Richard Conniff's Blog, page 114

December 10, 2010

Worn Does Not Mean Worthless

No longer sharpest tool in shed

"Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise." So says Proverbs 6:6-8. And today's lesson, my brothers and sisters of the Boom Baby Generation, comes from leafcutter ants, those beautiful creatures who parade through the rainforest with leaf fragments held up over their heads like placards.

Apparently, a lifetime of cutting up leaves can make an ant's mandibles dull. But they don't simply give up, go back to the nest, and rock out their days on the front porch. (Possibly their sister ants with mandibles still sharp would cut them up and cart the little pieces out to the nearest ant graveyard)

Instead, they switch to different jobs for which their other skills are still quite adequate.

Here's the press release (and, damn, I wish these press releases would do the right thing and include the actual citation for the article):

Newswise — When their razor-sharp mandibles wear out, leaf-cutter ants change jobs, remaining productive while letting their more efficient sisters take over cutting, say researchers from two Oregon universities.

Their study — appearing online ahead of regular publication in the journal Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology — provides a glimpse of nature's way of providing for its displaced workers.

"This study demonstrates an advantage of social living that we are familiar with — humans that can no longer do certain tasks can still make very worthwhile contributions to society, even if they could not live on their own," said the paper's lead author Robert Schofield, a scientist at the University of Oregon. "While division of labor is well documented in social insects, this is the first suggestion that some social insects stop performing certain tasks because they are no longer as good at them as they used to be. As social organisms, these ants have the luxury of being able to leave the cutting task to their more efficient sisters."

Leaf-cutter ants slice leaves, carry pieces back to the underground nest for further processing and, like tiny mushroom farmers, grow an edible fungus on the resulting substrate. The ants doing the cutting are usually members of the generalized forager caste, one of four size-based behavioral castes of workers. The foragers are second in size to the majors, the large workers that protect the colony and do heavy clearing work on the trails constructed to connect the nest to the leaf sources. In addition to cutting, the foragers transport the cuttings, scout for new resources and also help protect the colony.

"Cutting leaves is hard work. Much of the cutting is done with a V-shaped blade between teeth on their mandibles that they use like a tailor who holds a pair of scissors in a fixed V shape to slice through cloth," Schofield said. "This blade starts out as sharp as the sharpest razor blade that humans have developed."

Over time, though, their mandibles slowly dull. It takes longer and requires more energy to get the job done. When it takes an ant about three times as much time and energy to cut out a leaf disc than it would have taken when her blades were sharp, behavior changes, the researchers reported. The cutting ants rest their blades and join the delivery staff, carrying the discs cut from the leaves into their nest.

"Imagine having only two tiny knives to use for your entire life, with no sharpening allowed," Schofield said. "You would want them to be made of the best material possible. You would use them very carefully, but cutting would still get harder and harder as they dulled until you had to rely on others to cut for you. That's what it is like to be a leaf-cutter ant."

The composition of the cutting blades is of particular interest to researchers. The findings support the idea that wear and fracture are big problems for smaller animals. The researchers estimate that, because of wear, the colony spends twice as much energy cutting leaves as it would if all ants had sharp mandibles. This cost should have resulted in an evolutionary pressure to develop materials that resist dulling, the research team noted. The cutting blades are indeed made of a zinc-rich biomaterial that the researchers suspect is wear resistant.

Schofield was lead author of a study published in 2001 that had identified a family of biomaterials present in mandibular teeth, tarsal claws, stings and other such tools of small organisms. In 2009, a team led by Schofield reported that a similar type of substance empowers the claw tips of striped shore crab and is present on the walking legs of Dungeness crabs.

"Humans are just starting to try to engineer tiny machines and tools, and we have a lot still to learn from organisms that have coped with being small for millions of years," Schofield said. "And in addition, it's good to know how important wear is to these ants, because they are agricultural pests, and this research hints that crops that produce high levels of wear might discourage them."

December 9, 2010

Great Species Seekers: The Amazing Mary Kingsley

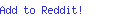

[image error]Late one afternoon in 1895, that rare animal, a female species seeker, was hiking alone through a forest in the interior of Gabon. It was treacherous country. Her guides had pointed out the shredded bark of trees along the forest trail, meaning leopards in the neighborhood. The human inhabitants were also fearsome, said to be cannibals.

But Mary Kingsley was in equal parts self-assured and self-deprecating, an attractive unmarried woman in her 30s with an independent income, roaming footloose over "the white man's grave." Where male explorers often resorted to the chest-thumping language of conquest, she relied instead on her understated wit. She was also unmistakably intrepid.

This time, though, going ahead on her own proved foolish. It was five p.m., and the path through the woods grew indistinct–she could just pick it out. But then she came to a place where it vanished completely. She peered ahead, and thought she saw it resume again on the other side of a clump of brush. So she pushed on—and plunged to the bottom of a 15-foot-deep pit lined with sharpened spikes.

"It is at times like these that you realise the blessing of a good skirt," Kingsley wrote. "Had I paid heed to the advice of many people in England, who ought to have known better … and adopted masculine garments, I should have been spiked to the bone, and done for. Whereas, save for a good many bruises, here I was with the fulness of my skirt tucked under me, sitting on nine ebony spikes some twelve inches long, in comparative comfort, howling lustily to be hauled out. "

Like other naturalists, Kingsley wanted to find new species, and in 1896, she eagerly reported the "verdict" on the haul from her second expedition to West Africa: "one absolutely new fish" and one equally new snake, among other treasures. Kingsley was relieved, "for I was beginning to fear I was an utter wind bag."

You can read more about Mary Kingsley in Richard Conniff's new book The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth, praised by New Scientist as "an enduring story bursting at the seams with intriguing, fantastical and disturbing anecdotes."

Amazonian Terrors

Species Seeker extraordinaire Henry Walter Bates reported that Amazon boatmen "live in constant dread of the 'terras cahidas'." What are they?

1. Earthquakes.

2. Giant crocodiles.

3. Landslips.

4. Floating logs.

And the answer is:[image error]

Landslips.

[image error]Canoemen, Bates wrote, "live in constant dread of the 'terras cahidas,' or landslips, which occasionally take place along the steep earthy banks, especially when the waters are rising." He was inclined to dismiss the stories that "these avalanches of earth and trees" could swamp even larger vessels. But one morning before dawn "an unusual sound resembling the roar of artillery" startled him out of his sleep. It felt at first like an earthquake, "for, though the night was breathlessly calm, the broad river was much agitated and the vessel rolled heavily."

The "thundering peal" of explosions rolled back and forth along the river, with "a long, continued dull rumbling" in the intervals. When day broke, he looked to the opposite riverbank, three miles off, and saw that "Large masses of forest, including trees of colossal size, probably 200 feet in height, were rocking to and fro, and falling headlong one after the other into the water." The impact sent out a sort of Amazonian tsunami that undermined other parts of the bank, extending the landslip over a mile or two of coast. "And thus the crashes continued, swaying to and fro, with little prospect of a termination" as their boat went out of sight up river two hours later.

December 8, 2010

A Revolution in the Ways We Live and Die

One night in 1877, in a squalid port city on the southeastern coast of China, a Scottish doctor named Patrick Manson performed a small experiment that would soon revolutionize the ways we live and die. What was his subject?

1. A dog.

2. A mosquito.

3. A human being.

4. A laboratory rat.

And the answer is:

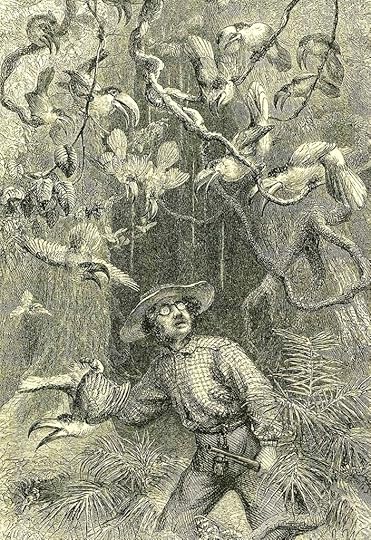

Patrick Manson performed a small experiment with mosquitoes. The scope of the test was limited and the design badly flawed. But it was the beginning of a spectacular quarter century in which the work of the species seekers would bear fruit, enabling humans for the first time to control diseases that had plagued them forever. His experiment focused on elephantiasis, a common disorder in the tropics that he suspected was caused by parasitic filarial worms.

Patrick Manson performed a small experiment with mosquitoes. The scope of the test was limited and the design badly flawed. But it was the beginning of a spectacular quarter century in which the work of the species seekers would bear fruit, enabling humans for the first time to control diseases that had plagued them forever. His experiment focused on elephantiasis, a common disorder in the tropics that he suspected was caused by parasitic filarial worms.

He also hypothesized that the worms were passed from one individual host to another by a blood-sucking insect. Somehow, from examining what was essentially a paste of mashed filarial-infected mosquitoes, Manson also discerned what happened next: Newly liberated from their first host, microfilariae passed through the mosquito's abdominal lining and took up residence in the muscles of its thoracic cavity. There they continued to develop, "manifestly … on the road to a new human host."

He had discovered "a new and revolutionary concept," according to medical historian Eli Chernin–"that certain bloodsucking arthropods can transmit human disease." It would eventually save millions of lives—arguably, millions every year in the modern era–and immortalize Manson as "the father of modern tropical medicine."

There's a lot more to this story—you can read about it in The Species Seekers

December 7, 2010

Ralph Nader Plays Santa with my Natural History of the Rich

Well, this is very odd. Ralph Nader has come up with a clever idea called Christmas-by-the Box. He'll sell you 100 copies of some of his favorite books for $100 (shipping included) and you give them away to friends and strangers. My Natural History of the Rich: A Field Guide (hardcover from W.W. Norton) is on Ralph's list.

Well, this is very odd. Ralph Nader has come up with a clever idea called Christmas-by-the Box. He'll sell you 100 copies of some of his favorite books for $100 (shipping included) and you give them away to friends and strangers. My Natural History of the Rich: A Field Guide (hardcover from W.W. Norton) is on Ralph's list.

O.k., I can hear you cynics grumbling that he's just clearing out his stock of books purchased on remainder. But, hey, be nice, it's coming up on Christmas!

That book has attracted a remarkably diverse assortment of admirers, not just Nader but Dominick Dunne and even Town & Country magazine: "This book…may change for ever our perception of the urge to make money." — The Financial Times "Clever, perceptive and unfailingly interesting." — Jonathan Yardley, Washington Post "Droll and delightful….Conniff's charm and fun-loving approach make his book a pleasure from start to finish." — New York Sun "It is anecdotal, witty, and wonderfully informative." — Dominick Dunne "A witty compendium of gossip, anecdotes, history and sociobiological research." — Town and Country

Here's Santa Ralph's sales pitch:

From: Ralph Nader

Subject: Bookstore By The Box

Date: Tuesday, December 7, 2010, 12:33 PM

Let's try a quick experiment that no one can stop us from conducting.

It is an important experiment that can spread rapidly and start something of consequence that will be fun and gain attention.

Let's call it Bookstore by the Box.

Here's how it works.

I'll give you my list of book titles for your selection.

Each book title–see attached list–fills a box unopened from the publisher's warehouse.

The average number of these book titles is twenty four.

Twenty four books of the same title.

No assortment.

You can select any box for purchase–$100 per box–(this includes shipping costs.)

On arrival, you can distribute your box or boxes either for free or at a small price per book-as you choose.

You can give them to anyone you want-individual or institutional, such as school classes or libraries.

Then you immediately become a BOOKSHAKER.

A BOOKSHAKER is a person who gives books away to family, friends and co-workers or utilizes them for door prizes at parties, fund-raising for neighborhood or community organizations, mentoring programs, libraries, texts for study groups or classrooms.

When you receive the books, you make the call.

Most people do not go around giving out books to people they know or would like to know.

A gift of one book-sure-but many books that you like of the same title-no tradition there.

So, we start a tradition and all the wonderful associations that go with it.

Like-starting good conversations about subjects-the beginning of all change starts with conversations.

Like-respecting peoples' intelligence, including those who argue with you, when you give them a book which makes for a healthy reciprocity.

Like-a lasting way to gift your friends during the upcoming Holiday season.

Books last, unlike a box of chocolates.

Like-beginning a spreading method of book distribution that is decentralized, anywhere and everywhere, uncontrollable by giant box stores or excessive cost.

Like-building small communities of intelligent deliberation and self-education.

Like-proving that the gift relationship is far more fruitful than a commercial one for exchanges that matter.

Like-replacing some small talk with big talk that gets away from sound bytes and kneejerk reactions.

Like-Until you've experienced the joy of giving books away, you cannot imagine how rewarding it is.

Like-Enough Already!

Go to the next page and select your favorite books by the box of 24 (twenty four) books of the same title.

Check out the list.

And click here to proceed to the Bookstore by the Box.

Thank you for spreading the word and being such a good sport.

As ever,

Ralph Nader

PS: Please pass the word to friends and family.

The Bookstore by the Box offer ends midnight December 20, 2010.

Click here to make your purchase now.

Selection of books-24 or more to a box of the same title (While Supplies Last)

(HC indicates hard cover. PB indicates paperback.)

1. Cruel and Unusual by Mark Crispin Miller (2004) HC (Searing critique of Bush/Cheney's New World Order)

2. Command Performance by Jane Alexander (2000) PB (An Actress in the Theater of Washington Politics)

3. The Cheating of America by Charles Lewis and Bill Allison (2002) HC (A galvanizing journey about tax avoidance and evasion by the Super Rich and What You Can Do About It)

4. Democracy at Risk by Jeff Gates (2001) HC (Rescuing Main Street from Wall Street)

5. The Good Years by Walter Lord (1960) PB (The best-selling rendition of America 1900 to 1914)

6. Huey Long by Harry T. Williams (1981) PB (The classic biography of the "Kingfish" and the tumultuous politics of the Twenties and Thirties from Louisiana to FDR's Washington, D.C.)

7. Natural History of the Rich by Richard Conniff (2003) HC (Just what you can expect from the Upper Crust)

8. Women Pay More by Frances Cerra and Marcia Carroll (1993) PB (And How to Put A Stop to It-eye-opening for the men, but not the women)

9. Freedom for the Thought That We Hate by Anthony Lewis (2008) HC (A popular biography of the First Amendment and the stories and lawsuits that give it judicial spine)

10. Change for America ed. By Mark Green (2009) PB (Liberal policies-the whole nine yards)

11. We Who Dared to Say No to War by Murray Polner (2008) PB

12. Crimes of War by Richard Falk (2006) PB

13. Too Close to Call by Jeffrey Toobin. (2002) HC (The Thirty-Six-Day Battle to Decide the 2000 Election)

14. Uncovering Clinton by Michael Isikoff (2000) PB (A Reporter's Story of uncovering the Lewinsky Scandal)

15. I Hate George W. Bush Reader by Clint Willis, ed. (2004) PB (part of the infelicitously titled "I HateŠ series) (Leading progressives Molly Ivins, William GreiderŠlet loose on "Shrub")

16. The Triumph of Meanness by Nicolaus Mills (1997) HC (America's War Against Its Better Self–returning with a vengeance in 2011.)

17. Against the Beast by John Nichols, ed. (2004) PB (A Documentary History of American Opposition to Empire)

18. American Rebels by Jack Newfield, ed. (2004) PB

19. Freedom's Power by Paul Starr (2007) HC (The True Historic Force of Liberalism)

20. Grassroots Gardening by Donna Schaper (2007) PB (Gardens for sustaining activism)

21. Kidding Around Boston by Helen Byers (2000) PB (What to Do, Where to Go, and How to Have Fun in Boston)

22. Selling Women Short by Liza Featherstone (2005) PB (The Landmark Battle for Workers' Rights at Wal-Mart)

23. The Cigarette Century by Allan M. Brandt (2009) HC (The Rise, Fall and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America)

24. The Jonathan Schell Reader by Jonathan Schell (2004) PB (On the United States at War and the Fate of the Earth)

25. The Ten Minute Activist by Mission Collective (2006) PB (Easy Ways to Take Back the Planet)

26. University Inc. by Jennifer Washburn (2006) HC (The corporate corruption of Higher Education)

27. Vermont Hiking by Michael Lanza (2005) PB (Day Hikes, Kid-Friendly Trails and Backpacking Treks)

December 2, 2010

Making a Flap in the Scientific World

Trumpeter swan taking off. (photo by Michael Dunn)

In what evolutionary controversy did the Trumpeter swan serve as evidence?

1. Are human races each a different species?

2. Are birds the modern descendants of dinosaurs?

3. Which came first: the chicken or the egg?

4. Is long-distance migration an innate or learned behavior?

And the answer is …

[image error]

A minister on the side of science

Social reformer and Audubon collaborator (Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America) Rev. John Bachman of Charleston, South Carolina, was a thoroughly trained naturalist and knew his way around the species question. Bachman carefully avoided religious arguments in making the case that all human races belong to a single species.

Instead, he relied on the same scientific methods used to separate one species from another in the animal world. He pointed out, for instance, that the whooper swan and the trumpeter swan resemble each other so closely that they were long regarded as one species. Then dissection revealed significant differences in bone count and other internal structures, causing naturalists to split them apart as two separate species.

"Let us now apply this rigid rule of investigation to the anatomy of the bones and the physiology of the various organs in the different races of men," he suggested. Then he did the numbers: The human breast bone consists of eight pieces in infancy, three pieces in youth, and a single piece in old age–regardless of race. The human skull contains eight bones, with four bones in the ear–again regardless of race. The number of milk teeth and their adult replacements is identical in all races. Bachman's work influenced Darwin and others who saw the common origin of all humans as essential for evolutionary theory.

Read more about the ugly fight over racial differences and the species question in Chapter Eleven of The Species Seekers by Richard Conniff.

November 20, 2010

A Claw Like a Sledgehammer

The December issue of Smithsonian Magazine, in readers' mailboxes today, features this interesting bit of behavior by mantis shrimps. The very brief article is by Tom Frail:

NAME: the mantis shrimp *(Neogonodactylus wennerae)*, a coastal crustacean

EATS snails, blasting open their shells with a "raptorial appendage" that is basically a spring-loaded hammer capable of slicing through seawater at 45 m.p.h.

FIGHTS ritual fights with other mantis shrimp to protect its burrow, trading blows to the tail that would shatter mollusk shells and crab carapaces.

LIVES through this punishment because its tail, or telson, dissipates almost 70 percent of each blow's energy. How? A new study has found that the telson is structured to absorb energy like a punching bag, rather than like a trampoline. And the bigger the telson, the bigger the blow it can take. The finding, says lead author Jennifer Taylor of Indiana University-Purdue University at Fort Wayne, suggests that mantis shrimp in ritual combat may be using information from their tails and raptorial appendages to size up opponents before deciding how far to take the fight.

Here's a link to a TED talk by researcher Sheila Patek.

November 19, 2010

Why Roger Ailes Shouldn't Call Other People Nazis

You probably think I'm going to say it's about the pot calling the kettle black. But no. It has to do with a more general rule for acceptable behaviors. This is a short piece I wrote a while ago for Smithsonian. (Background: In case you missed it, Fox News boss Roger Ailes made a snarky half-apology to the Anti-Defamation League for having called NPR execs "Nazis" in the firing of Juan Williams, now employed at Fox. Where, by the way, they routinely obey Benford's Law.)

I like to collect gratuitous opinions served up as laws of social behavior. Murphy's Law ("If anything can go wrong, it will") is the most famous example. But the obscure ones are more fun. Say, for instance, that someone in an argument starts to foam at the mouth. You mildly remark, "What you're saying is a perfect instance of Benford's Law of Controversy," and it will take a Google search for the poor sap him to figure out that you have insulted him: Benford's Law states that passion in any argument is inversely proportional to the amount of real information advanced.

Godwin's Law is also handy. It holds that the longer an argument drags on, the likelier someone will stoop to a Hitler or Nazi analogy. And in common practice, when a rival tries it (other than in appropriate contexts like genocide), you have only to say "Godwin's law," and a trapdoor falls open, plunging him into a pool of hungry crocodiles. Sweet, no?

Sweeter still, these little rules allow us to sound intellectual without necessarily having to do any homework. That's why people are always citing the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Well, it's also the reason they almost always get it wrong. The Uncertainty Principle actually has to do with physics, and let's just say that if you read it, your head will explode. So what's that nice idea about how observation inevitably alters the thing being observed? That's "the observer effect." But nobody calls it that because the absence of a tag like Heisenberg means it lacks smartypants heft. What we really need is the Heisenberg Probability Principle, which states that anybody mentioning Heisenberg is probably a pompous twit. (And may I be the first to plead guilty as charged?)

Well, o.k., it's not just about the pleasures of intellectual one-upmanship. Some of these rules actually hold precious wisdom. Hegel's Paradox, for instance, says, "Man learns from history that man learns nothing from history." And Clarke's First Law, coined by science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, nails the tricky nature of wisdom: "When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible he is almost certainly wrong."

Once in Ireland, I ran across a statement by a nineteenth-century bishop that struck me as particularly profound: "It is almost impossible to exaggerate the complete unimportance of almost everything." I've never been able to track down the source (but that's unimportant). In any case, Sturgeon's Revelation, named after science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon, gives the same idea a nice modern spin: "Ninety percent of everything is crud."

The workplace has spawned more than its share of such obiter dicta (not to mention crud.) Thus the Dilbert Principle says, "The most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least damage: management." But Joy's Law, coined by Sun Microsystems co-founder Bill Joy, also captures every manager's sinking sense of despair: "No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else." Harried tech workers like to trot out Brooks's Law, from software engineer Frederick P. Brooks: "Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later." Or as Brooks also put it, "The bearing of a child takes nine months, no matter how many women are assigned."

Impatient bosses often strike back with Parkinson's Law, which states that "work expands to fill the time allotted for its completion." ("Come on, I know you can get that baby done in eight …") In fact, my annoying editor just showed up at the door to remind me that time's up.

"Don't be such a deadline Nazi," I snapped.

"Godwin's Law," he replied.

***

November 16, 2010

Fear and Herd Behavior

One of my editors, Fen Montaigne of Yale Environment 360 has a new book out about Adelie penguins. It's worth taking a look.

One of my editors, Fen Montaigne of Yale Environment 360 has a new book out about Adelie penguins. It's worth taking a look.

It also reminds me of a brief item I wrote about these penguins in my 2005 book The Ape in the Corner Office:

Fear of predators is one reason so many species practice herd behavior with such blind, fretful enthusiasm.

During a visit in the Antarctic, for instance, Peter Brueggeman of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography sat in the middle of an Adelie penguin traffic jam watching the birds dither at water's edge.

"So what does it take for them to jump in?" Brueggeman wondered, in his online journal. "They watch the water and when a large group of penguins comes swimming into their immediate area, the Adelie penguins start getting very vocal." They jostle, jockey for position, squabble, peck back and forth, bash one another with their flippers, and engage in raucous discussion, followed by "an immediate chain reaction of everyone rushing to jump in the pool all at the same time, no waiting …"

So is all this commotion just the usual mindless negativity, bickering, and herd behavior all too familiar in other two-legged species?

In fact, it is a question of life or death. Hungry leopard seals and orca whales patrol these shorelines in search of penguins for dinner. But penguins need to eat, too, and sooner or later, if they can muster the positivity offset, that means going into the water. If there are already lots of penguins in the water, chances are that the coast is clear. So the dithering crowd on shore all try to do the same thing, jumping in at the exact same moment. Some of them may still get eaten. But this is the reward for social conformity:

Chances are, it'll happen to the other guy.

November 11, 2010

Saving Lives with Genetically Engineered Mosquitoes

It's common to release sterilized males as a means of reducing mosquito populations and preventing human disease. But it didn't work for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which spread dengue and yellow fever. So Nature reports today that genetic engineering has proved a successful alternative.

GM mosquitoes wipe out dengue fever in trial - November 11, 2010

The controlled release of male mosquitoes genetically engineered to be sterile has successfully wiped out dengue fever in a town of around 3000 people, in Grand Cayman, an island in the Caribbean Sea, researchers report.

The release is the first field trial of GM dengue-carrying mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) developed by scientists at Oxitec, a UK-based company founded and part-owned by the University of Oxford. (You can see a video of the release here.) The researchers reported the findings of the study, which ran from May to October this year, on 4 November and briefed journalists about the research at a press meeting today in London.

Dengue fever is a debilitating disease carried by biting female A.aegypti mosquitoes and causing around 25,000 human deaths a year. It mainly occurs in the tropics, but it is spreading to other climes. Paul Reiter, a medical entomology at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, told reporters that a case was reported in Holland around 4 weeks ago, and two cases have been reported in the south of France this year.

Current control methods, including bed nets and insecticides, have proved unsuccessful in controlling the disease. In addition, a vaccine has not yet been developed, and is unlikely to be available for at least 10 years, Reiter said.

Many agricultural pests are controlled through the release of sterile males. They mate with wild females and but do not produce viable offspring, and so the population size falls. If numbers drop far enough, the disease they carry can't spread.

Traditionally, males are sterilised by exposing them to radiation. But A.aegypti proved to be highly sensitive to the radiation, to the extent that they were unable to compete successfully with their wild counterparts for mates. So instead the researchers decided to tweak the mosquitoes' genes to induce sterility. And it worked. The wild females liked the GM males just as much as their fertile counterparts.

They released around 300 million sterile males over the 6 month study period, and found that the wild populations were reduced by 80% as a result – a level sufficient to effectively wipe out dengue fever in the area. "We saw a significant reduction in the target population", Luke Alphey chief scientific officer and founder of Oxitec said.

The GM males are engineered to die off in the wild, and so – Oxitec says – they do not pose a risk by persisting in the environment. The females will only mate with males of the same species, so the genetically modified trait cannot spread to other species.

Alphey said a number of other countries have expressed interest in the technology including Brazil, Panama and Malaysia, the latter of which will begin fields trials in the next few months. (SciDev.net; Malaysian government statement here.)