Richard Conniff's Blog, page 94

February 28, 2012

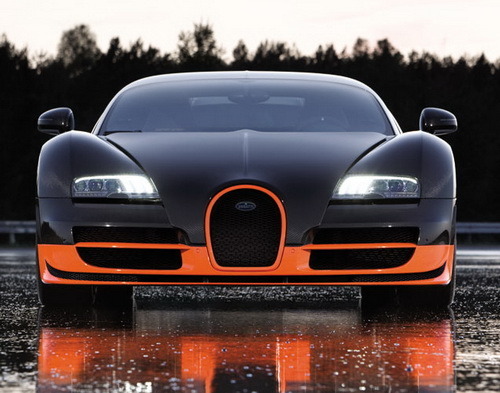

Among the One Percent, Look Twice Before Crossing

Shiny Cars, Scary Drivers

For cynics, this might come as unsurprising science. But a new study shows that as social status rises, so does the propensity to commit unethical acts, like lying in a negotiation, cheating, stealing, and breaking the law while behind the wheel. The study fits a long line of research by Dacher Keltner at the University of California in Berkeley.

I've written in the past about his "Cookie Monster" experiment for The New York Times. For the new study, published Monday on PNAS:

Observers stood near the intersection, coded the

status of approaching vehicles, and recorded whether the driver

cut off other vehicles by crossing the intersection before waiting

their turn, a behavior that defies the California Vehicle Code. In

the present study, 12.4% of drivers cut in front of other vehicles.

But drivers of top status cars cut off other cars almost 30% of time, versus less than 10% for the lowest-status cars.

It was even worse for pedestrians: Top status drivers cut off pedestrians 45% of the time, versus close to zero for the lowest-status drivers.

The study attributes the effect to multiple factors:

Upper-class individuals' relative independence from others and increased privacy in their professions (3) may provide fewer structural constraints and decreased

perceptions of risk associated with committing unethical acts (8). The availability of resources to deal with the downstream costs of unethical behavior may increase the likelihood of such acts among the upper class. In addition, independent self-construals among the upper class (22) may shape feelings of entitlement

and inattention to the consequences of one's actions on others (23). A reduced concern for others' evaluations (24) and increased goal-focus (25) could further instigate unethical tendencies among upper-class individuals. Together, these factors may give rise to a set of culturally shared norms among upperclass

individuals that facilitates unethical behavior.

The bottom line: If there's a Mercedes or Escalade in the neighborhood, stand back from the curb and pray, while also watching your wallet.

Let's call it "the Lizzie Grubman effect," for the wealthy publicist who allegedly yelled "Fuck you, white trash" before backing her Mercedes into a crowd of pedestrians outside a Long Island nightclub. (And true to the study's theory about "downstream costs," she got off with 37 days in jail.)

"High social class predicts increased unethical behavior," by Paul K. Piff, Daniel M. Stancato, Stéphane Côté, Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, and Dacher Keltner

February 27, 2012

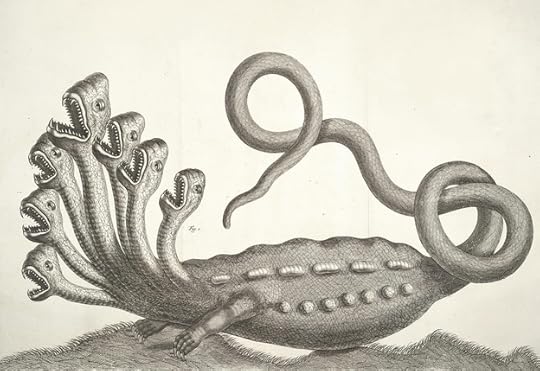

The Jabberwocky World

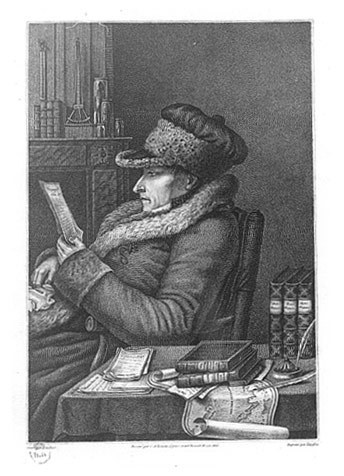

The March-April issue of Audubon magazine features this lovely illustration of a hydra, a monster from the Classical imagination, together with an excerpt from The Species Seekers, about the beginning of the age of discovery:

The March-April issue of Audubon magazine features this lovely illustration of a hydra, a monster from the Classical imagination, together with an excerpt from The Species Seekers, about the beginning of the age of discovery:

At the start, naturalists knew no more than a few thousand species, and often had the basic facts wrong. Even educated people still inhabited a jabberwocky world in which monsters abounded, and one species could slide uncertainly into another. Our own ancestors, just eight or ten generations ago, still thought that dog-headed humans lived in distant lands, probably based on early descriptions of baboons. When the fossil skeleton of a giant salamander turned up, a learned Swiss physician identified it as a sinner drowned in Noah's Flood. Naturalists then could not even clearly distinguish some plants from animals and passionately debated whether one could transform into the other, and back again. (It's a measure of the state of knowledge then that they thought of themselves simply as naturalists or "natural philosophers." The words "scientist" and "biologist" did not yet exist.)

That would all change, as a small band of explorers set out to break through the mystery and confusion. The great age of discovery about the natural world was a period of less than 200 years, from the eighteenth century into the twentieth. It got its start in 1735, when the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus invented a system for identifying and classifying species. He was a charismatic teacher, both ribald and full of religious fervor for the wonders of the natural world. His words inspired 19 of his own students to undertake voyages of exploration. Half of these "apostles," as he called them, would die overseas in the service of his mission. Explorers from other nations, also inspired by Linnaeus, soon followed, taking the hunt for new species to the farthest ends of the Earth. They made the discovery of species one of the most important and enduring achievements of the colonial era.That word "discovery" may stick momentarily in the modern reader's craw. Local people had often known many of these "new" species for thousands of years and in far more intimate detail than any newcomer could hope to achieve. But done properly, the process of collecting a species and describing it in scientific terms made that knowledge available everywhere. Making it available in Europe was, to be sure, the primary objective. But in the process, the species seekers introduced humanity for the first time to our fellow travelers on this planet, from beetles to blue-footed boobies. And gradually we stumbled from the security of a world centered on our species, created for our comfort and salvation, to a world in which we are one among many species.

It would be difficult to overstate how profoundly the species seekers changed the world along the way. Many of us are alive today, for instance, because naturalists identified obscure species that later turned out to cause malaria, yellow fever, typhus, and other epidemic diseases. (This is one of the recurring lessons from the history of species discovery: Useless knowledge has an insidious way of leading people in useful directions. Many mothers would despair, for instance, to have a child make a career out of the study of Chinese horseshoe bats of the genus Rhinolophus. But the subject took on global importance when these bats turned out to be the source of SARS, or sudden acute respiratory syndrome, which threatened to become pandemic.)

The discovery of species also shifted the foundations of knowledge and belief. Though early species seekers typically set out to glorify God by celebrating his Creation, the paradoxical outcome of their work was to cast doubt in many minds on the very existence of God. Species that seemed insignificant in themselves would raise disturbing questions about human origins, the age of the planet, the nature of sex, the meaning of races and species, the evolution of social behaviors, and endlessly onward. When we look in the mirror today, we can hardly help but see what the species seekers showed us.

February 23, 2012

Insect Paranoia

I was visiting author and entomologist May Berenbaum recently at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, and her collection of old insecticides caught my eye

Feds Bust U.S. Rhino Horn Smuggling Ring

The L.A. Times reports on the arrests today of a ring of U.S.-based rhinoceros horn smugglers. Here's an excerpt:

The L.A. Times reports on the arrests today of a ring of U.S.-based rhinoceros horn smugglers. Here's an excerpt:

The arrests and seizures sprang from an 18-month investigation, called Operation Crash, so-named because "crash" is another name for a herd of rhinos, said Edward Grace, deputy chief of law enforcement for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The undercover operation was forced into the open when accused trafficker Wade Steffen of Hico, Texas, and his wife and mother were stopped by Transportation Security Administration officials at Long Beach Airport on Feb. 9 with $337,000 in their carry-on luggage, authorities said. A TSA officer found $20,000 in $100-bill bundles in Molly Steffen's purse. "That money is not mine," Molly Steffen said, according to a federal affidavit. "I assume my husband put it in my purse."

Merrily Steffen, the mother, allowed officers to view the pictures on the memory card of a camera she was carrying, according to the affidavit. It contained images of "stacks of $100 bills bound with rubber bands" and "rhinoceros horns being weighed on scales."

Wade Steffen is incarcerated in Texas. Neither his wife nor his mother was arrested.

During their probe, wildlife officials had intercepted at least 18 shipments of rhino horns from the Steffen family and the owner of a Missouri auction house that trades in live and stuffed exotic animals, court records show. The packages were opened, the horns were identified by scientists and the items were repackaged and sent along to Kha's export business or Nguyen's nail shop, then presumably smuggled out of the country, according to law enforcement sources and court records.

Investigators tracked the movements of hundreds of thousands of dollars though bank wire transfers, including to accounts in China, and travel records of suspects who flew between Los Angeles and Asia, as well as between California, Texas and Missouri.

Read the full article here. The US Fish & Wildlife press release follows after the break:

WASHINGTON – Seven people have been arrested on charges of trafficking in endangered black rhinoceros horn over the past week in Los Angeles, Newark, N.J., and New York, the Department of Justice and Department of the Interior today announced. Special agents of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) made the arrests and have executed search warrants in five different states as part of "Operation Crash," a multi-agency effort to investigate and prosecute those involved in the black market trade of endangered rhinoceros horn.

In Los Angeles, Jin Zhao Feng, a Chinese national who allegedly oversaw the shipment of at least dozens of rhino horns from the United States to China, was arrested last night. Last weekend, members of an alleged U.S.-based trafficking ring that supplied rhino horns to Feng were arrested after being charged with conspiracy and violations of the Lacey Act and the Endangered Species Act for purchasing rhino horns from various suppliers in the U.S. Charges were filed against Jimmy Kha, the owner of Win Lee Corporation; his son Felix Kha; and Mai Nguyen, the owner of a nail salon where packages containing rhinoceros horns were being mailed. One of the alleged suppliers, Wade Steffen, was arrested in Hico, Texas, and charged in Los Angeles. According to a criminal complaint filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles, the Khas began receiving packages from Steffen and another supplier in 2010. Seventeen packages were opened under federal search warrants and 37 rhinoceros horns were found.

A search of Steffen's luggage at the Long Beach Airport in California on Feb. 9, 2012, turned up $337,000 in cash. In additional searches conducted by FWS and ICE, agents found rhinoceros horns, cash, bars of gold, diamonds and Rolex watches. Approximately $1 million in cash was seized and another $1 million seized in gold ingots.

"The rhino is an animal of prehistoric origin that is facing possible extinction because of an illegal trade for its horns on the black market that is driven by greed," said Ignacia S. Moreno, Assistant Attorney General for the Environment and Natural Resources Division of the Department of Justice. "The rhino is protected under both U.S. and international law, and we are taking aggressive action to protect the rhino by investigating and vigorously prosecuting those who are engaged in this brutal trade."

In New Jersey, Amir Even-Ezra was arrested Saturday, Feb. 18, 2012, on a felony trafficking charge in violation of the Lacey Act after purchasing rhino horns from an individual from New York at a service station off of the New Jersey Turnpike. Even-Ezra allegedly brought a scale for weighing the horns and envelopes of cash to the meeting, which was brokered by an individual outside of the United States.

In U.S. District Court in Manhattan, antiques expert David Hausman was also charged with illegally trafficking rhinoceros horns and with creating false documents to conceal the illegal nature of the transaction, both in violation of the Lacey Act. Hausman allegedly purchased a black rhinoceros mount (a taxidermied head of a rhinoceros) from an undercover officer in Illinois and was later observed sawing off the horns in a motel parking lot. Rhino horns were found in a search conducted on Saturday, Feb. 18, 2012, following his arrest.

"Rhino horn traffickers continue to fuel the illegal demand for horn, demand that has led to hundreds of rhino deaths and put the white and black rhino in danger of extinction in the wild," said U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe. "These arrests have dealt a serious blow to rhino horn smuggling, but represent only the beginning of a significant crackdown on this illegal trade."

"The illegal trade in endangered wildlife robs the world of these magnificent creatures in their natural habitat," said ICE Director John Morton. "This case is a reflection of our commitment to ensuring that our children and grandchildren are not deprived by criminals whose only goal is to make a quick buck at the expense of these innocent creatures."

Rhinoceros are an herbivore species of prehistoric origin and one of the largest remaining mega-fauna on earth. All species of rhinoceros are protected under U.S. and international law. All black rhinoceros species are endangered. Rhino horns are composed of keratin, the same type of protein that makes up hair and fingernails. Rhinoceros horn is a highly valued and sought-after commodity despite the fact that international trade has been largely banned since 1976. The demand for rhinoceros horn, which is used by some cultures for ornamental carvings, good luck charms or alleged medicinal purposes, has resulted in a thriving black market – a market that has escalated in recent years in both volume and per-unit profit.

If convicted, maximum penalties under these charges are up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine for conspiracy; five years in prison and a $250,000 fine for Lacey Act violations; and up to one year in prison and a $100,000 fine for violations of the Endangered Species Act.

Operation Crash (a "crash" is the term for a herd of rhinoceros) is a continuing investigation by the Department of Justice and the Department of the Interior FWS, with assistance from other federal and local law enforcement agencies including ICE and the Internal Revenue Service. The investigation is being led by the Special Investigations Unit of the FWS Office of Law Enforcement and involves a task force of agents focused on rhino trafficking.

A criminal complaint is a charge based on probable cause allegations. A defendant is presumed innocent unless and until convicted.

The criminal prosecution is being handled by the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Central District of California, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the District of New Jersey, the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York and the Environmental Crimes Section of the U.S. Department of Justice's Environment and Natural Resources Division, with assistance from the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Western District of Missouri.

Many Years of Thought????

I can't quite get over this pair of emails I received yesterday from a publicist, especially the idea that someone claiming to have spent "many years of thought and a decade of researching and writing" would somehow end up putting his byline on someone else's work.

Here's the "Oops" email:

On Wed, Feb 22, 2012 at 4:04 PM, Liz Mensching wrote:

> Please disregard the message below, sent earlier today. It contains a copyrighted article by Michael Shermer from the Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2008. I'm sorry for any inconvenience.

>

The original email had arrived a few minutes earlier (bold face added, and I mean that literally. The metaphorical boldface was definitely there in the original message):

> ORIGINAL MESSAGE

>

> The following article is ready to run as is or with edits. The author, Oliver Deehan, is available for interview opportunities and copies of his book, To Find the Way of Love, are available upon request.

>

> Thanks for your time,

> Liz Mensching

> lmensching@bohlsengroup.com | 317.602.7137

>

>

> Becoming a Type 1 Civilization

> By Oliver Deehan

>

> Our civilization is fast approaching a tipping point. Humans will have to make the transition from nonrenewable fossil fuels as the primary source of energy to renewable sources that will allow us to flourish in the future. Failure to make that transformation will doom us to the endless political machinations and economic conflicts that have plagued civilization for the last half-millennium.

>

> We need new technologies to be sure, but without evolved political and economic systems, we cannot become what we must. And what is that? A Type 1 civilization. Let me explain.

>

> In a 1964 article on searching for extraterrestrial civilizations, the Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardeshev suggested using radio telescopes to detect energy signals from other solar systems in which there might be three levels of advancement. Type 1 civilizations can harness all of the energy of its home planet. Type 2 can harness all of the power of its sun, and Type 3 can master the energy from its entire galaxy.

>

> Based on our energy efficiency at the time, in 1973 the astronomer Carl Sagan estimated that Earth represented a Type 0.7, although more current estimations put us at 0.72. As the Kardashevian scale is logarithmic, where any increase in power consumption requires a huge leap in power production, we have a ways to go before reaching the desirable 1.0.

>

> Here a few characteristics of a true Type 1 society:

>

> * Improved energy efficiency by making the transition from nonrenewable fossil fuels to renewable energy sources

> * Worldwide wireless Internet access. All knowledge is digitized and available to everyone

> * A completely global economy, where anyone can trade without interference from states or governments

>

> We have a proven track record of achieving remarkable scientific solutions to problems that threaten our survival. We now have the opportunity to live in a win-win world and become a Type 1 civilization by spreading liberal democracy and free trade. That is change we can believe in.

>

> About the author

>

> Oliver Deehan was a Navy fighter pilot, sailor, skier, and executive who built and administered hospitals. For the last twenty years, his concerns have been about human relationships and how the importance given to the individual has superseded the importance of relationships, with self-love trumping our love of others. This resulted in many years of thought and a decade of researching and writing the book, To Find the Way of Love.

Here is the link to Michael Shermer's original article in the L.A. Times.

February 21, 2012

The Collecting Life

Too often, people send me names of naturalists to be added to the Wall of the Dead. (Josh Nove is the latest, added this morning.) But this time, a son has written to ask that his father be removed from the list. Here's the original entry:

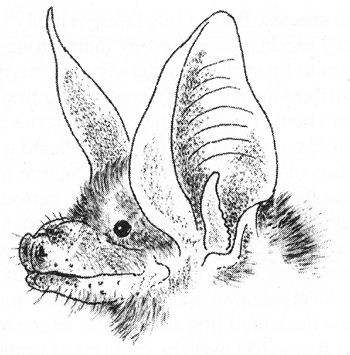

Van Gelder, Richard G. (1928-1994), prominent mammalogist with the American Museum of Natural History, died, age 65, either from acute monocytic leukemia or, as friends recall, from falciparium malaria acquired in Kenya.

But Gordon Van Gelder writes: "I'm emailing you to thank you for listing him, but I think he—like his idol, Charles Darwin—doesn't belong on the list." The list memorializes naturalists who died in the course of their field research to discover and describe new species. But Richard Van Gelder "did in fact die at home from acute monocytic leukemia. It is true that he contracted malaria during one of his trips to Kenya and it recurred several times, [but] that was in the 1980s."

Richard is, however, clearly worth remembering in a context other than the Wall of the Dead. Among his many achievements, he discovered a new species of vesper bat, commonly known as Van Gelder's Bat.

Richard is, however, clearly worth remembering in a context other than the Wall of the Dead. Among his many achievements, he discovered a new species of vesper bat, commonly known as Van Gelder's Bat.

Gordon kindly also sent along a description of the collecting life from his father's unpublished memoir:

Mammal collecting is perhaps the most arduous of all the fields. The entomologist can set up his nets and lights and run through the fields like my old friend "Madam Butterfly." When they catch something they pop it into a killing-jar and when it is dead they lay it out between soft cellulose sheets and take it home. The rest of the preparation, mounting on pins, labelling, or making microscope slids of the specimen is done by their technicians. The herpetologist goes around turning over logs and grabbing snakes and lizards or pops them with his .22 dust shot. When he has a bag full he plunks them into alcohol and throws in a label.

But mammalogists do most of their preparation in the field, and they also deal with some pretty big critters. Each one has to be measured and weighed, and we usually pick them over for fleas and ticks (for our entomologist colleagues), and then we have to skin them and stuff them. We don't do taxidermy, but we make something called a study skin, that looks like some of the fluffy toys they sell in F.A.O. Schwarz. Then the guts have to be scraped out of the carcass (and maybe you'll pickle a few goodies like the ovaries or testes), and then most of th eflesh has to be cut from the skeleton so that it wil dry.

With experience, a good mammalogist can whip up a mouse study skin, from trap to drying board, in about 12 to 15 minutes. The best I have ever done was 65 mice in one day—and a day doesn't mean just the skinning and stuffing part. It also includes running your traps in the morning to pick up the catch and going out in the afternoon to re-bait them and maybe set some new ones.

Then, when dusk comes, you set up your bat nets, which are fine nylon nets that are successful in trapping bats, and stand by with your shotgun to pot a few that might be too high for the nets. When it is good and dark, you find it pretty profitable to go out with your shotgun and a headlamp potting mice and small carnivores as they eye-shine from your light. Around midnight you might be feeling a bit bushed, so you head back to camp, and if it is warm and some specimens might not keep until morning, you spend another hour or two putting up your evening catch, write up your notes, and sack out for a hearty couple of hours until sunrise when you have to get to the traps before the sun bloats your specimens?

Sleep?—forget it, when the mice are running you get all you can.

February 20, 2012

Did George Give Aid and Comfort to the Enemy?

In 1782, General George Washington sent a dozen men with wagons and tools north from West Point. What was their mission?

In 1782, General George Washington sent a dozen men with wagons and tools north from West Point. What was their mission?

1. Collect dinosaur fossils.

2. Build a bridge over the Fish Kill River.

3. Dig up mastodon bones.

4. Capture, hang, and bury the traitor Benedict Arnold.

And the answer is:

In the eighteenth-century, when natural history was the most exciting thing in the scientific world, it was common for even the busiest and most powerful men and women to take time to collect a new species, or to reach across enemy lines in joint pursuit of some precious fossil.

The American Revolution had already begun in 1775, for instance, when Benjamin Franklin instructed American warships not to interfere with Capt. James Cook as he was returning on HMS Resolution from his second voyage of discovery around the world.

And the war had not quite ended in 1782, when General George Washington lent a dozen men with wagons and tools to help an enemy officer excavate a mastodon in the Hudson River Valley.

It started two years earlier, after a ditch-digger turned up teeth of the creature than known as the "incognitum" or "mammoth" in New Windsor, N.Y. Gen. Washington made the 10-mile trip from the Continental Army's winter encampment at West Point. He noted that these new finds matched a tooth in his private collection at home retrieved from Big Bone Lick in Kentucky. Then in 1782, as negotiations to end the war proceeded, Gen. Washington lent a dozen men with wagons and tools to help an enemy officer, Dr. Christian Friedrich Michaelis, physician-general to the Hessian mercenaries employed by the British, in an unsuccessful attempt to excavate the rest of the bones.

The British would later extend the same courtesy to their French enemies. When a ship fell into their hands carrying the natural history collection of an expedition by LaPérouse, Sir Joseph Banks declared, "I have never heard of any declaration of war between the philosophers of England and the philosophers of France. These French collections must go to the French museum, not the British."

And how did the French behave, in turn? Well, read chapter five in The Species Seekers where I talk about how the French anatomist Georges Cuvier got the specimens he used in describing–and naming–the mastodon.

February 17, 2012

When the Urge to Discover Outlives the Ability

In the course of writing The Species Seekers, it often struck me how powerfully biological explorers felt the urge to discover, to delight, and to categorize. To my regret, I could not find room for the following anecdote, told by an elderly naturalist who still felt that urge, but no longer had the means to gratify it, near the end of a life spent sorting out the minute differences among related insect species.

In Science magazine for November 4 1932, entomologist Leland O. Howard wrote that he could no longer read or work at the microscope. Instead, "I have been interesting myself by watching my eye-spots—those fragile things that float before one's eyes, apparently in space. I have recognized three species of insects, two plainly, and the third rather dimly."

In Science magazine for November 4 1932, entomologist Leland O. Howard wrote that he could no longer read or work at the microscope. Instead, "I have been interesting myself by watching my eye-spots—those fragile things that float before one's eyes, apparently in space. I have recognized three species of insects, two plainly, and the third rather dimly."

One of them had "spotted wings and apparently the venation of a trypetid fly." Another looked like the pupa of Culex pipiens. ("I can see the respiratory trumpets on the thorax and it is plainly Culicine—not Anopheline. ")

"Other biologists who have misused their eyes (as I have) may amuse themselves by classifying their eyespots…"

In a subsequent issue of Science, a retired corporate executive replied in the same fanciful spirit, "I have, in one of my eyes, a cross between a lizard and a turtle which suddenly jumps aside when I try to pin it down for Latin names."

February 16, 2012

Victory to the Shaggy

Carpet shark swallows a bamboo shark whole (courtesy Tom Mannering)

We like to believe that victory belongs to the sleek and the strong. But sometimes being shaggy and obscure works better. Daniela Ceccarelli and David Williamson, from the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, were doing research on the Great Barrier Reef when they spotted the spectacle of one shark swallowing another whole.

Bamboo sharks, looking as slick and smooth as an Apple product, forage for food by nosing into nooks and crannies along the bottom. Carpet sharks, by contrast, are shaggy, camouflaged creatures that lie on the bottom and do nothing. (Think of them as Microsoft products.)

But when dinner comes to them, they snap it up.

February 13, 2012

Did Pretty Shells Cost Them a Continent?

Citizen Baudin

In 1800, two French ships re-named the Géographe and the Naturaliste set out from Le Havre, France, under the command of Capt. Nicolas Baudin, with 23 scientists aboard in addition to crew. They were bound for the unknown coast of Australia. The British, fearing that the French had colonial ambitions there, soon sent out a rival expedition under the command of Matthew Flinders.

Baudin's expedition sent home a spectacular assortment of species, including 144 new birds, surveyed parts of the coast of Australia, and eventually made peaceful contact with Flinders in what is now Encounter Bay. But his company bickered childishly, according to Encountering Terra Australis, a history of the rival voyages. In the past, such voyages had been under the command of aristocrats, and old attitudes persisted after the French Revolution. Baudin's naval officers were indignant about serving under a captain of humble social background.

The scientists meanwhile squabbled about access to resources and about getting proper credit for

Peron

their work. At one point, zoologist François Péron presented himself to Baudin dripping with blood, from a fight with the ship's surgeon over which of them should get the "glory" of dissecting a shark. Péron lost and whined that the surgeon had stolen the shark's heart. Not content to be merely a zoologist, Péron also played at being a spy, making a crude survey of British defenses at Port Jackson (now Sydney) and urging French authorities to destroy the colony as a way of snuffing out British imperial ambitions in Australia.

Citizen Baudin didn't suffer from the common tendency of naval officers to regard scientists as a nuisance (though in this case it would have been understandable); he was a naturalist himself. But instead of capitalizing on their good fortune, one naturalist complained that Baudin "would prefer to discover a new mollusk than a new landmass." And at Encounter Bay, a disgruntled French officer told the British "if we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies at Van Diemen's Land [now Tasmania], you would not have discovered the south coast before us."

###

Find out more in chapter three of The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth.