The Monuments Men and the importance of art

My first reaction to The Monuments Men was how sad it is when art about the importance of art largely fails to communicate the importance of art. That’s what I tweeted right after I saw it, but I’d like to unpack that complaint a little more.

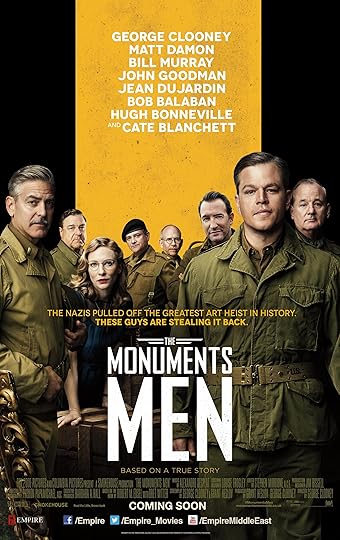

The Monuments Men spends a lot of time telling its viewers that art is important. George Clooney’s character assures the people around him (multiple times) that art is what the Allies are really defending against the Nazis. Art, he claims, is the memories of a civilization. An entire generation can be wiped out, but the culture will endure as long as its artifacts do.

His character arc is to discover just how much he thinks this is true. As his team lands in Europe he cautions them to be careful, saying that no piece of art is worth their lives. By the end of the film, he’s changed his mind about that. In a hammy scene, he debriefs FDR who pointedly asks if the mission was worth the loss of life. Clooney’s character proudly declares that yes it was. He’s clearly taken a journey in the film. The trouble is that I didn’t get to take it with him.The film doesn’t offer a compelling reason to care about the pieces that the team is trying to save. For all the talking about why art matters, the movie largely fails to show it in a way that makes an emotional impact. It tries a couple of times though, and it’s enlightening to take a look at those and see what they’re saying. Even if they don’t entirely succeed to support the stated message of the film, on their own they make some thoughtful points about the value of art.

There’s a moment that’s in the trailer when Matt Damon looks around at a room full of paintings and asks Cate Blanchett what all that stuff is. “People’s lives,” she says. In addition to the movie’s awesome cast, that’s the line that got me into the theater. Art is important to the extent that it reflects people’s lives. It’s why we sometimes call it culture. There’s a sense in which art documents the culture – the society; the thoughts and values – of the people who made it. That’s what the movie is trying to say, but for the most part it says it so academically that it’s tough to connect to that idea emotionally. Blanchett’s line helps correct that, but it’s not enough. And it’s undermined by other moments in the movie.

For instance, there’s another scene in which Matt Damon discovers the address where a painting came from and takes it back. Maybe it’s a famous painting, but I didn’t recognize it. More likely – and I actually, deeply hope this is the case – it’s just a portrait of a loved one. He takes it to the abandoned house from which the Nazis stole it and sees the discoloration on the wall where it once hung. As he puts it back, Blanchett comes into the room and says that the people who used to live there probably won’t be coming back. I forget Damon’s exact response, but he basically questions whether or not that matters. Which – in a nutshell – is the problem with the entire movie.

It’s a story about returning art to its proper place (though the definition of proper place is never debated and that could be a fascinating discussion all by itself). But The Monuments Men isn’t all that interested in why this is an important task. For Damon’s character, it’s just about the activity of returning art to the physical location from which it came. Blanchett suggests that it’s about returning it to the people for whom it has meaning. That can be a museum or other cultural center, but the appreciation of a museum patron for a piece is a crucially different thing than the meaning it holds for someone who’s intimately connected to it. The movie is interested enough in that difference to acknowledge it exists, but not enough to spend any time on it for the art that the team is actually tracking down and risking their lives for.

One final scene will help clarify what I’m talking about. It’s Christmastime and Bill Murray’s character gets a phonograph record from home. He doesn’t say what it is at first, just that he wants to hear it, and my first thought was that it was a new recording by a favorite musician. When he listens to it though, it’s revealed to be a recording of his family sending him greetings and then someone (His daughter maybe? The movie probably says, but I missed it.) sings “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

It’s a sweet moment and Murray reveals a lot of longing for home in that scene. But it’s made even more powerful by the juxtaposition of my expectation for the record and what it actually was. I thought it was just going to be a piece of art that he liked the way you like a painting in a museum or a carving in a church. Instead, it was art – specifically, a song – that he was deeply connected to because of the singer and the time of year. George Clooney could have made an entire movie about trying to rescue that record and I would have been more invested in it than I was in the salvation of the classically “important” pieces that are the focus of The Monuments Men.

It needn’t have been that way. Instead of just telling me that the Ghent Altarpiece is hugely important and needs to be saved, the film could have shown me how important it was to a character I cared about. It tries to do this with Michelangelo's Madonna of Bruges, but again, it tells me that this character likes that piece without ever convincing me why. And that's the overriding, fatal flaw of the rest of the film, too.

Published on February 19, 2014 04:00

No comments have been added yet.