) Barry Lopez (also the author of Of Wolves and Men) based this book on his years of experience in the Arctic. The book is vast in scope covering geography, weather, natural history, and anthropology. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962) Rachel Carson's Silent Spring is clearly one of the most important environmental books ever published. Using scientific research and persuasive logic, Carson warned of the consequences of careless use of pesticides. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich 1985. Gretel finds solace and a new life in Wyoming after the death of a friend, and in this small collection of essays, paints for us an engaging portrait of the rural west and its people: ranchers, sheepherders, cowboys, and Native Americans. Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase

Too Hot for Museums to Handle: Rhino Horns

This report comes from Rebecca Atkinson at Museums Journal:

Organised criminal gangs targeting museums as value of rhino horn soarsMuseums have been urged to remove all rhino horn from display amid fears that burglars are targeting museums in search of this valuable material.

The warning came after a rhino head was stolen in a burglary at Haslemere Educational Museum, Surrey, at the end of May.

The commercial value of rhino horn has soared recently largely because the Chinese market uses it in traditional medicines as a cure for cancer. It is also highly prized in Yemen, where it is used for dagger handles.

Detective constable Dave Pellatt of Surrey Police, who is investigating the crime, said the museum is believed to have been deliberately targeted. "There have been similar thefts reported elsewhere in Europe where the animal heads have later been found minus the horns, which have been sold on to be used in alternative medicines," he added.

Haslemere Museum has removed its remaining rhino heads from the premises following the theft, and its website states it will no longer store rhino material. The Horniman Museum in London has also removed all rhino horn from display until it can reassess its security arrangements.

Paolo Viscardi, the natural history curator at the Horniman Museum and a committee member at the Natural Science Collections Association (NatSCA), said there were rumours that some museums have raised the possibility of destroying rhino material in order to eliminate the risk of burglary.

The national parks in South Africa lock up rhino material rather than destroy it, and museums should do the same," he added. "Museums should also temporarily remove references to rhino horn collections from online collection databases as it makes it easy for these organised criminal gangs to find."

Viscardi believes that more thefts in the UK are inevitable: "The situation is likely to get worse before it gets better – at least no one has been hurt yet, but given the lengths to which poachers will go to in order to acquire rhino horn I expect it's just a matter of time."

Most museums in the UK hold some examples of rhino horn in their collections, from mounted heads to horn cups and dagger handles, but in the past these items have not necessarily required high levels of security.

NatSCA has produced some guidelines for museums concerned about rhino horn, which can be found on its website (www.natsca.info). It recommends that museums concerned about security levels should consider disposing of material either by loan or permanently to another museum willing to take it on.

June 21, 2011

Learning to Feel at Home

This week I'm at a conference at the North Cascades Institute, in northern Washington, about making natural history matter in the modern world. The sponsoring organization is the Natural History Network, and I've been struck by a few of things I've heard people say today.

My favorite, from Tom Fleischner, who teaches environmental studies at Prescott College in Arizona: "Natural history is the process of falling in love with the world. That's a very powerful thing. So much of environmental work tends to be based on fear rather than love."

We were talking about the ways we come to know the natural history of places, and Amanda Barney, a fisheries biologist from the University of Washingon, uttered this profound thought: "People learn more about where they go than where they're from."

In the same vein, Reed Noss of the University of Central Florida later said: "You have to know your place–the flora, the fauna, the watershed, the history of where you live, so you feel at home."

Carlos Martinez del Rio of the University of Wyoming uses isotopes to trace how an animal (himself included) has lived and he said roughly the same thing in a more personal way: "I am 85 percent Wyoming. I've analyzed my hair, fingernails, and skin, and I come from the land that I love."

One other thought: It's remarkable how much poetry comes up in the conversation of people who are scientists by profession. It reminds me of the quote from E.O. Wilson: "The ideal scientist thinks like a poet but works like a bookkeeper." The setting here is also suitable for poetry. I went for a walk this morning by a still lake with forested mountains leaping sharply up from the opposite shore, and beyond them, taller mountains still veined with snow, and with soft clouds wrapped like scarves around their peaks.

June 17, 2011

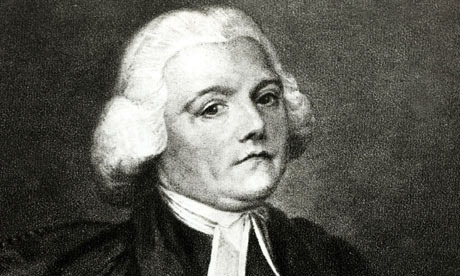

Happy Birthday, Gilbert White

White of Selborne

Today's the birthday of the great British naturalist Gilbert White (1720-1795), also known as White of Selborne, for his great book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, about the countryside around his home in the Hampshire village of Selborne.

I didn't have room for him in my book The Species Seekers, because White was more an observer than a discoverer of species.

But in her delightful 1982 book The Heyday of Natural History, journalist Lynn Barber gives a lovely account of his achievements:

"He was the first person to differentiate between the three species of 'willow wren' (the willow warbler, wood warbler and chiff-chaff); the first to describe the British harvest mouse and its nest; the first to observe that swifts copulate on the wing, that earthworms are hermaphroditic, and that male and female chaffinches form separate flocks in winter. He examined many birds' crops and droppings to discover their diet; he noted that owls hoot in B flat and cuckoos mainly in D; he shouted at bees through a loud-hailer to test their sense of hearing. He had a fine eye for ecological detail. He described how men riding over close turf are often followed by parties of swallows which seize the small insects thrown up by the horses' hooves; and how cattle, standing in a pond during hot weather, drop dung which nurtures insects 'and so supply food for the fish, which could be poorly subsisted but for this contingency.'"

My friend Fred Strebeigh has also written well about White, in a 1988 profile for Audubon Magazine:

Most important, White, in his book of letters, sounded human. Gone was the stuffiness of earlier naturalists. [Robert] Plot, for example, began his chapter on the animals of Oxford with embroidered fustian … White's readers, then, must have read with astonishment Selborne's first encounter with bird or beast–a story. For years, ravens had nested high in the jutting bulge of an ancient Selborne oak, the "Raven-tree." Generations of village youths had tried to reach the ravens' aerie, but none could clamber round the lower skirt of the bulge. "So the ravens built on," wrote White, "nest upon nest, in perfect security." Then came the day when the oak was sold, for twenty pounds, to build a bridge near London.

The saw was applied to the butt, the wedges were inserted to the opening, the woods echoed to the heavy blows of the beetle or mallet, the tree nodded to its fall; but still the [raven] dam sat on. At last, when it gave way, the bird was flung from her nest; and, though her parental affection deserved a better fate, was whipped down by the twigs, which brought her dead to the ground.

Here was the dawn of something new: natural history that watched closely and spoke with a human voice.

June 14, 2011

An Engrossing and Intriguing Read

A nice review for The Species Seekers just came in from the British magazine Real Travel. With apologies for the illegible pdf, what it says is that the book is "an engrossing and intriguing read that's sure to pique the interest of many a budding naturalist or historian in equal measure."

June 11, 2011

Making Species Matter with Colorful Names

Britain's The Guardian is running –a very curious contest–to give evocative "common" names to species now known only by their scientific names.

Last year, for instance, readers turned Megapenthes lugens into the Queen's executioner beetle, re-named Lucernariopsis cruxmelitensis as Mab's lantern beetle, and brought Arrhis phyllonyx to life as St John's jellyfish.

I like scientific names. Common, or local, names can vary from one town to the next. But scientific names allow people in different regions, and different countries, to know whether or not they are talking about the same species.

That said, British naturalist Richard Mabey, writing in , makes a nice case for the poetry of those local names.

I once had an amicable debate with the late John Fowles about the naming of nature. Behind his postmodern novelist's persona, Fowles was a skilled, fastidious and almost old-fashioned naturalist, who greatly preferred robust English tags to the "dark science" of Latin. He warmed to the walnut orb-weaver (a spider) but not Nuctenea umbratica. But he was flirting with Zen Buddhism at the time, one of whose axioms is that names are "a pane of smoked glass between us and reality". I disagreed. I've always felt that naming a plant or a creature is a fundamental gesture of respect towards its individuality, its distinction from the generalised green blur. It's the universal first step in beginning a relationship: "What's your name?" …

Writers may use common names imaginatively, but they rarely invent them. In that ongoing process we are all poets, and the immense lexicon of popular names for our fellow beings is the product of a communal enterprise that stretches back thousands of years. As well as Hernshaw, the heron has had more than 30 local names in Britain, including hegrie (Shetland), moll hern (Midlands), frank (from the bird's call – Suffolk), longie crane (Pembroke). Dandelion has at least 50, including clocks and watches, conquer more, devil's milk plant (from its white latex), four o'clock, golden suns, lion's teeth, piss-a-bed (the leaves are a renowned diuretic), priest's crown, wet-weed, wishes.

Common names are a kind of time capsule, a record of the powers of observation and literary inventiveness of ordinary people. They log resemblances, uses, sounds, mythic associations, smells, seasonal appearances, kids' games, superstitions, habitats. They're witty, concise, evocative, sometimes even satirical. The great champion and hedge-theorist of vernacular names was the 19th-century "peasant" poet John Clare …

Clare's respect for the authenticity of local language meant that he probably never made up a name himself. But in the heyday of natural history between the 18th and 19th centuries there was a frenzy of secular baptisms by clergymen, squires and every other kind of learned amateur with time on their hands. This was the period when many of our butterflies got their standard common names. Painted lady derived from the heavily made-up belles of the 18th century. Its wings have a warm flesh-tone and are tipped with mascara-like stripes. Red admiral (also the alderman) was coined because the patterning of its wings (patches plus stripes) resembles a naval flag.

Mother Shipton Moth

The common names of moths – there are more than 2,000 British species, few of which had any names at all before the 18th century – have been more functionally descriptive (but rarely dull), and often based on minute differential markings. The Hebrew character is named from a dark hieroglyph on its forewing. Mother Shipton carries the image of an old witch with a hooked nose on its wings. (The original, famously ugly Mother Shipton lived in a cave in Yorkshire.) The litany of moths whose caterpillars feed on species of willow (aka withy, sallies, saugh, popple, cat's-tails) reads like a found poem about sensual pleasure: angle shades, autumn green carpet, canary-shouldered thorn, coxcomb prominent, dark dagger, dingy mocha, engrailed, flounced chestnut, pale brinded beauty, ruddy highflyer …

Scientists quite rightly insist that universal Latin names (though these are unstable now) are essential if people from different cultures and languages are to understand each other. But it's in the common English names that the real richness and fascination lie. Here are wild organisms' hues, habits, habitats, histories, and humans' histories and curiosity, too. It's not stretching meanings to say that the vernacular lexicon is part of the ecosystem, a living and growing web which links us with all other species.