Richard Conniff's Blog, page 96

February 1, 2012

Women Among the Early Biological Explorers

Not only was there a shortage of women collectors in my book The Species Seekers, but I also left out most of the botanical explorers. Partly that's just because I prefer writing about animals, and there weren't a lot of women out collecting animals before the twentieth century.

But Susan Branson's article from the new history web site Common-Place begins to correct both omissions. Here's an excerpt:

Merian

Women clearly were interested in botany. Whether or not botany was deemed to be a suitable occupation for women is another matter. Two gendered portrayals of female practitioners in the early eighteenth century show how some men depicted such women. German Naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian, who travelled to Surinam in 1699 with her daughter, produced a comprehensive volume, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, on the insects and flora of the colony. Merian was knowledgeable and thorough: she bred insects so she could illustrate each stage of the life cycle. A portrait painted during her lifetime shows her as a scholar, surrounded by instruments, books and the insects she studied. Yet the frontispiece to an edition of her work published after her death shows Merian seated calmly at a table while at her feet, mischievous putti rummage through collections of flora and other study objects. Alan Bewell has suggested that this maternal, rather than scientific, depiction of Merian may have "reduc[ed] social anxieties raised by the unconventional aspects of Merian's life by [intimating] that ultimately her primary commitment as a female naturalist was to domestic family life, not to the study of nature."

A retreat to domesticity in order to raise the comfort level of the early eighteenth-century readers of Merian's work was not the only strategy employed by men who encountered botanically savvy women. Charleston, South Carolina, nursery owner Martha Logan procured plants for customers in the colonies and Britain. When John Bartram met Logan during his southern tour in the 1760s, he paid her the compliment (in a letter to Peter Collinson rather than to Logan herself) that she knew her horticulture well. Logan's own letters confirm how knowledgeable she was, and they demonstrate that she was part of a local network of fellow horticulturists, some of whom were women. Logan's Gardener's Calender, which instructed southern gardeners about what, and when, to plant, was printed at the back of South Carolina almanacs until the end of the eighteenth century. Yet Bartram thought of her quite differently than he thought of male practitioners. To Collinson, Bartram described Logan as his "fascinated widow," a sexualized creature who panted after him. Bartram bragged to Collinson that he had also fascinated two other women: "two men's wives, although one I never saw; that is, Mrs. LAMBOLL, who hath sent me two noble cargoes; one last fall, the other this spring. The other hath sent me, I think, a great curiosity. She calls it a Golden Lily." Needless to say, Bartram had a rather exaggerated opinion of his ability to "fascinate." And note that he uses fascinated rather than fascinating—indicating that he had done the fascinating, not that he found these women to be so. In Bartram's depiction of Logan, Lamboll, and the unknown wife, women used plants as tribute or enticement, but not as a straightforward exchange of botanical specimens among equals.

Read Branson's full article here.

Nibbles & Poisons: A Marriage

Jameson and Friend

This is a nice press release from Wichita State, and with a decent punch line:

Deep in the corridors of Wichita State University's Hubbard Hall, two Biological Sciences faculty are intertwined in a sometimes contentious relationship.

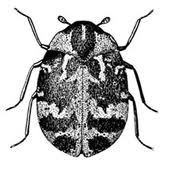

Associate professor Mary Liz Jameson is a biodiversity scientist. Her research focuses on the science of insects, specifically beetles.

Associate professor Leland Russell is a plant population and community ecologist. His research focuses on the effects that herbivores, such as beetles, have on plants.

Jameson and Russell are married. One studies beetles. The other studies plants.

Beetles eat plants. Plants can poison beetles.

Can this relationship be saved?

O.k., I'm going to skip all the cutesy marital sweet talk, and probably antagonize botanists by omitting much further discussion of Russell and his plants. (If you truly insist, you can find all that stuff here.) But I like what it says about Jameson and of course also her beetles, as well as her husband's anxieties that she might name a nice species after him (you can also check out her full bio here) :

She has discovered and named 37 new species of scarab beetles through her research in places such as Sumatra, Peru, Honduras, the Soloman Islands and Thailand. Jameson has also had several species actually named in her honor.

"Species are the pieces of the puzzle that help us to understand how all of the components of life on Earth work together," she said. "Scientists have named about 1.8 million species on Earth, but millions more remain to be described."

She has yet to name a newly discovered species after Russell, but said she's working on it.

"I haven't found just the right one to name after Leland," she said. "It's gotta be from someplace he loves. Or it's gotta have a nice smile. Or it's gotta be something that strikes me as, like, him."

Russell jokes that he'd prefer not to be named after a dung beetle.

10 Years Till Rhinos Go Extinct in Africa?

White rhino, past tense. (Photo by Richard Conniff)

At the end of my recent report on the new rhino poaching epidemic, I wrote that one park, which was once the motherlode for rhino repopulation, is no longer replacing even its own rhino population. Now South African blogger Nikela has run the numbers and suggests that, at the current rate of loss, rhinos could be extinct in Africa in 10 years.

It sounds incredible. But almost all of Africa's surviving rhino population is concentrated in one country, South Africa, which lost 448 rhinos last year. Rhinos have already gone extinct in many other African and Asian nations, including Vietnam just last year.

A big caveat: The blogger merely describes her husband, the source of the analysis, as "a numbers guy," no further credentials, nothing even remotely like peer review. So this require further work by someone with a background in large mammal demographics.

And this update, just published this afternoon in South Africa's Business Day asserts that South Africa's rhino population still has a positive growth rate. It also reports the encouraging news that a judge has just sentenced three poachers to the maximum sentence of 25 years in prison.

Meanwhile, take a look at Nikela's numbers for yourself. And keep in mind that extinction of rhinos in Africa almost happened once before, during the age of the Great White Hunters at the of the nineteenth century:

If we assume that half the rhino poached last year were female that would leave a female population of female rhino at the end of 2011 at roughly 7,620. We can deduct from this that beginning this year (2012) female rhinos will no longer replace themselves.

Or we can look at it like this: The 222 mothers killed in 2011 resulted in the loss of at least 1,100 calves. Using the same mortality, reproduction and poaching calculations that means, that in just four years we lose close to 10,000 young rhino!

In 2008 83 rhino were killed by poachers, a 638% increase from 13 in 2007. In 2009 122 were lost (147%), 333 in 2010 (273%) and an alarming 445 in 2011 (135%).

If we hypothesize that the rhino poaching rate continues unchecked at a 25% increase (assuming the anti-poaching efforts make a difference) the rhino will be extinct by 2022 or in 10 years. Even if all the female calves born in 2012 survived they would barely be old enough to have a calf before that dreadful day!

Now of course there are far too many variables to make any kind of accurate predictions. Plus we hope that the anti-poaching organizations prove successful. Thus please view these assumptions merely as a means to paint a picture of current trends and the trail to the rhinos extinction, if we can't curb the poaching and stop the illegal trafficking.

References:

Number of rhino left

http://www.worldwildlife.org/what/globalmarkets/wildlifetrade/faqs-rhinoceros.html

High mortality rates have limited the successful breeding of black rhinos

http://www.honoluluzoo.org/black_rhinoceros.htm

More male calves are born than female calves, but male mortality rate is higher, leading to adult sex ratios biased towards females. Fighting is the most common cause of adult male deaths. Most females die of old age

http://www.savetherhino.org/eTargetSRINM/site/745/default.aspx

January 30, 2012

Nasty Boys and Toxic Females

I used to think that the paradoxical platypus and certain shrews were the only venomous mammals. But it turns out that poisons, if not venoms, are surprisingly common in mammals. A recent report in Proceedings of the Royal Society B described an African rat that uses a poison to repel lions and other pesky predators. Now Natalie Angier has a roundup of mammal bad boys, all of them dabblers in nasty toxins of one sort or another. Here's an excerpt from The New York Times:

I used to think that the paradoxical platypus and certain shrews were the only venomous mammals. But it turns out that poisons, if not venoms, are surprisingly common in mammals. A recent report in Proceedings of the Royal Society B described an African rat that uses a poison to repel lions and other pesky predators. Now Natalie Angier has a roundup of mammal bad boys, all of them dabblers in nasty toxins of one sort or another. Here's an excerpt from The New York Times:

Venoms and repellents are hardly rare in nature: Many insects, frogs, snakes, jellyfish and other phyletic characters use them with abandon. But mammals generally rely, for defense or offense, on teeth, claws, muscles, keen senses or quick wits.

Every so often, however, a mammalian lineage discovers the wonders of chemistry, of nature's burbling beakers and tubes. And somewhere in the distance a mad cackle sounds.

Skunks and zorilles mimic the sulfurous, anoxic stink of a swamp. The male duck-billed platypus infuses its heel spurs with a cobralike poison. The hedgehog declares: Don't quite get the point of my spines? Allow me to sharpen their sting with a daub of venom I just chewed off the back of a Bufo toad.

Other mammals chemically gird themselves against smaller foes: Capuchin monkeys ward off mosquitoes and ticks with extracts gathered from millipedes and ants, while black-tailed deer rub themselves liberally with potent antimicrobial secretions produced by glands in their hooves. According to William Wood, a chemistry professor at Humboldt State University in California, these secretions have been shown to be effective against a broad array of micro-organisms, including acne bacteria and athlete's-foot fungus, which could explain why teenage deer are especially diligent with the hoof-rubbing routine right before the annual deer prom.

For each newly identified instance of a chemical fix, researchers seek to identify its benefits, drawbacks and evolutionary back story, and to compare it with other known cases of chemical arms. Distinctive themes have emerged.

Read the rest of Angier's article here.

January 28, 2012

Accentuating The Negative

This is one I wrote for The New York Times back before I started this blog. But it still applies, and, yes, I am still grunting.

One of the most daunting and widely repeated insights from recent social research holds, in essence, that your marriage is doomed if you and your spouse can't muster up five positive interactions for every negative one.

"Five seems like a lot," I suggested to a friend, who promptly rattled off five nice things he had done for his wife before leaving the house that morning to go for a run. It was easy stuff once you put your mind to it, he said, like making the coffee and getting the newspaper.

"Gee, that's terrific," I replied. And I immediately started thinking of his marriage as "The Gottman Wars," after the University of Washington psychologist, John Gottman, who came up with the five-to-one ratio. I imagined my insufferable friend and his wife creeping around the house before dawn desperately racking up positives to cushion the big fat negative that was burning a hole in their hearts. Meanwhile, I was having trouble getting my wife to accept that a grunt can be a positive interaction.

As a journalist, I have always regarded a willingness to state the negatives as a mark of intellectual honesty. Or maybe it was something not quite that admirable. A column I once wrote for The New York Times Magazine dwelt a little too gleefully on the pleasures of audacious speech ("The Case For Malediction"). But now I had the sinking feeling that Gottman and my do-gooder friend were right.

I thought so because of another much less popular idea from recent social science, called "negativity bias." One reason we need to be so positive — to groom, to sweet-talk, to flatter, to bring home flowers — is that people discount the positives. They don't even notice them much of the time. It has to do with "the phenomenological paleness of comforts," according to Paul Rozin and Edward B. Royzman, University of Pennsylvania researchers who have written about negativity bias in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Review. People don't generally get pleasure from their central heating, for instance. But they notice when it doesn't work. Or as Arthur Schopenhauer, the 19th-century German philosopher, put it, "We feel pain, but not painlessness."

It is, in fact, our biological nature to accentuate the negative, to dwell on the one cutting remark rather than the three or four sweet nothings. We differentiate between negative and positive events in just a 10th of a second, and the negative ones grab our attention. For instance, when researchers show test subjects a paper with a grid of smiley faces on it and one angry face, the subjects instantly zero in on the angry face. Reverse the pattern, and it takes them a little longer to pick out the solitary smile. Likewise when a boss makes four positive comments in an employee review, and one quibble, the subordinate almost invariably fixates on the quibble.

This tendency might seem perverse. But neurologists say it's a survival mechanism. A heightened focus on what can go wrong helps us deal with danger. An angry face grabs our attention more urgently than a smile because it represents a potential threat.

Negativity bias got built into our minds during millions of years of evolution because early humans who were oblivious to danger often got a brief, bloody lesson in natural selection. As Rozin and Royzman delicately phrase it, "the threat of a predator is a terminal threat." Excessive blitheness tended to get cut short, and thus became less and less common in succeeding generations. Skittishness, or negativity bias, became a distinguishing characteristic of the survivors. And it continues to drive our behavior even now, when the biggest threat in our daily lives is likely to be a difficult boss or a disagreeable spouse.

An exaggerated emphasis on the positive — Gottman's five-to-one ratio — is apparently the natural antidote at home. A long-term study of corporate management suggests that it's true in the workplace, too. Despite the ample lore about fierce executives driving up profits with their "mean business" scowls, the study found that the most productive teams managed 5.6 positive interactions for every negative. Other research has demonstrated that even chimpanzees, despite their reputation for belligerence, actually spend about 15 to 20 percent of their time grooming one another and just 5 percent fighting — a three- or four-to-one ratio.

So it starts to look like a basic primate need: To cultivate good relationships, you need to ease the innate animal skittishness of the people around you and provide them with a sense of safety, comfort and reciprocity. This is not perhaps such a startling revelation. And it is unlikely to produce an epidemic of Scrooge-like seasonal epiphanies. But for me, there is something compelling about the idea that being nice is a biological imperative, and not just sentimental humbug.

Five good deeds before breakfast still seems like a bit much. But when I grunt at my wife these days, I am striving to sound less like a hungry predator.

January 27, 2012

Making the First Great Evolutionary Sensation

W ho was "Mr. Vestiges" who first shook the world with his evolutionary thinking?

ho was "Mr. Vestiges" who first shook the world with his evolutionary thinking?

1. The celebrated biological thinker Charles Darwin

2. The Edinburgh journalist Robert Chambers

3. The Engish mathematician and philosopher Charles Babbage

4. Botanist and explorer Joseph Dalton Hooker

And the answer is

Robert Chambers.

Here's the story from The Species Seekers by Richard Conniff:

Evolutionary ideas, first loosely formulated decades earlier by Erasmus Darwin in England and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in France, among others, were massing beneath the surface during the first half of the 19th century, building up pressure, distorting the surface crust of conventional discourse, flaring up in odd corners of the intellectual world. Then, in October 1844, with the appearance of an anonymous tract called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, they burst out onto the public streets, up church aisles, and into coffee shops and gentlemen's clubs. Vestigeswas an almost miraculous work, deeply flawed, brimming over with "dangerous" ideas, and yet wildly popular.

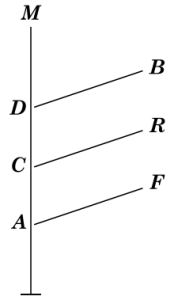

Diagram from the first edition shows a model of development where fish (F), reptiles (R), and birds (B) represent branches from a path leading to mammals (M)

The anonymous "Mr. Vestiges," as the author became known, deftly wove evolution into a sweeping history of the cosmos, beginning in some primordial "fire mist." At the very moment when Darwin thought that admitting to belief in the mutability of species was like "confessing a murder," the anonymous author of Vestiges plainly declared that humans had arisen from monkeys and apes. "In many ways," Darwin scholar James A. Secord writes, "Darwin had been scooped…" Darwin and others in the scientific community soon suspected that the real author was an outsider, the Edinburgh journalist and publisher Robert Chambers. Vestiges was so controversial, however, that his authorship was not acknowledged until after his death in 1871.

Though Vestiges is largely forgotten today, it would alter the course of public opinion, and set both Darwin and an unknown surveyor named Alfred Russel Wallace onto career paths that would converge, years later, in the triumph of evolutionary thinking.

The Species Seekers Quiz: A Movement to Make Museums New

What spurred the 19th-century "new museum" movement?

1. Generous donations from American "robber baron" railroad magnates

2. The British urge to out-compete the museums of rival nations

3. Dermestid beetles, which ruined many old museums

4. Advances in taxidermy

And the answer is

Advances in taxidermy.

During the second half of the 19th century, taxidermists had rapidly become more skillful and they now wanted not merely to educate but to excite the public with dioramas rendering dramatic scenes from the wild.

In 1869, the French naturalist and specimen dealer Jules Verreaux depicted a lion rearing up to claw an Arab courier down from the back of a camel (seen below), an exhibit that drew crowds to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

A few years later, the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., displayed "Fight in the Tree-Tops," a scene of "immense and hideously ugly male orang utans fighting furiously," with blood gushing from the wound where one sank his fangs into the other. Critics worried about a certain lack of scientific probity. But a defender responded, "If you cannot interest the visitor you cannot instruct him; if he does not care to know what an animal is, or what an object is used for, he will not read the label."

Recreating a moment from nature in a good diorama required fresh skins of the featured species, and also all the attendant details of its habitat, down to rocks and grass. So instead of simply buying specimens, or accepting them as gifts, museum curators and taxidermists now had to go out and become field collectors themselves. It was the beginning of the "new museum movement," and the comprehensive survey collections they brought back served the needs of showmen and scientists alike. Read more in The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth by Richard Conniff.

January 25, 2012

The Dance of the Dung Beetles

After they have gathered a ball of dung, but before they wheel it away from the dung heap, dung beetles always climb on top and spin around in a little dance. It looks like a moment of triumphant celebration, and one we can all identify with as we slog through our version of the same old shit. But it turns out they are actually just taking a compass reading.

After they have gathered a ball of dung, but before they wheel it away from the dung heap, dung beetles always climb on top and spin around in a little dance. It looks like a moment of triumphant celebration, and one we can all identify with as we slog through our version of the same old shit. But it turns out they are actually just taking a compass reading.

Here's the report from Science Daily:

Dung beetle dance provides crucial orientation cues: Beetles climb on top of ball, rotate to get their bearings to maintain straight trajectory.

The dung beetle dance, performed as the beetle moves away from the dung pile with his precious dung ball, is a mechanism to maintain the desired straight-line departure from the pile, according to a study published in the Jan. 18 issue of the online journal PLoS ONE.

The purpose of this dance, in which the beetle climbs to the top of the ball and rotates, had previously been unknown, so the authors of the PLoS ONE study, led by Emily Baird of Lund University in Sweden, investigated the circumstances that cause the beetle to dance.

They found that the beetles are most likely to perform the dance before moving away from the pile, upon encountering an obstacle, or if they have lost control of the ball, suggesting that the behavior is crucial for keeping the ball moving in a straight line.

Such direct, efficient navigation allows the beetle to quickly move away from the intense competition from other beetles at the dung pile. The authors propose that the beetles store a compass reading of celestial cues during the dance, which they then use to guide their straight-line trajectory.

So it's all about geography, not poetry. Even so, musicians, rise up! We need a modern-day Bela Bartok or Edvard Grieg to celebrate this particular peasant dance.

Emily Baird, Marcus J. Byrne, Jochen Smolka, Eric J. Warrant, Marie Dacke. The Dung Beetle Dance: An Orientation Behaviour? PLoS ONE, 2012; 7 (1): e30211 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030211

Impression Management 101

I watched the news without sound at the gym last night and was impressed by how NBC anchor Brian Williams always manages to keep the inside of his right eyebrow cocked up, to look like an inquiring reporter. It is almost as good as the real thing. Does he do exercises for that?

I watched the news without sound at the gym last night and was impressed by how NBC anchor Brian Williams always manages to keep the inside of his right eyebrow cocked up, to look like an inquiring reporter. It is almost as good as the real thing. Does he do exercises for that?

You can read one of my past articles about facial expressions here, and a profile of the founder of the science of facial expressions in my book The Ape in the Corner Office.

January 24, 2012

The Species Seekers Quiz: A Different Kind of Precious

Who or what is The Precious Wentletrap?

Who or what is The Precious Wentletrap?

1. An orchid once regarded as a remedy for syphilis.

2. An audacious neo-punk Trapp Family tribute band.

3. A bird so rare that a half-dozen biological explorers lost their lives in the search for it.

4. An unusually ornate shell.

And the answer is

The Precious Wentletrap, a pale spiral of shell enclosed by slender vertical ribs, first appeared in print in Georg Eberhard Rumpf's The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet, an 18th century guide to the wonders of the East Indies. Many collectors then thought that only God could have created such a "work of art." This religious spin enabled the wealthy to present their lavish collections of wentletraps and other precious specimens as a way of glorifying God rather than themselves. During the height of the Dutch shell madness (right up there with tulipmania, though less well known), a single shell once sold for more than Vermeer's now priceless "Woman in Blue Reading a Letter."

The Precious Wentletrap, a pale spiral of shell enclosed by slender vertical ribs, first appeared in print in Georg Eberhard Rumpf's The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet, an 18th century guide to the wonders of the East Indies. Many collectors then thought that only God could have created such a "work of art." This religious spin enabled the wealthy to present their lavish collections of wentletraps and other precious specimens as a way of glorifying God rather than themselves. During the height of the Dutch shell madness (right up there with tulipmania, though less well known), a single shell once sold for more than Vermeer's now priceless "Woman in Blue Reading a Letter."

You can read more in The Species Seekers, or check out this article I wrote for Smithsonian called "Mad About Shells."