Michael May's Blog, page 163

April 14, 2014

Kill All Monsters at Barnes and Noble

The good folks at Barnes & Noble would like for you to know that Kill All Monsters, Volume 1 and other Alterna comics are now available at their stores and website. They weren't for a while, but that's changed. Always good to have another place to buy, so thanks, Barnes & Noble!

Published on April 14, 2014 16:00

April 7, 2014

Noah (2014)

Noah is my first Darren Aronofsky film. It would’ve been The Wolverine if it had worked out for him to direct that, but it didn’t, which is too bad. As much as I enjoyed the first three quarters of James Mangold’s film, based on Noah, I really want to see what Aronofsky would’ve done with that. It’s not that I’ve intentionally been ignoring the guy, it’s just that none of his films have grabbed me enough on a conceptual level to get me to sit down with one. That changed with Noah.

I expect it’s a lot of people’s first Aronofsky film. It’s based on one of the oldest, most familiar stories in the world and whatever differences folks have about how true it is, everyone knows the basic plot. And based on the $100 million it’s made so far worldwide, they’re also curious to see how Aronofsky’s interpreted it.

That’s what got me into the theater. The story of Noah is a tough one to navigate, even for serious Christians. I had no problem accepting a literal interpretation as a kid, but the older I got, the more I struggled with it. Not just with questions about the logistics of fitting all of those animals into that boat, but also with the theological questions the story raises about the nature of God. I’ve had to wrestle with that stuff, so I was interested in seeing what conclusions Aronofsky came to about it as well.

Like with any movie remake or adaptation, I was far less interested in faithfulness to the source material than I was in the filmmaker’s interpretation of it, so I didn’t approach Noah either as an Aronofsky fan or as a Noah fan and I think that served me well. Most of the criticisms I heard were that either a) it’s not as good as Aronofsky's other work, or b) that it takes a lot of liberties with the story.

I can’t speak to a), but I don’t have any reason to doubt those people. It’s very possible that Pi, Requiem for a Dream, The Fountain, The Wrestler, and Black Swan are each superior to Noah. I just don’t think that’s necessarily relevant to judging it, because none of these movies are competing with each other. It’s perfectly fair to say that The Fountain did this or that better than Noah did as a way of discussing Noah’s specific flaws, but it’s not reasonable to suggest that Noah is worthless simply because it’s not as good as Aronofsky’s previous stuff.

As for b), I’m all for films taking liberties with source material as long as they do it in interesting ways. If I want a faithful account of the Biblical version of Noah’s story, I can turn to Genesis 6. What I was looking for in the film were which themes Aronofsky wanted to highlight and what he would say about them. The movie deeply rewards that approach.

One major theme is humanity’s relationship to our environment. There’s much discussion in the film about our role in creation, with Noah (Russell Crowe) and his family playing the part of vegetarian caretakers while the villainous Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone) insists on his right to subdue the earth and rule over its creatures as harshly as he chooses. The juxtaposition between those views came really close to making me a vegetarian and certainly reinforced my desire to buy meat from humane producers.

It reminds me of something the apostle Paul wrote to the church in Rome: “Everything that God made is waiting with excitement for the time when he will show the world who his children are. The whole world wants very much for that to happen. Everything God made was allowed to become like something that cannot fulfill its purpose. That was not its choice, but God made it happen with this hope in view: That the creation would be made free from ruin—that everything God made would have the same freedom and glory that belong to God’s children. We know that everything God made has been waiting until now in pain like a woman ready to give birth to a child.” (Romans 8:19-22; Easy-to-Read Version)

What he’s saying is that humanity hasn’t just screwed itself up; it’s also screwed up the rest of the world. And when humanity starts acting like God’s children, the rest of creation will breath a huge sigh of relief, because we’ll start behaving towards creation in the way we were meant to. Tubal-cain had a very violent interpretation of what it means to subdue and rule over the earth. Paul and Aronofsky both argue that that’s the wrong way to look at it. Whether you believe in God or not (Paul clearly did; my understanding is that Aronofsky doesn’t), the point is that humans have responsibility for the earth; we’re not here to – as Tubal-cain claims – simply take what’s ours. That message is strong in Noah. As is the message that Tubal-cain isn’t alone in misunderstanding God.

To be fair, God is presented as almost completely unreadable in Noah. The film depicts a world in which the Creator unquestionably exists, but it’s impossible to perfectly understand his will. Noah receives visions, not direct communication, and it’s up to him to interpret them to the best of his ability. How he does that is spoiler territory, so I’ll put the next bit under a…

SPOILER WARNING. If you don’t want to know how the last half of the movie plays out, skip to the END OF SPOILERS note below.

The most fascinating thing about the movie is the way Noah interprets the task God’s given him. As Noah looks at Tubal-cain and the rest of humanity, even as he looks at himself and his own family, he realizes how far humans have fallen and he gives up. After a particularly harrowing visit to Tubal-cain’s village, Noah tells his wife (Jennifer Connelly) that they’re going to finish the task of building the ark, but they aren’t going to get on it when it’s done. Noah believes that God intends for him and his family to die along with everyone else.

Things don’t go according to his plan in a couple of important ways. As the rains come, Tubal-cain attacks and Noah is too distracted fighting the bad guys away from the ark to prevent his own family from getting on it. He then modifies his plan, expecting that his family will simply die of old age without reproducing, and that humanity will still be wiped out and possession of the world will return to the animals without our corrupting presence.

He’s so sure that this is God’s will that when his previously barren daughter-in-law Ila (Emma Watson) becomes miraculously pregnant, Noah is convinced that his duty is to kill the child if it’s a girl, because she’d be capable of mating with one of Noah’s other sons (i.e. her uncles) to continue the species. Leaving aside how gross that is, it’s a fascinating, potent warning about being certain when interpreting God’s will. Noah is alone in his conviction, but no less sure because of that. He’s willing to murder a baby and lose the love of his family because of his confidence that he’s doing what God wants.

As it turns out, Ila has twin daughters and in the film’s most powerful scene Noah can’t bring himself to kill them. Ila explicitly points out later that he chose mercy and suggests that perhaps that was God’s will all along. Noah does some heinous things in the movie and he’s right that at the end of the day he wasn’t any better than the people who died in the flood, and was actually worse than many of them. That he was acting for what he believed were holy reasons doesn’t change what he did. God’s sparing him was an act of mercy. And while unintentional, the mercy that Noah in turn showed his granddaughters was perhaps his greatest, most perfect representation of God’s nature.

END OF SPOILERS

This is profound stuff and the film presents it in a powerful way without handing over all the answers. It leaves a lot to think about, including the nature of a God who would wipe out innocent people in an enormous flood. The film doesn’t sidestep these issues; it raises them and then leaves viewers to wrestle with them on their own, which I think is a good thing. Days after I saw it, I’m still enjoying the process of thinking it through.

As much as I enjoyed Noah, my pleasure in it is based on my interest in this specific source material, so I don’t expect to rush out and immediately start devouring more Aronofsky films. But I’ve been casually curious about The Fountain for a while now because of Hugh Jackman, so I’ll likely bump that up higher in the queue as a result of seeing this. I’m curious though: if you’re an Aronofsky fan, which of his films do you recommend that I follow up Noah with? And of course, whether you’re an Aronofsky fan or not, I’m interested in hearing your thoughts on Noah and the things Aronofsky’s saying in it.

Published on April 07, 2014 04:00

April 3, 2014

Everything you need to know about Beasts of Burden in two panels

Published on April 03, 2014 04:00

April 2, 2014

Everyone Hates Cephalopods: The Video!

Adventureblog reader Dave Mable made this awesome montage of many of the Everyone Hates Cephalopods images I've posted over the years. And put them with the perfect song. Thanks, Dave!

I haven't posted a lot of cephalopod art here lately, but that's mostly because there are other platforms better suited to that kind of thing. I've got a whole Everyone Hates Cephalopods page on Pinterest, and that theme occasionally creeps up on my Tumblr as well. If you haven't checked out either of those yet, I encourage you to do so, especially the Tumblr. I've been very active on that lately and it's full of awesomeness.

Published on April 02, 2014 04:00

April 1, 2014

This is my Boomstick (Award)

A million thanks to Italian book blog Tutto Benenella Mia Testa for not only picking me to receive a Boomstick Award, but also saying very nice and encouraging things about me in the process. It couldn't come at a better time, because frankly I've been overwhelmed with work and life since about last Fall and it's been especially tough the last couple of months to balance this blog with everything else. I never intended for sporadic reviews of James Bond novels to be the only content here, but it's worked out that way lately and that makes me sad. TBMT, on the other hand, makes me happy.

A million thanks to Italian book blog Tutto Benenella Mia Testa for not only picking me to receive a Boomstick Award, but also saying very nice and encouraging things about me in the process. It couldn't come at a better time, because frankly I've been overwhelmed with work and life since about last Fall and it's been especially tough the last couple of months to balance this blog with everything else. I never intended for sporadic reviews of James Bond novels to be the only content here, but it's worked out that way lately and that makes me sad. TBMT, on the other hand, makes me happy.I also got another encouraging note recently from a different person - I'll share that tomorrow - so it's been a nice week and I'm going to use that encouragement to motivate me to post more often. Thanks for being patient.

Published on April 01, 2014 04:00

March 31, 2014

Moonraker by Ian Fleming, Chapters 1-12

For better or worse, Moonraker is a lot different from the first two Bond novels. That's apparent not just from the first few chapters, but also from the way Fleming divides the story into three parts that cover a traditional work week. Part One is called "Monday," Part Two is "Tuesday, Wednesday," and Part Three is "Thursday, Friday."

For better or worse, Moonraker is a lot different from the first two Bond novels. That's apparent not just from the first few chapters, but also from the way Fleming divides the story into three parts that cover a traditional work week. Part One is called "Monday," Part Two is "Tuesday, Wednesday," and Part Three is "Thursday, Friday."The plot is more than just following Bond through a typical week, but you can't tell it from the first couple of chapters. Rather than repeating the cold open technique of the first two novels, Fleming begins Moonraker at the Secret Service shooting range where he reveals that Bond is the best shot in the organization. It's a cool, gadgety range with targets that use beams of light to shoot back at the firer, but Fleming is intentionally mundane in his description. This is routine activity for Bond on a Monday morning.

The first chapter continues the theme of routine. The name of the chapter is "Secret Paper-Work" and that pretty accurately describes the level of action. After the range, Bond heads up to the office he shares with the other two Double-O agents and a secretary named Loelia Ponsonby whom Bond insists on calling "Lil." Fleming explains that all of the Double-Os have hit on her at some point, but have also all been shot down.

It's interesting and cool that Fleming fleshes Ponsonby out more in a few paragraphs than he did Solitaire in all of Live and Let Die. I felt like I got to know her well and I like her dedication to her job despite the serious sexism she encounters there. Fleming doesn't pull any punches describing it either and he shows a lot more awareness that it's a problem than he did about racism or ageism in Live and Let Die. "It was true," he writes, "that an appointment in the Secret Service was a form of peonage. If you were a woman there wasn't much of you left for other relationships. It was easier for the men. They had an excuse for fragmentary affairs. For them marriage and children and a home were out of the question if they were to be of any use 'in the field' as it was cosily termed. But, for the women, an affair outside the Service automatically made you a 'security risk' and in the last analysis you had a choice of resignation from the Service and a normal life, or of perpetual concubinage to your King and Country."

Moonraker gets some criticism for being so mundane, but I love this stuff. Fleming spends a lot of time on the details of Bond's daily life and I find it fascinating. There are only three Double-Os at the moment; Bond has been around the longest and other two (both on assignment at the moment) are 008 and 0011. 008's first name is Bill.

Moonraker gets some criticism for being so mundane, but I love this stuff. Fleming spends a lot of time on the details of Bond's daily life and I find it fascinating. There are only three Double-Os at the moment; Bond has been around the longest and other two (both on assignment at the moment) are 008 and 0011. 008's first name is Bill.Bond goes on two to three missions a year and spends the rest of his time keeping flexible office hours (10:00 to 6:00 being his usual time), doing paperwork and keeping up on developments in intelligence. After hours, he spends his time playing cards with friends and having affairs with married women (kudos to the movie Casino Royale for exploring the psychology behind that detail). Weekends are for golf. Fleming also describes Bond's salary, vacation time, and the small flat he keeps that's maintained by an elderly, Scottish housekeeper named May.

Statutory retirement from the Double-O section is 45, after which he gets a desk job at headquarters. As Bond thinks about this and the number of missions he can expect to go on before reaching it, easy math reveals that he's 37 years old at the time of Moonraker. The mere fact that Bond spends time thinking about this on a routine day follows up something that Fleming has been writing about since Casino Royale: Bond deeply feels his mortality. That's especially true on missions as seen in the first two books, but it's even true as he's doing paperwork in his office. This is a dark character.

Though Moonraker is an atypical book, it's not just about Bond's day-to-day life. At the end of the first chapter, he gets a call from M's office and goes up one floor to the 9th and top story of the Service's office building. Fleming throws in a couple of more details before the plot gets underway, like how Universal Export is more than just the telephone trick revealed in Live and Let Die. It's one of five fake tenants of the building, the others being a radio repair company, the building's management office, and a couple of companies with generic-sounding names like Delaney Brothers and The Omnium Corporation. A retired secretary sits in the management office "politely brushing off salesmen and people who wanted to export something or have their radios mended."

Though Moonraker is an atypical book, it's not just about Bond's day-to-day life. At the end of the first chapter, he gets a call from M's office and goes up one floor to the 9th and top story of the Service's office building. Fleming throws in a couple of more details before the plot gets underway, like how Universal Export is more than just the telephone trick revealed in Live and Let Die. It's one of five fake tenants of the building, the others being a radio repair company, the building's management office, and a couple of companies with generic-sounding names like Delaney Brothers and The Omnium Corporation. A retired secretary sits in the management office "politely brushing off salesmen and people who wanted to export something or have their radios mended."In M's office, we get a little more than we have before of Bond's relationship with Moneypenny. Fleming says that they like each other, that Bond thinks she's attractive, and that she knows he does. There's no banter though. Bond calls her Penny, so apparently he has a thing for giving nicknames to secretaries, but Moneypenny and Loelia Ponsonby apparently talk on a regular basis and the implication is that M's secretary has made herself as off-limits to agents as Bond's has.

As it turns out, M doesn't have a real mission for Bond, but a personal favor to ask. M calls Bond by his first name, which is rare (it's usually 007 when talking about work), and is embarrassed about using Bond for unofficial reasons. I get the feeling that M sees it sort of like stealing pens from work.

But while unofficial, M's problem could have serious consequences if it's not dealt with tactfully and decisively. It involves a man named Hugo Drax, a millionaire hero of England who's spending his own fortune to develop a nuclear missile - the Moonraker - for England that's capable of reaching any country in the world. Unfortunately, Drax cheats at cards and it's only a matter of time before someone at his club (which is also M's club, you see the connection) notices and creates a scandal that could offend Drax enough to jeopardize the Moonraker project. The chairman at Blades knows that M is somehow connected to British Intelligence and has asked him to help, so M naturally thought of the Service's best card player (as well as the hero of Casino Royale) as a possible solution. Bond, who has a ton of respect for M, agrees. He'll play against Drax and without creating a scandal, beat the man at his own game. Hopefully that will be enough to let Drax know that people are onto him and cause him to play straight in the future.

But while unofficial, M's problem could have serious consequences if it's not dealt with tactfully and decisively. It involves a man named Hugo Drax, a millionaire hero of England who's spending his own fortune to develop a nuclear missile - the Moonraker - for England that's capable of reaching any country in the world. Unfortunately, Drax cheats at cards and it's only a matter of time before someone at his club (which is also M's club, you see the connection) notices and creates a scandal that could offend Drax enough to jeopardize the Moonraker project. The chairman at Blades knows that M is somehow connected to British Intelligence and has asked him to help, so M naturally thought of the Service's best card player (as well as the hero of Casino Royale) as a possible solution. Bond, who has a ton of respect for M, agrees. He'll play against Drax and without creating a scandal, beat the man at his own game. Hopefully that will be enough to let Drax know that people are onto him and cause him to play straight in the future.Though Fleming's given the first taste of the plot, things slow down again when Bond arrives at Blades. There's a lot of history about the place and Fleming immerses the reader in details about the club and what it would be like to eat and play there. He also reveals that M's first name is Miles and that his last name also starts with M. None of this is boring to me though, and I got a kick out of watching Bond and M hang out, especially as I imagined them being played by Daniel Craig and Bernard Lee. I have a hard time dream-casting the literary Bond, but M is easy. The movies got it right the first time and Bernard Lee was the perfect representation of the character as Fleming wrote him.

Eventually, the card game begins and though Fleming uses a lot of jargon and is much less clear about the rules of bridge than he was about baccarat in Casino Royale, he also makes it easy to tell who's doing well and who isn't. The stakes of the game aren't as high as they were in Casino Royale, but Fleming keeps it interesting by making Drax an obnoxious jerk that needs taking down. He infuriates Bond and - more importantly - he infuriated me. It's a tense, well-written scene and made me realize that I would have loved a Fleming anthology of nothing but stories about people playing cards. He's able to pull so much drama out of that setting.

Of course Bond succeeds in his goal and if he's made a powerful enemy in the process, he doesn't seem to care. The chances of Bond's running into Drax in the future are almost none. Except of course that this is fiction and chance has nothing to do with it. The next morning, Bond is called to M's office again, because there's been a murder at Drax's plant.

Of course Bond succeeds in his goal and if he's made a powerful enemy in the process, he doesn't seem to care. The chances of Bond's running into Drax in the future are almost none. Except of course that this is fiction and chance has nothing to do with it. The next morning, Bond is called to M's office again, because there's been a murder at Drax's plant.Ordinarily that would be outside of the Service's jurisdiction, but a technicality lets them get involved. Drax employs a lot of German expatriates in his plant and it was one of them who committed the murder in a tavern and then immediately killed himself. Since it was the Secret Service who cleared the German staff, M has enough room to wiggle into the case, but he admits to Bond that he probably wouldn't have bothered had it not been for the experience with Drax at Blades. Bond agrees that it's intriguing and takes the assignment.

Bond expects his second meeting with Drax to be awkward, but resolves for himself to let bygones be bygones and to keep an open mind about Drax's innocence in the affair. Fortunately, Drax also seems willing to bury the hatchet and welcomes Bond to his team as the new head of security, replacing the murdered man. Drax is much more friendly in his own home where he controls everything and Bond quickly not only forgives Drax, but remembers why he always admired the industrialist before yesterday.

On site, Bond also meets the other members of Drax's staff including a couple of charmingly cartoonish caricatures of mad scientists (one of whom Fleming explicitly compares to Peter Lorre) and Scotland Yard agent Gala Brand. Brand has been undercover for a while as Drax's personal assistant, but she's also involved in the case as the motive for the murder. The killer was apparently in love with her, but resented her close relationship with the victim.

On site, Bond also meets the other members of Drax's staff including a couple of charmingly cartoonish caricatures of mad scientists (one of whom Fleming explicitly compares to Peter Lorre) and Scotland Yard agent Gala Brand. Brand has been undercover for a while as Drax's personal assistant, but she's also involved in the case as the motive for the murder. The killer was apparently in love with her, but resented her close relationship with the victim.When she meets Bond, Brand is very cold to him. The reason for that is as much a mystery as everything else, but just as interesting is Bond's reaction to it. He was initially impressed with her professionalism, but when he realizes she actively dislikes him, he doesn't just take it personally; he also loses respect for her capability as an agent. He's kind of a baby about it and once he starts thinking of her in terms of whether she likes him or not, it's like he can't think of her as a colleague anymore. As his attraction to her increases, his professional regard for her decreases, and he's clearly attracted to her. She's totally his type: brunette and without ostentation. She wears no makeup, little jewelry, and uses natural nail polish. Just like Vesper and Solitaire.

As Tuesday evening winds down and the book reaches its halfway point, Moonraker has a lot of promise. Getting to know Bond better in the first half was great, but now he's in a tense situation with a powerful, possibly dangerous man and questions about the German killer and what role Brand played in the murder. It's almost like an English country mystery with a science fiction subplot and some international intrigue as extra flavor. I feel like we're in good shape heading into the second half.

Published on March 31, 2014 04:00

March 17, 2014

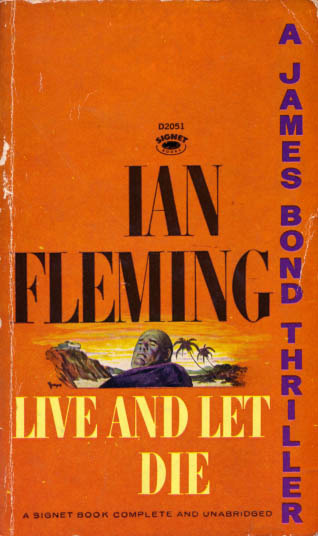

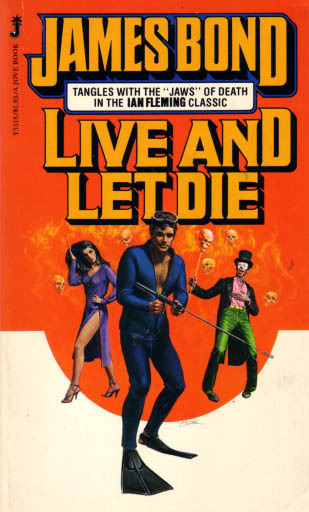

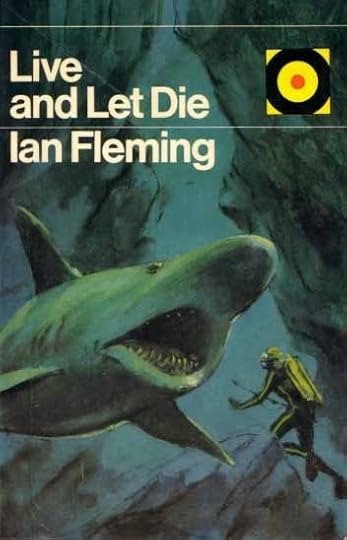

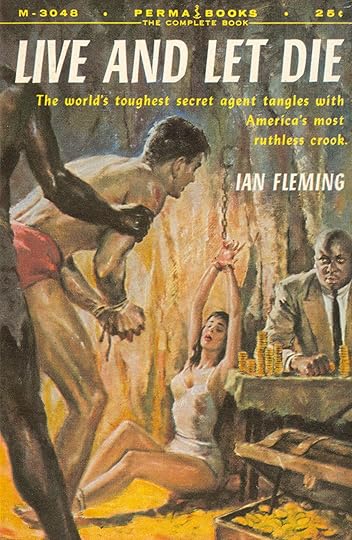

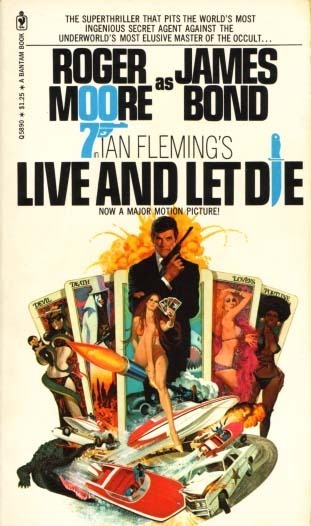

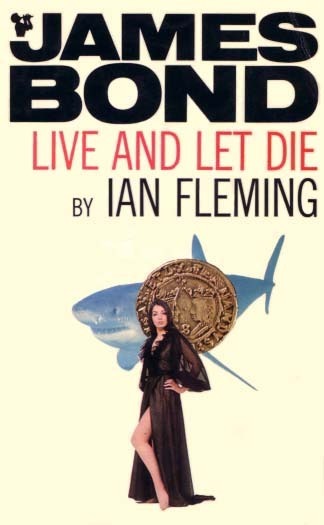

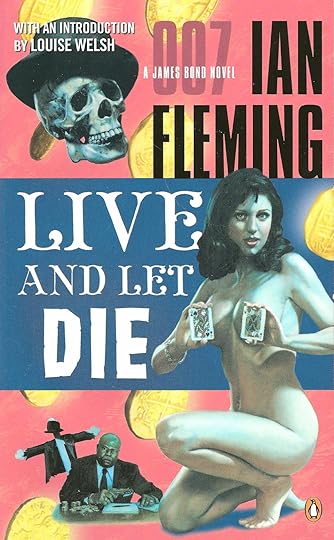

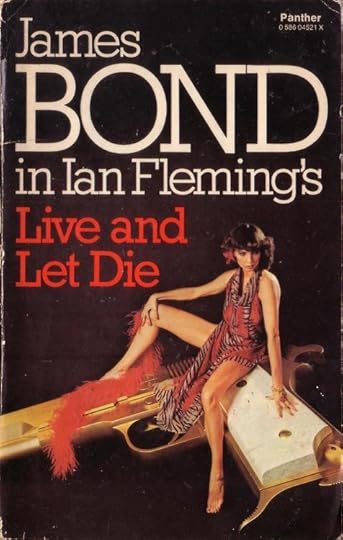

Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming, Chapters 11 - 23

I covered the first half of Live and Let Die a couple of weeks ago. Since this post wraps up the novel, I'll be spoiling some things about the ending.

I covered the first half of Live and Let Die a couple of weeks ago. Since this post wraps up the novel, I'll be spoiling some things about the ending.As Bond and Solitaire make their way by train to Florida to see where Mr. Big is bringing his pirate treasure into the country, the couple begins to flirt, but agree not to have sex yet. For one thing, Bond's hand is still bothering him where Tee Hee broke his little finger and the spy doesn't feel like he can work his moves properly one-handed. Beside that, they suspect that Big has people on the train wanting to kill them, so they're not too keen on getting naked and making themselves vulnerable. They also have to get up early, because Bond wants to sneak off the train in Jacksonville instead of riding it all the way to St. Petersburg/Tampa as planned. Lots of excuses.

The couple is obviously into each other though and pretty much promise to do it as soon as they get the chance. Bond is attracted to Solitaire - she's an aggressive kisser and seems to be a strong, confident woman - and she believes he's the strong man she's been waiting for. Sadly, that's not just about helping her escape Big, but I'll have more to say about that in a minute.

Bond stays very friendly with Solitaire, but it's worth pointing out that he still doesn't seem to entirely trust her. He asks her lots of questions about Big's organization, but he never offers her any information or confides in her about his mission. Like I mentioned in the first half of the novel, Bond's relationship with Solitaire is absolutely not a repeat of what he went through with Vesper. He's having a fun time getting to know Solitaire and seems at ease around her, but he's not letting her in. That's important to the long-term arc of Bond's character throughout the series. He got burned badly in Casino Royale and though Fleming isn't explicit about saying it, Bond's not letting that happen again in Live and Let Die.

In Florida, the novel adds agism to it's already rampant racism. Bond, Solitaire, and Leiter (whom they meet up with again in St. Petersburg) constantly refer to the "oldsters" and "baldheads" in Florida and how gross they are. Vesper calls the area, "The Great American Graveyard" and warns Bond that "it's a terrifying sight, all these old people with their spectacles and hearing-aids and clicking false teeth." When Bond finally gets to see it for himself, he's horrified and Leiter agrees that "it makes you want to climb right into the tomb and pull the lid down." Fleming had a gift for prose, but it's as poorly put to use in this case as it is when he's writing about black people.

It's also in St. Petersburg that Solitaire loses all the strength and confidence she showed when Bond first met her in Big's office. One of the things I'm going to write about when we get to the movies is the moment in most of the films where the girl gets dumb. Many a Bond girl starts the movie capable and smart, but turns into a puddle of "Oh, James" goo by the end. Unfortunately, there's a literary precedent for that with Solitaire. She's quietly defiant in Big's office, but as soon as she gets near his operation in St. Petersburg, she grows frightened and clingy.

To be fair, that might be her telepathy/precognition at work. She tells Bond that she has a feeling, but can't articulate what it is. And sure enough, something awful happens in St. Petersburg. But her change to scared rabbit is so quick that it's jarring.

As I said though, she has reason to be worried. When Bond and Leiter check out the warehouse where Big's men have been bringing in the pirate loot from Jamaica, it lets Big's operation know where the good guys are. Solitaire is kidnapped and Leiter is captured and fed to a shark at the warehouse. That part is familiar to movie fans because it got used in Licence to Kill, as did Bond's breaking into the warehouse to take his revenge.

As I said though, she has reason to be worried. When Bond and Leiter check out the warehouse where Big's men have been bringing in the pirate loot from Jamaica, it lets Big's operation know where the good guys are. Solitaire is kidnapped and Leiter is captured and fed to a shark at the warehouse. That part is familiar to movie fans because it got used in Licence to Kill, as did Bond's breaking into the warehouse to take his revenge. What happens to Leiter is especially worrying and heartbreaking. As we noticed in the first half of the book, Leiter's charm and humor has a positive effect on Bond's dark outlook about his job and the world in general. Leiter is Robin to Bond's Batman. But that makes Live and Let Die sort of Bond's Death in the Family . Though like in Licence to Kill Leiter doesn't die, he's severely maimed and it's not certain he's going to make it. It doesn't propel Bond through the rest of the story the way it does in Licence to Kill, but it certainly ups the stakes for him and makes Big feel even more ruthless. But more on that shortly.

In Licence to Kill, the bad guys are smuggling drugs in tanks full of maggots, but in the novel Live and Let Die, it's pirate gold in the bottom of tanks holding poisonous fish. Feeling like he knows everything he needs to about Big's stateside operation (and feeling unwelcome in the US by the FBI thanks to all the killing he's been doing), Bond catches a flight for Jamaica and the last stage of his operation. Felix's injuries and Big's deadliness are weighing on Bond though and he feels as down and fallible as he did at the end of Casino Royale. During some bad turbulence over Cuba, Bond's even sure that his plane is going down, fantasizing that the mechanic who checked it out was distracted by a bad romance and that Bond's going to pay for it with his life. It's a beautifully written passage, as is the part where the plane stabilizes and Bond's mood improves. Fleming knew something about mood swings and the literary Bond is a far cry from the films' usual portrayal of a confident, swaggering spy. This isn't the last time Bond goes through this shift in Live and Let Die either.

In Jamaica, he's helped out by the eye-patched Strangways, the British Secret Service's chief agent in the Caribbean. Fans of the film Dr. No will recognize Strangways' name as the agent whose death in the beginning of that movie brings Bond to Jamaica and sets the plot in motion. Here, he sort of takes Leiter's place as the guy who lightens Bond's mood. He's not as charming as Leiter, but he's smart and pleasant and he also introduces Bond to the indispensable Quarrel, someone else familiar to Dr. No viewers.

In Jamaica, he's helped out by the eye-patched Strangways, the British Secret Service's chief agent in the Caribbean. Fans of the film Dr. No will recognize Strangways' name as the agent whose death in the beginning of that movie brings Bond to Jamaica and sets the plot in motion. Here, he sort of takes Leiter's place as the guy who lightens Bond's mood. He's not as charming as Leiter, but he's smart and pleasant and he also introduces Bond to the indispensable Quarrel, someone else familiar to Dr. No viewers.Surprisingly, Fleming communicates a great deal of affection from Bond for Quarrel. Bond has liked individual black characters earlier in the novel, but he positively gushes about Quarrel and Fleming defines their relationship as "a Scots laird with his head stalker; authority was unspoken and there was no room for servility." It's obviously not a relationship between equals, but it's the most progressive relationship between a white person and a black person that Fleming offers.

No, wait, that's not true. Big is absolutely presented as Bond's equal. The villain is a worthy follow-up to Casino Royale's Le Chiffre. He's every bit as ruthless, but even more deadly and smart. Le Chiffre was ultimately brought down because of his vices for women and gambling, but Big has no obvious weaknesses. He's ultimately brought down through good intelligence and Bond's planning, but not easily.

That's why Bond frets so much during the case and needs people like Leiter and Strangways to keep him from sinking into depression. He has Quarrel get him into physical condition and train him in diving techniques so that he can swim through shark- and barracuda-filled waters to Big's private island (and the source of the pirate treasure that's financing SMERSH), but Bond easily loses confidence despite this preparation. Fleming writes that "He, Bond, after a week's paddling with his nanny beside him in the sunshine, was going out tonight, in a few hours, to walk alone under that black sheet of water. It was crazy, unthinkable."

That's why Bond frets so much during the case and needs people like Leiter and Strangways to keep him from sinking into depression. He has Quarrel get him into physical condition and train him in diving techniques so that he can swim through shark- and barracuda-filled waters to Big's private island (and the source of the pirate treasure that's financing SMERSH), but Bond easily loses confidence despite this preparation. Fleming writes that "He, Bond, after a week's paddling with his nanny beside him in the sunshine, was going out tonight, in a few hours, to walk alone under that black sheet of water. It was crazy, unthinkable."What's lovely though is that Fleming allows Bond to pull himself heroically out of his own despair. As the time for the dive draws closer, "Bond was immersed in a sea of practical details and the shadow of fear had fled back to the dark pools under the palm trees." This struggle between confidence and self-doubt is what makes the literary Bond such a compelling character. He has his own demons to conquer in addition to horrible villains and it's exciting to see him rise to the challenge. The classic, cinematic Bond is an aspirational character; Fleming's version is far more relatable.

In preparation for his swim, Bond orders some equipment from Q Branch, but like in Casino Royale, the Secret Service's quartermaster division provides not fantastical gadgets, but mundane supplies. In this case it's SCUBA gear, underwater flashlights, and weapons no more esoteric than a commando knife, harpoon gun, and Limpet mine.

Fleming also writes a lot about Jamaica, including the geography of the island and Bond's own history with it. Fleming famously owned a house called Goldeneye there and vacationed there every year where he would write his novels. So he gave Bond some connection with the place too, saying that Bond was stationed there after WWII "when the Communist headquarters in Cuba was trying to infiltrate the Jamaican labour unions." Bond had fallen in love with the place as explained in Casino Royale when he chose as his cover to play the part of a wealthy Englishmen from there.

Fleming also writes a lot about Jamaica, including the geography of the island and Bond's own history with it. Fleming famously owned a house called Goldeneye there and vacationed there every year where he would write his novels. So he gave Bond some connection with the place too, saying that Bond was stationed there after WWII "when the Communist headquarters in Cuba was trying to infiltrate the Jamaican labour unions." Bond had fallen in love with the place as explained in Casino Royale when he chose as his cover to play the part of a wealthy Englishmen from there.Unfortunately for Bond, his underwater journey to Big's island is eventful and features a cool fight with an octopus that gives away Bond's presence and leads to his capture. The cinematic Bond takes a lot of grief for not being a good spy, and rightfully so. I'll have more to say about this when we get to the movies, but there's a reason that Judi Dench's M takes to referring to him as a "blunt instrument." He's a useful tool so long as what she wants to do is throw him into a situation and see what he's able to shake up. One of his most reliable techniques is to get himself caught by the villain and then proceed to destroy the bad guy's operation from the inside.

I say all that to say that that's not what happens in this book. Bond is captured, but the success of his mission doesn't depend on that. By the time Big takes him in, Bond's already attached his Limpet mine to Big's boat. Big's operation is going to be destroyed and Big will probably die in the process; the question is whether Bond and Solitaire (whom he's reunited with in captivity) will die as well.

Big's plan for Bond and Solitaire is far better than the ones the typical, cinematic Bond villains come up with. Unlike the movie version of Live and Let Die, which seems to be the template for Dr. Evil's "unnecessarily slow dipping mechanism" in Austin Powers, the literary Big ties Bond and Solitaire to the back of his boat, intending to drag them across a coral reef until their bleeding bodies attract enough sharks and barracuda to eat them alive. It's such a clever scheme that it got transplanted into the film For Your Eyes Only, though Bond escapes it in a different way there than he does in this book.

Big's plan for Bond and Solitaire is far better than the ones the typical, cinematic Bond villains come up with. Unlike the movie version of Live and Let Die, which seems to be the template for Dr. Evil's "unnecessarily slow dipping mechanism" in Austin Powers, the literary Big ties Bond and Solitaire to the back of his boat, intending to drag them across a coral reef until their bleeding bodies attract enough sharks and barracuda to eat them alive. It's such a clever scheme that it got transplanted into the film For Your Eyes Only, though Bond escapes it in a different way there than he does in this book.Bond's dark side almost gets the better of him again and he decides that if the mine on Big's boat hasn't exploded by the time the sharks are coming, Bond will drown Solitaire under his own body and then use her corpse to weigh down and drown himself. Fortunately, it doesn't come to that. The mine goes off in time and Bond escapes with his "prize."

It's curious to see Bond's attitude about Solitaire change. In the earlier chapters, she's his partner. After St. Petersburg though, she's a prize to be rescued and won. Bond uses that word explicitly when he's thinking about her. She's his reward for defeating Mr. Big, much like Bond thought about Vesper before he fell for her.

Solitaire tells Bond that she loves him shortly before their modified keelhauling and he returns the sentiment, but there's no evidence that he's serious about it. He tells her in the same breath that he thinks they can survive, even while he's contemplating killing her and himself to keep from being eaten alive. In other words, he a lying liar just trying to keep her calm.

Solitaire tells Bond that she loves him shortly before their modified keelhauling and he returns the sentiment, but there's no evidence that he's serious about it. He tells her in the same breath that he thinks they can survive, even while he's contemplating killing her and himself to keep from being eaten alive. In other words, he a lying liar just trying to keep her calm.Solitaire is gorgeous, but she's too needy and volatile to be reliable in a relationship. She changed personalities in St. Petersburg and as a result his interest in her never progresses beyond the concept of prize. I suspect that's going to be an important concept going forward in the series and it'll be interesting to see which women - if any - are able to rise above that in Bond's mine. Vesper never would have if Bond hadn't been tortured and made so vulnerable, and his letting her become more than a prize had disastrous emotional consequences for him.

So we leave Bond and Solitaire, recuperating on a beach in Jamaica, wondering if Bond will ever find love or real human connection again. He desperately needs it to help encourage him through his darkest moments, but he's not yet finding it in a woman and even his relationships with guys like Leiter, Strangways, and Quarrel - while somewhat effective against the darkness - are superficial and temporary.

That's the curse of Bond's job, but it's also that disconnection from humanity that makes him such a useful sociopath in hunting down and destroying evil people like Mr. Big. Do we want him to find happiness? Or do we need him up on that wall, protecting us?

Published on March 17, 2014 04:00

February 24, 2014

Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming, Chapters 1 - 10

As I mentioned in my intro to this project, I'm a slow reader. I'd like to have a Bond post up each week though, so I'm going to write about however much of the books I've read in the last seven days. Hopefully, that'll also help control the length of some of these posts, because I do tend to ramble.

As I mentioned in my intro to this project, I'm a slow reader. I'd like to have a Bond post up each week though, so I'm going to write about however much of the books I've read in the last seven days. Hopefully, that'll also help control the length of some of these posts, because I do tend to ramble.Before Casino Royale was even published, Ian Fleming had completed his second Bond novel. Inspired in part by the train ride that Fleming and his wife took from New York to Florida before heading to Jamaica where he wrote the book, Live and Let Die has Bond making the same trip as he investigates a criminal named Mr. Big.

Like Casino Royale, Live and Let Die begins with a cold open as Bond arrives in New York City to collaborate with the CIA and FBI, then flashes back to the briefings that sent him there. Bond has mostly recovered from the events of Casino Royale, but still carries emotional scars. How much damage he took from Vesper's betrayal remains to be seen, but at the very least he's passionately bent on taking down SMERSH, the Soviet organization behind most of the troubles in Casino Royale. M knows this, so when a possible SMERSH agent is identified in the United States, M gives Bond the job of verifying the intelligence and - if necessary - eliminating the threat.

The connection between Mr. Big and SMERSH is circumstantial. The British have reason to believe that SMERSH is financed partially by a horde of pirate loot that once belonged to Captain Morgan, and Big has been caught handling some of that treasure. On paper, part of Bond's job is making sure that Big is actually involved with the Soviets, but that fact is mostly taken for granted. Bond is after Big from the get-go.

Before getting into the mission, there are a couple of things worth noting from the briefing scene. First, Fleming reveals that Bond was stationed in the United States during World War II, so this isn't his first trip to the country. Also, this scene is the first interaction Fleming's written between Bond and Moneypenny. It's a tiny bit - nothing more than an encouraging smile from her - but does establish that they're on friendly terms, even if they're not openly flirtatious (yet?).

Before getting into the mission, there are a couple of things worth noting from the briefing scene. First, Fleming reveals that Bond was stationed in the United States during World War II, so this isn't his first trip to the country. Also, this scene is the first interaction Fleming's written between Bond and Moneypenny. It's a tiny bit - nothing more than an encouraging smile from her - but does establish that they're on friendly terms, even if they're not openly flirtatious (yet?).It's also in the briefing that the extremely offensive racism of Live and Let Die first appears. I'm not going to keep bringing it up after this paragraph, but it can't be ignored either. As M and Bond discuss black people, they make all sorts of gross generalizations about the entire race and talk about them as if they're some sort of alien species. They make it sound like Mr. Big has turned the entire black population of the United States into a spy network, as if that's possible simply because they're all the same race. Fleming uses especially crude metaphors to describe them, like having them in a club "packed like black olives in a jar." The N-Word also comes up a lot all through the book; in casual conversation as well as in a chapter title. This is 1954, so Product of the Times and all that, but racism saturates the book to an extent that enjoying it may be impossible for many people. My approach though is to acknowledge it and move on, seeing what positive things can be gleaned from the book.

Mr. Big is of course a ridiculous name, but Fleming makes it work by giving it a specific origin. First of all, it's an acronym for the Haitian's real name, Buonaparte Ignace Gallia. That and Big's stature earned him the nickname even as a boy, and I love that Fleming includes previous versions of it, like Big Boy and The Big Man. It lets me believe that the name evolved naturally and isn't just a parody of an American criminal.

Even though I don't buy the extent of Big's reach as it's imagined by Bond, the villain is still plenty deadly and frightening. We'll talk more about differences between the book and the film when we get to the film, but a major change is that the literary Big doesn't parcel out his identities the way the movie version does. The film's Kananga doesn't exist in the book and Baron Samedi isn't a separate character either. Coming from Haiti, Big has started his own voodoo cult and encourages the belief that he himself is Samedi.

Even though I don't buy the extent of Big's reach as it's imagined by Bond, the villain is still plenty deadly and frightening. We'll talk more about differences between the book and the film when we get to the film, but a major change is that the literary Big doesn't parcel out his identities the way the movie version does. The film's Kananga doesn't exist in the book and Baron Samedi isn't a separate character either. Coming from Haiti, Big has started his own voodoo cult and encourages the belief that he himself is Samedi.Some of Big's other movie henchmen do come right out of the novel though. Whisper is here (a tuberculosis victim with one lung who quietly directs Big's men via a massive switchboard) and so is the giggly Tee Hee (though he has both hands and no claw). Goofy nicknames are apparently standard in Big's gang, because we also get to meet McThing, Blabbermouth Foley, Sam Miami, and The Flannel.

As in the movie, Bond meets up with Felix Leiter in New York and the two of them check out Big's operations in Harlem. Fleming's talent for description really shines here and he gives a nice travelogue of Harlem. It's fun reading Fleming describe the United States. He has Bond dressing in American clothes (including horn-rimmed glasses!) and even tries his hand at American dialogue.

He's not entirely successful at American speech though and Felix sounds like no Texan I've ever met when he says, "One used to go to Harlem just as one goes to Montmartre in Paris. They were glad to take one's money." Fleming also unwisely attempts to write the dialogue of most of the black characters phonetically, which at worst contributes to the overall racism, and at best reminds me of Chris Claremont writing Rogue and Gambit.

Felix and Bond's night out ends much like it does in the movie, with a trick booth in one of Big's clubs (though watching a stripper instead of a lounge singer). The two spies are separated and Bond gets to meet Mr. Big. Like in Casino Royale, it's the villain who gets all the gadgets in Live and Let Die, from the trick booth to Big's desk with a gun built into it. As if to explain these gimmicks, Fleming has Bond ruminate on the gadgets and their function. "They had not been just empty conceits," Fleming writes, "designed to impress. Again, there was nothing absurd about this gun. Rather painstaking, perhaps, but, he had to admit, technically sound." That describes very well Fleming's use of gadgets in the novels so far. Whether it's Le Chiffre's carpet of spiked chainmail or Big's desk-gun, they're sensational, but also functional and possible; not like the silliness the movies would become known for.

Felix and Bond's night out ends much like it does in the movie, with a trick booth in one of Big's clubs (though watching a stripper instead of a lounge singer). The two spies are separated and Bond gets to meet Mr. Big. Like in Casino Royale, it's the villain who gets all the gadgets in Live and Let Die, from the trick booth to Big's desk with a gun built into it. As if to explain these gimmicks, Fleming has Bond ruminate on the gadgets and their function. "They had not been just empty conceits," Fleming writes, "designed to impress. Again, there was nothing absurd about this gun. Rather painstaking, perhaps, but, he had to admit, technically sound." That describes very well Fleming's use of gadgets in the novels so far. Whether it's Le Chiffre's carpet of spiked chainmail or Big's desk-gun, they're sensational, but also functional and possible; not like the silliness the movies would become known for.In Casino Royale, Fleming said that Bond killed two men before receiving his Double-O number, but Big reveals (if his intelligence is reliable) that it only takes one cold-blooded killing in the line of duty to achieve that. He also notes that the number of men who attain that would still be relatively small in an organization like MI-6 that doesn't routinely use assassination as a tool.

Of course, the reason Big wants to meet Bond is to find out how much he knows. He has Bond tied to a chair, which naturally brings to mind the torture scene from Casino Royale. Fleming doesn't repeat himself though, and instead of having Big go to town on Bond with a nearby riding whip, the author introduces Solitaire, who's able to use telepathy to tell if Bond is lying. Not only is it different from torture, it's - as Big says - more reliable.

Solitaire is quite different from the innocent, naive lamb of the movie. Fleming's version is confident and powerful. In the film, Big has fiercely protected Solitaire's virginity so that he can continue using her powers. If Fleming's version is a virgin (the subject doesn't come up right away), it's by her own choosing. She's always avoided men, which is why folks in Haiti started calling her Solitaire (a joke about playing with herself?). Big still controls her, but he has a more difficult time than in the movie and occasionally resorts to physical beatings to keep her obedient, hence the riding whip.

Solitaire is quite different from the innocent, naive lamb of the movie. Fleming's version is confident and powerful. In the film, Big has fiercely protected Solitaire's virginity so that he can continue using her powers. If Fleming's version is a virgin (the subject doesn't come up right away), it's by her own choosing. She's always avoided men, which is why folks in Haiti started calling her Solitaire (a joke about playing with herself?). Big still controls her, but he has a more difficult time than in the movie and occasionally resorts to physical beatings to keep her obedient, hence the riding whip.Another example of the literary Solitaire's increased agency is that she doesn't have to be tricked into helping Bond. The movie Solitaire has been Big's captive her entire life, but Fleming's has only been with the criminal for about a year. She's looking for a way out and sees Bond as it. In a scene that the movie uses later in its story, Solitaire lies to Big. She verifies Bond's cover story, but in the novel, Big doesn't know she's lying. He decides to let Bond go with a nasty beating, starting with having Tee Hee break one of Bond's fingers. The movie uses that later too, but only as a threat. Fleming is much meaner to his Bond than the movie writers are to theirs.

But he's also nicer. If memory serves, Roger Moore only escapes Big's clutches in the early confrontation with outside help . Fleming's Bond has to work hard to escape with just a broken pinky, but his doing so makes him a tougher, more capable hero.

Hilariously, Felix uses a different tactic to get away from the guys holding him. When he and Bond compare notes later, Felix reveals that he made friends with one of his guards by discussing jazz. That's not as racist as it sounds; the other guards don't succumb to Felix's charm, so Felix has simply made a real friend by talking about a common interest. Jazz is something that Felix is legitimately interested in as evidenced by his going on about it to Bond longer than necessary to tell the story. Felix is a nerd for jazz.

The difference in the two spies' escapes highlights something important about Felix. Bond's escape is brutal. Felix's is charming. After they hang up, Bond smiles to himself and reflects that Felix's cheerfulness had "wiped away his exhaustion and his black memories" of his encounter with Big. Casino Royale beat Bond down hard and now he's up against another ruthless villain, but the darkness of Bond's world is made bearable by having guys like Felix (and, in Casino Royale, Mathis) in it. The books need these characters to keep the tone from becoming overly oppressive, but Bond needs them too for the same reason. They're the Robins to his Batman.

The difference in the two spies' escapes highlights something important about Felix. Bond's escape is brutal. Felix's is charming. After they hang up, Bond smiles to himself and reflects that Felix's cheerfulness had "wiped away his exhaustion and his black memories" of his encounter with Big. Casino Royale beat Bond down hard and now he's up against another ruthless villain, but the darkness of Bond's world is made bearable by having guys like Felix (and, in Casino Royale, Mathis) in it. The books need these characters to keep the tone from becoming overly oppressive, but Bond needs them too for the same reason. They're the Robins to his Batman.The result of Bond's meeting with Big is that Bond is no longer welcome in New York City. The FBI is furious that Bond forced a confrontation, so Bond and Felix decide to leave and head for Florida where Big's pirate gold is likely coming in from the Caribbean. As Bond communicates this to M, Fleming introduces the concept of Universal Export, a major element of Bond's world. The films eventually went so far as to have UE plaques on MI-6 buildings, but in Live and Let Die it's simply a cover for agents to use when communicating over unsecure lines.

Before Bond leaves, he gets a call from Solitaire who - still seeing him as her opportunity to escape Big - is desperate to join up with him. Bond doesn't trust her, but knows that she lied for him before and decides to help her despite his misgivings. Once they meet on the train headed to Florida though, they begin to relax around each other. She tells him her real name - Simone Latrelle - and he decides that in addition to her usefulness against Big, he just plain likes her. There's no sign of his falling for her like he did with Vesper, but she's a beautiful, confident woman and he just enjoys her company. There's no immediately hopping into bed a la Roger Moore and every woman he ever met. In fact, as the train leaves New York, Bond and Solitaire have figured out who sleeps in which bunk and there's not even a hint of romance yet.

There is, however, every indication that their movements have not gone unnoticed by Big's spies, some of whom are even on the train...

Published on February 24, 2014 04:00

February 19, 2014

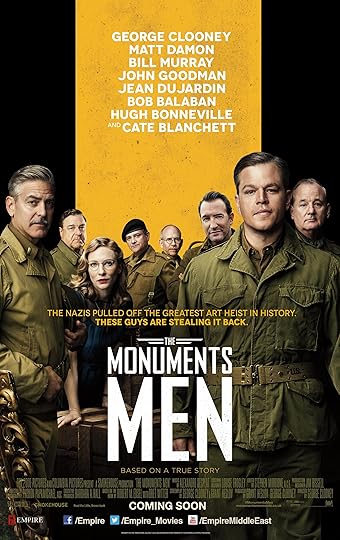

The Monuments Men and the importance of art

My first reaction to The Monuments Men was how sad it is when art about the importance of art largely fails to communicate the importance of art. That’s what I tweeted right after I saw it, but I’d like to unpack that complaint a little more.

The Monuments Men spends a lot of time telling its viewers that art is important. George Clooney’s character assures the people around him (multiple times) that art is what the Allies are really defending against the Nazis. Art, he claims, is the memories of a civilization. An entire generation can be wiped out, but the culture will endure as long as its artifacts do.

His character arc is to discover just how much he thinks this is true. As his team lands in Europe he cautions them to be careful, saying that no piece of art is worth their lives. By the end of the film, he’s changed his mind about that. In a hammy scene, he debriefs FDR who pointedly asks if the mission was worth the loss of life. Clooney’s character proudly declares that yes it was. He’s clearly taken a journey in the film. The trouble is that I didn’t get to take it with him.The film doesn’t offer a compelling reason to care about the pieces that the team is trying to save. For all the talking about why art matters, the movie largely fails to show it in a way that makes an emotional impact. It tries a couple of times though, and it’s enlightening to take a look at those and see what they’re saying. Even if they don’t entirely succeed to support the stated message of the film, on their own they make some thoughtful points about the value of art.

There’s a moment that’s in the trailer when Matt Damon looks around at a room full of paintings and asks Cate Blanchett what all that stuff is. “People’s lives,” she says. In addition to the movie’s awesome cast, that’s the line that got me into the theater. Art is important to the extent that it reflects people’s lives. It’s why we sometimes call it culture. There’s a sense in which art documents the culture – the society; the thoughts and values – of the people who made it. That’s what the movie is trying to say, but for the most part it says it so academically that it’s tough to connect to that idea emotionally. Blanchett’s line helps correct that, but it’s not enough. And it’s undermined by other moments in the movie.

For instance, there’s another scene in which Matt Damon discovers the address where a painting came from and takes it back. Maybe it’s a famous painting, but I didn’t recognize it. More likely – and I actually, deeply hope this is the case – it’s just a portrait of a loved one. He takes it to the abandoned house from which the Nazis stole it and sees the discoloration on the wall where it once hung. As he puts it back, Blanchett comes into the room and says that the people who used to live there probably won’t be coming back. I forget Damon’s exact response, but he basically questions whether or not that matters. Which – in a nutshell – is the problem with the entire movie.

It’s a story about returning art to its proper place (though the definition of proper place is never debated and that could be a fascinating discussion all by itself). But The Monuments Men isn’t all that interested in why this is an important task. For Damon’s character, it’s just about the activity of returning art to the physical location from which it came. Blanchett suggests that it’s about returning it to the people for whom it has meaning. That can be a museum or other cultural center, but the appreciation of a museum patron for a piece is a crucially different thing than the meaning it holds for someone who’s intimately connected to it. The movie is interested enough in that difference to acknowledge it exists, but not enough to spend any time on it for the art that the team is actually tracking down and risking their lives for.

One final scene will help clarify what I’m talking about. It’s Christmastime and Bill Murray’s character gets a phonograph record from home. He doesn’t say what it is at first, just that he wants to hear it, and my first thought was that it was a new recording by a favorite musician. When he listens to it though, it’s revealed to be a recording of his family sending him greetings and then someone (His daughter maybe? The movie probably says, but I missed it.) sings “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

It’s a sweet moment and Murray reveals a lot of longing for home in that scene. But it’s made even more powerful by the juxtaposition of my expectation for the record and what it actually was. I thought it was just going to be a piece of art that he liked the way you like a painting in a museum or a carving in a church. Instead, it was art – specifically, a song – that he was deeply connected to because of the singer and the time of year. George Clooney could have made an entire movie about trying to rescue that record and I would have been more invested in it than I was in the salvation of the classically “important” pieces that are the focus of The Monuments Men.

It needn’t have been that way. Instead of just telling me that the Ghent Altarpiece is hugely important and needs to be saved, the film could have shown me how important it was to a character I cared about. It tries to do this with Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges, but again, it tells me that this character likes that piece without ever convincing me why. And that's the overriding, fatal flaw of the rest of the film, too.

Published on February 19, 2014 04:00

February 17, 2014

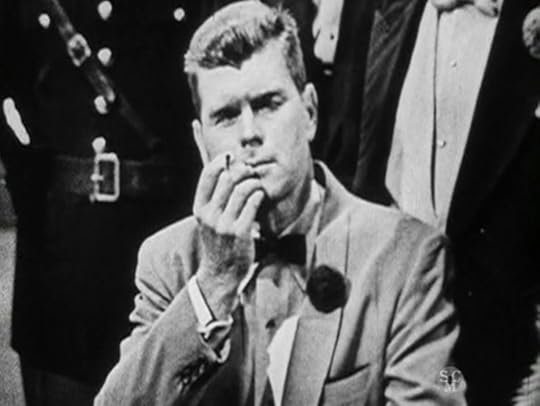

Climax!: "Casino Royale" (1954)

Ian Fleming always intended for Bond to get out of the books and onto the screen. In fact, the US edition of Casino Royale had only been out several months when it was adapted for TV by the hour-long, suspense anthology series, Climax . “Casino Royale” was the show’s third episode following an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye and the Bayard Veiller play The Thirteenth Chair(which had already been made into three different movies, one of which was directed by Tod Browning and co-starred Bela Lugosi).

The show was kind of a big deal. Though the few, remaining prints are black-and-white, the series was actually broadcast in color, which was rare in 1954. It was also hosted by film star William Lundigan (Dodge City, The Sea Hawk). But Fleming would come to regret the hastiness with which he accepted the Climax deal and it’s not hard to see why. The show famously changed James Bond into an American CIA agent named “Card Sense” Jimmy Bond, and while that was the most obvious and horrific alteration, it wasn’t the only one.

The Le Chiffre job is still an international operation coordinated by Britain, but Her Majesty’s Secret Service is represented by Clarence Leiter (replacing the novel’s American Felix), who says he works for Station S (the MI-6 branch in the novel that comes up with the mission). Clarence bankrolls Bond’s initial gambling stake and even debriefs him on the mission, a la M. Bond himself is clueless about the case when he arrives at the casino and at first assumes that he’s supposed to assassinate Le Chiffre.

Bond’s being briefed in the field by another agency isn’t so bad, but he comes across as fairly clueless through the whole episode. Barry Nelson (Shadow of the Thin Man, The Shining) plays him with a boyish quality that makes me believe he’s fun at a card table or on a date, but doesn’t create confidence in him as an agent. He has none of the cruelty of Fleming’s Bond and any meanness in his performance is a reaction to pain.

He’s a reactionary, helpless character all around. When it becomes clear that his life is in danger, he asks the casino to give him an armed guard. It’s Clarence who points out that winning the game might not be the end of the affair and suggests that Bond hide the winnings checque. (Also unlike the novel, there’s no mystery to where Bond hides the checque since the camera shows him doing it.) Bond doesn’t even get to chase Le Chiffre in order to rescue Vesper. The villain just shows up in Bond’s room with the woman to look for the checque and that’s where the final showdown and torture sequence (working on Bond’s toes with pliers instead of the much more effective technique used in the novel and the Daniel Craig movie) takes place.

Vesper is another major change. Her name is Valerie Mathis in the episode, suggesting that she’s combined with the Mathis character from the novel (though how much isn’t revealed until late in the story). When she’s introduced, it’s clear that she’s working with Le Chiffre, who’s using her because she has a previous relationship with Bond that may or may not have been true love depending on which of them you asked and how much you trusted their answer

In the novel, Le Chiffre uses disposable henchmen in addition to loyal Basil and the Corsican, but in the TV episode his entire operation is consolidated to three goons. Basil is still the main one, and the other two are given names and increased responsibilities. They all make various attempts to keep Bond out of Le Chiffre’s way and it’s them and Le Chiffre who directly bug Bond’s room and listen in on his conversations with Valerie.

Valerie appears to be an unwilling participant in Le Chiffre’s plans. He doesn’t trust her and she tells Bond that she’s only helping out of fear for his life. Not revealing Valerie’s motives right away is the episode’s way of handling the more complicated relationship with Bond and Vesper in the book, but by the end it’s clear that she’s not only on Bond’s side, but working for France’s Deuxième Bureau. In fact, she’s the source of extra funds that saves the mission (rather than Felix and the CIA from the novel).

But for all the changes the show makes to the novel, it works as its own thing. Clarence is a smart, charming agent; too affable to replace the absence of a real Bond, but still clever and likable. He and Jimmy Bond have great chemistry and I enjoy watching them work together.

I don’t know that I want to say that the episode makes improvements to the novel, but it does a couple of things differently that work better for the screen. TV Le Chiffre is more tenacious than novel Le Chiffre for instance. Fleming’s villain makes a couple of attempts to keep Bond from playing/winning the card game, but Climax has him constantly planning and scheming. The episode opens with an assassination attempt, then one of Le Chiffre’s henchmen tries to stick up Clarence before he can deliver the gambling stake to Bond. Just before the game Bond gets a phone call threatening Valerie’s life if he wins, there’s the cane-gun trick right out of the book (though it takes place after Bond’s already won and is really just another glorified stick-up), and of course Le Chiffre uses Valerie throughout to try to convince Bond to give up.

In the novel, Fleming reveals that Le Chiffre carries a few razors on him at all times as weapons, but they're just color and never come into play. The TV episode makes important use of one of them, which is pretty cool. And there are a couple of other cool nods to the book as well. Bond uses the same trick with music to overcome Le Chiffre’s bug, for instance, and one of the baccarat players is Lord Danvers who also sits in on the novel’s game. And speaking of the game, it’s a great nail-biter, made even more exciting by Bond’s having explained the rules to Clarence earlier.

The casting is good too. Linda Christian (Tarzan and the Mermaids) would make a lousy Vesper, but she’s a terrific Valerie. Her feelings for Bond look convincing, but she’s able to keep her true motives mysterious. When all is revealed, she comes across as intelligent and capable while also warm and caring. It’s sometimes tough to see anything but Peter Lorre in his characters, but I like his Le Chiffre. He’s cruel, but with a sense of humor. He’s not the Fleming character, but he’s still a capable, interesting villain all on his own.

The episode comes up with some memorable, original lines too. When Clarence meets Bond, he refers to the opening assassination attempt and asks if Bond was the fellow who was shot. “No,” Bond says, “I’m the fellow who was missed.” Later, Le Chiffre explains why he needs the checque. “My life depends on it,” he says; then menacingly, “So, incidentally, does yours.” Bond of course refuses and as Le Chiffre continues to insist, Bond finally tells him, “It took me long enough to win it. It’ll take you longer to get it back.” There are more than that, but those are my favorites.

There’s one more thing that I really like, though unintentional on the creators’ part. The Climax program opened with the credits playing as the viewer travels through a series of camera lenses, completely reminiscent of the famous gun barrel opening of the Bond films.

For purists, I imagine that’s just enough similarity to be frustrating, because otherwise this is Bond in name only. And certainly no one can blame Fleming for being upset with it or continuing to pursue other ways of bringing Bond to the screen. But Climax’s “Casino Royale” is more than just an historical curiosity. It’s a fast-paced, witty, thriller with some truly great moments, even if it’s not our Bond.

Published on February 17, 2014 04:00