Richard Conniff's Blog, page 101

November 4, 2011

Built for Singing Duets

That old slogan "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle" always struck me as not nearly as clever as its admirers seemed to think. The truth, often annoying, sometimes delightful, is that women and men need each other like a fish needs a school.

Or, maybe, like birds need a flock. Here's a new study published yesterday in Science:

Long-married human couples may finish each others' sentences, but the plain-tailed wrens of the Andes take things a step further. Male and female wrens sing intimate duets in which they alternate syllables so quickly it sounds like a single bird is singing. New research shows that the brains of both the male and female wrens actually process the entire duet, not just each bird's own contribution. These findings are surprising because researchers have generally assumed that the brain activity of each songbird would be largely devoted to that bird's own singing role. Eric Fortune and colleagues recorded the wrens as they sang while hiding in the bamboo forests on Ecuador's Antisana volcano. Analyzing these recordings, the researchers learned that the female birds seem to establish the timing of the song and that males, but not females, make occasional mistakes during singing. Next, the researchers recorded the brain activity in the birds' song center while playing back recordings of bird duets as well as solos. The brain neurons responded most vigorously to the duets, suggesting that certain brain circuits — which are shared by humans — are primed for cooperation.

And here's an account of the study from Newswise:

The brain was built for cooperative activity, whether it be dancing on a television reality show, constructing a skyscraper or working in an office, according to a study led by Johns Hopkins behavioral neuroscientist Eric Fortune and published in the Nov. 4 issue of the journal Science."What we learned is that when it comes to the brain and cooperation, the whole is definitely greater than the sum of its parts," said Fortune, of the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. "We found that the brain of each individual participant prefers the combined activity over his or her own part."

In addition to shedding light on ourselves as social and cooperative beings, the results have important implications for engineers who want to be able to program autonomous robots to work effectively as teams in settings such as bomb squads and combat.

But Fortune's work didn't involve androids or take place on a battlefield. Instead, he and his team took to the cloud forests of Ecuador, on the slopes of the active Antisana Volcano. Why? It's one of the only places in the world where you can find plain-tailed wrens. These chubby-breasted rust-and-gray birds, who don't fly so much as hop and flit through the area's bamboo thickets, are famous for their unusual duets. Their songs — sung by one male and one female — take an ABCD form, with the male singing the A and C phrases and the female (who seems to be the song leader) singing B and D.

"What's happening is that the male and female are alternating syllables, though it often sounds like one bird singing alone, very sharply, shrilly and loudly," explained Fortune, who spent hours hacking through the thick bamboo with a machete, trying to catch the songbirds in nets. "The wrens made an ideal subject to study cooperation because we were easily able to tape-record their singing and then make detailed measurements of the timing and sequences of syllables, and of errors and variability in singing performances."

The team then captured some of the wrens and monitored activity in the area of their brains that control singing. They expected to find that the brain responded most to the animal's own singing voice. But that's not what happened.

"In both males and females, we found that neurons reacted more strongly to the duet song — with both the male and female birds singing — over singing their own parts alone. In fact, the brain's responses to duet songs were stronger than were responses to any other sound," he said. "It looked like the brains of wrens are wired to cooperate."

So it's clear that nature has equipped the brains of plain-tailed wrens in the Andes of Ecuador to work cooperatively and to prefer "team" activities to solo ones. But what does that have to do with people?

"Brains among vertebrate animals — frogs, cats, fish, bears and even humans — are more similar than most people realize," Fortune said. "The neurotransmitter systems that control brain activity at the molecular level are nearly identical among all vertebrates and the layout of the brain structures is the same. Thus, the kinds of phenomena that we have described in these wrens is very relevant to the brains of most, if not all, vertebrate species, including us humans."

CITATION: "Neural Mechanisms for the Coordination of Duet Singing in Wrens," by E.S. Fortune; D. Li; G.F. Ball at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD; E.S. Fortune; C. Rodriguez at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador in Quito, Ecuador; M.J. Coleman at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, CA; M.J. Coleman at Pitzer College in Claremont, CA; M.J. Coleman at Scripps College in Claremont, CA.

November 1, 2011

Your Halloween Costume for Next Year

Arizona State University sponsors an annual Ugly Bug contest. Below is one of this year's contenders, but you can check out the competition and cast your vote here:

[image error]

A flower beetle showing its pretty face. (Therry The and Marilee Sellers/Northern Arizona University)

Mommy, Who's for Dinner Tonight?

Natalie Angier writes today about animal cannibalism, starting with research by Richard Shine at the University of Sydney in Australia about cane toad tadpoles gobbling up cane toad eggs:

Significantly, the tadpoles weren't simply hungry for a generic omelette. Reporting in the journal Animal Behaviour, Dr. Shine and his co-workers showed that when given a choice between cane toad eggs and the similar-looking egg masses of other frog species, Rhinella tadpoles overwhelmingly picked the cannibal option. Oh, little cane toads lacking legs, how greedily you snack on pre-toads packed in eggs!

Life after metamorphosis brought scant relief from fraternal threats. The scientists also demonstrated that midsize cane toads wriggle digits on their hind feet to lure younger cane toads, which the bigger toads then swallow whole. "A cane toad's biggest enemy is another cane toad," Dr. Shine said. "It's a toad-eat-toad world out there."

Rhinella's brutal appetite is among a string of recent revelations of what might be called extreme or uncanny cannibalism, when one animal's determination to feed on its fellows takes such a florid or subversive turn that scientists are left, as Mark Wilkinson of the Natural History Museum in London put it, "gobsmacked" by the sight.

There are males that demand to be cannibalized by their lovers and males that seek to avoid that fate by stopping midcourtship and hammily feigning rigor mortis. There are mother monkeys that act like hipster zombies, greeting unwanted offspring with a ghoulish demand for brains; and there are infant caecilians — limbless, soil-dwelling amphibians — that grow fat by repeatedly skinning their mother alive.

In the past, animal cannibalism was considered accidental or pathological: Walk in on a mother rabbit giving birth, and the shock will prod her to eat her bunnies. Now scientists realize that cannibalism can sometimes make good evolutionary sense, and for each new example they seek to trace the selective forces behind it.

Why do cane toad tadpoles cannibalize eggs? Researchers propose three motives. The practice speeds up maturation; it eliminates future rivals who, given a mother toad's reproductive cycle, are almost certainly unrelated to you; and it means exploiting an abundant resource that others find toxic but to which you are immune.

"We're talking about a tropical animal that was relocated to one of the driest places on earth," Dr. Shine said. "Cannibalism is one of those clever tricks that makes it such a superb colonizer and a survival machine."

You can read the full article, in which she describes male black widow spiders being eaten by the females after sex as "arachinirvana" here. I think it would be nerve-wracky-nirvana, no?

[image error]

[image error]

October 28, 2011

Biomimicry and Bullet Trains

The BBC has a roundup of some of the ways the natural world is shaping industrial design:

For instance, a Canadian firm Whirlpower mimics humpback whale flippers and uses the principle on wind turbines and fans, reducing the drag and increasing the lift.

A paint company Lodafen applies the lotus effect, mimicking the shape of the bump on a lotus leaf.

Lotus leaves are self-cleaning – they have tiny bumps that help remove the dirt when it rains.

Lodafen uses the principle in architecture designs – and in Europe, there are more than 350,000 buildings that have this kind of paint.

The design of the fastest train in the world, Shinkansen bullet train in Japan, was inspired by the beak of a kingfisher."And of course the high-speed train, Shinkansen bullet train in Japan – it's the fastest train in the world, traveling 200 miles per hour.

"Instead of having a rounded front, it has something that looks like a beak of a kingfisher, a bird that goes from air to water, one density of medium to another," she adds.

You can read the full article here.

[image error]

[image error]

October 20, 2011

Fighting Back in the New War on Rhinos

Here's the story I reported from South Africa earlier this year. It's now out in the November Smithsonian:

Johannesburg's international airport is an easy place to get lost in the crowd, and that's what a 29-year-old Vietnamese man named Xuan Hoang was hoping to do one day in March last year—just lie low till he could board his flight home. The police dog sniffing down the line of passengers didn't worry him; he'd checked his baggage through to Ho Chi Minh City. But behind the scenes, police were also manning the x-ray scanners on flights to Vietnam, believed to be the epicenter of a new war on rhinos. And when Hoang's bag appeared on the screen, they saw the unmistakable shape of rhinoceros horns—six of them, weighing more than 35 pounds and worth up to $500,000.

Investigators suspected the contraband might be linked to a poaching incident a few days earlier on a game farm in Limpopo Province, on the country's northern border. "We have learned over time, as soon as a rhino goes down, in the next two or three days the horns will leave the country," said police Col. Johan Jooste of South Africa's national priority crime unit, when I interviewed him recently in Pretoria.

The Limpopo rhinos had been killed in a "chemical poaching," meaning that hunters, probably traveling by helicopter, shot them with a dart gun loaded with an overdose of veterinary tranquilizers. As the price of rhino horn has soared, said Jooste, a short, thickly-built bull of a cop, so has the involvement of sophisticated criminal syndicates.

"The couriers are like drug mules, specifically recruited to come into South Africa on holiday. All they know is that they need to pack for one or two days. They come in here with minimal contact details, sometimes with just a mobile phone, and they meet with guys providing the horns. They discard the phone so there's no way to trace it to any other people."

Police were not sure they would be able to send Hoang away for serious jail time, much less get to the professionals who had hired him. South African courts often require police not just to catch someone smuggling rhino horns, but actually connect the horns to a specific poaching incident. "In the past," said Jooste, "we needed to physically fit a horn on a skull to see if we had a match. But that was not always possible, because we didn't have the skull, or it was cut too cleanly."

Taking the sample for DNA analysis

Police sent the horns confiscated at the airport to Cindy Harper, head of the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of Pretoria. Getting a match with DNA testing had never worked in the past. Rhino horn consists of a substance like compressed hair, and conventional wisdom said it did not contain the type of DNA needed for precise individual identifications. But Harper had recently proved otherwise. In her lab a technician applied a conventional portable drill to each horn, sending up little ribbons of soft gray tissue that wrapped around a sterilized drill bit. The technician then pulverized and liquefied these tissue samples, and ran extracts through what looked like a battery of fax machines.

Two of the horns confiscated at the airport turned out to be a DNA match with the rhinos killed on the Limpopo game farm. The odds of another rhino having the same DNA were one in millions, according to Harper, and on a continent with only about 25,000 rhinos in total, that constituted foolproof evidence. A few months later, a judge sentenced Hoang to 10 years in prison. It was a rare victory in a violent and rapidly worsening fight to save the rhino.

###

Until recently, the epidemic rhino poaching of the late twentieth century seemed to have come under control. Back then, tens of thousands of animals were slaughtered and whole countries stripped of rhinos, largely to supply horns for use as traditional medicines in Asia, and as dagger handles in the Middle East. But in the 1990s, under strong international pressure, China removed rhino horn from the list of traditional medicines approved for commercial manufacturing, and Arab countries began to promote synthetic dagger handles. At the same time, African nations bolstered their rhino protection, and the combined effort seemed to reduce poaching to a tolerable minimum.

But that peaceful interlude ended abruptly in 2008, when rhino horn suddenly began to command prices beyond what anyone had ever seen–or even imagined. Since then, poaching of rhinos, and trade in their horns, has gone out of control, in ways that at times border on the bizarre. Police have reported more than 30 antique rhino horn thefts this year alone from museums, auction houses, and antiques dealerships in Europe, and at an auction in Moberly, Missouri, bidding for the antique horns of a single white rhino hit $125,000.

But most of the poaching is happening in South Africa, where the very system that helped build up the world's largest rhino population is now making those rhinos more vulnerable. Legalized trophy hunting of rhinos, supposedly under strict environmental limits, has always been a key part of rhino management there: The hunter pays a trophy fee, typically about $40,000 for a white rhino. The fees give game farmers an incentive to breed rhinos and keep them on their property. That also creates a market for national parks to sell surplus rhinos, earning income to help pay for rhino conservation.

But suddenly the price of rhino horn was so high that the fees became just a minor cost of doing business. Tourists from Asian nations with no history of trophy hunting began showing up for multiple trophy hunts in a year. In one recent case, they even hired Asian prostitutes to pose as hunters—and provide their passports to make export of the trophies seem legal. And wildlife professionals began to cross the fine line from trophy hunting rhinos to poaching them.

Vietnam seems to be the chief culprit in the new rhino horn trade. In Pretoria, an investigative news team filmed the first secretary of the Vietnamese mission accepting a contraband rhino horn and placing it in the trunk of her car on the street outside the embassy; a Vietnamese trade attaché was also implicated in a separate incident. Investigators from TRAFFIC, which monitors international wildlife trade, traced the sudden spike in demand to a rumor that rhino horn had miraculously cured a V.I.P. in Vietnam of terminal liver cancer. In traditional Asian medicine, rhino horn is credited only with relatively humble effects like relieving fever and lowering blood pressure– claims medical experts have debunked. (Despite Western lore, rhino horn has never been regarded as an aphrodisiac.) But fighting a phantom miracle cure was almost impossible. "If it was a real person, we could find out what happened and maybe demystify it," said Tom Milliken of TRAFFIC. But no such person has turned up. Meanwhile, poaching of rhinos has soared across the continent, and South Africa is on track to lose 400 rhinos this year, up from just 13 in 2007.

###

The struggle to save the African rhinoceros has been in some ways a remarkable success story, until now. Scientists generally count two rhino species, black and white, in Africa, and three species in Asia. Because of intensive management schemes, both African species were actually increasing in number over the past 15 years, even as Asian rhino populations continued to plummet. To find out how that's happened, and what may lie ahead, I set out one daybreak not long ago to look for rhinos at Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park (that first word is pronounced shla-shloo-ee), in KwaZulu-Natal province, on South Africa's eastern coast.

Now a 370-square-mile provincial park, Hluhluwe-Imfolozi is beautiful country, and said to have been a favorite hunting ground for Shaka, the nineteenth-century Zulu warrior king. Broad river valleys divide the rolling highlands, and dense green scarp forests darken distant slopes.

White rhinos once occurred in pockets across the length of Africa, from Morocco to the Cape of Good Hope. But because of relentless hunting and colonial land-clearing, there were no more than a few hundred individuals left in southern Africa by the end of the nineteenth century, and the last known breeding population was here. That remnant population was the reason colonial conservationists set this land aside in 1895 as Africa's first protected conservation area.

Jed Bird and a white rhino

My guide was Jed Bird, a 27-year-old with an easy-going manner and a rugby player's solid build. Almost before we started, he stopped his pickup truck to check out a scraping at the side of the road. "There was a black rhino here," he said. "Obviously a bull. You can see the vigorous scraping of the feet. Spreads the dung. Not too long ago." He imitated a rhino's stiff-legged kicking. "It pushes up the scent. So other animals will either follow or avoid him. They have such poor eyesight, you wonder how they find each other. This is their calling card."

You might also wonder why they bother. The orneriness of rhinos is so proverbial that the correct word for a group is not a herd, but a crash of rhinos. "The first time I saw one I was a four-year-old in this park. We were in a boat, and it charged the boat," said Bird. "That's how aggressive they can be." Bird, who was thrilled, now makes his living keeping tabs on the park's black rhinos, and also sometimes working by helicopter to catch them for relocation to other protected areas. "They'll charge helicopters," he added. "They'll be running and then after a while, they'll say, 'Bugger this,' and they'll turn around and run toward you. You can see them actually lift off their front feet as they try to have a go at the helicopter."

But this fierce reputation can also be misleading. Up the road a little later, Bird pointed out some white rhinos a half-mile off, and a few black rhinos resting nearby, placid as cows in a Constable painting of the British countryside. "I've seen black and white rhino lying together in a wallow almost bum-to-bum," he said. "A wallow's like a public facility. They sort of tolerate one another." After a moment, he added, "The wind is good." That is, it was blowing our scent away from them. "So we'll get out and walk." From behind the seat, he brought out a .375 rifle, the minimum caliber required by the park for wandering near big unpredictable animals, and we set off into the head-high acacia.

The peculiar appeal of rhinos is that they seem to have lumbered straight out of the Age of Dinosaurs. They are massive creatures, second only to elephants among modern land animals, with folds of thick flesh that look like protective plating. A white rhino can stand six feet at the shoulders and weigh 6,000 pounds, with a horn on its nose up to six feet in length, and a slightly shorter horn just behind. (The dinosaurian-sounding name rhinoceros means "nose horn.") Its eyes are dim little poppy seeds low down on the sides of its great skull. But the big feathered ears are acutely sensitive, as are its vast snuffling nasal passages. The black rhino is smaller, weighing up to about 3000 pounds, but compensates by being more quarrelsome.

Both black and white rhinos are actually shades of gray; the big difference between them has to do with diet, not skin color. White rhinos are grazers, their heads almost always down on the ground, their wide, straight mouths constantly mowing the grass. Hence they are sometimes known as square-lipped rhinos. Black rhinos, by contrast, are browsers. They snap off branches with the chisel-like cusps of their cheek teeth and swallow them thorns and all. "Here," Bird said, indicating an acacia scissored off at a 45-degree angle. "Sometimes you're walking and if you're quiet you can hear them browsing 200 or 300 meters ahead. Whoosh, whoosh." Blacks, also known as hook-lipped rhinos, have a powerful prehensile upper lip for stripping foliage from bushes and small tree branches. The lip dips down sharply in the middle, as if the rhino had set out to grow an elephant trunk but ended up becoming The Grinch instead.

We followed along the bent grass the rhinos had laid down in passing, crossed through a deep ravine, and came up into a clearing. The white rhinos were moving off, with the tick-eating birds called oxpeckers riding sidesaddle on the backs of their necks. But the black rhinos had settled down for a rest. "We'll go into those trees there, then wake them up and get them to come to us," Bird said. The ideas made my eyes widen. We headed out in the open, with nothing between the rhinos and us except a few hundred yards of low grass. Then the oxpeckers gave out their alarm call—"Chee-cheee!"—and one of the black rhinos stood up and seemed to stare straight at us. "She's very inquisitive," Bird said. "I train a lot of field rangers and at this point they're panicking saying, 'It's got to see us,' and I say, 'Relax, it can't see us.' You just have to watch its ears."

Coming to call on us

The rhino settled back down and we made it to a tree with lots of knobs for hand- and foot-holds, where elephants had broken off branches. Bird leaned his rifle against another tree and we headed up. Then he started blowing out his cheeks and flapping his lips in the direction of the rhinos. When he switched to a soft high-pitched cry, like a lost child, a horn tip and two ears rose above the seed heads of the grass and swung in our direction like a periscope. The rest of the rhino soon followed, lifting up ponderously from the mud. As she ambled over through the grass, Bird identified her from the pattern of notches on her ears as C450, a pregnant female. Her flanks were more blue than gray, glistening with patches of dark mud. She stopped when she was about eight feet from our perch, eyeing us sideways, curious but also skittish. Her nostrils quivered and the thick folds of flesh above them seemed to arch like eyebrows, inquiringly. Then suddenly her head pitched up as she caught our alien scent. She turned and ran off huffing like a steam engine.

Mama coming a little too close

A few minutes later, undeterred, two other black rhinos, a mother-daughter pair, came over to investigate. This time, they nosed into our small stand of trees. Bird hadn't figured they would come so close, but now he worried that one of them might bump into his rifle. The idea of a rhino shooting humans had a certain man-bites-dog logic, but Bird spared us the poetic justice by dropping his hat down in front of the mother to send her on her way.

###

Rhinos do not breed like rabbits. Pregnancy lasts 16 months, and a mother may tend her calf for up to four years after birth. Even so, conservation programs have managed to produce a steady surplus of rhinos in recent decades. The challenge has been figuring out where to put the extras once a population grows beyond what a fenced-in park or game farm can support. It is particularly critical now for black rhinos. Knocked down by the poaching crisis of the 1990s to fewer than 2500 animals, the population has rebuilt to about 4000. Conservationists hope to accelerate that rate of growth as a buffer against further poaching, and their model is what Hluhluwe-Imfolozi did for white rhinos beginning in the 1950s.

South Africa was then turning itself into the world leader in game capture, the tricky business of catching, transporting, and releasing big, dangerous animals. Rhinos were the ultimate test—6000 pounds of anger in a box. As the remnant population of white rhinos at Hluhluwe-Imfolozi recovered, it became the seed stock for repopulating the species in parks in Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and other countries. In South Africa itself, private landowners also played a key part in rhino recovery, on game farms geared either to tourism or, under strict regulation, to trophy hunting. The result is that there are now more than 17,000 white rhinos in the wild, plus another 3000 in captivity, and the species is no longer on the threatened list.

Doing something like that with black rhinos is more challenging today, because human populations have boomed, rapidly eating up open space. Ideas about what rhinos need have also changed. Not too long ago, said Jacques Flamand of the World Wildlife Fund, conservationists thought an area of about 23 square miles—the size of Manhattan Island — was enough for a founding population of a half-dozen black rhinos. But recent research says it takes 20 founders to be genetically viable, and they need about 77 square miles of land. Many rural landowners in South Africa want black rhinos for their game farms and safari lodges. But few of them control that much land, or can afford to buy the rhinos in any case: Black rhinos sold at wildlife auctions, until the practice was recently suspended, for about $70,000 apiece.

So Flamand has been working with KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Wildlife, the provincial park service, to cajole landowners into a novel partnership: If they agree to open up their land and meet stringent security requirements, KZN will introduce a founding population of black rhinos and split ownership of the offspring. In one case, 19 neighbors pulled down the fences dividing their properties. They also had to build a better exterior fence to protect the perimeter against poachers. "Security has to be good," said Flamand. "We need to know if the field rangers are competent, how they are equipped, how organized, how distributed, whether they are properly trained." Over the past six years, the range for black rhinos in KwaZulu-Natal has increased by a third, he said, allowing the addition of six new populations with a total of 98 animals.

The program can seem a bit like a spy agency moving fugitives from one safe house to the next in hostile terrain–big, belligerent fugitives, at that, and not too bright, either. Conservationists have had to learn to think more carefully about which animals to move, and how to move them. In the past, parks sometimes transferred surplus male rhinos without bothering to include females as potential mates. It was a recipe for trouble (predictably, you would think). The males got mad–or madder–and often killed one another. But moving mother-calf pairs was perilous, too. The standard practice of calming captive rhinos by holding them in bomas, or corrals, for weeks at a time just caused the moms to become frustrated and restless. Accidentally or otherwise, more than half the calves died, according to Wayne Linklater, lead author of a new study on black rhino translocations. Mother-calf pairs now generally move directly to their new homes instead.

Catching pregnant females, another common approach, also caused problems. The stress of capture could lead to miscarriages, sometimes resulting in an excess of male or female offspring, with unfortunate effects on future reproduction. The emphasis on moving a lot of young females may also have depleted the literal motherlode, the breeding population protected within Hluhluwe-Imfolozi. "We're left with a whole lot of grannies in the population, and not enough breeding females," said park ecologist David Druce.

Researchers have now come to recognize that understanding the social nature of black rhinos is the key to getting them out, and reproducing, in new habitats: A territorial bull will tolerate a number of females and some adolescent males in his neighborhood. So translocations now typically start with one bull per water source. After he has walked around a bit and settled in, the females follow, and then the younger males. To keep territorial bulls separated during the crucial settling process, researchers have experimented with distributing rhino scent strategically around the new habitat, creating "virtual neighbors." Using a bull's own dung didn't work. (They are at least bright enough, one researcher suggested, to think: "That's my dung. But I've never been here before.") Researchers are still trying to determine whether using dung from other rhinos is a way to communicate that this is suitable habitat and also that wandering into neighboring territories could be risky.

The release itself has also changed. In the macho game capture culture of the past, it was like a rodeo: A lot of vehicles gathered around to watch. Then someone opened the crate and the rhino came busting out, like a bull entering an arena. Sometimes it panicked and ran till it hit a fence. Other times it charged the vehicles, often as the nature documentary cameras rolled. "It was good for television, but not so good for animals," said Flamand. Game capture staff now practice "soft releases" instead. The rhino is sedated in its crate, and all the vehicles move away. Someone administers an antidote and also backs off, leaving the rhino to wander out and explore its new neighborhood at leisure. "It's very calm. It's boring, which is fine."

If these new rhino habitats are like safe houses, the renewed threat of poaching means they can be astonishingly wired safe houses. The animals are often individually identified (with ear notches), implanted with RFID microchips (for radio frequency identification), camera-trapped, geo-tracked, registered in a genetic database, and otherwise monitored by every available means short of a breathalyzer.

Early this year, for instance, Somkhanda Game Reserve, an hour or so up the road from Hluhluwe-Imfolozi, installed a system that requires implanting a GPS device the size of a D cell battery in the horn of every rhino. (Somkhanda is a partner in the KZN black rhino program, and the first owned by a black African community.) The device communicates with receivers mounted on utility poles around the reserve, transmitting not just an animal's exact location but also every movement of its head, up-and-down, back-and-forth, side-to-side.

A movement that deviates suspiciously from the norm causes an alarm to pop up on a screen at a security company 250 miles away in Johannesburg, and the company relays the animal's location to field rangers back at Somkhanda. "It's a heavy capital outlay," said Simon Morgan of Wildlife ACT, which works with conservation groups on wildlife monitoring, "but when you look at the cost of rhinos, it's worth it. We have made it publicly known that these devices are out there. At this stage, with nobody else doing it, that's enough to make poachers go elsewhere."

##

A few months after the Vietnamese courier Xuan Hoang went to prison, police conducted a series of raids in Limpopo Province. Frightened by continued rhino poaching on their land, angry farmers there had tipped off investigators about a helicopter they had seen flying low over their properties. Police traced the chopper and arrested Dawie Groenewald, a former police officer, and his wife Sariette, who had become game farmers and safari operators in the area. They were charged with being kingpins of a poaching ring that traded in contraband horns and also targeted the rhinos on nearby game farms. But what shocked neighbors more was the allegation that two local veterinarians, people they had trusted to care for their animals, had been helping to kill them instead. Rising prices for rhino horn, and the prospect of instant wealth, had apparently shattered a lifetime of ethical constraints.

Conservationists were shocked, too. One of the veterinarians had been a familiar face at wildlife auctions where parks parcel out their surplus animals. He had been a go-between for the Groenewalds, who purchased 36 rhinos from Kruger National Park in 2009. Investigators later turned up a mass grave with 20 rhino carcasses on the Groenewald farm. The conspirators were allegedly responsible for the killing of hundreds of rhinos. Twelve people have been charged in the case so far, and the trial is now scheduled for next spring.

Illegal trafficking in rhino horn does not seem to be confined to one criminal syndicate, or a single outlaw game farm. "A lot of people are gobsmacked by how pervasive that behavior is throughout the industry," said TRAFFIC's Milliken. "People are just blinded by greed—your professional hunters, your veterinarians, the people who own these game ranches. We have never seen this level of private sector complicity with Asian wildlife gangs."

Like Milliken, most conservationists believe trophy hunting can be a legitimate contributor to conservation of rhinos. But now they are also seeing that hunting has created a moral gray zone. The system depends on harvesting a limited number of rhinos under permits issued by the government. But when the price is right some trophy hunting operators apparently find that they can justify killing any rhino. Obtaining permits—or even ownership—becomes a technicality. Rules designed to keep the trophy hunting system honest—for instance, the requirement that the trophy horn and head be exported intact—are merely inconvenient. In South Africa, the epidemic of poaching by wildlife professionals has produced widespread outrage with the current system, particularly when the Groenwalds, out on bail, briefly received permits for additional rhino hunts. The national government is now considering a moratorium on trophy hunting of rhinos. But hunting advocates said that would just make the illegal horn trade more profitable.

The one hopeful sign, said Milliken, is that prices seem to have spiked too quickly to be attributable to increased demand alone. That is, the current crisis might be a case of the madness of crowds—an economic bubble inflated by speculative buying in Asia. If so, like other bubbles, it will eventually go bust.

For now, though, the rhinos continue to die. At Hluhluwe-Imfolozi, poachers last year killed three black rhinos and 12 whites. To San-Mari Ras, a district ranger there, it is like robbing from Noah's Ark: "We have estimated that what we are losing would basically overtake the birth rate in the next two years, and populations will start to drop down." That is, the motherlode may no longer have any seed stock to send to other new habitats.

From the floor of her office, she picked up the skull of a black rhino calf with a neat little bullet hole into its brain. "They will take a rhino horn even at this size," said Ras, spreading her thumb and index finger. "That's how greedy the poachers can be."

San Mari-Ras and poaching victim

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 12, 2011

The Sociopathological Architect

Ponti's Prison

I don't normally write about architecture here because it seems off-topic. But buildings certainly change our behavior, and I think about that every time I go near one.

So this morning I went looking for the Denver Art Museum and instead found what I took to be a prison, the museum's North Building, opened in 1971. The woman at the desk inside explained that Italian architect Gio Ponti had intended it to look like a castle, complete with slit windows, because he thought art needed to be locked up and safeguarded. "If a museum has to protect works of art," he pronounced, "isn't it only right that it should be a castle?" The original design actually included a moat. Ponti's main entrance, now closed off, is a cylinder that feels like an airlock between alien worlds, art within, drooling masses outside.

Once you manage to find your way in, oddly, the interior is incredibly homey, with warm colors on the walls, and easy chairs arranged in little groupings for people to sit and chat, or just contemplate the art before them. I have rarely felt more comfortable in a museum.

Libeskind's shipwreck

So then I wandered over to the museum's new addition, named after some benefactor and designed by Daniel Libeskind. If Ponti thought it was his job to shut out the city, Libeskind seems to think his job is to make war on it. His building is a jumble of jagged edges, threatening everything around it. Instead of inviting you to come in, it roars at you to keep your distance: Don't touch me. It's also covered in highly reflected metal, so you can barely even look at it by day. Inside, function is similarly distorted by form. The walls and ceilings everywhere skew toward you or away from you, making it hard to figure out where you are in the building, and where you should be going next. I found it extremely difficult to just stand still and look at the art, because even standing still, I felt motion sickness coming on. Libeskind clearly wants us to know that he is an artist, indeed, the artist, above all others, not merely someone who sets the scene.

God save us from such architects.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

October 8, 2011

Seahorses in the Sewer

Eat your words, Boris Johnson. You pronounce nature dead and, boom, she comes roaring back. Last week, Johnson, who is London's mayor, was complaining about the state of the River Thames. This week, seahorses turn up not just in the Thames, but practically waggling their tails at Traitor's Gate. Here's the report from The Independent:

Eat your words, Boris Johnson. You pronounce nature dead and, boom, she comes roaring back. Last week, Johnson, who is London's mayor, was complaining about the state of the River Thames. This week, seahorses turn up not just in the Thames, but practically waggling their tails at Traitor's Gate. Here's the report from The Independent:Seahorses, the distinctive horse-headed small fish typically found in tropical seas and on coral reefs, are thought to be breeding in the River Thames in London, the Environment Agency announced yesterday.

A juvenile short-snouted seahorse, Hippocampus hippocampus, was recently found in the river at Greenwich and may be evidence of a breeding colony, the agency said.

Growing up to 15cm (six inches) long, the species is more commonly found in the waters of the Mediterranean and Canary Islands, although it is sometimes encountered around the British coasts, especially in the south and in the Thames Estuary. The last sighting of a seahorse in the Thames was at Dagenham in 2008 – much further down river than the one caught at Greenwich, which is only five miles from Westminster.

"The seahorse we found was only five centimetres long, a juvenile, suggesting that they may be breeding nearby," said Emma Barton, Environment Agency Fisheries Officer."This is a really good sign that seahorse populations are not only increasing, but also spreading to locationswhere they haven't been seen before. We routinely survey the Thames at this time of year and this is a really exciting discovery.

"We hope that further improvements to water quality and habitat in the Thames will encourage more of these rare species to take up residence in the river."

The species adds to the growing numbers of wildlife returning to the Thames, which a survey in 1958 showed was "biologically dead", with no viable fish populations from Kew in the west to Greenwich in the East. But London's river has undergone a dramatic transformation, beginning with the secondary treatment of sewage in 1964, and it now supports more than 125 fish species such as eels, pike, sea bass, flounder and roach.

Last year the Thames was awarded the International Theiss River prize which celebrates outstanding achievement in river management and restoration.

Two of the world's 35 seahorse species have been found in British waters, the other being the long- snouted seahorse, Hippocampus guttulatus. Most of the remainder are found in tropical seas, and many of them are endangered, because they live in the

most vulnerable of marine habitats, the coastal environment – coral reefs, estuaries, mangrove swamps and seagrass beds – which are all being hard hit by pollution and coastal development.

They are also threatened by over-fishing, being targeted for use in traditional Asian medicine, as live pets and for the souvenir trade. Every year an estimated 30 million seahorses are traded by between 70 and 80 countries.

October 2, 2011

A Lesson for London from Milwaukee

London's Mayor Boris Johnson says his city is lapsing back to the Great Stink of 1858. The city's sewerage system, built for a city of 2.5 million people, cannot handle the present population of 8 million, and every time the skies add in just two millimeters–less than a tenth of an inch–of rain, the"Bazalgette Interceptors" break open and raw sewage pours into the river. Johnson writes:

London's Mayor Boris Johnson says his city is lapsing back to the Great Stink of 1858. The city's sewerage system, built for a city of 2.5 million people, cannot handle the present population of 8 million, and every time the skies add in just two millimeters–less than a tenth of an inch–of rain, the"Bazalgette Interceptors" break open and raw sewage pours into the river. Johnson writes:

In one of the crimes for which we are truly all guilty, society is now discharging an awful 50 million tons of raw sewage into the river in London alone, and unless we are bold in our plans, that figure will rise to 70 million tons in 10 years…

When Bazalgette designed his interceptors, in response to the Great Stink of 1858, he assumed that they would only kick into action in emergencies – truly torrential downpours of a kind that happen once or twice a year.

Now it happens 50 times a year, basically once a week. Johnson says the answer is massive infrastructure improvements, conceived and built with "neo-Victorian boldness":

That is why it is time to recognise that we can no longer rely on Victorian capital, and why Thames Water is right to be consulting on its proposed super-sewer, known as the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

Of course, it must construct this cloaca maxima in a way that minimises hassle for local people and avoids damage to riparian beauty spots. But the basic idea is excellent, and essential. At a depth of 75 metres – below the Tube and other excavations – and with a bore the width of three buses, this huge tunnel will run winding beneath the course of the Thames from Richmond to a series of vastly improved and upgraded East End sewage works … It is a breathtakingly ambitious project, on a scale that would have attracted the approval of Brunel and Bazalgette themselves.

But here's the lesson London needs to learn from Milwaukee: What Johnson, an Oxford man, calls the "cloaca maxima" approach doesn't work, no matter how big you build it. It may be necessary, but it's not enough. Instead of neo-Victorian thinking, what's needed is a little post-industrial creativity, to keep the rainwater from getting into the sewerage system in the first place. Here's what I wrote about it, sometime last year:

Planting trees might seem at first like an improbable tool for dealing with combined sewer overflows (CSOs)—a common problem in older cities where domestic wastes and stormwater run through the same pipes. Many cities now face federal deadlines—and huge construction costs—to stop such systems from spilling raw sewage into basements and waterways during rainstorms. The conventional engineered, or "gray," remedy is to build massive deep tunnels capable of retaining overflow, to be released gradually through municipal water treatment plants after the rain stops falling. But cities are now also pushing to prevent the water from getting into the system in the first place by using trees, green roofs and permeable pavements to sponge it up where rain falls.

In one typical case, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District has spent $4 billion over the past two decades on gray remedies, adding 494 million gallons of deep-tunnel storage. But when a major rainstorm hit late on a Saturday afternoon in June 2008, the runoff was on track to fill the entire system in just 56 minutes.

District managers had to divert combined wastes into area waterways and reserve the deep tunnels to retain separated household wastes, which also overflowed as the storm continued over the next three days. To prevent that kind of mess in the future, the district is now spending $300 million to preserve open space along local waterways. It also recently paid market prices to remove 75 homes in a downtown neighborhood, adding the land to a city park that doubles as a flood retention pond.

Likewise in Philadelphia, a 2009 study compared gray CSO prevention measures (adding more deep tunnels) with a green infrastructure approach that aimed to halve the runoff from existing impervious surfaces at roughly the same cost. Stratus Consulting, based in Boulder, Colo., estimated that the gray approach would produce $122 million in benefits over 40 years after subtracting construction costs. For the green alternative, the net benefits added up to $2.8 billion—more than 20 times as much—including improved property values, increased recreational opportunities and avoided heat-stress deaths.

Those kinds of numbers have attracted widespread interest. For instance, an innovative proposal from the Center for Neighborhood Technology in Chicago would fund tree planting and other green infrastructure programs with municipal bonds based on the projected increase in real estate values and tax revenues such programs produce. But there has been only cautious interest so far because it's unclear whether enforcement officials at the Environmental Protection Agency will accept green infrastructure as a tool for CSO prevention. Even so, Philadelphia recently launched the largest green infrastructure program in the country to transform the city over the next 20 years at a cost of $1.6 billion. The city is also adjusting its water and sewer fee structure so that commercial users pay, in part, based on a property's impervious surface area—a measure of stormwater runoff. Howard Neukrug, director of the city's Office of Watersheds, described the program as an attempt to "break down some of the barriers against nature and deal with rainwater where it lands." Despite reservations about the cost, The Philadelphia Inquirer summed up neighborhood response this way: "What's not to like about cleaner air, cooler houses and prettier streets?"

September 27, 2011

Meeting for a Drink in the Northwest Passage

Zak Smith is a lawyer working for the Natural Resources Defense Council on marine mammal protection. And–go figure–he knows how to write clearly. Smith posts a weekly roundup of whale news, and here's his latest:

Lots of news in the world of whales this week (or close to this week):

"Nice to meet you, we haven't seen your family in these parts in 10,000 years." This may have been the conversation when a male bowhead whale from the Greenland side of the Arctic mingled with a male bowhead whale from the Alaska side after they met north of the Canadian mainland in the fabled "Northwest Passage." The meeting was possible following the second lowest level of sea-ice extent recorded in the Arctic since 1979, one of the most obvious and potentially devastating effects (good bye polar bears) of global warming. Fossil evidence reveals that these two populations of bowhead whales have not been in contact for anywhere between 8,500 and 11,000 years. I'm sure they had a lot to catch up on. Maybe that is why the hung out in the same area for about 10 days.

Researchers have identified a "new" dolphin species – Burrunan Dolphin (Tursiops australis). Of course, the species is not new at all, with aboriginal people documenting their existence for over 1,000 years, but until recently the two resident populations of this species found in southeastern Australia were designated as members of already identified bottlenose dolphin species. Not so, according to Kate Charlton-Robb of Monash University. Ms. Charlton-Robb and her colleagues studied dolphin skulls and DNA to confirm that Burrunan Dolphin is unique. In their article, "A New Dolphin Species, the Burrunan Dolphin Tursiops australis sp. nov., Endemic to Southern Australian Coastal Waters," the scientists explained that "formal recognition of this new species is of great importance to correctly manage and protect this species," which is especially crucial given the proximity of the two small resident populations to major urban and agricultural centers. I say, "Welcome Burrunan Dolphin to the world of proper classification and good luck not going extinct (see below), you're going to need it."

Unfortunately Scotland's only resident pod of killer whales is doomed to extinctionafter failing to produce a single surviving calf in 20 years. While other killer whales visit Scottish waters, the nine whales left from this pod, John Coe, Floppy Fin, Comet, Aquarius, Nicola, Lulu, Moneypenny, Puffin, and Ocassus, make the waters off the west of Scotland their home year round. Scientists think pollution is to blame (no surprise there as whales store contaminants in their body fat, which is passed onto calves when feeding). And while nothing can help this pod, the scientists hope that restrictions will be put in place to limit contaminants in water, helping other whales avoid the same fate.

Of course, contaminants aren't the only threat whales face. Ship strikes are a serious threat to could lead to the local extinction of Bryde's whales in New Zealand's Hauraki Gulf. Last week a Bryde's whale died after being struck by a ship in the gulf. The necropsy showed sever trauma causing death, including 15 fractured vertebrae, broken ribs, and extensive bruising. Professor Mark Orams says, "If it continues to happen, we can potentially see a local extinction of the species in the Hauraki Gulf." Fortunately, there's a way to help these whales – imposing speed restrictions on commercial shipping vessels passing through the gulf on their way to port.

While no one knows what whales are saying to each other when they make their calls, scientists are trying to decipher the language of blue whales. Here's my guess as to what they are saying:

Whale 1: "Hey, did you hear about what's happening to killer whales in Scotland and Bryde's whales in New Zealand? What a mess."

Whale 2: "Yes, it's just awful. And did you hear what happened to Mike Minke? He was one of the 195 whales killed by Japan's whaling fleet this season in the northwest Pacific Ocean."

Whale 1: "Ugh."

But wait, aren't whales too dumb to realize what is going on? Apparently not. New evidence suggests that dolphins may comprehend mortality, grieving for their dead. The most recent evidence comes from a researcher, Joan Gonzalvo, who has observed heartbreaking behavior in dolphins. In one instance, a mother dolphin repeatedly lifted the corpse of her deceased newborn calf to the surface. According to Gonzalvo, "This was repeated over and over again, sometimes frantically, during two days of observation. The mother never separated from her calf…. [She] seemed unable to accept the death." Unfortunately, something tells me that whales have a lot more grieving to do.

Let's get back to the bright side; Narwhals are awesome. Check out this article that talks about Narwhals jousting for superiority in the summer months. It has great photos too. Amazing animals.

Meanwhile, this week in Wales…

Worlds still colliding…. Plans to build a 417-turbine windfarm, as big as the Isle of Wight, were revealed this week in Wales. The windfarm is supposed to be located in the Bristol Channel, covering a 257 square mile patch of the Channel, spanning 25 miles east to west. A spokesperson for the Porthcawl Environmental Trust expressed concern about the impacts the farm could have on the harbor porpoises, a marine mammal common in the Channel.

September 26, 2011

Edward Lear and his Birds

Early this year I wrote a piece for the New York Times about the close connection between nineteenth century nonsense verse and the story of global exploration and species discovery.

I wrote particularly about how Edward Lear, author of The Jumblies and other favorite children's books, got his start as an ornithological illustrator. So I am pleased to see this material on Lear from the web site BibliOdyssey. The author is a self-effacing Australian (a phrase that sounds as unlikely as self-effacing Texan) who is basically anonymous. He goes by the name Paul or Peacay, and thinks the attention should go to the work, by other people, that he is celebrating. Click through to savor some of Lear's lovely illustrations:

Lear's Parrots – The Prequel

Edward Lear Sketches of Parrots Relating to 'Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots' (1832), ca. 1830 (MS Typ 55.9). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

A selection of plates from Lear's published book can be seen in the following post from 2008: The Parrots.

That book is definitely one of my all-time favourite natural history publications; so I was particularly happy to discover Harvard's intriguing collection of preliminary sketches and practice lithographs by Lear.

To quote myself:

"The balance of critical opinion regards Lear's book on parrots to be the finest ever published on that bird family and among the greatest ornithological works ever produced.

It's not just because such an audacious project was successfully completed by so young a character, or that the subject matter was drawn so sensitively and with great scientific accuracy and naturalistic detail, but because the exceptional quality of Lear's plates – drawn, wherever possible, from living specimens – would significantly influence the work of two contemporary artists, John James Audubon and John Gould, perhaps the greatest ornithological illustrators of all time.

Both Audubon and Gould would employ Lear during the 1830s to assist in their projects and it was only failing eyesight that foreshortened Lear's bird illustrating career."

Note: Edward Lear was TWENTY YEARS OLD when his Parrot book was published!!

Lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo : ink, graphite and watercolour drawing. 45 x 30.9 cm.

Drawing cut-out and pasted on leaf.

Inscribed upper left:

"September 1830. Plyctolophus Sulphureus. from a living specimen at Bruton Street."

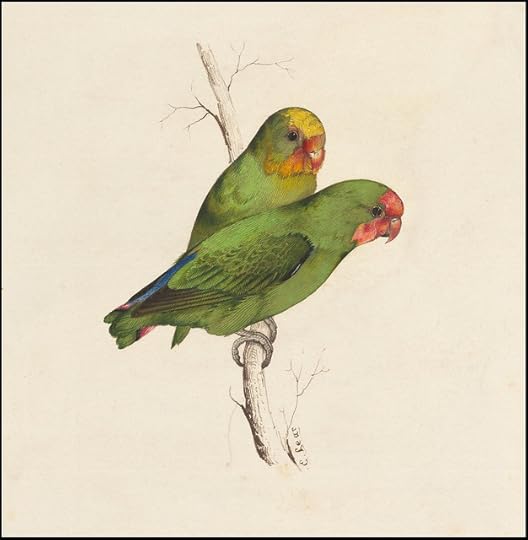

Two small green birds : hand-coloured lithograph

Macaw : graphite and watercolour drawing. 35.4 x 25.7 cm.

Two small parrots in foliage : ink and watercolour drawing. 37.2 x 55 cm.

Parrot head [red and yellow macaw] : graphite and watercolour drawing. 36.5 x 37 cm

Grey cockatoo : graphite and watercolour drawing. 42.8 x 31.6 cm.

Salmon-crested cockatoo : graphite and watercolour drawing. 54.7 x 36.6 cm.

Drawing for plate 2 in 'Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots' , 1832.

[Two supplemental pieces of paper [MS Typ 55.9 (22/25a), MS Typ 55.9 (22/25b)] were detached from the sheet for drawing 22 by Lear himself and affixed to drawing 25. One, with colour samples, overlaid the lower right corner of drawing 25; the other was used to extend the feathered crest of the cockatoo beyond the upper edge of the main sheet of drawing 25.]

Small parrot : hand-coloured lithograph. drawing. 55.4 x 36.4 cm.

Green parrot : ink, graphite and watercolour drawing. 33.7 x 29.2 cm.

Inscribed:

"Palaeornis Torquatus. Leila: living at Mr. Vigor's – Chester Terrace. drawn February 1831."

Parrot : graphite and watercolour on lithograph. 54.2 x 36.6 cm.

Inscribed upper left:

"Intended for P. Obscurus, alive at Bruton St. June 1830."

Green and red parrot : ink, graphite and watercolour drawing. 34.3 x 27.4 cm.