Richard Conniff's Blog, page 103

August 24, 2011

How Many, Noah? A Boatload.

Red throated barbet

For centuries scientists have pondered a central question: How many species exist on earth? Now, a group of researchers has offered an answer: 8.7 million. This article by Oxford University researcher Robert May explains why it matters.

And this report from Juliet Eilperin at the Washington Post explains the new study:

Although the number is still an estimate, it represents the most rigorous mathematical analysis yet of what we know – and do not know – about life on land and in the sea. The authors of the paper, published last evening by the scientific journal PLoS Biology, suggest 86 percent of all terrestrial species and 91 percent of all marine species have yet to be discovered, described, and catalogued.

The new analysis is significant not only because it gives more detail on a fundamental scientific mystery, but because it helps capture the complexity of a natural system that is in danger of losing species at an unprecedented rate.

Marine biologist Boris Worm of Canada's Dalhousie University, one of the paper's coauthors, compared the planet to a machine with 8.7 million parts, all of which perform a valuable function.

"If you think of the planet as a life support system for our species, you want to look at how complex that life support system is,'' Worm said. "We're tinkering with that machine because we're throwing out parts all the time.''

He noted that the International Union for Conservation of Nature produces the most sophisticated assessment of species on Earth, a third of which it estimates are in danger of extinction, but its survey monitors less than 1 percent of the world's species.

For more than 250 years scientists have classified species according to a system established by Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus, which orders forms of life in a pyramid of groupings that move from very broad – the animal kingdom – to specific species, such as the monarch butterfly.

Until now, estimates of the world's species ranged from 3 million to 100 million. Five academics from Dalhousie University refined the number by compiling taxonomic data for roughly 1.2 million known species and identifying numerical patterns. They saw that within the best-known groups, such as mammals, there was a predictable ratio of species to broader categories. They applied these numerical patterns to all five major kingdoms of life, which excludes micro-organisms and virus types.

The researchers predicted there are about 7.77 million species of animals, 298,000 plants, 611,000 fungi, 36,400 protozoa, and 27,500 chromists (which include various algae and water molds). Only a fraction of these species have been identified yet, including just 7 percent of fungi and 12 percent of animals, compared with 72 percent of plants.

"The numbers are astounding,'' said Jesse Ausubel, who is vice president of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and cofounder of the Census of Marine Life and the Encyclopedia of Life. "There are 2 .2 million ways of making a living in the ocean. There are half a million ways to be a mushroom. That's amazing to me.''

Angelika Brandt, a professor at the University of Hamburg's Zoological Museum who discovered multiple species in Antarctica, called the paper "very significant,'' adding that "they really try to find the gaps'' in current scientific knowledge.

Brandt, who has uncovered crustaceans and other creatures buried in the sea floor during three expeditions to Antarctica, said the study's estimate that 91 percent of marine species are still elusive matched her own experience of scientific discovery.

"That is exactly what we found in the Southern Ocean deep sea,'' Brandt said. "The Southern Ocean deep sea is almost untouched, biologically.''

One of the reasons so many species have yet to be catalogued is that describing and cataloguing them in the scientific literature is a painstaking process, and there are a dwindling number of professional taxonomists.

Seth Borenstein at Associated Press adds a few useful quotes.

While some scientists and others may question why we need to know the number of species, others say it's important.

There are potential benefits from these undiscovered species, which need to be found before they disappear from the planet, said famed Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson, who was not part of this study. Some of modern medicine comes from unusual plants and animals.

"We won't know the benefits to humanity (from these species), which potentially are enormous," the Pulitzer Prize-winning Wilson said. "If we're going to advance medical science, we need to know what's in the environment."

Of those species, 6.5 million would be on land and 2.2 million in the ocean, which is a priority for the scientists doing the work since they are part of the Census of Marine Life, an international group of scientists trying to record all the life in the ocean.

The research estimates that animals rule with 7.8 million species, followed by fungi with 611,000 and plants with just shy of 300,000 species.

While some new species like the strange mini-lobster are in exotic places such as undersea vents, "many of these species that remain to be discovered can be found literally in our own backyards," Mora said.

Outside scientists, such as Wilson and preeminent conservation biologist Stuart Pimm of Duke University, praised the study, although some said even the 8.8 million number may be too low.

The study said it could be off by about 1.3 million species, with the number somewhere between 7.5 million and 10.1 million. But evolutionary biologist Blair Hedges of Penn State University said he thinks the study is not good enough to be even that exact and could be wrong by millions.

Hedges knows firsthand about small species.

He found the world's smallest lizard, a half-inch long Caribbean gecko, while crawling on his hands and knees among dead leaves in the Dominican Republic in 2001. And three years ago in Barbados, he found the world's shortest snake, the 4-inch Caribbean threadsnake that lays "a single, very long egg."

If the 8.8 million estimate is correct, "those are brutal numbers," said Encyclopedia of Life executive director Erick Mata. "We could spend the next 400 or 500 years trying to document the species that actually inhabit our planet."

August 23, 2011

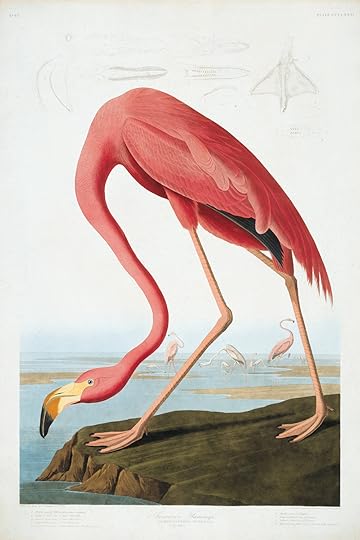

An Efflorescence of Flamingoes

American flamingo by J.J. Audubon

Natalie Angier on flamingoes, in today's New York Times:

Now they paraded forward, now they all marched aft. Now they shot up their necks like periscopes and twisted their heads first left, then right. They flashed the black petticoats of their underfeathers in single- and double-winged salutes. They moonwalked on water, raised a spindled leg balletically, from dégagé position to arabesque. They honked like indignant Canada geese and rasped like didgeridoos.

She also explains how flamingoes feed and why they so often stand elegantly on one leg:

Wherever they alight, flamingos are filter feeders, the avian equivalent of baleen whales. They skate slowly through their chosen wetland, as stiff and pompous as Monty Python's philosophers on a soccer field, treading through mud and water with their webbed feet, panning for brine shrimp, algae, insects, larvae, whatever the local microbios may be.

A flamingo submerges its head upside down, allowing its bent upper bill, with its curtain of comblike filaments, to serve as scoop and colander, all abetted by its formidable machine tool of a tongue.

"The tongue is like a piston," said Matthew J. Anderson, an assistant professor of psychology at St. Joseph's University who studies flamingos at the Philadelphia Zoo. "It moves back and forth rapidly, pumping water into the bill and then squirting it back out the sides." And so the pumping and squirting continues, until the flamingo has managed to sieve together some nine ounces of food a day.

Given their large bodies and energy-intensive feeding style, flamingos do what they can to conserve energy. Dr. Anderson, his student Sarah Williams and their co-workers have published a series of papers arguing that flamingos stand on one leg for thermoregulatory reasons — to keep themselves warm.

"Just as we hug everything into the torso when we're cold, so flamingos will hold a leg close to the body," Dr. Anderson said. "They're trying to diminish the surface area exposed to the elements."

The researchers have shown that as temperatures drop, flamingo legs rise, and that flamingos standing in water strike the unipedal pose far more often than flamingos resting on warmer ground.

August 18, 2011

Strike Up The Brand

Illustration by Eric Palma

How often does a national magazine phone up and invite you to make fun of Swedes, Latvians, Koreans, the Irish, and just about everybody else in the world? Here's the result, a story about nation branding for the back page of September's Smithsonian? (Slightly edited here to restore a few things lost for space reasons in print):

You know the sense of decorum and probity that marketing consultants have brought to our political campaigns? Now they're doing the same thing for whole countries. It's called "nation branding," a new, improved way to jostle for attention in the global marketplace. A key part of the mission is to sum up a nation in a single dazzling phrase. "Malaysia, Truly Asia," for instance, or "Chile, All Ways Surprising." South Korea briefly touted itself as "Dynamic Korea," and then switched to "Korea, Sparkling," until someone pointed out that it sounded like a fizzy drink. "Miraculous Korea" was briefly contemplated as a replacement, but finally everyone settled on "Korea, Be Inspired." ("Korea, So Good We Made Two" was never a serious contender.)

Branding a nation clearly poses many challenges. The tendency of some countries to have a lunatic for dear leader is not, however, one of them; consultants are used to that from the corporate world. But a lot of countries don't have much of an identity, as far as the outside world is concerned. They proliferate like brands of soap, with only so much sparkle to go around.

You have to sympathize with the authors of an academic article headlined "Development of a national branding strategy: The case of Latvia." But let's brainstorm here. The official Latvia travel webpage boasts that "In Latvia, there is every opportunity to receive high-level medical services." (And, OK, six Unesco World Heritage sites in an area smaller than South Carolina.) But if the idea is to dazzle tourists, investors, international agencies and the media, "Mad Men's" Don Draper would tell us to reach into their souls: "Latvia…Home of the Bacon Bun."

No doubt nation branding involves hours of patient explaining to baffled government officials why traditional ideas about identity don't matter much, compared with what the world wants. For instance, the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago's motto is "Together we aspire, together we achieve." But how about "Rum Punch on the Beach," instead? Likewise, the motto of the British Virgin Islands is "Vigilante" (Be watchful). But since BVI has built itself into a financial haven by discreetly not watching, maybe the nation brand could be something peppier, like "Fabulous Tax Schemes." India has one of the world's oldest civilizations, but to the outside world, it might as well be, "India: Where Operators Are Always Standing By." Somehow the current brand, "Incredible India," doesn't seem like much of a fix.

The best nation brands catch on and generate buzz. But they can also have a nasty way of biting back. When Ireland's "Celtic Tiger" recently went on life support from the European Union, for instance, it led inevitably to headlines about being declawed, defanged and "Too Old to Pounce." Nor did Britain do all that well by the 1990s brand "Cool Britannia." It used to seem just like a lame Austin Powersy attempt to cash in on the Fab 1960s. Then it took on a chilly new meaning this past winter, when the entire nation fell into a deep freeze. (Oddly, Jamaica relies on the overly familiar "Out of Many, One People," when the national catchphrase is clearly "Evryting Cool?" Send in the nation branders!)

With some countries, as with some political candidates, the best strategy may be to manage expectations—for instance, "China: Now 55 Percent Less Communist!" Or "Amazingly Asian Myanmar: Not Just for Jailed Dissidents!" Sweden has such a reputation for fabulously beautiful people that underselling might take some of the pressure off average-looking Swedes. What about "Eat Stinky Fish, Watch Disturbing Movies"?

The consultants themselves often seem a little vague about what they're selling. Even brands they consider genius can look remarkably interchangeable. If it's Tuesday, this must be "Amazing Thailand." Or is it South Africa "Alive With Possibility"? Did we just touch down in "Positively Transforming" Estonia? Or is it "Iceland Naturally"?

Feeling confused? Ultimately, a wishful traveler might yearn for Bolivia—or anyplace, really—where "The authentic still exists."

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Strike-Up-the-Brand.html#ixzz1VPBakp9u

August 17, 2011

A Parasite that Tricks a Rat into Becoming a Cat's Dinner

This is a good one, from Louis Bergeron at the Stanford University news service:

When a male rat senses the presence of a fetching female rat, a certain region of his brain lights up with neural activity, in anticipation of romance. Now Stanford University researchers have discovered that in male rats infected with the parasite Toxoplasma, the same region responds just as strongly to the odor of cat urine.

Is it time to dim the lights and cue the Rachmaninoff for some cross-species canoodling?

"Well, we see activity in the pathway that normally controls how male rats respond to female rats, so it's possible the behavior we are seeing in response to cat urine is sexual attraction behavior, but we don't know that," said Patrick House, a PhD candidate in neuroscience in the School of Medicine. "I would not say that they are definitively attracted, but they are certainly less afraid. Regardless, seeing activity in the attraction pathway is bizarre."

For a rat, fear of cats is rational. But a cat's small intestine is the only environment in which Toxoplasma can reproduce sexually, so it is critical for the parasite to get itself into a cat's digestive system in order to complete its lifecycle.

Thus it benefits the parasite to trick its host rat into putting itself in position to get eaten by the cat. No fear, no flight – and kitty's dinner is served.

House, the lead author of a paper about the research published in the Aug. 17 issue of Public Library of Science ONE, works in the lab of Robert Sapolsky, a professor of biology and, at the medical school, of neurology and neurological sciences.

Scientists have known about Toxoplasma's manipulation of rats for years and they knew that rats infected with Toxoplasma seemed to lose their fear of cats.

It is an example of what is called the "manipulation hypothesis," which holds that some parasites alter the behavior of their host organism in a way that benefits the parasite. There are several known examples of the phenomenon in insects.

But the details of how the little single-celled protozoan Toxoplasma, about a hundredth of a millimeter long, exerts control over the far more sophisticated rat have been a mystery.

Sapolsky's group previously determined that although the parasite infects the entire brain, it shows a preference for a region of the brain called the amygdala, which is associated with various emotional states. Once in the brain, the parasite forms cysts around itself, in which it essentially lies dormant.

House was interested in how the amygdala is affected by the parasite, so he ran a series of experiments with both healthy and Toxoplasma-infected rats. He exposed each male rat to either cat urine or a female rat in heat for 20 minutes before analyzing its brains for evidence of excitation in the amygdala.

For the experiments, he used cat urine he purchased in bulk from a wholesaler. No actual cats participated in the experiments.

House analyzed certain subregions of the amygdala that focus on innate fear and innate attraction.

In healthy male rats, cat urine activated the "fear" pathway.

But in the infected rats, although there was still activity in the fear pathway, the urine prompted quite a bit of activity in the "attraction" pathway as well. "Exactly what you would see in a normal rat exposed to a female," House said.

"Toxoplasma is altering these circuits in the amygdala, muddling fear and attraction," he said.

The findings confirmed observations House made during the experiments, when he noticed that the infected rats did not run when they smelled cat urine, but actually seemed drawn to it and spent more time investigating it than they would just by chance.

Although House doesn't have the data yet to speculate on just how the cysts in the rats' brains are causing the behavioral changes, he is impressed with what Toxoplasma can accomplish.

"There are not many organisms that can get into the brain, stay there and specifically perturb your behavior," he said.

"In some ways, Toxoplasma knows more about the neurobiology of fear than we do, because it can specifically alter it," Sapolsky said.

Because Toxoplasma reproduces in the small intestine of cats, the parasites are excreted in feces, which is presumably how rats get infected. Rats are known to be extremely curious, tasting almost everything they come in contact with. Toxoplasma is also frequently found in fertilizer and can infect virtually any mammal.

Approximately one third of the world's human population is infected with Toxoplasma. For most people, it appears to present no danger, although it can be fatal in people with compromised immune systems. It also can cross the placental barrier in a pregnant woman and lead to many complications, which is why pregnant women are advised not to clean cat litter boxes.

House said humans acquire the parasite by eating undercooked meat or "eating little bits of cat poop, which I suspect happens more often than people want to admit." Or know.

Although Toxoplasma has not been shown to have any ill effects in most people, one can't help but wonder whether it truly has no effect in humans.

"There are a couple dozen studies in the last few years showing that if you have schizophrenia, you are more likely to have Toxoplasma. The studies haven't shown cause and effect, but it's possible," House said. "Humans have amygdalae too. We are afraid of and attracted to things – it's similar circuitry."

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

August 12, 2011

Same Sex Marriage and Indian Tradition

The Suquamish tribe made the front page of today's New York Times by permitting same sex marriage. But it's worth noting that this isn't a matter of conforming to modern trends, but of returning to old customs. In The Species Seekers, I wrote about an explorer named Thomas Say, who joined the Long Expedition to the American West in 1819.

Say's attitude toward the Indians was remarkably enlightened for that day, and he made it clear that Indian attitudes toward marriage, hunting, and other matters were far more advance than those of the white settlers. In many tribes, he also reported, homosexuals are "publicly known, and do not appear to be despised, or to excite disgust."

I liked this part of the NYT article:

Yet people involved in the process say the new law was an important act of self-determination. While its specific purpose is to affirm marriage rights for same-sex couples, supporters say the law also is an effort to assert tribal culture and authority over outside influences by people whose very identities have been under assault for more than two centuries, since non-Indian settlers began arriving in the Pacific Northwest.

"The reason for passing it had nothing to do with 'What benefits do I get out of it?' " said Michelle Hansen, the tribal attorney. "You have this community saying, 'Where we can avoid discrimination, we're going to do it.' "

July 30, 2011

When Cap-and-Trade Was a GOP Bragging Point

In his column in tomorrow's New York Times, Tom Friedman writes nostalgically about a time long ago when Republicans were still capable of facing problems realistically and coming up with innovative solutions. He quotes my account of how Republicans solved the acid rain problem and fixed the hole over Antarctica by making something called cap-and-trade the law of the land.

Now they can't even deal with everyday business like paying the bills. Here's my article as it originally appeared in the August 2009 issue of Smithsonian:

John B. Henry was hiking in Maine's Acadia National Park one August in the 1980s when he first heard his friend C. Boyden Gray talk about cleaning up the environment by letting people buy and sell the right to pollute. Gray, a tall, lanky heir to a tobacco fortune, was then working as a lawyer in the Reagan White House, where environmental ideas were only slightly more popular than godless Communism. "I thought he was smoking dope," recalls Henry, a Washington, D.C. entrepreneur. But if the system Gray had in mind now looks like a politically acceptable way to slow climate change—an approach being hotly debated in Congress—you could say that it got its start on the global stage on that hike up Acadia's Cadillac Mountain.

People now call that system "cap-and-trade." But back then the term of art was "emissions trading," though some people called it "morally bankrupt" or even "a license to kill." For a strange alliance of free-market Republicans and renegade environmentalists, it represented a novel approach to cleaning up the world—by working with human nature instead of against it.

Despite powerful resistance, these allies got the system adopted as national law in 1990, to control the power-plant pollutants that cause acid rain. With the help of federal bureaucrats willing to violate the cardinal rule of bureaucracy—by surrendering regulatory power to the marketplace—emissions trading would become one of the most spectacular success stories in the history of the green movement. Congress is now considering whether to expand the system to cover the carbon dioxide emissions implicated in climate change—a move that would touch the lives of almost every American. So it's worth looking back at how such a radical idea first got translated into action, and what made it work.

The problem in the 1980s was that American power plants were sending up vast clouds of sulfur dioxide, which was falling back to earth in the form of acid rain, damaging lakes, forests and buildings across eastern Canada and the United States. The squabble about how to fix this problem had dragged on for years. Most environmentalists were pushing a "command-and-control" approach, with federal officials requiring utilities to install scrubbers capable of removing the sulfur dioxide from power-plant exhausts. The utility companies countered that the cost of such an approach would send them back to the Dark Ages. By the end of the Reagan administration, Congress had put forward and slapped down 70 different acid rain bills, and frustration ran so deep that Canada's prime minister bleakly joked about declaring war on the United States.

At about the same time, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) had begun to question its own approach to cleaning up pollution, summed up in its unofficial motto: "Sue the bastards." During the early years of command-and-control environmental regulation, EDF had also noticed something fundamental about human nature, which is that people hate being told what to do. So a few iconoclasts in the group had started to flirt with marketplace solutions: give people a chance to turn a profit by being smarter than the next person, they reasoned, and they would achieve things that no command-and-control bureaucrat would ever suggest.

The theory had been brewing for decades, beginning with early 20th-century British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou. He argued that transactions can have effects that don't show up in the price of a product. A careless manufacturer spewing noxious chemicals into the air, for instance, did not have to pay when the paint peeled off houses downwind—and neither did the consumer of the resulting product. Pigou proposed making the manufacturer and customer foot the bill for these unacknowledged costs—"internalizing the externalities," in the cryptic language of the dismal science. But nobody much liked Pigou's means of doing it, by having regulators impose taxes and fees. In 1968, while studying pollution control in the Great Lakes, University of Toronto economist John Dales hit on a way for the costs to be paid with minimal government intervention, by using tradable permits or allowances.

The basic premise of cap-and-trade is that government doesn't tell polluters how to clean up their act. Instead, it simply imposes a cap on emissions. Each company starts the year with a certain number of tons allowed—a so-called right to pollute. The company decides how to use its allowance; it might restrict output, or switch to a cleaner fuel, or buy a scrubber to cut emissions. If it doesn't use up its allowance, it might then sell what it no longer needs. Then again, it might have to buy extra allowances on the open market. Each year, the cap ratchets down, and the shrinking pool of allowances gets costlier. As in a game of musical chairs, polluters must scramble to match allowances to emissions.

Getting all this to work in the real world required a leap of faith. The opportunity came with the 1988 election of George H.W. Bush. EDF president Fred Krupp phoned Bush's new White House counsel—Boyden Gray—and suggested that the best way for Bush to make good on his pledge to become the "environmental president" was to fix the acid rain problem, and the best way to do that was by using the new tool of emissions trading. Gray liked the marketplace approach, and even before the Reagan administration expired, he put EDF staffers to work drafting legislation to make it happen. The immediate aim was to break the impasse over acid rain. But global warming had also registered as front-page news for the first time that sweltering summer of 1988; according to Krupp, EDF and the Bush White House both felt from the start that emissions trading would ultimately be the best way to address this much larger challenge.

It would be an odd alliance. Gray was a conservative multimillionaire who drove a battered Chevy modified to burn methanol. Dan Dudek, the lead strategist for EDF, was a former academic Krupp once described as either "just plain loony, or the most powerful visionary ever to apply for a job at an environmental group." But the two hit it off—a good thing, given that almost everyone else was against them.

Many Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) staffers mistrusted the new methods; they had had little success with some small-scale experiments in emissions trading, and they worried that proponents were less interested in cleaning up pollution than in doing it cheaply. Congressional subcommittee members looked skeptical when witnesses at hearings tried to explain how there could be a market for something as worthless as emissions. Nervous utility executives worried that buying allowances meant putting their confidence in a piece of paper printed by the government. At the same time, they figured that allowances might trade at $500 to $1,000 a ton, with the program costing them somewhere between $5 billion and $25 billion a year.

Environmentalists, too, were skeptical. Some saw emissions trading as a scheme for polluters to buy their way out of fixing the problem. Joe Goffman, then an EDF lawyer, recalls other environmental advocates seething when EDF argued that emissions trading was just a better solution. Other members of a group called the Clean Air Coalition tried to censure EDF for what Krupp calls "the twofold sin of having talked to the Republican White House and having advanced this heretical idea."

Misunderstandings over how emissions trading could work extended to the White House itself. When the Bush administration first proposed its wording for the legislation, the EDF and EPA staffers who had been working on the bill were shocked to see that the White House had not included a cap. Instead of limiting the amount of emissions, the bill limited only the rate of emissions, and only in the dirtiest power plants. It was "a real stomach-falling-to-the-floor moment," says Nancy Kete, who was then managing the acid rain program for the EPA. She says she realized that "we had been talking past each other for months."

EDF argued that a hard cap on emissions was the only way trading could work in the real world. It wasn't just about doing what was right for the environment; it was basic marketplace economics. Only if the cap got smaller and smaller would it turn allowances into a precious commodity, and not just paper printed by the government. No cap meant no deal, said EDF.

John Sununu, the White House chief of staff, was furious. He said the cap "was going to shut the economy down," Boyden Gray recalls. But the in-house debate "went very, very fast. We didn't have time to fool around with it." President Bush not only accepted the cap, he overruled his advisers' recommendation of an eight million-ton cut in annual acid rain emissions in favor of the ten million-ton cut advocated by environmentalists. According to William Reilly, then EPA administrator, Bush wanted to soothe Canada's bruised feelings. But others say the White House was full of sports fans, and in basketball you aren't a player unless you score in double digits. Ten million tons just sounded better.

Near the end of the intramural debate over the policy, one critical change took place. The EPA's previous experiments with emissions trading had faltered because they relied on a complicated system of permits and credits requiring frequent regulatory intervention. Sometime in the spring of 1989, a career EPA policy maker named Brian McLean proposed letting the market operate on its own. Get rid of all that bureaucratic apparatus, he suggested. Just measure emissions rigorously, with a device mounted on the back end of every power plant, and then make sure emissions numbers match up with allowances at the end of the year. It would be simple and provide unprecedented accountability. But it would also "radically disempower the regulators," says EDF's Joe Goffman, "and for McLean to come up with that idea and become a champion for it was heroic." Emissions trading became law as part of the Clean Air Act of 1990.

Oddly, the business community was the last holdout against the marketplace approach. Boyden Gray's hiking partner John Henry became a broker of emissions allowances and spent 18 months struggling to get utility executives to make the first purchase. Initially it was like a church dance, another broker observed at the time, "with the boys on one side and the girls on another. Sooner or later, somebody's going to walk into the middle." But the utility types kept fretting about the risk. Finally, Henry phoned Gray at the White House and wondered aloud if it might be possible to order the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally owned electricity provider, to start buying allowances to compensate for emissions from its coal-fired power plants. In May 1992, the TVA did the first deal at $250 a ton, and the market took off.

Whether cap-and-trade would curb acid rain remained in doubt until 1995, when the cap took effect. Nationwide, acid rain emissions fell by three million tons that year, well ahead of the schedule required by law. Cap-and-trade—a term that first appeared in print that year—quickly went "from being a pariah among policy makers," as an MIT analysis put it, "to being a star—everybody's favorite way to deal with pollution problems."

Almost 20 years since the signing of the Clean Air Act of 1990, the cap-and-trade system continues to let polluters figure out the least expensive way to reduce their acid rain emissions. As a result, the law costs utilities just $3 billion annually, not $25 billion, according to a recent study in the Journal of Environmental Management; by cutting acid rain in half, it also generates an estimated $122 billion a year in benefits from avoided death and illness, healthier lakes and forests, and improved visibility on the Eastern Seaboard. (Better relations with Canada? Priceless.)

No one knows whether the United States can apply the system as successfully to the much larger problem of global warming emissions, or at what cost to the economy. Following the American example with acid rain, Europe now relies on cap-and-trade to help about 10,000 large industrial plants find the most economical way of reducing their global warming emissions. If Congress approves such a system in this country—the House had approved the legislation as we went to press—it could set emissions limits on every fossil-fuel power plant and every manufacturer in the nation. Consumers might also pay more to heat and cool their homes and drive their cars—all with the goal of reducing global warming emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels over the next ten years.

But advocates argue that cap-and-trade still beats command-and-control regulation. "There's not a person in a business anywhere," says Dan Esty, an environmental policy professor at Yale University, "who gets up in the morning and says, 'Gee, I want to race into the office to follow some regulation.' On the other hand, if you say, 'There's an upside potential here, you're going to make money,' people do get up early and do drive hard around the possibility of finding themselves winners on this."

Richard Conniff is a 2009 Loeb Award winner for business journalism.

July 23, 2011

Nonsense About Birds

As a follow up to yesterday's post, here are some colorful names for imaginary birds by the eminent master of nonsense, Edward Lear:

July 22, 2011

A Fungus Named Hotlips

A few weeks ago, sponsored by The Guardian in the UK, which invites readers to give colorful "common" names to species only known by their scientific names. So now . A few of them seem a bit tinselly to me. And some of the entrants need a little help with their own online names: Let's just pass over trancegemeni, greenmeeny, and chatteringmonkey, and gag for a moment over the name Haggissouvlaki, which suggests someone has taken fusion cuisine a frying pan too far.

But never mind. Take a look at a photo of the overall winner in the contest, and you will agree that Hotlips certainly fits:

A lurid orange fungus, previously only known by its forgettable scientific name, Octospora humosa, was dubbed 'hotlips' by Rachael Blackman from Swindon. (Photograph: Thomas Læssøe/MycoKey/Natural England)

The judges explained: "'Hot' is a good description of its red-orange colour and this fungus often grows in tightly packed groups, causing them to curl together into shapes that closely resemble pairs of lips (and even when they are solitary they are disc-shaped with a lip around the edge). This species is also from a group of fungi called discomycetes or "discos" for short, and we loved the notion of a "hotlips disco."

The name came from 12-year-old Rachael Blackman.

Here are the nine other winners:

Chrysis fulgida

Winner

Shimmering ruby-tail – O. Holland

Runner-up

Sapphire-headed ruby wasp – loanna1301

Judges' comments: Chrysis fulgida is one of the most brightly coloured of all our wasps, and this name beautifully describes its metallic appearance in sunlight when it really can seem to "shimmer".

Chrysotoxum elegans

Winner Zipper-back – haggissouvlaki

Runner-up Elegant hover fly – Adriana Muga Forester

Judges' comments: Many hoverflies are harmless mimics of honeybees, bumblebees or, as in the case of Chrysotoxum elegans, wasps. This name cleverly depicts the discontinuous, zipper-like bands across the abdomen of this fly, instead of the continuous bands of common wasps. 'Zipper-back' is just the kind of fun, descriptive name that should get adults and children alike looking more closely at these garden visitors.

Xerocomus bubalinus

Winner Ascot hat – Pixcel

Runner-up Linden rose bollette – PhilLamb

Judges' comments: This species has only been discovered in the UK recently, and the name "Ascot hat" provides the link to the place where it was first found (in Ascot) and reminds us of its hat-like shape. Of course many people also think of hats when they think of Ascot, and we liked this clever double meaning.

Lichenomphalia alpina

Winner Sunburst lichen – Halina Pasiecznik

Runner-up Boggart's blanket – Trancegemini

Judges' comments: This lichen lives in peaty areas and looks just like a tiny burst of sunshine against the dark soil, so the name fits it perfectly.

Phallusia mammillata

Winner Neptune's heart sea squirt – greenmeeny

Runner-up Opal sea squirt – Pixcel

Judges' comments: This sea squirt is shaped very like a human heart, pumping sea water in through one siphon and out through another. As the largest of all the UK's sea squirts, it seemed appropriate to name Phallusia mammillata after Neptune, the Roman god of the sea. We did wonder if it mattered that the species is a milky white instead of red, but we decided the heart of a sea god might be any colour.

Coryphella browni

Winner Scarlet lady – TheJudderman

Runner-up Sting wraith – dandav

Judges' comments:

This species is certainly scarlet and, since it is a hermaphrodite (in other words, each individual contains male and female sexual organs) the "lady"

label is apt. But what we liked most is that "scarlet lady" implies something very beautiful but with a bit of a darker side, and this gorgeous sea slug certainly has a hidden sting: for its own protection, it recycles the stings from the jelly fish on which it preys.

Sagartiogeton lacerates

Winner Fountain anemone – Martin Cox

Runner-up Sneezing carrot – moregan

Judges' comments: This anemone has delicate translucent tentacles on the end of a more solid stalk, making it just like a fountain. The name suited it perfectly.

Ophiura albida

Winner Serpents' table brittle star – Kmnaut

Runner-up Twin-spot brittlestar – culbin

Judges' comments:

This suggestion struck us as particularly ingenious. This species can be distinguished from all other brittle stars by the paired spots at the base of

each of its snake-like arms, giving the appearance of five snakes resting their heads on a table – the spots are like the snakes' eyes. This name is both memorable and helps you identify the species, in other words just what we were looking for in a name.

Nymphon gracile

Winner Gangly lancer – TheAlnOwl

Runner-up Lowry's sea spider – chatteringmonkey

Judges' comments: This name made us laugh and brilliantly captured both this sea spider's gangly nature and its large fang-like structures (actually called "chelifores") at the front of its head.

July 10, 2011

Death of a Naturalist

Anne LaBastille, the reclusive Adirondacks naturalist, has died at 77, in a New York State health care facility where she was being cared for after having developed Alzheimer's Disease.

Anne LaBastille, the reclusive Adirondacks naturalist, has died at 77, in a New York State health care facility where she was being cared for after having developed Alzheimer's Disease.

Her obituary in The Los Angeles Times (via The Kansas City Star) described her–incorrectly–as having both discovered a species, the giant pied-billed grebe, and lived to see it go extinct. But she closely chronicled its extinction, which was the result of sports fishermen introducing smallmouth and largemouth bass into the lake where they lived. These fish out-completed LaBastille's giant pied-billed grebes for their primary food source, and the disastrous effects were compounded by the 1976 Guatamala earthquake.

Giant pied-billed grebe (Podylimbus gigas)

Her reach as an environmentalist extended to Guatemala, where she had discovered the flightless bird known as the giant pied-billed grebe at Lake Atitlan while leading nature tours in 1960.

When LaBastille returned five years later to study the rare bird, its population had declined by 50 percent. She wrote her doctoral dissertation for Cornell on the plight of the grebe, or "poc" as the bird was known locally, and spent 24 years campaigning to save it.

She persuaded the Guatemalan government to make the grebe's habitat a wildlife refuge, launched educational programs and wrote about the doomed bird in her 1990 book "Mama Poc," the nickname local residents gave her.

"Her work with the giant grebe was one of the few studies where someone, over a long period of time, monitored the extinction of a species," Lassoie said. "The work was scientific but had a real personal and humanitarian part to it."

She grew up, coincidentally, in my old home town, Montclair, NJ

June 30, 2011

Properly Screwed-Together Beetle

Papuan weevil

I don't think you can call this biomimicry, since humans invented the screw sometime around the third century B.C., and this is the first we've heard that the Papuan weevil got there first.

So maybe it's more like convergent evolution, two species arriving independently at the same solution. I have vivid memories of watching Dr. Denton Cooley perform heart surgery, and being struck by how mechanical it seemed, with veins being 45′d together the way a carpenter will 45 a joint, and lines being threaded through blind spaces the way an electrician will run a line with a fish tape. So this further instance of the mechanistic way things get put together also pleases me. Here's the press release from this week's Science:

Many innovations in modern mechanical engineering were taken directly from nature, like the ball-and-socket joint, which was first described as part of an organism's anatomy before being adapted as a machine. The classic screw-and-nut system, however, was thought to be a uniquely human innovation. Now, researchers have found an example of this screw-and-nut system in the legs of a beetle known as the Papuan weevil, Trigonopterus oblongus. (Apparently, evolution beat us to the punch on that one as well.) In a Brevium, Thomas van de Kamp and colleagues describe this functional screw-and-nut system in the weevil's coxa-trochanteral joints, one of the three major sets of joints in an insect's leg. Until now, these particular joints were considered to be hinges. But, according to the researchers, the tips of the insect's coxae closely resemble nuts with well-defined inner threads that continue internally for 345 degrees and the corresp onding trochanters have perfectly compatible external threads that cover 410 degrees. They suggest that an advantage of this system may be that the weevil's legs come to a stable resting position, which is ideal for life on twigs and foliage.

Half the weevil's leg joint with external screw thread

The other half has an internal screw thread