Richard Conniff's Blog, page 91

June 19, 2012

Murder and the Immortal Exine

Pollen (photo by Endless Forms Most Beautiful)

The first time police used pollen to solve a crime was in Austria in 1959. A forensic scientist studying the mud on a murder suspect’s boot found what turned out to be a 20-million-year-old pollen grain from a hickory tree. That species no longer grew in Austria then. But investigators were able to locate a Miocene sediment outcrop on the Danube River, from which such a pollen grain could have become recycled into the environment.

“We know you killed him,” they told the murder suspect, in the best police procedural fashion, “and we know where.” Then they took him to the outcrop. The suspect was so unnerved that he led them straight to the victim’s grave.

Pollen analysis is still surprisingly rare in U.S. courtrooms, though such cases have made it commonplace in some other countries. Even in the “CSI” era, Americans tend not to think about it much, other than as a cause of hay fever. Certainly no one grows up wanting to be a pollen scientist. Even experts in the field have a curious tendency to explain that they came to pollen only by accident and somehow got hooked. It’s as if they fear that outsiders might otherwise think them congenitally dull.

But for an impressive, if less sensational, variety of purposes other than forensics, pollen analysis has become a standard tool: Government agencies analyze the pollen content of fake Viagra and other prescription drugs to determine where they came from. Museums use pollen to authenticate paintings by master artists. Oil companies study fossil pollen to locate hydrocarbon deposits. Archaeologists study pollen to learn how ancient human communities used plants, and even the seasons at which they occupied a particular site. And paleobotanists study pollen evidence to reconstruct former environments, thousands or even millions of years into the past.

As scientific evidence, pollen has the advantage of being widely distributed, produced in vast quantities (researchers talk about the “pollen rain”), relatively easy for an expert to sort by species and extraordinarily resistant to decay.

The science of interpreting this evidence is called palynology, from the Greek meaning “the study of scattered dust.” Experts in the field preferred that name, a 1940s coinage, to pollenology, or pollen analysis, because this branch of science also encompasses spores, cysts and other microscopic residues of ferns, fungi, mosses, algae and even some animals.

Actual pollen is merely the best-known subject of study, and the most spectacular. Under a microscope, the individual grains of pollen from different species can look like soccer balls, sponges, padded cushions, coffee beans, or burr balls from the sweetgum tree. Their surfaces are covered with intricate geometric patterns—all spikes, warts and reticulations. Ernst Haeckel’s drawings of radiolarians come to mind. So do Buckminster Fuller’s buckyballs.

Pollen has a sturdy, cuticular outer wall, called the exine, and a delicate cellulose inner wall, the intine. Both serve to protect the sperm nucleus on the sometimes harrowing trip by way of a bat’s nose or a honeybee’s hind end, from the male anther to the female stigma. (The spikes and other surface ornaments help the pollen hang on. But other kinds of pollen have wing-like structures for riding on the wind.) The intine soon decays. The exine not only survives this trip, but if buried quickly, can last almost forever, preserved in the fossil record.

These structures “are very resistant to most biological forms of attack,” says Andrew Leslie, a postdoctoral fellow in paleobotany at Yale. “In the right setting, you can get spore grains from ferns that are fairly unaltered back to 470 million years ago and pollen from seed plants back 375 million years.”

Leslie estimates that a medium-sized black pine can produce 10 billion pollen spores, mostly released over the course of a single week each year. The combination of abundance and durability has made pollen an important tool for understanding how plant communities change over long periods of time. The standard technique is to drill into a study site and extract a stratigraphic core, giving the researcher a sort of layer-cake look into the past. Archaeologists also sometimes scrape away the vertical surface of a dig to get a clean profile, then remove soil samples every few inches, working from the bottom to the top to avoid contamination by falling dirt.

Back in the laboratory, each sample goes through repeated hydrochloric acid baths, which destroy everything except the almost immortal exine. The palynologist then puts the material on a microscope slide to determine how many species are present (worldwide almost a half-million species make pollen) and calculate the proportion of different species. That makes it possible to describe how the world looked in different time periods.

A recent study in Science, for instance, used pollen cores to demonstrate that extinction of Australia’s giant marsupials and other megafauna 40,000 years ago triggered the shift away from mixed rainforest habitat. Another study in Science examined the pollen record for southern Greenland and found that a conifer forest grew there during a period of natural warming 400,000 years ago.

What studying pollen gives scientists, in other words, is the means to do what the poet William Blake once imagined:

To see a world in a grain of sand,

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

Add to that the ability to solve the occasional murder and palynology begins to sound like the kind of career a kid could grow up dreaming about.

June 18, 2012

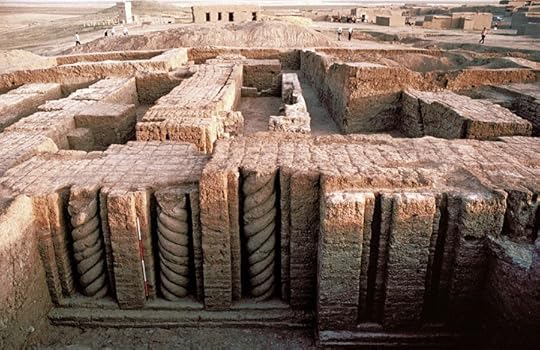

When Civilizations Collapse: Conclusion

The dig at Tell Leilan

The Khabur River rises in Turkey and then flows south through eastern Syria, parallel to its border with Iraq, before joining the Euphrates. Harvey Weiss first arrived there in 1978 as a young archaeologist at Yale. He recalls being impressed by the harvested wheat stacked in “huge mounds” at the train station—“You don’t see that sort of thing growing up in Queens”—and it immediately struck him how productive unirrigated, rain-fed “dry farming” could be.

His focus was on the site now called Tell Leilan. Even before the height of the Akkadian empire almost 5,000 years ago, it grew from a rural village into one of the most important cities in northern Mesopotamia. The city walls from that era still rise above the Khabur Plains, enclosing almost a square kilometer of the ancient metropolis. The excavations Weiss directed revealed construction during the same period of grain storage and administrative facilities for collecting and shipping barley and wheat. Agriculture was being “commodified” and “imperialized” to support a central government or a distant imperial force. It was the ancient equivalent of the French train station.

But around 2200 B.C., both the major Khabur Plains settlements and the Akkadian Empire suddenly collapsed. The next 300 years have left their mark on Tell Leilan in the form of a thick deposit of wind-blown sand, with no architecture and hardly any trace of human habitation. Those centuries also survive in a desolate contemporary poem long thought to be a fictional account of the divine wrath that ended the empire:

For the first time since cities were built and founded,

The great agricultural tracts produced no grain,

The inundated tracts produced no fish,

The irrigated orchards produced neither wine nor syrup,

The gathered clouds did not rain…

In a 1993 article in Science, Weiss proposed, in effect, that the poem was nonfiction. The gods were, of course, no more to blame than were Ottoman bureaucrats in more recent centuries. But the ancient agricultural collapse was real, and the cause was an abrupt climate change. Co-author Marie-Agnes Courty, a soil scientist at the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris, documented the process of sudden drying that produced wind-blown pellets and dust. Other researchers later confirmed an abrupt region-wide dust-spike. Weiss also linked what happened in Mesopotamia to the simultaneous failure of agricultural civilizations from the Aegean to India. This suggested that abrupt climate change had reduced rainfall and agricultural production across the region, reduced imperial revenues, and thereby caused the collapse of the Akkadian Empire. More recently, cores taken by other researchers from ocean and lake floors, cave stalagmites, and glaciers have indicated that this abrupt climate change was probably global.

Why the climate changed abruptly then remains a mystery. The researchers at Tell Leilan found evidence of a distant volcanic eruption, in the form of rare and microscopic volcanic tephra, but regarded that as insufficient to explain a drought that lasted 300 years. Abrupt climate changes of the past were different from modern climate change, says Weiss, in at least two regards: The cause was natural, not the result of human behavior. And where we now have technological means to track and model climate change, society then “had no prior knowledge and no understanding of the alteration in environmental conditions.”

The 1993 Science paper was one of the first to link an abrupt climate change to the collapse of a thriving ancient civilization. But in the 20 years since then, other researchers have followed with studies implicating abrupt droughts lasting decades or centuries in a variety of other collapses, among them the ancient Cambodian Khmer civilization at Angkor, the pre-Inca Tiwanaku around Lake Titicaca, the great urban center of Tenochtitlan in ancient central Mexico,and the Anasazi in the American Southwest. Early this year, yet another article in Science reported that the collapse of the Mayan civilization coincided with prolonged episodes of reduced rainfall. Researchers have been careful not to say that climate change directly caused the collapse of civilizations, merely that drought slashed agricultural productivity and likely aggravated social and political unrest, ultimately leading people to abandon the area.

But many archaeologists have been skeptical of any connection between climate change and the collapse of civilizations.And,at times,the response has displayed all the loopy vehemence of the modern climate change debate, taking denial back 5,000 years. Critics have characterized such research as “environmental determinism” and dismissed the proliferation of evidence as merely a “bandwagon” product of an intellectual zeitgeist that is, as one 2005 a1rticle in a scholarly journal put it, “suddenly sympathetic to the idea of environmentally triggered catastrophes.” That article even seemed to categorize the idea of climate-induced collapse with “Nazi-tainted eugenic theories” about Darwinian determinism. The authors acknowledged that the Akkadian and some other collapses “were of a scale and a rapidity that seemed impossible to explain by purely cultural means.”But they complained that paleoclimate researchers fail to take account of “the inseparable nature of environmental and cultural influences.”In place of farms drying up and people going hungry, the authors preferred to explain it all in terms of cascading collapses in self-organizing systems, “as easily triggered by a pebble as by a boulder.” But not, apparently, by a loaf of bread.

“There’s a book a year,” Weiss said, incredulously, “that claims to point out the errors, lapses, gaps in data and misinterpretations” in the relationship between abrupt climate change and regional collapse. “It’s almost like, ‘Do you believe in evolution?’ They don’t ‘believe in’ the paleoclimate data and they don’t understand that the settlements that remained on the Khabur Plains after the abrupt climate change were few, tiny and short-lived.”

But paleoclimatologists have perhaps been too quick “to couple climatic and human events,” said co-author David Kaniewski. This encouraged traditional archeologists to treat the climate data “as simplistic, just because it failed, in their minds, to adequately consider and make enough room for the social and political context.” Paleoclimatologists and archaeologists could work together more closely “to study coupled natural and social systems.”

The PNAS paper notes that drought periods have become more intense and disruptive in the Middle East just in the past decade and are likely to become more common in the near future. “Interacting with other social, economic and political variables, they act as a ‘threat multiplier’” in a region that has plenty of threats to start with and that has also long exceeded the water needs of its population. One drought that lasted from 2007 to 2010 displaced hundreds of thousands of people in the Tigris and Euphrates basin, suggesting that Syria faces “the same environmental vulnerability as in antiquity.”

Nationwide, that drought drove 1.5 million people from the countryside to the cities, with no jobs or other means of support. Such underlying environmental causes rarely get much attention in reporting on the protests and violent crackdown in Syria. But they are liable to be a recurring challenge even if political and human rights issues get resolved. (Weiss has suspended his research at Tell Leilan because of the continuing crisis. But he has a research permit to drill a pollen core in a swamp alongside the nearby Iraqi border. Asked if he will be able to do the work before the permit expires, he shrugs and says, “I always go back. Let us hope the present tragedy ends quickly.”)

“In spite of technological changes,” Weiss has written elsewhere, “most of the world’s people will continue to be subsistence or small-scale market agriculturalists,” who are just as vulnerable to climate fluctuations as they were in past societies. In the past, people could go elsewhere.

“Collapse is adaptive,” says Weiss. “You don’t have to stay in place and suffer through the famine effects of drought. You can leave. And that’s what the population of the Khabur Plains did. They left for refugia, that is, places where agriculture was still sustainable. In Mesopotamia, they moved to riverine communities.” But climate change is now global, not regional, and with a world population projected to exceed 9 billion people by midcentury, habitat-tracking will inevitably bring future environmental refugees into conflict with neighbors who are also struggling to get by.

One of the most important differences between modern climate change and what he is describing at Tell Leilan, said Weiss, is that we can now anticipate and plan for climate change. Or we can do nothing. The danger is that, when there’s no longer any grain to stack up at the train station, the strategy of collapse-and-abandon may be streamlined to a simpler form: Collapse.

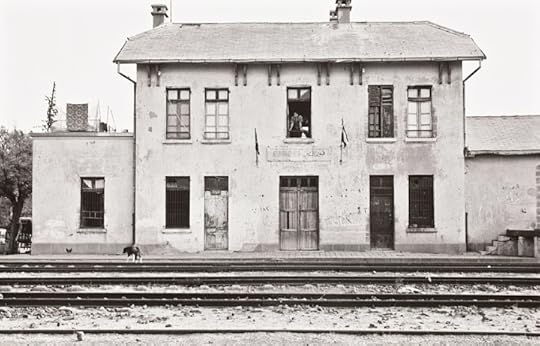

When Civilizations Collapse

For the past 30 years, midway through the drive from his expedition living quarters in Qahtaniyah to his archeological excavation at Tell Leilan in northeastern Syria, Harvey Weiss has contemplated the enigma of a railroad station. French colonial authorities built the modest two-story structure, along with a railroad to the Mediterranean Sea, shortly after World War I, and everything about it belongs in rural France—the hipped roof, the multipaned casement windows, the interior post-and-beam timbers. It is the architecture of empire, writ small.

For the past 30 years, midway through the drive from his expedition living quarters in Qahtaniyah to his archeological excavation at Tell Leilan in northeastern Syria, Harvey Weiss has contemplated the enigma of a railroad station. French colonial authorities built the modest two-story structure, along with a railroad to the Mediterranean Sea, shortly after World War I, and everything about it belongs in rural France—the hipped roof, the multipaned casement windows, the interior post-and-beam timbers. It is the architecture of empire, writ small.

For Weiss, though, the train station has come to tell a larger story about climate change and human adaptation to it (or failure to adapt)over thousands of years. The French built it, he explained recently, to pull out the cereal harvest of the Khabur Plains, the most fertile rain-fed agricultural area in northern Mesopotamia, and it still serves that function. At harvest time, the 100-kilo sacks of wheat are piled high there, awaiting shipment to market.

But why was the Khabur region barren and largely abandoned for hundreds of years before the French arrived? “Why do all the 18th- and 19th-century travel accounts indicate that the region was empty?” asked Weiss. “And what is the meaning of that abandonment for the Ottoman economy and the historical problem of Ottoman decline?” Other scholars have argued for the past 50 or more years that provincial administrators in the declining centuries of the empire were corrupt, inefficient and unable to maintain law and order, allowing the region to be abandoned despite its high productivity and its tax value for the central government. “The argument being,” Weiss added, “that there were no environmental and certainly no climate reasons for the abandonment.”

The alternative answer, in the title of a paper just published by Weiss and his French co-authors in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may seem unsurprising: “Drought is a recurring challenge in the Middle East.” But it has been the subject of bloody academic combat ever since Weiss first proposed 20 years ago that long-term shifts in climate are a key factor in understanding the tumultuous history of the Middle East. Before then, archaeologists working in the region took it for granted that the climate had been essentially stable and benign over the long-term, and that social, political, military and economic forces were the key determinants in the rise and fall of civilizations.

The new study suggests merely that climate change caused the late Ottoman abandonment of the Khabur River Plains, not collapse of the entire Ottoman Empire. But it also makes the case that archaeologists and historians ignore climate change at their peril. “There is an environment in which history occurs,” said Weiss. “There are reasons for regional abandonments that are definable, observable and testable,” even when ancient peoples have left no written record of climate changes.

For the new study, Weiss and co-authors David Kaniewski and Elise Van Campo from the Université de Toulouse, France, used pollen to reconstruct 10,000 years of climate history in the region. Their technique was to take a column of stratified sediment from the side of a dry river channel near Tell Leilan and identify the mix of plant types in different layers. The percentage of pollen in a sample from dry climate plants (like dryland wormwood and tamarisk) or humid climate plants (like flowering sedges and buttercups) provided a measure for estimating rainfall and agricultural productivity at that period. To construct a chronology, the researchers determined radiocarbon ages on plant remains in different layers, using mass spectrometry.

The pollen record showed a pattern of climate fluctuations, with periods of relatively moist climate vegetation alternating with periods of arid climate vegetation. One such dry spell began suddenly around 1400 and lasted until the beginning of the 20th century, the same bleak era when Weiss’s regional archaeological surveys showed villages on the Khabur Plains being emptied. Because this part of Syria is semi-arid to start with and most farmers depend on a single crop of wheat or barley grown in the moist winter months, people then, as now, were highly vulnerable to climate fluctuations. In the absence of irrigation or other technological means of adapting, they practiced what Weiss characterizes as “habitat-tracking,” or moving to areas that could still sustain agriculture.

The evidence suggests, in other words, that incompetent Ottoman bureaucrats were not solely to blame for the demise of agriculture on the Khabur Plains, nor do ingenious French bureaucrats deserve much credit for its 20th-century revival. An intervening force was climate change. And those two words, together with the idea of collapsing civilizations, may explain the intensity of the reaction and the abundance of research Weiss’s work has provoked. (To be continued.)

June 11, 2012

Drawing the Line Between Science and Religion

This is an interesting criticism of The Species Seekers, on the grounds that I fail to draw a sufficiently sharp line between evolutionary knowledge and religious belief. It’s from a curiously named blog–the new ussr illustrated: assorted reflections from the urbane society for sceptical romantics. I’ll let the writer have his say, and respond afterward:

I’m very much enjoying Richard Conniff’s book The Species Seekers: Heroes, fools and the mad pursuit of life on Earth, not only for its well-told anecdotes of an intrepid era but also for its genuine insights into the competitive, gentlemanly and class-riven pursuit of specimens in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in Britain. It includes the hate-hate relationship between the two giants of eighteenth century biology, the great taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus and the more sceptical and polymathic Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon; the snobbish anti-continental attitude to the ideas of Lamarck; the too-good-to-be-true modesty of the Reverend Thomas S Savage, the ‘first identifier’ of the gorilla, and the delicate issue of priority in the matter of Darwin and Wallace’s ideas, obviously the most important ideas, in respect of species, in the history of biology. I’ve already read quite a few versions of this famous matter, having read Peter Raby’s biography of Wallace, and biographical works on Darwin by Rebecca Stott, David Quammen and others. Conniff’s brief treatment does well to capture the intricate play of class, hierarchy and deference involved. After discussing the occasionally offhand treatment of Wallace, and his sometime partner in specimen-collecting, Henry Walter Bates, by the aristocratic geologist Charles Lyell, he goes on to make this nice point:

From a modern perspective, though, Wallace had class issues of his own, like almost all field naturalists. In their book The Bird Collectors, Barbara and Richard Mearns celebrate the unsung contributions to science by native collectors, and they single out the ornithologist Frederick Jackson for the appropriateness of his response when a species was named Jackson’s Weaver [Ploceus jacksoni] in his honour: ‘Little credit is due to me for having brought this new species to light, as the specimen was brought to me by a little Taveita boy, tied by the legs along with several other of the common yellow species’.

Wallace, despite being far more egalitarian than most intellectuals of his time, didn’t always make such acknowledgements.

But I want here to focus on a little quibble I have with Conniff on the not-so-little matter of the science-religion relationship. That’s to say, compatibilism. It’s long-standing issue and I’ve written on it many times before, but it keeps on bobbing up as an eyesore. Here’s Conniff’s take on it, which is essentially the same as that of the USA’s NCSE [National Centre for Science Education] and AAAS [American Association for the Advancement of Science]. That’s to say, religion is compatible with science, because, hey, some people are comfortable with and attached to both enterprises. Here’s how Conniff treats the matter:

Even before publication, the clergyman, naturalist Charles Kingsley saw that evolutionary thinking and religious faith were separate and capable of coexisting: ‘If you be right, I must give up much that I have believed and written,’ Kingsley wrote, in a letter thanking Darwin for an advance copy of the book. ‘In that I care little… Let us know what is… I have gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that he created primal forms capable of self-development into all forms needful… as to believe that he required a fresh act of intervention’ to fill every gap caused by the natural processes ‘he himself had made. I question whether the former be not the loftier thought.’ It might be better, that is, to believe in a God who promulgated laws and let them take their natural course, than to believe in a God obliged, as Buffon had put it, to busy himself about ‘the way a beetle’s wing should fold.’

But evolutionary thinking inevitably struck those of weaker faith as an assault on religion, much as it does today. They read into it the loss of the special relationship with God.

Kingsley’s obviously genuine interest in what is, is admirable, but I hardly think it is a sign of the strength of his religion. Rather, I would consider this interest to be the first, essential step in divesting oneself of religion, which is certainly not about this world. The idea of the ‘separateness’ of science and faith smacks of Gould’s NOMA, a thoroughly debunked notion, but politically convenient. The fact is, as Kingsley himself notes, accepting evolutionary thinking necessitates a thorough rethinking of the creator-god. Kingsley reflects that a non-interventionist god might be a ‘loftier’ conception, but surely a non-interventionist god by definition will not answer prayer, will not heal the sick or go out of his way to protect us from harm. Further, evolutionary thinking really does cause damage to humanity’s ‘special relationship with God’. To become aware of this isn’t a matter of weak faith, it’s more a matter of profound understanding of the real implications of evolution, that we are one of an enormous multiplicity of evolved beings.

Conniff says no more about the issue than this. He doesn’t enter into the compatibility debate. Yet he shows his hand. It’s disappointing. Basically he should’ve put up – presented an argument for how a Christianity so essentially based on human specialness and closeness-to-god, can co-exist, not only with evolution, but with science more generally, when science keeps on eroding human specialness with every passing day of new research – or he should’ve shut up.

Maybe I’m being a bit tough, but I couldn’t let it pass. Otherwise, it’s a great read.

So my response is pretty simple, but I hope not simple-minded. First, I’m grateful for the kind words. But I see no benefit in forcing people to choose between evolution and religion. One is about science, the other about faith, two separate spheres. It’s a bit like forcing people to choose between physics and music, or between detective novels and romance fiction. Insisting that the one makes the other impossible just antagonizes people who might otherwise be open to new ideas.

I also take a pragmatic approach. As I have written here and here, religions are the world’s largest NGOs. Though they are sometimes adversaries–as when the Catholic Church resists contraception, or certain fundamentalist Christians deny climate change (or welcome it as the first step on route to the rapture), it is far better to have them on our side as allies in the fight for the survival of Planet Earth.

Oh, and one other pragmatic point: In the context of a book about species discovery, the kind of larger digression about religion the writer proposes would have been out of place.

May 30, 2012

Personal Heroes: Inky Clark

Having written lately about Yale’s prominent role in eugenics, I’d like to make a paradoxical-seeming statement of gratitude to a character who was, at least superficially, built on the eugenicist’s model of the ideal man.

Russell Inslee “Inky” Clark Jr. is one of my personal heroes. He was a graduate of the Yale Class of 1957 and a member of Skull and Bones, the secret society known for its plutocratic membership, including George H.W. Bush, Averill Harriman, and also the prominent eugenicist Irving Fisher. Clark would go on to spend much of his career as headmaster of a prep school, Horace Mann in New York City. But before that, in 1965, he became director of undergraduate admissions at Yale, and he proceeded to re-make the university on a meritocratic model.

Instead of getting into Yale because you came from the right sort of family, or went to the right schools, or simply because you were entitled, old boy, you could now get in because you somehow seem to have earned it. You could get in just because you were smart enough or because you showed the dim beginnings of a talent.

It didn’t matter, at least not as much, that you were a Jew, or a public school graduate, or in my case an Irish-Italian Catholic from a big and not so bright parochial high school in Newark, NJ. Thanks to Clark and the president of Yale at that time, Kingman Brewster, it soon ceased to matter that you were not a white male.

Here’s how the Yale Alumni Magazine described what Clark achieved, in an article published around the time of his death in 1999 (my bold face added).

But there was nothing inevitable about Yale’s move towards greater meritocracy and diversity, or the institution’s leadership among selective universities on these issues during the 1960s. These outcomes were a result of Kingman Brewster’s personal leadership, and his willingness to endure the opposition that came as a price for his idealism. Clark remembered that in the first year of his deanship, he was hauled before the [Yale] Corporation to report directly on his changes in admissions policy. One of the Corporation members who had “hemmed and hawed” throughout Clark’s presentation finally said, “Let me get down to basics. You’re admitting an entirely different class than we’re used to. You’re admitting them for a different purpose than training leaders.” Clark responded that in a changing America, leaders might come from nontraditional sources, including public high school graduates, Jews, minorities, and even women. His interlocutor shot back, “You’re talking about Jews and public school graduates as leaders. Look around you at this table”—this was at a time when the Yale Corporation included some of America’s most powerful and influential men. “These are America’s leaders. There are no Jews here. There are no public school graduates here.”

Those days are of course now long gone, and our universities and the country are infinitely better places for it.

My own life has also been better than I had any reason to expect, and every so often I think about Inky Clark and thank him for it. Once at a dinner party, I mentioned to a friend that Inky Clark was the reason I got into Yale. And the friend, whose close relative A. Whitney Griswold had been president of Yale in the 1950s, immediately replied, with a smile, “And he’s the reason I didn’t.”

I think it worked out o.k. for both of us.

What Inky Clark wrought also worked out well for a great many other people, of all types, as I am reminded by this joyous, poignant note written by a new Yale graduate who died this past weekend.

May 22, 2012

The Earth Moved

This is a story I wrote for the June issue of Smithsonian Magazine. The editors there asked me to write a different lead, to make it seem more timely. You can read that version here. But I think the historical account stands on its own. Feel free to disagree in the comments:

Alfred Wegener

On November 1, 1930, his fiftieth birthday, a German meteorologist named Alfred Wegener set out with a colleague on a desperate 250-mile return trip from the middle of the Greenland ice pack back to the coast. The weather was appalling, often below minus-60 degrees Fahrenheit. Food was scarce. They had two sleds with 17 dogs fanned out ahead of them, and the plan was to butcher the ones that died first for meat to keep the others going.

Less than halfway to the coast, down to seven dogs, they harnessed up a single sled and pushed on, with Wegener on skis working to keep up. He was an old hand at arctic exploration. This was his fourth expedition to study how winter weather there affected the climate in Europe. Now he longed to be back home, where his wife Else and their three daughters awaited him. He dreamed of “vacation trips with no mountain climbing or other semi-polar adventures” and of the day when “the obligation to be a hero ends, too.” But he was also deeply committed to his work. In a notebook, he kept a quotation reminding him that no one ever accomplished anything worthwhile “except under one condition: I will accomplish it or die.”

That work included a geological theory, first published a century ago this year, that sent the world woozily sliding sideways and also outraged fellow scientists. We like to imagine that science advances unencumbered by messy human emotions. But Wegener’s brash intuition threatened to demolish the entire history of the Earth as it had been built up step by step by generations of careful thinkers. The response from fellow scientists was a firestorm of moral outrage, followed by half a century of stony silence.

Wegener’s revolutionary idea was that the continents had started out massed together in a single supercontinent and then gradually drifted apart. He was of course right. Continental drift, and the more recent science of plate tectonics, are now the bedrock of modern geology, helping to answer life-or-death questions like where earthquakes may hit next, and how to keep San Francisco standing. But in Wegener’s day, drift was heresy. Geological thinking stood firmly on solid earth, continents and oceans were permanent features, and the present-day landscape was a perfect window into the past.

The idea that smashed this orthodoxy got its start at Christmas 1910, as Wegener (the W is pronounced like a V) was browsing through “the magnificent maps” in a friend’s new atlas. Others before him had noticed that the Atlantic Coast of Brazil looked as if it might once have been tucked up against West Africa like a couple sleeping in the spoon position. But no one had made much of this matchup, and Wegener was hardly the logical choice to show what they had been missing. At that point, he was just a junior university lecturer, not merely untenured but unsalaried, apart from meager student fees. Moreover, his specialties were meteorology and astronomy, not geology.

But Wegener was not timid about disciplinary boundaries, or much else: He was an Arctic explorer and had also set a world record for endurance flight as a balloonist. When his mentor and future father-in-law, one of the eminent scientists of the day, advised him to be cautious in his theorizing, Wegener replied, “Why should we hesitate to toss the old views overboard?” It would be like heaving sandbags out of a gondola.

Wegener proceeded to cut out maps of the continents, stretching them to show how they might have looked before the landscape crumpled up into mountain ridges. Then he fit them together on a globe, like jigsaw puzzle pieces, to form the supercontinent he called Pangaea. Next, he pulled together biological and paleontological records showing that, in regions on opposite sides of the ocean, the plants and animals were often strikingly similar: It wasn’t just that the marsupials in Australia and South America looked alike; so did the flatworms that parasitized them. Finally, he pointed out how layered geological formations, or stratigraphy, often dropped off on one side of the ocean only to pick up again on the other. It was as if someone had torn a newspaper sheet in two, and yet you could still read a sentence across the tear.

Wegener presented the idea he called “continental displacement” in a lecture to the Frankfurt Geological Association early in 1912. The meeting ended with “no discussion due to the advanced hour,” much as when Darwinian evolution made its debut. He published his idea for the first time in an article later that year. But before the scientific community could muster much of a response, World War I broke out. Wegener served in the German army on the Western Front, where he was wounded twice, in the neck and arm. Hospital time gave him a chance to extend his idea into a book, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, published in German in 1915. Then, with the appearance of an English translation in 1922, the bloody intellectual assault began.

Lingering anti-German sentiment no doubt aggravated the attack. But German geologists also scorned the “delirious ravings” and other symptoms of “moving crust disease and wandering pole plague.” Wegener’s idea, said one of his countryman, was a fantasy “that would pop like a soap bubble.” The British likewise ridiculed Wegener for distorting his jigsaw-puzzle continents to make them fit, and, more damningly, for failing to provide a credible mechanism powerful enough to move continents. At a Royal Geographical Society meeting, an audience member thanked the speaker for having blown Wegener’s theory to bits–then also archly thanked the absent “Professor Wegener for offering himself for the explosion.”

But it was the Americans who came down hardest against continental drift. Edward W. Berry, a paleontologist at Johns Hopkins University called it “Germanic Pseudo-Science” and accused Wegener of cherry-picking “corroborative evidence, ignoring most of the facts that are opposed to the idea, and ending in a state of auto-intoxication.” Others poked holes in Wegener’s stratigraphic connections and joked that an animal had turned up with its fossilized head on one continent and its tail on another. They argued that similar species had arrived on opposite sides of oceans by rafting on logs, or by traveling across land bridges that later collapsed.

At Yale, paleogeographer Charles Schuchert focused on Wegener’s lack of standing in the geological community: “Facts are facts, and it is from facts that we make our generalizations,” he said, but it was “wrong for a stranger to the facts he handles to generalize from them.” Schuchert showed up at one meeting with his own cut-out continents and clumsily demonstrated on a globe how badly they failed to match up, geology’s equivalent of O.J. Simpson’s glove.

The most poignant attack came from a father-son duo. Thomas C. Chamberlin had launched his career as a young geologist decades earlier with a bold assault on the eminent British physicist Lord Kelvin. He had gone on to articulate a distinctly democratic and American way of doing science, according to Naomi Oreskes, author of The Rejection of Continental Drift–Theory and Method in American Science. Old World scientists tended to become too attached to grandiose theories, said Chamberlin. The true scientist’s role was to lay out all competing theories on equal terms, without bias. Like a parent with his children, he was “morally forbidden to fasten his affection unduly upon any one of them.”

But by the 1920s, Chamberlin was being celebrated by colleagues as “the Dean of American Scientists,” and a brother to Newton and Galileo among “great original thinkers.” He had become not merely affectionate but besotted with his own “planetismal” theory of the origin of the Earth, which treated the oceans and continents as permanent features. This “great love affair” with his own work was characterized, according to historian Robert Dott “by elaborate, rhetorical pirouetting with old and new evidence.” Chamberlin’s democratic ideals—or perhaps some more personal motivation–required grinding Wegener’s grandiose theorizing underfoot.

Rollin T. Chamberlin, who was, like his father a University of Chicago geologist, stepped in to do the great man’s dirty work: The drift theory was “of the foot-loose type … takes considerable liberties with our globe,” ignores “awkward, ugly facts,” and “plays a game in which there are few restrictive rules and no sharply drawn code of conduct. So a lot of things go easily.” Young Chamberlin also quoted an unnamed geologist’s remark that inadvertently revealed the heart of the problem: “If we are to believe Wegener’s hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again.”

Instead, geologists largely chose to forget Alfred Wegener, except to launch another flurry of attacks on his “fairy tale” theory in mid-World War II. For decades after, older geologists quietly advised newcomers that any hint of the drift heresy would end their careers.

Wegener himself was exasperated but otherwise undaunted by his enemies. He was careful to address valid criticisms, “but he never backtracked and he never retracted anything,” says Mott Greene, a University of Puget Sound historian whose biography, Alfred Wegener’s Life and Scientific Work comes out later this year. “That was always his response: Just assert it again, even more strongly.” By the time Wegener published the final version of his theory in 1929, he felt certain that continental drift would soon sweep aside other theories and pull together all the accumulating evidence into a single unifying vision of the Earth’s history. He didn’t pretend to know for certain what mechanism would prove powerful enough to explain the movement of continents. But he reminded critics that it was commonplace in science to describe a phenomenon (for instance, the laws of falling bodies and of planetary orbits) and only later figure out what made it happen (Newton’s formula of universal gravitation). He added, “The Newton of drift theory has not yet appeared.”

The turnabout on Wegener’s theory came relatively quickly, in the mid-1960s, as older geologists died off, unenlightened, and a new generation accumulated irrefutable proof of sea-floor spreading, and of vast tectonic plates grinding across one another deep within the Earth. Else Wegener lived to see her husband’s triumph. Wegener himself was not so fortunate.

That 1930 expedition had sent him out on an impossible mission. A subordinate had failed to supply enough food for two members of his weather study team spending that winter in the middle of Greenland’s ice pack. Wegener and a colleague made the delivery that saved their lives. He died on the terrible trip back down to the Coast. His colleague also vanished, lost somewhere in the endless snow. Searchers later found Wegener’s body and reported that “his eyes were open, and the expression on his face was calm and peaceful, almost smiling.” It was as if he had already foreseen his vindication.

May 16, 2012

When Alabama Stood Up for Freedom

Alabama is on the brink of passing a highly punitive law against immigrants, and it reminded me or an item from my eugenics story that ended up on the cutting room floor. In the 1930s, when eugenicists at Yale and other leading intellectual institutions were still defending forced sterilization, Alabama stood up for freedom and the fundamental concepts of American life.

Here’s what I wrote:

Even as late as 1940, when the Germans had sterilized 400,000 people, Yale professor Ellsworth Huntington could applaud “the way sterilization is being gradually accepted as a necessary measure for preserving the health of the community.” This was five years after the governor of Alabama, a state not ordinarily known for its progressive thinking, rejected a proposed sterilization law*, declaring that “the country people of Alabama do not want this law; they do not want Alabama, as they term it, Hitlerized.”

Maybe it’s time now for Alabama to remember its own best impulses. Here’s an excerpt from an editorial about the proposed immigration law in today’s New York Times:

The Supreme Court recently heard oral arguments on the constitutionality of Arizona’s immigration law, whose noxious spirit and letter Alabama has copied. A ruling in that case is expected in June, and could unleash more Arizona-style damage in other states. Meanwhile, the two Republican architects of Alabama’s immigration law, Micky Hammon in the House and Scott Beason in the Senate, are pressing on. And The Associated Press reported this month that Alabama farmers are planting less and shifting to mechanized crops as the reality of an immigrant labor shortage — the high price of xenophobia — sinks in.

* Kline, W., Building a Better Race, p. 80

May 8, 2012

Adolph Gave Good Blurbs (Postscript)

Whitney (with “Fitter Family” promoters)

The most appalling moment in the literary history of Yale occurred in Madison Grant’s Wall Street law office during the thick of the Depression. The secretary of the American Eugenics Society then was a New Haven veterinarian named Leon F. Whitney, author of The Complete Book of Dog Care and other pet titles; he later worked as a pathology instructor at Yale Medical School, until his retirement in 1964, and his collection of champion dogs ended up at the Peabody Museum, where they are still among the most actively studied specimens.

In 1934, Whitney published a book called The Case for Sterilization, which was not about neutering the family dog. To the question how many Americans “ought to be sterilized,” he added up “all the various types of less useful social elements,” noting that they tended to occur disproportionately in blacks and immigrants. Then he concluded that “we should probably be disposing of the lowest fourth of our population”—or roughly 30 million people. He quickly added that he was not “suggesting that all these be sterilized wholesale, but merely that we make voluntary sterilization available to them.”

One of Hitler’s staff wrote to New Haven requesting a copy of the book, and Hitler himself later followed up with a personal letter of thanks. Soon after, Whitney went down to New York to meet with his fellow eugenicist Madison Grant, and proudly showed him the letter. In the 1994 book The Nazi Connection, historian Stefan Kühl writes: “Grant only smiled, reached for a folder on his desk,” and gave Whitney his own letter, in which Hitler thanked Grant for writing The Passing of the Great Race and called it his “Bible.”

May 3, 2012

From Polemics to Murder (God & White Men–Conclusion)

By then, Fisher himself had stopped campaigning publicly for eugenics, and no longer tried to work the notion of the nation’s racial stock into economics discussions. His old ally Madison Grant died in 1937, and Fisher seemed to recognize the alarming effects of their earlier efforts together. In 1938, he joined three other economists in attacking the radio personality Father Charles Coughlin, a notorious anti-Semite, for adding “fuel to the already blazing flames of intolerance and bigotry.” A year later, he was one of the signatories to a public letter issued by Christian and Jewish institutions, cautioning Americans “against propaganda, oral or written” that sought to turn classes, races, or religious groups against one another. The letter warned, poignantly: “The fires of prejudice burn quickly and disastrously. What may begin as polemics against a class or group may end with persecution, murder, pillage, and dispossession of that group.”

Fisher survived World War II, dying in 1947 at the age of 80. His major causes by then were warding off deflation and requiring banks to hold larger reserves against their deposits, proposals that remain relevant in the post–Lehman Brothers era. We do not know how Fisher, Yerkes, Huntington, or other eugenicists responded to the discovery of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and other centers of racial hygiene. No doubt they were horrified.

Karl Brandt

Grant’s Passing of the Great Race would turn up once more after the war, at Nuremberg. Hitler’s personal physician Karl Brandt had been charged with brutal medical experiments and murder in the concentration camps. His lawyers introduced Grant’s book into evidence in his defense, arguing that the Nazis had merely done what prominent American scholars had advocated. Brandt was found guilty and sentenced to death.

We know better now, of course. And yet eugenic ideas still linger just beneath the skin, in what seem to be more innocent forms. We tend to think, for instance, that if we went to Yale, or better yet, went to Yale and married another Yalie, our children will be smart enough to go to Yale, too. The concept of regression toward the mean—invented, ironically, by Francis Galton, the original eugenicist—says, basically: don’t count on it. But outsiders still sometimes share our eugenic delusions. Would-be parents routinely place ads in college newspapers and online offering to pay top dollar to gamete donors who are slender, attractive, of the desired ethnic group, with killer SAT scores—and an Ivy League education.

Irving Fisher and the other Yale eugenicists would no doubt rejoice that the university’s germ plasm is still so highly valued—at up to ten times the price for other colleges. But if they looked more carefully at the evidence, they would discover that these highly desirable donors are now often the grandsons and granddaughters of the very immigrants they once worked so hard to eliminate.

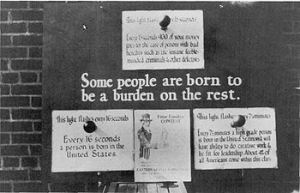

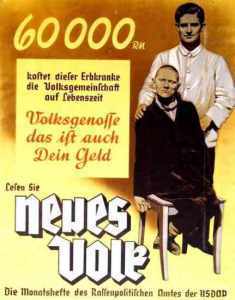

Born to be a burden (Eugenics in the US)

Born to be a burden (eugenics Germany)

May 2, 2012

Into the Lion’s Maw (God & White Men–part 4)

Entirely apart from his reputation as an economist, Irving Fisher enjoyed an idyllic American existence. He lived with his wife Margaret and their three children in a big house on the crest of Prospect Street, with a music room, a library, and “a 40-foot living room with a large, sunny bay window,” as their son Irving recalled in his memoir, My Father Irving Fisher. A health enthusiast at home as well as in public, Fisher disdained cane sugar, tea, coffee, alcohol, tobacco, and bleached white flour. He often jogged in shorts around the neighborhood and liked to ride a bicycle to his classes on the Yale campus. One of his books was titled How to Live.

His various crusades required a platoon of busy assistants. So Fisher built out from the basement of the family home onto the sloping ground in back, eventually creating ten work rooms and, young Irving recalled, a “hidden beehive of activity below decks.” The office equipment included one of Fisher’s own inventions, an index card filing system that made the first line of each card visible at a glance. With his wife’s money, he turned it into a thriving business. When the company was bought out—it would become part of the Sperry Rand corporation—Fisher capitalized on his new wealth by buying stock on margin. By the late 1920s, he and Margaret had a fortune of $10 million.

Fisher was the son of a Congregational minister, and his driving impulse was to proselytize. Thus eugenics seemed a natural outgrowth not just of his work as an economist, but of his family heritage. It needed “to be a popular movement with a certain amount of religious flavor in it,” he thought. His role as a leading apostle also seemed like a way for him to make a real mark on the world—as if his economics alone were not enough: “I do want before I die,” he wrote to his wife, “to leave behind me something more than a book on Index Numbers.”

But his eugenic enthusiasms drew him away from the arc of his true genius. His book The Theory of Interest was “an almost complete theory of the capitalist process as a whole,” according to Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter. But Fisher never found time to pull his ideas together into one grand synthesis, nor did he develop a school of disciples to carry on his work. His books are thus “pillars and arches of a temple that was never built,” Schumpeter wrote. “They belong to an imposing structure that the architect never presented as a tectonic unit.” “Unfortunately,” Yale economist Ray B. Westerfield agreed, “his eagerness to promote his cause sometimes had a bad influence on his scientific attitude. It distorted his judgment.” This was never more nakedly obvious than in October 1929, when Fisher’s enthusiasm for stocks as a long-term investment led him to pronounce that the market had arrived at “a permanently high plateau.” The great Wall Street crash hit shortly after, and it turned America’s greatest economist into a national laughingstock, incidentally leaving the family fortune in ruins.

But the far grosser distortion of judgment, and of his better self, was in Fisher’s campaigning as a eugenicist. His interest in health had arisen largely from his own encounter in 1898 with tuberculosis, the disease that killed his father. It took Fisher three years of fresh air, proper diet, and close medical attention in sanatoriums around the country to regain his health. Having managed to get his own head out of the lion’s mouth, he said in 1903, he wanted to prevent “other people from getting their heads into the same predicament.” His initial approach was to lobby the government to reduce urban pollution, protect the health of mothers and children, and establish school health programs, “so that American vitality may reach its maximum development.” But his almost religious conversion to eugenics, not long after, turned all that upside down. Two decades after his own recovery, Fisher was denouncing “hygiene to help the less fit” as “misapplied hygiene” and “distinctly dysgenic. … Schools for tubercular children give them better air and care than normal school children receive.” He seemed to have forgotten that he was once among those who, by his own harsh standard, deserved to have their heads held fast in the lion’s mouth.