Richard Conniff's Blog, page 108

March 6, 2011

Our Built-In Propensity for Staring Down Rivals

Terburg

Our staring contests appear to be an instinctive dominance behavior passed down from our simian ancestors, though whether we glower or quickly turn away depends on individual tendencies to dominance or submission, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. They published their work in the journal Psychological Science. Here's part of the press release:

Imagine that you're in a bar and you accidentally knock over your neighbor's beer. He turns around and stares at you, looking for confrontation. Do you buy him a new drink, or do you try to outstare him to make him back off? New research … suggests that the dominance behavior exhibited by staring someone down can be reflexive.

Our primate relatives certainly get into dominance battles; they mostly resolve the dominance hierarchy not through fighting, but through staring contests. And humans are like that, too.

Psychologist David Terburg and his co-authors set out to test the standard assumption that staring for dominance is automatic for humans:

For the study, participants watched a computer screen while a series of colored ovals appeared. Below each oval were blue, green, and red dots; participants were supposed to look away from the oval to the dot with the same color. What they didn't know was that for a split-second before the colored oval appeared, a face of the same color

appeared, with one of three expressions–angry, happy, or neutral. The researchers were testing how long it took for people to look away from faces with different emotions. Participants also completed a questionnaire that reflected how dominant they were in social situations.

People who were more motivated to be dominant were slower to look away from angry faces, while people who were motivated to seek rewards gazed at the happy faces longer. In other words, the assumptions were correct—for people who are dominant, engaging in gaze contests is a reflex.

"When people are dominant, they are dominant in a snap of a second," says Terburg. "From an evolutionary point of view, it's understandable—if you have a dominance motive, you can't have the reflex to look away from angry people; then you have already lost the gaze contest."

By the way, that's a photo of Terburg at top, left, and my advice?

Buy him the beer.

March 3, 2011

Charlie Sheen and the Cookie Monster Test

The very public bad behavior of Charlie Sheen and fashion designer John Galliano–a future couple? … They have so much in common–reminds me that it's time to reprise this op-ed piece about why the rich and famous often act like such flaming idiots. It originally appeared in 2007 in the New York Times:

The very public bad behavior of Charlie Sheen and fashion designer John Galliano–a future couple? … They have so much in common–reminds me that it's time to reprise this op-ed piece about why the rich and famous often act like such flaming idiots. It originally appeared in 2007 in the New York Times:

THE other day at a Los Angeles race track, a comedian named Eddie Griffin took a meeting with a concrete barrier and left a borrowed bright-red $1.5 million Ferrari Enzo looking like bad origami. Just to be clear, this was a different bright-red $1.5 million Ferrari Enzo from the one a Swedish businessman crumpled up and threw away last year on the Pacific Coast Highway. I mention this only because it's easy to get confused by the vast and highly repetitious category "Rich and Famous People Acting Like Total Idiots." Mr. Griffin walked away uninjured, and everybody offered wise counsel about how this wasn't really such a bad day after all.

So what exactly constitutes a bad day in this rarefied little world? Did the casino owner Steve Wynn cross the mark when he put his elbow through a Picasso he was about to sell for $139 million? Did Mel ("I Own Malibu") Gibson sense bad-day emanations when he started on a bigoted tirade while seated drunk in the back of a sheriff's car? And if dumb stuff like this comes so easy to these people, how is it that they're the ones with all the money?

Modern science has the answer, with a little help from the poet Hilaire Belloc.

Let's begin with what I call the "Cookie Monster Experiment," devised to test the hypothesis that power makes people stupid and insensitive — or, as the scientists at the University of California at Berkeley put it, "disinhibited."

Researchers led by the psychologist Dacher Keltner took groups of three ordinary volunteers and randomly put one of them in charge. Each trio had a half-hour to work through a boring social survey. Then a researcher came in and left a plateful of precisely five cookies. Care to guess which volunteer typically grabbed an extra cookie? The volunteer who had randomly been assigned the power role was also more likely to eat it with his mouth open, spew crumbs on partners and get cookie detritus on his face and on the table.

It reminded the researchers of powerful people they had known in real life. One of them, for instance, had attended meetings with a magazine mogul who ate raw onions and slugged vodka from the bottle, but failed to share these amuse-bouches with his guests. Another had been through an oral exam for his doctorate at which one faculty member not only picked his ear wax, but held it up to dandle lovingly in the light.

As stupid behaviors go, none of this is in a class with slamming somebody else's Ferrari into a concrete wall. But science advances by tiny steps.

The researchers went on to theorize that getting power causes people to focus so keenly on the potential rewards, like money, sex, public acclaim or an extra chocolate-chip cookie — not necessarily in that order, or frankly, any order at all, but preferably all at once — that they become oblivious to the people around them.

Indeed, the people around them may abet this process, since they are often subordinates intent on keeping the boss happy. So for the boss, it starts to look like a world in which the traffic lights are always green (and damn the pedestrians). Professor Keltner and his fellow researchers describe it as an instance of "approach/inhibition theory" in action: As power increases, it fires up the behavioral approach system and shuts down behavioral inhibition.

And thus the Fast Forward Personality is born and put on the path to the concrete barrier.

The corollary is that as the rich and powerful increasingly focus on potential rewards, powerless types notice the likely costs and become more inhibited. I happen to know the feeling because I once had my own Los Angeles Ferrari experience. It was a bright-red F355 Spider (and with a mere $150,000 sticker price, not exactly top shelf), which I rented for a television documentary about rich people. It came with a $10,000 deductible, and the first time I drove it into a Bel-Air estate, the low-slung front end hit the apron of the driveway with a horrible grating sound that caused my soul to shrink. I proceeded up the driveway at five miles an hour, and everyone in sight turned away thinking, "Rental."

The bottom line: Without power, people tend to play it safe. Given power, even you and I would soon end up living large and acting like idiots. So pity the rich — and protect yourself. This is where Hilaire Belloc comes in.

He once wrote a poem about a Lord Finchley, who "tried to mend the Electric Light/Himself. It struck him dead: And serve him right!" Belloc wasn't tiresomely suggesting that the gentry all deserve a first-hand acquaintance with the third rail, as it were, but merely that they would be smart to depend on hired help. In social psychology terms, disinhibited Fast Forward types need ordinary cautious mortals to remind them that the traffic lights do in fact occasionally turn yellow or even, sometimes, red.

So, Eddie Griffin: next time you borrow a pal's car, borrow his driver, too. The world will be a safer place for the rest of us.

Richard Conniff is the author of The Natural History of the Rich.

Strange Sex

The Natural History Museum in London has a new exhibition called "Sexual Nature," and The Telegraph recently featured a few off the odd behaviors described there. Here is the prize for least seductive courtship technique:

Male porcupines also have a rather unpleasant habit. They spray the females with their urine in a bid to attract them. The urine is filled with hormones that cause the females to become sexually attracted.

And this might just be the most, oh, anti-climactic:

Red velvet mites try another ploy often seen in humans – they paint for their partners. The tiny male arachnids lay down intricate trails of silk for the female to follow.

If she likes the artistry of the trail, she will follow it to the end and sit on a deposit of sperm the male has left there.

You can read the whole article here.

March 2, 2011

Loud Neighbors

Howler monkey with a song in its heart

The first time I visited a rain forest, in Panama in about 1981, I woke up to a horrific roaring. My first thought was, "Oh, my God, Reagan's done it. He's fired off the cruise missiles."

Turned out it was just the howler monkeys saying "I'm awake now and if you come any closer I will throw shit at your head."

With that memory in mind, this item from The Mail caught my eye. It's about a few of our noisier neighbors:

The male blue whale's song reaches an astonishing 188 decibels, while a jet engine reaches 140. A staggering difference when you think that the decibel system means that a rise of ten decibels corresponds roughly to a doubling of volume.

That means a whale's song is almost five times louder than a jet.

Blue whale calls can be heard up to 1,000 miles away — which is useful because they can be miles apart from one another, and only occasionally meet to mate.

Their call is produced at a very low part of the frequency spectrum, at between 15 and 30 Hertz, because water is a good carrier of low-frequency noise.

By contrast, human voices are in the frequency range of 80 to 1100 Hertz. This means that we would feel a blue whale's song rumbling through our bones more than we would hear it.

Meanwhile, the loudest-mouthed land-based animal is one of our near relatives: the howler monkey.

These large New World monkeys live high in the upper canopies of jungles, ranging from southern Mexico down to northern Argentina.

The howler's screaming starts at 90 decibels and rises, and can be heard three miles away through dense tropical foliage. The high volume is achieved thanks to the unique anatomy of its throat.

Howlers have an outsized bone at the base of their tongue, which enables them to brace their tongue directly against their larynx and emit what sounds like a super-human scream.

It's an excruciatingly loud noise which is used by male and female alike to ward others off their territory.

Meanwhile, anyone who has sat out in the tropics at night will know the identity of the world's noisiest insect. Yes, it's the cicada — which produces sounds up to 120 decibels.

These creatures use their drum-like stomach organs to make a sound which can be heard 440 yards away.

The world's loudest cicada is the double drummer, from Australia, which has a six-inch wingspan and produces a noise that's been compared to the bagpipes.

Also found in Australia is the superb lyrebird, thought to have the loudest bird call in the world.

This colourful bird is only about the size of a chicken — but it's an outstanding mimic. It has even been heard imitating the sounds of chainsaws, trains and babies crying.

But if you really want to know how to make a racket, take note from the pistol shrimp.

By snapping its large claw together, this tiny shrimp is capable of making a noise at least as loud as a whale. Some estimates say that it can hit 200 decibels.

The pistol shrimp uses its vocal power to stun prey — chiefly small fish and other shrimps.

When the shrimp snaps its claw shut, a jet of water spurts out at a velocity of up to 62 mph.

This causes the pressure around the jet to drop, allowing a naturally occurring air bubble in the water, called a cavitation bubble, to swell.

The bubble generates huge acoustic pressures strong enough to kill small fish. The cracking sound is louder than a gunshot and has been known to interfere with ships' sonar navigation.

Pound for pound, the pistol shrimp may be the loudest animal in the world.

To put all this in perspective, the Mail article wraps up with an account of the loudest burp by a human female, 107 decibels at a beer festival (where else?) in Italy.

March 1, 2011

Reader Reactions to How Species Save Our Lives

Something that troubles me is that the emphasis seems to often be on the ways that human beings can benefit from our interaction with nature. Of course, the benefits from medicine and vaccines which have happened because of a discovery in nature are wonderful. But don't we have a moral and human obligation to protect all life, all species, whether or not we as a species benefits? We share this planet with other species. Those species, and individuals, have as much right to exist as we do.

Tim B

Others wrote to provide additional examples of benefits we have derived from nature:

Most interesting of recent note was a Bacteria discovered in Mono Lake in Eastern California that may be the key to treating Cyanide laced waters created by gold mining as it's physiology is uniquely adapted to that environment. Mono Lake is the oldest lake in North America and LA was quickly destroying it by taking all of it's feeding water to use for unchecked development. This incredibly unique species that is shocking scientists with hitherto thought impossible differences in it's metabolism could have been lost within the last few decades as Mono Lake was worthless and would be completely dry by now if not for the intervention of Environmentalists and the Naturalists with the keen eye to notice it.

John Duttle

Having worked in pharmaceutical research for many years, I often worry when articles proclaim that half of our medicinal drugs come from nature. I was therefore pleased that the author carefully explained that ACE inhibitors, which effectively reduce blood pressure, did not come from snake venom, but rather were developed based on our understanding of how the snake venom worked. In fact, most drugs do not come directly from nature; even the famous discovery of penicillin was not useful in human medicine until the natural substance was subjected to significant modification. This does not however detract from the key point of the article, but rather it enhances it. That is: it is not only important for us to protect what exists in our natural world, it is equally important for us to study the natural world and to understand in detail how it works.

W.A. Spitzer, Faywood, NM

This reader seemed to feel I had neglected a distinctively Filipino contribution to medical discoveries from nature. And in fact I did in this article but I have actually written about cone shells and Dr. Olivera at length in Smithsonian Magazine. Happy to see him get more attention here, as he surely deserves it:

Having communed with freshwater invertebrates (rotifers, cladocerans, and copepods) for half of my academic career, may I be allowed to share the excitement of colleagues, especially at the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines (UP-MSI), who have tapped familiar invertebrates for life-saving compounds? This time the role of 'traditional naturalists' who would march into hell (rain forests) for a heavenly cause (wonder drugs) seems to have been taken over by marine biologists (yes, men and women in white lab coats, with beakers and state-of-the-art gadgets). US-based Dr. Baldomero Olivera Jr. and our very own Dr. Lourdes Cruz have been trailblazers and models par excellence. Currently a motley group (marine biologists, biochemists, microbiologists, molecular biologists) has formed the cleverly and aptly named PHARMASEAS project to search for various drugs from invertebrates: sponges and snails (for now, cone shells and turrid snails). As fellow researchers love to say, they―the UP-MSI researchers―have their work cut out for them. And why not? The Philippines is said to be the 'center of the center of marine biodiversity'. It is one vast pharmacopoeia of more than 7000 islands, where just about any place, yes any place, in the country is touted to be no more than 6 hours away by car from the seashore.

This reader makes the very valid point that sanitation contributes more to human health than all the pharmaceuticals put together, and it's a good point. According to research by historian Philip Curtin, military deaths dropped dramatically in mid-nineteenth century because of sanitary improvements, and that was well before the conquest of diseases like yellow fever and malaria. I'd quibble a bit, and say that sanitation also ultimately depends on people who can recognize species like Vibirio cholerae, the bacterium that causes cholera. And solving the mystery of cholera was exactly the kind of heroic story I like to tell–only in this case it got told by writer Steven Johnson in his excellent book The Ghost Map:

And now a comment unrelated to the above rebuttal. I would like to point out that "industrial scale water treatment" (that is of making "fresh water" potable-disease free, as well as removing pathogens from

"used" water – sewerage) has had a much greater impact on the health of the now predominantly urban world population than "immunization and anti-biotics." But it doesn't make such good "heroic serendipitous stories" thus its relevance is under appreciated. The processes are what "nature" does but in a smaller area!

ecstatist

Finally, readers had some useful additions to my list of things we can do to slow the loss of species:

That said, the suggestion I would nominate for your list is this: Plant restored native plant habitat in your garden or around public buildings which use species that existed locally for millenia. These native species have co-evolved with native wildlife and are uniquely adapted to your local climate, without the need for extra water or fertilizing once established. You may have to modify your species selection and garden design to accommodate human needs, such as by not planting potentially flammable species near houses in fire-prone regions of the West; or not planting trees over or near septic tanks. But the more native species you plant, the more you can recreate and maintain important habitat for native wildlife.

Note that WILD plants are not necessarily NATIVE plants. Many species that grow wild were accidentally or deliberately introduced by humans from other parts of the world. You can get help on species identification, selection, cultivation tips, and nursery sources for often hard-to-find native plant species by contacting a native plant society in your area. Non-profit native plant promoting organizations exist for most states or regions in the country. Here's a link to a list of them compiled by the New England Wild Flower Society: http://www.newfs.org… Lee Kingman

Human Population 2011 – 7,000,000,000

Human Population 1999 – 6,000,000,000

Human Population 1959 – 3,000,000,000

Human Population 1875 – 1,500,000,000This is the problem, about which we are and have been in complete denial.

Sue Ferreira

1) Refuse to burn biofuels made from food crops (soy, canola, palm biodiesel, corn ethanol). They use cropland that displaces food, which creates an incentive to create more cropland out of existing ecosystems. To put this into perspective, America devoted over 30 thousand square miles of prime farmland to corn ethanol last year. Good luck not using corn ethanol, since its use is government mandated.2) Don't eat ocean fish …period. The seafood cards are largely ineffective. Eat farm-raised catfish and tilapia and shell fish instead. Google "Biodiversivist: An Exercise in Futility?"

3) Don't build your dream vacation cabin–rent one. They are a fantasy that degrade ecosystems and always end up, like a boat, being a hole that you pour money in.

4) Buy and preserve five to ten acres of ecosystem somewhere that is adjacent to more preserved ecosystems and put it into a conservation reserve program.

5) Animal products, meat, eggs, dairy, all use roughly the same amount of resources to produce. Use them all sparingly with your meals instead of making them the meals.

6) Support Planned Parenthood.

Biodiversivist, Russ Finley

Great summary of some of the medical highlights naturalists have contributed. One minor point I would argue with is your dictum, "Plant trees, and since maintaining them is the hard part, stick around to be a tree steward." Healthy forests are indeed quite a good thing for some species, but other species require other habitats — grasslands, wetlands, deserts, oceanic continental shelves, and on and on. Preserving habitats is the key thing; if you're in a place that naturally has forests, by all means plant trees, but in many places habitat conservation is better accomplished in other ways.

David M.

Thanks to all.

February 28, 2011

How Species Save Our Lives

Bothrops jacara (Photo by Daniel Loebmann)

Here's the latest (and last) column in my Specimens series for The New York Times:

When adding up the benefits from three centuries of species discoveries, I'm tempted to start, and also stop, with Sir Hans Sloane. A London physician and naturalist in the 18th century, he collected everything from insects to elephant tusks. And like a lot of naturalists, he was ridiculed for it, notably by his friend Horace Walpole, who scoffed at Sloane's fondness for "sharks with one ear, and spiders as big as geese!" Sloane's collections would in time give rise to the British Museum, the British Library, and the Natural History Museum, London. Not a bad legacy for one lifetime. But it pales beside the result of a collecting trip to Jamaica, on which Sloane also invented milk chocolate.

We still scoff at naturalists today. We also tend to forget how much we benefit from their work. Since this is the final column in this series about how the discovery of species has changed our lives, let me put it as plainly as possible: Were it not for the work of naturalists, you and I would probably be dead. Or if alive, we would be far likelier to be crippled, in pain, or otherwise incapacitated.

Large swaths of what we now regard as basic medical knowledge came originally from naturalists. John Hunter, for instance, was a colorful London physician, a generation or two after Sloane, and his passion for animals made him a model for Dr. Dolittle. (He may also have been the original Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde for his nighttime work sneaking cadavers in by the back door.) While others were only dimly beginning to contemplate the connection between humans and other animals, he made detailed flesh-and-blood comparisons, discovering, among other things, how bones grow and what course the olfactory nerves travel.

John Hunter (from a portrait by Joshua Reynolds)

Hunter, now regarded as the father of modern surgery, came out of a Scottish tradition that treated the study of nature as essential for developing a doctor's observational skills, and he drilled this attitude into his students. Among them was Edward Jenner, a country doctor who spent 15 years studying cuckoos (perhaps one reason he later got labeled a quack). But this research, combined "with Hunter's insistence on finely honed observation and cogent presentation, helped prepare Jenner's mind for his great work," according to science historian Lloyd Allan Wells. That work was the development of the world's first vaccine, for smallpox. Establishment physicians balked. But Jenner's bold idea would lead in time to vaccines against countless other deadly diseases, from yellow fever to polio. He thus gets credit (with a faint nod to the cuckoo) for saving more lives than anyone in the history of medicine.

You may perhaps be thinking that chocolate milk, Dr. Dolittle, and cuckoos make a very curious case for the importance of species. But our debt to the naturalists also takes more conventional form: Roughly half our medicines come directly from the natural world, or get manufactured synthetically based on discoveries from nature. The list includes aspirin (originally from the willow tree), almost all our antibiotics (from fungi that evolved in nature, not a Petri dish), and many of our most effective cancer treatments. I can remember a pale girl in second grade going off to die of lymphoma or leukemia; children with those diseases almost always died then. Now they routinely live, because of drugs developed from the Madagascar rosy periwinkle, a flowering plant. Many patients with lung, breast, uterine, and other cancers also now recover because in 1962 a botanist named Arthur S. Barclay collected samples of the Pacific yew tree, leading to the development of the anticancer drug Taxol. For those who think natural resources should stand or fall based on their current cash value, yew trees would have been basically worthless in 1961. But today, according to industry analysts IMS Health, Taxol is a $1.7 billion-a-year product.

Beyond giving us powerful new drugs, discoveries from the natural world also frequently open our eyes to the unsuspected workings of our own bodies. One of the more obvious effects of being bitten by the South American pit viper, Bothrops jacara, says the Harvard pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, is that "your blood pressure drops to the floor, and then you drop to the floor." So kill all the vipers, right? On the contrary, says Bernstein, a co-author of the 2008 book "Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity." The study of a key enzyme from this snake's venom revealed a new mechanism for controlling human blood pressure. ACE inhibitors, the direct result, are now our most effective remedy for hypertension and congestive heart failure, and certainly save more lives than these snakes ever killed.

Likewise, rapamycin, also known as Sirolimus, developed from a soil fungus on Easter Island, suppresses immune response through a pathway previously unknown to medicine. It's now widely used for organ transplants and as a coating on heart stents. By itself, that might not make anyone run around with an "I ♥ Fungi" bumper sticker. But consider this: A 2009 paper in Nature reported that mice dosed with rapamycin experienced a 28 to 38 percent increase in subsequent lifespan—and these mice were 60 years old (or the mouse equivalent) to start with. So Baby Boomers, are we starting to feel the fungal love?

Given the untapped potential of the natural world, you might think governments and drug companies would be racing to save species and screen them for other such extraordinary powers. In fact, says James S. Miller, vice president for science at the New York Botanical Garden, "only a tiny percentage of the world's plants have been screened," and even those "have only been screened against a small fraction of the diseases for which they could be effective." Instead, pharmacologically-active compounds developed over millions of years and found effective in the world's harshest laboratory—nature—routinely vanish, as the species in which they evolved go extinct.

Malaria deaths in 1870

There's one final way we owe our lives to naturalists. The absence of epidemic disease is now so completely taken for granted that it's hard to imagine we ever lived otherwise. But malaria once routinely killed people from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes. Yellow fever epidemics swept down like the wrath of God on cities as far north as Boston. In the nation's worst outbreak, in 1878, one in eight residents of New Orleans died, and everything south of Louisville, Ky., was "desolation and woe." All that changed in the miraculous 1890s, when researchers suddenly identified the causes of yellow fever, typhus, plague, dysentery and, above all, malaria. In each case, the solution depended on having precise knowledge—both taxonomic and behavioral — of the species involved, from microbial organisms to mosquitoes. As Patrick Manson, the father of tropical medicine (and a great Scottish naturalist), once put it, the study of the origins and causes of disease "is but a branch of natural history."

It's worth remembering all this now because some scientists say we are on the brink of a new era of epidemic diseases, with H.I.V., SARS, H1N1, and Ebola merely the ominous harbingers. New diseases are emerging because logging roads are reaching into the remotest habitats. Some scientists also think that deforestation is stripping away our biological buffer — the natural community of animals and plants that would normally dilute the effect of a disease organism and prevent it from spilling over to humans.

It's hard to accept that you and I may be vulnerable. Our brief century of freedom from disease has given us the delusion that we are separate from nature, somehow hovering above the world in which we live. So we no longer think it worthwhile to spend our money studying the species around us (better to search for life in outer space). And we accept the loss of forests and wetlands, not thinking that it may translate in time to the loss of our own families and friends. When the new wave of emerging diseases comes washing up on our doorsteps, we may find ourselves asking two questions: Where are the naturalists to help us sort out the causes and cures? And where are the species that might once have saved us?

But why wait? Why not ask those questions now?

POSTSCRIPT: The natural world ought to be a source of pleasure and consolation. So I've avoided pushing the conservation message too hard in this series. But I also hope readers are wondering what they can do in their own lives to slow the loss of species. Fortunately, a lot of the changes we can make to help the environment also help with our own economic struggles. Here's a baker's dozen of ideas. I invite readers to add their suggestions:

1. Reduce meat in your diet and stick to sustainable fisheries. (Find a pocket guide for your region.)

2. Buy less stuff, or buy it used.

3. Favor companies and countries that value the environment. (But beware of greenwashing. BP used to tout itself as environmentally aware.) Check the green rankings of top companies.

4. Add up your annual energy consumption (including air travel, gasoline, electricity, and heating fuel) and set a program to cut back by five percent a year. Be clever and you may hardly notice. Start by making a one degree change in the thermostat, and replacing incandescent light bulbs with compact fluorescent lights. (Some energy audit programs will do it for you and you will spend less for the service than you will save in utility costs in the first year alone.)

5. Walk, bike, or take public transportation. The exercise will do you good (and you might see an interesting bird or bug on route).

6. Get acquainted with some of our weird, delightful fellow species. Any book by Gerald Durrell, for instance, "My Family and Other Animals," is a fine place to start,

7. Learn to identify 10 species of plants and animals in your own neighborhood, then 20, and onward.

8. Stop using lawn pesticides and fertilizers. They contaminate nearby waterways. For the same reason, don't dump old prescriptions down the toilet.

9. Reduce water use, particularly for lawns; it depletes a limited resource, sometimes directly damaging habitat.

10. Plant trees, and since maintaining them is the hard part, stick around to be a tree steward.

11. Lobby public officials to do smart things like installing more sidewalks, limiting carbon emissions,

and investing in conservation of threatened species.

12. Adopt a species that needs help and actively support its conservation. Groups exist focused on tigers, rhinos, chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, frogs, and so on.

13. Encourage your local zoo to focus on species conservation.

Many thanks to the readers of Specimens. The entire eight-part series can be read here.

February 24, 2011

BBC Wildlife on The Species Seekers: "Brilliant, 5 Stars"

BBC Wildlife on The Species Seekers: "Brilliant, Invaluable"

February 23, 2011

The Luddite Revolution: Birth of a Brand

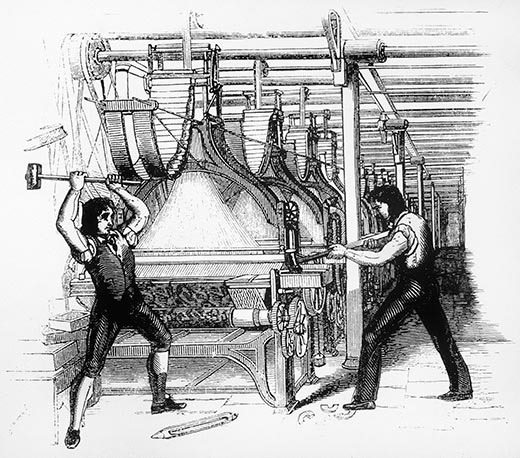

An early Luddite protester

This is a piece I wrote for the March issue of Smithsonian magazine:

In an essay in 1984—at the dawn of the personal computer era—the novelist Thomas Pynchon wondered if it was "O.K. to be a Luddite," meaning someone who opposes technological progress. A better question today is whether it's even possible. Technology is everywhere, and a recent headline at an Internet humor site perfectly captured how difficult it is to resist: "Luddite invents machine to destroy technology quicker."

Like all good satire, the mock headline comes perilously close to the truth. Modern Luddites do indeed invent "machines"—in the form of computer viruses, cyberworms and other malware—to disrupt the technologies that trouble them. (Recent targets of suspected sabotage include the London Stock Exchange and a nuclear power plant in Iran.) Even off-the-grid extremists find technology irresistible. The Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, attacked what he called the "industrial-technological system" with increasingly sophisticated mail bombs. Likewise, the cave-dwelling terrorist sometimes derided as "Osama bin Luddite" hijacked aviation technology to bring down skyscrapers.

For the rest of us, our uneasy protests against technology almost inevitably take technological form. We worry about whether violent computer games are warping our children, then decry them by tweet, text or Facebook post. We try to simplify our lives by shopping at the local farmers market—then haul our organic arugula home in a Prius. College students take out their earbuds to discuss how technology dominates their lives. But when a class ends, Loyola University of Chicago professor Steven E. Jones notes, their cellphones all come to life, screens glowing in front of their faces, "and they migrate across the lawns like giant schools of cyborg jellyfish."

That's when he turns on his phone, too.

The word "Luddite," handed down from a British industrial protest that began 200 years ago this month, turns up in our daily language in ways that suggest we're confused not just about technology, but also about who the original Luddites were and what being a modern one actually means.

Blogger Amanda Cobra, for instance, worries about being "a drinking Luddite" because she hasn't yet mastered "infused" drinks. (Sorry, Amanda, real Luddites were clueless when it came to steeping vanilla beans in vodka. They drank—and sang about—"good ale that's brown.") And on Twitter, Wolfwhistle Amy thinks she's a Luddite because she "cannot deal with heel heights" given in centimeters instead of inches. (Hmm. Some of the original Luddites were cross-dressers—more about that later—so maybe they would empathize.) People use the word now even to describe someone who is merely clumsy or forgetful about technology. (A British woman locked outside her house tweets her husband: "You stupid Luddite, turn on your bloody phone, i can't get in!")

The word "Luddite" is simultaneously a declaration of ineptitude and a badge of honor. So you can hurl Luddite curses at your cellphone or your spouse, but you can also sip a wine named Luddite (which has its own Web site: www.luddite.co.za). You can buy a guitar named the Super Luddite, which is electric and costs $7,400. Meanwhile, back at Twitter, SupermanHotMale Tim is understandably puzzled; he grunts to ninatypewriter, "What is Luddite?"

Almost certainly not what you think, Tim.

Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it. Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry. Nor was the technology they attacked particularly new. Moreover, the idea of smashing machines as a form of industrial protest did not begin or end with them. In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say they were good at branding.

The Luddite disturbances started in circumstances at least superficially similar to our own. British working families at the start of the 19th century were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment. A seemingly endless war against Napoleon's France had brought "the hard pinch of poverty," wrote Yorkshire historian Frank Peel, to homes "where it had hitherto been a stranger." Food was scarce and rapidly becoming more costly. Then, on March 11, 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing center, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

That night, angry workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swath of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north. Fearing a national movement, the government soon positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories. Parliament passed a measure to make machine-breaking a capital offense.

But the Luddites were neither as organized nor as dangerous as authorities believed. They set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered. In one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester. The owner ordered his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18. Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day.

Earlier that month, a crowd of about 150 protesters had exchanged gunfire with the defenders of a mill in Yorkshire, and two Luddites died. Soon, Luddites there retaliated by killing a mill owner, who in the thick of the protests had supposedly boasted that he would ride up to his britches in Luddite blood. Three Luddites were hanged for the murder; other courts, often under political pressure, sent many more to the gallows or to exile in Australia before the last such disturbance, in 1816.

Smashing textile machinery

One technology the Luddites commonly attacked was the stocking frame, a knitting machine first developed more than 200 years earlier by an Englishman named William Lee. Right from the start, concern that it would displace traditional hand-knitters had led Queen Elizabeth I to deny Lee a patent. Lee's invention, with gradual improvements, helped the textile industry grow—and created many new jobs. But labor disputes caused sporadic outbreaks of violent resistance. Episodes of machine-breaking occurred in Britain from the 1760s onward, and in France during the 1789 revolution.

As the Industrial Revolution began, workers naturally worried about being displaced by increasingly efficient machines. But the Luddites themselves "were totally fine with machines," says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites. They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called "a fraudulent and deceitful manner" to get around standard labor practices. "They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods," says Binfield, "and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns."

So if the Luddites weren't attacking the technological foundations of industry, what made them so frightening to manufacturers? And what makes them so memorable even now? Credit on both counts goes largely to a phantom.

Ned Ludd, also known as Captain, General or even King Ludd, first turned up as part of a Nottingham protest in November 1811, and was soon on the move from one industrial center to the next. This elusive leader clearly inspired the protesters. And his apparent command of unseen armies, drilling by night, also spooked the forces of law and order. Government agents made finding him a consuming goal. In one case, a militiaman reported spotting the dreaded general with "a pike in his hand, like a serjeant's halbert," and a face that was a ghostly unnatural white.

In fact, no such person existed. Ludd was a fiction concocted from an incident that supposedly had taken place 22 years earlier in the city of Leicester. According to the story, a young apprentice named Ludd or Ludham was working at a stocking frame when a superior admonished him for knitting too loosely. Ordered to "square his needles," the enraged apprentice instead grabbed a hammer and flattened the entire mechanism. The story eventually made its way to Nottingham, where protesters turned Ned Ludd into their symbolic leader.

The Luddites, as they soon became known, were dead serious about their protests. But they were also making fun, dispatching officious-sounding letters that began, "Whereas by the Charter"…and ended "Ned Lud's Office, Sherwood Forest." Invoking the sly banditry of Nottinghamshire's own Robin Hood suited their sense of social justice. The taunting, world-turned-upside-down character of their protests also led them to march in women's clothes as "General Ludd's wives."

They did not invent a machine to destroy technology, but they knew how to use one. In Yorkshire, they attacked frames with massive sledgehammers they called "Great Enoch," after a local blacksmith who had manufactured both the hammers and many of the machines they intended to destroy. "Enoch made them," they declared, "Enoch shall break them."

This knack for expressing anger with style and even swagger gave their cause a personality. Luddism stuck in the collective memory because it seemed larger than life. And their timing was right, coming at the start of what the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle later called "a mechanical age."

People of the time recognized all the astonishing new benefits the Industrial Revolution conferred, but they also worried, as Carlyle put it in 1829, that technology was causing a "mighty change" in their "modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand." Over time, worry about that kind of change led people to transform the original Luddites into the heroic defenders of a pre-technological way of life. "The indignation of nineteenth-century producers," the historian Edward Tenner has written, "has yielded to "the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers."

The original Luddites lived in an era of "reassuringly clear-cut targets—machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer," Loyola's Jones writes in his 2006 book Against Technology, making them easy to romanticize. By contrast, our technology is as nebulous as "the cloud," that Web-based limbo where our digital thoughts increasingly go to spend eternity. It's as liquid as the chemical contaminants our infants suck down with their mothers' milk and as ubiquitous as the genetically modified crops in our gas tanks and on our dinner plates. Technology is everywhere, knows all our thoughts and, in the words of the technology utopian Kevin Kelly, is even "a divine phenomenon that is a reflection of God." Who are we to resist?

The original Luddites would answer that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it's possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It's about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don't want to become, as Carlyle warned, "mechanical in head and in heart," it may help, every now and then, to ask which of our modern machines General and Eliza Ludd would choose to break. And which they would use to break them.

February 22, 2011

The Best Rx: Facing Up to Mistakes

A study from Johns Hopkins reveals that the father of successful neurosurgery, Harvey Cushing, a driven, egotistical figure, was nonetheless also routinely frank about admitting his mistakes. I profiled Cushing recently (see below) and was also struck that, apart from being meticulously careful in his work, he also relied on methodical record-keeping and self-criticism to improve his results. In the new study, medical student Katherine Latimer and her co-authors

A study from Johns Hopkins reveals that the father of successful neurosurgery, Harvey Cushing, a driven, egotistical figure, was nonetheless also routinely frank about admitting his mistakes. I profiled Cushing recently (see below) and was also struck that, apart from being meticulously careful in his work, he also relied on methodical record-keeping and self-criticism to improve his results. In the new study, medical student Katherine Latimer and her co-authors

… were surprised by Cushing's frank and copious documentation of his own shortcomings. His notes acknowledged mistakes that may have resulted in patients' deaths, as well as those that didn't seem to harm patients' outcomes. They said the documentation took place in an era in which malpractice litigation was becoming a growing concern for doctors. Though malpractice penalties were substantially smaller in Cushing's day, lawsuits presented a serious risk for physicians' reputations, the authors noted.

The authors also emphasized that Cushing practiced in a time of enormous surgical innovation. For example, patient mortality from surgical treatment of brain tumors fell from 50 percent to 13 percent during his career. While some of this jump ahead was due to improving technology, the authors propose that part of the reason was open documentation of errors, which helped Cushing and other surgeons develop fixes to avoid them.