Richard Conniff's Blog, page 99

December 25, 2011

Beyond the Zodiac: Drones Spy on Japanese Whalers

Early this year, I reported in Smithsonian on the dawning age of civilian drones. I did not imagine Greenpeace would be among the pioneers, but Reuters reports that the environmental group is now tracking Japanese whalers from on high. The article does not say which model drone they are using, but probably better if not equipped with Hellfire missiles.

Dec 25 (Reuters) – Hardline whaling opponents attempting to stop Japan's annual whale hunt in the Antarctic said on Sunday they had intercepted and photographed its whaling fleet using pilotless drone aircraft.

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society said it located the Japanese factory ship Nisshin Maru off Australia's western coast on Saturday using the drones, the first time this season it has made contact with the whalers.

However, other Japanese ships shielded the vessel "to allow it to escape", Sea Shepherd said in a statement.

"We caught them due west of Perth," founder Paul Watson told Reuters by satellite phone from the ship Steve Irwin. "For the next few days we will be chasing them. We are heading south."

The two drones are equipped with cameras and detection equipment and allow Sea Shepherd to monitor the whaling fleet from a distance, he said.

Watson said Sea Shepherd's three ships were well outside Antarctic waters when the Japanese vessel was seen. The Sea Shepherd waited for the Nisshin Maru after hearing from fishermen it had sailed through the Lombok Strait in Indonesia on its voyage to Antarctic waters.

The Sea Shepherd society's annual attempts to stop the Japanese whale hunt by "direct action" have been widely criticised by other environmentalists and governments, particularly Japan. However, it also has influential supporters.

Watson said sympathisers in New Jersey in the United States contributed to the cost of the two drones.

An international moratorium on whaling has been in place since 1986, but Japan exploits a loophole allowing whaling for scientific purposes to justify its annual hunt.

Also of interest: This Washington Post report on the rise of the drone. And the ACLU on the dangers of domestic spying from on high.

December 23, 2011

Dispatches from the War on Stuff

This is a short piece I wrote for the back page of the January Smithsonian:

This is a short piece I wrote for the back page of the January Smithsonian:

We have a rule in my house that for every box of stuff stashed in the attic, at least one must be removed. The reality is that it would take 6—or maybe 27—boxes to make a dent in the existing inventory. But this creates a conflict with another rule against adding to the local landfill. So, for a while, I was taking things out of the attic and, for the good of the earth, hiding them in closets and under beds.

Then my grown children sat me down and said, "We love you, but…" I know how interventions work. I put on a glum face and confessed, "My name is Dad, and I am a hoarder." And with these words, I manfully enlisted in the War on Stuff.

We are all foot soldiers in this war, though mostly AWOL. Surveys say that 73 percent of all Americans enter their houses via the garage—all of them staring straight ahead to avoid seeing the stuff piled up where the cars are supposed to go. The other 27 percent never open the garage door, for fear of being crushed beneath what might come tumbling out.

It's mostly stuff we don't want. The treasures in my attic, for instance, include a lost Michelangelo. Unfortunately, it's a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle action figure my son misplaced when he was 8. There's also a yearbook from a school that none of us attended and a photograph of a handsome Victorian family, who are either beloved ancestors or total strangers who happened to be in a pretty picture frame we once bought. Two barrels ostensibly contain precious family heirlooms. I suspect that, if ever opened, they will turn out like Al Capone's vault and contain nothing more than vintage dust.

My opening salvo in the War on Stuff was not, in truth, all that manful: It was a covert mission to slip my college hookah in among the merchandise at the neighbor's garage sale. (Later I heard him exclaim, "Where the heck did that come from?" and I whispered, "Maybe you'd remember if you hadn't used it so much.") Then I tried flinging excess dog toys over a hedge into a doggy-looking yard down the street (my dog is a hoarder, too). That went well, until I hit a small child in the head. Next I tried selling an old golf putter on eBay, but after seven days eagerly waiting for my little auction to flare up into a bidding war, I came away with $12.33.

Then I discovered a web service called Freecycle, and my life was transformed. Like eBay or Craigslist, Freecycle is a virtual marketplace for anything you want to get rid of, but all merchandise is free. This four-letter word seems to unleash an acquisitive madness in people who otherwise regard garage sale goods with delicately wrinkled noses. Suddenly strangers were hot-stepping up the driveway to haul away bags of orphaned electrical adapters, a half bag of kitty litter my cats had disdained and the mounted head of a deer (somewhat mangy).

At first, I experienced twinges of donor's remorse, not because I wanted my stuff back, but because I felt guilty about having suckered some poor souls into taking it. But others clearly had no such qualms. One day my regular Freecycle e-mail came in touting an offer of pachysandra plants, "all you can dig." Another day it was "Chicken innards & freezer-burnt meat." And both offers found takers.

I soon came to accept that there is a home for every object. Well, maybe not for the construction paper Thanksgiving turkey I glued together in fourth grade, with the head on backward.

I'm adding that to a new barrel of family heirlooms that I will give my children when they buy their first homes.

December 17, 2011

A Race of Docile Copiers

The British biologist Mark Paget has an interesting article about how the evolution of ideas parallels the evolution of biological traits. Though we like to think of Homo sapiens (and ourselves) as extraordinarily creative, the truth is that real innovation is rare. Most of are just spectacularly good at copying and spreading what seem to be the best new ideas. We are champions only at social learning.

The money paragraphs suggest that social networking via the Internet tends to make copying even more pervasive, and innovation still more rare:

Putting these two things together has lots of implications for where we're going as societies. As I say, as our societies get bigger, and rely more and more on the Internet, fewer and fewer of us have to be very good at these creative and imaginative processes. And so, humanity might be moving towards becoming more docile, more oriented towards following, copying others, prone to fads, prone to going down blind alleys, because part of our evolutionary history that we could have never anticipated was leading us towards making use of the small number of other innovations that people come up with, rather than having to produce them ourselves.

The interesting thing with Facebook is that, with 500 to 800 million of us connected around the world, it sort of devalues information and devalues knowledge. And this isn't the comment of some reactionary who doesn't like Facebook, but it's rather the comment of someone who realizes that knowledge and new ideas are extraordinarily hard to come by. And as we're more and more connected to each other, there's more and more to copy. We realize the value in copying, and so that's what we do.

And we seek out that information in cheaper and cheaper ways. We go up on Google, we go up on Facebook, see who's doing what to whom. We go up on Google and find out the answers to things. And what that's telling us is that knowledge and new ideas are cheap. And it's playing into a set of predispositions that we have been selected to have anyway, to be copiers and to be followers. But at no time in history has it been easier to do that than now. And Facebook is encouraging that.

And then, as corporations grow … and we can see corporations as sort of microcosms of societies … as corporations grow and acquire the ability to acquire other corporations, a similar thing is happening, is that, rather than corporations wanting to spend the time and the energy to create new ideas, they want to simply acquire other companies, so that they can have their new ideas. And that just tells us again how precious these ideas are, and the lengths to which people will go to acquire those ideas.

A tiny number of ideas can go a long way, as we've seen. And the Internet makes that more and more likely. What's happening is that we might, in fact, be at a time in our history where we're being domesticated by these great big societal things, such as Facebook and the Internet. We're being domesticated by them, because fewer and fewer and fewer of us have to be innovators to get by. And so, in the cold calculus of evolution by natural selection, at no greater time in history than ever before, copiers are probably doing better than innovators. Because innovation is extraordinarily hard. My worry is that we could be moving in that direction, towards becoming more and more sort of docile copiers.

You can read Paget's full article here. But I am wondering if I should suggest that you copy this link to Facebook? Maybe come up with your own contrarian perspective instead, and demonstrate that innovation lives.

December 15, 2011

Bizarre Accident Kills 1500 Waterbirds

Eared Grebe (American Bird Conservancy)

I am resisting the headline about Bird-Slayer Wal-Mart, because this just seems like a horrible tragedy for everyone. Here's the press release from the American Bird Conservancy:

Officials in Utah are estimating that about 1,500 Eared Grebes were killed late Monday night, possibly as a result of confusing a Wal-Mart parking lot in Cedar City with a body of water and landing on the asphalt during a storm. An additional 3,500 apparently dazed and confused grebes were rounded up through the night by hand by volunteers and staff of the Utah Department of Wildlife, and eventually released into a nearby lake.

It appears that a storm and associated cloud cover was a key factor in causing the birds' confusion, as well as a glistening parking lot surface that may have looked like a water body in conditions of poor visibility.

According to American Bird Conservancy (ABC), the nation's leading bird conservation organization, several traits of this bird likely played a role in this incident. Grebes are only able to land and take off from water so a shimmering parking lot on a stormy night may have looked like a natural landing area. The Eared Grebe carries out the latest fall migration of any bird species in North America, putting it in this storm at a time when other migrating birds likely have already arrived South. The Eared Grebe only migrates at night, which increases the risk of the bird getting confused by city lighting and cloud cover.

"Night-flying birds use dim light from the moon and stars and the earth's magnetic field for navigation. Adverse conditions on Monday night may have caused the same kind of disorientation that can afflict pilots in fog – the birds may have flown directly into the ground, not realizing they were descending. Urban lights attract and confuse birds, so when you bring the storm into play, I think this is a serious possibility," said Dr. Christine Sheppard, Bird Collision Program Director for ABC.

"However, we will probably never know for sure exactly what happened, so it may be very hard to know if it is something that can be mitigated. Large kills of night-migrating birds are unfortunately not unusual, and are generally related to man-made light sources—from spotlights to cell phone towers. Even light from office windows, street lights, and decorative lighting can attract birds to land in cities, where they are at high risk of colliding with glass on buildings as they try to feed the next day. Reducing unnecessary lighting can reduce this type of mortality, but in the case of the grebes, we simply don't know if they took tarmac for a body of water or lost orientation," Sheppard said.

Eared Grebes are the most abundant grebe in the world. They breed in shallow wetlands in western North America. The Eared Grebe occurs in greatest numbers on Mono Lake and the Great Salt Lake in fall, where it doubles its weight in preparation for a nonstop flight to its wintering grounds in the southwestern United States and Mexico. It is a small waterbird – about 9-12 inches long – with a wingspan of about 23 inches. The bird's diet consists of mostly aquatic insects and crustaceans, occasionally tadpoles, small frogs, and small fish.

#

December 12, 2011

445 Million Years Old (and Still Having Sex on the Beach)

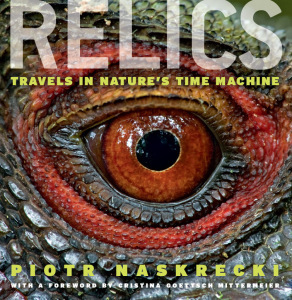

The Harvard entomologist, photographer, and writer Piotr Naskrecki has a beautiful new book out from University of Chicago Press. It's called Relics: Travels in Nature's Time Machine. Here's the publisher's description:

The Harvard entomologist, photographer, and writer Piotr Naskrecki has a beautiful new book out from University of Chicago Press. It's called Relics: Travels in Nature's Time Machine. Here's the publisher's description:

Naskrecki begins by defining the concept of a relic—a creature or habitat that, while acted upon by evolution, remains remarkably similar to its earliest manifestations in the fossil record. Then he pulls back the Cambrian curtain to reveal relic after eye-popping relic: katydids, ancient reptiles, horsetail ferns, majestic magnolias, and more, all depicted through stunning photographs and first-person accounts of Naskrecki's time studying them and watching their interactions in their natural habitats.

And here's an excerpt:

First came the big females. Nearly all had males in tow. In the dimming light we could see spiky tails of hundreds more as they tumbled in the waves, trying to get to the dry land. By the time the sun fully set, the beach was covered with hundreds of glistening, enormous animals. Females dug in the sand, making holes to deposit their eggs, nearly four thousand in a single nest, while the males fought for the privilege of fathering the embryos. Fertilization in horseshoe crabs is external, and often multiple males share the fatherhood of a single clutch. Equipped with a pair of big compound eyes (plus eight smaller ones) capable of seeing the ultraviolet range of the light spectrum, male horseshoe crabs are very good at locating females even in the melee of waves, sand, and hundreds of other males. Scientists studying this behavior suspected at first that males might be attracted by female pheromones, but as it turns out they rely solely on their excellent vision. They do make mistakes, however, and it is not rare to find males forming chains, which disperse as soon as a real female shows up.

Watching the drama of the mass spawning of horseshoe crabs is to me as close to a religious experience as I will ever get. My heart seems to slow down and a natural calmness helps me momentarily forget all the ills of the world. As strange and distant as horseshoe crabs may seem, these majestic organisms remind me that we share the same evolutionary heritage. Although our paths to what we are now diverged early, humans and horseshoe crabs at some point shared the same ancestor. It was a very long time ago. Horseshoe crabs have been around longer than most groups of organisms that surround us now. In the fossil deposits of Manitoba, the recent discovery of an interesting little creature named Lunataspis aurora proves that horseshoe crabs quite similar to modern forms were already present in the Ordovician, 445 million years ago. By the time the first dinosaurs started terrorizing the land in the Triassic (about 245 million years ago), horseshoe crabs were already relics of a bygone era. And yet they persisted. Dinosaurs came and went, the polarity and climate of Earth changed many times over, but horseshoe crabs slowly plowed forward. Yet during this time they changed surprisingly little. Species from the Jurassic were so similar to modern forms that I doubt I would notice anything unusual if one crawled in front of me on the beach in Delaware. Somehow horseshoe crabs had stumbled upon a lifestyle and morphology so successful that they were able to weather changes to our planet that wiped out thousands of seemingly more imposing lineages (dinosaurs and trilobites immediately come to mind). But despite claims to the contrary by creationists and other lunatics, they kept evolving. Modern horseshoe crabs, limited to three species in Southeast Asia and one in eastern North America, differ in many details from their fossil relatives. We know, for example, that many, if not most, fossil horseshoe crabs lived in fresh water, often in shallow swamps overgrown with dense vegetation, and some might have even been almost entirely terrestrial.

You can buy the book here.

December 11, 2011

Are Rhinos Killed for Carved Trinkets?

As the war on rhinos continues, a Telegraph reporter goes on safari with Chinese billionaires and suggests that the horns may be valued not just for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) but for elaborate carvings, as with elephant tusks:

As the war on rhinos continues, a Telegraph reporter goes on safari with Chinese billionaires and suggests that the horns may be valued not just for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) but for elaborate carvings, as with elephant tusks:

Jennifer, the daughter of one of the businessmen, mentions bribery. By this she means gifts given to win favour. There is a strong tradition of gift-giving among businessmen in China. Yahui can be translated as 'elegant bribery', which involves cultural products and artefacts. Bribery is illegal; yahui gets around the law. None of the guests I spoke to had personal experience of carved rhino horn, but they did reach a consensus: these products still hold social cachet and may be changing hands as gifts.

[Tom] Milliken [of Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring organiation] believes the 33 horns seized in Hong Kong last month were destined for Guangzhou, a key trading hub on the South China Sea with a carving tradition that dates from the Qin dynasty, 200 b.c. Discovered alongside 758 ivory chopsticks and 127 ivory bracelets, the horns may well have been on their way to becoming elegant bribes.

'There is some evidence that suggests there may be a resurgent carving industry to replicate the Ming dynasty,' Milliken says. The evidence he refers to came from a middleman who confessed to moving rhino horn to China for carvings. Grace Gabriel, the Asia director of the International Fund for Animal Welfare, says that while researching elephant ivory in China, she also found a lot of rhino horn carving.

A Kenyan petition is currently entreating Wen Jiabao, the Chinese prime minister, to 'stop the killing of elephants and rhinos across Africa'. It calls for 'an international outcry… to force the Chinese government to stop the illegal trade in rhino horn and elephant ivory before it is too late'.

Charlie Mayhew, the CEO of the charity Tusk Trust, advocates that 'African governments should stand up to the Chinese and say, "Elephants and rhino are our iconic species, in the same way that the giant panda is yours. We're appealing to you to recognise and respect these species as a part of our national heritage."'

You can read the full article here.

December 9, 2011

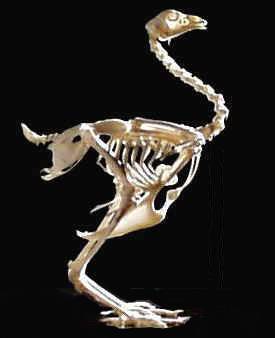

On Becoming a Science Writer

It seems to me now that my entire science education consisted of one year, seventh grade, with Dr. Kowalski, who, among other ingenious assignments, had each of us purchase a whole chicken, strip it to the bone, and then reassemble the skeleton.

It seems to me now that my entire science education consisted of one year, seventh grade, with Dr. Kowalski, who, among other ingenious assignments, had each of us purchase a whole chicken, strip it to the bone, and then reassemble the skeleton.

After that, I had a high school physics course taught by a summertime Good Humor Man, and a biology course taught by a newly-consecrated Irish Christian Brother, who found alm0st everything in biology deeply mortifying (and honestly who can blame him?). In college, I visited Science Hill just twice, first as a protester, and next for my job as a projectionist. I mostly studied poetry.

My turnabout came at the age of 25, when a magazine agreed to let me write about mosquitoes, and I suddenly found myself appalled and delighted by the incredible surgical tools in a mosquito's proboscis. I also managed to work a poem (by D.H. Lawrence) into the story, a practice I have tried to indulge ever since.

Other stories about animals and behavior followed. Dr. Kowalski's assignment even came back to me, when I found myself in Venezuela testing chicken caracasses on piranha populations, for my book Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals.

My advice to prospective science writers?

Marry money.

Sorry, just kidding. Read poetry. We need more people to recognize that the "two cultures" idea is bunk. And, really, take more science courses than I did. Lots more. I hear they are better now.

December 8, 2011

Wake up, Lysenko, Tell Lamarckists the News

In an article being published tomorrow in Cell, scientists have demonstrated that an acquired trait can be inherited, without any DNA involvement. It's the second time in recent days that scientists have hinted that Lamarckism may be more than wishful thinking.

The idea that an organism can pass on to its offspring traits acquired during its lifetime was an early theory of evolution, put forward by the eminent French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829). The idea fell into disrepute after the 1859 Darwin-Wallace discovery of evolution by natural selection. But it became a deeply dangerous idea–and Soviet national policy–in the hands of a twentieth-century follower of Lamarck, Trofim Lysenko. He argued, among other things, that he could soak wheat in frigid water and alter its DNA to make future generations more resistant to the harsh Russian winters. Under Stalin, criticism of Lysenkoism could get legitimate scientists arrested or even killed.

But now researchers are focusing on factors outside the DNA that may alter the expression of certain genes, and it seems that an individual can acquire changes in how these factors function and pass those changes on to subsequent generations. Last week, Australian scientists described a preliminary study in mice, not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal, suggesting that obese Dads can pass on a tendency to obesity to their offspring. The researchers even suggested that prospective dads should consider losing a few pounds before trying for kids. (No harm in that, but, hey, lose it for your own sake.)

The new study from Cell is of course peer-reviewed. It's about acquired immunity to disease, a subject with potential for profound evolutionary effects. But for now the researchers mostly stick to their study animal, a worm. Here's the press release:

Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have found the first direct evidence that an acquired trait can be inherited without any DNA involvement. The findings suggest that Lamarck, whose theory of evolution was eclipsed by Darwin's, may not have been entirely wrong.

The study is slated to appear in the Dec. 9 issue of Cell.

"In our study, roundworms that developed resistance to a virus were able to pass along that immunity to their progeny for many consecutive generations," reported lead author Oded Rechavi, PhD, associate research scientist in biochemistry and molecular biophysics at CUMC. "The immunity was transferred in the form of small viral-silencing agents called viRNAs, working independently of the organism's genome."

In an early theory of evolution, Jean Baptiste Larmarck (1744-1829) proposed that species evolve when individuals adapt to their environment and transmit those acquired traits to their offspring. For example, giraffes developed elongated long necks as they stretched to feed on the leaves of high trees, an acquired advantage that was inherited by subsequent generations. In contrast, Charles Darwin (1809-1882) later theorized that random mutations that offer an organism a competitive advantage drive a species' evolution. In the case of the giraffe, individuals that happened to have slightly longer necks had a better chance of securing food and thus were able to have more offspring. The subsequent discovery of hereditary genetics supported Darwin's theory, and Lamarck's ideas faded into obscurity.

However, some evidence suggests that acquired traits can be inherited. "The classic example is the Dutch famine of World War II," said Dr. Rechavi. "Starving mothers who gave birth during the famine had children who were more susceptible to obesity and other metabolic disorders — and so were their grandchildren." Controlled experiments have shown similar results, including a recent study in rats demonstrating that chronic high-fat diets in fathers result in obesity in their female offspring.

Nevertheless, Lamarckian inheritance has remained controversial, and no one has been able to describe a plausible biological mechanism, according to study leader Oliver Hobert, PhD, professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at CUMC.

Dr. Hobert suspected that RNA interference (RNAi) might be involved in the inheritance of acquired traits. RNAi is a natural process that cells use to turn down, or silence, specific genes. It is commonly employed by organisms to fend off viruses and other genomic parasites. RNAi works by destroying mRNA, the molecular messengers that carry information coded in a gene to the cell's protein-making machinery. Without its mRNA, a gene is essentially inactive.

RNAi is triggered by doubled-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is not found in healthy cells. When dsRNA molecules (for example, from a virus) enter a cell, they are sliced into small fragments, which guide the cell's RNAi machinery to find mRNAs that match the genetic sequence of the fragments. The machinery then degrades these mRNAs, in effect destroying their messages and silencing the corresponding gene.

RNAi can be also triggered artificially by administering exogenous (externally derived) dsRNA. Intriguingly, the resultant gene-silencing occurs not only in the treated animal, but also in its offspring. However, it was not clear whether this effect is due to the inheritance of RNAs or to changes in the organism's genome — or whether this effect has any biological relevance.

To look further into these phenomena, the CUMC researchers turned to the roundworm (C. elegans). The roundworm has an unusual ability to fight viruses, which it does using RNAi.

In the current study, the researchers infected roundworms with Flock House virus (the only virus known to infect C. elegans) and then bred the worms in such a way that some of their progeny had nonfunctional RNAi machinery. When those progeny were exposed to the virus, they were still able to defend themselves. "We followed the worms for more than one hundred generations — close to a year — and the effect still persisted," said Dr. Rechavi.

The experiments were designed so that the worms could not have acquired viral resistance through genetic mutations. The researchers concluded that the ability to fend off the virus was "memorized" in the form of small viral RNA molecules, which were then passed to subsequent generations in somatic cells, not exclusively along the germ line.

According to the CUMC researchers, Lamarckian inheritance may provide adaptive advantages to an animal. "Sometimes, it is beneficial for an organism to not have a gene expressed," explained Dr. Hobert. "The classic, Darwinian way this occurs is through a mutation, so that the gene is silenced either in every cell or in specific cell types in subsequent generations. While this is obviously happening a lot, one can envision scenarios in which it may be more advantageous for an organism to hold onto that gene and pass on the ability to silence the gene only when challenged with a specific threat. Our study demonstrates that this can be done in a completely new way: through the transmission of extrachromosomal information. The beauty of this approach is that it's reversible."

Any therapeutic implications of the findings are a long way off, Dr. Rechavi added. "The basic components of the RNAi machinery exist throughout the animal kingdom, including humans. Worms have an extra component, giving them a much stronger RNAi response. Theoretically, if that component could be incorporated in humans, then maybe we could improve our immunity and even our children's immunity."

The CUMC team is currently examining whether other traits are also inherited through small RNAs. "In one experiment, we are going to replicate the Dutch famine in a Petri dish," said Dr. Rechavi. "We are going to starve the worms and see whether, as a result of starvation, we see small RNAs being generated and passed to the next generation."

This research was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Gruss Lipper and Bikura Fellowships to Oded Rechavi.

December 7, 2011

Someone Went Hungry. Someone Died. Someone Rejoiced.

Fyrefly's Book Blog posted a very kind review of The Species Seekers today. She starts out with a quote that explains what the book is about much better than I have been doing lately. I apparently wrote the quote on p. 334, but time flies and memory with it:

"It is the subtext to those endless drawers of carefully arranged specimens in museums around the world: Someone had collected each specimen; killed it; skinned it; stuffed it, set it, or put it in preservative; pencil-scratched a label for it; carried it cross-country; shipped it home; studied it; and classified it – and then repeated this ritual over and over, countless millions of times. For each specimen, someone had gone hungry and sleepless. Someone alone in a remote and hostile territory had wept. Someone had perhaps drowned, been murdered, suffered malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, or typhus. Someone had certainly cursed and complained, though not so much as we might expect. Someone had said, "Hunh!" And someone had rejoiced."

Here's part of the review (I think the reviewer's name is Nicki):

I've had a growing interest in the history of science, particularly as it relates to exploration, for a while now, and The Species Seekersdid a really excellent job of putting a lot of the bits and pieces that I've acquired from other books into a broader context. This book's got the perfect balance of breadth and depth; Conniff brings a number of key figures in natural history to life through chapter-long mini-biographies, but is also always careful to keep each person's story in its relevant social and scientific setting. I also found the timeline very easy to keep straight; I often have trouble when history books jump backwards and forwards through time, but in this case Conniff keeps things mostly linear, and is very good at providing callbacks to previous chapters when necessary.

The writing is also a nice blend, using plenty of historical sources while remaining lively and engaging. It's also full of great anecdotes, and I wound up learning more than I was expecting to. I was familiar with Linneas and Cuvier and Darwin and Wallace, of course, but there were a lot of other names that I'd heard in passing but didn't know the story behind – Bates, of Batesian mimicry, for one – and plenty more cases where the people and stories Conniff included were new to me. There were also a lot of fun trivia facts. For example, even though chimps and gorillas are the most familiar non-human apes today, for a long time, all apes were referred to as "orangs," because the Dutch East India Company meant that Malaysia and Borneo were explored long before Africa was. I also liked the idea that the budding study of human parasitology helped ease the acceptance of evolutionary theory, since people were uncomfortable with the idea that God purposefully created things like liver flukes and roundworms to torment them. And, my favorite: based on the tooth shape (which is all early scientists had to go on), mammoths were originally assumed to be carnivorous, and Thomas Jefferson wrote lengthy descriptions of rampaging mammoths wreaking havoc on an unsuspecting herd of bison and doing battle with twelve-foot-tall lions (based on the claw of what would turn out to be a giant ground sloth).

The reviewer also has a few very reasonable caveats. But feel free to skip them (I may be prejudiced) and take a look at the entertaining feature on vocabulary from the book. I believe in plain words, preferably short. But apparently I quote some whoppers.,