Richard Conniff's Blog, page 98

January 10, 2012

How a Soda Tax Could Save 26,000 Lives a Year

The American addiction to soda has vast consequences for our waistlines and our lives. (The obesity crisis also matters to the health of the planet). Now a study by researchers at Columbia University and the University of California San Franciso say a modest soda tax could save 26,000 lives a year. Here's the press release:

Newswise — Every year, Americans drink 13.8 billion gallons of soda, fruit punch, sweet tea, sports drinks, and other sweetened beverages—a mass consumption of sugar that is fueling soaring obesity and diabetes rates in the United States.

Now a group of scientists at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (SFGH) and Columbia University have analyzed the effect of a nationwide tax on these sugary drinks.

They estimate slapping a penny-per-ounce tax on sweetened beverages would prevent nearly 100,000 cases of heart disease, 8,000 strokes, and 26,000 deaths every year.

"You would also prevent 240,000 cases of diabetes per year," said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, an associate professor of medicine and of epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF and acting director of the Center for Vulnerable Populations at SFGH.

In addition to $13 billion in direct tax revenue, Bibbins-Domingo and her colleagues estimated that such a tax would save the public $17 billion per year in healthcare-related expenses due to the decline of obesity-related diseases.

"Our hope is that these types of numbers are useful for policy makers to weigh decisions," she said.

The High Cost of High Calorie Drinks

Consumption of beverages high in calories but poor in nutritional value is the number one source of added sugar and excess calories in the American diet. Sugar- sweetened drinks are linked to type 2 diabetes and weight gain.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention listed reducing the intake of these beverages as one of its chief obesity prevention strategies in 2009, and several states and cities, including California and New York City, are already considering such taxes.

The analysis by Bibbins-Domingo and her colleagues is among the first study to generate concrete estimates of the health benefits and cost savings of such a tax. They modeled these benefits by taking into account how many sodas and sugary beverages Americans drink every year and estimating how much less they would consume if a penny-per-ounce tax were imposed on these drinks.

Economists have estimated that such a tax would reduce consumption by 10 to 15 percent over a decade.

They then modeled how this reduction would play out in terms of reducing the burdens of diabetes, heart disease and their associated healthcare costs.

The article, "A Penny-Per-Ounce Tax On Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Would Cut Health And Cost Burdens Of Diabetes," by Y. Claire Wang, Pamela Coxson, Yu-Ming Shen, Lee Goldman and Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo appears in the January issue of Health Affairs.

This work was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate.

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

###

Related Information:

U.S. Consumption of Sweet Beverages

13,800,000,000 gallons—total amount consumed by Americans in 2009

45 gallons—average U.S. consumption per person per year

17 teaspoons—the amount of sugar in a typical 22-oz sweet drink

70,000 calories—the average amount every American consumes per year in sweetened beverages

Source: http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.201... 3

Diabetes in the United States

25,800,000—number of Americans who have diabetes

8.3—percentage of the U.S. population affected

$174,000,000,000—annual cost of diabetes in the United States.

7th—leading cause of death in the United States

Source: CDC

Related Links:

UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations at SFGH

http://cvp.ucsf.edu/4

CA Diabetes Program

http://www.caldiabetes.org5

Related Stories:

Sugar Is a Poison, Says UCSF Obesity Expert

http://www.ucsf.edu/news/2009/06/8187...6

Sugary Drinks Are a Big Contributor to New Diabetes Cases, Researchers Say

http://www.ucsf.edu/news/2010/03/5982...

The Species Seekers Quiz: What Lies Beneath the Lid? Love or Loss

[image error]

British naturalist William J. Burchell found something astounding when he took the lid off his collection of vultures. What was it?

1. A new type of Silphidae, or carrion beetle.

2. A skull and bones.

3. An egg in a vulture's stomach.

4. A love letter from the woman who had spurned him.

And the answer is:

A skull and bones. (Sorry, all you romantics, there's a love story about Burchell in The Species Seekers, but not today.)

During his travels in southern Africa from 1811 to 1815, Burchell collected 265 bird species, many of them new to science. But like many other collectors, he came unstuck over the challenge of dealing with his treasures once he got home. In 1819, four years after his return, he confessed to a friend:

"The collection of birds which I made during my travels in Africa has always remained packed up in the chests, nor have I yet been able to get any of them stuffed. The chief reason for which is that they would take up much more room than I have at present in my power to allow them. They have indeed never yet been all seen by any person since my arrival in England."

He was immobilized by the fear of decay:

"I am obliged, in order to secure them from moths and other insects, to keep them so pasted up that I have not myself any access to them, but intend to keep them in this state till I begin to work at the ornithological part of my collection."

Then in 1834, another African traveller, Eduard Rüppell, visited the British Museum and persuaded one of the young keepers there, John E. Gray, to take him to see Burchell's collection. Burchell was deeply reluctant, and ultimately unable, to open his carefully sealed boxes.

So Gray and Rüppell came back a few days later, "provided with a hammer and chisel to prevent a recurrence of the same difficulty. Mr. Burchell laughed at our persistence and agreed to our opening the box containing the Vultures which was most carefully packed," Gray wrote.

But when the lid came off, the box "contained nothing but the naked skull, arm and leg bones, all the rest had been eaten up, and this was unfortunately the state of all the boxes of African birds which we examined much to our grief and disgust." Some species that Burchell had collected would only be "discovered" when Rüppell collected and described them on his own decades later.

But Gray's assessment of the dire condition of Burchell's specimens was overstated. In fact, Burchell seems to have done the fieldwork of preservation with care . The bulk of his collection survives today at the Oxford University Museum, where his southern Africa skins were finally catalogued and named in 1953 , 138 years after the adventurer's return home.

January 8, 2012

Fleas are not Lobsters

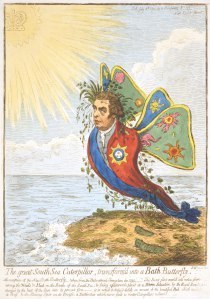

Banks as the Great South Sea Caterpillar

Early naturalists often displayed deep confusion about how different species might be connected to one another. Since the standard belief was that each species was a unique creation by God, some even asserted that there was no connection, merely correlation. We weren't biologically related to monkeys, for instance–it was just a sort of coincidental resemblance, perhaps from God getting lazy and plagiarizing his own work.

When naturalists tried to investigate the possible connections across the plant and animal kingdoms, they sometimes came in for ridicule. I thought about that a little while I go when I came across a satiric roasting of Sir Joseph Banks, the world-traveling naturalist and eminent "natural philosopher" of late eighteenth-century London.

According to the British comic writer Peter Pindar, Banks once supposedly cooked up an experiment to boil fleas, 1500 of them, and see if they would turn red, but was disappointed in his expectations.

"There goes, then, my hypothesis to hell," the naturalist cried, "Fleas are not lobsters, d___n their souls."

January 7, 2012

Wall of the Dead: Conservation Volunteer Drowns in New Zealand

I am very sorry to start the New Year with an early addition to the Wall of the Dead: A Memorial to Fallen Naturalists:

Swept away by rogue wave? Muncus-Nagy

A Romanian conservationist who is believed to have drowned off Raoul Island was fulfilling a life dream to come to New Zealand.

The search for Mihai Muncus-Nagy was called off last night after sea and air searches had failed to find the 33-year-old, who went missing on Monday from Fishing Rock while carrying out routine monitoring on the island in the remote Kermadec group.

The Romanian was in New Zealand for six months, and was one of four volunteers helping three Department of Conservation staff monitor seismic and volcanic activity and conduct conservation work to protect the more than 100 plants native to the Kermadecs.

Department of Conservation chief executive Al Morrison told Radio New Zealand said Mr Muncus-Nagy applied online to volunteer in New Zealand and "ticked all the boxes".

"I understand it was his life dream even as a boy to come and work in New Zealand.

"I can tell you he was an extremely experienced conservation worker and he had a lot of skill. He led teams in Romania into quite rugged areas to do conservation work. He had a Masters degree, I understand he was a botanist."

Mr Morrison said the department had been in contact with the Romanian embassy in Australia and with Mr Muncus-Nagy's wife.

"Obviously she is incredibly distraught and coming to terms with the fact she is unlikely to see her husband again, or even recover her body. It is a terrible tragedy for her being so far away."

The department had offered to bring his wife over to New Zealand and take her to Raoul Island, he said.

Mr Morrison said counselling would be offered to Mr Muncus-Nagy's "tight-knit" colleagues on Raoul Island.

"They're obviously very upset. They're exhausted, they've had a real emotional rollercoaster. They've been searching for him and coming to terms with the fact that they are probably never going to find his body."

Mr Morrison said there would be a Department of Labour investigation into the accident but believed DOC follows best practice regarding volunteers working in remote areas like Raoul Island.

It is believed Mr Muncus-Nagy may be have been washed off the rock by a wave.

"It does look like this was a freak accident," Mr Morrison said.

Burning Down the Library of Life

Should life only matter if it has selfish value to us? A green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, phtographed by Richard Pyle by

I've often tried to explain why species matter, usually by emphasizing the ways they affect human health, though I am acutely aware that this is a narrow, selfish view of the life around us. Deep sea diver Richard Pyle also does some of that in the series of columns he has been writing lately for The New York Times. But in his latest column, he also gets at the precious value of the larger fabric of life on earth, with or without humans.

Pyle, who works at Bishop Museum in Honolulu, is exploring and documenting marine biodiversity as a science adviser for the One World One Ocean initiative. His New York TImes series describes an expedition to Cocos Island, off the Costa Rican coast:

My overarching quest is to document biodiversity — both on this project and in general. The most extraordinary aspect of biodiversity to me is the way in which every living thing on earth, everything that has ever lived on earth, is directly connected through time by an utterly unbroken sequence of reproductive events. I can trace my ancestry back through my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on, generation after generation after generation after generation, back through time.

When we imagine our own family history, we tend to think in terms of a few centuries; but in fact, the pattern goes back much further. Not just a few thousand years, or even a few million years, but several billion years. On that scale of time, every organism that has ever lived is part of a shared family tree.

The fundamental thing that separates life from nonliving chemistry is information. Specifically, it is the way in which information is propagated through time. Much of this information is encoded in the genome, but the information content goes far beyond DNA.

It includes the vastly complex ways in which organisms interact with each other — as predator and prey (whitetip reef sharks and the fishes they hunt), as symbionts (hammerhead sharks at cleaning stations), as organisms living in the shelter of other organisms (a juvenile silverstripe chromis among the branches of a black coral tree) and indeed, as entire ecosystems of interdependent communities of organisms.

Each species is like a book, the product of literally billions of years of editing and re-editing through the process of evolution, and each species has its own unique story to tell. These stories are all nonfiction, and more important, stories of survival, of navigating billions of years of persistence. These stories include the cures to many (if not all) human diseases. They include instructions for converting sunlight into stored chemical energy with near-perfect efficiency. But the most important stories are the ones we have not yet imagined.

We are like kindergartners running through the aisles of the Library of Congress, almost completely unaware of the value of the information around us. We are surrounded by the genomic equivalents of the works of Homer and Shakespeare, or detailed plans to build a nuclear reactor, yet our ability to read and understand this information is still at the stage of "See Spot run."

Biodiversity is earth's greatest library, and we have not matured enough as a species, as a civilization, to realize it yet. Someday soon we will understand how to read the secrets contained within the Biodiversity Library. Unfortunately, we are on the brink of this planet's sixth great extinction event, and each time a species goes extinct, it is like burning the last copy of a book. Once it is gone, the information it contained is lost forever. Earth's greatest library is burning.

The taxonomists of the world, of which I am one, are the librarians. Our job is to build the card catalogs, to document not only the existence and general nature of each book, but also where they can be found.

For the past two and a half centuries, we have managed to document less than 10 percent of the estimated 20 million to 30 million species on earth. The reason it is important to use new technologies like rebreathers and submersibles is not because they are cool, but because we need their help in our race to document biodiversity before it's gone.

The wonderful efforts by the Costa Rican government to protect Cocos Island and its inhabitants need to be expanded to many other parts of the ocean, many other parts of the planet. Efforts like the One World One Ocean campaign help people understand the importance of biodiversity and the importance of protecting it. As my friend Sylvia Earle has said, what we do in the next 10 years will define what happens in the next 10,000. There is no time to waste.

January 4, 2012

The Dark Side of those Shrimp Buffets

On a visit to the coast of Ecuador 20 years ago, I saw the way shrimp farm ponds had wiped out the dense, productive mangrove swamps. Since these swamps had been the main natural breeding ground for shrimp, it amounted to a policy of killing the shrimp to grow shrimp, mainly for those all-you-can-eat buffets so popular in the United States. Now New Zealand's Kennedy Warne has written a book about the problem worldwide, called Let Them Eat Shrimp.

On a visit to the coast of Ecuador 20 years ago, I saw the way shrimp farm ponds had wiped out the dense, productive mangrove swamps. Since these swamps had been the main natural breeding ground for shrimp, it amounted to a policy of killing the shrimp to grow shrimp, mainly for those all-you-can-eat buffets so popular in the United States. Now New Zealand's Kennedy Warne has written a book about the problem worldwide, called Let Them Eat Shrimp.

Here's an excerpt from a recent interview in Grist:

Public awareness and consumer pressure are two key ways to secure a future for mangroves and the people who rely on them. Mangroves don't have the charisma of forests like the Amazon. Rock stars and celebrities don't line up to lend their names to "save the mangrove" initiatives.

I think consumers need to look long and hard at their consumption of farmed shrimp. (And two-thirds of the shrimp consumed in the U.S. is imported farmed product.) Consumers should be asking their suppliers where the shrimp they're selling comes from, and trying to determine not just if it is sustainably farmed, but also what are the social impacts of that farming.

When I was in the U.S. on a book tour recently, I was told that social justice was not a motivating factor for American consumers. That unless I could identify some kind of health problem with eating farmed shrimp, changing consumer behavior was unlikely to happen. But I think change is happening. More and more people are making connections between the food on their plates and the people and pathways involved in producing it. We have the opportunity to make informed, enlightened, ethical choices. For the good of the planet and some of its least visible citizens, we should exercise those choices.

Read the full interview here.

December 31, 2011

"Thoroughly Entertaining Adventure Stories"

The Species Seekers by Richard Conniff (Norton). Ecotourists today expect to be whisked off to remote locations to enjoy intimate views of wildlife from purpose-built hides. But explorers and naturalists formerly risked their lives and their sanity in pursuit of exotic species. Their prize was the thrill of novelty: to be the first to name what are still referred to as "species new to science." In the eighteenth and ninteenth centuries, explorers thought nothing of battling with malaria, starvation or shipwreck to bring home the prize of a beautiful but unnamed bird or butterfly. Richard Conniff provides a thoroughly entertaining series of adventure stories revealing these taxonomic heroes, amply peppered with tales of rogues and nadmen. Many of these scientists are as exotic as the species they sought to discover.

December 30, 2011

Camera Trap Art from Afghanistan

Camera traps around the world have been accumulating some spectacular and revealing images of wildlife, without disturbing the animals. Here's the latest. A Wilderness Conservation Society camera trap caught this image of a snow leopard mother and cub on a craggy peak in Afghanistan's Sarkund Valley.

Camera traps around the world have been accumulating some spectacular and revealing images of wildlife, without disturbing the animals. Here's the latest. A Wilderness Conservation Society camera trap caught this image of a snow leopard mother and cub on a craggy peak in Afghanistan's Sarkund Valley.

December 28, 2011

Using Chicken Coops to Replace Bushmeat

The New York Times has a report on the nuances of the trade in monkeys and other bushmeat, a threat to wildlife everywhere. It raises the interesting possibility that making chickens widely available would provide people with an alternative way to feed their families.

I have always been a little suspicious of Heifer International, because the idea of providing environmentally demanding cattle to poor families just seemed like a way to increase the destruction of habitat. But chickens get around that objection.

Here's the relevant part of the Times article:

Fortunately, rare species did not seem to be priced any higher than common ones. For example, primates fetched about the same price as brush-tailed porcupines, which are more common.

This is good news for conservation, since it suggests that people could be steered away from the rarer animals and encouraged to focus on common species.

The researchers suspect that alternative protein sources, like poultry or livestock, are missing from villagers' menus simply because they are not available. "There's no tradition of keeping livestock," Dr. Foerster said. "Perhaps one approach could be making certain species of livestock more available and widespread."

Other studies found that Central Africans usually rank chicken similarly to their favorite bush meat varieties, so the potential may exist for alleviating pressure on wild species by introducing poultry farming.

How We Forget the World We Have Lost

In an article earlier this year about the hidden value of species, I wrote about how much, and in how many ways, the dramatic decline in its vultures had cost India.

When we cause a species to go into decline, we almost never know — and hardly even stop to think about — what we might be losing in the process. In truth, it may be hard to think about, because the cascading effects of our actions are sometimes freakishly distant from the original cause. So in India in the early 1990s, farmers began using the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac for the apparently worthy purpose of relieving pain and fever in their livestock. Unfortunately, vultures scavenging on livestock carcasses accumulated large quantities of the drug and promptly died of renal failure. Over a 14-year period, populations of three vulture species plummeted by between 96.8 and 99.9 percent.

Losing these efficient scavengers meant livestock carcasses often got left in the open to rot. It was one of those "ecosystem services" — manufacturing oxygen, soaking up carbon dioxide, preventing floods, taking out the garbage — that species generally provide unnoticed, until they stop. But the impacts went well beyond the stench, according to a 2008 article in Ecological Economics. Moving into the niche vacated by the vultures, feral dog populations boomed by up to 9 million animals over the same period. Dog bites and the incidence of rabies in humans also increased, and the authors conservatively estimated that an additional 48,000 people died during the 14-year period as a result. Calculating the bottom-line worth of what we get from the natural world is notoriously difficult. But even pricing lives at a fraction of developed world values, the near-total loss of three insignificant vulture species has so far cost India an estimated $24 billion.

Now Meera Subramanian has a first-hand report in the Virginia Quarterly Review. These paragraphs near the end of the article seemed particularly poignant and powerful to me:

I realized as I spoke with Rahmani that I had come to India looking for an eco-catastrophe. Though the vulture is the unloveliest of creatures, though few cared for them while they were here nor notice that they are missing, their absence has left a void. There is a physical abyss that is filling with dogs that can be ferocious, and a spiritual vacuum that is forcing questions of adaption for the most orthodox of India's Parsis.

Yet it didn't feel apocalyptic to me. Maybe all of us, whether guided by God or by science, secretly want to be the ones living in the end times, as though it bestows some epic importance upon our little lives. But what if there is no ultimate annihilation, but instead a million daily deaths, literal or figurative, that no one quite notices? The vultures' disappearance is catastrophic, yes, but the ability to adapt is stunning. Or terrifying. Or both. No matter how bad things get, how many species get wiped from the earth in humanity's steady march of population and progress, the living go on. Those species that disappear are erased from the bio-narrative of the planet and forgotten within a generation that only knows of what came before through chance encounters at museum exhibits, a grandmother's knee, or a picture on a computer screen. Already, there are children turning into teenagers in India who have never seen a vulture, though their parents knew skies filled with swirling kettles of the scavengers for most of their lives. With the vultures becoming functionally extinct in under a decade, India's ecology has shifted and the habits of her people, whether farmers or skinners or Parsi priests, have yielded in transition. What if we adapt too easily?

This is what Rahmani was suggesting.

"I wish we were not so flexible. We're like pests. We can live in every type of environment, from Alaska to Namibia. We're omnivorous. We're like cockroaches, rats, and bandicoots," he said.

"You have seen the slums," the biologist continued. "Look at the horrible conditions we can live under and still have reproductive success."

He leaned back in his chair and the continuous insistent blast of car horns drifted up from the street, filling the space between his words.

"No other species has such a huge tolerance. For the earth, that is the unfortunate part. If we had a very narrow tolerance of pollution and food and all these things, maybe we would take more care of the earth."

Take a look at the full article here.