Richard Conniff's Blog, page 93

March 16, 2012

The Slave Connection (Ivory part 5)

It's possible George Read had gone into the ivory business in the first place because he believed it to be free of messy moral complications. He probably knew of his fellow abolitionist Moses Brown, just up the Boston Post Road in Providence, Rhode Island. Brown had denounced his own early involvement in slaving voyages, as a young man in his family's mercantile firm. But he also made it clear that he regarded ivory as a moral alternative for the Africa trade.

The map of Africa then was a blank, and few Westerners knew where the ivory came from or how it reached the African coast. That began to change only after 1830, when a Salem, Massachusetts, merchant named John Bertram set up a trading station in Zanzibar, which was to supply the bulk of the world's ivory for the remainder of the century. In 1844, a Bertram employee there noted, without comment: "It is the custom to buy a tooth of ivory and a slave with it to carry it to the sea shore. Then the ivory and slaves are carried to Zanzibar and sold." The slaves, he added, were "discharged in the same manner as a load of sheep would be, the dead ones thrown overboard to drift down with the tide…the natives come with a pole and push them from the beach."

The trip from the mainland across to Zanzibar was only about 20 miles, but it came at the end of ivory caravans that had often traveled hundreds of miles from the interior. Arab traders led these caravans deeper and deeper inland, bringing trade goods supplied by the Zanzibar merchants, notably gunpowder and the Massachusetts-made cotton cloth known everywhere as merikani. In 1848, one of the Connecticut River Valley's own sons went to Zanzibar to trade cloth, gunpowder and kerosene for ivory. George A. Cheney, later employed at Comstock, Cheney in Ivoryton, proudly reported that he once purchased 60,000 pounds of ivory brought in by a single caravan.

Back home in Deep River, George Read was certainly aware of delays in getting the ivory down to the coast, because of the resulting fluctuations in supply and price. But perhaps mercifully, he died in 1859, just as Western explorers in Africa were beginning to reveal the horrific details of the trade. The standard procedure, they reported, was for the Arab trader to befriend tribal chiefs, use their help to empty an area of tusks, then slaughter their former allies, burn their villages, and chain up the survivors to carry tusks down to the coast. A French traveler wrote that caravans abandoned their dead and dying to the hyenas. An English missionary reported that slaves who could no longer carry their tusks were left close to the water so the crocodiles could take them.

In 1882, a missionary met up with the ruthless trader Tippoo Tib as he was leading a caravan down to Zanzibar. Pairs of slaves carrying tusks were fastened at the neck with wooden poles, the missionary wrote, and "the neck is often broken if the slave falls in walking." Many of the women carried babies on their backs as well as a tusk on their heads, and if a woman became too weak to carry both, a trader told him, "We spear the child and make her burden lighter."

Tippoo Tib's caravan took more than a year to force its way down to the coast, because a local chieftain named Mirambo had blockaded all trade at Lake Tanganyika. Ernst Moore, an ivory trader who represented Pratt, Read in Zanzibar, later wrote about the expedition in his 1931 book Ivory–Scourge of Africa: "During this year and more, when no ivory of consequence was arriving at Zanzibar on account of Mirambo's blockade, the Yankees in the Connecticut ivory-cutting factories were starving for ivory tusks. The arrival of Tippoo, with tons and tons of ivory, and the news that he had arranged peace with Mirambo and that the trade route was again open, were hailed with shouts of joy that reverberated from the eastern coast of Africa to the inner shores of Long Island Sound."

(to be continued)

March 15, 2012

A Badge of Gentility (Ivory part 4)

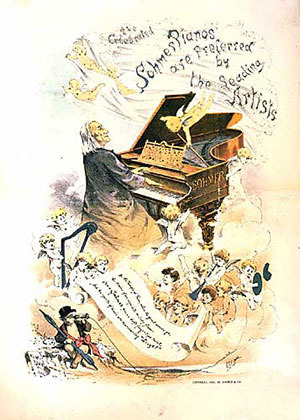

For the Victorian era, the piano "a badge of gentility," as one social observer put it, "being the only thing that distinguishes 'Decent People' from the lower and less distinguished … 'middling kind of folks.'" Every respectable parlor had a piano, and like television and the computer today, it drew people away from public entertainments and back into the home. There was, however, nothing passive about it. "Every American woman feels bound to play the piano, just as she feels bound to wear clothes," a French visitor reported in 1860. Men were expected to sing along, or at least clap appreciatively.

For the Victorian era, the piano "a badge of gentility," as one social observer put it, "being the only thing that distinguishes 'Decent People' from the lower and less distinguished … 'middling kind of folks.'" Every respectable parlor had a piano, and like television and the computer today, it drew people away from public entertainments and back into the home. There was, however, nothing passive about it. "Every American woman feels bound to play the piano, just as she feels bound to wear clothes," a French visitor reported in 1860. Men were expected to sing along, or at least clap appreciatively.

Lowell Mason of the Boston Academy of Music had recently launched the "better music" movement, which saw music as the path to "the perfecting of man's emotional and moral nature." For newly wealthy Americans, the piano was the best available means for tapping "what is most deep and holy … in the soul of man," as another musical proselytizer put it. Earnestly practiced scales and arpeggios drifting out open windows onto elm-lined streets thus became the standard background music of small town life.

Popular tastes didn't always follow the edifying path Mason had in mind. Among the favorite themes in popular sheet music, according to one writer, were "dead babies, crippled children, blessed old decrepit grandparents, dying sweethearts, and ascents into Heaven." Even classical performers found gimmicks essential for luring American hoi polloi through the door. The Austrian virtuoso Leopold de Meyer promised to perform melodies on the piano with elbows, fists, and even a cane. New Orleans concert pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk kept audiences awake by playing "Yankee Doodle" with one hand and, at the same time, "Hail Columbia" with the other. Duly inspired, their many admirers went out to buy pianos of their own. Like newly wealthy people in the developing world today, Americans yearned for a cultural refinement they could not yet quite comprehend. Such companies as Steinway, Chickering, Baldwin, and Aeolian ("Yoly-yoly" to immigrant workers back in the ivory factories) rose up to serve that need.

All of them required the exquisite luster of ivory. "It is yielding to the touch, yet firm," one writer explained, "cool, yet never cold or warm, whatever the temperature; smooth to the point of slipperiness, so that the fingers may glide from key to key instantly, yet presenting just enough friction for the slightest touch of the finger to catch and depress the key and to keep the hardest blow from sliding and losing its power." When Stephen Foster wrote "My Old Kentucky Home," and when Scott Joplin composed "Maple Leaf Rag," they played on ivory that almost certainly came from the factories in Deep River and Ivoryton.

By the turn of the century, Pratt, Read was sometimes cutting 12,000 pounds of ivory a month, almost entirely for the piano trade. Tusks then averaged sixty or seventy pounds apiece, so the Deep River factory by itself accounted for the deaths of well over a thousand elephants each year. The human toll inflicted by the ivory trade is harder to calculate. But the explorer Henry M. Stanley once loosely estimated that every pound of ivory "has cost the life of a man, woman, or child" in Africa. In the Connecticut River Valley, it took a pound and a half of ivory to make a single keyboard.

(to be continued)

March 14, 2012

The Touch of Ivory (Part 3)

Two tusks, then worth $1500 in Deep River

In truth, ivory was simply another commodity then, and one that seemed to be available in almost limitless quantities. As a result, a retired ivory trader would later write, the children of Deep River and Ivoryton for generations were "born to the touch of ivory and have cut their teeth on ivory rings." When I lived there in the 1980s, the old factory was abandoned and no tusks had arrived there in 30 years. But it was still possible to find people who had grown up like that and gone on to spend their careers working with elephant tusks in the local factories. I remember one of them who recalled swimming in a local pond with his boyhood friends, at a time when so much ivory sawdust washed down from the factory that it covered them head-to-toe. "We'd come out looking like the Gold Dust Twins. My God, how my mother would holler."

Ivory trinkets still frequently turned up at tag sales, and newcomers restoring old houses were sometimes astonished to discover that their doorknobs had been

made from elephant's tusks. One day, an oddly angled glass structure rotting in a side yard caught my attention. It turned out to be an old bleaching shed, designed for holding racks of cut ivory up to the whitening power of the sun. At the height of the business, an entire field of these glass houses stood behind the ivory factory, and Read himself kept a careful journal, totting up the 30 days of sunlight needed to turn the ivory white. "No sun! No bleach day! No nothing!!" he lamented, during a cloudy March of 1852. But a break in the dreary weather also moved him to exultation: "Rejoice! Oh ye Comb-makers for today are ye blessed with

At the bleaching sheds

sunshine!"

It's hard for us now to grasp the extraordinary intimacy with elephant tusks that was once commonplace in town. These days, scientists tracking the illegal ivory trade can map the provenance of a tusk by studying its isotopes, persistent biochemical traces of what the elephant ate and where it lived. But the old ivory cutters had something like that knowledge in their hands. They could tell Congo ivory from Sudanese, Mozambique, Senegalese, or Abyssian ivory, Egyptian soft from Egyptian hard, Zanzibar prime from Zanzibar cutch. They knew it not just by how it responded to their saws, but by how it felt beneath their fingertips. "To observe a man at work with ivory," a reporter who visited the Pratt, Read cutting rooms once wrote, was "to watch a man in love. As it is sorted, sliced, cut, and matched, each workman actually fondles and caresses it."

Nobody in the factories would have phrased it quite that romantically. The work started with "junking" tusks into squared-off cylinders. A skilled marker then studied each cylinder and drew a precise map on one end to identify the least wasteful pattern of subsequent cuts. As the ivory went under the saw, a jet of water played over the surface to prevent burning. Even so, the air in the workrooms was filled with ivory sawdust, and what the reporter called "a penetrating, unpleasant odor not unlike the smell of burning bones."

"To tell you the truth, I didn't think much of it," an old ivory cutter once told me. "Your hands were in water all day and once in a while you'd hit a pus pocket in the ivory and—whoosh, it would smell." Bullets embedded in the tusk were also a frequent hazard.

Every scrap and wedge of ivory got cut into some useful product, from cutlery handles to collar buttons and nit combs (small and fine-toothed for picking lice and their eggs out of the hair). The sawdust that didn't wash down into the river served to fertilize tomatoes in local gardens. "Nothing was wasted out of those damned elephant tusks," another worker told me.

But what the ivory workers of the Connecticut River Valley came to know best was the art of cutting tusks into narrow, four-inch-long blocks, and wider, two-inch-long blocks. These blocks then had to be "parted" horizontally into veneers, at a rate of 16 per inch. The narrow veneers, called tails, were then glued down between the black keys on a piano, while the wider veneers, or heads, went on the front of the piano key, where the fingers touched. Beginning in the early 1850s, when this country produced just 9,000 pianos a year, the business boomed. By the peak year of 1910, when production hit 350,000, this country had become the largest manufacturer of pianos—and ivory keyboards–in the world.

(to be continued)

March 13, 2012

Moral Complications (Ivory part 2)

Read

The father of Deep River was a man acutely attuned to moral complications. George Read was six feet tall, blue-eyed, clean shaven, and with a quiet, self-effacing manner. As a young man at the beginning of the nineteenth century, he built a dam on the village's namesake river, with a waterwheel to drive the saws in a small shop. There a couple of men cut ivory into hair combs and other knickknacks. Working with elephant tusks was already a local industry, probably through trade between the Connecticut River's coastal sea captains, and the trans-Atlantic merchants in New York, Boston, or the Caribbean Islands. But Read found a way to build his business into a major company, and it would eventually employ hundreds of local residents.

He was a deeply scrupulous man on the familiar New England model, a careful steward of time and money, practical and relentlessly industrious. At a time when a fortune of $100,000 made a man rich, he believed that "no Christian man ought to accumulate over $25,000," and he was apparently generous enough to live and die by this rule. He made the rounds of the village several times a day to keep tabs on its progress, and he founded the Baptist church, the local bank, and the town cemetery. At one point, his wife mentioned to him that the townspeople were gossiping about some transgression he had supposedly committed, and Read replied with a characteristic blend of reticence and quick conscience, "No, I did not do that, but I do worse things."

Read's strong sense of moral responsibility led him to become an abolitionist, at a time when it was still dangerous to do so. There was a risk that Southern customers might shift their business to ivory companies in England, and even in Connecticut itself, where slavery was not entirely abolished until

Winters

1848, riots sometimes broke out when anti-slavery activists spoke. But Read was already an active stationmaster on the Underground Railroad in 1828, when a fugitive slave from the Carolinas showed up at his door seeking refuge. Billy Winters, a name given to protect him from recapture, remained in the Read family home for the next 20 years and went to work in the ivory business. Read founded the local branch of the Anti-Slavery Society, which had more members in the backwater village of Deep River than in New Haven. He seems never to have recognized a horrible irony: His own business depended entirely on slave caravans to carry the tusks from the African interior down to the coast.

(to be continued)

March 11, 2012

A Story for China from a Small New England Town (Part 1)

While I am off the grid for the next few weeks, I'll try to set up posts for a few of my stories, Here's one I wrote for the April issue of American History magazine, about the ivory trade, past and present:

Last summer on the island of Zanzibar, off the East Coast of Africa, authorities seized a stash of more than 1000 elephant tusks. The contraband had been hidden in sacks of dried sardines, in a container about to be shipped to Asia. Such incidents are becoming alarmingly common again, after a 20 year hiatus when poaching seemed to have come under control, and scientists estimate that 40,000 elephants are now being slaughtered each year for their tusks. Wealthy people in China and India come in for most of the blame and probably deserve it: They want ornately-carved pieces of ivory as symbols of their new-found prosperity.

But it reminds me of a time when Americans behaved in much the same fashion, not least in my old home town of Deep River, Connecticut. I used to live there in a house that looked out across the broad green hills of the lower Connecticut River. It was (and remains) an idyllic little New England town, with a white clapboard Congregational Church on the green, and a picturesque little landing down by the river.

The town grew up in the nineteenth century around Pratt, Read & Co., a maker of piano keyboards, at a time when the piano in the parlor was the essential symbol of middle class wealth. In the post-Civil War prosperity of 1867, the Atlantic Monthly called the piano "only less indispensable than a kitchen range." And all piano keyboards then were of course covered with ivory.

The Pratt, Read factory stood at one end of my street. At the other end, just below my house, was the river landing that once served as the unloading point for ivory shipped from Africa–by way of Zanzibar, coincidentally. An old photograph at the Deep River Historical Society showed a common sight in town then–a horse-drawn cart loaded with 32 tusks, laid down side by side like huge fingernail clippings, and said to be worth $9,000.

Pratt, Read's only competition was Comstock, Cheney & Co., in the neighboring village of Ivoryton, and together they dominated the piano keyboard business in North and South America. At the height of the public craze for the piano, from about 1860 to 1930, their business helped determine demand for ivory in Zanzibar, the major trading center, and even the price paid for tusks in the East African bush, where the elephants were being killed. About 50,000 elephants died each year then to supply the ivory trade. At the risk of overstating the moral complications of what seemed like an innocent pastime, they died so young girls could display their musical talent, and families could gather around the piano to sing.

(to be continued)

March 7, 2012

Paramaribo Walkabout (Carefully)

Paramaribo street scene

Getting ready to fly out to Palumeu, and off the grid, first thing tomorrow, if weather allows. (It's been raining heavily so far.) I did some last minute shopping (umbrella!) and visited some of the main attractions of the city this morning.

Paramaribo is no place for pedestrians. In the old city, full of colonial era wooden houses built in a Dutch style, most houses have a second story balcony over the sidewalk, but also a stoop projecting out to the curb. So you have to go continually up and down if you want to stay under the shelter of the balcony. Or you get forced out into the rain and the traffic. Cars park everywhere on the sidewalks, but if you go into the street, the drivers act as if you are unimaginably out of order and they generally move to summary execution.

Still, plenty to see, particularly the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, a nineteenth-century Gothic cathedral, with all the familiar details, the carved bases and capitals, the second-story colonnaded gallery, the groined ceilings–but all in wood. A delicate band box for the temporary storage of souls. Said to be the largest wood structure in the Western Hemisphere, 161 feet long by 54 wide, built out of rain forest and struggling with every water stain and rusting nail to get back to it. (Think about the termites!) It was pouring rain out, but I also had the illusion the walls were almost translucent, so the sun could glow through on bright days.

I took some photos with my iPhone:

March 6, 2012

Off The Map

Suriname Wildlife, as depicted by Maria Sibylla Merian, the German artist and naturalist in the eighteenth century.

I arrived last night in Paramaribo, Suriname, to join an expedition in search of new species, in the unexplored southeastern corner of the country, deep rainforest on the northern border of Brazil. It's a big expedition, including 20 or so scientists from all specialties, and also requiring lots of logistical advance work.

A Cessna Caravan will ferry us out Thursday from the capital city of Paramaribo maybe 175 miles south to our jumping off point at . Then on Friday, we'll travel by helicopter over the Kasikasima outcrop out to our first research camp, where an advance party should have cleared a heli-pad out of the forest. After nine days there we'll traveling down along the Palumeu River to a second camp for a six-day stay.

But there are lots of uncertainties in this kind of trip. We'll also be out of internet contact till the end of the month, though it may be possible to send Twitter messages out via satellite phone (you can follow me @RichardConniff).

Meanwhile, I'm taking in Paramaribo, and thinking about early explorers like Maria Sybella Merian, an eighteenth-century artist, who painted one of my favorite images of Suriname wildlife (above), a blend of fantasy from the Bestiary era with the astonishing real-world finds of the Great Age of Discovery.

Also thinking about John Stedman, a mercenary who came here in the eighteenth-century as part of a Dutch expedition to suppresst runaway slaves. I wrote about him in The Species Seekers:

Stedman

Stedman's colorful memoir was a bestseller of 1796, under the ponderous title Narrative of a Five Years' Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America, from the year 1772 to 1777. The book was partly a picaresque adventure tale, told on the ribald model of Henry Fielding's Tom Jones. It was also an indictment of slavery, though the author was hardly an abolitionist. And, oddly, it was a celebration of South American wildlife.

The mix of elements could be jarring. Along with an account of how a planter's jealous wife had slit a slave girl's throat, stabbed her repeatedly in the breast, and tossed her into a river with hands bound behind, Stedman also offered his readers loving descriptions of spider monkeys, flying squirrels, cockatoos, and coatimundis. One illustration, by Stedman's friend, the poet and artist William Blake, depicted a slave hung from the gallows, still living, by a hook jammed under his ribs, and the next showed

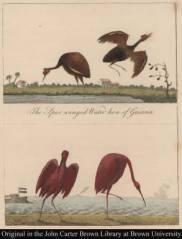

Spur-winged water hen

"The Toucan and the Fly-catcher." After "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave," the reader could contemplate "The Spur winged Water hen" and "the Red Curlew."

Taking delight in the natural world was a way of coping that suited Stedman's "incurable romanticism," according to the historians Richard and Sally Price. His descriptions of the natural world were vivid enough that they may have served as a source for Blake's famous verse "Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright/In the forests of the night …" (Stedman wrote of a "Tiger-cat," or jaguar, "its Eyes Emitting flashes of lightning.")

Everybody's a little nervous about the expedition ahead, but also excited. At lunch today, one of the scientists was talking about having once previously had a chance to visit a place like this, so untouched that the animals came close, curious, and unafraid, not knowing yet what humans could be.

March 2, 2012

Three Meals Away from Anarchy

The Ecologist, a British magazine, has an intriguing interview with theologian Martin Palmer. He's co-founder of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC) and his book Sacred Land (Piatkus) came out yesterday in the United Kingdom and appears to be available on Kindle. He has some good, contrarian stuff to say about our global rush from the countryside into cities, and also about the misguided inclination among environmentalists to justify protecting the natural world on utilitarian grounds. Here's an excerpt from the interview:

The Ecologist, a British magazine, has an intriguing interview with theologian Martin Palmer. He's co-founder of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC) and his book Sacred Land (Piatkus) came out yesterday in the United Kingdom and appears to be available on Kindle. He has some good, contrarian stuff to say about our global rush from the countryside into cities, and also about the misguided inclination among environmentalists to justify protecting the natural world on utilitarian grounds. Here's an excerpt from the interview:

You mention the abandonment of London in past crises, do you think cities are particularly at risk?One of the trends that most alarms me about contemporary thinking, say within the United Nations, is this drive to speed up the movement of people from the countryside into the cities so that you can industrialise the countryside. If you've got the people in the cities, the theory goes that it's much easier to supply them with food, warmth and energy, and you industrialise nature.

But cities live off the countryside, not the other way round. Think of all the great disaster movies: they're right. What will happen in a crisis is everybody will try and escape to the countryside. We are almost wired to relate survival and sustainability with not being in cities. Building the mega-cities where you rely upon transport to get you 30 miles from your suburb into the middle of Shanghai, or where you rely on airplanes bringing you orange juice from Kenya into central London, nice, but not sustainable. It's so fragile, we saw that with the Volcanic ash incident two years ago, in one week we had people in complete panic.

If you get a collapse in nature, and the only communities you've got are huge and entirely reliant upon a tiny group of workers to provide food, clean water and energy, if those groups are affected, if there is a collapse, if you can no longer transport food, no longer grow the food, if the soil is eroded, if the Sun's gone because of volcanic ash or even our own activities and disasters, then those communities have no ability to actually eat anything on the land. And if you look at all the great collapses of civilisations, it's the cities that go first. There was a very famous statement by the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Second World War, William Temple, and I think it sums it up, 'we are only 3 meals away from anarchy.' if you're heading towards your third missed meal and there's nothing in the local Tesco express, what do you do?

How important are both the countryside and nature to human existance?

I think knowing about the countryside is crucial because we are a grazing species and in order for us to graze, we need the crops and the materials to graze upon. And the destruction of the countryside, whether that's through urbanisation, industrialisation, soil erosion, deforestation, it's almost like a suicide pact. We need this to sustain us. But also we are a species that has the capacity to wonder. One of the great mistakes in the environmental movement is to become utilitarian. To argue for example that why we keep the Amazon is because it's a carbon sink. Well, maybe it's the fact that a third of all species live in the Amazon is another reason for preserving it. Yes, we need the countryside and we need nature to keep us alive, but we are not the only creatures on this planet that have the right to be fed and kept alive by nature as part of nature.I think we've got to start shifting the discussion away from 'what can we do to survive?' to 'what can we do to ensure that nature survives, and therefore, we survive?' I think we have to remember we are a wondering species, we are the ones that gaze the stars and wonder who the hell we are, we are the ones who sit by the sea and look at the infinity of the sea disappearing into the horizon and see that as a metaphor for our own lives. And at the moment we purely become concerned with nature as something that sustains us, rather than feeds us spiritually, psychologically and emotionally, I think we've lost the plot.

February 29, 2012

Kickstarter for a Species Seeker

I'm borrowing this, with thanks, from Bug Girl's Blog because it's a great cause. I've traveled with Brian Fisher and his team as they hunted for new ant species in Madagascar, and they do great work. You can read that story here and in my book Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time. I'm also a fan of Kickstarter, the fundraising site for creative projects. My daughter recently raised funds there to do an art project about my father as an Outsider Artist. So it's great to hear that crowdsource project funding has now come to science, too:

Earlier this week, the internets were buzzing with a claim that Kickstarter is funding more projects than the National Endowment for the Arts. It turns out that may not be strictly true, but it certainly is true that a lot of cool projects are being crowd-sourced that otherwise would never have made it off the ground.

I've mentioned some insecty Kickstarter projects before, like Meet The Beetle (a film about an endangered tiger beetle). Unfortunately, Kickstarter is limited to arts and humanities. But now the concept of crowdsourcing has been harnessed for science!

Petridish.org is so new it hardly has a bacterial film growing on its website yet. Its first science crowd-sourcing project involves two awesome things: Insects and Madagascar.

"Unique" doesn't begin to describe Madagascar. This giant island split from the African Continent over 160 million years ago, and over 90% of it's mammal and reptile species occur no where else in the world. Deforestation and erosion are critical threats to the island's ecosystems, and many native species are endangered.

Brian Fisher, one of the folks behind AntWeb, is leading a project to document the ant species of a high remote preserve. You might be wondering why you should care about ants in Madagascar. You may especially be wondering this because you have figured out that at some point later in this post I'm going to hit you up for a donation. I really like this statement from AntWeb that puts ants in context:

"At this moment, more than one thousand trillion ants are scurrying all over the Earth. If every human climbed aboard one side of a scale, and every ant crawled onto the other side, the scale would just about balance."

Ants probably move more earth and recycle more dead things yearly than a whole army of human undertakers with bulldozers ever could. Ants are a critical part of making the world's living systems function. The project description:

"Ants are the glue that hold forests together. But Madagascar's hotspots of biodiversity are vanishing, and along with them unknown species. An estimated 40 percent of the island's species, in fact, have already perished through human encroachment.

Pyramica hoplites stalks other insects in the leaf litter like a miniature jaguar. "If your sister goes to the corner for a glass of milk and never comes back, it's Pyramica that got her," says Fisher.

While ants aren't as popular as furry and feathery animals, the insects turn over forest soil, breakdown debris, disperse crucial nutrients and otherwise support an unimaginable number of species both up, down and across the food chain. The insects are also a growing resource for antimicrobial and antifungal compound discovery, as many ants manufacture such chemicals to ward off disease and even farm food.

I need to reach one of the last standing pristine forests, called the Kasijy, before nearby populations burn them down to raise cattle. Researchers have visited the remote site only a handful of times because it's a rugged, canyon-filled landscape resting on high blocks of limestone and sedimentary rock. Because Kasijy is so pristine, it also serves as a crucial data point of what Madagascar used to be like before the advent of modern civilization. The region and other forests are great places to understand the ongoing impacts of climate change on highly specialized ecosystems.

My expedition aims to:

Inventory Kasijy's untold new species and document their roles in a pristine natural ecosystem.

Understand the biodiversity patterns of Madagascar and resolve our "bioilliteracy" of the Kasijy forest.

Set up more robust conservation plans for the island.

Raise awareness of Madagascar's natural wonders and its ongoing plight."

There are 39 days left to fund this project–I hope you can spare a dollar or two to help a researcher out! Note that a large gift gets you acknowledged in any manuscripts published from this research.

And for a mere $5000, you can buy scientific immortality with your name, or the name of a friend or loved one, on one of Fisher's new species. Whatever you give, Fisher will not waste your money. When I was there, we jumped a freight train to get to a research site, and he seemed to live on rice, a little chicken, and a horrible tea made from the burnt leavings at the bottom of the rice pot.

February 28, 2012

Nature Is Vanishing from Kids' Books

One of my favorite things when my children were young was reading them Where The Wild Things Are, over and over, with lots of sound effects for the wild ruckus among the animals. But a new study, looking at Caldecott Prize winners from 1938 to 2008, suggests the natural world is vanishing from children's books. The study appears in February's Sociological Inquiry, and gets a write up in USA Today:

One of my favorite things when my children were young was reading them Where The Wild Things Are, over and over, with lots of sound effects for the wild ruckus among the animals. But a new study, looking at Caldecott Prize winners from 1938 to 2008, suggests the natural world is vanishing from children's books. The study appears in February's Sociological Inquiry, and gets a write up in USA Today:

•Early in the study period, built environments were the primary environments in about 35% of images. By the end of the study, they were primary environments about 55% of the time.

•Early in the study, natural environments were the primary environments about 40% of the time; by the end, roughly 25%.

Images of wild animals and domestic animals declined dramatically over time, says lead author Al Williams of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "The natural environment and wild animals have all but disappeared in these books."

Co-author Chris Podeschi of Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania says, "This is just one sample of children's books, but it suggests there may be a move away from the natural world as the population is increasingly isolated from these settings. This could translate into less concern about the environment."

Not to mention the terrible loss to parents and young children.

You can read the full study here.