Richard Conniff's Blog, page 112

January 23, 2011

Heroic Naturalists or Imperialist Dogs?

Here's the latest column in my Specimens series for the New York Times.

What does it mean to discover a species? Who should get the credit for it? Why did early naturalists think it worth risking their lives, and often losing them, to ship home the first specimens of a previously unknown butterfly or bat? These turn out to be tangled questions, and it is easy to get stuck on the thorns.

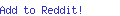

Not long ago, for instance, I wrote that a 19th-century French missionary and naturalist in China, Pére Armand David, had "discovered" the snub-nosed golden monkey. A reader sent me this somewhat testy comment: "The answer to the question 'who discovered it' is actually the Chinese." Père David had merely "observed it and introduced it (and many other animals) to the West and into the Western zoological system."

My irritated reader had a point, of a misguided sort. It's common these days to dismiss the scientific classification and naming of "new" species as just one more Western appropriation of other peoples' natural resources, and the golden monkey can seem like a particularly egregious instance. Europeans first saw the species in the form of images in Chinese paintings and porcelains. But it looked so odd, with a fringe of flame red hair around its bluish-white face, that they mistook it for a figment of the Chinese imagination.

My irritated reader had a point, of a misguided sort. It's common these days to dismiss the scientific classification and naming of "new" species as just one more Western appropriation of other peoples' natural resources, and the golden monkey can seem like a particularly egregious instance. Europeans first saw the species in the form of images in Chinese paintings and porcelains. But it looked so odd, with a fringe of flame red hair around its bluish-white face, that they mistook it for a figment of the Chinese imagination.

David himself may never actually have seen these mountain-dwelling monkeys in the wild. Instead, his Chinese hunters brought him six specimens in the course of a long and productive expedition into western Sichuan province. David shipped the specimens back to Paris, along with more than 100 other mammal species. There, in an act of blithe cultural hodgepodgery, a French naturalist described the golden monkey in a scientific journal and gave it the species name roxellana to commemorate the Ukrainian wife of an Ottoman Turkish sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, because monkey and wife both had distinctive up-turned noses. You can see how this might leave people in China feeling a little left out.

Nor were they alone. The truth is that many of the species discovered by early naturalists had already been known to local people, sometimes in great detail, long before outsiders arrived to describe them scientifically. Moreover, the naturalists often depended on knowledgeable locals to show them what was there, and seldom gave proper credit for the help. But to call this local knowledge "discovery" is like saying Newton didn't discover gravity, because people already knew that things have a way of falling down.

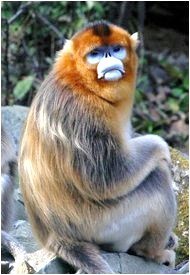

Naturalists often relied on local collectors

The key to scientific discovery is making knowledge available to people everywhere, usually by publishing a detailed description in a scientific journal. It means saying exactly how the proposed species resembles other related species, and how it's different, thereby assigning it to a place in a universal system of classification. (Even highly-trained scientists can sometimes gawp at a species for a century or two before they notice the differences. Thus scientists have only lately confirmed that the African elephant is actually two distinct species, the savanna elephant and the forest elephant. Technically speaking, the latter species was only discovered in 2010.)

Discovery also means giving your find a name, by genus and species. The Latinate construction of these names can sometimes sound as if they are meant to exclude rather than inform. (The soldier fly Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides comes stumbling to mind). But before this system of species names came into existence, people could hardly communicate about the plants and animals in their own backyards — one town's "dandelion" was another's "pissabed" — much less from one country to another. After, they could start to see and talk about connections among species at opposite ends of the Earth.

The Chinese meanwhile had abundant local knowledge of their plants and animals, and Western explorers gladly took advantage of it, according to Fa-Ti Fan, a historian at Binghamton University and author of "British Naturalists in Qing China." But, Fan writes, the Chinese "did not have a discipline, a system of knowledge, or even a coherent scholarly tradition equivalent to Western notions of 'natural history,' 'botany,' or 'zoology.' "

David Armand in priestly attire

And in disguise. (Both by Clare Conniff)

And in that context, Pére Armand David's discoveries — unencumbered by asterisks or quotation marks — were crucial. He certainly displayed plenty of colonial arrogance, flouting local lords and their rules. (He had come to China "pursued with the thought of dying while working at the saving of infidels," and there was a certain unholy insouciance about the way he drew his gun on would-be bandits.) But long before the Chinese themselves noticed, he warned that the plundering of their forests would wipe out "hundreds of thousands of animals and plants given to us by God," leaving behind a landscape of horses, pigs, wheat and potatoes. If David had not brought them to the attention of the outside world, many of his new species — among them the giant panda — would in fact now be lost.

One of his least heroic discoveries, now known as Père David's deer, or Elaphurus davidianus, was described on the basis of skins he probably obtained illegally, from the imperial hunting grounds south of Beijing. That find led European diplomats to press for live specimens to be shipped back to Europe for breeding. When Chinese soldiers bivouacking on the imperial hunting grounds later shot and ate the last remaining deer there, the species was extinct in China. But because of reintroductions from Europe — and the work of Pére David — these deer in fact now number about a thousand in their native habitat.

Discoveries by another early naturalist in China, Patrick "Mosquito" Manson, later enabled the government there to wipe out the hideously debilitating disease called elephantiasis. His work also led to the eradication or control of malaria in countries around the world. Likewise, work by early discoverers recently enabled researchers in China to pin down the source of SARS to four species of horseshoe bat in the genus Rhinolophus.

A simple-minded story line about imperialists appropriating natural resources — with great white hunters playing out their heroic exploits at the expense of local cultures — may have its revisionist appeal. But it's at least equally important to recognize that the work of early naturalists continues to save lives and protect resources today. The best evidence of its value is that every country from China to Gabon to Colombia now employs this scientific system of discovery and classification as a better way to understand not just our world, but theirs.

Postscript: Thank you to the many readers who sent me names, in response to last week's column, of naturalists who died in the course of discovery. The several dozen additions to The Wall of the Dead include an Italian prince who was trampled to death by an enraged elephant (but discovered one of Africa's most spectacularly colorful birds), an Indian pollen researcher killed by terrorists while reportedly trying to help a child during the 1986 hijacking of a Pan Am flight in Karachi and a Brazilian naturalist who survived a series of debilitating tropical diseases before finally being fatally poisoned by contact with a frog. They had in common the belief that understanding the natural world was important enough to wager their lives on it.

January 21, 2011

Why Species Matter–Or Putting a Value on a Vulture

This is a piece I published a while back at Yale Environment 360

We live in what is paradoxically a great age of discovery and also of mass extinction. Astonishing new species turn up daily, as new roads and new technologies penetrate formerly remote habitats. And species also vanish forever, at what scientists estimate to be 100 to 1,000 times the normal rate of extinction.

Over the past few years, as I was working on a book about the history of species discovery, I often found myself coming back to a fundamental question: Why do species matter? That is, why should ordinary people care if scientists discover one species or pronounce the demise of another?

It may seem too obvious to need asking. In certain limited contexts, people clearly do care. We will go to great lengths to protect a boutique species like the giant panda, for instance. We also thrill to the possibility of finding the slightest microbial hint of life in outer space, hardly blinking when the U.S. government spends $7 billion a year largely for that purpose. Meanwhile, we spend pennies exploring the alien life forms that are all around us here on Earth.

Maybe it's just human nature not to value — or even see — the thing that's right in front of our faces. And maybe it's also a failure of communication.

That is, scientists may need to explain their work on a far more basic level — not "Why do species matter?" but "Is food important to you?" or "Do you want your children to have effective medicines when they get sick?" or even "Do you like to breathe?"[image error] None of these questions overstates the importance of species.

For instance, Prochlorococcus is an ocean-dwelling genus of cyanobacteria and among the most abundant life forms on Earth. Why should we care? Because it produces about 20 percent of the oxygen we breathe — and yet until an MIT microbiologist named Sally Chisholm discovered it in 1986, Prochlorococcus was unknown. We need to understand in short that our lives depend on species most of us have never heard of — species we otherwise tend to shrug off as obscure, trivial, even undesirable.

Vultures, for instance. When we cause a species to go into decline, we almost never know — and hardly even stop to think about — what we might be losing in the process. In truth, it may be hard to think about, because the cascading effects of our actions are sometimes freakishly distant from the original cause. So in India in the early 1990s, farmers began using the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac for the apparently worthy purpose of relieving pain and fever in their livestock. Unfortunately, vultures scavenging on livestock carcasses accumulated large quantities of the drug and promptly died of renal failure. Over a 14-year period, populations of three vulture species plummeted by between 96.8 and 99.9 percent.

Losing these efficient scavengers meant livestock carcasses often got left in the open to rot. It was one of those "ecosystem services" — manufacturing oxygen, soaking up carbon dioxide, preventing floods, taking out the garbage — that species generally provide unnoticed, until they stop. But the impacts went well beyond the stench, according to a 2008 article in Ecological Economics. Moving into the niche vacated by the vultures, feral dog populations boomed by up to 9 million animals over the same period. Dog bites and the incidence of rabies in humans also increased, and the authors conservatively estimated that an additional 48,000 people died during the 14-year period as a result. Calculating the bottom-line worth of what we get from the natural world is notoriously difficult. But even pricing lives at a fraction of developed world values, the near-total loss of three insignificant vulture species has so far cost India an estimated $24 billion.

A diversity of species can also help prevent the emergence of new diseases, though we tend to blame, rather than credit, nature for this particular ecosystem service. We sometimes respond to Lyme disease, for instance, by trying to kill the major players, blacklegged ticks and white-footed mice. But the "dilution effect," proposed by Rick Ostfeld at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, suggests counterintuitively that having the broadest variety of host species in a habitat is a better way to limit disease. Some of those hosts will be ineffective, or even dead ends, at transmitting the infectious organism. So they dilute the effect and keep the disease organism from building up and spilling over to humans. But when we reduce biodiversity by breaking up the forest for our backyards, we accidentally favor the most effective host — in this case, the white-footed mouse. And we free the undiluted disease organism to operate at full strength.

The implications go well beyond Lyme disease. Around the world over the past half-century, researchers have tracked about 150 emerging infectious diseases, from Ebola to HIV, with 60 to 70 percent being zoonotic — that is, transmitted from animals to humans. "The question," says Aaron Bernstein, a Harvard pediatrician and co-editor of the 2008 book Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity, "is whether humans are doing something to make these zoonotic diseases come out of the woodwork." Clearly, we are doing a lot of one particular thing — knocking down forests and creating species-poor habitats with no "dilution effect" in their place. Thus the fear is that many more such epidemics may lie ahead.

And yet the value of even big, charismatic species remains so poorly understood that a Rutgers University philosopher writing in The New York Times recently proposed gradually wiping out cruel carnivorous species and replacing them with gentle vegetarians. He was upset that lions do not lie down with lambs, except to eat them for dinner. And he was apparently oblivious to the larger cruelty called a trophic cascade: Loss of predators strips a habitat of its diversity and leaves behind the animal equivalent of the civil service, or what writer David Quammen has called "a pestilence of minor nibblers."

For instance, in the rocky world between high and low tides on the Pacific Coast near Seattle, the food chain (or trophic community, from the Greek trophikos, or nourishment) consists of barnacles, limpets, chitins, anemones, and particularly mussels. Starfish are the dominant predator. So mussels normally crowd up along the high tide line, where starfish are less likely to chomp them. In one study, a biologist removed the starfish to see what would happen. The mussels soon crept down toward deeper water, crowding out other species. Within a few years, only eight of the 15 original species still lived in that neighborhood. For all their apparent cruelty, killer species can be a means of fostering biodiversity.

So do individual species matter? Or is it just the diversity of species? The truth is that our understanding of the natural world is far too primitive for anyone to say one species is important, and another isn't. In fact, scientists don't even have names for most species; they've described only about 1.8 million of them, with an estimated 10 to 50 million still to go. So instead of waging pitched battles for individual species, conservationists in recent years have prudently tended to emphasize diversity, working to protect large swaths of habitat for a multitude of species. It's the motorcycle mechanic's approach to conservation, as articulated by Aldo Leopold: "To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering."

But that should not stop us from trumpeting the benefits to humanity from individual species that might otherwise get written off as worthless, or even as impediments to human progress. Some conservationists may cringe at the thought of cheapening the natural world by defending it in economic terms. But NASA manages to hold onto a sense of wonder about its mission while simultaneously touting the idea that space exploration can pay for itself in technology transfers to the civilian world. (There's actually a NASA "spinoff coloring book." It celebrates an outer space mirror-polishing technology now also used to make ice skates go "super fast!") The difference is that the spinoff argument for exploring species here on Earth is far more persuasive.

The yew, for instance, was until recently a "trash tree," says David J. Newman of the National Cancer Institute; he figures it was last valued around the time his ancestors used it to fashion bows for firing arrows at the Battle of Agincourt. But it's now the source for taxol, relied on by tens of thousands of people as a life-saving treatment for breast, prostate, and ovarian cancers. Sales topped $1.6 billion last year. Likewise, no one ever marched to save the gila monsters, but their venom is the source of a new drug for people who resist conventional treatments for Type 2 diabetes, an epidemic disease now on track to affect more than a third of all Americans over their lifetimes.

In fact, the common idea that drug companies can cook up their medicines out of thin air through "rational drug design" in the laboratory is simply wrong. One recent study looked at more than 1,000 drugs approved worldwide over a 20-year period and found not one that was traceable to a totally synthetic source. Getting our ideas from species in the natural world is still the rule.

Likewise, wild species continue to be the mother lode of genetic material for making agricultural crops more productive, or more resistant to pests, disease, and drought. That kind of bio-prospecting is likely to become far more important over the next few years as biologists begin to explore the bacteria, fungi, and other microbial life forms that help plants do what they do. In fact, we will have little choice but to find smarter ways of exploiting the hidden resources of the natural world. If NASA in its glory years had a mission — to get to the moon in 10 years — biologists now have one, too: To sustain the species and habitat here on Earth that will be essential to providing food, medicine, and sanity as the human population grows to 9 billion people over the next 40 years.

There is one final argument for the value of species, and it has to do with beauty, biophilia, and a sense of the sacred. In the course of researching my book on species discovery, it seemed to me that one young 19th-century specialist in marine mollusks made the case most persuasively. In pursuit of new species along the coast of Alaska, naturalist William T. Dall experienced all the usual adventures, among them a long frigid trip in a sealskin dory across open water, trying to avoid being crushed by waves loaded with cakes of ice.

He gave his family an eloquent explanation of what motivated him, and by extrapolation most other species seekers: "There is a singular delight," he wrote home in 1866, "in taking these delicate and almost microscopic animals and putting them under a strong glass, seeing the tiny heart beat, and blood circulate and gills expand, counting the muscles and blood vessels and almost the tiny disks that form the blood and to know that you are the first that has penetrated these mysteries and are perhaps the only one who ever will, and that all your notes and drawings and observations are so much solid knowledge added to the power and grace and beauty of the Infinite."

January 19, 2011

In A Terrible Death, A Great Discovery

Eugenio Ruspoli

Readers have been sending in a steady stream of naturalists who lost their lives in the cause of discovery and I have been adding them to the Wall of the Dead. This one, suggested by reader Cagan Sekercioglu in Utah, caught my eye:

In the early 1890s, the Italian government sent out a mission to secure its colonial pretensions to an Ethiopian protectorate. Prince Eugenio Ruspoli, the son of the mayor of Rome and scion of a venerable noble family, seems to have played the multiple roles of emissary, leader of a conquering military force, explorer, and great white hunter.

He apparently wrote a book about his time in Ethiopia, In the land of Unexplored Africa and Mirra, published in Italian in 1892.

The following year, Ruspoli led an expedition to the Amara Mountains. In his 1897 book Through Unknown African Countries, the American explorer Arthur Donaldson Smith suggests that Ruspoli traveled with a large armed force and frequently waged war on local tribes. He also came to a violent end:

I now learned that Prince Ruspoli had got as far as the Amara, having followed up the river Jub far to the north of my line of march, and that he had been killed by an elephant near the foot of the Amara Mountains. The chief told me that Ruspoli had spent a long time in his village, and that after his death his body had been taken up the mountain again and buried alongside of the graves of some noted chiefs. One of the Amara told me that he was an eye-witness of the thrilling scene of Ruspoli's last hunt.

When he reached the Galana Amara with his caravan, death overtook him. In the open plain ahead of his line of march appeared a large elephant. Ruspoli, who was ahead, motioned to his caravan to stop, and walked out alone to have a try for the beast. He crept to within thirty yards, and fired. Suddenly the huge animal turned on him, and in the twinkling of an eye the Prince was suspended aloft in the grasp of that powerful trunk.

To the excited natives, powerless to interfere, it seemed an interminable time that the beast kept swinging Ruspoli about in the air before he lowered the body to the ground and stamped out the little life that was left.

Ruspoli's turaco

But in his baggage, Ruspoli had left behind a spectacular discovery, a specimen of the brightly colored bird that would later become known as Ruspoli's turaco (Tauraco ruspolii). It was named by T. Salvadori, who studied and wrote about Ruspoli's collection. You can find out more about the species here.

(A curious sidenote, you can now rent the Ruspoli family's villa outside Rome.)

January 18, 2011

The Lonely Traveler Finds A Companion

White-eyed parakeet, now Aratinga leucophthalma (Photo by Wagner Machado Carlos Lemes)

[image error]During his eleven years in the Amazon, the great explorer Henry Walter Bates often struggled with loneliness. This is a story about the joy of finding a companion in his travels:

On re-crossing the river to Aveyros in the evening, a pretty little parrot fell from a great height headlong into the water near the boat, having dropped from a flock which seemed to be fighting in the air. One of the Indians secured it for me, and I was surprised to find the bird uninjured. There had probably been a quarrel about mates, resulting in our little stranger being temporarily stunned by a blow on the head from the beak of a jealous comrade.

The species was the Conurus guianensis, called by the natives Maracana– the plumage green, with a patch of scarlet under the wings. I wished to keep the bird alive and tame it, but all our efforts to reconcile it to captivity were vain; it refused food, bit everyone who went near it, and damaged its plumage in its exertions to free itself.

My friends in Aveyros said that this kind of parrot never became domesticated. After trying nearly a week I was recommended to lend the intractable creature to an old Indian woman, living in the village, who was said to be a skillful bird-tamer. In two days she brought it back almost as tame as the familiar love-birds of our aviaries. I kept my little pet for upwards of two years; it learned to talk pretty well, and was considered quite a wonder as being a bird usually so difficult of domestication. I do not know what arts the old woman used– Captain Antonio said she fed it with her saliva. The chief reason why almost all animals become so wonderfully tame in the houses of the natives is, I believe, their being treated with uniform gentleness, and allowed to run at large about the rooms.

Our Maracana used to accompany us sometimes in our rambles, one of the lads carrying it on his head. One day, in the middle of a long forest road, it was missed, having clung probably to an overhanging bough and escaped into the thicket without the boy perceiving it. Three hours afterwards, on our return by the same path, a voice greeted using a colloquial tone as we passed–"Maracana!" We looked about for some time, but could not see anything, until the word was repeated with emphasis– "Maracana-a!" When we espied the little truant half concealed in the foliage of a tree, he came down and delivered himself up, evidently as much rejoiced at the meeting as we were.

The End of Exploration?

This response to my reminiscence about Ted Parker ( "Dying for Discovery") came in, and I think the message–about "a segment of the scientific community that is almost always out of sight until some tragedy occurs"–deserves attention. It's from field biologist Andrew Mack:

I was a dear friend of Ted's, we both began as birders at the Lancaster County Bird Club and I went out to the University of Arizona where for a while I was part of an incredible union of like souls— Ted Parker, Kenn Kaufmann, Doug Stotz, Steve Hilty, Mark Robbins, to name a few. As you know, many of us carry on with the same sort of work that Ted was doing when he died. Sadly, death brought him a lot more legitimacy than he carried in life. There were more than a few of our colleagues who scoffed at what he did (and still scoff at those of us trying to continue such explorations).

Mack makes a point I have also heard from other readers, that naturalists who survive their field work often come away maimed by it:

I've struggled with filariasis for over a decade, have had so many malarial fevers I lost count years ago and always have my quinine within reach; tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, dengue, typhoid, Ross River Fever, and the list goes on. Things like botflies and eye leeches are like splinters to a carpenter. I've had plane landings on grass strips that still make my sphincter tighten just thinking about them, and at least six pilots I've flown with in Papua New Guinea have died in crashes. It is a ticking clock we don't think about. The compulsion also shreds relationships (Ted had two divorces already when he died). I don't say this to brag in any way, but to point out that we, with this compulsion to explore, just deal with these things. Most of my friends have equally long and debilitating medical histories, many have had much worse. I count myself lucky.

Financial support for their work is also a perennial issue:

Most of us struggle on with minimal support, and that is part of the reason it is dangerous. We do this work on shoestrings. When a partner like BBC comes in, or you work with a mining exploration company (as I did with Freeport McMoran in Irian Jaya), you see what it could be like with a little financial backing. The world of donors simply does not value this kind of science.

I used to work for Conservation International's RAP program. Sure it is celebrating its 20th anniversary (I contributed to the commemorative volume Leeanne Alonso and Steve Richards put together), but RAP barely survives. CI does not adequately support RAP. I tried another major conservation organization for years but they too lost interest in exploratory field work. I then shifted to a famous natural history museum, but they too have little interest in expeditions or recent history in this sort of work. The priorities are set by donors and funding agencies. Expeditions and exploration are just about impossible to fund.

Having survived diseases that don't even have a name yet and lived for years in camps without power or connection to the outside world, I (and my like-spirited explorers) are now withering away for lack of funds.

It is great that 20 years later Ted and Al are getting some press. I believe Ted would be gratified by the conservation that is at least in part attributed to his work, plus the commemorative publications and species named in his honor. But I also believe, if he was alive now, he would be even more frustrated than he was in the 70's and 80's by the lack of interest within the professional and donor communities in his sort of work. RAP barely survives and the other conservation NGOs do even less. Few museums mount expeditions or seriously support exploration.

Straight natural history is considered "not real science" by many academics. The flurry of laments and calls for more natural history after the crash have long since quieted, and little changed. Those of us from Ted's era have soldiered on with less and less support. But we're getting old and there are not many young Ted's coming up behind us. When our knees finally give out after one mountain too many or our livers from one Plasmodium too many, we'll retire to our computers and work on the backlog.

Just as it was tragic that Ted and Al died so young and before their time, so too is it tragic that the age and spirit of exploration seems to be dying while there is still so much left to do. Thanks for your efforts to keep the spirit alive.

Sincerely,

Andy

Scaring or Scolding? Early Conservationists Tried Both

In the early 19th century, long before the rise of the conservation movement, one or two naturalists were already seeing that humans could drive down populations of certain species. And they mounted conservation efforts to protect them.

In the autumn of 1807, for instance, the residents of Philadelphia were slaughtering and eating robins in such vast numbers that ornithologist Alexander Wilson resorted to conservation by false rumor. He planted a story in local newspapers advising cautious readers that the pokeberries the birds were then gorging on made their flesh unwholesome, and he was "righteously elated," according to one historian, when his story knocked the bottom out of the robin market.

Another Philadelphia man, the entomologist Thomas Say, traveled to the Rocky Mountains in 1819 and 1820. On route, he was plainly disgusted by whitenewcomers to the West: "It is common for hunters to attack large herds of [bison], and having slaughtered as many as they are able, from mere wantonness and love of this barbarous sport, to leave the carcasses to be devoured by the wolves and birds of prey; thousands are slaughtered yearly, of which no part is saved except the tongues. This inconsiderate and cruel practice, is undoubtedly the principal reason why the bison flies so far and so soon from the neighbourhood of our frontier settlements."

This was 30 years before the first vague stirrings of the American conservation movement. Naturalists elsewhere were still earnestly praying for the wilderness to be tamed and Christianized. But Say was already advocating "some law for the preservation of game … rigidly enforced" to prevent "the wanton destruction of these valuable animals, by the white hunters."

January 16, 2011

Dying for Discovery

Members of the Dutch Commission on route to New Guinea

The second column in my "Specimens" series, based on my book The Species Seekers, appears today in the New York Times

Almost 20 years ago now, in western Ecuador, I traveled with a team of extraordinary biologists studying a remnant of forest as it was being hacked down around us. Al Gentry, a gangling figure in a grimy t-shirt and jeans frayed from chronic tree-climbing, was a botanist whose strategy toward all hazards was to pretend that they didn't exist. At one point, a tree came crashing down beside him after he lost his footing on a slope. Still on his back, he reached out for an orchid growing on the trunk and said, "Oh, that's Gongora," as casually as if he had just spotted an old friend ona city street.

The team's ornithologist, Ted Parker, specialized in identifying bird species by sound alone. He started his work day before dawn, standing in the rain under a faded umbrella, his Converse sunk to their high-tops in mud, whispering into a microcassette recorder about what he was hearing: "Scarlet-rumped cacique … a fasciated antshrike … two more pairs of Myrmeciza immaculata counter-singing. Dysithamnus puncticeps chorus, male and female …"

Gentry and Parker come to mind just now because I've been thinking about how often naturalists have died in the pursuit of new species. A couple of years after that trip, the two of them were back in the same region making an overflight when their pilot became disoriented in the clouds and

flew into a mountaintop forest. They lingered there overnight, trapped in the wreckage, then died in the morning. "It was beautiful forest," a survivor, Parker's fiancée, later told a reporter, "and they were very happy. Lots of birds."

In truth, the history of biological discovery is a chronicle of such hazards faced not just willingly, but with a kind of joy. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, young naturalists routinely shipped out for destinations that must have seemed almost as remote as the moon is to us now, often traveling not for days, but for months or years. They went of course without GPS devices, or anti-malarial drugs, or any of the other safety measures we now consider routine.

Disease was the unrelenting killer. But death also came by drowning, shipwreck, gun accidents, snakebites, animal attacks, arsenic poisoning, ritual beheading, or almost any other means you care to name. In California on his honeymoon, one birder rigged a safety rope and climbed a tall pine tree to reach a nest. But the rope slipped when he fell and he choked to death as his bride looked on. On expeditions to what is now Indonesia for the Dutch Natural History Commission, 11 naturalists died over a period of 30 years. Zoologist Gerrit van Raalten, for instance, miraculously survived an attack by a Javan rhino, only to succumb a few years later to one of the usual ignominious tropical diseases. Heinrich Macklot became so enraged, on seeing his collections destroyed by fire during a Chinese insurgency in Java, that he launched a counterattack, in which he was speared to death. And yet other naturalists soon followed to take up the cause. (See slide show.)

Survival had its own perils: Rumphius, a seventeenth century naturalist in the East Indies, was struck blind at 42, lost his wife and daughter to an earthquake, saw his collections destroyed by fire, sent off the first half of his magnum opus on a ship that sank, and finally, after re-doing his work, found that his employer meant to keep it proprietary. (Happily, Rumphius's Ambonese Herbal will be published in English for the first time this spring, only 300 years too late.)

No doubt the species seekers undertook such risks partly for the adventure. ("Hunted by a tiger when moth-catching," one wrote. "Hunt tigers myself.") They also clearly loved the natural world. "I trembled with excitement as I saw it coming majestically toward me," Alfred Russel Wallace wrote, of a spectacular butterfly in the East Indies, "& could hardly believeI had really obtained it till I had taken it out

Wallace's prize butterfly

of my net and gazed upon its gorgeous wings of velvet black & brilliant green, its golden body & crimson breast … I have certainly never seen a more gorgeous insect." Naturalists were also caught up body and soul in the great intellectual enterprise of collecting, classifying, and coming to terms with the diversity of life on Earth.

It would be difficult to overstate how profoundly they changed the world along the way. Many of us are alive today, for instance, because naturalists identified obscure species that later turned out to cause malaria, yellow fever, typhus, and other epidemic diseases; other species provided treatments and cures. And a month after capturing that butterfly, Wallace pulled together the ideas that had been piling up during his years of field work and, trembling with malarial fever, wrote Darwin the proposal that would become their joint theory of evolution by natural selection.

This brings me to a small proposal: We go to great lengths commemorating soldiers who have died fighting wars for their countries. Why not do the same for the naturalists who still sometimes give up everything in the effort to understand life? (Neither would diminish the sacrifice of the other. In fact, many early naturalists were also soldiers, or, like Darwin aboard HMS. Beagle, were embedded with military expeditions.) With that in mind, I constructed a very preliminary Naturalists' Wall of the Dead for my book The Species Seekers, to at least assemble the names in one place.

But it also occurs to me that they might prefer to be remembered some other way than on a stone monument, or on paper So here is another idea: On their first trip as part of Conservation International's Rapid Assessment Program, Gentry and Parker helped bring international attention to an Amazonian region of incredible, and unsuspected, diversity. (Parker found 16 parrot species there and projected that it might be home to 11 percent of all bird species on Earth.) As a result in 1995, Bolivia created the Madidi National Park, protecting 4.5 million acres, an area the size of New Jersey, and all the species within it. Peru soon designated the adjacent slope of the Andes as the Bahuaja-Sonene National Park, protecting an additional 802,750 acres.

Like many species seekers, Gentry and Parker did not live to see their discoveries bear fruit. But I am pretty sure that this would be their idea of a fitting memorial.

Honoring the dead is good. We can start by protecting the living.

Dying for Life

The second column in my "Specimens" series, based on my book The Species Seekers, appears today in the New York Times

Almost 20 years ago now, in western Ecuador, I traveled with a team of extraordinary biologists studying a remnant of forest as it was being hacked down around us. Al Gentry, a gangling figure in a grimy t-shirt and jeans frayed from chronic tree-climbing, was a botanist whose strategy toward all hazards was to pretend that they didn't exist. At one point, a tree came crashing down beside him after he lost his footing on a slope. Still on his back, he reached out for an orchid growing on the trunk and said, "Oh, that's Gongora," as casually as if he had just spotted an old friend on a city street.

The team's ornithologist, Ted Parker, specialized in identifying bird species by sound alone. He started his work day before dawn, standing in the rain under a faded umbrella, his Converse sunk to their high-tops in mud, whispering into a microcassette recorder about what he was hearing: "Scarlet-rumped cacique … a fasciated antshrike … two more pairs of Myrmeciza immaculata counter-singing. Dysithamnus puncticeps chorus, male and female …"

Gentry and Parker come to mind just now because I've been thinking about how often naturalists have died in the pursuit of new species. A couple of years after that trip, the two of them were back in the same region making an overflight when their pilot became disoriented in the clouds and flew into a mountaintop forest. They lingered there overnight, trapped in the wreckage, then died in the morning. "It was beautiful forest," a survivor, Parker's fiancée, later told a reporter, "and they were very happy. Lots of birds."

In truth, the history of biological discovery is a chronicle of such hazards faced not just willingly, but with a kind of joy. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, young naturalists routinely shipped out for destinations that must have seemed almost as remote as the moon is to us now, often traveling not for days, but for months or years. They went of course without GPS devices, or anti-malarial drugs, or any of the other safety measures we now consider routine.

Disease was the unrelenting killer. But death also came by drowning, shipwreck, gun accidents, snakebites, animal attacks, arsenic poisoning, ritual beheading, or almost any other means you care to name. In California on his honeymoon, one birder rigged a safety rope and climbed a tall pine tree to reach a nest. But the rope slipped when he fell and he choked to death as his bride looked on. On expeditions to what is now Indonesia for the Dutch Natural History Commission, 11 naturalists died over a period of 30 years. Zoologist Gerrit van Raalten, for instance, miraculously survived an attack by a Javan rhino, only to succumb a few years later to one of the usual ignominious tropical diseases. Heinrich Macklot became so enraged, on seeing his collections destroyed by fire during a Chinese insurgency in Java, that he launched a counterattack, in which he was speared to death. And yet other naturalists soon followed to take up the cause. (See slide show.)

Members of the Dutch Commission on route to New Guinea

Survival had its own perils: Rumphius, a seventeenth century naturalist in the East Indies, was struck blind at 42, lost his wife and daughter to an earthquake, saw his collections destroyed by fire, sent off the first half of his magnum opus on a ship that sank, and finally, after re-doing his work, found that his employer meant to keep it proprietary. (Happily, Rumphius's Ambonese Herbal will be published in English for the first time this spring, only 300 years too late.)

No doubt the species seekers undertook such risks partly for the adventure. ("Hunted by a tiger when moth-catching," one wrote. "Hunt tigers myself.") They also clearly loved the natural world. "I trembled with excitement as I saw it coming majestically toward me," Alfred Russel Wallace wrote, of a spectacular butterfly in the East Indies, "& could hardly believeI had really obtained it till I had taken it out

Wallace's prize butterfly

of my net and gazed upon its gorgeous wings of velvet black & brilliant green, its golden body & crimson breast … I have certainly never seen a more gorgeous insect." Naturalists were also caught up body and soul in the great intellectual enterprise of collecting, classifying, and coming to terms with the diversity of life on Earth.

It would be difficult to overstate how profoundly they changed the world along the way. Many of us are alive today, for instance, because naturalists identified obscure species that later turned out to cause malaria, yellow fever, typhus, and other epidemic diseases; other species provided treatments and cures. And a month after capturing that butterfly, Wallace pulled together the ideas that had been piling up during his years of field work and, trembling with malarial fever, wrote Darwin the proposal that would become their joint theory of evolution by natural selection.

This brings me to a small proposal: We go to great lengths commemorating soldiers who have died fighting wars for their countries. Why not do the same for the naturalists who still sometimes give up everything in the effort to understand life? (Neither would diminish the sacrifice of the other. In fact, many early naturalists were also soldiers, or, like Darwin aboard HMS. Beagle, were embedded with military expeditions.) With that in mind, I constructed a very preliminary Naturalists' Wall of the Dead for my book The Species Seekers, to at least assemble the names in one place.

But it also occurs to me that they might prefer to be remembered some other way than on a stone monument, or on paper So here is another idea: On their first trip as part of Conservation International's Rapid Assessment Program, Gentry and Parker helped bring international attention to an Amazonian region of incredible, and unsuspected, diversity. (Parker found 16 parrot species there and projected that it might be home to 11 percent of all bird species on Earth.) As a result in 1995, Bolivia created the Madidi National Park, protecting 4.5 million acres, an area the size of New Jersey, and all the species within it. Peru soon designated the adjacent slope of the Andes as the Bahuaja-Sonene National Park, protecting an additional 802,750 acres.

Like many species seekers, Gentry and Parker did not live to see their discoveries bear fruit. But I am pretty sure that this would be their idea of a fitting memorial.

Honoring the dead is good. We can start by protecting the living.

January 14, 2011

The Wall of the Dead

We go to great lengths commemorating soldiers who have died fighting wars for their countries. Why not do the same for the naturalists who still sometimes give up everything in the effort to understand life? Neither would diminish the sacrifice of the other. In fact, many early naturalists were also soldiers, or, like Darwin aboard HMS. Beagle, were embedded with military expeditions.

With that in mind, I have started to construct a very preliminary Naturalists' Wall of the Dead, to at least assemble the names in one place. If I have missed someone, or made other mistakes, please suggest changes in the comments.

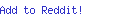

Akeley

Akeley, Carl (1864–1926), naturalist-taxidermist for the American Museum of Natural History, age 62, while collecting mammals in the eastern Congo, of dysentery.

Alexander, Capt. Boyd (1873–1910), explorer and ornithologist, age 47, murdered in what is now Chad.

Anderson, William (1750–1778), surgeon-naturalist on Cook's second and third voyages, at sea, age 28, possibly from scurvy.

Banister, John (1650–1692), British naturalist and clergyman, of a gunshot wound, age 42, while exploring in Virginia.

Batty, Joseph H. (?–1906), taxidermist and specimen hunter recently accused of fraudulent practices, "killed instantly by the accidental discharge of his gun," age unknown, in Mexico.

Bernstein, Heinrich Agathon (1828–1865), German physician and collector of birds and mammals, age 36, on the island of Batanta off New Guinea, cause unknown.

Biermann, Adolph (?–1880), curator of the Calcutta Botanical Garden, survived attack by tiger while walking in garden but succumbed a year later, age unknown, to cholera.

Boerlage, Jacob Gijsbert (1849–1900), Dutch botanist on his 51st birthday, on a botanical expedition to the Moluccas to identify plants described by Rumphius, cause unknown.

Boie, Heinrich (1784–1827), German ornithologist, age 33, of "gall fever," in Java, one of a long succession of naturalists to die in the service of the Dutch Natural History Commission to the East Indies.

Bowman, David (1838–1868), Scottish plant collector, robbed of his specimens in Colombia and said to have died of "mortification," but more likely from dysentery, age 30, in Bogota.

Buddingh, Johan Adriaan (1840–1870), Dutch civil servant and amateur collector for the Leiden Museum, age 30, in Batavia (Jakarta), Java, cause unknown.

Cahoon, John Cyrus (1863–1891), American ornithologist and field naturalist, fell off a sea cliff, age 28, in Newfoundland.

Cassin, John (1813–1869), American ornithologist who described 198 new species, age 55, apparently of arsenic poisoning.

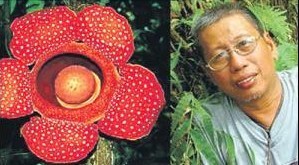

Co and pitcher plant named in his memory

Co, Leonardo (19tk-2010). Filipino botanist, age 56, gunned down with two assistants in what the military claimed was a gun battle with rebel forces, while collecting seedlings of endangered trees for replanting.

Cralitz, H. (?–1637), German physician and naturalist on a Dutch West Indies Company expedition, soon after arrival in Brazil, cause unknown.

Craven, Ian (1962–1993), ornithologist, age 31, plane crash in Irian Jaya.

Dawson, Elmer Yale (1918–1966), Smithsonian Institution phycologist, age 48, drowned while diving for seaweeds in the Red Sea.

Doherty, William (1857–1901), American lepidopterist and specimen hunter for Walter Rothschild, age 44, of dysentery, in Kenya's Aberdare Mountains.

Douglas, David (1799–1834), Scottish botanist and explorer, age 35, fell into a pit trap already occupied by a bull, in Hawaii.

Dutreuil de Rhins, Jules Léon (1846–1894), French explorer, age 48, murdered in Eastern Tibet.

Eickwort, George Campbell (1949–1994), hymenopterist, age 45, car accident in Jamaica.

Feilner, Sgt. John (?–1864), ornithologist, age unknown, surprised and killed by Sioux while collecting ahead of his U.S. Army expedition in the Dakotas.

Fonseca, Rene Marcelo (1976–2004), Ecuadorian mammalogist, age 28, car accident.

Forsskål, Pehr (1732–1763), Helsinki-born "apostle" of Linnaeus's, age 31, of malaria in what is now Yemen.

Gambel, William (1823–1849), American naturalist, namesake of Gambel's quail, age 26, of typhoid fever in the Sierra Nevada.

Gentry, Al (1945–1993), botanist, age 48, plane crash in the mountains of Ecuador.

Gilbert, John (1810?–1845), British naturalist and explorer, collected Australian mammals and birds for John Gould until killed by a spear, age 35, during a nighttime raid on his camp by Aborigines.

Grant, Harold J. (1921–1966), American entomologist, age 45, drowned on an expedition collecting grasshoppers in Trinidad.

Griffith, William (1810–1845), British botanist in India and Afghanistan, age 34, of malaria.

Harrisson, Tom (1912–1976), British anthropologist and ornithologist, age 64, bus accident in Thailand.

Hasselquist, Fredric (1722–1752), Swedish "apostle" of Linnaeus's, made extensive collections in the Middle East, age 30, near Smyrna, cause unknown.

Van Hasselt

Hasselt, Johann Coenraad van (1797–1823), Dutch ornithologist, age 26, of an unknown tropical illness in Java.

Helfer, Johan Wilhelm (1810–1840), Austrian naturalist, age 29, murdered in the Andaman Islands.

Hemphill, Henry (1830–1914), American naturalist studying shells, age 84, of arsenic poisoning.

Hemprich, Wilhelm (1796–1825), surgeon in the Prussian army, naturalist, leader of a five-year expedition to Egypt and nearby countries, collecting 3000 plant and 4000 animal species, on which nine team members died, including Hemprich, age 28, probably of malaria, in Eritrea.

Hendee, Russell W. (1899–1929), mammalogist collecting for the Field Museum's Kelley-Roosevelts Expedition, age 30, of malaria in Vientiane.

Jacquemont, Victor (1801–1832), French botanist in India, age 31, of dysentery or malaria.

Kingsley, Mary H. (1862–1900), British explorer, ichthyologist, age 37, of typhoid fever in South Africa.

Köenig, Johann Gerhard (1728–1785), Polish-born physician and student of Linnaeus who introduced the Linnaean system to India, age 57, cause unknown.

Kramer, Gustav (1910–1959), German ornithologist, was attempting to capture young rock doves from a nest when he lost his footing and fell to his death, age 49, in southern Italy.

Kuhl

Kuhl, Heinrich (1797–1821), German ornithologist, age 23, in Java, of an unknown tropical disease.

Leitner, Edward F. (1812–1838), German-born physician and botanist, collector for Audubon and Bachman, shot by Indians, age 26, near Jupiter Inlet, Florida.

Macklot, Heinrich (1799–1832), naturalist, was so enraged when insurgents burned down his house, with all of his collections, that he organized a revenge attack and was speared to death, age 33, in Java.

Marcgraf, George (1610–1644), German physician and naturalist on a Dutch West Indies expedition, age 34, probably of malaria, in Brazil.

Meyer, Frank N. (1875–1918), American plant explorer, made four expeditions to China. Heading homeward down the Yangtze River at a time of political turmoil, he disappeared, age 43, from his ship and his body was recovered a week later.

Moorcroft, William (1765–1825), British veterinary surgeon and plant-collector in Tibet and Kashmir, also reputed to be a secret agent, age 60, murdered in Afghanistan.

Natterer, Johann (1787–1843), Vienna-born zoologist, survived 18 years collecting in Brazil, but died at home, age 56, of pulmonary hemorrhage, while working up his extensive collection.

van Oort

Oort, Pieter van (1804–1834), artist who made numerous illustrations of landscapes, people, animals, and plants for the Dutch Natural History Commission in the East Indies, age 30, in Sumatra, of malaria.

Pambu (dates unknown), a Lepcha collector working with William Doherty, "murdered by the savages" in Papua New Guinea.

Parker, Ted (1953–1993), American ornithologist, age 40, killed in a plane crash in the mountains of Ecuador.

Parkinson, Sydney (1745–1771), artist on Cook's Endeavour, at sea, age 26, of dysentery.

Peale, Raphaelle (1774–1825), American artist and naturalist, age 51, of arsenic and mercury poisoning from his taxidermic work in the family museum.

Przhevalsky, Nikolai Mikhaylovich (1839–1888), Polish-Russian explorer, discoverer of only wild horse species, of typhus, age 49, in Kyrgyzstan.

Raalten, Gerrit van (1797–1829), Dutch artist with naturalists in Java, survived a rhino attack but succumbed, age 32, to fever.

Raddi, Giuseppe (1770–1829), Italian botanist, herpetologist in Brazil, age 59, of dysentery at Rhodes, during an expedition to the Nile.

Schlagintweit Brothers

Schlagintweit, Adolf (1829–1857), one of five German brothers who became naturalists and explorers, beheaded as a spy, age 28, in Kashgar.

Schweigger, August Friedrich (1783–1821), German naturalist, age 38, murdered by his guide on a research trip in Sicily.

Seetzen, Ulrich. J. (1767–1811), German explorer and naturalist specializing in snakes and frogs, traveled in the Middle East disguised as a beggar. Accused of stealing cultural treasures, he was poisoned to death, age 44, apparently on the order of an Imam in what is now Yemen.

Slowinski, Joseph (1962–2001), herpetologist, age 38, in northern Burma, snakebite.

Smithwick, Richard P. (1887–1909), American ornithologist, smothered to death while digging his way into a soft bank to raid a Belted Kingfisher nest, found "with his feet only projecting through the sand," age 22, in Virginia.

Stalker, Wilfred (1879–1910), British collector of natural history specimens in Southeast Asia, drowned, age 31, on the British Ornithological Union's 1909 expedition to New Guinea.

Stokes, William (?–1873), "sailor boy" on HMS Challenger, killed when block from oceanographers' dredge tore loose and hit him.

Stoliczka, Ferdinand (1838–1874), Czech paleontologist and naturalist, age 36, of altitude sickness while crossing the Himalayas in Ladakh, in India.

Suhm, Rudolf von Willemoes (1847–1875), German, the youngest of the "Scientifics," dubbed the baron by crew of HMS Challenger, age 28, of erysipelas, an acute streptococcus infection.

Swain, Ralph B. (1912–1953), entomologist, ornithologist, botanist, age 41, murdered by bandits in Mexico.

Thorbjarnarson, John (1957–2010), American herpetologist specializing in crocodiles, age 52, of malaria, in India.

Townsend

Townsend, John Kirk (1809 –1851), American physician and naturalist, age 42, of arsenic poisoning.

Tungkyitbo (?–1891), Lepcha collector working with William Doherty, hospitalized in Java for unknown condition, then died at sea.

Wallace, Herbert (1828–1850), entomologist, age 22, of yellow fever in the Amazon.

Walsh, Benjamin (1808–1869), the first state entomologist in Illinois, age 61, after losing his foot in a train accident.

White, Samuel (1835–1880), Australian ornithologist, age 45, of pneumonia or fever during an expedition to the Aru Islands.

Whitehead, John (1860–1899), British collector of natural history specimens in Southeast Asia, age 39, of fever in Hainan, China.

January 12, 2011

Species Seekers, Rogues, and Heroes in the News

Over the weekend, WAMU's "Animal House" posted an entertaining interview about The Species Seekers:

Acclaimed science writer Richard Conniff tells the story of a new breed of adventurer in the 18th century. They traveled to the most perilous corners of the planet and brought back astonishing new life forms. We learn about how the pantheon of life they discovered changed man's view of his place on earth.

You can listen here.

Also this weekend, The Los Angeles Times gave The Species Seekers a lovely review:

Conniff's book is filled with rogues and heroes, and their not infrequent overlapping explorations make for entertaining reading.

Here's what other reviewers have had to say: The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth by Richard Conniff isis "a swashbuckling romp" that "brilliantly evokes that just-before Darwin era" (BBC Focus) and "an enduring story bursting at the seams with intriguing, fantastical and disturbing anecdotes" (New Scientist). "This beautifully written book has the verve of an adventure story" (Wall St. Journal).