Richard Conniff's Blog, page 90

July 19, 2012

Your Rx: A Two-Week Infection with Intestinal Worms

More evidence that the world we live in is just too sanitary and that we need to spend more of our lives rolling in the dirt.

Type 1 diabetes has inexplicably become epidemic in this country, occurring 10-20 times more commonly than it did a century ago.

Now new research suggests an explanation. Unlike us, people back then had intestinal worms to keep their immune systems in line. Hard to imagine that as a good thing, but read the press release:

Short-term infection with intestinal worms may provide long-term protection against type I diabetes (TID), suggests a study conducted by William Gause, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School. The research has been published in the journal Mucosal Immunology.

The incidence of TID—a form of the disease in which the body’s own immune cells attack the insulin-producing islet cells of the pancreas—is relatively low in developing countries. One explanation for this phenomenon is the prevalence of chronic intestinal worm infections, which dampen the self-aggressive T cells that cause diabetes and other autoimmune diseases. Understanding how T cells are tamed during worm infection could lead to new strategies to control these inflammatory diseases.

Dr. Gause’s team, including Pankaj Mishra, PhD, in his laboratory, and David Bleich, MD, now shows that a two-week infection with the intestinal worm H. polygyrus (cured using oral drugs) prompted T cells to produce the cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10, which acted independently to provide lasting protection against TID in mice. A similar approach using eggs from another parasitic worm, Trichuris suis, is currently being tested in clinical trials in patients with Crohn’s disease and multiple sclerosis. The studies presented in this paper now provide potential mechanisms explaining the potency of parasite-induced control of inflammatory diseases.

You can read more here. (And, as always, it mystifies me why the press release can’t include a simple link and citation for the research paper. Here is the abstract, anyway.)

July 8, 2012

Are Fake Forests Good Enough for Poor Folk?

The plaza in Bogota’s Cazucá neighborhood.

In today’s New York Times, architecture critic Michael Kimmelman looks at recent developments in Bogota, Colombia. I found this photograph–and the thinking behind it–highly disturbing. Here’s what Kimmelman writes:

City planners and government officials need to upgrade housing and infrastructure, without undermining homegrown energy and ground-up urbanism.

That’s partly the hope behind a 7,500-square-foot canopy [Giancarlo] Mazzanti has also designed over a concrete plaza in Cazucá, a truly forgotten place, perhaps the poorest and most violent slum in or around Bogotá, on a hillside not far from Bosa. A $614,000 project, paid mostly by Pies Descalzos, a private organization established by the singer Shakira, it came about after long negotiations with drug gangs that controlled the plaza, investing them in the plaza’s improvement, enlisting them in its maintenance. Mr. Mazzanti designed a field of large modules, dodecahedrons, made of green steel mesh and translucent panels, raised on slender steel tubes. The floating structure, perched along the side of a hill, suggests a thicket of trees, like umbrella pines, where there’s not a real tree in sight, a spectacle meant to be visible from far away.

The canopy can look like a lot of architecture for such a small project, but that’s partly its value: to put Cazucá on the map and create a de facto town square beside the school (made of shipping containers, serving a population in which a quarter of the children are malnourished, I was told by the school’s principal). Now children play soccer under the canopy and clean up the square every day, and there’s a vegetable garden with tomatoes and herbs.

What bugs me is that they could have put up real trees for far less money, and achieved the same results in terms of cleaning up the site, driving out the drug dealers, and giving people a public square where they could relax together. They might have had birds and the shifting of the leaves in an evening breeze. They would have had change with the seasons and the time of day, as well as with the passing of years.

There’s a widespread assumption that poor people (and nonwhites more generally) don’t value such things. They’re supposedly too busy trying to find jobs and feed their families. But surveys in recent years have demonstrated that they want these amenities as much as any other human being.

Instead, they get this instant faux-forest, which will inevitably look like hell, or require another $600,000 in repairs 10 years from now. It seems like a missed opportunity for Shakira, who has otherwise demonstrated admirable philanthropic instincts for improving education and other social services in her home country.

July 6, 2012

The Birth of Dinosaur Mania (A Glorious Enterprise–Conclusion)

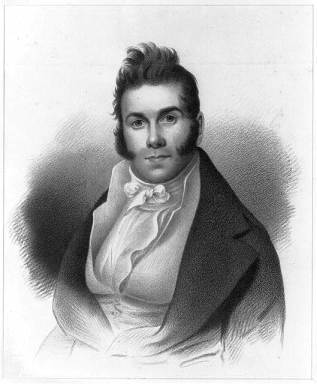

Leidy

The mid-nineteenth century was the end of the time when a naturalist’s scholarship could span the entire world, and that has always been a large part of the appeal of that era for modern readers. Not only were explorers from the Academy and other institutions going to new places and making great discoveries, but the average educated layperson could still understand what their work was all about. Professionalization would soon set in, obliging scientists to confine their research to ever more narrow specialties, often comprehensible only to a handful of like-minded experts around the world.

Joseph Leidy, who arrived at the Academy in 1842, managed to bridge both worlds. He was part of the new breed, a professional scientist, but still managed to work on everything from parasites to dinosaurs. He was the first to demonstrate that the parasitic disease trichinosis came from failing to adequately cook meat contaminated with roundworm larvae—and thus gets credit or blame for the next century or so of overcooked pork chops. He is also said to have been the first scientist to use his microscope to solve a murder, foreshadowing countless police procedurals and CSI episodes to come. (The suspect in the case contended that the blood on his shirt came from a chicken, not the murder victim. He confessed when Leidy demonstrated that the red cells contained no nucleus, as in humans.)

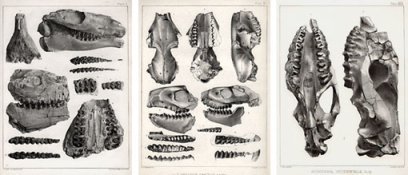

Leidy’s Ancient Fauna of Nebraska included an early camel (top left), some hog-like oreodonts (center), and an American rhinoceros (right).

But it was his fossils that really made Leidy famous. As collectors in the American West began sending him paleontological specimens, Leidy described a saber-toothed cat and a rhinoceros that had once roamed the Great Plains. His description of an ancient American camel led the War Department to create a U.S. Camel Corps in the 1850s, with animals imported from North Africa to transport equipment in the American Southwest. Leidy also demonstrated that horses had lived in America long before Spanish colonizers re-introduced them. (They disappeared the first time, he thought, because of climate change.) He “was discovering an entirely new world in the virgin fields of the American West,” write Peck and Stroud. “It was not possible to base his studies on those of European paleontologists because, according to the eminent scientist Henry Fairfield Osborn, ‘every specimen represented a new species or a new genus of a new family, and in some cases a new order.’”

Leidy and the Academy were the best available source of paleontological thinking when a British sculptor named Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins arrived in the United States in 1868. Hawkins had previously made concrete models of dinosaurs for London’s Crystal Palace in 1854. He liked to imagine what he called “the revivifying of the ancient world” and at a party held inside the mold for one of these models, the guests sang “The Jolly Old Beast/is not deceased/There’s life in him again.” But in truth, these dinosaurs were low, plodding, lifeless creatures, about as likely to induce wonder as the average lizard. (You can still see them on display at a park in London’s Sydenham Hill neighborhood.)

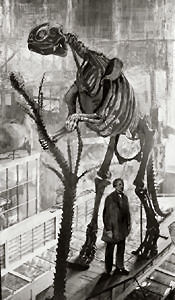

With Hadrosaurus foulkii, Hawkins had the opportunity to do it right. The scientific know-how came from Leidy and a young paleontologist named Edward Drinker Cope. (He who would later compete fiercely with Yale rival O.C. Marsh in the so-called “bone wars” to unearth the best Western dinosaur specimens.) Hawkins set to work rebuilding the animal, mounting plaster casts of the bones, and plaster reconstructions where needed, on an iron scaffolding. Because the dinosaur’s head was missing, the team modeled a replacement on the modern iguana, and painted it green. The finished animal, reassembled in just two months of feverish work, reared up overhead as if there were truly “life in him again” after 65 million years. Though Hawkins’ original is now lost, its innovative approach to fossil specimens continues to shape the way museums around the world display dinosaurs to this day.

POSTSCRIPT: At the end of their book A Glorious Enterprise, Peck and Stroud suggest that the work of discovery is not just romantic history. Scientists from the Academy continue to do research today everywhere from Venezuela’s Orinoco Delta to Lake Hovsgol in northern Mongolia. The work can seem obscure, and as in Thomas Say’s day, subject to ridicule or indifference from a society that tends to be more concerned with Hollywood celebrities. It’s also badly funded: In 2006, on the brink of financial collapse, the Academy caused a flurry of protest when it sold off more than 18,000 mineral specimens to keep itself alive. But we ignore this work at our considerable peril. The Academy’s naturalists had quietly shaped America’s past (and its ideas about its past). Their counterparts today have the power to shape our future.

July 3, 2012

The Place of the Skulls–An (In)Glorious Enterprise–Part 4

Skull Man Morton

The 1840s also saw the Academy achieve its most disturbing and unsavory influence on American life. According to one interpretation, Samuel G. Morton, a Philadelphia Quaker, physician, and naturalist at the Academy, was the founder of physical anthropology, the science of carefully measuring the physiological differences among human groups. But the other interpretation, championed by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould in the 1970s, characterized Morton as the father of scientific racism.

Morton studied human skulls and eventually accumulated 1000 of them from around the world, a collection his friends proudly described as “the American Golgotha.” (The name of the hill on which Christ was crucified meant literally “place of the skull”). He measured brain capacity by filling the inverted skulls with white mustard seed, at first, and later, for greater uniformity, with No. 8 shot, a methodology considered remarkably objective and scientific for its time. At Morton’s death in 1851, a New York newspaper remarked that “probably no scientific man in America enjoyed a higher reputation among scholars throughout the world.”

But Morton believed he could characterize human races by the capacity of their skulls, with a bigger skull meaning a bigger brain, a bigger brain meaning greater intellectual ability, and the biggest brains naturally belonging to Europeans. On reviewing Morton’s work, Gould acknowledged that he could find “no indication of fraud or conscious manipulation.” But he called it “a patchwork of assumption and finagling, controlled, probably unconsciously,” by the urge to put “his folks on top, slaves on the bottom.” A new study published last year disputed the charge of finagling and found that most of Gould’s own criticisms “are poorly supported or falsified.” But no one denies that Morton was a racist.

By seeming to provide a scientific basis for prejudice, Morton handed ammunition to bigots in the vicious racial politics before the Civil War. One Morton disciple, the Alabama physician Josiah Clark Nott, was endowed with an especially polemical frame of mind and a lynch-mob way with words. He distilled Morton’s research into lectures on what he called “niggerology.” A slave-owner himself, he believed, like Morton, that whites and blacks originated as separate species.

Nott piously declared that he loathed slavery in the abstract. But as a practical reality, it was a kind of public service, enabling a lesser human species to attain “their highest civilization.” He added that “the Negroes of the South are now … the most contented population of the earth.”

Rather than distancing himself from such twisted reasoning, Morton wrote of his “great pleasure and instruction” as Nott advanced his ideas where he himself had held back.

Losing Audubon (A Glorious Enterprise, part 3)

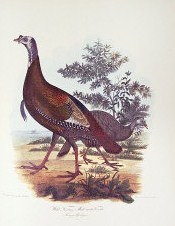

Wild turkey by Wilson

Another early member of the Academy, the Scottish immigrant Alexander Wilson, launched the scientific study of birds in America with his American Ornithology, the ninth and final volume being published in 1814, a year after his death.

Ironically, though, that connection also caused the Academy to reject John James Audubon when he showed up at a meeting 10 years later seeking support for what would become the most celebrated work of American natural history ever published.

Audubon was a colorful frontier character and no diplomat. Otherwise, he would have known that George Ord, president of the Academy, had been Wilson’s closest friend and had functioned as his literary executor. Instead, Audubon seems to have clumsily disparaged Wilson, as a way of promoting the superiority of his own work.

Ord

Ord, who came from a prosperous rope manufacturing family, was a quarrelsome, condescending figure. He made life difficult for everyone associated with the Academy in those years, and particularly for Audubon.

“Incensed by the newcomer’s brash and tactless remarks, he rose to Wilson’s defense, challenging Audubon’s scientific credentials and integrity,” Peck and Stroud write, in A Glorious Enterprise. “By the end of the meeting, it was clear that any possibility of the Academy supporting Audubon’s project had vanished.”

Thus Audubon had to turn to Europe for the triumphant publication of his Birds of America.

June 27, 2012

A Democratic American Science (A Glorious Enterprise–Part 2)

Peale was a showman for his museum

Philadelphia was already home, in 1812, to the American Philosophical Society, dedicated by Benjamin Franklin to all studies “that let Light into the Nature of Things, tend to increase the Power of Man over Matter, and multiply the Conveniencies or Pleasures of Life.” The Philadelphia Museum was also thriving then, with the entrepreneurial artist Charles Willson Peale displaying portraits of great American patriots and specimens of great American wildlife side by side.

The founders of the Academy meant to set themselves apart by focusing exclusively on the natural world, not culture or the arts. And they wanted to do scholarly work, avoiding the kind of promotional hoopla Peale sometimes indulged in to attract paying customers. The Academy was also determined to be democratic. Whereas the American Philosophical Society drew its members from the elite (including 15 of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence), the Academy’s founders were local businessmen and immigrants drawn together by a single idea: “We are lovers of science.” They resolved that their organization would be “perpetually exclusive of political, religious and national partialities, antipathies, preventions and prejudices.” This was no doubt wishful thinking. As at most such institutions then, the Academy’s membership was entirely white and male, until the widow of one of the founders was admitted in 1841. And even brotherhood would prove elusive. (One founder was soon describing another as a “hot headed eccentric Irishman” and “some what crack brained.”)

Thomas Say

But the founders of the Academy were at least sincere in wanting to develop a proper American science for understanding and describing the riches of the still largely unexplored continent. “The time will arrive,” wrote Thomas Say, the intellectual force behind the Academy in its early years, “when we shall no longer be indebted to the men of foreign countries, for a knowledge of any of the products of our own soil, or for our opinions in science.” Say himself would become the father of American entomology, describing roughly 1400 insect species in his lifetime, including many of critical economic importance in agriculture.

Say would also become the first trained naturalist to visit the American West, as chief scientist on the Long Expedition of 1819-20, and he provided the first descriptions of many now beloved species there, from the swift fox to the Lazuli bunting (see “What Is Out There?” American History, October 2010)—and also of many insects. At one point, Say recounted how he was seated with a Kansa chieftain, “in the presence of several hundred of his people assembled to view the arms, equipment, and appearance of the party,” when a darkling beetle came scurrying out from among the feet of the crowd. Diplomatic dignity wrestled briefly with the passion for species. Then Say went plunging after the beetle and impaled it on a pin, for which the astonished Kansa admiringly dubbed him a medicine man.

Back home in Philadelphia, studying insects was more likely to attract “the ridicule of the inconsiderate,” as Say ruefully admitted. But another of his discoveries, the mosquito species Anopheles quadrimaculatus, would turn out, long after his death, to be the chief carrier of “ague,” or malaria. And identifying this culprit would become the key to eliminating a plague that routinely killed Americans from the Gulf Coast as far north as Boston and the Great Lakes.

A Glorious Enterprise–Part 1

The Philadelphia Hadrosaur

Though some of its counterparts are bigger and better known, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia is the oldest natural history institution in the New World. It is currently marking its 200th anniversary with an exhibition “The Nature of Discovery,” on display through next March. Its colorful history is also the subject of a lavishly illustrated new book, A Glorious Enterprise (University of Pennsylvania Press), co-authored by Peck and historian Patricia Tyson Stroud, with photographs by Rosamund Purcell. And I am marking the occasion with this article on some of the Academy’s accomplishments.

In November 1868, without fanfare or even much thought to how the public might respond, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia opened its doors on one of the most sensational museum displays ever. It was the world’s first nearly-complete dinosaur skeleton, discovered 10 years earlier in Haddonfield, New Jersey, and it was the first life-like dinosaur mount anywhere.

Hadrosaurus foulkii stood on its hind legs and towered more than two stories tall. So many people showed up to gape at this astonishing monster that the Academy’s scientists, distracted from their studies, complained about “the excessive clouds of dust produced by the moving crowds,” not to mention broken glass and battered woodwork. It was the beginning of dinosaur-mania in North America, and it changed the way museums everywhere would re-create the lost world of extinct species.

The Academy might have preferred to go about its work more quietly. But it was by then accustomed to playing an important part in the history of the nation, and of science. Philadelphia considered itself “the Athens of America” in 1812, the year that a small band of naturalists met at the home of a local apothecary to found the Academy. That it happened in the war year 1812 was “no coincidence,” says Robert Peck, a curator at the Academy. “The United States was declaring our independence politically and economically again, and we were declaring our intellectual independence for the first time.” Founding the Academy meant founding a democratic American science, the equal of its old world counterparts but without the elitist trappings. The Academy would also have its own journal, so our scientists “would not have to run to Europe to have their discoveries vetted.” It would be intellectually rigorous, but also inexpensively printed, so working people like the founders themselves could afford to read it.

In the decades that followed, the Academy would help shape the character of the American nation. Its scientists helped plan and carry out the early exploration of the American West, founded and largely established the science of ornithology in America, served as the seed bed (albeit reluctantly) for Robert Owen’s utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, became the center of scientific racism in the decades leading up to the Civil War, and fought one side in the brutal dinosaur “bone wars” of the late nineteenth century. It counted Thomas Jefferson and Charles Darwin as corresponding members, was frequented by Edgar Allan Poe, and in the twentieth century gave the world that dashing British spy James Bond–or at least his namesake. (Novelist Ian Fleming, a weekend birder in Jamaica, borrowed the name from the author of the field guide Birds of the West Indies, because it sounded suitably Anglo-Saxon. He later gave a copy of one of his books to the original James Bond, an ornithologist at the Academy, signed, “To the real James Bond, from the thief of his identity.”)

June 26, 2012

Unlikely Friendship?

I was just loving this photo from Emilie Genty. Then those damned Facebook commenters had to point out that the toad is dead and probably intended as dinner. Alternatively, there is a youtube video of a chimp using a toad as a sex toy.

Either way, probably a good thing National Geographic isn’t showing the next few frames in this series. Photographer Genty, by the way, is a post-doc at the University of St. Andrews, researching vocal and gestural communication among bonobo chimps.

June 25, 2012

David Douglas

Today’s the birthday of the pioneering Scottish botanist David Douglas (1799-1834), from whom the Douglas fir gets its common name.

Today’s the birthday of the pioneering Scottish botanist David Douglas (1799-1834), from whom the Douglas fir gets its common name.

On an 1824 expedition to North America, he described the sitka spruce, Ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and many other species, at one point writing home to his sponsor, “You will think I manufacture pines at my pleasure.”

On a later expedition to Hawaii, he died, age 35, when he fell into a pit dug by the islanders to trap wild cattle. He was trapped with a bull that also fell into the pit and it gored him to death.

June 20, 2012

A Sign of Stupidity

I saw this billboard recently while driving in Northern Virginia. You would think that someone in the extermination business would know that the animal in the middle (“…ugh!”) is not in fact a “bug” at all.

It’s a spider. (“Lemme see, oh yeah, eight legs.”)

And spiders generally do a better job than exterminators at getting rid of insect pests.

Maybe that’s why they want to kill them?