Richard Conniff's Blog, page 113

January 12, 2011

Life Studies

Over the next two months, I'll be writing a weekly column in The New York Times about the world of species discovery. My ambition isn't just to recapture a lost era of adventure and discovery, but also to show how those early naturalists changed the way we think and live.

Over the next two months, I'll be writing a weekly column in The New York Times about the world of species discovery. My ambition isn't just to recapture a lost era of adventure and discovery, but also to show how those early naturalists changed the way we think and live.

In the corner of our dining room, there's an old half-round cabinet on wheels. It has a handsomely decorated front-panel that swings around on a lazy susan to reveal a collection of whiskey glasses and decanters on the other side. It's what's sometimes called a hide-a-bar, though we use it now mainly as a place to charge our cellphones. We keep it prominently displayed because we like it. But it also oddly embodies the split life of my mother-in-law, from whom we inherited it. And it has lately shaped the course of my own life both as a writer and a son-in-law.

For the first 12 years that I knew her, my wife's mother Janice, a slender, insecure woman, seemingly cowed by life, was an alcoholic. She drank Scotch from late morning onward, like her father before her. Janice allowed, when I started dating her daughter, that she wasn't "too sure" about me, probably with good reason. (I was a young writer with an interest in the natural world, semi-employed, somewhat surly, and a Democrat.) But I was pretty sure about her, and not in a good way. She was from a generation of suburban women whose fathers and husbands did not allow them to have jobs. Instead, she practiced decoupage, a craft or art form in which she meticulously cut out images and then re-arranged them as ornamentation on mirrors, lamps, and furniture, for sale through gift shops and decorators. For her raw material, she cut up beautiful old books of illustrated natural history. I gasped the first time I saw it. I probably also used some indiscreet word like "vandalism."

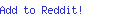

In the 18th and 19th centuries, such books were a crucial tool of the great age of species discovery. Naturalists then did not understand how to preserve specimens. So they often became artists out of necessity, and sometimes described a new species based only on a careful drawing. Artists, caught up in that era's euphoria about new discoveries, also became naturalists. George Stubbs, for instance, once threw on his coat at 10 p.m. and rushed out to bid on a menagerie tiger that had just died. He also spent many long days trying to capture the essence of some astonishing new species as the specimen was rotting and stinking before his eyes. Hand-colored engravings became the means by which the outside world first came to know such marvels of the day as the kangaroo and the platypus. Particularly in Britain, lavishly illustrated books of butterflies and birds — even "A Popular History of British Zoophytes, or Corallines" — became perennial bestsellers.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, such books were a crucial tool of the great age of species discovery. Naturalists then did not understand how to preserve specimens. So they often became artists out of necessity, and sometimes described a new species based only on a careful drawing. Artists, caught up in that era's euphoria about new discoveries, also became naturalists. George Stubbs, for instance, once threw on his coat at 10 p.m. and rushed out to bid on a menagerie tiger that had just died. He also spent many long days trying to capture the essence of some astonishing new species as the specimen was rotting and stinking before his eyes. Hand-colored engravings became the means by which the outside world first came to know such marvels of the day as the kangaroo and the platypus. Particularly in Britain, lavishly illustrated books of butterflies and birds — even "A Popular History of British Zoophytes, or Corallines" — became perennial bestsellers.

And some of them had survived to be carefully disassembled by Janice's decoupage scissors. As a writer, I was frequently away in rain forests or savannas, collecting tarantulas or tracking leopards. But when I came home, those old images of discovery were all around our house, rearranged in beautiful and sometimes disorienting patterns on mirrors, candlesticks, and other objects she had given us. On the front of the hide-a-bar, for instance, a kangaroo stands with its forepaws up, as if in prayer, before a huge "Alice in Wonderland" toadstool. A rat-like marsupial sits upright on a tuber, as if yearning for a hookah, while a litter of youngsters squabble higgledy-piggledy around her pouch. A hummingbird wings down to whisper in the ear of a black man who stands naked, with a sheaf of spears in one hand.

In time, Janice came to regret cutting up old books and prints and switched to color photocopies instead. (One day she also stopped drinking, without a word, and stayed sober for the rest of her life.) But she still had boxes of ruined books, and when she died, they ended up in our attic. A few years ago, I started bringing them down to read in bed, and found them strangely atmospheric and compelling. It wasn't just the illustrations, with the peekaboo holes where species had fallen victim to decoupage. I also liked the language. The nature of classification is to pin things down as exactly as possible, so it was precise and technical–and yet with a kind of poetry: "Shell small, thin, oval, turgid, inequilateral, not gaping. Valves concentrically wrinkled and beautifully striated."

I also got caught up in the adventures of the people doing the discovering, like the British ornithologist in India who got tossed twice by bison, was trampled by a rhinoceros, lost his left arm by jamming it down the throat of a charging leopard, but remained, thank god, a good tennis player, as his obituary noted when he eventually died an old man, in bed.

Sometimes as I was browsing through a book, one of the animal images Janice had cut out, but never used in her art, came slipping out from between the pages: A snake trying to slither back into the living world, an elephant landing weightlessly on my chest, a stag beetle set free, with all its antennae segments and jaw parts and even its claws perfectly intact. It was like living with an ancestor's trophy collection, but with a vestigial knack for meandering. And gradually it dawned on me that my mother-in-law had been mesmerized all along by the same thing that mesmerized me — the natural world in all its strangeness and wonder.

In time, I wrote a book about the wild epoch of discovery that her collection and her decoupage opened up to me, and when "The Species Seekers" came out recently, it was illustrated in part with some of Janice's stray animals, a son-in-law's way of saying, too late, both "Thank you" and "I'm sorry."

January 8, 2011

Keith Richards Defines Homo sapiens as a Social Animal

Keith Richards, of all people, nails the idea of humans as an obligate social species in his memoir, Life:

"I take the view that God, in his infinite wisdom, didn't bother to spring for two joints — heaven and hell. They're the same place, but heaven is when you get everything you want and you meet Mommy and Daddy and your best friends and you all have a hug and a kiss and play your harps. Hell is the same place — no fire and brimstone — but they just all pass by and don't see you. There's nothing, no recognition. You're waving, 'It's me, your father,' but you're invisible. You're on a cloud, you've got your harp, but you can't play with nobody because they don't see you. That's hell." (Keith Richards, Life, p. 431 )

January 7, 2011

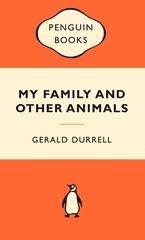

Happy Birthday, Gerald Durrell

I'm not sure he ever discovered a new species, since he was mainly concerned with preserving endangered ones. But Gerald Durrell (born today, 7 Jan 1925, died 30 Jan 1995) inspired my interest in species with his masterpiece My Family And Other Animals, the classic memoir of his childhood years on Corfu. If you have not read it, run out and do so now. It will make you happy.

I'm not sure he ever discovered a new species, since he was mainly concerned with preserving endangered ones. But Gerald Durrell (born today, 7 Jan 1925, died 30 Jan 1995) inspired my interest in species with his masterpiece My Family And Other Animals, the classic memoir of his childhood years on Corfu. If you have not read it, run out and do so now. It will make you happy.

As David Attenborough put it in a 1995 memorial service, "Gerald Durrell was magic." Unblemished by formal education, undaunted by profound alcoholism, Durrell wrote 37 books. He reached millions of television viewers with his unlikely blend of wicked humor and passionate conservation. He founded a zoo on Jersey in the Channel Islands, now widely regarded as one of the world's best. He championed the captive breeding of endangered species, when most zoos regarded the idea as anathema. And he saved whole species from extinction. He did it, moreover, with panache and self-deprecation. Awarded the Order of the British Empire, he modestly averred that the O.B.E. stood for"other buggers' efforts." And on the brink of death, at the age of 70, he summed up his own contribution this way: "Life is like a superlative meal, and the world is the maitre d'hotel. What I'm doing is the equivalent of leaving a reasonable tip.

Part of Durrell's charm as a writer was his seamless mingling of human and animal worlds. He had a knack for anthropomorphizing animals and picking out their individual personalities. On buying a chimp named Chumley (short for Cholmondeley St. John) from a hunter in the Cameroon, he wrote: "When the bargain had been struck and the filthy lucre had changed hands, this simian aristocrat took my hand condescendingly and walked into our living room, peering about him with an ill-concealed disgust, like a duke visiting the kitchen of a sick retainer, determined to be democratic however unsavoury the task."

But Durrell was equally fearless about animalizing his anthropoids, including humans of all ranks. Once, taking Princess Anne on a tour of the Jersey Zoo, he confronted a male mandrill in full sexual display, its bottom like "a newly painted and violently patriotic lavatory seat," all blue on the outer rim, and "virulent sunset scarlet" within. "Wonderful animal, ma'am," Durrell said to the Princess, and then added, "Wouldn't you like to have a behind like that?" Such was Durrell's magic that he didn't merely get away it, but got Princess Anne to become a patron of the zoo.

December 16, 2010

The Species Seekers Chosen 1 of 12 Books of Christmas: "Exceptionally Engaging"

Here's today's review from The Well-Read Naturalist:

Take even a brief look into the histories of those stalwart early naturalists who in the 1600s began fanning out across the globe in search of new forms of life and you will quickly come to understand that theirs were far from normal or average lives. Aside from the physical hardships and deprivations of travel (almost always by ship) in those days – bad food, cramped quarters, fetid water, scurvy and other diseases, drowning, pirates, shipwrecks, etc. – there were, should one survive the trip, myriad dangers peculiar to the destination itself still awaiting the intrepid explorer.

Then, if all went well and specimens were successfully collected without the exploring naturalist succumbing to disease, being killed by less-than-friendly local peoples, or simply getting lost and never heard from again, there was the problem of how to get everything back home. To a reasonable person, such an endeavor would be thought sheer madness; fortunately, as Richard Conniff so well explains in The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth, madmen (and a few women as well) willing to undertake such journeys for the sake of science, fame, riches, sheer curiosity, or some combination of all of these were in no short supply during those early days of scientific exploration.

Not all of them were completely mad of course (although a strong argument could be made that most of them had at least a screw or two not completely tightened); some were simply enthusiastic amateurs posted as soldiers or in the employ of emerging global commercial enterprises such as the British East India Company or its Dutch counterpart who found themselves in far off and exotic locales where throwing a rock at random could likely result in it hitting some manner of creature not yet known in Europe.

Be they who and whatsoever they may have been, Conniff has collected their stories and in The Species Seekers recounts them, together with a goodly portion of the natural histories of their respective discoveries as well as the effects upon the societies of the nations in which collected specimens were studied, exhibited, and in many cases transformed into commercial objects, in a style that is exceptionally engaging, often somewhat playful (his frequent puns will have the attentive reader groaning with appreciation) and wholly intelligible to readers of most all levels of previous knowledge the history of natural history.

Title: The Species Seekers: Heroes, Fools, and the Mad Pursuit of Life on Earth

Author: Richard Conniff (twitter, blog)

Publisher: W. W. Norton

Date of Publication: November 2010

ISBN (clothbound): 978-0-393-06854-2

December 15, 2010

A Coleopterist Goes to War

[image error]Napolean's first aide-de-camp, Col. Pierre Francois Marie Auguste Dejean, was also a coleopterist. What was his specialty?

1. He made precision rifle sights.

2. He collected beetles.

3. He was a battlefield engineer, adept at reading the land by studying the foliage.

4. He designed a new form of artillery.

And the answer is :

[image error]

At the height of the Battle of Alcañiz on May 23 1809, as he was about to give the order for a desperate charge by French troops into the center of the Spanish line, Col. P.F.M.A. Dejean happened to glance down. The air around him was thick with gunpowder and blood, but on a flower beside a stream, he saw something unusual. A beetle. Species unknown. He immediately dismounted, collected it, and pinned the specimen to the cork glued inside his helmet.

Dejean was a count and a battle-tested leader in the Napoleonic armies; he would later become Napoleon's first aide-de-camp. But he was also a coleopterist, a specialist in beetles. His men knew it because many of them carried glass vials for him and had orders to collect anything on six legs that crawled or flew. His enemies knew it, too, and out of respect for the cause of scientific discovery, sent him back vials taken from the dead on the field of battle.

Having collected this latest prize, Dejean swung back up into the saddle and ordered the attack. With bayonets fixed, the massed French forces advanced up the slope toward the Spanish artillery. The gap between them slowly closed, everything tense and quiet.

Then, at the last moment, the cannons let loose a storm of grapeshot into the faces of the attacking line. Hundreds of French soldiers died. Dejean's helmet was shattered by cannon fire. But he and his specimen survived intact. Years later, he would give his prize from Alcañiz a scientific name, by genus and species, Cebrio ustulatus—only to find that someone else had already entered the species in the annals of science under a different name.

Disco Sea Snail (in the Land Down Under)

The light show from Hinea brasiliana. Credit: D. D. Deheyn

They light up inside when touched.

And the light pulsates every hundred milliseconds.

Don't you know the feeling?

Feel the city breakin' and ev'rybody shakin'

and we're stayin' alive, stayin' alive.

Ah, ha, ha, ha, Stayin' Alive.

Or, wait, am I anthropomorphizing? Here's a more sober report from the splendid wallflowers at Livescience:

Tracing the mysterious green flashes of light produced by a sea snail has revealed a creature built to shine from the inside – and with a shell that may be designed for communication as well as protection.

Typically found in tight clusters or groups at rocky shorelines, the clusterwink snail, or Hinea brasiliana, was known to produce light. But scientists like Dimitri Deheyn assumed the sea snails did their light thing just like their pals on the land. Terrestrial snails produce a glowing light from their foot when it's sticking outside the shell.

Nerida Wilson of the Australian Museum in Sydney was working with the Hinea snail when she noticed these bright flashes and not the usual snail glow, so she contacted her colleague Deheyn, of the University of California-San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and sent him some snails. [Sea Creature Releases Glowing Decoy 'Bombs']

The first difference he noticed upon receiving them was that, instead of glowing continuously, they produced light flashes that occurred only when touched.

Not only that, but when the snails retreated into their shells, as snails normally do when startled, they continued to produce light – light that you could see on the outside of the shell.

The flashes are super-fast, Deheyn said, pulsating once every hundred milliseconds or less. And as long as you keep tapping the shell, the snail continues its psychedelic outpouring. "I have records of light flashes for like a half-hour, just flashes, flashes, flashes," Deheyn told LiveScience.

Oh, yeah, baby, show us what you got!

But writer Jeanna Bryner adds this genuine wallflower note: The shell apparently evolved translucence in tandem with the bioluminescence, allowing the snail to communicate "while remaining safe inside its hard shell."

As is all too often the case, we have no idea yet just what this lovely creature is communicating, or why.

You can follow LiveScience Managing Editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner.

December 14, 2010

A Very Colorful Nondescript

Collector Charles Waterton was adept at taxidermy, but notorious for his quirky mountings. His masterpiece was the "Nondescript." What was it?

Collector Charles Waterton was adept at taxidermy, but notorious for his quirky mountings. His masterpiece was the "Nondescript." What was it?

1. A lion concealed for ambush.

2. A human being of bland countenance.

3. The head of a monkey.

4. A polar bear.

And the answer is:

The head of a monkey.[image error]

The "Nondescript," was a distinctly human bust mounted on a wooden stand, frowning, with large brown eyes, anxious upraised brow, and dark skin fringed with reddish hair. Waterton displayed it on the grand staircase at his home, Walton Hall, and also published it as the frontispiece for Wanderings in South America. The rumor went round that he had "shot a native human being" and set it up as an ordinary natural history specimen.

In fact, the "Nondescript" was a howler monkey skillfully manipulated to give "the brute a human formation of face, and to this face an expression of intellectuality." Waterton was doing something that, in the 1820s, would have been more disturbing than either shooting natives or making a mockery of natural science. "Are you not aware," he told an inquisitive friend, "that it is the present fashionable theory that monkeys are shortly to step into our shoes? I have merely foreshadowed future ages or signalised the coming event …"

December 13, 2010

An Arctic Explorer and his Rather Large Find

In 1773, Capt. Constantine John Phipps, 2nd Baron Mulgrave took two ships on a voyage towards the North Pole. What was the mission's outcome?

In 1773, Capt. Constantine John Phipps, 2nd Baron Mulgrave took two ships on a voyage towards the North Pole. What was the mission's outcome?

1. He found the Northwest Passage.

2. He saw a polar bear.

3. He was a spy and brought back early evidence of revolutionary sentiments in the American colonies.

4. He had to be rescued from the ice.

And the answer is

Capt. Constantine Phipps began his military career at the age of 15 aboard the 70 gun HMS Monmouth, and continued to serve his country for the next 33 years, commanding a total of five ships. Phipps' two ships, the Racehorse and the Carcass (with a young Horatio Nelson as midshipman), set sail from Deptford in June of 1773. They never reached the North Pole, being forced back by ice when they got to the Seven Islands, an archipelago in the Arctic north of Norway. They returned to Orford Ness, in Suffolk, in September of the same year. The mission was not, however, a total loss. Phipps was the first European to see a polar bear, which he named Ursus maritimus and described in A Voyage Towards the North Pole Undertaken by His Majesty's Command (1774). Some thought the polar bear belonged in a separate genus, Thalarctos, but subsequent evidence did not support this theory, and Phipps' name stands.

December 12, 2010

Green Penises and Oblivious Biologists

Because they tended to ignore sexual selection as a factor in the evolution of species, generations of male scientists failed to notice what hard-to-miss phenomenon?

1. Displays by the bird of paradise.

2. Musth in elephants.

3. Changing colors in cuttlefish.

4. The love song of the crested bandicoot.

And the answer is:

Musth in elephants.

Hanging low and to the right.

We now recognize that sexual selection accounts for some of the most spectacular displays in the animal kingdom, from the peacock's tail to the courtship dancing of bowerbirds. It's also an important factor in the proliferation of species. Males are continually competing against other males, and evolving lavish new displays to impress females. In most species, females sit back, survey the possibilities, and then do the choosing. Despite Charles Darwin's assertion in The Descent of Man that it isn't enough simply to avoid being killed by predators, famine, or disease–that species also evolve depending on which individuals do better at attracting members of the opposite sex, male biologists managed to ignore this idea for more than a century. They did so because it challenged an orthodoxy more sacrosanct than the biblical account of creation: the idea that males are in charge. But all that began to change with the arrival of women in science.

One hundred and fifty years later, women field biologists, no longer constrained by false modesty, would take a closer look at elephants. Among other extraordinary behaviors, they discovered that male African elephants experience "musth," a recurring period of raging hormones when they belligerently compete for sexual opportunities. The phenomenon should really have been hard to miss. (The researchers actually named one of their study animals "Green Penis," for his outlandish appearance during musth.)

December 10, 2010

Wild Turkey

Why was John J. Audubon resented as an upstart by some established American ornithologists?

1. He failed to pay homage to Alexander Wilson, father of American ornithology.

2. He was a Leatherstocking.

3. He knew nothing about birds.

4. He typically killed birds to obtain his models.

And the answer is:[image error]

Not paying homage to Alexander Wilson.

Audubon first published his Birds of America in England in 1827. It contained 435 hand-colored plates, depicting more than 500 species in spectacularly lifelike poses, and at life size. One French critic hailed it as "a real and palpable vision of the New World." With his rough clothes, shoulder-length hair, and gregarious manner, Audubon himself became an instantaneous celebrity in Europe, as a backwoods New World type. James Fenimore Cooper had just made an international hit with his new novel The Last of the Mohicans. Audubon, a shrewd promoter, capitalized on the sensation by presenting himself as a real-life version of Cooper's hero, the capable frontiersman Leatherstocking.

[image error]Some in the American ornithological establishment, however, were furious at him because Audubon's writings "basely traduced the character of … the illustrious Alexander Wilson." Wilson's ground-breaking American Ornithology all but vanished beneath Audubon's colorful dust. One engraver on seeing Audubon's a wild turkey commented "that he could engrave better with a pitchfork!" Here is Wilson's wild turkey engraving. You be the judge.